Abstract

The incidence of cancer increases with age and demographics shows that the population of western countries is dramatically ageing. The new discipline of Geriatric Oncology is emerging aiming at providing tailored and patient-centred support to older adults with cancer. With the development of oral cancer therapy and outpatient treatments, Therapeutic Patient Education (TPE), aiming at enabling the patient and their relatives to cope with the disease in partnership with health professionals, appears to be an interesting and useful tool. The purpose of this paper is to search for evidence of the effectiveness of educational interventions for patients in older adults with cancer. The first screening found 2,617 articles, of which 150 were eligible for review. Among them, fourteen finally met the inclusion criteria: experimental and quasi-experimental studies enrolling older adults (over 65 years old), suffering from cancer and receiving an educational intervention. The types of educational intervention were diverse in these studies (support by phone and web base material). The results appear to be positive on anxiety, depression and psychological distress, patient knowledge and pain. However, data currently available on the effectiveness of a TPE program in Geriatric Oncology is lacking. Further studies are needed to assess the effectiveness of TPE programs adapted to the specific circumstances of the older adult.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Context

The prevalence of cancer in people over 65 years of age is high and increasing worldwide (1). Cancer is a public health issue in Western countries; by 2020 fifteen million new cases of cancer could appear per year, according to the World Cancer Report, compared to fourteen million in 2012 (1). The prevalence of cancer increases with age and the population is ageing. Theese two facts will cause the total number of older adults with cancer to increase dramatically in the future. For example, in France in 2015, 60,9 % of cancers diagnosed occurred in people over 65 years old and 10,9% occurred in people over 85 years of age (2, 3).

In addition, there are many age-related specificities in cancer management (comorbidities, treatment goals, drug toxicity, adherence to drugs, role of the relative…) underlying the necessity for Geriatric Oncology to develop.

Cancer has become a chronic disease thanks to advances in treatment. As patients suffer from a chronic condition, it appears that older adults with cancer could benefit from educational approaches and especially Therapeutic Patient Education (TPE). TPE is a basic, lasting component of patient management, according to the World Health Organization definition (WHO) (4). It aims at enabling people with chronic conditions to manage their illness and to cope with it in daily living, in partnership with health care professionals. TPE helps patients and their relatives acquire or maintain skills of self-management, through a patient-centred approach. By the mean of the specific methods and tools, tailored to the patient’s need, organised educational activities are planned by a multidisciplinary team: physicians, nurses, dieticians, pharmacists, physiotherapists, ergotherapists, psychiatrists/psychologists, social workers, occupational health specialists, chiropodists and other professionals (specialists in education, health insurance specialists, hospital

administrators, school health educators and others). The components of TPE are patient-centred

communication tools (active listening, empathy and motivational interview), pedagogical methods (participative learning, brainstorming, roundtable and role-play case studies) and educational tools (audio, video, web-based programs, e-learning, booklets etc.) (WHO). The format of any TPE program includes individual and/or group sessions designed to provide information on the disease but also to share experience and knowledge. TPE is finally a continuous process, integrated into health care designed to help patients and their families live with a chronic condition, adhere to treatment and to limit the complications and consequences of the illness on their quality of life.

TPE has shown efficacy in the treatment of chronic pathologies, such as asthma (5), diabetes (6), psychiatric diseases (7) (8), or obesity (9). Recently, this approach became an important component in the management of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers (10). In oncology it is a fast-growing tool, and its interest is all the more important with ambulatory care taking the lead, given the appearance of numerous oral treatment options (11).

TPE appears to us as a key element in the management of older adults patients with cancer; indeed, if studies have shown that TPE has a positive impact on adherence (12), quality of life and pain (13) in adults suffering from chronic illness, it has also been shown that older adults could benefit from it (14). Moreover, in the geriatric literature and clinical routine geriatrics, we know that an educational component is needed in any intervention designed to limit or avoid geriatric syndromes such as falls (15, 16), frailty (17), malnutrition (18) and loss of autonomy in general (19). Considering these two facts, it can be envisaged that preventing those geriatric syndromes2 could also be targeted outcomes for educational interventions in older adults with cancer. In the specific and heterogeneous population of older adults with cancer, the therapeutic educational sessions’s content must be tailored to, on the one hand, the disease (type of cancer), and on the other hand, the physiological or pathological age-related changes (mainly sensory and cognitive impairments) (20–22).

Review objective

We chose to realise a systematic review designed to search for evidence of the effectiveness of therapeutic patient education interventions in older adults with cancer on physical and mental health.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

Types of participants

This review considered studies that enrolled older patients, with an average age greater than 65 years old, of any gender and ethnicity, diagnosed with any form of cancer and receiving any treatments.

Types of interventions

This review considered studies in which the interventions included a therapeutic patient education aspect. Therapeutic patient education is rarely studied in itself in older adults with cancer, so we decided to consider any intervention with an educational component.

Comparator

We included studies in which the control group received information through usual care or usual education but not through a standardised multidisciplinary TPE method.

Types of outcomes

This review considered studies that included any outcome. We first envisage to study observance and quality of life, at the first step in our preliminary research, but finally chose to consider works studying any outcome.

Types of studies

This review considered experimental studies: randomised controlled trials. Other research designs such as quasi-experimental, before and after studies, prospective and retrospective studies, cohort studies, pilot studies and feasibility studies were also included.

Exclusion criteria

This review excluded studies concerning subjects under 65 years old and non-educative interventions. We excluded qualitative studies and those published before 1990.

Search Strategy

We analysed articles in English and French published between 1990 and July 2016. Several international databases were searched with identified keywords (Appendix 1): Medline, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and PsycINFO. A research of the grey literature was also conducted in Therapeutic Education and Geriatric Oncology journals.

One of the investigators is a Geriatrician. This research was conducted with the help of the primary care and family medicine department of the Toulouse University Hospital.

The second investigator is a Geriatrician too, who belongs to the Epidemiology and Public Health Department of the Faculty of Medicine of Toulouse. The research was conducted using identified keywords and index terms across all the included databases.

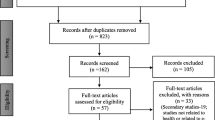

The first screening found 2,617 articles. After reading the title and the abstract, 150 were eligible to be reviewed. Among them, which we read through, fourteen finally met the inclusion criteria. The selection process is presented in the flow-chart (Figure 1).

The articles included in this review were assessed independently by the two investigators, who reviewed the abstracts, read and selected the full texts independently.

2.4 Method of the review

Methodology quality

We assessed the methodological quality of each study included with validated scales:

-

for randomised controlled trials: the CONSORT checklist (23) to analyse the quality of the report and Jadad score (24) to analyse the methodology of the study,

-

for non-randomised studies: the STROBE checklist (25) to analyse the quality of the report and Newcastle-Ottawa criteria (26) to analyse the methodology of the study.

Data extraction

Data from the studies were extracted by two independent investigators. The data extracted included the title, authors, country and year of publication, and details about the study scheme, population (age and type of cancer), interventions, study methods, primary and secondary endpoints and the main outcomes.

Data synthesis

Due to the clinical and methodological heterogeneity between the included studies, a meta-analysis was not possible.

Results

A total of fourteen articles were analysed in this literature review (Table 1). Among these fourteen articles, six were randomised controlled trials, three quasi-experimental studies, one prospective study, one cohort study, two pilot studies, and one feasibility study. They were conducted in several countries, with the majority in the United States (seven), Australia (two), Sweden (one), the Netherlands (two), Singapore (one) and Italy (one). They were published between 1993 and 2014.

There is great heterogeneity in the populations studied. Regarding our targeted population, it appears that older adults (over 65) were identified and specifically studied in only seven studies (33, 44, 47, 49, 50, 21, 52). In other studies, older participants were pooled with a general adult population. In one study, there was a comparison between a geriatric and a non-geriatric group (29).

The types of cancer studied are also diverse. The most prevalent were colorectal, prostate, breast and lung cancers, although there was also bladder, pancreatic, stomach, liver, kidney and small intestine cancers, lymphomas and myelodysplasias. Cancer stages varied according to the studies, as well as the treatments (chemotherapy and radiotherapy) received.

The interventions types were numerous. The vast majority of interventions were multi-dimensional and included an educational aspect, but were not exclusively educational or pedagogic.

The interventions’ follow up were also various. Patients were followed-up by phone (27, 32, 33, 50) or at home, through psychological support or via distribution of educational materials (33, 41, 44, 46, 47, 21, 52) in various forms (brochures, booklets, audio or video links to the Internet …). Educational interventions were mainly carried out through tools such as the telephone, video or the Internet. These interventions were not adapted to the specific learning capabilities of older adults except in one study (52).

Regarding the evaluation criteria, the most frequently assessed outcomes were anxiety, depression and psychological distress (27, 32, 33), as well as the patient’s knowledge and understanding (41, 44, 49, 52, 54) and their satisfaction (33) (50, 51). Many other criteira were represented: usefulness of intervention (46, 21), pain (47), the overall quality of life (29, 41), drug toxicity (50), patient compliance (41), quality of communication (44), quality of the monitoring (32) and physical health (51).

The more frequently found significant positive results were observed on pain, anxiety and quality of life (three for anxiety, two for pain and two for quality of life). One study showed an improvement of the patient’s depression (33) but another found no difference (27). Concerning the patient’s level of information (and recall of information) a majority of the studies were positive, only one found difficulty in remembering information for patients (49).

Thus, only one study (52) offered a suitably adapted program of therapeutic education (on the presentation of the educational material and the content of the information) to a geriatric population with an average age of 80 years of age. This study shows an increase in knowledge about cancer after this intervention. However, it deals with patients who do not have cancer but whose aim is preventive health care of older adults with respect to cancer. In addition, this was a pilot study with only 21 enrolled patients and an average methodological quality.

The methodological quality of the included studies have been assessed by the validated scales : the Jadad scale (24) or the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (26). The STROBE statement (25) or CONSORT checklist (23) have been used to estimate the quality of the study report. Tables 2 and 3 show summaries for each study, their detailed scores on the scales. In the randomised trials, blinding was impossible because of the type of interventions. Two of the randomised trials (27, 44) are of good methodological quality (Jadad score of 3).

Among the non-randomised trials (47, 51), two studies are of good methodological quality (Newcastle-Ottawa score > 75%).

Given the heterogeneity of the studies, we were not able to perform a meta-analysis.

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion

Only fourteen studies were included in this literature review studying educational interventions in older patients with cancer. The results of these studies are quite positive overall. Those interventions seem to provide positive effects on health outcomes but not only (knowledge and quality of life). However, none of these articles studied the effectiveness of a TPE specifically tailored for older patients with cancer (over 65 years of age). There is currently very little data in the literature on the effectiveness of Therapeutic Education in this population.

If data on patient education in geriatric oncology is poor, we realise that data was also lacking in adults under 65 years of age, through this literature review (56). Indeed, a systematic literature review performed in 2015 by a US team (56) found only two articles on the effectiveness of therapeutic education for adult patients regarding their compliance/observance with oral cancer treatment (average age 56 years (57) and 59.85 years old (58)) with cancer in an outpatient environment, between 1953 and 2014. These two studies had small-sized samples and their methodology was from weak to moderate. Therefore, the conclusion of this literature review is that further studies are needed to demonstrate that patient education can improve compliance with cancer treatments and their health outcomes. This is in accordance with our findings; data is limited in adult populations, but even more in older adults, virtually non-existent.

Our study raises this question: why Therapeutic Patient Education studies are so few in older populations despite the fact that TPE is recommended in chronic conditions and is expanding in Geriatrics and in Oncology? In a general manner, older patients with cancer are underrepresented in clinical trials. A 2012 article (59) showed that inclusion diminishes with age in these types of studies. The authors surmised that a decline in the functional reserve, increased comorbid conditions, concomitant medication use, lack of social/home support and decreased access among other factors contributed to poor enrolment among older adults. To remedy this situation, studies addressing older subjects need to take into account those specificities and need to be designed to gauge the weight of these specificities in this population. For example, there is a need to adapt interventions to the specific learning capabilities of older adults as mentioned by Barnes et al. (52). There is also a need to take into account the health care professionals; skills and needs in older adults with cancer management. On the one side, health care professionals feel their formation is lacking to address to accompany older subjects with cancer, which is a time-consuming activity for which one has to be committed. On the other side, they feel as though they are already giving out enough information, but it is not equivalent to using specific tools and pedagogical methods of education (60).

Thus, TPE, included in an integrated care management strategy, could provide benefits in terms of mental and physical health for the patient, their relatives but also in terms of health care system utilisation (avoid inappropriate admission, iatrogenia). It could increase the patient’s observance to the treatment, increasing the latter’s health outcomes, as it has been proven in other chronic diseases such as diabetes (6) or asthma (5). It could also decrease, and that is a major topic in Geriatric Oncology, the toxicity of chemotherapy by decreasing overuse and even reduce the misuse of care resources, in particular, hospitalisation.

Finally, the increase in the patient’s knowledge would allow them to be more involved in their care and enhance their role in the decision-making process.

Strengths

The main strength of this study is the innovative character of the approach since it is the first literature review on this topic in this population. In fact, this is a current topic, with the gradual increase in cancer prevalence in the patient population over 65 years of age.

Limitations

A major limitation of this study is the heterogeneity of the studies included, particularly because of their different study designs; their interventions are not fully comparable and their methodological quality is variable. The differences between the populations, health systems, the type of intervention, outcomes and methodological quality compound this heterogeneity. The fourteen studies included mostly had a small patient sample, which limits their ability to show a significant difference and makes it difficult to extract generalisations.

These heterogeneous results are due to the lack of scientific data on the efficacy of therapeutic patient education in older adults. We had to open the field of research to include any type of educational intervention in this population to show that it might indeed be a feasible and useful proposition. We feel that TPE including caregivers could improve parameters such as quality of life, compliance and pain management, amongst others. Our key finding is that data is missing regarding this subject in the scientific literature.

Geriatric oncology is developing, as well as the use of TPE as part of the care plan for these patients. Tailored TPE programs for older patients with cancer are implemented. Studies on this topic are becoming more numerous since six out of the fourteen selected articles were published after 2010.

There are several perspectives on TPE in geriatric oncology. We can surmise that, in the future, programs will be partly carried out by information and communication technologies. Indeed, we could imagine that, with the development of telemedicine, part of the educational approach could be carried out remotely in the form of online courses or discussion forum online with health care providers, for example.

Conclusion

There is a lack of data on TPE in the field of geriatric oncology. The effectiveness of a therapeutic education program for older adult cancer patients must be studied because of the efficacy of TPE in chronic conditions, the prevalence of cancer in older adults and the global ageing of the population. TPE could increase treatment compliance/observance, decrease side effects, improve health outcomes and have a positive effect on the quality of life of these patients and their relatives. Further studies, and especially studies of high methodological quality and level of evidence, are needed to assess the effectiveness of TPE in older adults with cancer.

References

Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Vol. X. Disponible sur: http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/epi/sp164/

Épidémiologie des cancers chez les patients de 65 ans et plus — Oncogériatrie | Institut National Du Cancer. Disponible sur: http://www.e-cancer.fr/Professionnels-de-sante/L-organisation-de-l-offre-de-soins/Oncogeriatrie/Epidemiologie

Institut national du cancer. Les cancers en France — Edition 2014. Disponible sur: http://www.unicancer.fr/sites/default/files/Les%20cancers%20en%20France%20-%20Edition%202014%20-%20V5.pdf

Therapeutic patient education: continuing education programmes for health care providers in the field of prevention of chronic diseases: report of a WHO working group. Disponible sur: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/108151

Horn IB, Mitchell SJ, Gillespie CW, Burke KM, Godoy L, Teach SJ. Randomized trial of a health communication intervention for parents of children with asthma. J Asthma Off J Assoc Care Asthma. nov 2014;51(9):989 95.

Golay A, Lagger G, Chambouleyron M, Carrard I, Lasserre-Moutet A. Therapeutic education of diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. avr 2008;24(3):192 6.

Pitschel-Walz G, Bäuml J, Bender W, Engel RR, Wagner M, Kissling W. Psychoeducation and compliance in the treatment of schizophrenia: results of the Munich Psychosis Information Project Study. J Clin Psychiatry. mars 2006;67(3):443 52.

Shimodera S, Furukawa TA, Mino Y, Shimazu K, Nishida A, Inoue S. Cost-effectiveness of family psychoeducation to prevent relapse in major depression: results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 14 mai 2012;12:40.

Snethen JA, Broome ME, Cashin SE. Effective weight loss for overweight children: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. J Pediatr Nurs. févr 2006;21(1):45 56.

Éducation thérapeutique dans la maladie d’Alzheimer. Disponible sur: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12612-014-0430-6

UNICANCER — Quelle prise en charge des cancers en 2020 ? Disponible sur: http://www.unicancer.fr/patients/quelle-prise-charge-cancers-2020

Foulon V, Schöffski P, Wolter P. Patient adherence to oral anticancer drugs: an emerging issue in modern oncology. Acta Clin Belg. avr 2011;66(2):85 96.

Ferrell BR, Rivera LM. Cancer pain education for patients. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1 févr 1997;13(1):42 8.

Pariel S, Boissières A, Delamare D, Belmin J. [Patient education in geriatrics: which specificities?]. Presse Medicale Paris Fr 1983. févr 2013;42(2):217 23.

Moylan KC, Binder EF. Falls in older adults: risk assessment, management and prevention. Am J Med. juin 2007;120(6):493.e1–6.

Clemson L, Cumming RG, Kendig H, Swann M, Heard R, Taylor K. The effectiveness of a community-based program for reducing the incidence of falls in the elderly: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. sept 2004;52(9):1487 94.

Leveille SG, Wagner EH, Davis C, Grothaus L, Wallace J, LoGerfo M, et al. Preventing disability and managing chronic illness in frail older adults: a randomized trial of a community-based partnership with primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. oct 1998;46(10):1191 8.

Bandayrel K, Wong S. Systematic literature review of randomized control trials assessing the effectiveness of nutrition interventions in community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. août 2011;43(4):251 62.

Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, Peduzzi PN, Allore H, Byers A. A program to prevent functional decline in physically frail, elderly persons who live at home. N Engl J Med. 3 oct 2002;347(14):1068 74.

Weinrich SP, Boyd M, Nussbaum J. Continuing education—adapting strategies to teach the elderly. J Gerontol Nurs. nov 1989;15(11):17 21.

Rigdon AS. Development of patient education for older adults receiving chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. août 2010;14(4):433 41.

Alywahby NF. Principles of teaching for individual learning of older adults. Rehabil Nurs Off J Assoc Rehabil Nurses. dec 1989;14(6):330 3.

The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Disponible sur: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673600043373

Assessing the Quality of Randomized Trials — Controlled Clinical Trials. Disponible sur: https://www.contemporaryclinicaltrials.com/article/S0197-2456(99)00026-4/abstract

Elm E von, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. PLOS Med. 16 oct 2007;4(10):e296.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. sept 2010;25(9):603 5.

Livingston PM, White VM, Hayman J, Maunsell E, Dunn SM, Hill D. The psychological impact of a specialist referral and telephone intervention on male cancer patients: a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. juin 2010;19(6):617 25.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. juin 1983;67(6):361 70.

Lapid MI, Rummans TA, Brown PD, Frost MH, Johnson ME, Huschka MM, et al. Improving the quality of life of geriatric cancer patients with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Palliat Support Care. juin 2007;5(2):107 14.

Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J, Chesterman E, Levi J, Shepherd R, et al. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis. 1981;34(12):585 97.

Cella DF. Quality of life outcomes: measurement and validation. Oncol Williston Park N. nov 1996;10(11 Suppl):233 46.

Johansson B, Berglund G, Glimelius B, Holmberg L, Sjödén PO. Intensified primary cancer care: a randomized study of home care nurse contacts. J Adv Nurs. nov 1999;30(5):1137 46.

Kornblith AB, Dowell JM, Herndon JE, Engelman BJ, Bauer-Wu S, Small EJ, et al. Telephone monitoring of distress in patients aged 65 years or older with advanced stage cancer: a cancer and leukemia group B study. Cancer. 1 déc 2006;107(11):2706 14.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 3 mars 1993;85(5):365 76.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983 1982;17(1):37 49.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1982. 1991;32(6):705 14.

Siegel K, Raveis VH, Mor V, Houts P. The relationship of spousal caregiver burden to patient disease and treatment-related conditions. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. juill 1991;2(7):511 6.

Amster LE, Krauss HH. The relationship between life crises and mental deterioration in old age. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1974;5(1):51 5.

George LK, Fillenbaum GG. OARS methodology. A decade of experience in geriatric assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. sept 1985;33(9):607 15.

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. juin 1983;140(6):734 9.

Ferrell BR, Rhiner M, Ferrell BA. Development and implementation of a pain education program. Cancer. 1 déc 1993;72(11 Suppl):3426 32.

Dodd MJ. Measuring informational intervention for chemotherapy knowledge and self-care behavior. Res Nurs Health. mars 1984;7(1):43 50.

McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Profiles of mood states. San Diego Educ Ind Test Serv. 1971

van Weert JCM, Jansen J, Spreeuwenberg PMM, van Dulmen S, Bensing JM. Effects of communication skills training and a Question Prompt Sheet to improve communication with older cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. oct 2011;80(1):145 59.

Old or frail: what tells us more? Disponible sur: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15472162

Jazieh AR, Brown D. Development of a patient information packet for veterans with cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 1999;14(2):96 8.

Clotfelter CE. The effect of an educational intervention on decreasing pain intensity in elderly people with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. févr 1999;26(1):27 33.

Grossman SA, Sheidler VR, McGuire DB, Geer C, Santor D, Piantadosi S. A comparison of the Hopkins Pain Rating Instrument with standard visual analogue and verbal descriptor scales in patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. mai 1992;7(4):196 203.

Jansen J, van Weert J, van der Meulen N, van Dülmen S, Heeren T, Bensing J. Recall in older cancer patients: measuring memory for medical information. The Gerontologist. avr 2008;48(2):149 57.

Yeoh TT, Si P, Chew L. The impact of medication therapy management in older oncology patients. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. mai 2013;21(5):1287 93.

Beydoun N, Bucci JA, Chin YS, Spry N, Newton R, Galvão DA. Prospective study of exercise intervention in prostate cancer patients on androgen deprivation therapy. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2014;58(3):369 76.

Barnes S, Thomas A. A modified cancer education program. Effect on cancer knowledge and beliefs of the elderly. Cancer Nurs. févr 1990;13(1):48 55.

Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175 83.

Cirillo M, Lunardi G, Coati F, Ciccarelli L, Alestra S, Mariotto M, et al. Management of oral anticancer drugs: feasibility and patient approval of a specific monitoring program. Tumori. juin 2014;100(3):243 8.

Cirillo M, Venturini M, Ciccarelli L, Coati F, Bortolami O, Verlato G. Clinician versus nurse symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute—Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events during chemotherapy: results of a comparison based on patient’s self-reported questionnaire. Ann Oncol. 1 déc 2009;20(12):1929 35.

Arthurs G, Simpson J, Brown A, Kyaw O, Shyrier S, Concert CM. The effectiveness of therapeutic patient education on adherence to oral anti-cancer medicines in adult cancer patients in ambulatory care settings: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 12 juin 2015;13(5):244 92.

Schneider SM, Adams DB, Gosselin T. A tailored nurse coaching intervention for oral chemotherapy adherence. J Adv Pract Oncol. mai 2014;5(3):163 72.

Simons S, Ringsdorf S, Braun M, Mey UJ, Schwindt PF, Ko YD, et al. Enhancing adherence to capecitabine chemotherapy by means of multidisciplinary pharmaceutical care. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. juill 2011;19(7):1009 18.

Scher KS, Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 10 juin 2012;30(17):2036 8.

Engel S, Reiter-Jäschke A, Hofner B. [“EduKation demenz®”. Psychoeducative training program for relatives of people with dementia]. Z Gerontol Geriatr. avr 2016;49(3):187 95.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Mrs Maryline Pasotti for participation in the english translation.

Funding

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Champarnaud, M., Villars, H., Girard, P. et al. Effectiveness of Therapeutic Patient Education Interventions for Older Adults with Cancer: A Systematic Review. J Nutr Health Aging 24, 772–782 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1395-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1395-3