Abstract

There is growing recognition that global food system transformation requires a fundamental shift in norms, perspectives and structural inclusion and exclusion of different actors in decision-making spaces. As multistakeholder governance approaches become increasingly common, significant concerns have been raised about their ability to deliver such change. Such concerns are based on case study findings repeatedly highlighting their susceptibility to corporate capture. This study goes beyond individual case studies, examining global multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) whose stated aim is to drive a healthier and more sustainable food system. It identified and categorised actors within these MSIs, drawing on social network analysis to provide insights into actor centrality, power structures, and how this might impact MSIs’ potential to drive transformative change. Thirty global MSIs were included in our sample, including a total of 813 actors. Most actors were based in high-income countries (HIC) (n = 548, 67%). The private sector (n = 365, 45%) was the most represented actor category, comprising transnational corporations (TNCs) (n = 127) and numerous others representing their interests. NGOs, affected communities and low- and middle-income country actors remain underrepresented. The central involvement of TNCs which rely on the production and sale of unhealthy and unsustainable commodities represents a clear conflict of interest to the stated objectives of the MSIs. These findings lend weight to concerns that MSIs may reflect rather than challenge existing power structures, thus serving to maintain the status quo. This indicates a need to critically examine the use of multistakeholder governance approaches and their ability to drive global food system transformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The interlinked challenges of undernutrition, obesity and climate change present a significant global concern for human and environmental health (Swinburn et al., 2019). ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022’ report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) recently concluded that the world is “moving backwards in its efforts to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms” (FAO, 2022, p. 129). Increasingly, these challenges are seen to be exacerbated by a highly unsustainable food system, which includes activities across the commodity chain (including farming, processing, retailing, marketing and consuming), their associated actors, the socio-economic and environmental drivers and constraints that influence the actors’ behaviour, and the outcomes of these activities on different nutritional, socioeconomic and environmental goals (Ingram & Thornton, 2022). It is now well established that food system challenges will not be addressed through simple technical ‘fixes’ but rather require more holistic, systems-based approaches to ‘transform’ the food system to be more affordable, sustainable, health-promoting and inclusive (Candel & Pereira, 2017; IFPRI, 2021; Van Bers et al., 2019).

Global food system governance increasingly relies on multistakeholder approaches which are promoted as being more inclusive, result in more diverse policy outputs and are therefore better able to respond to the complexity of the global food system than traditional governance methods could (Ansell & Gash, 2007; Siddiki et al., 2015). Multistakeholder approaches are defined by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) (2018) as “any collaborative arrangement between stakeholders from two or more different spheres of society (public sector, private sector and/or civil society), pooling their resources together, sharing risks and responsibilities in order to solve a common issue, to handle a conflict, to elaborate a shared vision, to realize a common objective, to manage a common resource and/or to ensure the protection, production or delivery of an outcome of collective, and/or, public interest” (HLPE, 2018). The emphasis on having a common vision or objective is both one of the core rationales behind engaging in multistakeholder initiatives (MSIs) (Dentoni et al., 2018) and a cause for concern for many who point out the different issue framings, objectives and interests in the food system, particularly when including commercial actors whose profit is derived from unsustainable products and practices (Carriedo et al., 2022; Lauber et al., 2020; McKeon, 2017).

As multistakeholder approaches increasingly invite non-state actors into decision-making spaces at national and, as is the scope of this paper, global level, it is increasingly relevant to understand how power relations, perspectives and solutions are reflected in, enabled through or challenged by multistakeholder governance approaches and what this might mean for their potential to drive food system transformation (Conti et al., 2021; Leeuwis et al., 2021). Given the normative connotations of global food system transformation as oriented towards creating a ‘better’ system, rather than merely addressing certain specific problems, these differences in perspectives of what ‘better’ looks like can determine the direction, extent and pace of change (Béné, 2022; Montenegro De Wit et al., 2021). Systemic change and innovation are fundamentally driven or limited by a complex system of actors, organisations and institutions who may have different and, at times, conflicting problem conceptualisations and framings, subsequently leading to different solutions (Ingram & Thornton, 2022; Mesiranta et al., 2022; Suzuki et al., 2021). Consequently, concentration of power within a small group of actors will limit the types of approaches that are seen as feasible or desirable, thereby limiting the potential for truly transformative change to emerge (Clapp, 2021; Montenegro De Wit et al., 2021).

One of the key criticisms levelled against MSIs is that they may be susceptible to capture by commercial actors and that this might jeopardise their ability to drive systemic change (Chandrasekaran et al., 2021; McKeon, 2017). Indeed, one of the most high-profile global multistakeholder platforms, the 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) faced significant criticism over its central inclusion of transnational corporations, failure to acknowledge power asymmetries and exclusion of indigenous and civil society groups (Canfield et al., 2021; Clapp et al., 2021). Partly as a consequence of including certain actors over others, the solutions proposed through the UNFSS were predominantly focused on technological innovation, maintaining a perspective of the food system rooted in extractivist and capitalist interpretations that fail to meet the needs of most people in the food system (Fakhri, 2022; Montenegro De Wit et al., 2021). Both this process and these outcomes fail to reflect the wide variety of perspectives and actors in the global food system (Montenegro De Wit et al., 2021), leading many to reject the UNFSS and voice concerns that such multistakeholder processes contribute to maintaining the status quo and further embed corporate power in the global food system (Chandrasekaran et al., 2021; CSIPM, 2021).

And yet, aside from research on the networks of actors involved in the UNFSS (Chandrasekaran et al., 2021), there remains a lack of research taking a network approach to MSIs. Most existing research on the actors and power relations that make up MSIs use case study approaches to analyse individual MSIs. Seeking to address this gap, this paper sought to draw on a comprehensive set of global MSIs to: examine the nature and power of actors involved in global MSIs; to map the network of these actors and MSIs, using that to examine the power dynamics within the network; and draw lessons on the implications of multistakeholder approaches for global food system transformation.

2 Methods

2.1 Case selection

As there is no official registry of multi-stakeholder initiatives, we based our initial selection of MSIs on a recent review conducted by the World Wildlife Fund UK (WWF-UK) and SustainAbility – ‘Sustainable Food Systems and Diets: A Review of Multi-stakeholder Initiatives’ (Harvey, 2018). This report was published in 2018 and comprised a desk-based review supplemented by interviews with key stakeholders in the global food system (Harvey, 2018). For the current study we screened all initiatives in this review, excluding all those that did not have a global scope or were no longer active at the time of screening.

To supplement this and identify any relevant MSIs that have emerged since the review, we conducted a search of the academic and grey literature in March 2023. First, we searched three academic databases: International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), SCOPUS and GreenFILE, which together were considered to cover all topic areas that MSIs relevant for this study would fall under. The WWF review did not include a comprehensive overview of the search strategy and inclusion criteria used. To ensure our sample covered the same types of initiatives covered in the WWF report, we adapted the terms used in the WWF report, namely: (multi-stakeholder OR 'multi AND stakeholder') AND (initiative OR partnership OR collaboration OR platform) AND global AND 'food AND system'. We screened any results, using a narrative review informed by the WWF document, to identify names of potentially relevant MSIs in these articles. For our search of the grey literature, we conducted a Google search using the same search terms. The first ten pages of Google results, consisting of 100 results, were screened for relevant MSIs. As Google automatically organises its search results according to relevance, this was considered to be a sufficiently extensive search boundary.(Godin et al., 2015) For both searches, we only included English-language records and did not have any restrictions on the time period.

2.2 Data extraction and analysis

For each of the included MSIs, we extracted the names of founders, funders and partners that were publicly available on their websites and in their strategic or yearly reports. If founders, funders or partners were not available on the website of the MSI or we were unable to identify the specific partner, for example if they were referred to only as ‘UN agencies’ or ‘the private sector’, we did not include the partner in our analysis. When an MSI was clearly hosted by a different organisation (for example when identified in a project page on the host organisations’ website), we also extracted information on the partners of this ‘host organisation’. Data were extracted into Excel by the lead author. We categorised actors building on Baker & Demaio’s, 2019 Food Systems Actor Framework, which distinguishes between market, state, civil society and hybrid actors (Baker & Demaio, 2019). We added some relevant categories, including research institutes and universities, and have further divided the private sector category into more specific subcategories, given the heterogeneity of this category and its relevance to the current study (Table 1). Actors were categorised according to how they describe themselves on their website or how they are described on the website of the MSI of which they were a partner. For non-governmental organisations (NGOs), we screened their websites for their funders and board members to identify whether these included private sector actors. We then counted the actors within each of the categories and identified where they were located to gain an indication of the global spread of the actors in the network.

While we make a distinction in our categorisation between industry-funded research institutes and other academic institutions, this is not complete and should not be taken to mean that all academic institutions that are not within the ‘industry-funded non-profit or research institute’ category have no industry funding. It was not feasible, within the resource constraints of this research, to comprehensively investigate all funding sources of universities and research institutions. Hence, the ‘industry-funded non-profit or research institute’ category covers only those research institutes whose industry-funded status is particularly clear, such as the Nutricia Research Foundation example given in the table, which was founded by N.V. Verenigde Bedrijven Nutricia, currently Danone.

Using Kumu software (Kumu, 2023), we translated the data into a network map that shows the different actor categories and relationship between actors. Actors are represented as nodes, with their colour indicating their category (e.g. private sector, government) and their size indicating the number of direct connections to MSIs. For visual clarity, we combined actors sharing the same category, in instances where five or more actors in this category linked only to one particular MSI, so as not to crowd the map. These instances are represented by squares and are scaled according to the number of organisations within this category. All other nodes are scaled according to the number of links they have. The structure of the map was determined through force direction so that the different actors were automatically placed in the map according to their connections to other actors, with minimal rearrangement. This meant that actors with more connections would automatically be placed closer to the centre of the map, while those with fewer connections would be placed more to the outside of the map. The only adjustments made by the researchers were to move apart overlapping nodes so that their names are visible.

We drew on Social Network Analysis (SNA) methods to analyse the networks of actors included in the MSIs and identify the structure created by the relationships between these actors across MSIs (Freeman, 2004; Wasserman & Faust, 1994). In doing so we approach this network with a recognition of the interconnectedness of actors across a network and the influence that actors’ centrality in this network has on their ability to shape and drive the network (Hermans et al., 2017). We used the built-in SNA analysis tool in Kumu (Kumu, 2023) to calculate degree centrality, which measures the number of direct connections that actors have within a network (Golbeck, 2013; Njotto, 2018). Following prior research using SNA in the context of multistakeholder platforms (Hermans et al., 2017), we take the degree centrality of actors as a measure of their structural power in this network.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of included MSIs

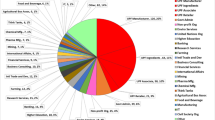

Of the 93 multi-stakeholder initiatives included in the WWF report, 31 were global in scope and thus relevant to this study (Harvey, 2018). Of these, nine MSIs were no longer active at the time of data collection, leaving 22 relevant and active MSIs. Our updated search identified eight more MSIs resulting in a total of 30 relevant global MSIs being included in our analysis (Annex 1). These 30 MSIs together listed 813 partners on their websites (Annex 2). Some MSIs ((Food Coalition, 2023), GROW (Oxfam International, 2023)) report only one partner, while others report as many as 344 partners (Alliance of Biodiversity & CIAT, 2023). The publicly available data were not always sufficiently specific to indicate the types of information flows between actors and between actors and the MSI. Connections may therefore indicate either or both financial and non-financial contributions to the MSI. The most represented actor categories were private sector actors (n = 365), which included transnational corporations (n = 127) business associations (n = 69), consulting firms (n = 62), industry-funded not-for-profit organisations (n = 8), private foundations (n = 37) and other private sector actors (n = 62) (see Fig. 2). This was followed by academic institutions (n = 217), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (n = 81), governments (n = 82) and international organisation (IO) (n = 35). Figure 1 shows the categories of actors and Fig. 2 shows the subcategories within the private sector category, both divided by which World Bank country income category they are located in. Not pictured in Table 1 and Fig. 1 as a separate category were two journals that present in the network: the Lancet and the Economist.

Private sector actors involved in MSIs, by private sector actor subcategory (Table 1) and World Bank country income category

Aside from the private sector category in Fig. 1, private sector actors also exert influence through third parties in other categories. As mentioned in Section 2.2, some academic institutions may take industry funding, which we were not able to comprehensively determine for many universities and large research institutions, and which is therefore not captured in this categorisation. For example, the University of Oxford, while categorised as an academic institution, is present in the current network because they convene the FoodSIVI MSI with funding from Nestle, Yara and Syngenta. Similarly, the International Livestock Research Institute is partly funded by the Syngenta Foundation and Sir Ratan Tata Trust Fund, founded by the Chairman of Tata Steel. Similarly, while Fig. 2 has a specific subcategory for transnational corporations, many actors who are in one of the other private sector subcategories, such as business associations or industry-funded non-profits, represent TNCs’ interests.

3.2 Network analysis

Figure 3 shows the overall network map of MSIs and their direct partners and funders. MSIs are represented by red and white hexagonal nodes, while actors are represented by circles. Where five or more actors in the same category linked only to one MSI, these are grouped together and represented by a square, scaled according to the number of actors within this category, so as to not crowd the network map.

The network shows that, while different actor categories had distinct clusters in which they were concentrated, transnational food and agricultural corporations were among the most represented and central actors in the network. All but two (Diageo plc and Kweichow Moutai Co. Ltd.) of the ten largest food and beverage companies in the world in 2022 according to Forbes (Sorvino, 2022), were a partner, funder or founder of at least one MSI. While non-governmental organisations (NGOs), research institutes and universities were more evenly spread throughout the network, they were overall less represented, with the exception of two international NGOs (WWF and EAT), and a number of research institutes and universities (notably Wageningen University, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and CGIAR (formerly the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research)).

Crucially, the influence of TNCs in the current network is likely to be underestimated, as ties between TNCs and MSIs may occur not through direct involvement but through business associations, industry-funded NGOs and research institutions and other third parties. For example, the Sustainable Food Lab, a ‘non-profit organization to create a sustainable food system’(Sustainable Food Lab, 2023) has ties to three MSIs included in this map and has mainly large transnational corporations as its members while having high-level executives from ABInBev, MARS, PepsiCo and Syngenta, among others, in its Leadership Circle, to “help promote and set the Food Lab’s focus” (Sustainable Food Lab, 2023). The World Business Council on Sustainable Development (WBCSD), the host organisation of one of the MSIs, is one of the most central actors in the network and counts among its members many transnational food corporations as well as some of the largest oil, tobacco and alcohol companies (including ABInBev, BP, Philip Morris International and Shell) (World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2023). While links to NGOs, research institutes, universities and governments were often directly mentioned on the MSI’s website, links to transnational corporations that occurred through a host organisation or front group were not visible on the MSI’s website itself.

3.3 Most central actors

The network map includes a highly concentrated network, with many of the most central actors sharing membership of multiple MSIs. Of the 806 included actors, 120 were part of more than one MSI and 11 actors were part of 5 or more MSIs (see Table 2). The actor with the most direct connections – to 12 MSIs – was the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, followed by the WBCSD (9 MSIs), Nestlé and the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) (8 MSIs) and the government of the Netherlands, WWF, Bayer, Unilever, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), the European Commission and EAT (6 MSIs). Of these 11 most central actors, five (45%) are transnational corporations or have transnational corporations among their core funders and/or members (labelled in Table 2 with an *).

4 Discussion

This study sought to map the network of actors involved in a subset of MSIs, provide insights into their nature and power and draw lessons on the implications of multistakeholder approaches for global food system transformation. It is one of the first studies to go beyond the case study approach and assess these actor networks and power relations across multiple MSIs in the global food system. Our findings show that within a highly concentrated network, private sector actors are by far the most heavily represented and most central, i.e. most networked, actors across MSIs. Moreover, high-income country governments, most notably those that are host to food and agricultural TNCs, and the European Commission are three times more represented than low-income countries who bear the brunt of the impacts from the current unsustainable food system. Similarly, public sector NGOs and affected communities are structurally underrepresented throughout the network, with NGOs accounting for 10% of all 813 actors (n = 81), of which half (n = 41) are situated in HICs. NGOs from low and lower-middle income countries together make up only 4% of actors (n = 29), while organisations falling under the private sector category account for 45% (n = 365) of all actors. This figure accounts for the multiple ways in which TNC interests are represented – directly, through business associations, consulting firms, industry-funded non-profits and so on, highlighting that any analysis that just examines TNCs will underestimate their influence.

While our findings are supported by numerous case studies highlighting the role of power asymmetries and conflicts of interest in limiting their ability to drive transformative change (Eidt et al., 2020; Herens et al., 2022; Hofmann, 2016; Sethi & Schepers, 2014), this study is the first to highlight these power relations across MSIs. While multistakeholder approaches are presented as inclusive and participatory (Gray & Purdy, 2018; Kalibata, 2020), our findings indicate that MSIs predominantly include actors who already have economic and/or decision-making power and suggest that MSIs reflect rather than challenge an increasing concentration of corporate power in the global food system (Clapp, 2021). For example, while one of the MSIs describes itself as “a coalition of executives from governments, businesses, international organizations, research institutions, farmer groups, and civil society” (Champions12.3, 2023), the list of its current members consists mostly of CEOs of large corporations such as Nestlé, Unilever and Kellogg’s and officials from governments and International Organisations (Champions12.3, 2023).

Although we accounted for direct representation of TNC interests, as discussed above, this may underestimate TNC influence and power through indirect representation of TNC interests. Research continuously shows that academic institutions, which we have coded as independent, take funding from food and agricultural industries, which has been known to grant industry influence over their research agenda (Fabbri et al., 2018). Similarly, HIC governments that host TNCs have been known to align with food industry interests in global governance spaces, using industry-beneficial problem framing and keeping more systemic policy options, which would harm the food industry’s business interests, off the table (Barlow & Thow, 2021; Lauber et al., 2021). Numerous research highlights the problems associated with centralised power in transformative change, which are discussed below in the context of our findings.

While the central involvement of powerful actors is not necessarily detrimental to a network’s potential to drive innovation (Pel, 2016), case study research does suggest that powerful actors’ central presence in multistakeholder partnerships contributes to their being less likely to lead to transformative food system change (Berliner & Prakash, 2014; Herens et al., 2022; Osei-Amponsah et al., 2018). In part, this is because a concentrated, uniform network may be limited in its potential to incorporate new developments, insights or perspectives (Klein Woolthuis et al., 2005). The network mapped in this study, consisting for 45% of private sector actors, is particularly uniform. Our findings highlight that there is substantial disparity in access between different actors to this network, which for example includes 304 private sector actors from high-income countries while only including 9 public-sector NGOs from low-income countries, despite research emphasising the importance of including different perspectives, particularly those of affected communities and indigenous peoples, to shift understanding of an issue and enable transformative change (Leeuwis et al., 2021; Montenegro De Wit et al., 2021). As such, our findings support prior research at national level which found that disparities between stakeholder groups were often reflected in and exacerbated by disparities in access to multistakeholder platforms (Eidt et al., 2020).

In addition, a concentrated network is less likely to lead to transformative change when the network centrally includes powerful actors that benefit from the status quo as they are more likely to benefit from and be invested in the status quo, and may seek to stifle changes that threaten their power base (Burkhardt & Brass, 1990; Smith et al., 2014). In the context of the global food system, there are concerns that when included in multistakeholder decision-making processes, actors whose power – financial or otherwise – is contingent on the current status quo of the global food system will seek to maintain and defend this system, steering towards incremental rather than transformative change (Chandrasekaran et al., 2021; De Schutter, 2017). Our findings lend weight to existing concerns over conflicts of interest in MSIs (Fanzo et al., 2021; McKeon, 2017; Turner et al., 2020) by showing that some of the most central actors in this network of MSIs are transnational corporations who profit from the production and sale of unhealthy and unsustainable products and whose interests therefore conflict with the (claimed) goal of these MSIs – to drive a healthier and more sustainable food system. For example, Nestlé, the third most central actor in the current network, relies on the sale of some products that leaked documents show the company admits “will never be ‘healthy’ no matter how much we reformulate” (Evans, 2021).

When considering power relations in the context of a centralised network as the one in this study, there is a risk of oversimplifying the role of powerful, particularly commercial, actors as a homogeneous group resisting transformation, which may not accurately reflect the plurality of these actors’ interests (Turnheim & Sovacool, 2020). Crucially, it is not just the actors and their roles, but rather the network of actors across multistakeholder institutions, and the structural power this reflects and embeds, that this study highlights as a potential barrier to transformative change. While the resources of the private sector can be powerful levers for change, their central inclusion across governance spaces, as indicated in this study, raises concerns about power concentration in the network of MSIs, leading to questions about whether MSIs and the power structures at their centre represent the novel configuration of actors, institutions and norms that system transformation requires (Obstfeld, 2005; Weber & Rohracher, 2012).

Commercial actor involvement in multistakeholder processes has been argued to not only further entrench power asymmetries within MSIs but also to normalise their involvement in governance spaces more generally (Chandrasekaran et al., 2021; Clapp et al., 2021). Through normalising shared platforms between commercial actors and global decision-makers, it has been suggested that MSIs provide commercial actors with key access into global decision-making processes while bypassing usual routes of accountability (Chandrasekaran et al., 2021; IPES-Food, 2023). Indeed, the findings from this study show how commercial actors and decision-makers and UN institutions are deeply and consistently connected to each other through MSIs which provide a shared space for these actors to interact on a regular basis. For example, PepsiCo, Unilever, Nestlé and Mondelez are all linked to the FAO through multiple MSIs. Unilever, Kellogg’s and Nestlé also share membership of an MSI with UNEP, and Nestlé further shares an initiative with the UN System Standing Committee on Nutrition (UNSCN), which is, according to its website “a place where UN agencies can design joint global approaches, and align their positions and actions” [emphasis in original] (UNSCN, 2023).

One MSI included in the current study notes that building strong connections between the private sector, members of the alliance, and key UN and NGO communities allows the private sector to be more engaged in policy discourse and “the development of guiding frameworks to ensure relevance and impact for agribusiness” (World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2019). By providing and legitimising such platforms for continuous engagement, MSIs further embed a culture of collaboration that is antithetical to what research suggests is needed to drive systemic change in contexts where powerful commercial actors’ interests are in conflict with the public good (Gilmore et al., 2023; Lacy-Nichols & Williams, 2021; Lelieveldt, 2023). The extent of corporate influence in MSIs as highlighted in this study may therefore have an impact beyond the MSIs themselves, lending weight to concerns that MSIs further institutionalise corporate power in global food governance and so ultimately lead to solutions that maintain the status quo rather than enable the shifts in norms and power relations that food system transformation requires (Béné, 2022; Chandrasekaran et al., 2021).

4.1 Limitations

One limitation of this study is that there is no official registry of multistakeholder initiatives. We attempted to mitigate this by building our database of MSIs from a review of such initiatives conducted by the WWF, supplemented by an academic and grey literature review to identify additional MSIs. Nevertheless, the risk remains that we may have missed some initiatives either through our own search strategy or by basing our initial sample on the WWF review, which itself did not include clear selection criteria and may therefore have missed certain initiatives. Even if the MSIs included in this study make up only a subset of total MSIs, however, these are likely to be representative of MSIs in this area more generally. Indeed, research on a different subset of multistakeholder governance approaches in the global food system shows similar results in terms of the actor categories most represented in these, suggesting similar trends across multistakeholder approaches (Chandrasekaran et al., 2021; Slater et al., 2024). Membership of MSIs is likely not fixed but changes over time, meaning that the sample is necessarily only capturing a snapshot of what is in reality a dynamic network of partners. Nevertheless, the sample presents a reliable overview of the partnership relations across multiple MSIs, and as such is useful to understand the structural in- or exclusion of different actors across MSIs. A second limitation is that we relied on actors’ self-reported, publicly available, data. We might have missed some connections, as we did not include, for example, shared board membership between organisations, employment histories of board members or initial funders of organisations when these were not listed on the relevant website. Additionally, the available data were often inconsistent in detail and generally insufficient to accurately determine the exact pathways of influence and strength of relationship between different actors. For example, it was at times impossible to determine the difference in decision-making power granted to ‘strategic’ partners as opposed to other partners. While this limited the detail we were able to include in the SNA, the degree centrality of different actors in the overall network still provided an important indicator of structural power and network concentration.

4.2 Future research

This research raises a number of issues which warrant further investigation. One of these is the transformative potential of the recommendations for actions proposed by these MSIs when compared to those by other actors, notably those independent of the private sector, at both global and national level, accompanied by an analysis of their implementation and effectiveness. Moving beyond individual MSIs, however, it is important to reflect on the wider governance context that increasingly includes corporate actors in global governance structures. There is a need for more critical engagement with this structural inclusion of powerful actors through multistakeholder governance to understand how this impacts the integrity of global governance more generally.

5 Conclusion

To make the global food system healthier and more sustainable requires both large-scale change and a fundamental shift in perspectives, norms and power relations (Béné, 2022). Through mapping the network of actors involved in 30 global food system multistakeholder initiatives (MSIs), this study identifies a highly centralised network dominated by powerful commercial actors whose interests conflict with the stated purpose of the MSI, and largely HIC political actors – many of which host these transnational corporations. By contrast, affected communities and civil society organisations remain mostly on the networks’ fringes or excluded entirely. These findings suggest MSIs will be unable to drive the necessary transformative change to the status quo that these actors’ profits depend on and may further embed and normalise existing power structures in the global food system.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data analysed during this study are included in this published article and supplementary materials.

References

Alliance of Biodiversity & CIAT. (2023). Alliance of Biodiversity & CIAT. Retrieved from https://alliancebioversityciat.org/

Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

Baker, P., & Demaio, A. (2019). The political economy of healthy and sustainable food systems. In M. Lawrence & S. Friel (Eds), Healthy and Sustainable Food systems (pp. 181–192). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351189033

Barlow, P., & Thow, A. M. (2021). Neoliberal discourse, actor power, and the politics of nutrition policy: A qualitative analysis of informal challenges to nutrition labelling regulations at the World Trade Organization, 2007–2019. Social Science & Medicine, 273, 113761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113761

Béné, C. (2022). Why the Great Food Transformation may not happen – A deep-dive into our food systems’ political economy, controversies and politics of evidence. World Development, 154, 105881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105881

Berliner, D., & Prakash, A. (2014). “Bluewashing” the firm? Voluntary regulations, program design, and member compliance with the united nations global compact. Policy Studies Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12085

Burkhardt, M. E., & Brass, D. J. (1990). Changing patterns or patterns of Change: The effects of a change in technology on social network structure and power. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 104–127. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393552

Candel, J. J. L., & Pereira, L. (2017). Towards integrated food policy: Main challenges and steps ahead. Environmental Science & Policy, 73, 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.04.010

Canfield, M., Anderson, M. D., & McMichael, P. (2021). UN food systems summit 2021: Dismantling democracy and resetting corporate control of food systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5:661552. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.661552

Carriedo, A., Walls, H., & Brown, K. A. (2022). Acknowledge the elephant in the room: The role of power dynamics in transforming food systems comment on “What opportunities exist for making the food supply nutrition friendly? a policy space analysis in Mexico.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2022.7382

Champions 12.3. (2023). About champions 12.3. Retrieved from https://champions123.org/. Accessed on 23 Jul 2024

Chandrasekaran, K., Guttal, S., Kumar, M., Langner, L., & Manahan, M. A. (2021). Exposing corporate capture of the UNFSS through multistakeholderism. Retrieved from https://foodsystems4people.org/multistakeholderism-report/

Clapp, J. (2021). The problem with growing corporate concentration and power in the global food system. Nature Food, 2(6), 404–408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00297-7

Clapp, J., Noyes, I., & Grant, Z. (2021). The food systems summit’s failure to address corporate power. Development, 64(3), 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-021-00303-2

Conti, C., Zanello, G., & Hall, A. (2021). Why are agri-food systems resistant to new directions of change? A Systematic Review. Global Food Security, 31, 100576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100576

CSIPM. (2021). People who produce most of the world’s food continue to fight against agribusiness-led UN food summit. Retrieved from https://www.csm4cfs.org/people-who-produce-most-of-the-worlds-food-continue-to-fight-against-agribusiness-led-un-food-summit/

De Schutter, O. (2017). The political economy of food systems reform. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 44(4), 705–731. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbx009

Dentoni, D., Bitzer, V., & Schouten, G. (2018). Harnessing wicked problems in multi-stakeholder partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(2), 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3858-6

Eidt, C. M., Pant, L. P., & Hickey, G. M. (2020). Platform, participation, and power: How dominant and minority stakeholders shape agricultural innovation. Sustainability, 12(2), 461. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/2/461

Evans, J. (2021). Nestlé document says majority of its food portfolio is unhealthy. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/4c98d410-38b1-4be8-95b2-d029e054f492

Fabbri, A., Lai, A., Grundy, Q., & Bero, L. A. (2018). The Influence of industry sponsorship on the research agenda: a scoping review. American Journal of Public Health, 108(11), e9–e16. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2018.304677

Fakhri, M. (2022). The food system summit’s disconnection from people’s real needs. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 35, 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-022-09882-7

Fanzo, J., Shawar, Y. R., Shyam, T., Das, S., & Shiffman, J. (2021). Challenges to establish effective public-private partnerships to address malnutrition in all its forms. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.262

FAO. (2022). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Retrieved from Rome.

Food Coalition. (2023). Food Coalition. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/food-coalition/en

Freeman, L. (2004). The development of social network analysis. Empirical Press.

Gilmore, A. B., Fabbri, A., Baum, F., Bertscher, A., Bondy, K., Chang, H.-J., ... Thow, A. M. (2023). Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. The Lancet, 401(10383), 1194–1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00013-2

Godin, K., Stapleton, J., Kirkpatrick, S. I., Hanning, R. M., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2015). Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Systematic Reviews, 4, 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0

Golbeck, J. (2013). Analyzing the social web (1st ed.). Amsterdam.

Gray, B., & Purdy, J. (2018). Collaborating for our future: Multistakeholder partnerships for solving complex problems. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198782841.001.0001

Harvey, M. T., J. (2018). Sustainable Food Systems and Diets: A Review of Multi-stakeholder Initiatives. Retrieved from https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-10/59078%20Sustainable%20food%20systems%20report%20-%20ONLINE.pdf

Herens, M. C., Pittore, K. H., & Oosterveer, P. J. M. (2022). Transforming food systems: Multi-stakeholder platforms driven by consumer concerns and public demands. Global Food Security, 32, 100592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100592

Hermans, F., Sartas, M., Van Schagen, B., Van Asten, P., & Schut, M. (2017). Social network analysis of multi-stakeholder platforms in agricultural research for development: Opportunities and constraints for innovation and scaling. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0169634. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169634

HLPE. (2018). Multi-stakeholder partnerships to finance and improve food security and nutrition in the framework of he 2030 Agenda. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/cfs/cfs-hlpe/publications/hlpe-13/en

Hofmann, J. (2016). Multi-stakeholderism in Internet governance: Putting a fiction into practice. Journal of Cyber Policy, 1(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/23738871.2016.1158303

IFPRI. (2021). Global Food Policy Report: Transforming Food Systems after COVID-19. Retrieved from Washington DC: https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/collection/p15738coll2/id/134343

Ingram, J., & Thornton, P. (2022). What does transforming food systems actually mean? Nature Food, 3(11), 881–882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00620-w

IPES-Food. (2023). Who’s Tipping the Scales? The growing influence of corporations on the governance of food systems, and how to counter it. Retrieved from https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/tippingthescales.pdf

Kalibata, A. (2020). Fixing the world's food systems: A problem we must solve together. African Business, (476), 48–50. Retreived from: https://african.business/2020/09/energy-resources/agnes-kalibata-fixing-the-worlds-food-systems-a-problem-we-must-solve-together. Accessed on 23 Jul 2024

Klein Woolthuis, R., Lankhuizen, M., & Gilsing, V. (2005). A system failure framework for innovation policy design. Technovation, 25(6), 609–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2003.11.002

Kumu. (2023). Retrieved from Retrieved from https://kumu.io

Lacy-Nichols, J., & Williams, O. (2021). "Part of the solution:" Food corporation strategies for regulatory capture and legitimacy. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10(12), 845–856. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2021.111

Lauber, K., Ralston, R., Mialon, M., Carriedo, A., & Gilmore, A. B. (2020). Non-communicable disease governance in the era of the sustainable development goals: A qualitative analysis of food industry framing in WHO consultations. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00611-1

Lauber, K., Rutter, H., & Gilmore, A. B. (2021). Big food and the World Health Organization: A qualitative study of industry attempts to influence global-level non-communicable disease policy. BMJ Global Health, 6(6), e005216. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005216

Leeuwis, C., Boogaard, B. K., & Atta-Krah, K. (2021). How food systems change (or not): Governance implications for system transformation processes. Food Security, 13(4), 761–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01178-4

Lelieveldt, H. (2023). Food industry influence in collaborative governance: The case of the Dutch prevention agreement on overweight. Food Policy, 114, 102380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102380

McKeon, N. (2017). Are equity and sustainability a likely outcome when foxes and chickens share the same coop? Critiquing the concept of multistakeholder governance of food security. Globalizations, 14(3), 379–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2017.1286168

Mesiranta, N., Närvänen, E., & Mattila, M. (2022). Framings of food waste: How food system stakeholders are responsibilized in public policy debate. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 41(2), 144–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/07439156211005722

Montenegro De Wit, M., Canfield, M., Iles, A., Anderson, M., McKeon, N., Guttal, S., ... Prato, S. (2021). Editorial: Resetting power in global food governance: The UN Food Systems Summit. Development, 64(3–4), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-021-00316-x

Njotto, L. L. (2018). Centrality measures based on matrix functions. Open Journal of Discrete Mathematics, 08(04), 79–115. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojdm.2018.84008

Obstfeld, D. (2005). Social networks, the tertius iungens orientation, and involvement in innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(1), 100–130. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2005.50.1.100

Osei-Amponsah, C., van Paassen, A., & Klerkx, L. (2018). Diagnosing institutional logics in partnerships and how they evolve through institutional bricolage: Insights from soybean and cassava value chains in Ghana. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 84, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2017.10.005

Oxfam International. (2023). About GROW. Retrieved from https://www.oxfam.org/en/about-grow

Pel, B. (2016). Trojan horses in transitions: A dialectical perspective on innovation ‘capture.’ Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 673–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1090903

Sethi, S. P., & Schepers, D. H. (2014). United Nations global compact: The promise–performance gap. Journal of Business Ethics, 122, 193–208.

Siddiki, S. N., Carboni, J. L., Koski, C., & Sadiq, A.-A. (2015). How policy rules shape the structure and performance of collaborative governance arrangements. Public Administration Review, 75(4), 536–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12352

Slater, S., Serodio, P., Lawrence, M., Wood, B., Van den Akker, A., & Baker, P. (2024). The rise of multi-stakeholderism, the power of ultra-processed food corporations, and implications for global food governance: a network analysis. Agriculture and Human Values. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-024-10593-0

Smith, A., Fressoli, M., & Thomas, H. (2014). Grassroots innovation movements: Challenges and contributions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 63, 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.025

Sorvino, C. (2022). Forbes Global 2000: The World’s Largest Food Companies In 2022. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/chloesorvino/2022/05/12/the-worlds-largest-food-companies-in-2022/

Sustainable Food Lab. (2023). Sustainable Food Lab: Members & Leadership Circle. Retrieved from https://sustainablefoodlab.org/the-food-lab/member-advisory-board/

Suzuki, M., Webb, D., & Small, R. (2021). Competing frames in global health governance: an analysis of stakeholder influence on the political declaration on non-communicable diseases. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.257

Swinburn, B. A., Kraak, V. I., Allender, S., Atkins, V. J., Baker, P. I., Bogard, J. R., ... Dietz, W. H. (2019). The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The lancet commission report. The Lancet, 393(10173), 791–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8

The World Bank. (2023). World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Retrieved from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

Turner, J. A., Horita, A., Fielke, S., Klerkx, L., Blackett, P., Bewsell, D., ... Boyce, W. M. (2020). Revealing power dynamics and staging conflicts in agricultural system transitions: Case studies of innovation platforms in New Zealand. Journal of Rural Studies, 76, 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.022

Turnheim, B., & Sovacool, B. K. (2020). Forever stuck in old ways? Pluralising incumbencies in sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 35, 180–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.10.012

UNSCN. (2023). UNSCN Home Page. Retrieved from https://www.unscn.org/

Van Bers, C., Delaney, A., Eakin, H., Cramer, L., Purdon, M., Oberlack, C., ... Vasileiou, I. (2019). Advancing the research agenda on food systems governance and transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 39, 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.08.003

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press.

Weber, K. M., & Rohracher, H. (2012). Legitimizing research, technology and innovation policies for transformative change: Combining insights from innovation systems and multi-level perspective in a comprehensive ‘failures’ framework. Research Policy, 41(6), 1037–1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.015

World Business Council for Sustainable Development. (2019). Project outline: Global Agribusiness Alliance (GAA). Retrieved from https://docs.wbcsd.org/2019/01/1_pager/Global_Agribusiness_alliance.pdf

World Business Council for Sustainable Development. (2023). WBCSD - Our members. Retrieved from https://www.wbcsd.org/Overview/Our-members/Members

Funding

This study has been funded through PhD funding from the University of Bath, in affiliation with the SPECTRUM consortium (MR/S037519/1). SPECTRUM is funded by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (UKPRP). UKPRP is an initiative funded by the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Natural Environment Research Council, Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), The Health Foundation and Wellcome Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG obtained the funding for the work; AvdA, AF, AG and HR contributed to the conception and design of the work; AvdA and SS contributed to data collection and analysis; AvdA wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors have edited drafts of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Akker, A., Fabbri, A., Slater, S. et al. Mapping actor networks in global multi-stakeholder initiatives for food system transformation. Food Sec. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-024-01476-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-024-01476-7