Abstract

Emergency cash transfers provide essential life support to vulnerable households affected by a crisis, including those living in chronic poverty. So far, project life cycles, nutrition, and asset-related thresholds have informed the decision of when beneficiaries switch from emergency cash transfers to an income-generating livelihoods program. However, factors beyond material poverty influence the likelihood of sustained improvements in well-being during such changes. We argue that a food systems perspective with additional metrics helps provide targeted transition support to beneficiaries. Based on insights gained from an Urban Safety Net in Mogadishu, Somalia, we suggest a multi-level framework to conceptualise the transition readiness of internally displaced people and poor host communities. Based on this framework, we make recommendations for improving safety net programming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Emergency cash transfers have become a standard in emergency response (Adams & Winahyu, 2006; Doocy & Tappis, 2017; Harvey, 2007). Often provided by aid agencies, emergency cash transfers stabilize household consumption (Bailey & Hedlund, 2012) and protect assets against being sold to meet basic needs (Burchi et al., 2018). They also alleviate liquidity constraints (Barrientos, 2012), and in some cases, support savings and investment in small businesses (Angelucci & De Giorgi, 2009; Angelucci & Di Maro, 2015; Bernier & Meinzen-Dick, 2014). Hence, during quickly evolving crises in the absence of a functional state and insurance, emergency cash transfers substitute core functions of social protection systems (Doocy & Tappis, 2017), improve the resilience of beneficiaries (Barrientos, 2012; Sadoulet et al., 2001), enhance social capital and spillovers to non-beneficiary households via loans, gifts and remittances (Angelucci & De Giorgi, 2009; Angelucci & Di Maro, 2015). Compared to food aid, cash transfers contribute to the local economy (Brewin, 2008). In 2019, about US$5.6 billion in global humanitarian assistance was provided through cash and voucher assistance. This amount represents a twofold increase from 2015 (Lyles et al., 2021).

Despite the benefits, emergency cash transfers to beneficiaries tend to be time-bound. There are many reasons for cash transfers to end, such as the funding limitation of the donor, self‐selecting out of a program, termination due to non‐compliance, and changing eligibilities (Ladhani & Sitter, 2020). Not uncommon are predefined exits and administrative choices that end cash transfers. For example, beneficiaries leave a program when there is no longer a minor in the household (age limit) or after reaching the maximum number of years in the program (time limit). Exit criteria also include the nutrition status of households, income, or asset-related variables that tell whether a politically defined wellbeing threshold has been exceeded (Browne, 2013). Although pragmatic, exits informed by project necessities or material thresholds do not necessarily guarantee that beneficiaries leave cash transfers to sustainable livelihoods.

Beneficiaries experience heterogeneous livelihood transitions when exiting from a cash transfer program. The nature of these experiences often depends on household characteristics, assets, family dynamics and the external environment (Sabates-Wheeler et al., 2018). Consequently, some beneficiaries respond well to phasing out cash transfers while others do not. Against this background, we believe that sustainable transitions of beneficiaries depend on the ability of households to invest in new livelihoods while protecting themselves from post-program shocks. Doing so requires safety nets to consider individual, family-based, and contextual preconditions of beneficiaries for reducing vulnerability. A comprehensive understanding of transitions would guide emergency cash transfers to profile and monitor beneficiaries. In such a way, transition support can be offered more targeted to beneficiaries during cash transfers, at the actual exit, and post-program.

Monitoring and evaluation data collected from beneficiaries by cash transfer providers already captures relevant metrics. However, the metrics tend to be used to determine the point of graduation of beneficiaries out of poverty or vulnerability. Nonetheless, graduation conceptualised as an exogenous exit of participants from cash transfers after crossing a pre-set income threshold or escaping extreme poverty (Devereux & Sabates-Wheeler, 2015) is not applicable in chronic emergency contexts such as Somalia with extreme trauma, shattered lives, and livelihoods. So is sustainable graduation – defined as the achievement of long-term improvements in livelihoods and living conditions that are maintained across generations (Connolly-Boutin & Smit, 2016; Roelen, 2015). Instead, we conceptualize ‘graduation’ as a transition from emergency aid to a livelihood program that takes place within a more extensive food system. We argue that for such a transition to be successful, we must not only use poverty data to decide on the right moment. Equally important are dynamics within the communities and the larger transition context that all influence the ability of a person to transition into a livelihood program successfully and sustainably. This calls for widening the boundaries of transition assessments to go beyond traditional monitoring and evaluation data.

Nevertheless, a central question remains: How can aid programs predict whether households will achieve a sustained improvement in their well-being once they have dropped out of emergency cash transfers, transitioned into a livelihoods program, or shifted to a state-managed social protection system? An answer to this question requires a multi-level framework with material and non-material metrics. The framework we propose in this paper will enable program managers working in chronic emergencies to profile beneficiaries regarding their ability to transition from an emergency cash transfer program to a new livelihood strategy such as a government social protection system. Having such a framework provides several benefits. First, aid agencies could target the disbursement of entitlements more efficiently to specific transitional needs of beneficiaries. Second, the probability of successful transitions between and out of the program potentially increases. Third, a more differentiated approach to transition support through tailored accompanying measures could increase the overall effectiveness and efficiency of emergency cash transfer programming. Ultimately, the framework can help program managers to develop a rating system that ensures fairness in decision-making.

Against this background, we present such a multi-level framework to conceptualise the transition readiness of beneficiaries in internationally funded emergency cash transfer programs. This framework aims to understand better the changes beneficiaries experience during livelihood transitions in response to cash transfers. Consequently, the framework will aid assessments of the capability of beneficiaries to transition from emergency response to livelihood rebuilding in fragile, conflict-prone urban food systems. The framework also provides entry points for safety net programs to identify complementary support. This support shall increase livelihood transitions, contributing to nutrition, economic, and environmental impact. Although we derived our framework from work in Mogadishu, Somalia, we hope it becomes applicable to similar fragile contexts across Africa.

2 Methodology

2.1 Context

Globally, 43.1 million people are displaced (Padovese & Knapp, 2021). In 2013, 36% of the 28 million new internal displacements caused by conflict and disasters occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa (Seal et al., 2021). Somalia is among these countries.

Somalia faces extreme droughts and floods (Augustine & Kimbro, 2021; Maystadt & Ecker, 2014; Warsame et al., 2021), ethnic tensions and transboundary conflicts (Majid & Abdirahman, 2021; Menkhaus, 2017). The problems are often compounded by political marginalization, resulting in the hindrance of asset accumulation, income generation, human capital formation, and food and nutrition security (Hoehne, 2017). More than 70 percent of the Somali population lives on less than US$1.90 PPP (2011) per day (Hanmer et al., 2021), and about half of the population requires humanitarian assistance (OCHA, 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic and desert locusts amplified the fragility of rural and urban livelihoods. These fragilities exacerbated the severity of food insecurity, leading to a spike in pre-existing vulnerabilities, a disruption of economic activities, especially for low-income earners (WFP, 2020). Natural disasters, conflicts and livelihood insecurity led many people to migrate to rural and urban areas. About 2.6 million people are internally displaced in Somalia (Mohamed et al., 2021). Consequently, about 3.7 million people need social protection-related support (OCHA, 2019).

Safety nets are particularly crucial in Mogadishu, the capital city of Somalia. Mogadishu is home to about 497,000 internally displaced people (Braam et al., 2021). In 2018, WFP rolled out its first urban safety net program in Mogadishu, targeting 125,000 urban poor and internally displaced persons with an emergency cash transfer of $105 quarterly ($35 per month). WFP transfers cash through mobile money and caters for 50% of the food basket expenditure for an average family of six members. The program targets vulnerable families with disabilities, elderly people, and children and women enrolled in malnutrition treatment.

By 2020, about 1000 households had transitioned into a livelihood program with additional benefits such as micro-enterprise training and business start-up tool kits. WFP coordinates with state and non-state actors to generate synergies as the organization considers building the resilience of livelihoods to food and nutrition insecurity, poverty, and multidimensional vulnerability through strengthening national social protection systems. The transition readiness framework we present in this paper contributes to programming and operational arrangements to enable sustainable transitions out of emergency cash transfers.

2.2 Framework development

Beneficiaries transitioning from emergency cash transfers to an income-generating livelihoods program experience comprehensive changes at economic and social levels. Sustaining program gains after the exit of beneficiaries requires a broad understanding of the origins of poverty and vulnerability to derive a holistic approach to tackle the systemic and structural threats to lives and livelihoods. A growing body of literature links vulnerability, risk and shocks with productive capacity and wellbeing in low-income settings (Holzmann & Kozel, 2007). Therefore, factors that enable households to withstand or cope with risks and shocks can support an economically safe transition out of emergency cash transfer programs. We developed this framework and then triangulated it with WFP monitoring and evaluation insights, and expert conversations with social safety net experts in Mogadishu and Nairobi.

When conceptualising the framework, we also drew on post-distribution monitoring (PDM) variables that WFP Somalia uses to track changes in response to wet feeding and cash transfers. Many of these variables are standardized (e.g., food consumption and dietary diversity scores and livelihood coping strategy indices). We then complemented PDM variables with specific metrics relevant to transition readiness (e.g. aspirations, stress and self-efficacy) as proxies for human agency. We tested the internal logic of the framework through conversations with social protection and livelihood transition experts.

Finally, we conceptualised transition readiness from emergency cash transfers within the context of food systems. This is because food system dynamics positively or negatively influence the transition readiness of beneficiary households. We, therefore, reviewed and drew on the food systems framework developed by the HLPE (HLPE, 2017; HPLE, 2020) and drew lessons from frameworks detailing food systems transformation (Borman et al., 2022; Herens et al., 2022; Nordhagen et al., 2022).

3 Framework for understanding transitions

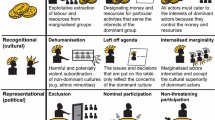

We conceptualise change from emergency aid to rebuilding livelihoods as a transition. A multitude of factors influence a household's capability to transition from emergency relief to a livelihoods program. Some of these factors are affected by emergency response directly. Others are linked to the larger food system outside the direct influence of emergency aid. Figure 1 presents the transition framework.

Transition readiness framework (informed by HLPE, 2017, own presentation)

Our framework builds on transition concepts widely used in sustainability research (El Bilali et al., 2019; Mottet et al., 2020) and agri-food system transformation research (Galli et al., 2020; Hebinck et al., 2021). In its simplest form, a transition describes the multi-level change a person experiences (i.e. changing expectations, assets, coping responses, and outcomes) between two points in time. Shifting from an emergency cash transfer to a livelihoods program, for example, represents such a multi-level transition. Transition theories emphasize that change is always systemic (Bui et al., 2019). In other words, sustainable livelihood transitions require solutions to the systemic problems of labour, food, input and output markets, and family and community cohesion.

.Our framework defines transition readiness as the ability of a household to engage in multi-level change triggered when graduating from an emergency relief program to a livelihood support program. It does not matter if the change is externally induced, for instance, through a sudden event, an opportunity or crisis, or motivated by internal thought and decision-making. Relatedly, an emergency cash transfer beneficiary is ready to switch or leave a program if he or she has developed the necessary capabilities and skills, including access to relevant resources, to actively engage in a robust remunerative livelihood and the ability to cope with stress and community dynamics. In other words, material and non-material conditions must be in place for beneficiaries to leave the program without risk of future loss of program gains. We call this transition readiness. Table 1 presents key concepts upon which our framework is built.

We distinguish five interdependent components in the transition framework. The succeeding sections of this chapter provide an overview of each of the five framework components.

3.1 Transition context

The transition context summarises external structures and processes that influence transitions. Some of these structures and processes support, while others hinder transitions. For example, the food price index and inflation rates impact beneficiaries' purchasing power and the utilisation of cash transfers. This, in turn, is reflected in fluctuating food consumption scores – a proxy indicator of household caloric availability. Also, the severity of food emergencies measured by the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) provides critical contextual information about the broader food security situation.

Smooth transitions from emergency cash transfers require policy prioritisation of resources to support market institutions – supply-side incentives and empowerment measures of the demand side – purchasing power. Finding the right mix of these incentives and regulations is a precursor for the transition readiness of beneficiaries.

Relatedly, cash transfer intending to enhance maternal health outcomes cannot achieve its objectives without a good health infrastructure, i.e. the availability and quality of health services and providers (de Brauw & Peterman, 2020; Powell-Jackson & Hanson, 2012). Also, demand-side educational interventions will likely not achieve the desired outcomes unless they are implemented in coordination with supply-side interventions (de Hoop et al., 2019). The demand and supply nexus makes the household location a critical context variable that shapes transition readiness.

The residential status of the beneficiary (determines rights, privileges and opportunities available to household members, thus affecting the potential for positive change) and the location are critical context variables that shape the transition readiness of a beneficiary and the household. In Mogadishu, the closer the beneficiary is to the city centre, the higher the ability to find work. Conversely, the further away from the city centre, the bigger the security risks and the smaller the remunerative livelihood opportunities.

Similarly, we propose understanding transitions in light of the coordination among international humanitarian and development actors providing cash assistance and longer-term aid in the same territory. For example, a unified identifier of beneficiaries helps provide targeted emergencies and complementary measures to enhance transition readiness. Finally, the overall security situation limiting movements of beneficiaries, humanitarian agencies, and the government influence access to food markets, employment, and critical services, hence influencing the transition of beneficiaries to alternative livelihoods.

3.2 Household capabilities

The transition capabilities of the household are central to the ability of households to transition from emergency relief to rebuilding livelihoods. We assess transition capabilities from the perspective of the household, often represented by the household head. We identify three domains (human agency, system performance, and access to enablers) because they drive the household's ability to transition from emergency relief to rebuilding livelihoods.

3.2.1 Human agency

We define agency as the capacity of an individual or a household to make livelihood choices and follow through with these choices in their respective transition context. Human agency is the combined effect of human aspiration, health, food and nutrition, assets, and livelihood strategies.

Aspiration (goal orientation and trust in oneself)

Aspirations-based utility theories suggest that aspirations play a central role in the decision-making of poor people (Lybbert & Wydick, 2016; Wydick, 2018). Although people's time horizon in emergency cash transfer programs tends to be short, longer-term aspirations of households improve with time (Malhi, 2020; Mausch et al., 2018). Educational aspirations, for instance, are impacted by cash transfers through relaxing household budget constraints, changing perceptions on the returns to education (increased exposure to positive role models), and reducing marginal costs of college attendance (García et al., 2019; Whetten et al., 2019). Drawing from (Glewwe et al., 2015), we posit that aspirations enhance trust in oneself– self-efficacy influencing daily livelihood efficacy and efficacy to engage in remunerative activities that smoothen transitions. We consider the efficacy of managing risks and uncertainties, including the volatile security context, an essential condition for transitions.

Health (mental and physical)

IDPs and vulnerable households often face health challenges that influence the sustainability of livelihood transitions. Therefore, we appraise the extent to which a household member has been sick and felt the need for medical care at a clinic or hospital. The higher the number of health incidents uncovered by financial means of the household, the lower the transition readiness.

Cash transfers affect psychological wellbeing. In particular, they increase happiness and life satisfaction and reduce stress and depression (Haushofer & Shapiro, 2016). Psychosocial wellbeing has positive impacts on educational performance, participation in social life and empowerment for decision-making (Attah et al., 2016), while the lack of it restricts the 'ability of people to achieve the things expected of them and what they expect of themselves, leading to feelings of shame and ultimately withdrawal, depression and 'reductions in personal efficacy' (Walker et al., 2013).

The person’s assessment of the type, controllability of the stressor and the resources available to respond to the stressor mediates psychological stress (Folkman et al., 1986). In other words, self-esteem and self-efficacy are correlated with psychological distress and can determine social and economic success (Baird et al., 2013; Krishnan & Krutikova, 2013). The higher the stress, the lower the ability to allocate resources to remunerative livelihoods or employment. Therefore, we look for signs that beneficiaries feel unable to control the essential matters in their lives and feel unconfident about handling personal problems. This affects participation in income-generating activities.

Food security and nutrition

Cash transfers can alleviate monetary poverty (Burchi et al., 2018) and regularize consumption without adopting negative coping strategies (Covarrubias et al., 2012). Through improvement in women's empowerment and involvement in household decision-making (Barrientos, 2007), cash transfers improve food security and nutritional status of households (Bassett, 2008). Better household food security can ignite or enforce risk-taking behaviour, with beneficiaries engaging in more productive businesses or adopting more advanced agricultural practices following assured reliance on the program for consumption. Therefore, stable food consumption is a prerequisite for transition readiness.

The framework uses food consumption scores, dietary diversity scores, and food expenditure shares. We hypothesise, for example, that the higher the food expenditure share, the higher the poverty level and the lower the food security and potential for a smooth transition. Also, the food source is important for transition readiness predictions (e.g. the relief food/purchase/production ratio).

Productive assets and income

Cash is necessary for economic transformation (Alatinga et al., 2020). Cash transfers alleviate liquidity and risk constraints associated with household investments (Schwab, 2019). For example, cash transfers to farmers increase agricultural production through increased livestock holding and crop production (Ambler et al., 2020).

Increased investment, ownership and profitability of farm and non-farm businesses; reductions in household debt levels; increases in household savings; and significant shifts in labour supply from agricultural wage labour to better and more desirable forms of employment have been linked to cash transfers (Daidone et al., 2014) leading to higher incomes and potential for a smooth transition.

More assets support household production for own consumption and trade, increasing income and resilience to shocks. The higher the assets, the bigger the absorption potential, cumulative effects, and potential for transition. A precondition for successful transitions within a safety net program is that household assets remain intact. We consider total and non-food household expenditures as proxies for household income from various sources (earnings, remittances, transfers).

Livelihood strategies

Livelihood strategies of beneficiaries typically comprise progress and distress strategies. The higher the coping strategy index, the lower the likelihood of successful transitions within safety nets. For example, when households fall short in food, some reduce the number of meals, reduce meal sizes and switch to more affordable, often low-quality foods. Poor eating has direct, negative consequences for the ability to work and human health. As such, the degree to which a household must deploy coping strategies has direct consequences for transitions and the agency of the household.

3.2.2 System performance

Safety net beneficiaries in Mogadishu are embedded in larger social systems of family dynamics, communities, market institutions and related norms, values, and beliefs. The extent to which beneficiaries perceive the social system as performing well directly influences their transition readiness. Therefore, measuring the system performance from the household's perspective constitutes the second transition readiness domain.

Social dynamics

Household dynamics and men’s and women's decision-making influence human agency relevant to transitions. The more targeted a safety net program supports individuals in developing their agency, the higher the likelihood of a successful transition from emergency relief to a livelihoods program. Women often face structural challenges limiting their transition ability. Conversely, female-headedness could improve women's ability to control and allocate resources, positively impacting household food security. When cash transfers are shared among household members, the total value declines. A good understanding of household dependencies matters.

Social dynamics within communities can either offset limitations in human agency or reduce the effects of the agency. Awareness of rights and entitlements emboldens beneficiaries to challenge unacceptable behaviour by officials and make collective demands that may enhance transitions (Molyneux et al., 2016). Social connectivity can generate social congruence and utility. Therefore, the construct of the community in terms of traditions, norms, social gatherings, self-help groups and the beneficiaries' membership and participation in these associations can be an essential source of social capital both for the success of recipients' investment (if any) and the protection against shocks or act as a springboard for recovery from a shock. For example, with the absence of an effective governance structure in Somalia since 1991, clan affiliation became a critical source of social, financial, and human protection (Hanmer et al., 2021). In the transition readiness framework, we regard system performance as crucial because factors within that category mediate access to and the performance of human agency.

Access to markets (food markets, input markets, job markets)

Markets and market institutions influence a person's access to agricultural inputs, output markets, food, and employment. The more enabling the market supporting livelihood strategies, the more able households are to derive remuneration (Sabates-Wheeler et al., 2018). The ability to navigate volatile food and job markets, for example, may become a transition enabler for safety net beneficiaries. Markets that work well and are within reach of beneficiaries could accelerate transitions between emergency relief and the livelihood program.

Vulnerability perception (security, stability, risk)

The vulnerability framework entails all risks, potential shocks, and uncertainties beneficiaries experience before and during a transition. In Mogadishu, this framework entails accessing neighbourhoods and services depending on risks. Equally crucial for a successful transition is access to a relatively stable, risk-mitigating environment. Such considerations are especially relevant in post-conflict regions and generally fragile areas.

3.2.3 Access to enablers

The ability of households to access specific support services supporting the transition constitutes the third domain of transition capability.

Training

Transition support services such as seed capital/start-up tools and micro-entrepreneurship mentorship (skills training) packages encourage investment and enhance the resilience of program beneficiaries to shocks. These protect assets from distress sales to meet consumption needs, pushing households back into destitution and low levels of well-being shortly after program participation. The higher the support services of livelihood transitions, the higher the probability of positive change.

Transition finance

The better the access to financial services, the more enabling the transition context. How a household can access transition-specific financial services influences their transition readiness. Services may include formal microcredit institutions and informal saving groups.

Health services

Access to health services during and after transitions will influence the transition outcomes. Factors that influence access to health backup include the household's physical location, liquidity, and affordable health services in the area. Also, intrahousehold dynamics and gender play a role in accessing general health back up.

3.3 Safety nets

Unlike productive safety nets that include livelihood support as a program component (Sengupta, 2012), emergency cash transfers are time-bound. We posit that including beneficiary-tailored livelihood programs will improve the overall impact of emergency safety net programs. The transition readiness framework identifies safety net programming as the central instrument to support transitions. We identify three broad levers. First, social transfers of food and cash. This includes (cash payment modalities, digital currency, timing, frequency, transfer amounts, recipient), which all can influence the transition readiness of the household.

Second, complementary support (e.g. fee waivers, subsidies, insurance, job-search services). Complementary support refers to the bundle of measures offered with cash transfers by the government, civil society, and the private sector. For example, Mexico's Oportunidades (Barrientos & Santibáez, 2009) and projects in Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, India, Pakistan, and Peru (Banerjee et al., 2015) combine cash transfers with nutrition, schooling, health, training and support, job search, youth inclusion, saving instruments, life skills coaching and micro-enterprise development, which increases the probability of households attaining and sustaining higher living standards after transitioning off the program.

In Mogadishu, start-up toolkits for entrepreneurship and salary support to small and medium-sized companies (i.e. promoting labour market participation) could increase the ability of beneficiaries to find employment and generate income. Digital inclusion and behaviour adaptation through short messaging services could support the transitions of households. The introduction of social insurance for health or disability supports the transition readiness of households.

Finally, structural reforms, including support towards labour markets, such as supporting the government to offer job mentoring and coaching over at least one year are essential for emergency support – rebuilding livelihood transition. Also, lowering borrowing thresholds by banks could be negotiated specifically targeting transitioning beneficiaries. The quality and effectiveness of delivery systems influence complementarity support and, thus, transition readiness.

3.4 Transition pathways

Transition pathways represent the core of the change in response to participating and moving in between programs within an urban safety net. However, households experience transitions differently. There is considerable diversity in transition capabilities within households, across and within communities concerning their natural, physical, financial, human, and social capital. This difference in assets, needs and objectives among households affects their responses to cash transfers, thus aiding or limiting their potential to transition. Some households intentionally save and invest in productive assets (Daidone et al., 2014), while for others, saving and investment are household coping strategies to reduce consumption risk and vulnerability (Schwab, 2019). In such a way, basic measures such as food consumption scores, food expenditure shares and self-efficacy perceptions of households’ change. A decline in these measures does not always mean a negative transition outcome. Typical transition pathways include a gradual increase in assets, hanging in, stepping up and stepping out (Dorward et al., 2009).

Three broad drivers influence pathways. One, developmental influences resulting from specific changes in the personal factors of the beneficiary, such as lifecycle challenges of old age, illness, or disability. Two, organizational influences resulting from changes in the operating environment; for instance, the intra-organizational changes in structure, function and dynamics of the implementing body and changes in the broader social, political, or economic environment. Examples include changes in program eligibility criteria, labour markets, security and government policy, ethnic tensions, and economic recession. Three, situational influences may be marriage, migration, getting a job/career change, business start-up, completing an education level, homelessness, widowhood and divorce or separation.

Pathways are complex, multi-level changes of households and their context, hence encompassing a combination of several smaller, intertwined transitions. These transitions set in and conclude at different points during the program. Some reinforce each other positively, others are antagonistic. For example, the transition between livelihood strategies may be set in relatively early in the change process. Then, depending on the first transition outcomes, mental health transitions may set in, and, depending on their nature, enforce or become a barrier to the ongoing livelihood transition.

Pathways vary according to the type of transition. A transition within a safety net, for example, from one cash transfer modality to another, differs from shifting from recovery to an employment scheme. Also, transitions between programs and final exit from a cash transfer trigger very different experiences in beneficiaries. The nature of transitions and the various transition pathways people experience influence transition outcomes.

3.5 Transition outcomes

Transition outcomes are central to the transition readiness framework. For example, programs affect the ability of a household to prepare for, cope with, and adapt to post-program shocks, protect the family's well-being, and avoid the poverty trap or fall back into pre-program poverty differently (Bowen et al., 2020). The actual transition between or out of the program results in outcomes for households and their communities.

Central transition outcomes include the increase in the transformative capacity of individuals, households and communities resulting from program impacts in health (e.g. better nutrition and health of family members); education (e.g. more school enrolments, increased attendance and reduced dropouts), enhanced family relations (e.g. women empowerment, increased autonomy and gender equity between men and women), and community-level transformation through social inclusion, social capital, trust and community-level empowerment increases are all transition outcomes.

In the long term, these outcomes create an impact in the domain of food and nutrition, asset accumulation, independence, and overall social-psychological well-being. Indirectly, these outcomes influence food systems. The impact is generated through pathways such as the alleviation of credit, savings and liquidity constraints, and the enhancement of economic progress via an increase of certainty and access to technology, knowledge and financial services (Barrientos, 2012; Soares et al., 2016; Tirivayi et al. 2013, 2016). Regular and predictable cash transfers have been linked to enhanced investments in livestock and crop production and strong positive impacts on household food consumption through increases in the quantity and quality of food and reduction in the prevalence of food insecurity (Daidone et al., 2014; Tiwari et al., 2016).

3.6 Analysing interactions

The framework serves as an overarching way of conceptualizing feedback between the five system components. Some feedback reinforces a pattern, other feedback loops disrupt and redirect. Age, gender, and education influence the person's transition within a safety net program. Younger household heads are more enterprising and more able to engage in remunerative activities than their older counterparts, and higher education levels improve their investment decision-making, which increases the potential for positive change (Sabates-Wheeler et al., 2018). Finally, the capabilities of a household must be understood in relation to the performance of the social system (i.e. dynamics within the family, community and society that support or hinder transitions) and access to transition-relevant support services.

4 Towards a transition support tool

While the transition readiness framework helps program managers conceptualise the emergency aid – livelihood rebuilding continuum, it is also the basis for transition readiness assessments of the beneficiary. Program managers can conduct such transition assessments using data from beneficiaries before the program, during the program, and after the emergency–livelihood program transition. Figure 2 presents a process model to manage transition assessments in an emergency safety net program.

4.1 Transition assessments

The transition assessments predict how beneficiaries transition from an emergency cash transfer sustainably. Program managers can draw on various quantitative and qualitative data to carry out transition readiness measurements. These include profiling, baseline and PDM data sets. Program managers can aggregate transition readiness indicators that capture beneficiaries' exposure, susceptibility, and adaptive capacity to post-program shocks to generate an index. Such a transition readiness index enables decision-makers to identify beneficiaries in a program with sufficient capabilities for a sustainable transition.

Program managers derive the indicators from the household capability component of the framework in Fig. 1. Single item questionnaire through which respondents answer binary questions (yes/no), questionnaires with rating scales for measuring transition readiness perceptions, divided into several subscales capture essential transition readiness attributes. Program managers can then triangulate survey results with qualitative data from a smaller, representative sample of beneficiaries. Clusters are one way to capture the variability of households and guide appropriate program interventions and social policy.

4.2 Contextualising assessments

To measure the transition readiness of a household or a community, program managers will structure the assessment in two stages: context assessments of transition and food environment and readiness analysis of households. Transition readiness measurements result in a score – the Transition Readiness Index (TRI). Since transition readiness is multidimensional, the perception of readiness may differ between the program management and the beneficiary. Therefore, verifying assigned transition readiness scores with beneficiaries’ assessment criteria is essential. Program managers must also understand the transition context and the food system context well. In such a way, the transition readiness measurement allows program managers to define contextualised impact pathways.

4.3 Transition readiness decisions

Transition readiness assessments should be an inclusive and regular activity throughout the program. The final transition decision depends on scores, conversations with beneficiaries and expert judgments. Although time-consuming, such conversations ensure the inclusiveness of programs. If done with beneficiaries, it provides instant feedback and encourages self-assessments of transition readiness. In other words, any transition readiness tool administered in coordination with clients helps them monitor their progress towards livelihood goals. Ideally, this process enhances agency and increases the adaptive capacity of beneficiaries.

5 Conclusion

Our framework supporting a data-driven understanding of transition readiness could become a realistic alternative to time, age, or income cut-offs that programs employ to terminate beneficiaries' participation. In this paper, we put together such a framework. Therefore, the medium-term aim is to verify the most important predictors of transition readiness. This will also imply the development of a rating systems to ensure fairness in decision-making by program managers.

Frameworks are conceptual representations of reality and thus have limitations. One is the still limited empirical evidence on how accompanying measures accelerate transitions. Also, the fluent security situation in conflict-prone environments is difficult to capture in such a framework. Further, feedback loops emerging from multiple domains in the framework can reinforce or hinder the transitions. Attributing single variables to selected outcomes and impacts remains difficult. At the same time, there is a risk of overloading the framework with variables and thus increasing its complexity. Finally, the framework is not meant to transition beneficiaries more quickly for economic reasons but to increase the transformative role of humanitarian aid through systematic safety net programming.

The framework helps to see the safety net program against the background of a larger food system. It helps in the theoretical reasoning of how cash transfers and accompanying measures enable sustainable transitions within safety net programs. The framework also supports coordinating effective programming across agencies, informs food and safety net policies, and makes transitions more applicable to emergency response in fragile contexts. Finally, we hope the framework motivates others to empirically test and help develop it in future.

References

Adams, L., & Winahyu, L. (2006). Learning from cash responses to the tsunamis: Case studies (Issue January 2007). Retrieved December 23, 2021, from http://search.proquest.com/docview/58759241?accountid=15181. http://www.odi.org.uk/hpg/papers/Cash_casestudies.pdf%5Cn. http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/4860.pdf

Alatinga, K. A., Daniel, M., & Bayor, I. (2020). Community experiences with cash transfers in relation to five SDGs: Exploring evidence from Ghana’s Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) programme. Forum for Development Studies, 47(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2019.1635524

Ambler, K., De Brauw, A., & Godlonton, S. (2020). Cash transfers and management advice for agriculture: Evidence from Senegal. World Bank Economic Review, 34(3), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhz005

Angelucci, M., & De Giorgi, G. (2009). Indirect effects of an aid program: How do cash transfers affect ineligibles’ consumption? American Economic Review, 99(1), 486–508. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.1.486

Angelucci, M., & Di Maro, V. (2015). Programme evaluation and spillover effects. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 8(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2015.1033441

Attah, R., Barca, V., Kardan, A., MacAuslan, I., Merttens, F., & Pellerano, L. (2016). Can Social Protection Affect Psychosocial Wellbeing and Why Does This Matter? Lessons from Cash Transfers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 52(8), 1115–1131.

Augustine, J. M., & Kimbro, R. T. (2021). Risk and resilience of Somali children in the context of climate change, famine, and conflict. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 12(1), 0–24. Retrieved December 08, 2021, from http://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk%5Cn. http://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol4/iss1/5

Bailey, S., & Hedlund, K. (2012). The impact of cash transfers on food consumption in humanitarian settings: A review of evidence. Overseas Development Institute (ODI), May.

Baird, S., de Hoop, J., & Özler, B. (2013). Income shocks and adolescent mental health. Journal of Human Resources, 48(2), 370–403. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.48.2.370

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Goldberg, N., Karlan, D., Osei, R., Parienté, W., Shapiro, J., Thuysbaert, B., & Udry, C. (2015). A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries. Science, 348(6236), 1260799. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260799

Barrientos, A. (2007). Understanding conditions in income transfer programmes: A brief(est) note. IDS Bulletin, 38(3), 66–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2007.tb00380.x

Barrientos, A. (2012). Social transfers and growth: What do we know? What do we need to find out? World Development, 40(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.012

Barrientos, A., & Santibáez, C. (2009). New forms of social assistance and the evolution of social protection in Latin America. Journal of Latin American Studies, 41(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X08005099

Bassett, L. (2008). Can conditional cash transfer programs play a greater role in reducing child undernutrition? (Issue 0835).

Bernier, Q., & Meinzen-Dick, R. S. (2014). Resilience and social capital. Building resilience for food and nutrition security, May 2014, 1–23. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/128152/filename/128363.pdf

Borman, G. D., de Boef, W. S., Dirks, F., Saavedra, Y., Subedi, A., Thijssen, M. H., Jacobs, J., Schrader, T., Boyd, S., Hermine, J., Van Der Maden, E. I., Assibey-yeboah, S., Moussa, C., Uzamukunda, A., Daburon, A., Ndambi, A., Vugt, S. Van, Guijt, J., & Willem, J. (2022). Putting food systems thinking into practice: Integrating agricultural sectors into a multi-level analytical framework. Global Food Security, 32(July 2021), 100591.

Bowen, T., del Ninno, C., Andrews, C., Coll-Black, S., Gentilini, U., Johnson, K., Kawasoe, Y., Kryeziu, A., Maher, B., & Williams, A. (2020). Adaptive social protection: Building resilience to shocks. International Development in Focus. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7878-8_4

Braam, D. H., Srinivasan, S., Church, L., Sheikh, Z., Jephcott, F. L., & Bukachi, S. (2021). Lockdowns, lives and livelihoods: The impact of COVID-19 and public health responses to conflict affected populations - a remote qualitative study in Baidoa and Mogadishu, Somalia. Conflict and Health, 15(47), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-021-00382-5

Brewin, M. (2008). Evaluation of concern Kenya’s Kerio Valley cash transfer pilot. In Concern Kenya (Issue July). http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:EVALUATION+OF+CONCERN+KENYA+’+S+KERIO+VALLEY+CASH+TRANSFER+PILOT#0

Browne, E. (2013). Post-graduation from social protection. In GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1035. www.gsdrc.org

Bui, S., Costa, I., De Schutter, O., Dedeurwaerdere, T., Hudon, M., & Feyereisen, M. (2019). Systemic ethics and inclusive governance: Two key prerequisites for sustainability transitions of agri-food systems. Agriculture and Human Values, 36(2), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09917-2

Burchi, F., Scarlato, M., & d’Agostino, G. (2018). Addressing food insecurity in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of cash transfers. Poverty and Public Policy, 10(4), 564–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.233

Connolly-Boutin, L., & Smit, B. (2016). Climate change, food security, and livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa. Regional Environmental Change, 16(2), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0761-x

Covarrubias, K., Davis, B., & Winters, P. (2012). From protection to production: Productive impacts of the Malawi Social Cash Transfer scheme. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 4(1), 50–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2011.641995

Daidone, S., Davis, B., González-Flores, M., Handa, S., & Seidenfeld, D. (2014). Zambia’s Child Grant Programme: 24-month impact report on productive activities and labour allocation. Retrieved September 21, 2020, from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3692e.pdf

de Brauw, A., & Peterman, A. (2020). Can conditional cash transfers improve maternal health care? Evidence from El Salvador’s Comunidades Solidarias Rurales program. Health Economics (United Kingdom), 29(6), 700–715. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4012

de Hoop, J., Morey, M., & Seidenfeld, D. (2019). No lost generation: Supporting the school participation of displaced syrian children in Lebanon. Journal of Development Studies, 55(sup1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1687875

Devereux, S., & Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2015). Graduating from social protection? Editorial Introduction. IDS Bulletin, 46(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12124

Doocy, S., & Tappis, H. (2017). Cash-based approaches in humanitarian emergencies: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–200. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2017.17

Dorward, A., Anderson, S., Bernal, Y. N., Vera, E. S., Rushton, J., Pattison, J., & Paz, R. (2009). Hanging in, stepping up and stepping out: Livelihood aspirations and strategies of the poor. Development in Practice, 19(2), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520802689535

El Bilali, H., Callenius, C., Strassner, C., & Probst, L. (2019). Food and nutrition security and sustainability transitions in food systems. Food and Energy Security, 8(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.154

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Gruen, R. J., & DeLongis, A. (1986). Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(3), 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.571

Galli, F., Prosperi, P., Favilli, E., D’Amico, S., Bartolini, F., & Brunori, G. (2020). How can policy processes remove barriers to sustainable food systems in Europe? Contributing to a policy framework for agri-food transitions. Food Policy, 96(March), 101871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101871

García, S., Harker, A., & Cuartas, J. (2019). Building dreams: The short-term impacts of a conditional cash transfer program on aspirations for higher education. International Journal of Educational Development, 64(November 2018), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.12.006

Glewwe, P., Ross, P. H., Wydick, B., Ave, B., Paul, S., Student, D., Todd, S., Carillo, J., Auker, T., Heryford, K., Rutledge, L., Ramirez, H., Zeballos, E., Sim, A., Bakir, M., & Zegarra, B. (2015). Developing hope: The impact of international child sponsorship on self-esteem and aspirations (No. 9; Econmics). Retrieved December 13, 2021, from http://www.jblumenstock.com/files/jsde/glewwe.pdf

Hanmer, L. C., Rubiano-Matulevich, E., & Santamaria, J. (2021). Differences in household composition hidden dimensions of poverty and displacement in Somalia. In Gender global theme (No. 9818; Issue October).

Harvey, P. (2007). Cash-based responses in emergencies. IDS Bulletin, 38(3), 79–81. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from www.odi.org

Haushofer, J., & Shapiro, J. (2016). The short-term impact of unconditional cash transfers to the poor: Experimental evidence from kenya. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4), 1973–2042. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw025

Hebinck, A., Klerkx, L., Elzen, B., Kok, K. P. W., König, B., Schiller, K., Tschersich, J., van Mierlo, B., & von Wirth, T. (2021). Beyond food for thought – Directing sustainability transitions research to address fundamental change in agri-food systems. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 41(July), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.003

Herens, M. C., Pittore, K. H., & Oosterveer, P. J. M. (2022). Transforming food systems: Multi-stakeholder platforms driven by consumer concerns and public demands. Global Food Security, 32((2022) 100592), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100592

HLPE. (2017). Nutrition and food systems. In High level panel of experts (Vol. 12, Issue September). Retrieved December 13, 2021, from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7846e.pdf

HPLE. (2020). Food security and nutrition: Building a Global narrative towards 2030. In High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE). Retrieved December 13, 2021, from http://www.fao.org/3/ca9731en/ca9731en.pdf

Hoehne, M. V. (2017). Between Somaliland and Puntland: Marginalization, militarization and conflicting political visions. In African affairs. (Vol. 116, Issue 462). Rift Valley Institute. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adw078

Holzmann, R., & Kozel, V. (2007). The role of social risk management in development: A World Bank view. IDS Bulletin, 38(3), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2007.tb00365.x

Krishnan, P., & Krutikova, S. (2013). Non-cognitive skill formation in poor neighbourhoods of urban India. Labour Economics, 24(2013), 68–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2013.06.004

Ladhani, S., & Sitter, K. C. (2020). Conditional cash transfers: A critical review. Development Policy Review, 38(1), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12416

Lybbert, T. J., & Wydick, B. (2016). Hope as aspirations, agency, and pathways: poverty dynamics and microfinance in Oaxaca, Mexico. In NBER working paper series. (Working Paper 22661; NBER Working Paper Series).

Lyles, B. E., Chua, S., Barham, Y., Pfieffer-Mundt, K., Spiegel, P., Burton, A., & Doocy, S. (2021). Improving diabetes control for Syrian refugees in Jordan: A longitudinal cohort study comparing the effects of cash transfers and health education interventions. Conflict and Health, 15(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-021-00380-7

Majid, N., & Abdirahman, K. (2021). The Jubbaland project and the transborder Ogadeen: Identity politics and regional reconfigurations in the Ethiopia-Kenya-Somalia borderlands Nisa. In Conflict research programme (Issue February).

Malhi, F. N. (2020). Unconditional cash transfers: Do they impact the aspirations of the poor? Munich Personal RePEc Archive, 102509. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/102509

Mausch, K., Harris, D., Heather, E., Jones, E., Yim, J., & Hauser, M. (2018). Households’ aspirations for rural development through agriculture. Outlook on Agriculture, 47(2), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030727018766940

Maystadt, J. F., & Ecker, O. (2014). Extreme weather and civil war: Does drought fuel conflict in Somalia through livestock price shocks? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 96(4), 1157–1182. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aau010

Menkhaus, K. (2017). Elections in the hardest places: The case of Somalia. Journal of Democracy, 28(4), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0073

Mohamed, A. A., Bocher, T., Magan, M. A., Omar, A., Mutai, O., Mohamoud, S. A., & Omer, M. (2021). Experiences from the field: A qualitative study exploring barriers to maternal and child health service utilization in idp settings somalia. International Journal of Women’s Health, 13, 1147–1160. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S330069

Molyneux, M., Jones, W. N., & Samuels, F. (2016). Can cash transfer programmes have ‘transformative’ effects? Journal of Development Studies, 52(8), 1087–1098. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1134781

Mottet, A., Bicksler, A., Lucantoni, D., De Rosa, F., Scherf, B., Scopel, E., López-Ridaura, S., Gemmil-Herren, B., Bezner Kerr, R., Sourisseau, J. M., Petersen, P., Chotte, J. L., Loconto, A., & Tittonell, P. (2020). Assessing transitions to sustainable agricultural and food systems: A Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation (TAPE). Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4(December), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.579154

Nordhagen, S., Lambertini, E., DeWaal, C. S., McClafferty, B., & Neufeld, L. M. (2022). Integrating nutrition and food safety in food systems policy and programming. Global Food Security, 32, 100593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100593

OCHA. (2019). Humanitarian needs overview - Somalia. In Humanitarian programme cycle 2020 (Issue December 2019). Retrieved December 13, 2021, from www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/nigeria

Padovese, V., & Knapp, A. (2021). Challenges of managing skin diseases in refugees and migrants. Dermatologic Clinics, 39(1), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2020.08.010

Powell-Jackson, T., & Hanson, K. (2012). Financial incentives for maternal health: Impact of a national programme in Nepal. Journal of Health Economics, 31(1), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.010

Roelen, K. (2015). The “twofold investment trap”: Children and their role in sustainable graduation. IDS Bulletin, 46(2), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12126

Sabates-Wheeler, R., Sabates, R., & Devereux, S. (2018). Enabling graduation for whom? Identifying and explaining heterogeneity in livelihood trajectories post-cash transfer exposure. Journal of International Development, 30(7), 1071–1095. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3369

Sadoulet, E., De Janvry, A., & Davis, B. (2001). Cash transfer programs with income multipliers: PROCAMPO in Mexico. World Development, 29(6), 1043–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00018-3

Schwab, B. (2019). Comparing the productive effects of cash and food transfers in a crisis setting: Evidence from a randomised experiment in Yemen. Journal of Development Studies, 55(sup1), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1687880

Seal, A. J., Jelle, M., Grijalva-Eternod, C. S., Mohamed, H., Ali, R., & Fottrell, E. (2021). Use of verbal autopsy for establishing causes of child mortality in camps for internally displaced people in Mogadishu, Somalia: A population-based, prospective, cohort study. The Lancet Global Health, 9(9), e1286–e1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00254-0

Sengupta, A. (2012). Pathways out of the Productive Safety Net Programme: Lessons from Graduation Pilot in Ethiopia.

Soares, F. V., Knowles, M., Daidone, S., & Tirivayi, N. (2016). Combined effects and synergies between agricultural and social protection interventions: What is the evidence so far? In Fifth transfer project research workshop: Evaluating national integrated cash transfer programs (Issue January). Retrieved October 08, 2020, from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6589e.pdf

Tirivayi, N., Knowles, M., & Davis, B. (2013). The interaction between social protection and agriculture A review of evidence. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 98.

Tirivayi, N., Knowles, M., & Davis, B. (2016). The interaction between social protection and agriculture: A review of evidence. Global Food Security, 10, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2016.08.004

Tiwari, S., Daidone, S., Angelita, M., Prifti, E., Handa, S., Davis, B., Niang, O., Pellerano, L., Quarles, P., Ufford, V., & Seidenfeld, D. (2016). Impact of cash transfer programs on food security and nutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: A cross-country analysis. Global Food Security, 11, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2016.07.009

Walker, R., Kyomuhendo, G. B., Chase, E., Choudhry, S., Gubrium, E. K., Nicola, J. Y., Lodemel, I., Mathew, L., Mwiine, A., Pellissery, S., & Ming, Y. (2013). Poverty in global perspective: Is shame a common denominator? Journal of Social Policy, 42(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279412000979

Warsame, A. A., Sheik-Ali, I. A., Ali, A. O., & Sarkodie, S. A. (2021). Climate change and crop production nexus in Somalia: An empirical evidence from ARDL technique. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(16), 19838–19850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11739-3

WFP. (2020). WFP Somalia Country Brief. February, 1–2.

Whetten, J., Fontenla, M., & Villa, K. (2019). Opportunities for higher education: The ten-year effects of conditional cash transfers on upper-secondary and tertiary enrollments. Oxford Development Studies, 47(2), 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2018.1539472

Wydick, B. (2018). When are cash transfers transformative? In UC Berkeley CEGA Working Papers (WPS-069; Vol. 15, Issue 4).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Nairobi, Kenya and the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets lead by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFRPI) for their financial support. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers as well as Clare Obrien and Frank Place for their helpful comments, and Serene Philip, Hiba Abouswaid, Naureen Andare, Chana Opaskornkul and WFP Somalia for their collaboration in finalising this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU). Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimers

None of the authors is employed by WFP. Concepts, statements, and opinions presented in this article may not be those of WFP.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hauser, M., Mugonya, J. Framework for conceptualising transition readiness from emergency response to rebuilding livelihoods in Mogadishu, Somalia. Food Sec. 16, 397–409 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-024-01431-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-024-01431-6