Abstract

Unhealthy diets are among the main risk factors associated with non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In Sub Saharan Africa, NCDs were responsible for 37% of deaths in 2019, rising from 24% in 2000. There is an increasing emphasis on health-harming industrial foods, such as ultra-processed foods (UPFs), in driving the incidence of diet-related NCDs. However, there is a methodological gap in food systems research to adequately account for the processes and actors that shape UPFs consumption across the different domains of the food systems framework and macro-meso-micro levels of analysis. This paper interrogates how the Food Systems Framework for Improved Nutrition (HLPE in Nutrition and food systems. A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security, 2017), considered the dominant framework to analyse nutrition, and language of interdisciplinarity are practised in research with regards to consumption of UPFs among adolescents in Ghana, a population group that is often at the forefront of dramatic shifts in diets and lifestyles. We conducted a scoping review of studies published between 2010 and February 2022, retrieved 25 studies, and mapped the findings against the domains and analysis levels of the Food Systems Framework for Improved Nutrition (HLPE in Nutrition and food systems. A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security, 2017). Our study illustrates that there is a tendency to address unhealthy diets among adolescents in a siloed manner, and as a behavioural and nutritional issue. In most cases, the analyses fail to show how domains of the food systems framework are connected and do not account for linkages across different levels of analysis. Methodologically, there is a quantitative bias. From the policy point of view, there is a disconnect between national food policies and food governance (i.e., trade and regulations) and initiatives and measures specifically targeted at adolescent’s food environments and the drivers of UPFs consumption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

In recent years, high profile reports such as the Sustainable Food Systems Framework for Improved Nutrition (HLPE, 2017) have advocated for interdisciplinary approaches and systems thinking to address the complexities of food systems and the pressing malnutrition challenges at hand. The 2017 HLPE Framework builds on earlier frameworks (Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition, 2014; Lawrence et al., 2015), and has been instrumental in enhancing the conceptual understanding of the linkages between food systems, diets, and nutrition. More distinctively, it elaborates on the role of food environments in facilitating sustainable consumer food choices (Herforth & Ahmed, 2015; Turner et al., 2018) making it a key reference point shaping national and international research and policy (see for example Brouwer et al., 2020; Clapp et al., 2022; Fanzo et al., 2020; Nordhagen et al., 2022; Raza et al., 2020; Research Institute (IFPRI), 2019, 2020). Food systems thinking recognises that actions to curb malnutrition need to engage with the complex interlinkages between processes of food production, distribution, retail, consumption, and the natural, technological, political, social, and economic environments within which they are embedded. These interlinkages are manifested across local, domestic and international levels, driven in part by the processes of globalisation, financialization of food and trade liberalisation, shaping the quality of food available to consumers (Baker et al., 2021; Clapp, 2014; Hawkes, 2006).

By mobilising the 2017 HLPE Sustainable Food Systems Framework for Improved Nutrition, this paper investigates how such framework and language of interdisciplinarity are practised in research on the consumption of “industrial diets” among adolescents in Ghana. In addition, we develop a conceptual framework to illustrate horizontal and vertical linkages across and within food systems domains and levels of analysis emerging out of studies on consumption of industrial diets among adolescents in Ghana. “Domains” are drawn from the 2017 Sustainable Food Systems Framework and refer to the different components and processes through which food is produced, distributed, consumed and disposed of. With the term “levels” we refer to the macro, meso, micro scale of analysis in which the domains are positioned and examined (Tankwanchi, 2018). The section ‘Building an Evidence and Gap Map’ (page 5) provides further explanation and expands the definitions of these terms. Finally, we define “industrial diets” as those characterised by high consumption of purchased ultra-processed foods and beverages (hereafter termed ‘ultra-processed foods’ or ‘UPFs’), that through the addition of sugars, salt, fats, and other edible ingredients are made “more durable, palatable, and easier to handle and therefore help boost sales and reduce costs to processors and retailers’’ (Winson, 2013, pp. 173–174).

Ghana was classified a lower-middle income country (LMIC) in 2011, however, like many other countries of similar status it is characterised by high levels of poverty and growing inequality. The country is also at the tipping point of the nutrition transition. To be specific, food consumption patterns have transformed dramatically through local production and import of processed and UPFs (Andam et al., 2018). Poor nutritional outcomes affect a large proportion of children and adults. Ghana is experiencing a double burden of malnutrition with the simultaneous high prevalence of overweight and anaemia (Development Initiatives, 2021) as well as significant geographical and socio-economic nutrition inequalities within the country. Undernutrition continues to be common among young children (Jonah et al., 2018), but rising levels of overweight and obesity are becoming a key public health issue (Ghana Statistical Service et al., 2015; Ofori-Asenso et al., 2016; Ziraba et al., 2009). Further, diet-related diseases (e.g., diabetes and hypertension) historically common among adults are increasingly being observed in young children and adolescents (Crouch et al., 2022). A recent meta-analysis of over-nutrition estimates found that approximately 19% of children in Ghana are either overweight or obese (Akowuah & Kobia-Acquah, 2020). Among both children and adults, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is reportedly higher among females (Akowuah & Kobia-Acquah, 2020; Ganle et al., 2019; Manyanga et al., 2014), compared to males. Recent studies suggest high prevalence of overweight and obesity is not only a prerogative of urban areas and rates are increasing also in rural areas (Akowuah & Kobia-Acquah, 2020; Asosega et al., 2021; Mbogori et al., 2020; Muthuri et al., 2014; Ofori-Asenso et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, studies point to increased prevalence of both childhood and adulthood overweight and obesity. The heterogeneity of nutritional indicators and experiences with regards to industrial diets’ consumption, make Ghana a relevant example with regards to the transferability of findings and recommendations to other sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) contexts where NCDs were responsible for 37% of deaths in 2019, rising from 24% in 2000 (World Health Organization, 2022). With the exception of South Africa, research on health-harming industries, such as those that produce UPFs, in driving the incidence of diet-related diseases in SSA is fragmented (Reardon et al., 2021). We argue that such gap has policy repercussions. Food policies in many SSA countries tend to focus on food production, leaving a policy gap in relation to global trade, regulations and the role of the food industry in shaping processing, distribution and consumption (Masters et al., 2018a, b).

Adolescents in the LMICs are often at the forefront of dramatic shifts in diets and lifestyles (Aurino et al., 2017). Evidence suggests that adolescent intake of healthy and nutrient-rich foods such as fruit and vegetables is inadequate (Amoateng et al., 2017), and there is high consumption of high-fat, energy-dense, calorie-rich foods (Keats et al., 2018). Crucially, adolescence is an important phase in human development as it represents a transition from childhood to physical, psychological, and social maturity (Hargreaves et al., 2022; Neufeld et al., 2022; Norris et al., 2022). It includes ages 10 to 19 years and is considered a critical window of opportunity to enhance the health of the next generation (Blakemore, 2019; Prentice et al., 2013).

The effects of poor nutritional outcomes have been widely documented. Malnutrition (undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, and overnutrition) has been shown to have adverse negative effects on health and education outcomes in childhood and productivity in adulthood. It also contributes to the vicious cycle of poverty since malnourished children, majority of whom are poor, are more likely to remain malnourished or face other health challenges in adolescence and adulthood, affecting their productivity and participation in the labour market, and contributing to the vicious cycle of poverty (Alderman et al., 2006; Caulfield et al., 2006). Overweight and obesity in both childhood and adulthood increase the risk of non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and some types of cancers (Koplan et al., 2005; Park et al., 2012; Simmonds et al., 2016).

Given these adverse effects, evidence on the drivers of malnutrition is necessary to determine suitable interventions. However, existing evidence from Ghana shows that while there are many studies looking at poor nutritional outcomes and links with diets have focused more on the adult population (see for example Amoateng et al., 2017; Benkeser et al., 2012; Bliznashka et al., 2021; Gyasi et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2015; Obirikorang et al., 2017; Owiredu et al., 2019; Sarfo et al., 2018), and information on the adolescent age group may be limited.

Based on a thorough review of literature from 2010–2022, this paper aims to unpack the extent to which the analysis of recent dietary shifts among adolescents (10–19-year-olds) in Ghana are framed and adequately linked across the various domains and levels of the 2017 HLPE Food Systems Framework. The review maps the evidence and highlights the gaps within studies that have looked at adolescents’ consumption of industrial diets in Ghana, with the aim of addressing the following research questions:

-

What kind of evidence on UPF consumption among adolescents, quantitative and qualitative, exists from community-level or nationally representative household surveys?

-

Which food systems domains and levels of analysis (micro, meso, macro) are included in the reported analysis of adolescents’ diets, and more specifically, on UPFs consumption?

-

Which disciplines and methodologies are mobilised to improve the understanding of the complex interactions between the different domains and levels of the food systems framework that shape UPFs consumption among adolescents?

-

To what extent is the role of the food industry integrated in research on the dynamics around adolescents’ food consumption and nutritional challenges?

2 Methodology

2.1 Literature review methods

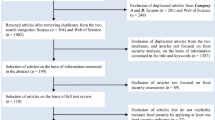

This study followed the guidelines for scoping reviews outlined in the PRISMA-ScR checklist (Tricco et al., 2018) – Fig. 7 in the Appendix.Footnote 1 We searched three main databases between January 2021 and March 2022: Scopus®, Web of Science® and PubMed®, applying the search terms contained in Table 1. The inclusion criteria used to identify studies in the three databases are outlined here:

-

Studies about consumption of UPFs in Ghana. In identifying these foods, we followed the NOVA food classification system that categorises food items based on the processing levels they have undergone (Monteiro et al., 2016).

-

Studies about dietary intake among adolescents. Adolescents were defined as children aged 10–19 years, in line with the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO).Footnote 2

-

Articles published between 2010 and February 2022.

-

Articles published in social sciences (economics, sociology, development studies), public health, nutrition, and agriculture.

We excluded studies from physical and life sciences: engineering, biological sciences, immunology, and biological sciences (including molecular biology), chemistry, mathematics, and machine sciences. In some cases, such as PubMed, we used the following words to exclude articles in the life and physical sciences: biology, bacteria, molecular, biological, biochemical, candida, microbiology, microbial, immunology, bacillus, pollution, chemical, malaria, parasite, sexual, viral, virus, bats, antioxidant, lipid.

Our search initially identified 5615 articles. After excluding duplicates, we screened abstracts of the remaining studies (4568). From these, a further 4543 that did not meet the study’s inclusion criteria were dropped. The remaining 185 articles were read in detail to assess suitability for inclusion. The in-depth assessment process resulted in the exclusion of a further 160 articles because they did not focus on the review’s central theme of processed food consumption among adolescents, although they did cover other food and nutrition security themes such as food production, acquisition, and consumption. In total number, 25 studies were deemed eligible for analysis. The lead author reviewed all 25 articles in full.

This findings from the search show that research on adolescents and industrial diets has developed over recent years with majority of studies (84%) published after 2014 (Fig. 1). The highest number of publications were recorded in 2019, but this was followed by a decrease in 2020 and 2021, potentially due to the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on research activities.

2.1.1 Building an evidence and gap map

To identify themes from the 25 included articles, we applied an Evidence and Gap Map (EAG) lens. More specifically, we drew from the EAG analysis developed by IMMANA (Innovation Methods and Metrics for Agriculture and Nutrition Actions) which summarises the extent and type of research evidence available on food systems and agriculture-nutrition linkages, focusing on tools, metrics, and methods (Sparling et al., 2021). Our analysis focuses on two vectors: i) draws on the sustainable food systems framework domains; and ii) levels of analysis, as outlined in Table 2. The domains draw from the Sustainable Food Systems Framework (Fig. 2) developed by the High-Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE, 2017). The framework outlines: i) the key drivers that affect food availability, access, utilisation, stability, and sustainability including food supply chains, food environments, and consumer behaviours; and ii) the links with diets and effects on health and nutritional outcomes as well as the broader impacts at the social, economic, and environmental level. In addition, our analysis is broken down by the level of analysis into macro, meso, micro, which refer to the scale in which a domain (or multiple domains) is positioned and examined (Tankwanchi, 2018). For example, the macro level domains include agriculture and trade policies and institutions that influence, among others, food and agricultural markets, the set-up of food environments, and food availability. The meso level of analysis pertains to the intermediate level between macro and micro level of analysis, or the interface between them, including specific food sectors, local markets, or agricultural practices policies. Finally, micro level domains represent individual and personal factors such as food acquisition and consumption behaviours and preferences, dietary and nutritional outcomes. We recognise there can be interlinkages between micro-meso-macro scales and that domains are not isolated to a single level of analysis.

In Table 2, the first food system domain relates to the policy environment. This domain is about national and international political and institutional actors, that shape ultra-processed food availability, accessibility, and utilisation. The next set of domains are about the food environment. Our definition of food environment draws from the food systems framework (HLPE, 2017) and Herforth and Ahmed’s definition and measurement (Herforth & Ahmed, 2015). Food environment domains include food availability, food acquisition patterns, physical access to food (convenience), affordability (income and food prices), and desirability which includes promotion, advertising, cultural norms, dietary habits, and consumer knowledge and awareness. We also include a domain to capture consumer behaviour and food consumption, for example decision making on food consumption, where food consumption occurs, and dietary behaviour. The last domain is the nutritional and health outcomes domain. These are outcomes that are directly linked to dietary intake among other factors, which are the culmination of the interaction between the consumer(s) and the food system.

In addition to these dimensions, the review also examined the research methods and metrics applied in each study, including data sources, research location (geographical setting) and target age groups, among others.

3 Findings

3.1 Findings at macro-level

Macro-level themes and analysis was only included in two studies, signalling methodological and conceptual gaps in linking consumption of UPFs among adolescents to macro processes, such as food polices, governance, and food supply. It also signals there is a gap of further systematic research on how policies regulate harmful food items, which measures address unclear labelling and harmful advertising of ultra-processed foods directed at adolescents in Ghana. No studies covered themes relating to food production, processing and distribution, trade policies, and food imports. Only two studies (Adom, De Villiers, et al., 2019; Adom, Kengne, et al., 2019; Pradeilles et al., 2019) covered food policy and governance themes. Adom, De Villiers et al. (2019) and Adom, Kengne et al. (2019) assessed school policies and practises in a study conducted in an urban area of Greater Accra and found that while nearly all schools (six public and six private) had policies and practises on nutrition and healthy eating, these were not associated with decreased likelihood of overweight and abdominal obesity or higher Body Mass Index (BMI) scores. Pradeilles et al. (2019) used key informant interviews with stakeholders in leadership roles in urban areas of Accra and Ho to assess community readiness to implement actions to improve diets of adolescent girls and women of reproductive ages. A community readiness model tool used to assess community awareness of interventions and motivations to implement the programme, showed that both communities were at a “vague awareness stage”, where only a few community members had some information (albeit limited) about local efforts to improve nutrition, community members perceived consumption of unhealthy foods and beverages as a concern but had little motivation to act on this, and availability of resources to mobilise community members towards tackling this issue was limited.

One of the key findings from the macro-level themes is the focus on individuals or community/school. None of the studies examine these themes at the administrative levels of governance (either national or sub-national level – e.g., regions or municipalities).

3.2 Findings at meso-level

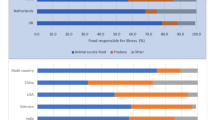

Overall, there is more focus on meso-level research themes compared to macro-level themes (see Fig. 3). Meso-level themes were included in 10 studies and covered food availability and points of sale, desirability (advertising and product placement), and power and influences over decision-making on food consumption. The meso-level themes relate mainly to the food environment: where adolescents acquire ultra-processed foods; the marketing and advertising of these foods; types of foods acquired and food safety issues; and modalities through which the food industry influences acquisition and consumption of UPFs. Surprisingly, we found no studies that examined the cost of UPFs consumed by adolescents.

Our review found that purchased foods constitute a significant fraction of adolescents’ food consumption: between 40 and 86% of those surveyed purchased food (Buxton, 2014; Fernandes et al., 2017). While these purchases constitute both UPFs and non-UPF foods, we found that a substantial share of those surveyed by the studies purchased UPFs. For example, Fernandes et al. (2017) reported that 26% of vendors selling foods to children within the school environments sold confectionary. Buxton (2014) reported that 16.5% of adolescents purchased pastries (e.g., doughnuts, cakes and meat pies), 13.7% purchased ice crem, another 13% acquired soft drinks while 11.7% canned/packaged fruit juice. Nearly three quarters of studies reviewed focused on where adolescents consumed ultra-processed foods (Abiba et al., 2012; Abizari & Ali, 2019; Adom, De Villiers, et al., 2019; Adom, Kengne, et al., 2019; Buxton, 2014; Darling et al., 2020; Fernandes et al., 2017; Ganle et al., 2019; Ogum-Alangea et al., 2020; Stevano et al., 2020a, b). These studies show that the main acquisition points include school vendors operating within and outside schools, canteens, fast food outlets, and supermarkets (Adom, De Villiers, et al., 2019; Adom, Kengne, et al., 2019; Fernandes et al., 2017; Ogum-Alangea et al., 2020; Pradeilles et al., 2021; Stevano et al., 2020a, b) These findings indicate the extent of the proliferation of ultra-processed food within school environments, including through informal channels (such as vendors operating within school proximity).

There are variations in acquisition points and types of foods available in public and private schools, with some of the latter having improved enforcement of who and what could populate the school food environment. For example, Ogum-Alangea et al. (2020) found that, whereas there were 77 food vendors within 100-m radius of five schools (both public and private) included in their study, the vendors were disproportionately located around public schools. Additionally, while in public schools there were hawkers who sold UPFs such as confectioneries, private schools did not have any hawkers within the school environment but had canteens and snack bars instead. Similarly, Stevano et al. (2020b) found that food vendors were not allowed to operate inside private schools, while public schools did not have canteens and food vendors were free to operate within and outside the schools. They also show that in private schools, canteens sold monthly menus selected in advance by children (8–11 years) or their families, something that was not observed in public schools. Adom, De Villiers et al. (2019) and Adom, Kengne et al. (2019) found that private schools were more likely to have school cafeterias and school shops compared to public schools; 74% of private schools had a cafeteria, compared to 26% of public schools. These studies show that differentials in socio-economic status of adolescents (proxied by the types of school they attend) are likely contributors to the differences in dietary behaviours and access to UPFs.

Supermarkets did not emerge as a key UPF acquisition point, despite being considered a key distributor of these items. Only one study (Stevano et al., 2020a) examined the role of supermarkets in adolescent food consumption. They found that together with school canteens, supermarkets were the main sources of UPFs for adolescents from high socio-economic status, while those from low-income households mainly sourced these foods from street vendors.

While several studies focused on where adolescents acquired food, much fewer focused on the types of industrial foods available at purchase points. However, those that studied this found that foods sold to adolescents include ultra-processed food items such as confectioneries, soft and carbonated drinks, packaged fruit juices, biscuits, friend pastries, packaged snacks, chocolates, sweets/toffees, chips & crackers, popcorn, and ice creams (Fernandes et al., 2017; Ogum-Alangea et al., 2020). Healthier options such as eggs, cooked meals, fruits, and vegetables were also available within school environments (Fernandes et al., 2017; Ogum-Alangea et al., 2020). Some studies suggest that there are some differences in types of food items available across private and public schools. Adom, De Villiers et al. (2019) and Adom, Kengne et al. (2019) examined types of foods at cafeterias, shops, and restaurants within one kilometre radius of schools and found that compared to those in public schools, children (8–11 years) in private schools had significantly more access to both healthful (e.g., raw fruits and vegetable salads, cooked meals and 100% fresh fruit juice) and unhealthy foods (e.g., chocolates; sweets/toffees; sodas/soft drinks; packaged fruit juices; cakes, cookies). This finding potentially explains why they also found that those attending private schools had higher BMIs and were at increased likelihood of abdominal obesity and overweight, because they had more access to ultra-processed foods.

Food safety, a key concern for Ghana, emerged in three studies (Pradeilles et al., 2019, 2021; Stevano et al., 2020a), all of which showed that hygiene and food safety affected consumer choices on food acquisition points.

In this review, we found a few studies that focused on food advertising and product placement among adolescents. These studies show that ultra-processed food items are advertised through billboards(Abiba et al., 2012; Bragg et al., 2017; Holdsworth et al., 2020; Stevano et al., 2020a), small signs or displays at front of stores or at storage units (Bragg et al., 2017). Ultra-processed food product constitutes most of the food adverts. In Ghana, the most advertised food products are sugar-sweetened beverages, followed by milk-based sweet drinks targeted at adolescents and other child age groups (such as Nestle’s Milo) and Indomie noodles (Bragg et al., 2017; Stevano et al., 2020a). An analysis of 77 photos of outdoor non-alcoholic beverage adverts taken in the Accra area found that over 70% of the adverts were on sugar-sweetened beverages, mainly Coca Cola products (Bragg et al., 2017).

UPFs advertisements and marketing are increasingly targeted at children (including adolescents), partly because they are attentive to food adverts and can recall which food items are commonly advertised and explain why specific adverts attract their attention (Stevano et al., 2020a). To effectively target adolescents and other child age groups, these advertisements are placed within the vicinity of school environments (Bragg et al., 2017; Stevano et al., 2020a), feature children (including adolescents) (Bragg et al., 2017), and use miniature packaging that is attractive and cost-friendly (Stevano et al., 2020a).

A key issue that relates to food advertising is the influence of food industry in adolescents’ decision-making process about food acquisition and consumption. This is a sparsely researched area, as we found only one study that examined this (Stevano et al., 2020a). The findings show that, contrary to existing literature showing supermarkets as a key contributor to the nutrition transition in many LMICs, this is not necessarily the case in Ghana. Instead, in Ghana, the food industry’s influence on adolescent food consumption (especially those from poorer socio-economic backgrounds) is occurring through the informal food sector, where street vendors and other traders positioned within school environment sell packaged foods to children (including adolescents). This finding shows proliferation of the ultra-processed food industry through a complex interaction between the formal and informal ultra-processed foods sector.

3.3 Findings at micro-level

Micro-level themes were the most popular/dominant across studies. We found that only one study did not contain any of the micro-level research themes such as food acquisition, physical and economic access to food, and dietary habits and food intake.

Within the micro-level themes analysed, food affordability, which is related to the personal domain of food environments, was covered by most studies (Fig. 4). Several studies examined socio-economic status of households as measured by income or wealth indices and explored links with food consumption and nutritional outcomes (Abizari & Ali, 2019; Adom, De Villiers, et al., 2019; Adom, Kengne, et al., 2019; Aryeetey et al., 2017; Fernandes et al., 2017; Holdsworth et al., 2020; Ogum Alangea et al., 2018; Stevano et al., 2020a, b). In most cases, however, wealth indices were the main measure of socio-economic status possibly due to difficulties in collecting data on household income from adolescents.

Some studies looked at access to pocket money and potential links with dietary behaviours and the types of food items purchased, including UPFs like soft drinks (Abizari & Ali, 2019; Buxton, 2014; Fernandes et al., 2017; Stevano et al., 2020a, b). Fernandes et al. (2017) found that adolescents (10–17-year-olds) were more likely than children aged 5–9 years to bring money to school for food purchases and less likely to consume breakfast or lunch at home. Ultra-processed foods are popular purchase options for adolescents. Abizari and Ali (2019) found that compared to those without, adolescents with pocket money were 4.7 times more likely to have a sweet tooth pattern, a dietary pattern derived through principal component analysis, and which was characterised by intake of: tea and coffee, milk and milk products sugar sweetened snacks, sweets (chewing gums and toffees), energy and soft drinks, and fats and high fat-based foods. Buxton (2014) found that 41.7% of adolescents who purchased food at school bought cooked meals such as fried rice and fried chicken, 16.5% purchased pastries (cake, meat pie, sausage roll, doughnut), 13.7% purchased ice cream (FanYogo or Fan chocolate),Footnote 3 13.0% purchased soft drinks (Fanta, coke, sprite), 11.7% canned/packaged fruit juice while only 3.4% purchased fruit.

Another key aspect of the food environment’s personal domain is physical accessibility (convenience), examined in only four studies (Fernandes et al., 2017; Pradeilles et al., 2019; Stevano et al., 2020a). The focus in these studies is on the distance that adolescents and other children travel to and from school and how this impacts the foods they have access to and what they consume. The studies indicate distance from school is a negative factor in healthy consumption behaviour, and those who travel far to school are less likely to consume breakfast. They tend to purchase their foods from street hawkers or vendors within the vicinity of their schools. For example, Stevano et al. (2020a) found that adolescents from lower socio-economic status were more likely not to consume breakfast at home, compared to those from the high-income households, partly due to time and distance they have travel to and from school, as well as the mode of transportation (walking or use of public transport). In comparison, they found that a large percentage of adolescents who consumed breakfast were from higher socio-economic backgrounds and were driven to schools. Similarly, another study (Adom, De Villiers, et al., 2019; Adom, Kengne, et al., 2019) that compared breakfast consumption among 8–11-year-olds (n = 543) in private and public schools found out that the proportion of those in private schools reporting breakfast consumption was significantly higher than those in public schools (78.3% vs 65.7%). Again, this is likely linked to distance travelled and transportation mode.

Nearly all studies (23) addressed the food consumption domain of dietary patterns and behaviours (Abiba et al., 2012; Abizari & Ali, 2019; Adom, De Villiers, et al., 2019; Adom, Kengne, et al., 2019; Appiah et al., 2021; Aryeetey et al., 2017; Buxton, 2014; Darling et al., 2020; Fernandes et al., 2017; Ganle et al., 2019; Holdsworth et al., 2020; Intiful & Lartey, 2014; Ogum Alangea et al., 2018; Ogum-Alangea et al., 2020; Oyekale, 2019; Pradeilles et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2017; Sadik, 2010; Sirikyi et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2021; Stevano et al., 2020a, b; Yang et al., 2017). A breakdown of the food consumption domain shows that the most popular category was dietary intake which was included in all the studies except Fernandes et al. (2017) where focus was on dietary habits (e.g., breakfast consumption, packed meals vs spending at or near school).

Under dietary patterns, breakfast consumption/skipping emerged as an area of interest in some studies, potentially due to the reported positive effects of breakfast consumption on cognitive performance, moods, and nutritional outcomes. A key part of the analysis is the relationship between consuming breakfast at home and consuming purchased food before/on the way to school and whether there are age and socio-economic factors shaping these patterns. A study set in the rural areas of the country found that breakfast consumption at home was reported by 87.6% of children (aged 5–16 years) and mainly consisted of traditional cereal-based meals (Ganle et al., 2019). However, breakfast consumption at home appears to be less common in urban areas of the country. One such study of 820 adolescents in the more urbanised Cape Coast metropolis (Buxton, 2014), found that nearly two thirds (62.8%) of the adolescents did not consume breakfast at home but purchased food during commute to school using pocket money provided by their parents. Adolescents also reported their preference for bought food over home-prepared meals. Stevano et al. (2020a) found that adolescents from lower socio-economic status were more likely not to consume breakfast at home, compared to those from the high-income households, because of the long distances they travelled to school which required them to leave home early to make it to school on time. Another interesting finding that compared younger children (5–10 years) to adolescents found they are less likely to have breakfast or lunch at home and are more likely to bring money to school to buy food (Fernandes et al., 2017).

Our review found that decision-making around adolescents’ food consumption is made by a wide range of actors, depending on where and when food is acquired and/or consumed. Buxton (2014) found that over half (54.6%) of adolescents surveyed reportedly made independent decisions about their food purchases within the school environment, 26.3% reported their parents made the decision, 10% were influenced by classmates, while 10% were influenced by siblings or friends. Similarly, through focus group discussions, Stevano et al. (2020a) found adolescents made decisions about food acquisition and consumption mainly in relation to their snacks and foods bought and consumed at school. They found that decisions about meals prepared and consumed at home, e.g., supper were made by parents, often the mother. While adolescents often helped with food acquisition and preparation, they were guided by their parents. Sometimes decisions about foods consumed at home were made by adolescents when their parents or caregivers were away; in these cases, some of the adolescents mentioned consuming packaged foods, such as Nestle’s Milo, instead of home cooked full meals.

Studies that focused on dietary intake mainly applied recall methods to inquire about the types and frequencies of foods consumed. In the appendix, we have provided tables showing frequencies of occurrence of foods (see Table 6) and the type of food(s) decovered in each study (see Table 8). Some studies focused on just one or two food items, while others included a range of ultra-processed food items. The most popular ultra-processed food items included in nearly all studies were sugar-sweetened beverages such as carbonated/soft drinks and fruits juices. Studies found a high level of consumption of carbonated soft drinks among 12–15 adolescents, approximately between 54 and 72% (Smith et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017). However, data on urban-rural breakdown is not available. Consumption of energy and carbonated drinks (23% and 30% respectively) was also high among pregnant adolescent girls (12–19) and reached 71% among the older age groups (16–19) (Appiah et al., 2021).Footnote 4 Studies that focused on the links between consumption of soft drinks and gender did not find a significant association (Darling et al., 2020).

Nearly half of studies reviewed collected data on nutritional and health outcomes. No studies covered diabetes incidence or prevalence in adolescents, presumably because the condition is more prevalent among older demographic groups. Table 3 shows that the studies that looked at nutritional outcomes find high and varying levels of overweight and obesity, partly due to the differences in characteristics of geographical settings, sample sizes, age groups included in the studies, and standards used to derive anthropometric indices. Overall, the studies show that prevalence is higher among females than males, and among those attending private schools compared to those in public schools.

Some studies examined the links between nutritional outcomes and consumption of ultra-processed food items. For example, one study (Ogum Alangea et al., 2018) found that an energy dense dietary pattern, which consisted of a typically “westernised diet”,Footnote 5 was positively and significantly associated with child overweight status. Another (Ganle et al., 2019) found that children (5–16 year-olds) who consumed fizzy drinks on most days had statistically significant increased odds of being obese compared to children who hardly or did not consume any fizzy drinks at all. Another study (Sirikyi et al., 2021) found that ice cream intake was predictive of overweight/obesity but did not find significant association between fast food intake and sweetened beverages intake and BMI categories.

3.4 Vertical and horizontal food systems linkages

We now examine the extent to which the various domains and levels of analysis classified in this study on ultra-processed food consumption among adolescents in Ghana are connected. We assess both the horizontal linkages (i.e., connections made within the same level of analysis) and vertical linkages (i.e., connections across different levels of analysis). Firstly, we describe how the papers we have reviewed conceptualise the food systems domains and depict (Fig. 5) the linkage between the macro-meso-micro levels of analysis that shape consumption of unhealthy foods among adolescents in Ghana. Detailed information on how many studies connect different domains at different level of analysis can be found in the appendix (see Table 5). Secondly, we conduct a correlation analysis of the food systems domains represented in the papers (Fig. 6).

At the macro level, only the domain of food and nutrition policy in relation to adolescents’ UPF consumption was being considered. Other domains such as trade policies, food governance and food supply were not included in the analyses retrieved in this review. With regards to macro-meso vertical linkages, food and nutrition policies were connected to the domain of UPFs availability and food safety. Surprisingly, the macro domain of food and nutrition policies were not linked with the meso domains of food industry influences nor with food advertising and marketing practices. In terms of horizontal linkages, within the meso scale of analysis, food advertising and marketing were considered within the sphere of influence of the food industry. In turn, together with UPF availability, these domains shape what products are available and how they are placed in school food environments and among local retailers, where, especially among poorer socio-economic contexts, operate via informal channels. The vertical linkages that were most common in the scoping review were the meso-micro ones, with virtually all domains being connected in the analyses. Within the micro scale of analysis, horizontal linkages were made between adolescents’ socio-economic status and the physical accessibility (especially in terms of convenience and time) to points of consumption or healthy or unhealthy dietary practices (i.e., skipping breakfast or not having breakfast at home). Together with the domains of personal decision-making power and food knowledge and awareness, they these micro-level domains shape food consumption. Finally, nutritional and health outcomes among the most studies micro-domains, which are assessed in relation to food consumption.

Figure 6 depicts a heatmap illustrating the correlation between different food systems domains and analysis levels. Additional information showing the values of the correlation coefficients is available in the appendix (see Table 7). Correlation heat maps are a two-dimensional plot depicting the degree of correlation between variables represented by colours. Correlation ranges from -1 to +1. The diagonals are all orange because each variable is correlated to itself (correlation coefficient = 1). The areas in dark blue on the other hand denote 0 to -1 correlation (meaning, that the two food systems domains are not positively associated to each other). The other colours in between, denote different degrees of correlation. Domains are in turn classified as covering aspects linked to the food systems at the macro, meso and micro levels.

The figure shows an overall low correlation across the different levels of analysis (macro, meso and micro). This means that there is a tendency for research on ultra-processed food consumption among adolescents in Ghana to adopt a clustered analysis approach, where different food systems domains within the same level of analysis are jointly studied. For example, convenience, a meso domain which includes time or distance travelled to food sources, and modes of transport, tends to be associated with the analysis of food supply. Correlation between 0.6 and 0.4 is found between convenience and food source, and between food consumption and place of consumption. However, there are some exceptions. Some domains, although they belong to different levels of analysis, present correlation coefficients between 0.8 and 0.6, meaning that there is a high tendency to observe the analysis of a given domain in combination with another one. An example is food policies and food supply which belong to the macro and meso levels respectively, and which have a correlation of 0.7. Very low correlation levels were found between food policy and governance and economic access (related to socio-economic aspects that shape access to food), and health and nutritional outcomes. This last domain tends to be analysed either individually or in conjunction with the food consumption domain only. Interestingly, we found that the analysis of power (that in this paper includes food industry influence, e.g., through use of formal/informal channels and school programmes as well as food choices autonomy) was not related to the food policy and governance domain nor health and nutritional outcomes.

3.5 Tools, methods, metrics and geographies commonly adopted in analysing adolescents’ diets

Majority of studies (84%, n = 21) used quantitative methods, while only seven used qualitative methods (Table 4). Majority of studies (57%) were cross-sectional studies. We did not identify any panel (longitudinal) studies on adolescents’ dietary patterns and outcomes and their associated factors over time. Overall, primary research was the main source of data, used by 22 out of 25 of research articles. All studies that employed qualitative and mixed methods were based on primary research. Similarly, most of the quantitative methods research (82%) used primary sources of data, although a few articles (n = 3) used secondary data. Overall, only three studies made use of secondary data (Oyekale, 2019; Smith et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017). Two of the studies (Smith et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017) both used data from the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS), a school-based surveillance survey led by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and United States CDC. The other, (Oyekale, 2019), used data from the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey.

Studies that applied quantitative methods mainly used structured questionnaires to collect data on socio-demographic characteristics (see Appendix, Table 8). For studies that collected dietary intake data, the main data collection instruments used were food frequency questionnaires, with either 24-h or 7-day recall periods. Some studies used longer recall periods. For example, Abiba et al. (2012) applied a two-week recall period, while Darling et al. (2020) used a 30-day recall and Ross et al. (2017) used a 6-month recall period. These recall periods are particularly lengthy for adolescents, especially in cases where they are asked about quantities consumed and frequency of consumption within and outside the home. Additionally, while most studies on dietary intake collected data directly from adolescents or other child age groups where applicable, one study (Fernandes et al., 2017) collected the data from caregivers. Studies should include robust, piloted and age adequate protocols and methods and training to collect food consumption data from adolescents to reduce the risk of recall bias and ensure accurateness of the data. The number of food items included in food consumption studies varied significantly. One study used a checklist of 229 food items (Holdsworth et al., 2020), another 60 food items (Abizari & Ali, 2019), another 100 food items (Ogum Alangea et al., 2018) while those based on GSHS data focused only on carbonated soft drinks (Smith et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017).

The sample sizes used in the studies vary. In one case, a study that looked at food consumption in orphanages included only 40 participants purposively sampled (Sadik, 2010), while another study included all first-year students (196) who reported for medical test at a university in the Cape Coast region (Sirikyi et al., 2021). Other studies had much larger sample sizes. An example is a mixed-methods study (Fernandes et al., 2017) which examined children’s food purchases. This study surveyed 4285 children (aged 5–17 years) in 111 schools sampled from 60 districts from the 10 regions of Ghana. However, the study covered only urban and peri-urban areas of the country. Majority of the studies do not have nationally representative samples, and those that do use secondary sources of data such as the Ghana Demographic and Health surveys (Oyekale, 2019).

In terms of geographical focus, most studies were carried out in urban areas, with some popular locations including Accra, Cape Coast, and Tamale metropolitan areas. More precisely, seven studies were conducted in Accra, five in the greater Accra regions (Ga East and Adentan municipalities) while four studies were conducted in the Cape Cost and three in Tamale. Only two studies (Darling et al., 2020; Intiful & Lartey, 2014) were conducted in rural areas alone (Manya Krobo in Eastern region and Ningo Pram-pram in Greater Accra respectively). Three studies (Bragg et al., 2017; Oyekale, 2019; Yang et al., 2017) covered both urban and rural locations (Accra & Cape Coast in Bragg et al. (Bragg et al., 2017) and national samples for both Yang & Oyekale (Oyekale, 2019; Yang et al., 2017). The large number of studies focusing on urban areas is not surprising given the higher (reported) consumption of ultra-processed foods in urban locations, compared to rural settings, in many countries in the Global South.

Nearly all studies (24) included the individual (adolescent) as the unit of measurement. Four studies used a school environment (Adom, De Villiers, et al., 2019; Adom, Kengne, et al., 2019; Fernandes et al., 2017; Ogum-Alangea et al., 2020) as the unit of measurement, while one study used outdoor spaces, including a national highway, as the unit of analysis (Bragg et al., 2017). We found that only one study conducted a mapping exercise on obesogenic environments in residential areas (Holdsworth et al., 2020). We found that in most of the studies (64%), data collection was conducted from within school environments, while in eight it was done at household residence. Majority of the studies do not exclusively cover adolescents but include them as part of a broader age group. There were 17 studies that included at least one other age group in addition to adolescents. The most common additional age group was 5–9-year-olds (Abiba et al., 2012; Adom, De Villiers, et al., 2019; Adom, Kengne, et al., 2019; Fernandes et al., 2017; Ganle et al., 2019; Intiful & Lartey, 2014; Ogum-Alangea et al., 2020). Some studies focused exclusively on the adolescent age group and did not include any other demographic age group (Abizari & Ali, 2019; Aryeetey et al., 2017; Buxton, 2014; Darling et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017). Nearly all studies included both male and female adolescents, and only three focused on female adolescents only (Oyekale, 2019; Pradeilles et al., 2019; Ross et al., 2017). Only one study (Bragg et al., 2017) did not have information on gender as the community was the measurement unit.

More than half of these studies (56%) compared public and private schools in respect to food environments, dietary patterns, and adolescents’ nutritional outcomes. However, a few studies that focused on schools did not specify whether the schools were public or private (Abiba et al., 2012; Abizari & Ali, 2019) while two studies focused only public schools (Fernandes et al., 2017; Intiful & Lartey, 2014).

4 Discussion

The findings show that there are key gaps in food systems research in Ghana. Firstly, we find that, methodologically, there is a quantitative bias and absence of qualitative research that provide deeper understanding of the factors underlying consumption of industrial diets among adolescents. Second, studies have mainly focused on urban areas. Third, not all aspects of food systems domains are covered equally. The macro-level themes, such as food policies and food supply, are least studied. Importantly, when it comes to adolescents’ dietary patterns and nutritional outcomes, in the context of changing food environments research and practice, the literature tends to focus on the individual domain (i.e., links between food consumption and nutritional outcomes), and remains disconnected with the whole complexity of the food systems framework. In particular, the activities, and repercussions of the food industry on adolescents’ food choices and practices are neglected. Future studies should focus on these under-studied domains of food systems and examine linkages between macro, meso, and micro levels of analysis. More focus should also be paid to qualitative and/or mixed methods approaches to enhance interdisciplinarity in this area of research. Finally, more attention should be given to neglected geographical settings, i.e., such as peri-urban and rural areas and the contextual marketing processes through which ultra-processed foods penetrate even the most remote food environments (i.e., via informal channels).

In recent years research and practice on nutrition has adopted the language and practice of interdisciplinarity and systems thinking. Distinctively, the HLPE report on Sustainable Food Systems Framework for Improved Nutrition (HLPE, 2017) identifies the functions of and interactions between food supply chains, food environments, and consumer behaviour as entry and exit points for nutrition and health outcomes. It recognises that the challenge to ending malnutrition is a complex and multi-layered endeavour that requires strategies to reverse the current paradigms of food production and distribution that rely on supplying overabundant energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods and damaging the environment. To meet these challenges research and practice should therefore adopt: 1) a multi-scalar approach, i.e., interlocking and relating different aggregation levels, from the individual to the global, passing through the household, community, national and global level; 2) practice interdisciplinarity that improves the understanding of complex problems, instead of studying them from a single discipline perspective. Whilst these connections are theoretically outlined, in practice, there is an operational and empirical gap in articulating the response mechanisms between the micro level factors at the “inner core” of these frameworks (e.g., food consumption, nutritional and health outcomes) and meso (e.g., local food markets) and macro level factors (e.g., food policy and governance, and regional and global trade).

For example, in this scoping review no study covered themes relating to trade policies, which is a key research gap considering the role that trade liberalisation has played in globalisation of diets and increased availability of ultra-processed and unhealthy foods available to adolescents in the Ghanaian markets (Hawkes, 2006; Hawkes et al., 2012). We also find that where studies have examined food policies, they were few and only covered individuals or school environments. We found no studies that delved into how food policies at national or sub-national levels, where they exist, apply to the adolescent age group. For example, a key gap is the absence of research linking adolescent’s unhealthy-food consumption and nutrition with food regulation, necessary to ensure domestic and imported food products are safe, sanitary, nutritious, wholesome, and properly labelled.

When it comes to adolescents’ exposure to unhealthy diets, the policy environment is one of the most under-researched domains. There are existing policies in Ghana that speak to various aspects of food security; a recent policy review found 23 policy documents that either mention or are centred on food and nutrition security, from poverty reduction and economic development, to agriculture, nutrition and health, spatial demographic development, climate change, and trade (Linderhof et al., 2019). Examples include Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (Ministry of Food & Agriculture, 2007), and Support to the Planting for Food and Jobs Campaign (FAO, 2020). As is evident, many of these policies are about food production. The National Policy for the Prevention and Control of NCDs in Ghana, published in 2012, focuses on non-communicable diseases and lays out measures to reduce the incidence of NCDs and exposure to risk factors (Ministry of Health, 2012). The policy speaks to the role of unhealthy diets in driving the prevalence of NCDs and suggest control measures like regulating advertising and introducing price controls to discourage consumption of unhealthy foods. The policy mentions intent to discourage sale of unhealthy foods, such as fizzy drinks, in school canteens and compounds and replace them with healthier alternatives such as fruit. More recently, the government published an updated policy on NCDs (Ministry of Health, 2022). The policy focuses on the need for prevention and management of NCDs at primary, secondary and tertiary levels through nutrition interventions, among others. The policy emphasises the need to strengthen the legal regime to prevent NCDs including through regulation of labelling, advertising, and sale of UPFs such as sugar sweetened beverages. Laar et al. (2020) argue that the existence of such policies demonstrates recognition by the government and indicates some level of political will to improve food environments. However, the key challenge remains lack of implementation which hinders progress towards realising local and global targets (Laar et al., 2020). Another key gap is the unavailability of data on government fiscal allocations towards nutrition and health interventions to support access and utilisation of healthier foods by adolescents.

At the meso-level, we find that advertising through television or print and digital media did not emerge as a key research theme in any of the studies. Some studies examined the extent of television viewing and explored links with sedentary lifestyles, but we did not find any studies that linked food advertising on television to adolescents’ dietary intake.

Power features at two levels of analysis: 1) at the meso-level, were power is examined in the context of practices of the ultra-processed food industry to shape consumption of less healthy foods; and 2) at the micro-level, in terms of decision-making power on foods that are consumed by adolescents. These two conceptualizations of power have overlapping features and are interdependent, and research in this area is still sparse. We identify two other missing pieces in the analysis of power in this context: a) how national food regulation (and its absence) shapes the operation of unhealthy food industries and their impact on adolescents’ nutrition; and b) how neoliberal policies account in part for some recent trends in the diets of adolescent population (i.e., foreign direct investment and global food marketing strategies). Specific dietary outcomes reflect context-specific socioeconomic and cultural features in which these policies are operating (Hawkes, 2006).

Unsurprisingly, a major gap identified by this review is the disregard of the food industry’s operations in the research on adolescents’ nutrition in Ghana. Despite their growing influence, food industry practices are discussed only rarely and research on the impacts of industrial food production on nutrition in the SSA is nascent (Nestle, 2013; Popkin, 2014). Food industries remain a neglected and disconnected sector in the understanding of food systems and nutrition interaction in SSA (Reardon et al., 2021), where interventions to lower consumption of UPFs are typically limited to education and information campaigns (Monteiro et al., 2013) and agricultural policies, especially in the African context, targets production (Masters, Bai, et al., 2018; Masters, Rosenblum, et al., 2018).

Our study demonstrates research in this area among Ghanaian adolescents prioritises analysis that covers individual aspects related to food consumption and dietary patterns and behaviours, and health and nutritional outcomes. In doing so, the transformations of food systems and their impacts are predominantly studied at the micro level and focus on the lower right areas of the food systems framework. This is in line with viewing food and diets as medicalised and individualised issues, that require behavioural change, personalised solutions and individual economic incentives (Scrinis, 2016). The joint expansion of medical science and the food industry over the past century have produced the conditions in which eating and feeding are transformed from practices embedded in social, political and economic relations into explicit medical practices (Mayes, 2014). In doing so,”solutions” and interventions put forward, especially in the SSA context, are disconnected with the political economy and contextual specificities of malnutrition (Sathyamala, 2016).

One of the main observations that emerged during our review is that existing research on food consumption focuses on a small number of processed food items. The most popular items being fizzy and sweetened drinks, and fried pastries, perhaps due to their popularity among adolescents. We did encounter many studies that discussed food consumption, but they mainly used broad groups to examine dietary diversity and micronutrient composition, and mainly focused on preschool children and/or pregnant women (Ayensu et al., 2020; Bimpong et al., 2020). We suspect that this is partly due to the challenges of collection of dietary intake data: 1) the high cost of administering food consumption surveys and 2) the impact of long recall periods on accuracy of the data. Lack of detailed data on adolescent’s dietary intake inhibits a comprehensive understanding of the state of ultra-processed food consumption among adolescents and the underlying drivers including across geographical locations (urban/rural) and socio-economic levels.

An additional finding that emerged from our analysis is the limited focus on ultra-processed food consumption among adolescents living in peri-urban and rural areas of Ghana. This is a key research question that needs further exploration given the strong linkages between urban and rural areas and as rural locations become increasingly urbanised. Increased advertising and growing availability in rural contexts have also likely contributed to increased demand for these foods.

Some studies show that increased demand for processed foods may be due to lower cost, compared to healthier alternatives, in addition to other factors like taste and convenience. We were unable to establish if this is the case in adolescents’ dietary intake in Ghana as we found no study that examined food prices of ultra-processed foods consumed by them. There are some studies that have collected general food price data in Ghana (Masters, Bai, et al., 2018; Masters, Rosenblum, et al., 2018; Minot & Dewina, 2015), but they do not necessarily focus on UPFs, particularly those consumed by adolescents within their environments (home or school). It is possible that the administrative costs of collecting food price data may be contributing to this. This is a key research gap that needs further exploration. A related issue is that we did not find any studies that linked supermarket purchases to adolescent processed food consumption despite interest in the supermarket revolution in the Global South. In Ghana, research indicates that there has been a gradual increase in household food purchases from supermarkets (Meng et al., 2014). The studies we encountered on food purchases in supermarkets focus on purchases by other demographic groups or the understanding of food labels and composition and not necessarily in respect to processed foods or adolescents (Aryeetey & Tay, 2015; Darkwa, 2014; Owureku-Asare et al., 2017).

5 Conclusion

This scoping review unpacks the disconnects present in food systems research by mapping the evidence and identifying the gaps within research undertaken on consumption of ultra-processed foods among adolescents in Ghana. More specifically, we focused on which food systems domains are more dominant, paying attention to which levels of food systems analysis (micro, meso, or macro) is more prevalent.

Our study is inclined to suggest that there is still the tendency to address consumption of unhealthy diets among adolescents in a siloed manner and that the analysis tends to fail to join the dots across the food systems framework. We also found that methodologically, there is a quantitative bias in this area of research. Despite the increasingly recognised need to systemically address harmful food consumption across the different food systems domains, research tends to remain focused on the micro actors and factors shaping food production, distribution, consumption, and waste. While the food systems approach has helped drive research and practice towards a more interdisciplinary and multi-scalar space, there are no clear guidelines to operationalise these very needed approaches. Putting in practice food systems thinking requires a deeper engagement with disciplines and methods that tend to be neglected in this area. They include mixed methods and participatory practices coupled with political economy analysis that places the politics of food at the heart of nutritional outcomes (Béné, 2022; Walls et al., 2021).

Our research showed blind spots in food systems research in Ghana and that not all food systems/environment domains are covered equally. This is particularly stark when it comes to the proliferation of unhealthy diets among adolescents, which highlights the depth of the micro–macro gap in this area of study and absence of the role of the food industry in shaping food acquisition. The disconnects within food systems research are manifested in policy. In the Ghanaian context food policy to tackle malnutrition tends to operate from a lens of food security and food production. Only recently has there been a growing recognition of the need to promote policies that take an integrated food environments approach, where food industries are playing a central role. But financial resources and political will are lagging. This is particularly problematic when it comes to adolescents' dietary patterns. The focus of research primarily on micro and individual level nutritional and health outcomes, produces policies that treat unhealthy food consumption patterns as an individual issue that requires interventions to discourage the individual consumption of unhealthy foods. With regards to adolescents, the cross-sectoral cooperation and coordination between agri-food sector, health and education is crucial to promote healthy and sustainable diets. Policy design and research should recognise that national and local food systems are positioned within global political economy processes that shape food environments, food access, tastes, and aspirations in multiple ways (Fig. 7).

Data availability

The data in this paper derives from secondary material available to all.

Notes

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses—Extension for Scoping Reviews.

Flavoured ice cream tubs.

The westernized diet included: sugar-sweetened beverages, fried foods, processed meats, spreads and toppings, fruits and fruits juices, cocoa beverages and dairy products, and high calorie snacks.

References

Abiba, A., Grace, A., & Kubreziga, C. (2012). Dietary patterns on the nutritional status of upper primary school children in Tamale metropolis. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 11(7), 689–707. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjn.2012.689.707

Abizari, A. R., & Ali, Z. (2019). Dietary patterns and associated factors of schooling Ghanaian adolescents. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 38(1), 5–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-019-0162-8

Adom, T., De Villiers, A., Puoane, T., & Kengne, A. P. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of overweight and obesity among school children in an urban district in Ghana. BMC Obesity, 6(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-019-0234-8

Adom, T., Kengne, A. P., De Villiers, A., & Puoane, T. (2019). Association between school-level attributes and weight status of Ghanaian primary school children. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6937-4

Akowuah, P. K., & Kobia-Acquah, E. (2020). Childhood obesity and overweight in Ghana: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2020, 1907416. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1907416

Alderman, H., Hoddinott, J., & Kinsey, B. (2006). Long term consequences of early childhood malnutrition. Oxford Economic Papers, 58(3), 450–474. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpl008

Amoateng, A. Y., Doegah, P. T., & Udomboso, C. (2017). Socio-demographic factors associated with dietary behaviour among young Ghanaians aged 15–34 years. Journal of Biosocial Science, 49(2), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932016000456

Andam, K. S., Tschirley, D., Asante, S. B., Al-Hassan, R. M., & Diao, X. (2018). The transformation of urban food systems in Ghana: Findings from inventories of processed products. Outlook on Agriculture. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030727018785918

Appiah, P. K., Naa Korklu, A. R., Bonchel, D. A., Fenu, G. A., & Wadga-Mieza Yankey, F. (2021). Nutritional knowledge and dietary intake habits among pregnant adolescents attending antenatal care clinics in urban community in Ghana. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8835704

Aryeetey, R., & Tay, M. (2015). Compliance audit of processed complementary foods in urban Ghana. Frontiers in Public Health, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00243

Aryeetey, R., Lartey, A., Marquis, G. S., Nti, H., Colecraft, E., & Brown, P. (2017). Prevalence and predictors of overweight and obesity among school-aged children in urban Ghana. BMC Obesity, 4(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-017-0174-0

Asosega, K. A., Adebanji, A. O., & Abdul, I. W. (2021). Spatial analysis of the prevalence of obesity and overweight among women in Ghana. BMJ Open, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041659

Aurino, E., Fernandes, M., & Penny, M. E. (2017). The nutrition transition and adolescents’ diets in low- and middle-income countries: A cross-cohort comparison. Public Health Nutrition, 20(1), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016001865

Ayensu, J., Annan, R., Lutterodt, H., Edusei, A., & Peng, L. S. (2020). Prevalence of anaemia and low intake of dietary nutrients in pregnant women living in rural and urban areas in the Ashanti region of Ghana. PLoS ONE, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226026

Baker, P., Lacy-Nichols, J., Williams, O., & Labonté, R. (2021). The political economy of healthy and sustainable food systems: An introduction to a special issue. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10(10 Special Issue on Political Economy of Food Systems), 734–744. https://doi.org/10.34172/IJHPM.2021.156

Béné, C. (2022). Why the great food transformation may not happen – A deep-dive into our food systems’ political economy, controversies and politics of evidence. World Development, 154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105881

Benkeser, R. M., Biritwum, R., & Hill, A. G. (2012). Prevalence of overweight and obesity and perception of healthy and desirable body size in urban, Ghanaian Women. Ghana Medical Journal, 46(2), 66–75.

Bimpong, K. A., Cheyuo, E. K. E., Abdul-Mumin, A., Ayanore, M. A., Kubuga, C. K., & Mogre, V. (2020). Mothers’ knowledge and attitudes regarding child feeding recommendations, complementary feeding practices and determinants of adequate diet. BMC Nutrition, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-020-00393-0

Blakemore, S.-J. (2019). Adolescence and mental health. The Lancet, 393(10185), 2030–2031. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31013-X

Bliznashka, L., Danaei, G., Fink, G., Flax, V. L., Thakwalakwa, C., & Jaacks, L. M. (2021). Cross-country comparison of dietary patterns and overweight and obesity among adult women in urban Sub-Saharan Africa. Public Health Nutrition, 24(6), 1393–1403. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019005202

Bragg, M. A., Hardoby, T., Pandit, N. G., Raji, Y. R., & Ogedegbe, G. (2017). A content analysis of outdoor non-alcoholic beverage advertisements in Ghana. British Medical Journal Open, 7(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012313

Brouwer, I. D., McDermott, J., & Ruben, R. (2020). Food systems everywhere: Improving relevance in practice. Global Food Security, 26, 100398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100398

Buxton, A. C. N. (2014). Ghanaian junior high school adolescents dietary practices and food preferences: Implications for public health concern. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences, 4(5). https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9600.1000297

Caulfield, L. E., Richard, S. A., Rivera, J. A., Musgrove, P., & Black, R. E. (2006). Stunting, wasting, and micronutrient deficiency disorders. In D. T. Jamison, J. G. Breman, A. R. Measham, G. Alleyne, M. Claeson, D. B. Evans, P. Jha, A. Mills, & P. Musgrove (Eds.), Disease control priorities in developing countries (2nd ed.). World Bank.

Clapp, J. (2014). Financialization, distance and global food politics. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(5), 797–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2013.875536

Clapp, J., Moseley, W. G., Burlingame, B., & Termine, P. (2022). Viewpoint: The case for a six-dimensional food security framework. Food Policy, 106, 102164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102164

Crouch, S. H., Soepnel, L. M., Kolkenbeck-Ruh, A., Maposa, I., Naidoo, S., Davies, J., Norris, S. A., & Ware, L. J. (2022). Paediatric hypertension in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 43, 101229–101229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101229

Darkwa, S. (2014). Knowledge of nutrition facts on food labels and their impact on food choices on consumers in Koforidua, Ghana: A case study. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 27(1), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/16070658.2014.11734479

Darling, A. M., Sunguya, B., Ismail, A., Manu, A., Canavan, C., Assefa, N., Sie, A., Fawzi, W., Sudfeld, C., & Guwattude, D. (2020). Gender differences in nutritional status, diet and physical activity among adolescents in eight countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 25(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13330

Development Initiatives. (2021). 2021 global nutrition report.

Fanzo, J., Covic, N., Dobermann, A., Henson, S., Herrero, M., Pingali, P., & Staal, S. (2020). A research vision for food systems in the 2020s: Defying the status quo. Global Food Security, 26, 100397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100397

FAO. (2020). Support to the planting for food and jobs campaign.

Fernandes, M., Folson, G., Aurino, E., & Gelli, A. (2017). A free lunch or a walk back home? The school food environment and dietary behaviours among children and adolescents in Ghana. Food Security, 9(5), 1073–1090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-017-0712-0

Ganle, J. K., Boakye, P. P., & Baatiema, L. (2019). Childhood obesity in urban Ghana: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey of in-school children aged 5–16 years. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7898-3

Ghana Statistical Service, Ghana Health Service, & ICF International. (2015). Ghana demographic and health survey 2014 (No. 233302682661/2). Retrieved May 5, 2023, from www.DHSprogram.com

Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition. (2014). How can agriculture and food system policies improve nutrition.

Gyasi, R. M., Peprah, P., & Appiah, D. O. (2020). Association of food insecurity with psychological disorders: Results of a population-based study among older people in Ghana. Journal of Affective Disorders, 270, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.088

Hargreaves, D., Mates, E., Menon, P., Alderman, H., Devakumar, D., Fawzi, W., Greenfield, G., Hammoudeh, W., He, S., Lahiri, A., Liu, Z., Nguyen, P. H., Sethi, V., Wang, H., Neufeld, L. M., & Patton, G. C. (2022). Strategies and interventions for healthy adolescent growth, nutrition, and development. The Lancet, 399(10320), 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01593-2

Hawkes, C. (2006). Uneven dietary development: Linking the policies and processes of globalization with the nutrition transition, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases. Globalization and Health, 2(1), 4–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-2-4

Hawkes, C., Friel, S., Lobstein, T., & Lang, T. (2012). Linking agricultural policies with obesity and noncommunicable diseases: A new perspective for a globalising world. Food Policy, 37(3), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.02.011

Herforth, A., & Ahmed, S. (2015). The food environment, its effects on dietary consumption, and potential for measurement within agriculture-nutrition interventions. Food Security, 7(3), 505–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0455-8

HLPE. (2017). Nutrition and food systems. A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security. Retrieved August 21, 2023, from www.fao.org/cfs/cfs-hlpe

Holdsworth, M., Pradeilles, R., Tandoh, A., Green, M., Wanjohi, M., Zotor, F., Asiki, G., Klomegah, S., Abdul-Haq, Z., Osei-Kwasi, H., Akparibo, R., Bricas, N., Auma, C., Griffiths, P., & Laar, A. (2020). Unhealthy eating practices of city-dwelling Africans in deprived neighbourhoods: Evidence for policy action from Ghana and Kenya. Global Food Security, 26, 100452–100452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100452

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), I. F. P. (2019). Food system innovations for healthier diets in low and middle-income countries. https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.133156

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), I. F. P. (2020). 2020 global food policy report: building inclusive food systems. https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896293670

Intiful, F. D., & Lartey, A. (2014). Breakfast habits among school children in selected communities in the eastern region of Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal, 48(2), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.4314/gmj.v48i2.3

Jonah, C. M. P., Sambu, W. C., & May, J. D. (2018). A comparative analysis of socioeconomic inequities in stunting: A case of three middle-income African countries. Archives of Public Health, 76(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-018-0320-2

Keats, E. C., Rappaport, A. I., Shah, S., Oh, C., Jain, R., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2018). The dietary intake and practices of adolescent girls in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Nutrients, 10(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10121978

Koplan, J. P., Liverman, C. T., & Kraak, V. (2005). Preventing childhood obesity: Health in the balance (p. 11015). Institute of Medicine of The National Academies. https://doi.org/10.17226/11015

Laar, A., Barnes, A., Aryeetey, R., Tandoh, A., Bash, K., Mensah, K., Zotor, F., Vandevijvere, S., & Holdsworth, M. (2020). Implementation of healthy food environment policies to prevent nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in Ghana: National experts’ assessment of government action. Food Policy, 93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101907

Lawrence, M. A., Friel, S., Wingrove, K., James, S. W., & Candy, S. (2015). Formulating policy activities to promote healthy and sustainable diets. Public Health Nutrition, 18(13), 2333–2340. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015002529

Linderhof, V., Vlijm, R., Pinto, V., Raaijmakers, I., & Dijkshoorn-Dekker, M. (2019). Urban food security in Ghana: A policy review. https://doi.org/10.18174/476849

Manyanga, T., El-Sayed, H., Doku, D. T., & Randall, J. R. (2014). The prevalence of underweight, overweight, obesity and associated risk factors among school-going adolescents in seven African countries. BMC Public Health, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-887

Masters, W. A., Bai, Y., Herforth, A., Sarpong, D. B., Mishili, F., Kinabo, J., & Coates, J. C. (2018). Measuring the affordability of nutritious diets in africa: Price indexes for diet diversity and the cost of nutrient adequacy. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(5), 1285–1301. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay059

Masters, W. A., Rosenblum, N. Z., & Alemu, R. G. (2018). Agricultural transformation, nutrition transition and food policy in Africa: Preston curves reveal new stylised facts. Journal of Development Studies, 54(5), 788–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1430768