Abstract

Where maize plays a critical role in food security, governments and donors have invested heavily in support of local, privately owned, often small and medium sized, maize seed enterprises (maize SMEs). Underpinning these investments are strong assumptions about maize SMEs’ capacity to produce and distribute seed to smallholders. This study assesses the capacities of 22 maize SMEs in Mexico that engaged with MasAgro—a large-scale development program initiated in 2011 that has provided maize SMEs with improved genetic material and technical assistance. Data were collected onsite from in-depth interviews with enterprise owners and managers and complemented with other primary and secondary sources. Overall, maize SMEs showed high levels of absorptive capacity for seed production, but limited signs of learning and innovation in terms of business organization and strategic seed marketing. Asset endowments varied widely among the SMEs, but generally they were lowest among the smaller enterprises, and access to business development services beyond MasAgro was practically nonexistent. Results highlighted the critical role of MasAgro in reinvigorating the portfolios of seeds produced by maize SMEs, as well as the challenges ahead for maize SMEs to scale the new technologies in a competitive market that has long been dominated by multinational seed enterprises. Among these challenges were limited investment in seed marketing, weak infrastructure for seed production, and limited experience in business management. Achieving the food security goals through maize SMEs will require making national maize seed industry development a strategic imperative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Breeding for improved maize cultivars that meets the needs of smallholders has long been a development priority in regions where maize plays a critical role in food security (Byerlee & Heisey, 1996; Afari-Sefa et al., 2012; Custodio et al., 2016; Qaim, 2020). Major donor-driven programs, to include the Crops to End Hunger initiative (CGIAR, 2018), are justified on the idea that plant breeding contributes to improved farming productivity, higher farm-derived income, and reduced vulnerability of smallholder production in the face of climate change. The CGIAR, working with national agricultural research systems (NARS) and the private sector, has achieved high returns to investment from the introduction of genetic innovation relevant for smallholder production of staple food crops, including maize (Evenson & Gollin, 2003; Renkow & Byerlee, 2010), despite debates over the data, methods, and assumptions used to estimate such returns (Hurley et al., 2014). Recent donor investments in maize breeding for strengthening food security in tropical rainfed environments have sought to increase resilience to drought and pests (Prasanna et al., 2021a, b), as well as enhance the nutrition content of maize (Prasanna et al., 2020). Various studies have documented the potential benefits of adoption of improved maize cultivars on smallholder production systems and rural livelihoods (Khonje et al., 2015; Mathenge et al., 2014; Raghu et al., 2015; Smale & Mason, 2014).

Looking ahead, a key challenge for breeding programs, including those for maize, lies in achieving faster adoption at greater scale of genetic innovations (Krishna et al., 2014; Spielman & Smale, 2017; Rutsaert et al., 2021). The potential contributions of plant breeding to food security goals can only materialize when improved cultivars are used by farmers. Donor supported maize breeding programs rely heavily on ‘public–private partnerships’ (PPPs) with locally based, privately owned, small and medium sized, seed enterprises (identified henceforth as maize SMEs) for achieving impact. Although being a key scaling partner, this category of private sector actors has received little attention compared to informal seed producers (localized seed banks or enterprises managed by farmer cooperatives or women’s groups) or larger – often multinational crop science firms. Within PPP arrangements, breeding programs typically provide free-of-charge, sometimes exclusive, access of maize cultivars, and in return, maize SMEs multiply the cultivars and market them to farmers, either directly or via retail networks. Seed companies assume the risks (e.g. regulatory, climate, financial) to produce and market the new varieties (Spielman et al., 2007). Studies have highlighted the rapid emergence of maize seed industries in India (e.g. Morris et al., 1998) and eastern and southern Africa (e.g. Erenstein & Kassie, 2018), with dozens of maize SMEs having been established over recent years.

1.1 Maize in Mexico

In Mexico—a country where maize production has long played a central role in cultural, economic, and political interactions—research on maize seed systems has concentrated on informal seed multiplication and exchange, and the related implications for biodiversity conservation (e.g. Badstue et al., 2006; Carro-Ripalda & Astier, 2014; Louette et al., 1997). This focus on the informal reflects, in large part, the considerable genetic diversity that exists in maize in Mexico (Brush & Perales, 2007) and the critical role of smallholders in maintaining that diversity. In highlighting the importance of informal maize seed systems, researchers have discouraged the design of food security strategies focused on the production of improved maize cultivars. One argument highlights the resistance of smallholders in central and southern Mexico to the modernization of maize production, expressed, in part, by their choice to use locally adopted landraces in the face of government pressure to adopt hybrids (Mullaney, 2014). Many smallholders in central and southern Mexico may prefer to produce maize landraces for culinary, agronomic and cultural reasons (Bellon & Hellin, 2011).Footnote 1 Keleman and Hellin (2009) discussed the influence of culture, combined with government programs aimed at rural poverty, on fostering the retention of landraces. In addition, a growing market for specialty maize may provide economic incentives for some smallholders to maintain their landraces (Bellon & Hellin, 2011). A study in central Oaxaca (Rodríguez & Aragón, 2015) found that 95% of maize farmers had never used improved varieties due to their cost (vis-à-vis farmer-saved seed) and lack of information on where to acquire them and their potential benefits. Little is known about the overall contribution of specific landraces to maize supply, as official data converge on maize production beyond the white versus yellow clarification are patchy.

Yet, the government of Mexico’s approach to food security has consistently been linked to the production of maize hybrids. Since the mid-twenty century, government and donor-supported programs have considered the production and distribution of maize hybrids as the most promising path towards meeting food security goals and national self-reliance in maize (Fitzgerald, 1986; Matchett, 2006). Similar to the emergence of maize seed industries in India and eastern and southern Africa, the growth of the Mexican seed industry can be traced to the early 1990s following modification the seed regulatory framework which allowed the private sector to engage in the research, development and delivery of improved maize cultivars. With market liberalization came multinational seed enterprises that quickly captured a significant share of the Mexican seed market, peaking at 90% in the early 2000s (Luna et al., 2012). Multinational seed companies, having built their reputations by supplying hybrids in the highly productive irrigated areas of northwestern Mexico, now dominate maize seed sales throughout the country, including in the rainfed production areas of central and southern Mexico.

Early public investments in hybrid maize can be considered to have been successful from a national food security perspective. Farmers in many states of Mexico depend extensively on improved seed for their maize production. Most farmers in Sinaloa, Jalisco and Michoacán utilize hybrids, with the percentage of total area in the state covered with improved seed ranging from 85 to 100% (Fig. 1). The relatively large-scale producers in these states invested in irrigation and aggressively adopted hybrids shortly after the first hybrids were introduced. Uptake of improved seed has expanded to parts of central and southern Mexico. In Chiapas, Veracruz and Puebla, for example, improved-seed coverage is estimated at 35%, 52% and 42%, respectively. These states, with their large areas of relatively low yielding maize production, represent a plausible opportunity for increased utilization of hybrid maize adapted to local climatic conditions. Between 2011 and 2018, on average, 89,880 MT of improved maize seed was marketed in Mexico, with a high of 98,910 MT in 2016 and a low of 61,392 MT in 2012. Multinational seed companies—three major ones currently operate in Mexico—have consistently dominated the market, averaging about 80% of total sales (Fig. 2). According to available retail price data for certified maize seed collected by SNICS (2017), the average retail price for seed produced by multinational seed companies was USD 6.1/kg, compared to USD 3.8/kg for seed produced by Mexican-owned maize SMEs. Smaller scale and more recently established seed enterprises have tended to focus on building market share in the underserved states dominated by smallholders who grow maize under rainfed conditions (Rodríguez & Aragón, 2015).

Share of Mexican maize seed market captured by multinational and nationally based seed enterprises, 2011–2018*. *Estimates of seed sold by multinationals and other national seed enterprises are derived from SNICS reports on certified seed production and official import data. Estimates of seed sold by MasAgro affiliated seed enterprises are obtained from an annual survey administered since 2013 and include both certified and declared quality seeds. Estimates for MasAgro share may be overestimated, as no information on quality declared seed is available for seed enterprises not engaged with MasAgro, including multinational seed enterprises

In 2011, the government of Mexico financed the MasAgro programFootnote 2 to support maize SMEs to produce and deliver improved cultivars that would contribute to the goal of higher smallholder maize productivity (Donnet et al., 2012). MasAgro, a Spanish acronym which stands for Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture, was implemented by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). The program represented a strategic shift in government-backed efforts to support access to improved maize seeds by smallholders, work which traditionally had been led by national research institutes. Prior to MasAgro, national breeding research institutions supplied most of the cultivars acquired by maize SMEs. Between 2011–2018, Masagro released 48 maize hybrids with few restrictions (e.g. access to all cultivars, no royalties and autonomy in seed branding).Footnote 3 These hybrids and partial lines translated in 149 commercial products, as different companies could license and sell the same cultivar under a different brand. We refer to a commercial product as a branded maize hybrid that is available on the market. Maize cultivars derived from MasAgro were designed to perform across a range of rainfed circumstances and tolerate droughts and specific maize diseases. This was coupled with the program’s engagement with maize SMEs in designing product portfolios (e.g. participatory evaluation network for field trials of new hybrids) and adjusting seed production processes. Participating SMEs did not receive direct subsidies for seed research or seed production, nor were they offered guaranteed markets for their production of commercial products derived from MasAgro hybrids. Most maize SMEs in Mexico, some 85%, participated in the program. In 2018, the year in which most data were collected for this study, 60 maize SMEs engaged in the program.

1.2 Objectives and outline

This paper examines maize SMEs in Mexico that participated in MasAgro, and their capacity to produce new maize hybrids and commercialize these hybrids in a competitive seed market. In doing so, it reflects on the strategy of strengthening formal maize seed systems in a country where i) multinationals dominate the seed market and ii) landraces remain a fundamental part of smallholder maize production systems. Within this context, important questions arise regarding the ultimate goal seed systems development and whether maize SMEs are equipped to deliver on these. The remainder of this article is divided into five sections. Section 2 explores the broader discussions on SME development from the business management literature. Insights from these discussions provide the basis for formulation of research questions on maize SMEs in Mexico. Section 3 presents the methods used for data collection from a sample of MasAgro-affiliated maize SMEs and describes the context in which the study was carried out. Section 4 presents the results derived from the interviews with enterprise owners and managers. In Section 5, we explore the implications of the findings and opportunities for innovation in the design of interventions to support maize SMEs. Section 6 presents some concluding thoughts from this study.

2 Determinants of maize SME capacity

The potential for small and medium seed enterprises to contribute to food security goals has been documented in India (Pray & Ramaswami, 1999; Manjunatha et al., 2013) and parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Alemu et al., 2008; Guei et al., 2011; Kassie et al., 2013; Langyintuo et al., 2010; Tahirou et al., 2009). In general, these accounts highlighted the rapid growth in the number of seed SMEs (e.g. maize, rice, cotton), in response to improved germplasm developed by the public sector and changes in the regulatory environment. The growth of seed SMEs responded to changes in the external environment, to include greater access to technologies, changes in regional trade policies, and continued government support for R&D. Discussions forewarned the reluctance of seed companies to invest in variety promotion and the corresponding need public sector to educate farmers on seed systems (Pal & Tripp, 2002). Spielman and Kennedy (2016) advocated for expanding the set of indicators to assess seed industry growth and development beyond to production volumes (and similar production related indicators), to include those related to performance, competition, and innovation. Overall, discussions in the seed systems literature have viewed seed SMEs more as vehicles for development programs to achieve impact, than as unique business operations with a diverse set of capacities, strategies and needs.

Solutions to some of the major challenges faced by donor-funded programming related to plant breeding and seed system development to further deliver on food security goals, to include the need for faster varietal turnover (Walker & Alwang, 2015) and better targeting of the ‘right’ products to the ‘right’ farmers (Cobb et al., 2019), will require deeper insights on seed SME incentives and capacities. These, in turn, should allow for the design of new approaches to support seed enterprise growth and development over time. The remainder of the section therefore provides a brief overview of the broader discussion on the determinants of SME capacity. While much of this discussion resides in the management literature and is focused on urban-based SMEs in advanced economies, the basic concepts around which SME capacity is framed are useful for considering the growth and development trajectories of maize SMEs in Mexico and elsewhere.

Since the 1980s, SME development has been a primary concern to governments and researchers interested in economic growth and poverty reduction. In the Global South, the underlying interest in SMEs reflects: 1) the large number of SMEs and their relevance to the urban and rural economies, 2) their nature as a critical source of income for the poor, and 3) the lack of government support, due partially to the informality prevalent in the SME sector (Hallberg, 2000). SME research within the management literature has focused on understanding the determinates of business performance and how performance is shaped by changes in regulatory environments and external support programs. In this section, we review two dimensions of the SME capacity discussion: asset endowments and absorptive capacity.

2.1 Asset endowments

Researchers exploring SME growth and development have placed considerable interest in how SMEs build their asset endowments over time and how these assets are deployed. An enterprise’s asset endowment at a given time is comprised by financial capital, social capital in the form of employment of skilled personnel with their in-house knowledge, and physical capital such as machinery and infrastructure (Wernerfelt, 1984). Higher levels of human and social capital endowments combined with other factors (e.g. entrepreneurial orientation) are considered important determinates of SME performance (Cassia & Minola, 2011; Debrulle et al., 2013; Onkelinx et al., 2015), including for SMEs in the Global South (Mansion & Bausch, 2020). However, SME performance depends not only on having high levels of asset endowments, but also on the capacity to deploy specific assets in the right combination (asset interconnectedness) at the right time (Sok et al., 2019). Researchers have also highlighted the positive correlation between SME owners–managers’ level of financial literacy and business performance (Eniola & Entebang, 2017; Quaye & Mensah, 2019). Higher marketing capabilities tend to be associated with better marketing performance, namely in branding and innovation in product design and management processes (Merrilees et al., 2011) and were more likely to achieve market expansion and innovation (Barbero et al., 2011).

Where SMEs lack critical assets, their engagement or alliances with other enterprises can promote growth and development. The rationale for alliances between other actors lies the value-creation potential of assets that are pooled together (Das & Teng, 2000), whereby firms seek a strategic fit between their internal characteristics (strengths and weaknesses) and their external environment (opportunities and threats). Alliances can serve as a type of strategic choice or an alternative that can enable companies to cope with unstable, global and competitive environments permeated by (new) threats and opportunities (Mamedio et al., 2019). For example, due to the high distribution costs and scattered rural demand, maize SMEs often rely on local retailers or agro-dealers for seed distribution. For seed production, outgrowers are considered a key partner for seed companies (Van Mele et al., 2011). Evidence on the effects of alliances of SME performance derives mainly from experiences of non-agricultural SMEs in the Global North. Brouthers et al. (2015) showed that SMEs performed better in international markets when engaged in strategic alliances for research and marketing, among other factors. Others have pointed out the role of strategic alliances for SMEs in building human capital (Ferreira & Franco, 2019), expanding the scope of marketing efforts (O’Dwyer et al., 2011), and penetrating markets that were dominated by major corporations (Lee et al., 2000).

2.2 Access to external services

In addition, access by SMEs to externally provided services, both financial and non-financial, can address gaps in asset endowments and thereby support their capacity development and overall performance (Kersten et al., 2017; Park et al., 2020; Robson & Bennett, 2000; Wilkinson & Brouthers, 2006). In the context of seed, various investments have been made to facilitate access by seed companies in Africa to early generation seed—a critical input for maintaining the genetic purity of breeding lines (Leon et al., 2015). Maize SMEs are likely to have high demand for credit given that costs are incurred throughout the year, while seed sales occur in the span of only a few weeks. Previous work looking at SMEs in the African seed sector has highlighted the lack of access to credit services as a barrier to development (e.g. ISSD, 2017; Langyintuo et al., 2010). In general, however, we know little about the needs of maize SMEs for external services, nor the availability or capacity of local providers to respond to these needs. The omission stands out in light of the critical importance of non-financial components to SME growth, to include marketing strategy (Slater & Olsen, 2001), process management (Škrinjar et al., 2008) and production efficiency (Burki & Terrell, 1998).

2.3 Absorptive capacity

A second important dimension of the SME discussion focusses on innovation and the ability of SMEs to integrate knowledge generated externally to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities (e.g. launch new products, modify managerial processes). In this context, discussion has focused on the concept of ‘absorptive capacity’ (AC), defined as the capacity of enterprises to identify, assimilate, and exploit outside knowledge. There is a relation between resources of SME and their absorptive capacity. Cohen and Levinthal (1990) discussed how enterprises build AC through investment in learning and innovation, to include contributions to R&D, direct (hands-on) engagement in production processes and investments in staff training. Recent research has tested the effects of AC on SME performance (e.g. innovation in product design and management practices, knowledge transfer, higher profits) in the technology and export (non-agricultural) sectors (Ferreras-Mendez et al., 2019; Sciascia et al., 2014). In broad terms, greater AC is expected to result in product innovation (e.g. incorporation of new hybrids into product portfolio) and process innovation (e.g. strategy for expanding seed sales) and, ultimately, lead to greater profitability. Researchers have highlighted the ability of SMEs to increase their AC for new product development through closer and more frequent engagements with customers and suppliers and retailers (Tzokas et al., 2015; Scuotto et al., 2017). Within the context of maize SMEs AC can be expressed in various ways. Among these are: i) the uptake of new cultivars from breeding organizations (to include on site testing, experimentation with production techniques), ii) innovation in the design of arrangements with partners (e.g. retailers, outgrowers), and iii) new forms of marketing seed to farmers (either directly or through retail partners).

3 Methods

3.1 Sample frame

Primary data was collected in Mexico in 2018 through a seed company survey. The precise number of seed companies with active commercial operations in Mexico is unknown. While the official data sources identify 403 companies, many of these are single companies registered under two or more names or companies but have never produced seeds on a commercial basis. Seed system specialists at CIMMYT identified 89 unique seed enterprises (85 of which were locally owned and four multinational companies) that have actually produced seed in recent years. Among these, 81 of the locally owned enterprises had participated over some period in the MasAgro program. In 2017, when our sample was designed, 60 maize SMEs actively participated in the program. Enterprises who had less than two years of collaboration with MasAgro were excluded (as they were unlikely to have been able to launch new commercial products derived from MasAgro cultivars in such a short time frame), as well as those located in the state of Guerrero (due to security concerns and travel restrictions), reducing the eligible population of active MasAgro members to 41. Our sample included 22 of these enterprises, or about 50% of the eligible population of MasAgro-established participants in 2017. Using preexisting data from the MasAgro program, seed enterprises were selected at random from three regions: west (Guanajuato, Michoacán, Jalisco and Colima), central (Puebla, state of Mexico, Morelos, Hidalgo and Queretaro) and other (Veracruz, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Campeche, Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Durango and Coahuila).

Table 1 provides an overview of the sampled maize SMEs. According to official definitions, all these enterprises can be classified as micro (less than 20 employees) or small (20–49 employees) (OECD, 2017). To gain insights into how absorptive capacity and asset endowments varied across the sample, the enterprises were classified into three groups based on the average volume of maize seed produced 2017–2019:

-

Low-volume group (LVG): produced less than 100 MT of maize seed per year, with most of the enterprises based in the central and ‘other’ regions, where uptake of hybrid seeds has traditionally been lower. These enterprises, on average, had operated for 9 years.

-

Medium-volume group (MVG): producing between 100–400 MT of maize seed per year, located primarily in the western region. The average age of these enterprises, at 12 years, was slightly higher than those of LVG.

-

High-volume group (HVG): produced more than 400 MT of maize seed per year, located primarily in the western region. These enterprises tended to be relatively older than those in LVG and MVG, with an average age of 22 years.

3.2 Survey design and data collection

The survey was designed to shed light on the asset endowments and the absorptive capacity of maize SMEs. We took stock of existing assets endowments, including those related to physical capital (e.g. machines and infrastructure for production), human capital (e.g. staffing, experience, planning processes) and social capital (e.g. business relations with outgrowers, seed retailers and producer organizations). Questions sought insights into strategic alliances with retailers and other maize SMEs, as well as access to external services, both financial and non-financial, from commercial providers (banks, consultants), government agencies, NGOs, and others, including MasAgro. The survey sought insights into absorptive capacity as related to seed production (e.g. launching of new commercial products and sources of cultivars), as well as in marketing and management (e.g. marketing strategies and tactics employed, pricing strategies, market information sources). The survey concluded with interviewees providing their perspectives on critical limitations faced for the production and marketing of hybrid maize seed.

The survey was implemented with selected representatives within the maize SMEs, usually the owner, head of production and head of marketing. In the case of some smaller enterprises, only the owner, who often also led production and marketing operations, participated. Interviews consisted of one face-to-face-interview, which typically lasted two hours, and one or more short phone interviews to fill in data gaps and seek clarifications. The interviews were conducted in Spanish and the data collection team consisted of one interviewer and two note takers. Both qualitative as well as quantitative data were captured during the interviews. After each interview, notes on the qualitative open-ended questions were combined and reviewed by the data collection team. The quantitative data were analyzed with SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), although the low sample size did not warrant statistical analysis beyond descriptive statistics. The quantitative results comprise the main structure of the results section, further supplemented and deepened with insights and quotes of the open-ended questions.

Given the paucity of studies on maize SMEs and their contributions to the development objectives that underpin donor-funded plant breeding programs, we employed an inductive approach to knowledge generation, with the primary intention of informing future research and stimulating practitioner debate. We pulled ideas from two important lines of discussion within the boarder discussion on SME development, those related to asset endowments and absorptive capacity, to explore maize SMEs and their engagement in seed production and seed marketing.

4 Results

4.1 Asset endowments

4.1.1 Own assets

The median number of employees for LVG and MVG enterprises was 8 and 13, respectively, divided roughly equally between roles in administration, sales and seed production (mainly supervision of seed-producing outgrowers). The MVG enterprises tended to have, on average, five more employees who engaged in the processing of seeds, whereas this activity was often outsourced by enterprises in LVG. Enterprises in HVG maintained considerably higher numbers of staff, with a median of 36. In contrast to LVG and MVG enterprises, HVG enterprises maintained full-time staff dedicated to maize breeding (median = 8). Over the past five years, most of the maize SMEs reported to have increased or at least maintained their staffing. Across the groups, on average 20–25% of total staff employed were sales agents, with estimated average seed sales per sales staff of USD 174,000 (LVG), USD 365,000 (MVG) and USD 367,000 (HVG). Average annual sales per sales agent for enterprises in HVG were roughly twice as high as those of enterprises in LVG and MVG.

Most maize SME owners, before starting their enterprises, worked as maize breeders for government or international research centers. With a single exception, none of the seed-enterprise owners had acquired experience in management or marketing with the multinational seed companies before starting their enterprises. For example, four owners worked as breeders for INIFAP—Mexico’s National Institute for Agricultural, Forestry, and Fisheries Research, while the owners of five maize SMEs gained experience in maize breeding at CIMMYT. Other government agencies and research centers served as the training ground for future seed business owners of four maize SMEs.

In all, between 2012 and 2017, the maize SMEs spent about USD 11.1 million on infrastructure, with most of these expenditures (87%) having been made by HVG enterprises. Nearly three-quarters of the maize SMEs owned their own seed processing plant, although roughly half of these reported that their plants were old and needed replacement. Three of the enterprises had purchased new processing equipment in the past five years. The remaining quarter of the enterprises, all LVGs, contracted out seed-processing services. A similar trend applies to ownership of heavy equipment for seed production; approximately half of the enterprises had tractors (n = 13) and only two had mechanical harvesters or detasseling machines. In some cases, HVG enterprises invested in relatively costly infrastructure, including cold storage (n = 2), climate-controlled warehouses (n = 2) and research laboratories (n = 4). Five out of the eight HVG enterprises owned irrigation equipment to multiply foundation seed or carry out small-scale seed production research. Even fewer of these (n = 4) applied irrigation in the production of maize seed.

The maize SMEs tended to rent land for seed production, with the area rented varying considerably according to the size of the enterprises (Table 2). Two LVG enterprises produced all their seed by their own means given the difficulties they faced in trying to engage with outgrowers. In general, the higher the production volume, the more dependent maize SMEs were on outgrowers for seed production. Looking at total production area (including rented land for own production and area under outgrower management), about half of the maize SMEs reported a gradual increase. Reduction in area under production in a given year was largely due to production problems (e.g. lower than expected productivity) or lack of working capital (e.g. due to late payment by government agencies that purchased seeds).

4.1.2 Alliances to complement own assets

For the 2018 seed production (spring), enterprises in LVG, MVG and HVG engaged, on average, with 2, 6, and 22 outgrowers, respectively. In a few cases, enterprises in LVG worked with a single seed producer (n = 3), allowing them to maintain close supervision of the seed production and avoid the higher coordination costs associated with engaging multiple producers. As noted by some representatives, one of the reasons for not working with outgrowers was the risk of lowering the quality of the final product. Nearly all of the maize SMEs provided guidance and assistance to seed outgrowers to ensure quality and timely delivery. In most cases, the enterprises offered outgrowers seed at no cost. They also delivered fertilizer and other inputs, with repayment by producers at the time of seed delivery. Most enterprises, however, carried out critical steps in the seed production process on outgrowers’ farms (e.g. detasseling and roguing), ensuring quality control in seed production and reducing the labor costs faced by outgrowers. For a few of their outgrowers, enterprises in the HVG offered short-term credit; on average six outgrowers received credit. The overall limited capacity of the seed enterprises to offer any type of credit to their outgrowers may limit their capacity to engage with the more capable outgrowers. As noted by a manager from an HVG business, “For long, the multinational seed companies have offered local outgrowers generous credit packages and technical assistance—we just can’t compete with them for the best seed producers”.

All the maize SMEs confirmed their access to new cultivars, to include those provided by MasAgro and the public sector. However, none reported seeking out (or having access to) services for marketing support or business administration, and most maize SMEs reported serious limitations to access financial services. Between 2013–2017 only six maize SMEs achieved access to credit, where all of the funds were for infrastructure development and were provided by government agencies. Roughly 40% of the maize SMEs reported limited access to credit as one of the top three challenges for future growth and development (Table 8). Given the cash flow challenges inherent in maize seed business (ie, costs incurred throughout the year, while sales are concentered in a few months), access to external sources of credit can be critical to maintain operations, as well as make strategic investments. Owners and managers provided insights into the nature of the credit bottlenecks. One manager noted, “Given our low sales volumes, it is just not possible to access credit”. Another noted, “We cannot take risks with credit: our cashflow is too small and the government fails to pay us on time for the seed that we deliver”. Yet another noted “Despite seven years of asking, and we have yet to receive credit from the bank.”

4.2 Absorptive capacity

4.2.1 Uptake of cultivars

During 2011–2017, maize SMEs received about 44 MT of seed from MasAgro. Enterprises received inbred lines (a male or female) or a single cross line (male or female), which were used for maintaining or bulking inbred lines (for their seed banks), producing basic seed and producing directly commercial seed. The project also provided hybrids and open pollinated varieties (OPVs) for promotional activities, such as demonstration plots, by maize SMEs (Table 3). LVGs and HVGs received the largest volume of seed, with 48% and 39% of total seed distributed, respectively, going to these two groups. Foundation seed constituted a quarter of all seed provided (breeding lines and single crosses in similar quantities), of which roughly half was allocated to LVGs and MVGs, with the other half going to HVGs. Final products represented the largest proportion of seed delivered by the program. Most promotional seed received by enterprises in LVG and MVG was of the triple-cross hybrid type, while enterprises in HVG tended to receive seed of the single-cross hybrid type,Footnote 4 suggesting the different interests among maize SMEs in future seed production and marketing investments. In addition, INIFAP maintained its engagement with maize SMEs, including distribution of cultivars and engagement with enterprises on the performance of maize cultivars in experimental stations. While detailed data were not available on seed volumes distributed by INIFAP, during the 2009–2012 period, INIFAP provided a total 133.6 MT of seed to all seed enterprises in Mexico. This number is likely to have decreased during recent years as seed companies turned to MasAgro for access to new cultivars. The key difference made by MasAgro was the shift from supplying only parental seed for hybrids seed production to in addition supplying the breeder's seed that can be incorporated into companies own private activities.

In 2017, the sampled maize SMEs together sold 189 commercial products in the Mexican seed market. Most of these, about 68% (n = 129), were new cultivars; that is, cultivars introduced between 2013 and 2017. (Fig. 3). New cultivars accounted for approximately 81%, 86% and 60% of the seeds sold by enterprises in LVG, MVG and HVG, respectively. Table 4 looks at the sources of these commercial products. Of the 57 cultivars introduced during the period by HVG enterprises, some 54% were derived from CIMMYT cultivars provided through MasAgro. A somewhat similar trend appears with LVGs and MVGs, where 57% and 35%, respectively, of the new commercial products launched in the period were derived from cultivars supplied via MasAgro. The relatively high innovation capacity for seed production among enterprises in MVG and HVG was evidenced by their capacity to generate new commercial products from their own breeding efforts. LVG and MVG enterprises have not incorporated yet new CIMMYT cultivars into their research pipeline, as supported by seed provision figures in Table 4, despite almost 50% of foundation seed having been allocated to these enterprises. Traditionally, smaller-scale maize SMEs in Mexico have functioned as seed multipliers rather than as designers of new cultivars, a fact that helps explain the higher demand for triple-cross hybrids and open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) by enterprises in LVG.

Maize SMEs also removed commercial products from the market. During the same five-year period, 37 seeds were taken off the market, of which eight had been in the market for more than 11 years and 6 had been in the market between 6 and 10 years. Enterprises are likely to remove a commercial product from the market because it is obsolete (e.g. low yield or resistance to pests and diseases), there was limited access to parental lines, difficulty encountered in seed production (e.g. higher than expected production costs) or insufficient demand from farmers. In some cases, the decision to take an old but established commercial product off the market can imply considerable reductions in revenue over the short term.

4.2.2 Commercialization of cultivars

Ultimately, achieving significant returns from public investments in MasAgro depends, in part, on maize SMEs expanding their sales of newly launched commercial products derived from MasAgro supplied cultivars. Table 5 presents the average sales for each group from 2014 to 2017, by seed type and duration in market. Most of the commercial products produced by enterprises in LVG and MVG were triple-cross hybrids, which were relatively low cost to produce but which exhibited greater genetic variation than single-cross hybrids. Across all three groups, sales of OPVs—seeds that were the lowest cost to produce but exhibited the highest genetic variation—were relatively low. On average, a business in LVG tripled its sales of new (less than five years on market) triple-cross hybrids. One reason for the strong growth of new seeds was the lack of competition from older commercial products in the enterprises’ seed portfolio. Achievements in seed sales were especially impressive given that some 65% of the volume of these new commercial products were designed for planting in higher altitudes, where hybrid usage and overall maize yields have traditionally been low. A seed business in MVG or HVG likely managed to expand its market for new triple-cross hybrids, although considerable variation existed over the period and only in MVG case did sales of new triple-cross hybrids appear in the most-sold seed category. The bulk of the production of new hybrids commercial products by enterprises in MVG and HVG, 89% and 80%, respectively, was designed for planting in mid-altitude, subtropical regions, where hybrid use and overall maize yields are relatively high. For enterprises in the HVG, however, new single crosses represented the fastest growing seed type, with sales increasing dramatically during the four-year period. The production of single-cross hybrids formed a key element in the strategies of enterprises in HVG to compete head-on with multinational seed companies in terms of yield potential. It also allowed the larger locally owned enterprises to differentiate their products in an increasingly crowded market for triple-cross hybrids. In most cases, the enterprises themselves developed the parent lines from which the single-cross hybrids were derived.

The study looked for indications that maize SMEs were able to invest resources in innovative seed marketing techniques. As detailed in Table 5 and mentioned above, the average volumes of new triple-cross hybrids sold over the 4 years for which data was collected grew rapidly for new triple-cross hybrids launched by enterprises in LVG and MVG. Sales of new triple cross hybrids declined slightly for enterprises in HVG, but their sales of new single-cross hybrids increased dramatically. The lack of growth in volumes of sales for triple-cross hybrids by enterprises in HVG raises ominous questions about the ability of MasAgro to reach scale with smallholders. Moreover, overall sales volumes of the maize SMEs were low given the size of the Mexican maize seed market. The highest average volume reported by enterprises in MVG, at 147.4 MT (equivalent to roughly 3700 bags of seed), comprised roughly 1.6% of the national market. Among the major challenges most mentioned by the maize SMEs were those related to seed marketing (increasing sales of new seeds), overall business environment (e.g. proliferation of brands and variation in prices) and access to specialized services, among others.

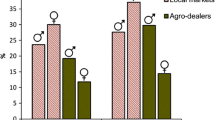

Less than 20% of the maize SMEs considered engagement at the point of sale to be useful for their seed marketing. They oriented their buyer engagement toward seed-sales retailers and the public sector, including the various local and state governments that purchased seed for free distribution to small-scale farmers (Table 6). The more established enterprises in MVG and HVG sold about 64% and 65%, respectively, of their 2018 seed production via retail networks. Business in LVG depended considerably less on retailers, potentially reflecting the high costs for maize SMEs to establish retail networks as well as the reluctance of retailers to dedicate scarce floor space to lesser-known commercial products. Seed sales to governments were considerable across the board. In some cases, sales to government represented more than 60% of total 2018 seed sales (n = 5). Looking at seed distribution channels, this trend is consistent across all the groups during the past three years of sales (2016–2018). Moreover, we observed a slightly higher relevance of direct sales to farmers to LVGs. As compared with retail and other marketing channels, government seed purchases reduced marketing risk and costs, but often at the expense of cumbersome acquisition processes and severely delayed payments. For maize SMEs eager to recuperate investments in seed production (and often without affordable access to credit), delayed government payments can have grave consequences, especially for enterprises in LVG and MVG. More than enterprises in any other group, those in LVG group attempted to sell seed through alternative distribution channels, namely the sale of seed directly to farmers and cooperatives.

Our survey examined the strategies pursued by maize SMEs to generate demand for their maize seed. Table 7 represents the marketing activities implemented by the maize SMEs in 2018 and the perceptions about the effectiveness of the activities. On average, the enterprises reported having implemented five activities for seed marketing. Among those considered critical for seed promotion, the implementation of demonstration plots stands out. Enterprises implemented between 10 and 40 demonstration plots, at a reported cost of USD 300 to USD 500 per plot (with labor inputs provided by participating farmers). Other marketing activities carried out and considered relevant for seed promotion included engagement with seed retailers, engagement in special events and commercial fairs and on-site visits with farmers. Overall, most maize SMEs employed a fairly standard set of marketing activities around demonstration plots, promotional materials and on-site visits to farmers, where a few ventured into social media, retail engagement and radio, with sometimes mixed results.

The maize SMEs were also asked specifically about their strategies and actions to capture market share from the multinational seed companies that have dominated the maize seed market for decades. In various cases, seed enterprises in LVG (n = 3) and MVG (n = 3) mentioned that they did not compete with multinational seed enterprises and therefore did not have a strategy or set of actions. Other seed companies, however, identified various elements of a strategy to compete with multinationals. The most reported element of their strategy (n = 15) was to offer seed with unique quality attributes (e.g. cultivars that were adapted to a particular production method, such as low input and rainfed, and cultivars that were high yielding, including single-cross hybrids). Thus, for many maize SMEs their engagement with MasAgro was opportune for expanding their seed portfolio. The second most identified strategic element was lower price. Eight of the enterprises reported that they compete with multinationals by offering seed significantly lower in price (30–50% lower). Other elements of their strategies included (1) application of advanced technology in seed production (n = 2 in HVGs), including double haploid and molecular markets, (2) focusing sales on areas where the multinationals have yet to deeply engage (n = 2 in LVG and MVG) and (3) providing reliable technical assistance and follow up on seed performance with farmers (n = 2 in LVG and MVG).

4.3 Perceived challenges

The maize SMEs perceived various challenges for their future growth and development (Table 8). First and foremost, enterprises identified challenges associated with the expansion of sales for new maize hybrids. Gaps specified included: (1) lack of skilled sales staff (and the associated costs to train staff), (2) insufficient budget for investment in marketing and (3) lack of cultivars that could compete with market leaders (strong competition from multinational seed companies). The second most identified challenge, competition with other seed enterprises, reflected among other issues: (1) the dominance of multinationals (and the need to capture market share from entrenched enterprises), (2) government distribution of free seeds purchased from a small number of enterprises and (3) proliferation of varieties and brands in the market (plus related uncertainties regarding relationships between price and quality).

5 Discussion

5.1 Asset endowments

Investments in physical capital accumulation were markedly lower among the smaller and newer enterprises of LVG and MVG. The results showed major constraints of these enterprises to acquire basic machines and infrastructure, from seed processing equipment to storage facilities and trucks for seed distribution. While a small seed company may survive with limited physical capital (e.g. by outsource processing, and selling seed locally), its future growth will likely depend, in part, on access to larger stocks of physical capital. The lack of physical capital among enterprises of the LVG and MVG reflects, in part, their limited access to financial capital. Empirical studies such as Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) and Zou and Chen (2008) argued that SMEs need financial capital to obtain physical capital to respond to business opportunities. Along similar lines, it has been shown that SME development requires that business owners and managers have access to a combination of assets, like human capital, physical capital, and financial capital, each playing same significant, but different, purpose over the life cycle of the business (Eniola & Entebang, 2015).

The contributions of human capital in the early stages of the SME business life cycle (e.g. attracting customers and building relationships with external stakeholders) are more significant than human capital obtained during later stages (Muda & Rahman, 2016). Among the maize SMEs, human capital was concentrated in seed production and processing, with a relatively small percentage (20–25% of total staff) dedicated to seed distribution and marketing. The relatively small sales staff implies that relatively limited attention is given to engagement with farmers on their seed preferences and resolving seed-related issues in maize production. Given that most owners and managers had previously worked in public breeding programs, attention and personal contact networks for marketing were likely to have been limited for enterprises in LVG and MVG. Interestingly, none of those whom we interviewed had experience working in the multi-national seed companies that have long dominated the industry. This explains a strong focus on designing new products and multiplying maize seed. This makes them business leaders with potentially limited understanding of how to build viable enterprises and influence the purchase decisions that farmers take on seed. Future growth in sales will require capable sales staff and some form of marketing activity, most probably a combination of products, prices, promotion and distribution (Carson et al., 1995). Recent research in eastern Africa has called attention to the urgent need for building the human capital in maize SMEs to better market seed to smallholders (Gharib et al., In Press; Rutsaert & Donovan, 2020).

While it is generally recognized that social capital contributes to SME performance, SME endowments of social capital in developing-country contexts tend to be low (Donovan et al., 2008, Clarke et al., 2016). The maize SMEs had built stock of social capital in terms of relations with retailers/distributors and government officials for the sale of maize seed. The engagement tended to be transactional in nature, limited to offer and purchase of seed. There was no indication that engagement by maize SMEs with retailers expanded into areas of knowledge sharing on farmer demand or innovation in seed marketing. Nor were there indications that maize SMEs engaged with seed industry associations or professional service providers (e.g. marketing consultants)—ties which have been considered important for SME growth in other sectors (Hunter & Lean, 2014). Studies on maize seed systems in Kenya have highlighted the limited engagement by seed companies in seed retail (Rutsaert & Donovan, 2020). Looking ahead, SME investments in building social capital are likely to deliver greater returns when paired with investments in building other assets, to include physical capital, human capital, leading to strengthen capacity for expanding their potential customer base and prospective market (Kim & Shim, 2018).

5.2 Alliances to complement own assets

Ensuring the needed volumes of quality seed implies careful management of the production process, to include pest control, planting patterns, nicking and pollen control. In most contexts, maize SMEs outsourced seed production, thereby allowing them to concentrate operations on product design and marketing, among other activities. However, enterprises from LVG grew their own seed or engaged with only a few outgrowers. This likely reflected the overall small volumes sold, but also suggested constrained financial flows for outsourcing production. The larger enterprises of HVG engaged extensively with outgrowers, offering them broad technical assistance in seed production, and in a few cases, access to seed production inputs on credit. Despite the vital role played by out-growers in the maize seed industry, our understanding of how competition among seed enterprises (including the multi-national enterprises that produce seed) shapes access to and engagement with out-growers remains limited. The extent to which maize SMEs can reduce the costs associated with supervision and technical support of out-grower production while maintaining high quality seed standards may also merit attention, thus allowing for engaging more out-growers or offering of better terms.

While maize SMEs generally outsourced seed production (thus eliminating the need for extensive investments in land and farming machinery), they sought to acquire in house capacity for seed processing. The maize SMEs in MVG and HVG owned processing equipment, but in many cases, this was reported to be in need of replacement (e.g. secondhand equipment from formal state-owned seed operations). Most of the enterprises in LVG had yet to invest in processing equipment. Maize SMEs may continue to survive without major new investments in physical capital. However, maize SME development processes will depend, in part, on access to the right physical capital because processing capacity to clean and store seed allows better control over timing of product delivery (critical given the short time frame in which maize seed in sold during the year) and quality control.

5.3 Absorptive capacity

5.3.1 Uptake and turnover of the cultivars

Maize SMEs showed extraordinary high levels of absorptive capacity for the uptake of seed technology. Between 2013 and 2017, the SMEs launched 129 commercial products, most of them triple-cross hybrids, for sale in the Mexican market. For seed enterprises from LVG and MVG, new cultivars comprised most products available on the market at the time of data collection. Enterprises in HVG launched new single cross hybrids and incorporated lines from MasAgro into their own breeding research program to deliver unique commercial products adapted to specific growing conditions. Results showed that maize SMEs removed commercial products from the market after gaining experience in production and marketing: roughly 30% of the MasAgro derived commercial products which was introduced in the market since 2011, was later removed due to high production costs or lack of sales. Nonetheless, the overall expansion of new commercial products across maize SMEs during the 5-year period under observation in this study is notable and quite different from the slow varietal turnover in eastern and southern Africa (Walker & Alwang, 2015). However, it should also be acknowledged that major differences exist between the regulatory framework in Mexico and most African countries. As compared to Mexico, seed regulations in Africa tend to be more rigid (Spielman & Smale, 2017), with limited options for seed companies to self-certify their seed, mandates that variety codes be printed on seed bags, and restrictions on access (exclusive access to a variety by a single company).

Whether enterprises in LVG and MVG will be able to sustain their expansion and renewal of commercial products following the recent closure of MasAgro remains an open question. MasAgro worked largely independent of the public agencies charged with the development of the formal maize seed system. This, in part, allowed the program to move relatively quickly in producing quality cultivars and supporting acquisition by seed enterprises. The program overlooked the possibility of supporting maize SMEs growth through links with other types of service providers (e.g. enterprises, marketing consultants, commercial banks). Maize SMEs looking to promote sales of new commercial products or expand into new regions lack even the most basic data on seed markets. A clearly defined exit-strategy by MasAgro that covers how the current support to maize SMEs will be maintained after the program eventually terminates is urgently needed, else there is considerable risk that these companies will not be willing or able to continue the expansion and renovation of their seed portfolio in the future. In addition, various pre-existing recourses likely facilitated the uptake of MasAgro-derived cultivars, including pre-existing relations with seed out-growers and infrastructure for seed processing and distribution.

The broader SME literature also considers international competition as a factor in driving absorption capacity (e.g. Chandrashekar & Subrahmanya, 2017; Rodriguez-Serrano & Martin-Armario, 2019). The perceived need of maize SMEs to better compete with other maize SMEs and with multinational seed companies, likely played a role in their investments in varietal development. Another key external factor was the relatively easy access to new cultivars made available through MasAgro. The majority (roughly 70%) of new commercial products launched during the 5-year period of observation originated from cultivars supplied by external sources, of which MasAgro was, by far, the most important external source, especially for LVGs. As mentioned, MasAgro filled a gap that had long existed in publicly supported breeding programs, providing easy access, without royalties or branding conditions, and without the need for certification.

5.3.2 Commercialization of the cultivars

Given the high degree of competition in the maize seed sector, combined with the overall challenge of marketing seeds to smallholders, we considered innovation in marketing critical for getting new products into the hands of farmers. The data on seed production by seed type and time in the market made clear the need for bold and innovative approaches to seed marketing by the SMEs: nearly 85% of the products sold by enterprises in LVG and MGV had been in the market for less than 5 years. At the same time, most maize SMEs listed as their primary challenge the need for ‘expansion of sales for new commercial products’. But less than 20% of the maize SMEs considered engagement at the point of sale to be useful for the seed marketing.

However, signs of innovation in seed marketing were limited. Seed companies relied on a tried-and-true set of approaches and tools that sought to pull demand from farmers: demonstration plots where one or more commercial products are grown for farmers to observe their traits in nearby fields, support for lead farmers (e.g. provision of seed and services at no cost) and hiring of locally embedded sales agents to build demand and brand recognition for their new commercial products. The effectiveness of these tactics has yet to be shown in the maize seed systems literature. However, they are likely to be expensive to implement at scale, especially when compared to marketing through wholesale and retail distribution networks (Hardesty & Leff, 2010). While recognition that high levels of marketing capacity are essential to increase seed uptake by farmers, especially for new cultivars (Heiman & Hildebrandt, 2018), discussions in this area remain infrequent.

Maize SMEs sold sizable percentages of seed to local and state governments, more than 60% in some cases. The dependance on government sales was consistent across the three groups of maize SMEs. Engagement with government agencies provided clear benefits (e.g. lower marketing costs) but also costs (e.g. delayed payments) and risks (e.g. noncompetitive selection processes). Research has already pointed out the challenges of government and NGO distribution of seed to smallholders and its effect on economically sustainable seed sector (Mutonodzo-Davies & Magunda, 2011; Wiggins & Cromwell, 1995). The lack of innovation in maize seed marketing found among maize SMEs in Mexico reflected, among other things, a dependence on public-sector sales. The long-term growth and development of these maize SMEs will rest, in part, on the willingness of the public sector to support innovation in seed marketing, and the ability of maize SMEs to reach farmers with new products at affordable prices, rather than just getting more seed to farmers.

To the best of our knowledge, seed system research has yet to explore the role of branding and price to innovate the marketing of seed to smallholders. As noted in the study context (Sect. 1.1), the products of multinational seed enterprises in Mexico were priced considerably higher than comparable products from locally owned maize SMEs. The price difference may reflect superiority of hybrid products by multinationals, but it may also reflect the effect of their large investments in seed marketing over decades. In general, when consumers are unable to judge easily the quality of a given product (e.g. consumer electronics), price and brand serve as important indicators of quality (Wolinsky, 1983). Brand recognition is likely to be highly localized for most products sold by enterprises in LVG and MVG, given the small volumes sold, the predominance of new products, and the recent formation of the enterprises themselves. Where farmers judge seed quality on price —a strong possibility given the overall lack of information on seed performance available to farmers at the point of sale—the current tactics of maize SMEs based on underpricing multinational seed companies may be ineffective over the long term. Maize SMEs could set their seed price at the same level of that of multinationals but increase margins of retailers (resulting in higher retailer surplus) and use their vested interest and position to “push” their products to consumers (Ailawadi et al., 2009). However, such tactics would not negate the long-term investment needed by seed companies in building their brand based on reliable performance in the field.

6 Conclusions

Government and donor support for maize breeding programs remains grounded in the idea that competitive markets provide sufficient motivation for maize SMEs to produce new seeds and replace existing seeds on the market with new ones (Atlin et al., 2017). However, our study suggests that breeding programs that focus on breeding by maize SMEs without due attention to the bottlenecks on SME development, in general, and seed marketing, in particular, are unlikely to achieve their anticipated impact on food security. The rapid uptake and growth in production volumes of commercial products derived wholly or in part from MasAgro supplied cultivars was impressive. However, when viewed from the broader maize seed industry context, the gains become less impressive: multi-national seed enterprises dominated the market; strategies by MasAgro-affiliated enterprises in HVG, potentially the most important partners for achieving growth in production volumes for MasAgro derived products, were increasingly oriented towards single-cross hybrids for larger-scale commercial farmers; while maize SMEs in LVG and MVG struggled to build their market share for their new triple-cross hybrids often in parts of Mexico where hybrid uptake had traditionally been lower. It remains unclear how the Mexican government views the growth and development of maize SMEs for meeting the current and future demand of maize smallholders for improved cultivars. However, given the pressures facing Mexico in terms of climate change (Ureta et al., 2020) and associated increases in drought and disease pressure, we argue that a strong case exists for supporting the capacity of maize SMEs to build markets for stress tolerant hybrids for meeting the food security goals of the Mexican government. Maize SMEs potentially have a role in designing products and building markets for improved local varieties in those areas where hybrid uptake by smallholders has traditionally lagged (e.g. participatory breeding, on-farm testing).

The framework applied in this study showed high levels of absorptive capacity by maize SMEs for product design and production, i.e. variety development and seed production. Preexisting asset endowments in the form of human capital and alliances to enable seed production, combined with effective access to cultivars from MasAgro, played important roles in the rapid absorption of new cultivars. However, among enterprises in LVG and MVG, we detected limited attention for the commercialization side, showing low absorptive capacity for marketing innovation. There has been too little discussion on how to support innovation by maize SMEs in seed marketing across different contexts. A rebalancing of objectives would consider direct support to maize SMEs to build absorptive capacity for marketing and address critical gaps in asset endowments, as well as efforts to support a more enabling environment for long term enterprise growth and development. This will require new approaches to program design that recognize the need for multi-dimensional support services to maize SMEs over time, to include strategic planning and management, design of retail networks, packaging and branding, pricing strategy, access to affordable finance, and strategic alliances/joint ventures.

An argument for working with maize SMEs in Mexico is that they are more likely to maintain closer links to farming communities in areas where hybrid uptake has traditionally been lower, thereby offering a clearer pathway to achieving the food security goals that provided the underlying justification for public investment. How to target the right maize SMEs, therefore, emerges as an important issue. The results showed considerable variation in terms of strategies, capacities, and needs among maize SMEs. In the MasAgro context, marketing support targeted at enterprises from LVG and MVG might have offered higher returns in terms of hybrid sales to farmers who had traditionally used OPVs, for example. However, MasAgro supported all maize SMEs looking for access to new cultivars and it provided easy and unconditional access. The majority of these were based in those parts of Mexico where hybrid uptake was already high. Future engagement could benefit from a two-pronged approach, whereby one line of work focuses on getting new cultivars into the operations of as many maize SMEs as possible, and a second line engages those maize SMEs that are willing to seek out smallholders who have yet to adopt hybrid seed.

The role of the public sector in building a vibrant national maize seed industry also merits attention. Traditionally, in Mexico and elsewhere, the role of government has been primarily limited to establishing the regulatory framework for private sector engagement in seed production, to include seed quality assurance. Direct support to seed companies has typically been left to NGOs, CGIAR, and others. The reluctance for direct public-sector engagement suggests a deep-rooted belief that maize SMEs can build their enterprises over time in a way which contributes meaningfully to food security goals. The results here cast doubt on that assumption. Achieving these goals will require making national maize seed industry development a strategic imperative. The public sector needs to be active in promoting capacity-building measures, to include improving the access of maize SMEs to funds and capital, facilitating timely information on seed markets, and reducing the risks faced by seed companies to expand their markets. The potential for public sector engagement also extends to improving the larger business environment in which maize SMEs operate, for example, smallholder-oriented ‘buy local’ campaigns that highlight the potential cost and performance advantages of locally produced hybrids in and information campaigns on the benefits, risks and requirements of different seed options. Bringing concrete next steps and partnerships to the table for advancing food security goals through maize seed systems development starts with recognizing the need for realistic ambitions about maize SMEs and their growth pathways.

Change history

07 February 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-022-01265-0

Notes

Researchers attribute various reasons for the lower adoption of maize hybrids in central and southern Mexico. Some have argued that the poor performance of hybrids in less-favored production zones discourages uptake (e.g. Arellano Hernández & Arriaga Jordán, 2001), while others attributed low adoption to smallholders’ lack of familiarity with hybrids (Bellon et al., 2005). Lack of affordable credit was also suggested as a factor that limits the uptake (Turrent Fernandez et al., 2012), along with weak producer organizations and the overall decline of the public sector’s engagement in seed distribution (including the provision of extension services).

MasAgro was originally planned for a ten-year period 2011–2020. The implementation framework agreement between CIMMYT and the Government of Mexico was revised halfway through this implementation period whereby the 2020 end date was extended. Agreements have been renewed on an annual basis since 2020. In 2021 the program was renamed Crops for Mexico.

Seed enterprises have the option to certify their seed or not, although certification is necessary for commercial products derived from cultivars supplied by government breeding programs.

A single-cross is the hybrid progeny from a pollination between two homozygous inbred lines. Single-cross hybrid is uniform in appearance, maturity, and yield potentials and it exhibits high vigor and productivity. For seed companies, it has the disadvantage of being relatively expensive to produce. A three-way cross is the progeny from a cross between a single-cross hybrid and a third inbred line. Compared to a single cross, the hybrid progeny will be more diverse genetically and less uniform, but it has the advantage that the seed is produced from a single cross instead of an inbred line. For more details, see Seper and Poehlman (2006).

References

Afari-Sefa, V., Tenkouano, A., Ojiewo, C. O., Keatinge, J. D. H., & Hughes, J. D. A. (2012). Vegetable breeding in Africa: Constraints, complexity and contributions towards achieving food and nutritional security. Food Security, 4, 115–127.

Alemu, D., Mwangi, W., Nigussie, M., & Spielman, D. (2008). The maize seed system in Ethiopia: Challenges and opportunities in drought prone areas. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 3(4), 305–314.

Ailawadi, K. L., Beauchamp, J. P., Donthu, N., Gauri, D. K., & Shankar, V. (2009). Communication and Promotion Decisions in Retailing: A Review and Directions for future research. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 42–55.

Arellano Hernández, A., & Arriaga Jordán, C. (2001). Why improved maize varieties are utopias in the highlands of central Mexico. Convergencia, 8(25), 255–276.

Atlin, G., Cairns, J., & Das, B. (2017). Rapid breeding and varietal replacement are critical to adoption of cropping systems in the developing world to climate change. Global Food Security, 12(2017), 31–37.

Badstue, L., Bellon, M., Berthaud, J., Juarez, X., Rosas, I., Solano, A. M., & Ramirez, A. (2006). Examining the role of collective action in an informal seed system: A case study from the central valleys of Oaxaca Mexico. Human Ecology, 34(2), 249–273.

Barbero, J., Casillas, J., & Feldman, H. (2011). Managerial capabilities and paths to growth as determinants of high-growth small and medium sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 29, 671–694.

Bellon, M. R., Hodson, D., Bergvinson, D., Beck, D., Martinez-Romero, M., & Montoya, Y. (2005). Targeting agricultural research to benefit poor farmers: Relating poverty mapping to maize environments in Mexico. Food Policy, 30(5–6), 476–492.

Bellon, M. R., & Hellin, J. (2011). Planting hybrids, keeping landraces: Agricultural modernization and tradition among small-scale maize famers in Chiapas Mexico. World Development, 39(8), 1434–1443.

Brouthers, K., Nakos, G., & Dimitratos, P. (2015). SME entrepreneurial orientation, international performance, and the moderating role of strategic alliances. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1161–1187.

Brush, S. A., & Perales, H. (2007). A maize landscape: Ethnicity and agro-biodiversity in Chiapas Mexico. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 121(3), 211–221.

Burki, A., & Terrell, D. (1998). Measuring production efficiency of small firms in Pakistan. World Development, 26(1), 155–169.

Byerlee, D., & Heisey, P. (1996). Past and potential impacts of maize research in sub-Saharan Africa: A critical assessment. Food Policy, 21(3), 255–277.

Carro-Ripalda, S., & Astier, M. (2014). Silenced voices, vital arguments: Smallholder farmers in the Mexican GM maize controversy. Agriculture and Human Values, 31, 655–663.

Carson, D. J., Cromie, S., McGowan, P., & Hill, J. (1995). Marketing and Entrepreneurship in SMEs: An Innovation Approach. Prentice-Hall.

Cassia, L., & Minola, T. (2011). Hyper-growth of SMEs: Toward a reconciliation of entrepreneurial orientation and strategic resources. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 18(2), 179–197.

CGIAR. (2018). Initiative on “Crops to End Hunger”: strategy and options for CGIAR support to plant breeding.

Chandrashekar, D., & Subrahmanya, M. H. B. (2017). Absorptive capacity as a determinate of innovation: A study of Bengaluru high-tech manufacturing cluster. Small Enterprise Research, 24(3), 290–315.

Clarke, R., Chandra, R., & Machado, M. (2016). SMEs and social capital: Exploring the Brazilian context. European Business Review, 28(1), 2–20.

Cobb, J. N., Juma, R. U., & Biswas, P. S. (2019). Enhancing the rate of genetic gain in public-sector plant breeding programs: Lessons from the breeder’s equation. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 132, 627–645.

Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128–152.

Custodio, M. C., Demont, M., Laborte, A., & Ynion, J. (2016). Improving food security in Asia through consumer-focused rice breeding. Global Food Security, 9, 19–28.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (2000). A resource-based theory of strategic alliances. Journal of Management, 26(1), 31–61.

Debrulle, J., Maes, J., & Sels, L. (2013). Start -up absorptive capacity: Does the owner’s human and social capital matter? International Small Busines Journal, 32(7), 777–801.

Donnet, L., Hellin, J., & Riis-Jacobsen, J. (2012). Linking agricultural research with the agribusiness community from a pro-poor perspective: the importance of human capital development. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 15 (special issue A), 99–103.

Donovan, J., Stoian, D., & Poole, N. (2008). Global review of rural community enterprises: the long and winding road to creating viable businesses, and potential shortcuts. Technical Series 29/Rural Enterprise Development Collection 2, CATIE, Turrialba, Costa Rica.

Eniola, A., & Entebang, H. (2015). SME firm performance-financial innovation and challenges. Procedia Social and Behavioral Science, 195, 334–342.

Eniola, A., & Entebang, H. (2017). SME managers and financial literacy. Global Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150917692063

Erenstein, O., & Kassie, G. T. (2018). Seeding eastern Africa’s maize revolution in the post-structural adjustment era: A review and comparative analysis of the formal maize seed sector. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 21(1), 39–52.

Evenson, R. E., & Gollin, D. (2003). Assessing the impact of the Green Revolution, 1960 to 2000. Science, 300(5620), 758–762.

Ferreira, A., & Franco, M. (2019). The influence of strategic alliances on human capital development applied to technology-based SMEs. EuroMed Journal of Business, 15(1), 65–85.

Ferreras-Mendez, J. L., Fernandez-Mesa, A., & Alegre, J. (2019). Export performance in SMEs: The importance of external knowledge search strategies and absorptive capacity. Management International Review, 59, 413–437.

Fitzgerald, D. (1986). Exporting American agriculture: The Rockefeller Foundation in Mexico, 1943–1953. Social Studies of Science, 16(3), 457–483.

Gharib, M., Palm-Forster, L., Lybbert, T., & Messer, K. (In Press). Fear of fraud and willingness to pay for hybrid maize seed in Kenya. Food Policy.

Guei, R., Barra, A., & Silue, D. (2011). Promoting smallholder seed enterprises: Quality seed production of rice, maize, sorghum and millet in northern Cameroon. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 9(1), 91–99.

Hallberg, K. (2000). A market-oriented strategy for small and medium scale enterprises. Discussion Paper 40, The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Hardesty, S., & Leff, P. (2010). Determining marketing costs and returns in alternative marketing channels. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 25(1), 24–34.

Heiman, A., & Hildebrandt, L. (2018). Marketing as a risk management mechanism with application in agriculture, resources, and food management. Annual Review Resource Economics, 10(16), 1–16.

Hunter, L., & Lean, J. (2014). Investigating the role of entrepreneurial leadership and social capital in SME competitiveness in the food and drink industry. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 15(3), 179–190.

Hurley, T. M., Rao, X., & Pardey, P. G. (2014). Re-examining the Reported Rates of Return to Food and Agricultural Research and Development. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 96, 1492–1504.

ISSD. (2017). Financing seed business. IISD Africa Synthesis Paper. Wageningen, The Netherlands: ISSD. https://www.kit.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Working-Paper-Series-2017-–-3-Synthesis-paper-Financing-seed-business.pdf

Kassie, G. T., Erenstein, O., Mwangi, W., MacRobert, J., Setimela, P., & Shiferaw, B. (2013). Political and economic features of the maize seed industry in southern Africa. Agrekon, 52(2), 104–127.

Keleman, A., & Hellin, J. (2009). Specialty maize varieties in Mexico: A case study in market-driven agro-biodiversity conservation. Journal of Latin American Geography, 8(2), 147–174.

Khonje, M., Manda, J., Alene, A., & Kassie, M. (2015). Analysis of adoption and impacts of improved maize varieties in eastern Zambia. World Development, 66, 695–706.

Kersten, R., Harms, J., Liket, K., & Maas, K. (2017). Small firms, large impact? a systematic review of the SME finance literature. World Development, 97, 330–348.

Kim, N., & Shim, C. (2018). Social capital, knowledge sharing and innovation of small and medium sized enterprises in a tourism cluster. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(6), 2417–2437.