Abstract

The global food price spikes of 2007–8 and 2010 led to increased awareness of the complexity of food (in)security as a policy problem that crosscuts traditional sectoral, spatial and temporal scales. At the European Union (EU) level, this awareness resulted in calls for better integrated approaches to govern food security. This paper addresses the question of to what extent these calls were followed by an actual shift towards better integrated EU food security governance. We address this question by applying a processual policy integration framework that distinguishes four integration dimensions: (i) the policy frame, (ii) subsystem involvement, (iii) policy goals, and (iv) policy instruments. The empirical body of evidence for assessing shifts in these dimensions draws upon an extensive analysis of EU documents complemented with interview data. We find that policy integration advanced to at least some degree: the policy frame expanded towards new dimensions of food security; a wider array of subsystems started discussing food security concerns; food security goals diversified somewhat and there was an increased awareness of coherence and linkages with other issues; existing instruments, including internal procedural instruments, were expanded and made more consistent; and new types of instruments were developed. At the same time, significant differences exist between policy domains and policy integration efforts seem to have come to a halt in recent years. We conclude with various policy recommendations and suggestions for follow-up research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the 2007–8 and 2010 global food price spikes, global food security has received increasing political attention in policy arenas at the European Union (EU) level (Zahrnt 2011; Grant 2012; Kirwan et al. 2017). The food price spikes showed that states of food securityFootnote 1 are affected by a broad range of determinants and associated policies, the precise influences of which are not yet fully understood (Piesse and Thirtle 2009; Headey and Fan 2010; Rapsomanikis and Sarris 2010). Consequently, the peak of attention has been accompanied by rising awareness of the ‘crosscutting’ or ‘wicked’ problem nature of food security (Misselhorn et al. 2012; Brooks 2014; Candel 2014). At the EU level, this awareness has been reflected by two developments. First, food security concerns have been raised in a wide array of policy debates, such as those on the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), biofuels targets, and the Doha trade round negotiations. Although these debates have been characterized by a plurality of meanings attached to ‘food security’, they resulted in increased recognition of interactions between food security levels and dimensions (Candel et al. 2016). Second, as a result of this recognition, new ideas have emerged about how food security ought to be governed, including calls for more ‘coherence’ (e.g., Council of the European Union 2013; Piebalgs 2013), ‘integration’ (e.g., European Commission 2010; Red Cross EU Office 2013), and a ‘holistic’ approach (Caritas Europa 2014). These emerging governance principles led various high-level decision-makers to make pleas for a change of EU food security governanceFootnote 2:

[D]evelopment aid alone is not sufficient to effectively fight hunger. We need to look at all the available options and PCD [Policy Coherence for Development] [which is] is one critical tool to improve global food security. […] I will personally pay [a] strong attention to the impact of EU policies on the rest of the world to ensure [a] maximum coherence between its internal and development policies.

Andris Piebalgs (2013), then EU Commissioner for Development

The Council stresses that good governance for food and nutrition security at all levels is essential, and that coherence between policies should be pursued in cases of negative effects on food and nutrition security.

Council of the European Union (2013)

Despite the recognition of the need for better integrated EU food security governance, it is unclear whether an actual change of governance has occurred. This question is particularly pertinent as public policy scholars have observed that political commitments to enhanced policy integration often do not proceed beyond discursive levels (Mickwitz and Kivimaa 2007; Jacob et al. 2008; Jordan and Lenschow 2010). For that reason, this paper aims to assess to what extent political awareness of and aspirations for strengthened policy integration were accompanied by an actual change of the EU governance of food security in the aftermath of the food price spikes.

Until recently, there was no agreed-upon approach for systematically conducting such a policy integration assessment. In earlier work, we addressed this omission by developing a conceptual framework for studying policy integration(Candel and Biesbroek 2016). In this paper, to assess changes in degrees of policy integration in EU food security governance, we operationalize this framework into specific indicators and perform a quantitative content analysis of EU legislation and preparatory acts covering the period 2000–2016, as well as twenty complementary interviews with Commission officials working on food security-related issues. Importantly, we focus on EU governance of global food security, restricting the analysis to policy targeted at food security in general or in third (non-EU) countries. Although European food security has reappeared on political agendas in recent years, we have not (yet) observed explicit integrative attempts towards it as an objective.Footnote 3

The paper proceeds with setting out a policy integration framework followed by a methodological approach to the study. The results of our analysis are presented in Section 4. The paper ends with a discussion of the findings and the implications for future research and EU food security governance in Section 5.

2 A policy integration framework for assessing EU food security governance

The policy integration framework used here synthesizes insights from various fragmented literatures about integration and coordination, such as discussions of environmental policy integration (e.g., Lafferty and Hovden 2003; Jacob and Volkery 2004; Jordan and Lenschow 2010), boundary-spanning policy regimes (Jochim and May 2010), and integrated policy strategies (Rayner and Howlett 2009). The framework departs from a number of specific assumptions. First, the framework conceptualizes policy integration as a process over time (cf. United Nations 2015), rather than as a static desirable outcome or governing principle as most policy integration studies assume. Policy integration is here understood as a process of policy and institutional change and design in which actors play a pivotal role, as interactions between (political) actors constitute the mechanisms through which shifts of policy integration occur (Biesbroek and Candel 2016). Second, assessing integration is as much about increasing integration as it is about disintegration. Third, the framework consists of four distinct but connected dimensions of policy integration, which may move at different paces or even in opposite directions. These four dimensions are: (i) policy frame, (ii) subsystem involvement, (iii) policy goals, and (iv) policy instruments. A good example of a policy integration process in which these dimensions move at different paces is provided by Jacob et al. (2008), who show that although many governments have designed overarching sustainable development strategies, they often lag behind in developing supportive instrument mixes. Of course, mutual dependencies exist and interactions take place between the four dimensions of policy integration; a change in one dimension of policy integration can result in a change in another dimension. However, these influences may work in various directions and under different mechanisms that are not yet well understood.

For each of the four policy integration dimensions we distinguish between one and three specific sub-dimensions, see Table 1. The table operationalizes the sub-dimensions by setting ideal-type values (bold and italicized) that allow us to assess whether the EU governance of food security changed during and following the food price spikes (Sections 3 and 4).

The first dimension of policy integration consists of the policy frame within a governance system. Policy frame is a frequently used concept in public policy studies and generally refers to policy stakeholders’ competing or dominant problem definitions of a particular societal issue (e.g., Schön and Rein 1994; Roggeband and Verloo 2007). The framework follows a narrower interpretation by concentrating on whether a crosscutting policy problem – here food security – is recognized as such and, if so, to what extent it is perceived to require a holistic governance approach (Peters 2005). Of course, different perceptions can prevail within a governance system’s various subsystems; here it is understood as the dominant frame amongst high-level decision-makers (e.g., European Commissioners). These frames have been shown to have explanatory value over the eventual policy decisions that are made (Lau and Schlesinger 2005).

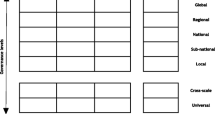

The second dimension, subsystem involvement, revolves around the range of subsystems involved in the governance of food security. Subsystems refer to relatively stable and closed configurations of actors and institutions that govern a specific policy problem or domain within a broader governance system (cf. Howlett and Ramesh 2003). Apart from subsystems that are actively involved, the dimension also includes those that are not but could be in the future because their actions affect policy outcomes (Dupuis and Biesbroek 2013). The degree of subsystem involvement is thus relative to the number of potentially relevant subsystems for food security. Additionally, this dimension also covers the density of interactions between subsystems in food security. The assumption is that higher amounts of policy integration are characterized by a number of subsystems that frequently interact with each other and that maintain relatively more infrequent interactions with a wider set of ‘loosely coupled’ subsystems (cf. Orton and Weick 1990). As argued in the introduction, food security’s many levels and dimensions make them a potentially broad range of EU subsystems, which could be involved in its governance, see Table 1.

The dimension policy goals refers to: (i) the range of policies across subsystems in which (concerns about) food security are explicitly adopted as a goal, and (ii) the coherence between these goals. These goals are pursued through a mix of policy instruments, which constitutes the fourth dimension. Policy instruments can be deployed within subsystem policy efforts, but also at the level of the governance system, for example in the case of interdepartmental working groups. We make a distinction between substantive and procedural policy instruments. Substantive instruments allocate (financial, informational, regulative or organizational) resources to directly affect the ‘nature, types, quantities and distribution of the goods and services provided in society’ (Howlett 2000: 415); procedural instruments are designed to ‘indirectly affect outcomes through the manipulation of policy processes’ (ibid.: 413), e.g., through the creation of new institutions. This dimensions encompasses three sub-dimensions: (i) the range of policies that adopt or adjust policy instruments to address food security concerns, (ii) the deployment of procedural instruments to facilitate coordination between subsystems, and (iii) the consistency of the policy instrument mix as a whole. An important further distinction for the first sub-dimension is between policy instruments that are explicitly targeted at food security concerns, e.g., development cooperation or research programs, and instruments that are adjusted to accommodate such concerns without necessarily being framed in terms of food security (cf. Dupuis and Biesbroek 2013).

3 Methodological approach

To study the development of policy integration in the EU governance of food security, we operationalized each of the four dimensions into specific indicators. Our primary source of data for studying these indicators were EU documents, which we retrieved by systematically searching the EU online search engines (for search criteria, see Online Resource (OR) I). Subsequently, data was coded by using the coding program Atlas.ti, resulting in the data extraction tables and figures presented in Section 4 and OR III. Table 2 presents the specific indicators and modes of data collection and analysis for each of the four dimensions. The analysis covers the period from 2000 through 2016, which allows comparison of the governance of food security in the period before the food price spikes (up to mid-2007) with that in the period of the spikes (2007–10) and post-spikes (2011–16). The analysis was performed by comparing the different sources of extracted data with the dimensions’ ideal-type manifestations in Table 1. Importantly, we included (sections of) documents referring to global food security and food security in general; references with an explicit focus on European food security were excluded.

As information and documents about the internal EU policy process are difficult to systematically access and analyse, we used publicly available proxy data for most dimensions. Limited access to quantifiable data also forced us to complement the dimension of (procedural) policy instruments with qualitative data collected through interviews with twenty senior policymakers involved in the EU governance of food security. Interview data were collected in Spring 2014, coded and analyzed, see Candel et al. (2016).Footnote 4 Furthermore, because the operationalization and measurement of policy coherence and consistency is understudied at best and highly controversial at worst (Nilsson et al. 2012), these were not measured directly. Instead, they were included by looking for explicit references to linkages among goals and instruments.

It should be noted that we studied the development of policy integration by focusing on the number and types of goals and instruments, without differentiating on quality or potential impact of specific goals and instruments. Hence, our findings only allow us to make statements about how policy integration within the policy process advanced, not about the success of these more or less integrated policy processes in addressing levels or dimensions of food security. This is further reflected on in Section 6. In addition, most indicators consist of explicit references to food security (or similar concepts). The analysis of policy goals and instruments that were adjusted to accommodate food security concerns without explicitly referring to these is very challenging as virtually all policies may be argued to affect or accommodate food security to some extent, resulting in a dependent variable problem (cf. Dupuis and Biesbroek 2013). To overcome this challenge we used the proxy that food security concerns should at the least be mentioned in preparatory acts (which discuss the underlying rationales of proposed changes) or be put forward by interviewees as playing an important role in order to conclude that at least some level of integration occurred.

4 Results: Policy integration in the EU governance of food security

This section presents the main findings of the analysis. Each subsection first summarizes the main findings for the dimension, followed by a more detailed presentation of the results.

4.1 Policy frame

The policy frame was studied by analyzing the amount and content of attention to food security in European Commissioners’ speeches. In summary, the results show that food security became increasingly perceived as a multi-dimensional issue (or a problem deserving attention in the first place) but it goes too far to speak of a shared or comprehensive policy frame, as linkages between policy efforts and associated effects on different dimensions and levels of food security remained largely unspoken or implicit. Moreover, food security continued to be primarily framed in the context of external assistance; aspects related to access, (global) health, or environmental sustainability, remained largely untouched. Recent years have shown a steep drop in the number of Commissioners referring to food security.

Looking more closely at the findings, Fig. 1 shows that the overall number of references to food (in)security in Commissioners’ speeches increased considerably during the first food price spike of 2007–8 and especially in the years following the second price spike of 2010. On the contrary, the years immediately preceding the spikes were characterized by very little high-level attention to food security. What is more, the figure shows that this increase can be largely explained through the increase of attention from ‘new’ policy domains. Whereas before, the spikes' most attention originated from the ‘traditional’ directorate-generals (DGs) of Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid and, to a lesser extent, Agriculture; these were complemented with the Commission’s presidency and the DGs of Science and Research and Environment in later years. However, after the ‘peak year’ 2013, attention dropped again to levels similar or lower than prior to the spikes. For the years 2015–16 only one speech with references to food (in)security was found (by Commissioner Hogan of Agriculture).

In terms of the content of references to food security, we found a diversification from an almost entire focus on external assistance and some multilateral trade considerations in the early 2000s towards the inclusion of global food security as a function of (European) agriculture, climate change and environmental concerns, scientific cooperation and research, and global governance. Thus, food security not only attracted attention from a broader range of domains, but was also considered from a broader perspective by the Commission as a whole, including the presidency. Relatively few explicit references were made to the need for integrative policy or linkages between policy domains. In cases where reference was made, this related mainly to the need for aligning development efforts with humanitarian aid and, to a lesser extent, to other domains. The Commission’s Policy Coherence for Development program, for example, was only mentioned rarely.

When it comes to the individual EU policy domains, some interesting observations about the quantity and content of food (in)security can be made. To start with Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Affairs, the Commissioner(s) of which made most references during the period of analysis, a clear increase of attention can be observed in the period 2010–13. This spike of attention can partially be explained by the separation of the DG into two new DGs, one for Development Cooperation and the other for Humanitarian Aid. Commissioners Michel and De Gucht, who led the DG just before and during the first price spike, paid hardly any attention to the issue (at least in their speeches). Explicit consideration of the need for coherence or coordination was clearest under Commissioner Nielson (2000–4), though subsequent Commissioners continued subscribing to the importance of aligning short-term humanitarian aid and longer-term development assistance. In addition, Commissioner Piebalgs (2010–14) regularly linked food security to concerns about climate change and environmental degradation around the Rio + 20 Sustainable Development conference in 2012.

Commissioners of Agriculture also paid attention to food security over the whole period of analysis, whereby Commissioners Fischler (2000–4) and Fischer Boel (2004–9) touched upon the topic more often than Commissioner Cioloş (2010–14). All Commissioners invoked food security particularly in the context of the Common Agricultural Policy and in food security exemption clauses in (agricultural) trade agreements. A recurring argument in these speeches was that a productive (European) agriculture and agricultural trade are key to eradicating hunger across the world. Commissioner Fischler already underlined the need for policy coherence to some extent; Cioloş did so less explicitly, but repeatedly stressed the food security linkages between agriculture and environmental sustainability, research and innovation, and trade. In more recent years, Commissioner Hogan (2014-present) has been the only Commissioner of the Juncker Commission who referred to food security in one of his speeches. Fisheries was touched upon only very infrequently across the whole period.

Two domains to which the Commissioners paid increasing attention to food security after the food price spikes were Research and Environment. For Research this was due to the various food security research calls and programs as well as the emphasis on international scientific cooperation to address food insecurity. For Environment, Commissioner Potočnik (2010–14) started referring to food security in the context of the Rio + 20 conference and in relation to agriculture’s effects on the global long-term potential to produce food. Our findings also show increased attention of the Commission’s presidency after president Prodi (1999–2004) was succeeded by Barroso (2004–14), and within the Barroso presidency during and following the food price spikes. This suggests that the presidency and Secretariat-General came to view food security as a relatively more important EU concern after the spikes. Barroso particularly referred to food security as an important global challenge and priority for EU development assistance, while also making links with other terrains, such as biofuels, fisheries, climate change, environmental degradation, science, and agriculture. Juncker (2014-present) did not refer to food security in any speech.

Trade and External Relations are two domains in which the Commissioners regularly touched upon food security over the whole period, but where attention was more frequent before compared to during and after the food price spikes. The Commissioners of Trade made these references primarily in the context of exemption clauses on food security in trade agreements and with respect to the importance of agriculture. The Commissioners and High Representative of External Relations mainly referred to existing assistance programs.

In addition to these domains, there are a number of domains in which the Commissioners referred to food security only a couple of times, the most notable being Inter-Institutional Relations under Commissioner Wallström (2004–9), who repeatedly stressed the role of women for (global) food security. For some domains, Commissioners started mentioning food security only during and after the food price spikes, but did so (very) infrequently.

4.2 Subsystem involvement

By analyzing the policy preparation by EP committees and the Commission’s DGs, we were able to assess the involvement of different subsystems in food security governance over time. In summary, our findings show that before the food price spikes, the subsystem Development was clearly the most dominant subsystem in the EU governance of food security. Other subsystems only made infrequent references to food security. During and after the food price spikes, and particularly after the spike of 2010, ‘new’ subsystems became involved more structurally, particularly the External Affairs, Agriculture, Trade, and Environment subsystems. In recent years, the level of subsystem involvement dropped and Development came to play a relatively larger role again.

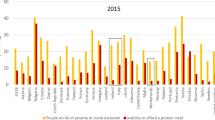

Looking more closely at the results, they show both an increase and diversification of references to food security across committees in the EP, see Fig. 2. Before 2008, only the Committee on Development frequently addressed food security. All other committees invoking food security, such as those on Foreign Affairs, Environment, and Agriculture, did so fewer than 5 times per year. From 2008 onwards, more committees started referring to global food security (concerns) on a regular basis, including the committees on Agriculture and Rural Development, Environment and International Trade. The year 2013 shows a clear peak in the number of references. Part of this peak can be explained by an increase in the number of references by the ‘traditional’ Committee on Development, but most of the increase follows from the involvement of new subsystems. The years 2009 and 2014 are remarkable for their relatively low numbers of referrals, which could be explained by the EP elections held in these years. Involvement continued to be low in 2015, but increased again in 2016.

In terms of the interactions between subsystems, Fig. 3a-d show that in the years during and following the food price spikes the constellation of parliamentary committees developed into a relatively more complex network. Whereas in the years up to 2007, the Committee on Development was the dominant subsystem with no or hardly any interactions with other subsystems, a whole range of committees became involved in the seventh term of the EP. Most of these newly involved committees primarily interacted about food security with the Committee on Development (except for the Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development). Many of these interactions diminished again in the 8th term of the EP.

Subsystems interactions in the European Parliament (DEVE = Committee on Development; ITRE = Committee on Industry, Research and Energy; AGRI = Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development; ENVI = Committee on Environment; INTA = Committee on International Trade; PECH = Committee on Fisheries; AFET = Committee on Foreign Affairs; BUDG = Committee on Budgets; FEMM = Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality.). (Interactions between committees are indicated in the figure when committees interacted at least four times with each other in a parliamentary term (or two times for the first half of the current term 2014–2016). The direction of the arrows indicates which of the interacting committees is the opinion-giver)

Similar patterns can be observed when looking at the directorate-generals of the Commission. Figure 4 shows an increase in references to food security in COM-documents, particularly in the years following the 2010 food price spike. Here too, diversification toward new domains is visible, albeit to fewer than in the case of the EP, and at a later stage.Footnote 5 The results show that the increase in references is almost exclusively the result of ‘new’ DGs starting to invoke food security, whereas references by DG Development, even in combination with DG Humanitarian Affairs and Civil Protection, remained at roughly the same level. Two DGs that became particularly active were DG Agriculture and Rural Development and the European External Action Service (EEAS). For DG Agri this was primarily related to the CAP reform (and its interactions with global food security), whereas most references by the EEAS were made in the context of foreign affairs and international cooperation. Apart from these DGs, the group “Other” is relatively big, both before and after the spikes. This indicates that there was a whole range of DGs that infrequently mentioned food (in)security concerns. Here too, the number of references decreased in 2015 and increased again in 2016.

4.3 Policy goals

Online Resource III (Table 2) provides an overview of the policies and programs that explicitly mentioned food security as one of their policy goals. In summary, our findings show that the inclusion of food security policy goals cautiously diversified across ‘new’ policies from the 2007–8 food price crisis onwards. A parallel development is the increase in notions of coherence of policy goals. However, policy goals were often restricted to incidental issues and concerns and did not include all potentially relevant domains.

Looking more closely at the results shows that before 2010 almost all key policies were related to development cooperation, humanitarian aid, and external assistance to neighbouring or partner countries and regions. A major policy in this respect was the 2008–10 Food Facility,Footnote 6 which was set up to help countries and populations adapt to spiking food prices. Although food security goals were linked to a wide array of concerns, such as water, climate and health, this was principally done in the context of external assistance. Two exceptions to this observation were several bans on the import of various fish species,Footnote 7 which were justified by the argument that they were important for global food security, and the Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources intended to safeguard future food security.Footnote 8 Additionally, food security clauses were included in a number of trade and fisheries treaties.

From 2010 onwards, food security policy goals were defined and included in a wide array of other policy processes, most notably the CAP and the Common Fisheries Policy,Footnote 9 soilFootnote 10 and bio-economyFootnote 11 strategies, the Horizon2020 research framework,Footnote 12 and the Novel Foods regulation.Footnote 13 Combined with additional development and humanitarian aid goals, this resulted in an overall increase of the number of policies with food security as an objective. It is important to note that for several of these ‘new’ policies, such as the CAP, (global) food security was mentioned as a policy goal in soft laws, green and white papers, but did not recur as such in final legislation.

Before 2007–8 notions of the coherence and coordination of policy goals in hard and soft laws were mostly restricted to the mutual coherence of development aid instruments and to attuning development and humanitarian aid efforts. From then onwards, references to coherence of policy goals increased and food security concerns came to be linked, albeit incidentally, to a more varied range of issues, such as the development of biofuels, health, climate change, and trade.

4.4 Policy instruments

Online Resource III (Table 4) provides an overview of instruments that were linked to food security (concerns). The analysis of soft and hard legislation combined with interviews with Commission staff show that since the outbreak of the food price spikes, ‘traditional’ food security instrument mixes were expanded, made more consistent, and complemented with some new types of instruments. In addition, the coordination and consistency of instruments were increasingly facilitated within the Commission, most notably by impact assessments, inter-service consultations, and Policy Coherence for Development (PCD). Many subsystems outside of external assistance directed no or only limited instruments explicitly at pursuing food security objectives, but may have adjusted existing instruments to accommodate food security concerns (see Section 5).

The most substantial instruments explicitly targeting global food security before the spikes were the provision of food aid and actions supported through the food security program, both embedded in the 1996 regulation on food aid policy and special operations in support of food security. As of 2007, this regulation was adopted within the Financing Instrument for Development Cooperation,Footnote 14 which merged various geographic and thematic development instruments into a single development instrument. Another key instrument is the European Development Fund, which has been the main cooperation instrument for ACP-countries (African, Caribbean, and Pacific Group of States) and Overseas Countries and Territories. Similarly, various neighborhood assistance instruments, such as TACIS (Technical Aid to the Commonwealth of Independent StatesFootnote 15) and MEDA (Euro-Mediterranean PartnershipFootnote 16), were used to provide assistance to countries and regions neighbouring the EU. More specific instruments that were already used before the spikes were the Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural Development (CTA), several bans on the import of particular fish species, and efforts to fix export refunds; all of which were explicitly linked to global food security concerns.

Most of these instruments continued to exist during and after the spikes, sometimes in a different or expanded form. A major expansion of food security efforts in development cooperation was realized by the temporary Food Facility,Footnote 17 which was created to help countries and regions become more resilient. Although we did not observe a full reconsideration and alignment of instruments, in some sectors instruments were combined or adapted in more consistent instrument mixes, such as the previously mentioned Financing Instrument for Development Cooperation and the new European Neighbourhood (and Partnership) Instrument. In addition, new instruments were developed and food security concerns became embedded in instruments that were previously not explicitly targeted at food security, for example the Instrument for StabilityFootnote 18 (later: Instrument contributing to stability and peace) used to provide external assistance in cases of political instability or major disasters. This instrument replaced the previous Rapid Response Mechanism,Footnote 19 which, although it may have contributed to food security, did not explicitly take food security concerns into account.

A number of new instruments linked to food security originated from subsystems other than development cooperation and external assistance. Examples hereof are the prominent position of food security within the Horizon2020 research framework,Footnote 20 including the Joint Research Centre’s activities on food security, monitoring the impact of biofuels,Footnote 21 and the Copernicus Earth Observation program.Footnote 22 The EU also appointed a special representative to the African Union.Footnote 23 For many of the subsystems and policy goals identified in the previous two sections we found either no or only minor associated substantive instruments. For example, the final versions of the Common Agricultural PolicyFootnote 24 and the Common Fisheries PolicyFootnote 25 did not contain any instruments explicitly linked to food security concerns. This either means that policy instruments were adjusted without labelling them in terms of food security or that food security concerns mentioned in preparatory acts (soft law) were not followed by policy change (see Section 5 for a further discussion).

The findings from the policy analysis are supported by our interview data. Regarding the EU’s internal procedural instruments in the governance of food security, interviews with Commission officials revealed that quite a number of instruments had been used to ensure and enhance coordination and coherence within the Commission. Although interviews were only held in 2014, respondents indicated that these instruments had become more important in recent years. Two of the Commission’s most common internal procedural instruments, impact assessments and inter-service consultations, were reported to be important tools for addressing food security-related concerns, for example in biofuels policy, the Common Agricultural Policy, and trade agreements. In practice, these concerns were raised mainly by officials working in the domains of development cooperation and external assistance. Another key instrument in this respect is Policy Coherence for Development, with food security as one of its five key priorities. PCD enables DG Development to screen the Commission’s work program for initiatives that may have an impact on food security and, consequentially, to have a say in the policy process regarding a broad range of issues. However, respondents argued that because of the limited capacity of the PCD team, efforts were limited to major policies and programs that might have a detrimental effect on food security, such as the Common Agricultural Policy and trade agreements:

In the past there were moments where I was alone on the file, on PCD coordination, and at that moment we just focused on the big priorities, on things that are burning. So it all depends on the staff situation. ... We always say to people up in the hierarchy that we can use more people; if they give us twenty we could use them all, then we would expand the number of priorities that we are able to follow.

Policy officer from DG DEVCO

PCD is therefore still primarily used according to the ‘do-no-harm’ principle, rather than to realize synergies. In addition, respondents indicated that when it comes to the crunch, other objectives were generally given priority over food security concerns. One policy officer indicated that the EU’s economic and political crisis did not make things easier in this regard, though at the same time nuanced apparent trade-offs:

Life for PCD was easier when we were in a situation of prosperity. Of course, if you have a crisis and European jobs and the prosperity of the EU on the line, and the policy trade-off is presented in a way where you have to choose between the European poor and people in the other countries that are not European voters... ... But part of my job is also to explain that the equation is not always that simple. It’s not usually one against the other. It’s also our job to try to bring in the narrative, explain why dealing with development and food security is important in the long term for Europe.

Policy officer from DG DEVCO

Three other types of instruments that respondents mentioned to be relevant were: i) foresight studies performed by the Commission’s Joint Research Centre, which help put food security on the agendas of various services and provide scenarios for courses of action, ii) the Commission’s staff mobility policy, which facilitates a circulation of perspectives and expertise, and iii) the creation of ‘boundary units’, i.e. units created to address external concerns within a domain, e.g. the unit ‘ACP, South Africa, FAO and G8/G20’ within DG AGRI.

5 Discussion

5.1 Synthesis of our findings

Our findings suggest that each of the policy integration dimensions in the EU governance of food security advanced to at least some degree in the aftermath of the food price spikes. The policy frame expanded towards new dimensions of food security and ideas about how it should be addressed; a wider array of subsystems started discussing food security concerns; food security goals diversified somewhat and there was an increased awareness of coherence and linkages with other issues; existing instruments, including internal procedural instruments, were expanded and made more consistent; and new types of instruments were developed. Whereas food security remained an important issue in development cooperation, it also spread to new domains and policy debates, such as those on agriculture, biofuels, environmental programs, and trade. Policy changes that are particularly notable are the substantial resources made available to food security research under the Horizon2020 program and the adjustment of biofuels targets resulting from concerns about indirect land use changes. At the same time, policy integration proved more substantial in some dimensions than in others. There are three findings that make us answer our initial question of whether actions speak louder than words with a ‘partly’.

First, we found that the increase of awareness in various ‘newer’ subsystems did not seem to result in actual policy changes. This is clearest for the most recent reforms of the CAP and the CFP: although food security concerns were pervasive, it is doubtful whether these truly affected final outcomes (Zahrnt 2011; Candel 2016). Both preparatory and final acts did not mention any changes of specific goals and instruments, but were restricted to generic references to global food security as an important objective. This seems to suggest that food security concerns were primarily used to strengthen the legitimacy of existing or proposed policy directions. This (cautious) conclusion corresponds with insights shared by our interviewees. In the case of the CAP, respondents claimed that food security primarily served as a ‘buzzword’ for enhancing the legitimacy of policy proposals as it proved to resonate with a wide array of stakeholders (Candel et al. 2016). Of course, this does not mean that these policies may not make a contribution to global food security (although critical voices exist too, e.g., Brooks 2014; Boysen et al. 2015); however, we did not find a change or explicit (re)targeting following on the renaissance of food security concerns. It is important to note that such discursive or symbolic processes of policy integration are not necessarily an undesired development (cf. Edelman 1985). Symbolic integration can play an important agenda-setting role in the sense that it draws subsystems’ attention to particular food security concerns. Such awareness is a prerequisite for more substantive governance changes to occur.

Second and building on the last point, although we observed increasing awareness of interactions across the different drivers of food security as well as pleas for enhanced policy coherence, policy efforts were largely limited to mitigating the most obvious externalities. It is true that a number of development-, humanitarian aid-, and neighbourhood-related food security instruments were merged into more consistent instruments, but few attempts were made at realizing further synergies, e.g., by moving towards an overarching cross-sectoral global food security strategy and instrument mix. Limited PCD capacities and resources play a role here, but may in themselves result from insufficient political commitment (cf. Harris et al. 2017). In addition, not all subsystems that could play a role in governing global food security (Section 2) did so explicitly.

Third, findings for the most recent years (2014–16) seem to indicate a decrease of attention to global food security again: references to food security have been almost absent in Commissioners’ speeches under the Juncker presidency, while subsystem involvement was much lower, particularly in 2014–15. Although 2016 saw an increase of subsystem involvement in the Commission and Parliament again, the lack of high-level prioritization makes further policy integration of goals and instruments unlikely in the near future.

5.2 Follow-up questions

Undeniably, the relationship between strengthened policy integration in governance processes and eventual food security outcomes remains understudied and therefore unclear. Although policy integration scholars assume that more integration would result in better outcomes, studying such impacts is both a conceptual and methodological challenge (Jordan and Lenschow 2010). We consider overcoming these challenges through conceptual and methodological innovation as a vital next step in future research on integrative food security approaches (cf. Knill and Tosun 2012).

Another important topic for follow-up research considers the “why”-question behind our analysis; why did the EU governance of food security advance quite significantly in some domains but not in others? Although providing very little insights into what explains successful explanation (Peters 2015), the literature provides various possible explanations for the latter question (for overviews, see: Peters 2015; Vince 2015; Candel 2017b). First, pre-existing policy elements, such as instruments, institutions or capacities, often prove remarkably resilient as a result of lock-in effects following from path-dependent processes of policy layering (Pierson 2000; Rayner and Howlett 2009). Second, food security may have been replaced on the political agenda by competing issues that are perceived as more pressing, hence reducing the political pressure to invest in policy integration efforts (cf. Downs 1972). In this respect, it would be worthwhile looking into possible trade-offs resulting from efforts to govern food security and various other crosscutting policy problems – including climate change, immigration, terrorism, and the stability of financial systems – at the same time. Not only do higher degrees of integration require more resources, including institutional capacity, that cannot be used elsewhere, but a focus on the coherence of goals and the consistency of instruments with respect to food security may diminish the coherence and consistency of the governance of other issues (Adelle et al. 2009; Lagreid and Rykkja 2015). These are everyday choices in the working practice of decision-makers. Third, integration is simply no easy task, and many examples of failure exist (6, Perri 2004). As politicians are known to avoid risk (Hood 2010), it is unlikely that they will invest serious time and resources in policy integration (Howlett 2014). Fourth, for some policymakers the invocation of food security concerns or calls for integration may have merely served the purpose of window dressing, enhancing the legitimization of a specific policy proposal or direction while lacking the accompanying political will or resources (Mickwitz and Kivimaa 2007). Various scholars and commentators have argued that the latter has been the case with food security’s pervasiveness in global policy debates in recent years. According to some particularly critical scholars, invoking ‘food security’ merely suits proponents of intensifying food production (Fish et al. 2013; Rosin 2013; Tomlinson 2013) or of a neoliberal trade agenda (Jarosz 2011; Koc 2013). Our results do not support these claims for policymaking at the EU level, although strategic considerations certainly seemed to have played a role in the renaissance of food security discourse.

5.3 Implications for governance

Our results allow for concrete recommendations on how the EU governance of food security could be advanced further. As Table 1 elaborates, full policy integration into food security governance would implicate the involvement of all possibly relevant subsystems. Subsystems would then need to get involved beyond ‘do-no-harm’, aiming to create synergies between policy efforts. In addition, full integration would require the design and implementation of an overarching EU strategy, which elaborates the role of each of these subsystems in addressing food security, thereby ensuring the coherence of policy efforts. The PCD commitment to food security would be a good starting point for doing so, but would have to be extended from development cooperation to other fields of EU policymaking. Such an extension would require coordinative policy instruments at the system-level. These coordinative instruments do not necessarily have to be created anew; existing coordinating entities, such as the Secretariat-General in the Commission, could serve as boundary-spanning structures that take the lead in developing a holistic approach and facilitating coordination between subsystems (cf. Hartlapp et al. 2012; Kassim et al. 2013; Candel et al. 2016). The consistency of subsystems’ instrument mixes is a key challenge in realizing such a boundary-spanning policy regime.

An important question is whether further policy integration is politically feasible or desirable in the current political landscape (cf. Jordan and Halpin 2006). Member states have been reluctant to hand over jurisdictions to the EU institutions, especially regarding domains related to external affairs and issues for which the EU has no formal competence This has been reinforced by the rise of Euroscepticism over the last years. It may therefore be more realistic to strive for the optimization of lower degrees of policy integration, for example by attempting to reduce the clearest externalities (Candel 2016). Although high policy integration ambitions help picturing the desired path forwards, in the short-term it may be more productive to harvest the low-hanging fruit to ensure that actions do speak louder than words.

Notes

We follow the FAO (1996) definition of food security as ‘all people, at all times, having physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.’

The EU governance of food security is here understood as all policy efforts at the EU level that either positively or negatively affect food security outcomes, i.e. food availability, access, utilization, and stability.

For this study, 20 Commission officials were interviewed in Spring 2014 about whether and how the Commission is capable of dealing with the ‘wickedness’ of food security. Respondents worked in a range of directorate-generals and thus dealt with a variety of food security levels and dimensions. See the original paper for more information about the scope of this study and the selection criteria that were used.

Note that because of the lower overall number of references, Figure 4 mentions those DGs that refer to FS 4 (instead of 5) or more times in a year.

Regulation 1337/2008

e.g., Regulations 826/2004, 827/2004, and 828/2004

Decision 869/2004

Regulation 1380/2013

COM 46/2012

COM 60/2012

Regulation 1291/2013; Decision 743/2013

Regulation 2283/2015

Regulation 1905/2006

Regulation 99/2000

Regulation 1488/1996

Regulation 1337/2008

Regulation 1717/2006

Regulation 381/2001

Regulation 1291/2013; Decision 743/2013

Regulation 597/2009

COM 312/2013

Decision 805/2007

(Regulations 1305/2013, 1306/2013, 1307/2013, and 1308/2013)

Regulation 1380/2013

References

6, Perri. (2004). Joined-up government in the western world in comparative perspective: a preliminary literature review and exploration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 14(1), 103–138.

Adelle, C., Pallemaerts, M., & Chiavari, J. (2009). Climate change and energy security in Europe: Policy integration and its limits. Stockholm: Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies.

Biesbroek, G. R., & Candel, J. J. L. (2016). Explanatory mechanisms for policy (dis)integration: climate change adapation policy and food policy in the Netherlands. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the European Group for Public Administration (EGPA), Utrecht, 24–26 August.

Boysen, O., Hans G. J., and Alan M. (2016). "Impact of EU agricultural policy on developing countries: A Uganda case study." The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 25(3), 377-40.

Brooks, J. (2014). Policy coherence and food security: The effects of OECD countries’ agricultural policies. Food Policy, 44, 88–94.

Candel, J. J. L. (2014). Food security governance: a systematic literature review. Food Security, 6(4), 585–601.

Candel, J. J. L. (2016). Putting food on the table: The European Union governance of the wicked problem of food security. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

Candel, J. J. L. (2017a). Diagnosing integrated food security strategies. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2017.07.001, https://ac.els-cdn.com/S1573521417300076/1-s2.0-S1573521417300076-main.pdf?_tid=e6d5962a-d41a-11e7-8813-00000aab0f6b&acdnat=1511859946_80e2a7a73323068584202824a466c7b5

Candel, J.J.L. (2017). "Holy Grail or inflated expectations? The success and failure of integrated policy strategies." Policy Studies, 38(6):519-552.

Candel, J. J. L., & Biesbroek, G. R. (2016). Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sciences, 49(3), 211–231.

Candel, J. J. L., Breeman, G. E., & Termeer, C. J. A. M. (2016). The European Commission's ability to deal with wicked problems: an in-depth case study of the governance of food security. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(6), 789–813.

Caritas Europa. (2014). The EU's role to end hunger by 2025. Brussels: Caritas Europa.

Council of the European Union. (2013). Council conclusions on food and nutrition security in external assistance. Brussels: Council of the European Union.

Downs, A. (1972). Up and down with ecology - the 'Issue-attention cycle. The Public Interest, 28, 38–50.

Dupuis, J., & Biesbroek, R. (2013). Comparing apples and oranges: The dependent variable problem in comparing and evaluating climate change adaptation policies. Global Environmental Change, 23(6), 1476–1487.

Edelman, M. J. (1985). The symbolic uses of politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

EESC (2016). Opinion of the European economic and social committee on more sustainable food systems. Brussels: European Economic and Social Commitee.

European Commission (2010). An EU policy framework to assist developing countries in addressing food security challenges, 31 March, COM (2010) 127. Brussels: European Commission.

FAO (1996). Rome declaration on world food security. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Fish, R., Lobley, M., & Winter, M. (2013). A license to produce? Farmer interpretations of the new food security agenda. Journal of Rural Studies, 29, 40–49.

Fresco, L. O., & Poppe, K. J. (2016). Towards a common agricultural and food policy. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

Grant, W. (2012). Economic patriotism in European agriculture. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(3), 420–434.

Harris, J., Drimie, S., Roopnaraine, T., & Covic, N. (2017). From coherence towards commitment: Changes and challenges in Zambia's nutrition policy environment. Global Food Security, 13, 49–56.

Hartlapp, M., Metz, J., & Rauh, C. (2012). Linking agenda setting to coordination structures: bureaucratic politics inside the European Commission. Journal of European Integration, 35(4), 425–441.

Headey, D., & Fan, S. (2010). Reflections on the global food crisis—how did it happen? How has it hurt? And how can we prevent the next one? IFPRI Research Monography 165. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Hood, C. (2010). The blame game: Spin, bureaucracy, and self-preservation in government. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Howlett, M. (2000). Managing the “hollow state”: procedural policy instruments and modern governance. Canadian Public Administration, 43(4), 412–431.

Howlett, M. (2014). Why are policy innovations rare and so often negative? Blame avoidance and problem denial in climate change policy-making. Global Environmental Change, 29, 395–403.

Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2003). Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems (2nd ed.). Don Mills: Oxford University Press.

iPES Food (2016). Why we need a common food policy for the EU: an open letter to Mr Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission.

Jacob, K., & Volkery, A. (2004). Institutions and instruments for government self-regulation: Environmental policy integration in a cross-country perspective. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 6(3), 291–309.

Jacob, K., Volkery, A., & Lenschow, A. (2008). Instruments for environmental policy integration in 30 OECD countries. In A. Jordan & A. Lenschow (Eds.), Innovation in environmental policy? Integrating the environment for sustainability (pp. 24–48). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Jarosz, L. (2011). Defining world hunger: Scale and neoliberal ideology in international food security policy discourse. Food, Culture and Society, 14(1), 117–139.

Jochim, A. E., & May, P. J. (2010). Beyond subsystems: policy regimes and governance. Policy Studies Journal, 38(2), 303–327.

Jordan, G., & Halpin, D. (2006). The political costs of policy coherence: Constructing a rural policy for Scotland. Journal of Public Policy, 26(1), 21–41.

Jordan, A., & Lenschow, A. (2010). Policy paper environmental policy integration: a state of the art review. Environmental Policy and Governance, 20(3), 147–158.

Kassim, H., Peterson, J., Bauer, M. W., Connolly, S., Dehousse, R., Hooghe, L., et al. (2013). The European Commission of the twenty-first century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kirwan, J., Maye, D., & Brunori, G. (2017). Acknowledging complexity in food supply chains when assessing their performance and sustainability. Journal of Rural Studies, 52, 21–32.

Knill, C., & Tosun, J. (2012). Public policy: A new introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Koc, M. (2013). Discourses of food security. In B. Karaagac (Ed.), Accumulations, crises, struggles: Capital and labour in contemporary capitalism (pp. 245–265). Berlin: LIT Verlag.

Lafferty, W., & Hovden, E. (2003). Environmental policy integration: Towards an analytical framework. Environmental Politics, 12(3), 1–22.

Lagreid, P., & Rykkja, L. H. (2015). Organizing for “wicked problems” – analyzing coordination arrangements in two policy areas: Internal security and the welfare administration. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 28(6), 475–493.

Lau, R. R., & Schlesinger, M. (2005). Policy frames, metaphorical reasoning, and support for public policies. Political Psychology, 26(1), 77–114.

Mickwitz, P., & Kivimaa, P. (2007). Evaluating policy integration: the case of policies for environmentally friendlier technological innovations. Evaluation, 13(1), 68–86.

Misselhorn, A., Aggarwal, P., Ericksen, P., Gregory, P., Horn-Phathanothai, L., Ingram, J., et al. (2012). A vision for attaining food security. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4(1), 7–17.

Nilsson, M., Zamparutti, T., Petersen, J. E., Nykvist, B., Rudberg, P., & McGuinn, J. (2012). Understanding policy coherence: analytical framework and examples of sector–environment policy interactions in the EU. Environmental Policy and Governance, 22(6), 395–423.

Orton, J. D., & Weick, K. E. (1990). Loosely coupled systems: a reconceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 15(2), 203–223.

Peters, B. G. (2005). The search for coordination and coherence in public policy: Return to the center? Unpublished paper. Pittsburgh: Department of Political Science, University of Pittsburgh.

Peters, B. G. (2015). Pursuing horizontal management: The politics of public sector coordination. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Piebalgs, A. (2013). Stepping-up coherence between EU policies to improve food security, speech at an OECD Side-Event on Shaping Coherent and Collective Action in a post-2015 World. http://eu-un.europa.eu/articles/fr/article_13981_fr.htm. Accessed 3 November 2014.

Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267.

Piesse, J., & Thirtle, C. (2009). Three bubbles and a panic: An explanatory review of recent food commodity price events. Food Policy, 34(2), 119–129.

Rapsomanikis, G., & Sarris, A. (2010). Commodity market review. Rome: FAO.

Rayner, J., & Howlett, M. (2009). Introduction: Understanding integrated policy strategies and their evolution. Policy and Society, 28(2), 99–109.

Red Cross EU Office (2013). Nutrition EU Policy Framework. http://www.redcross.eu/en/What-we-do/Development-Aid/Food-Security/Nutrition-Eu-Policy-Framework/. Accessed 3 Nov 2014.

Roggeband, C., & Verloo, M. (2007). Dutch women are liberated, migrant women are a problem: the evolution of policy frames on gender and migration in the Netherlands, 1995–2005. Social Policy & Administration, 41(3), 271–288.

Rosin, C. (2013). Food security and the justification of productivism in New Zealand. Journal of Rural Studies, 29, 50–58.

Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 303–326.

Schön, D. A., & Rein, M. (1994). Frame reflection. Towards the resolution of intractable policy controversies. New York: Basic Books.

Tomlinson, I. (2013). Doubling food production to feed the 9 billion: A critical perspective on a key discourse of food security in the UK. Journal of Rural Studies, 29, 81–90.

United Nations (2015). Policy integration in government in pursuit of the sustainable development goals: Report of the expert group meeting held on 28 and 29 January 2015 at United Nations Headquarters, New York: United Nations.

Vince, J. (2015). Integrated policy approaches and policy failure: the case of Australia’s oceans policy. Policy Sciences, 48(2), 159–180.

Zahrnt, V. (2011). Food security and the EU’s common agricultural policy: Facts against fears. Brussels: ECIPE.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2nd International Conference on Public Policy in Milan, 1-4 July 2015, and at the 9th General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research in Montréal, 27-29 August 2015. We would like to thank Katrien Termeer, Arild Aurvåg Farsund, Carsten Daugbjerg, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on previous drafts of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Candel, J.J.L., Biesbroek, R. Policy integration in the EU governance of global food security. Food Sec. 10, 195–209 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-017-0752-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-017-0752-5