Abstract

Pseudocricetodontines from the late Eocene and early Oligocene of south-east Serbia are described. The Pseudocricetodontinae is a clade with a Eurasian geographical range during most of the Oligocene. The subfamily and genera included are briefly discussed. Originally, it contained Pseudocricetodon and Heterocricetodon only, but the number of genera included has grown to at least seven genera during the last decades. Differences in opinion about the content of the subfamily are for a part due to lack of studies in which the Paleogene cricetids from Asia and Europe are directly compared. The material from south-east Serbia described below is assigned to three species: Pseudocricetodon cf. montalbanensis Thaler, 1969, P. heissigi nov. sp. and Heterocricetodon serbicus nov. sp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Pseudocricetodontinae described in this paper are a part of late Eocene-early Oligocene small mammal assemblages found in south-east Serbia. The geological setting and composition of these faunas (consisting mainly of rodents) have been described by de Bruijn et al. (2018) Four rodent groups have been studied and published in print resp. online so far: the Diatomyidae (Marković et al. 2018), the Melissiodontinae (Wessels et al. 2018), the Paracricetodontinae (van de Weerd et al. 2018) and the Pappocricetodontinae (de Bruijn et al. in press), while the publication on the Dipodidae is accepted, but not yet published (Wessels et al. in prep.).

The subfamily Pseudocricetodontinae contains the genera Pseudocricetodon and Heterocricetodon; it has a wide geographical distribution (Eurasia) and occurs from the latest Eocene to the latest Oligocene. In 1987, Engesser included both Pseudocricetodon and Heterocricetodon into the Pseudocricetodontinae, which is supported by the studies of the microstructure of incisor enamel (Kalthoff 2000, 2006).

The aim of this paper to describe the pseudocricetodontines present in the assemblages of localities in Southern Serbia collected in recent years. A short review of the taxonomy of this group of rodents is included.

Methods

The material studied has been collected by wet-screening in the field fossiliferous matrix from Strelac-1, Strelac-2, Raljin, Raljin-B, Valniš and Buštranje on a set of stable sieves. Concentrates have been sorted to the 0.65mm fraction under a microscope. The locality codes of the Natural History Museum in Belgrade and abbreviations used for the localities are 024 for Strelac-1 (STR-1), 025 for Strelac-2 (STR-2), 026 for Strelac-3 (STR-3), 027 for Valniš (VA), 028 for Raljin (RA), 041 for Raljin B (RA-B) and 031 for Buštranje (BUS).

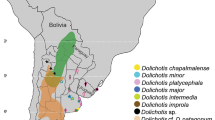

The isolated cheek teeth of Pseudocricetodontinae that will be described and discussed below have been collected by Zoran Marković, Miloš Milivojević, Hans de Bruijn and Wilma Wessels from five Oligocene sites near Strelac in the Babušnica-Koritnica basin and one late Eocene site in the Pčinja basin (south-east Serbia) during the summers of 2010–2015. Figure 1 shows the composition of the rodent faunas. One new site, Raljin-B, was sampled in 2017; it is included in Fig. 1. The site is at the same location as Raljin but stratigraphically about 2 m higher.

All the material will be housed in the Natural History Museum in Belgrade. A representative set of casts of the species recognised is kept in the comparative collection of the Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University. Length and width of the teeth were measured with a Leitz Ortholux microscope with mechanical stage and measuring clocks. The measurements are given in millimetre units. The terminology used for parts of the cheek teeth basically follows Freudenthal et al. (1994). Lower case letters refer to the lower dentition, upper case letters refer to the upper dentition. All figured specimens are shown as from the left side, if the original is from the right side the character on the plates has been underlined.

Taxonomy

Remarks on the subfamily Pseudocricetodontinae Engesser, 1987

Engesser (1987) defined the subfamily Pseudocricetodontinae as including the genera Pseudocricetodon Thaler, 1969 and Heterocricetodon Schaub, 1925 and followed Hugueney (1980) in transferring the species Eucricetodon incertus (Schlosser, 1884) to Pseudocricetodon. Uniting Pseudocricetodon and Heterocricetodon in the same subfamily has been disputed by Kristkoiz (1992) on the basis of difference in skull morphology between specimens from Gaimersheim identified as Pseudocricetodon montalbanensis Thaler, 1969 and Heterocricetodon gaimersheimensis Freudenberg, 1941 (=? Heterocricetodon stehlini Schaub, 1925). Freudenthal et al. (1992) followed Engesser (1987) in including Pseudocricetodon and Heterocricetodon into the Pseudocricetodontinae, a conclusion that has found strong support by the studies of the microstructure of incisor enamel by Kalthoff (2000, 2006). In this context, it is of interest that the type species of Pseudocricetodon (P. montalbanensis Thaler, 1969) and of Heterocricetodon (H. stehlini Schaub, 1925) are very different in size and dental morphology. This suggests that these species probably had very different diets and lifestyles, which may have resulted in adaptations of the skull morphology that are not necessarily of great phylogenetic importance. We consequently consider the Pseudocricetodontinae (sensu Engesser) a firmly established subfamily.

In the meantime, Daams et al. (1989) described the medium-sized pseudocricetodontine Heterocricetodon landroveri from the late Oligocene of Spain. The dentition of this species is in some respects (lophodonty, size) intermediate between the type species of Pseudocricetodon and Heterocricetodon. Later, Freudenthal (1994) described two medium-sized pseudocricetodontine samples from Oligocene sites in Spain, included the older in Heterocricetodon incertus and the supposedly descendant in the new species Heterocricetodon cornelli; the two species are very similar, differing in frequencies of dental features (“character states”) only. The Heterocricetodon incertus holotype is based on a single specimen from a nineteenth century Quercy collection, thus virtually of unknown provenance and age.

The genus Allocricetodon was erected by Freudenthal (1994; type A. cornelli) to house the medium-sized representatives of the subfamily: Pseudocricetodon incertus, P. cornelli and Heterocricetodon landroveri. Alvarez Sierra et al. (1999) considered the diagnostic features of Allocricetodon insufficient and suggested an ancestor-descendant relationship of its type species A. cornelli with Adelomyarion and as a consequence synonymized Allocricetodon with Adelomyarion. In contrast, de Bruijn et al. (2003) and Vianey-Liaud et al. (2014) synonymized Allocricetodon with Pseudocricetodon because the characteristics of Allocricetodon are insufficient to define a separate genus. The morphology of A. cornelli and A. incertus is similar to that of Pseudocricetodon montalbanensis, the genotype of Pseudocricetodon, while the dentition of A. landroveri is more lophodont and seems to anticipate the molar structure seen in Heterocricetodon hausi Engesser, 1987. Thus, the suggestion to synonymize Allocricetodon with Pseudocricetodon does not solve the problem either, because the distinction between Pseudocricetodon and Heterocricetodon is arbitrary.

The status of Oxynocricetodon from the late Eocene of Nei Mongol remains uncertain because the material of the type species O. erenensis Wang, 2007 consists of only eight isolated cheek teeth some of which are incomplete. We have not seen the Chinese material, but the cusps of these teeth seem higher and less incorporated into the lophs than in Heterocricetodon hausi, H. landroveri and H. serbicus. Whether or not this difference justifies separation from the otherwise very similar Heterocricetodon cheek teeth cannot be decided on the basis of the figures in Wang (2007).

We consider Heterocricetodon (Alsocricetodon) telonii Jambor et al. 1969, which is based on a skull found in a core in the Oligocene of Hungary, a nomen nudem because it has neither been described nor figured.

Latocricetodon Joniak et al., 2017 is a new genus erected for Spanocricetodon sinuosus Theocharopoulos, 2000 and tentatively included into the Pseudocricetodontinae by these authors. The reasons presented are exclusively based on the morphology of the cheek teeth, which is in our opinion much closer to the Copemyinae (Democricetodontinae) than to the Pseudocricetodontinae. Since Kalthoff (2000, 2006) has shown that the microstructure of the incisor enamel of these two subfamilies is very different, it would have been better to investigate this essential characteristic in Latocricetodon before its referral to one of these subfamilies. As it is, there seems to be at the moment no sound reason to follow Joniak et al. (2017) on this point.

The growing number of (sub) genera that have been included into the Pseudocricetodontinae by some authors, but that are excluded by others, has resulted in a lively debate (Ünay-Bayraktar 1989; Freudenthal et al. 1992; Kalthoff 2006; Maridet and Ni 2013). Since the material that will be described below does not contribute to this discussion and a revision of the Pseudocricetodontinae is beyond the scope of this study, we refer the reader to the papers listed above and confine ourselves to list the (sub) genera that we consider to belong to the Pseudocricetodontinae. These are the following:

Pseudocricetodon Thaler, 1969 (? = Allocricetodon Freudenthal, 1994 pro parte)

Heterocricetodon Schaub, 1925 (? = Allocricetodon Freudenthal, 1994 pro parte)

Adelomyarion Hugueney, 1969

Lignitella Ünay-Bayraktar, 1989

Kerosinia Ünay-Bayraktar, 1989

Cincamyarion Agusti and Arbiol, 1989

Oxynocricetodon Wang, 2007 (? = Heterocricetodon).

These genera contain a large number of species ranging in size from quite small to large showing minor differences in dental morphology on a gradual scale. Our generic allocation of the Pseudocricetodontinae from Serbia based on subjective characteristics, such as “the degree of lophodonty” and “the shape of the cusps”, is necessarily unsatisfactory.

The Pseudocricetodontinae are relatively common in the Oligocene sites (taken together) in southern Serbia with about 32%. In the Eocene site of Buštranje, the subfamily is represented with 3.5% (Fig. 1).

Remarks on the genus Pseudocricetodon Thaler, 1969

Formally described species

P. montalbanensis Thaler, 1969 (type species of the genus)

P. incertus (Schlosser, 1884)

P. thaleri (Hugueney, 1969)

P. philippi, (Hugueney, 1971)

P. moguntiacus (Bahlo, 1975) (? = P. montalbanensis)

P. orientalis Ünay-Bayraktar, 1989 (? = P. montalbanensis)

P. nawabi Marivaux, Vianey-Liaud and Welcomme, 1999

P. simplex Freudenthal, 1994 (? = P. montalbanensis)

P. adroveri Freudenthal, 1994.

Freudenthal et al. (1994) state that P. orientalis from Turkish Thrace (Űnay-Bayraktar 1989) could be better included in Lignitella; we disagree and leave it in Pseudocricetodon.

The geographical and stratigraphical range of Pseudocricetodon is very large. Representatives have been described from the late Eocene of the lesser Caucasus (de Bruijn et al. 2003), the early Oligocene of Baluchistan (Paali Nala C2, Marivaux et al. 1999; Métais et al. 2009), the late Oligocene of the Baleares (Sineu; Hugueney and Adrover 1982 and Hugueney and Adrover 1989–1990; MP25?) and the early Miocene of France (MN3; Hugueney, 1999). The differences in dental morphology between species are nevertheless very limited. A number of species have primarily been defined on difference in size. Others, such as the geologically younger species Pseudocricetodon philippi, P. thaleri and P. adroveri have a slightly more complex dental pattern and a proportionally somewhat larger anterocone(id) of the M1/m1 than the older ones.

A special case forms Pseudocricetodon simplex Freudenthal, 1994. This species has been differentiated from P. montalbanensis and P. moguntiacus on the basis of differences in the frequency distribution of a large number of character states of the lower and upper molars. The exceptionally rich material of these species from their type localities allowed this approach, but the analyses show conclusively that the overlap in morphology and size of these three species is large. It is in our opinion not useful to formally distinguish species on differences in frequency distributions of character states because this makes smaller samples unidentifiable and serves therefore no practical purpose.

Distinguishing species characteristic clusters in samples of isolated Pseudocricetodon teeth is thus difficult and the Serbian material under study is no exception to this rule. Morphologically, the Serbian material is close to P. montalbanensis. Figure 2 shows the length/width scatter diagrams of the molars of our material from Serbia and those of specimens of P. montalbanensis from the type locality Montalban (Spain) present in the collection of the University of Utrecht. The large size ranges suggest the presence of two species in the Serbian material. The presence of two Pseudocricetodon species in one assemblage has been described from several sites. In Fig. 2, the sizes ranges of the two species in Kocayarma (middle Oligocene of Turkey) have been added as long crosses.

Length/width scatter diagrams of the Pseudocricetodon cheek teeth from the Paleogene of south-east Serbia and those of P. montalbanensis (red points) from its type locality. The assemblages of Strelac-3 and Raljin-B show a wide range in the size distribution of the M2, m1 and m2 suggesting presence of two species; the ellipses indicate the probable two species. Presence of two species cannot be demonstrated in the assemblages of Buštranje, Raljin and Strelac-1. The size ranges of the two Pseudocricetodon species from Kocayarma the large P. orientalis and the small P. philippi, are indicated for comparison

The size of the molars from the sites of Buštranje and Valniš (blue triangles and squares in Fig. 2) clusters in a relatively tight group that is smaller and overlapping the size of the smaller specimens of Pseudocricetodon montalbanensis from the type locality Montalban (red points). In contrast, the population from Strelac-3 (black stars) shows a large range in size in particular clear in the M2, m1 and m2 suggesting presence of two species with partially overlapping size ranges. Some of the M1/m1, M2/m2 from Strelac-3 are within the range or larger than those of P. montalbanensis, while others are smaller (indicated with ellipses in Fig. 2). Comparison of our measurements with the data presented in Freudenthal and Cuenca Bescos (1984) confirms that the coefficient of variation of the second molars is too large for one homogeneous cricetid population. Similarly, the small and the large species are present as well in Raljin-B. The size distribution of the molars from Strelac-1 and Raljin does not suggest presence of two species, but considering possible presence of two species differing in size, the two M1 from Raljin could belong to the small species and the single m2 of Raljin to the large species (Fig. 2). A distinction between the larger and smaller species cannot be made in the M3 and m3. Since the M3/m3 from all the assemblages are more or less within the size range of P. montalbanensis, the smaller species probably had proportionally larger M3/m3.

The larger species present in Strelac-3, Raljin-B and Raljin is allocated to P. cf. montalbanensis. The smaller species is new and will be defined on the basis of the specimens from Strelac-3. However, the teeth of the smaller and the larger species overlap in morphology and in size. The distinction between the smaller (new) species and the larger species (cf. montalbanensis) in our material is often not clear. It can therefore not be excluded that some specimens are misidentified: larger specimens of the small (new) species may represent the larger species (cf. montalbanensis) and the other way round, small specimens of the larger species may represent the small (new) species.

Remarks on genus Heterocricetodon Schaub, 1925

We follow Freudenthal (1994) in regarding the large H. schlosseri Schaub, 1925, H. gaimersheimensis Freudenberg, 1941 and H. helbingi Stehlin and Schaub, 1951 junior synonyms of H. stehlini for the time being. The only good collection of a large Heterocricetodon species available is H. gaimersheimensis from Gaimersheim. This material that was studied in detail by Kristkoitz (1992) shows considerable metrical and morphological variation, so it is quite possible that the scanty type materials of H. schlosseri, H. stehlini and H. helbingi represent the same large species that is present in Gaimersheim. Since there were two fissure fillings in the former Gaimersheim quarry, it has been argued that the large variation observed in some species from this locality is due to temporal heterogeneity of the material. This view is expressed on the correlation chart published in the proceedings of the International Symposium on Mammalian Biostratigraphy and Palaeoecology of the European Paleogene where Gaimersheim 2 was included in MP28 and Gaimersheim 1 in MP27 (Schmidt-Kittler 1987). However, the study of the rodent assemblage from Gaimersheim by Kristkoitz (1992) shows homogeneous samples and does therefore not support the idea that the fauna is mixed and it was included in MP27. Therefore, Vianey-Liaud et al. (2014) include their material from Saint-Privat-des-Vieux (MP26) in H. gaimersheimensis because the holotype and single specimen of H. stehlini is of unknown origin and age (“Bach”, old Quercy collection).

Species that are (tentatively) included into the genus are as follows:

H. gaimersheimensis Freudenberg, 1941

H. hausi Engesser, 1987 described from Bumbach (MP25),

H. landroveri Daams, Freudenthal, Lacomba and Alvarez, 1989 from the Oligocene Pareja site in Spain (MP25),

Oxinocricetodon erenensis Wang, 2007 (from the late Eocene of Nei Mongol),

H. serbicus n. sp.

The genus is absent in the latest Eocene and the Oligocene sites of Thrace and Anatolia (Ũnay et al. 2003). A single worn m2 in Kocayarma (Turkish Thrace) was erroneously identified as Heterocricetodon (Ünay-Bayraktar 1989, plate 7 Fig. 5) instead of included in Edirnella (Marković et al. 2018).

Systematic palaeontology

Muridae Illiger, 1811

Pseudocricetodontinae Engesser, 1987

Pseudocricetodon Thaler, 1969

Type species:P. montalbanensis Thaler, 1969 (Figs. 3a–f and 4a–f)

Pseudocricetodon montalbanensis from Montalban B: a M1 MON-513, b M2 MON-556, c M3 MON-602, d M1 MON-536, e M2 MON-587, f M3 MON-593. P. cf. montalbanensis Strelac-1 and Strelac-3 (024 and 026): g M1 STR3-176, h M2 STR3-186, i M3 STR3-191, j M1 STR-131, l M3 STR3-195, P. cf. heissigi Buštranje (031) and Valniš (027): k M2 VA-416; m M1 BUS-1322, n M2 BUS-1334, o M3 VA-423, r M3 VA-422. P. heissigi nov. sp. Strelac-3 (026): p M1 STR3-173, q M2 STR3-187

Pseudocricetodon montalbanenis Montalban: a m1 MON-460, b m2 MON-487, C m3 MON-523, d m1 MON-431, e m2 MON-466, f m3 MON-460. P. cf. montalbanenis Strelac-3 (026): g m1 STR3–202, h m2 STR3-213, i m3 STR-225. P. cf. heissigi Buštranje (031): j m1 BUS-1373, k m2 Bus-1381, l m3 BUS-1411. Valniš (027): p m1 VA-431, q m2 VA-442, r m3 VA-451, u m3 VA-452. P. heissigi nov. sp. Strelac-3 (026): s m1 STR3-203, t m2 STR3-215.

Type locality: Montalban, Spain (early Oligocene, MP23).

Material and measurements collection Utrecht University: Table 1, Fig. 2.

Pseudocricetodon cf. montalbanensis Thaler, 1969

Localities: Strelac-1, Strelac-3, Raljin-B

Material and measurements: Tables 1 and 3 and Fig. 2.

Description

M1: There are two more or less complete M1 from Strelac-1 (Fig. 3j) and damaged specimens from Strelac-3 (Fig. 3g) and Raljin B. The short anterior arm of the protocone ends free in the anterosinus. The weak protolophule inserts on the anterior or the posterior arm of the protocone. The sinus is directed forwards and the weak mesoloph is short. Some M1 have a small mesostyle. The transverse metalophule connects the metacone to the hypocone. The long posteroloph reaches the base of the metacone.

M2: The only M2 available from Strelac-1 is relatively long (Fig. 2) and has an aberrant dental pattern. The specimens from Strelac-3 are very similar to the ones from Montalban (Fig. 3b, e, h). The long labial branch of the anteroloph is almost straight and reaches to the base of the paracone. The protolophule and metalophule are directed slightly forwards and insert on the anterior arm of the protocone and hypocone. The M2 have two short mesolophs, in a damaged specimen from Strelac-3 these are long almost reaching the labial border. The long posteroloph reaches the base of the metacone.

M3: The M3 of the larger species P. cf. montalbanensis and the small new species cannot be distinguished, although the large specimens may belong P. cf. montalbanensis and the small specimens to the small species. Clear morphological differences are not present.

The labial branch of the anteroloph is long. The protolophule inserts on the anterior arm of the protocone. One of the three specimens from Strelac-3 shows a neo-entoloph, but the sinus is preserved in two M3. The mesoloph is short or of medium length and the metalophule is complete. The metacone is incorporated into the posteroloph.

m1: Two m1 from Strelac-3 and one from Raljin-B are allocated to P. cf. montalbanensis (Fig. 2). The anteroconid of the m1 is situated on the central longitudinal axis of the occlusal surface. Its labial and lingual branch are about equally strong, which leads to a boat-shaped tooth. The anterolophulid (= anterior arm of the protoconid) is complete in two of the three specimens. The metalophulid 1 is weak or absent while the metalophulid 2 is formed by the posterior arm of the protoconid. The low ectolophid bears two weak mesolophids. The transverse hypolophulid inserts on the hypoconid and the long posterolophid merges with the entoconid.

m2: Four m2 from Strelac-3 and three from Raljin-B are allocated to P. cf. montalbanensis (Fig. 2). Most m2 have a rather pronounced anteroconid which divides the anterolophid into a long lingual branch and a much shorter labial branch. The more or less transverse parallel metalophulid and hypolophulid are long and insert on the anterior sides of the protoconid and hypoconid. The long posterior arm of the protoconid is variable in length, it ends free or is more or less connected to the metaconid. The long posterolophid merges low with the entoconid. All m2 show a short mesolophid.

m3: The m3 of the larger species P. cf. montalbanensis and the small new species cannot be distinguished, although the large specimens may belong to P. cf. montalbanensis and the small specimens to the small species. Clear morphological differences are not present. The dental pattern of the m3 is not much reduced relative to that of the m2. The somewhat forwards curving metalophulid and hypolophid insert on the anterior arm of the protoconid and hypoconid. The long posterior arm of the protoconid ends free.

Discussion

The teeth from Strelac-1 and Strelac-3 identified as P. cf. montalbanensis fit morphologically within the individual variation of the assemblage from the type locality of that species studied by Freudenthal et al. (1994). However, metrically, the specimens from Serbia are as large as or larger than the largest specimens from the type locality Montalban.

This small, presumably ground-dwelling, murid that was originally described from the early Oligocene (MP23) of Montalban in Spain has later been recognised in, among others, the assemblages from the late Eocene of Süngülü in eastern Turkey (de Bruijn et al. 2003) and the late Oligocene (MP27) locality Gaimersheim in Bavaria (Kristkoitz 1992). Apparently, the stratigraphical and geographical range of P. montalbanensis is large.

Pseudocricetodon heissigi nov. sp.

Type locality: Strelac-3.

Holotype: M1 sin. Strelac-3 (026–173) Fig. 3p

Derivatio nominis: In honour of Dr. Kurt Heissig (Munich), who recognised the special character of the Eocene-Oligocene Balkan biogeographical province as early as 1979.

Material and measurements: P. heissigi from the typelocality Strelac-3: See Table 2

Diagnosis

P. heissigi is a very small Pseudocricetodon with a low, retracted and transversely oriented anterocone in the M1.

Differential diagnosis

The sizes of the cheek teeth of P. heissigi are on average smaller than those of all other species of Pseudocricetodon except P. philippi from St. Martin-de-Castillon. The Serbian species differs from P. philippi Hugueney, 1971 (illustrated by Freudenthal et al. 1994) by its retracted, transversely oriented anterocone of the M1 and by its lower-crowned cheek teeth.

Description

M1: Three complete and three damaged specimens from Strelac-3 are allocated to P. heissigi. The middle specimen of Fig. 2 is the holotype. The ridge-like anterocone of the M1 has a rather labial position and is situated on a straight line with the paracone and metacone. The anterior arm of the protocone ends free in the anterosinus. The protolophule inserts in two specimens on the anterior arm of the protocone in four on its posterior arm. The shallow sinus is directed slightly forwards. The metaloph inserts in front of the hypocone. The long posteroloph is straight. The single mesoloph is short and there is a small mesostyl.

M2: The rather worn and broken specimen from Strelac-3 has a long labial branch of the anteroloph and a rudimentary lingual branch. The parallel protolophule and metalophule insert on the anterior side of the protocone and hypocone respectively. The posteroloph is long. There are two short mesolophs.

M3: All M3 in the studied Serbian faunas are allocated to P. cf. montalbanensis because morphology and size do not allow a separation into two species. One of the three specimens from Raljin-B (see Fig. 2) is distinctly smaller and may represent P. heissigi.

m1: A single m1 from Strelac-3 has been allocated to P. heissigi. The single anteroconid is situated at the central longitudinal axis. It has about equally long lingual and labial branches, which reach the bases of the metaconid respectively the protoconid. The anterolophulid is in line with the ectolophid. The metalophulid-2 inserts on the posterior side of the protoconid, a weak metalophulid-1 is present. The hypolophulid is about parallel with metalophulid-2 and inserts on the hypoconid. A short posterior arm of the protoconid and a weak short mesolophid are in the mesosinusid. The long posterolophid reaches the entoconid. A narrow entolophid connects the entoconid and the metaconid along the border of the occlusal surface.

m2: Four m2 from Strelac-3 have been allocated to P. heissigi. The lingual branch of the anterolophid is long, but the labial branch is vestigial. The metalophulid and hypolophulid are parallel and transverse. These lophids insert on the anterior side of the protoconid and hypoconid. The posterior arm of the protoconid and the mesolophid are of medium length and end free in the mesosinusid. An ectomesolophid is present. The long posterolophid reaches the base of the entoconid.

Pseudocricetodon cf. heissigi

(Figs. 3 k, m–o, r and 4j–r, u)

Material and measurements of P. cf. heissigi from Buštranje, Valniš, Raljin and Raljin-B: see Tables 2 and 3, Fig. 2.

Description

M1: From Buštranje are three complete specimens and three without anterocone. The anterocone seems slightly more lingual than in the holotype of P. heissigi. The protolophule inserts in one specimen on the anterior arm of the protocone (Fig. 3m) in five on its posterior arm. In the latter specimens, the anterior arm is short and ends free in the anterosinus. The metaloph inserts in front of the hypocone all specimens. The metaloph is short and four out of six specimens have a mesostyle. In all four incomplete Valniš specimens, the protolophule connects to the posterior arm of the protocone. The metaloph is short and a mesostyle is absent or barely visible. One of the two Raljin specimens is rather worn, it has a double protolophule.

M2: All Valniš specimens have the protolophule connected to the anterior arm of the protocone, the posterior arm is short. The mesoloph is short in all except one in which the mesoloph is reaching the border. The metaloph connects to the anterior side of the hypocone. The ten Buštranje specimens are all very similar. One specimen (Fig. 3n) shows a neo-entoloph, closing the sinus.

M3: The Pseudocricetodon molars in assemblages from Buštranje and Valniš do not suggest presence of two species (Fig. 2) and all molars from these sites including the M3 may be allocated to P. cf. heissigi. Morphologically and metrically, the M3 from Valniš is similar to those of the other assemblages that may contain two species. The M3 has not been found in the assemblage from Buštranje. Two specimens from Valniš are shown in Fig. 3o, r.

m1: The anteroconid in unworn Buštranje specimens can be a rather low ridge or it is well-developed as in Fig. 4j. The anterolophulid is low and variable, in line with the ectolophulid. All specimens have a metalophulid 2, in 4 out of 8 specimens an irregular low metalophulid 1 tends to develop. The mesolophid is low or indistinct to absent. The six Valniš specimens have a low ridge-like anteroconid. A metalophulid 2 is present, the metalophulid 1 is absent. Mesolophids are very low to absent, a vestige of an ectomesolophid is present in some specimens (Fig. 4p).

m2: The metalophulid connects to the anterior arm of the protoconid in the Valniš specimens (Fig. 4q), the posterior arm ends free, some specimens have a short mesolophid too. A short and low ectomesolophid tends to be present in about three of the seven Valniš specimens. The five Buštranje specimens are all similar to Fig. 4k with an anterior connection of the metalophulid and hypolophulid to the protoconid and hypoconid respectively. In the mesosinusid are the low and short posterior arm of the protoconid and mesolophid. Two of the five specimens have an ectomesolophid.

m3: The Pseudocricetodon molars in assemblages from Buštranje and Valniš do not suggest presence of two species (Fig. 2) and hence the m3 may be allocated to P. cf. heissigi too. Morphologically and metrically, the m3 from Valniš and Buštranje are similar to those of the other assemblages that may contain two species. Specimens from Valniš and Buštranje are shown in Fig. 4r, l, u. In one specimen from Buštranje, the long posterior arm of the protoconid developed into a metalophulid 2.

Discussion

Identification of the Pseudocricetodon material described above posed problems because the samples per locality are small, while the total size range of the first and second molars is great and suggests, by comparison with the large sample from Montalban, that the material of several of the Serbian localities is not homogeneous. Yet separation of species on the basis of size is possible in the samples from Strelac-3 only, while the morphology of the cheek teeth of the two species is very similar and does not allow their separation. Since the size ranges of the teeth from the localities Buštranje and Valniš are of the order of magnitude expected in one species and these samples tend to be smaller than P. montalbanensis, we have allocated these samples tentatively to the smaller species P. cf. heissigi. In addition, we have allocated the few small specimens that we have from Raljin and Raljin-B to P. cf. heissigi.

Heterocricetodon Schaub, 1925

Type species:H. stehlini Schaub, 1925

Heterocricetodon serbicus nov. sp.

Derivatio nominis: After the country of provenance

Typelocality: Valniš (code 027)

Holotype: M1 sin. Valniš 027 VA-501

Material and measurements: see Table 5

Other localities with Heterocricetodon serbicus n. sp.: Strelac-1, Strelac-2. Strelac-3, Raljin and Raljin-B. See Tables 4, 5, and 6

Diagnosis

H. serbicus is a small species of Heterocricetodon. The cusps of unworn cheek teeth are low, blunt and incorporated into the rather thick lophs. The mesolophs of the M1 and M2 rarely reach the well-developed mesostyle. The occlusal surface of the M2 is longer than wide and the average length of the m1, m2 and m3 is about the same. The morphological and metrical variation among cheek teeth from the various loci is large. Part of the lower molars shows a low and rather large ectostylid. The occlusal surface becomes almost flat in worn specimens.

Differential diagnosis

Heterocricetodon serbicus is larger than Pseudocricetodon montalbanensis, P. simplex, P. adroveri, P. philippi, P. thaleri, P. moguntiacus and P. orientalis. Some of its cheek teeth overlap in size with those of Heterocricetodon landroveri, Pseudocricetodon nawabi, Pseudocricetodon incertus and “Allocricetodon” cornelli, ergo, the species assembled in the genus Allocricetodon by Freudenthal (1994) and Freudenthal et al. (1994). The Serbian species differs from all of these by having an M2 that is longer than wide and by having lower cheek teeth that are on average about equally long, a metrical characteristic that Heterocricetodon serbicus shares with H. stehlini from Gaimersheim.

Description

M1: The rather high, but blunt, unicuspid anterocone of the M1 has a labial position. The lingual branch of the anterocone is connected to the protocone. In some specimens, this ridge incorporates a protostyl. The weak labial branch of the anterocone may be connected to the paracone. The anterior arm of the protocone is long. It reaches the anterocone in one specimen, ends free in the protosinus in four and is part of the protolophule in five M1. The more or less transverse protolophule is weak and sometimes interrupted just before reaching the anterior arm of the protocone. The sinus is directed strongly forwards. The entoloph is often weak behind the protocone and may be interrupted. A weak protolophule 2 is present in two out of ten M1. The mesoloph is short and does not reach the mesostyle. The transverse metalophule inserts either on the hypocone or on the anterior arm of the hypocone. The long straight posteroloph delimits the posterosinus.

M2: The long, straight labial branch of the anteroloph ends labially in a cusp that is separated from the paracone by a notch in most specimens. The lingual branch of the anteroloph is developed as a weak, low cingulum. The transverse or slightly forwards directed protolophule inserts on the anterior arm of the protocone. Three out of 17 M2 from Valniš and one out of four M2 from Strelac-1 show a short ridge in the protosinus. The posterior arm of the protocone is short in most M2 and forms an incipient incomplete protolophule 2, but in others this structure is missing. The mesoloph is short in most specimens and does not reach the, often well developed, mesostyl. The transverse metalophule inserts on the anterior arm of the hypocone. The forwards directed sinus is open at its apex in one out of 17 M2 from Valniš. The long posteroloph reaches the base of the metacone in some M2, but is separated from that cusp by a notch in others.

M3: The metrical and morphological variation is exceptionally large among the M3. The labial branch of the anteroloph is long, but the lingual branch is weak or absent. The protolophule is directed slightly forwards in most M3 and inserts in front of the protocone. The sinus is shallow and directed forwards. The mesoloph is absent in some specimens, but in the majority it is of medium length. The metalophule is more or less transverse in most M3, but is incomplete or fused with the posteroloph in some others. The posteroloph reaches the base of the metacone in most specimens.

m1: The undivided anteroconid of the m1 is rather small and situated close to the protoconid and metaconid. Its lingual branch is short and does not reach the metaconid in most specimens. The labial branch is usually slightly better developed, but does not connect to the protoconid. A metalophulid 1 is absent and the short, weak metalophulid 2 is formed by the posterior arm of the protoconid. The anteroconid is connected to the protoconid by a short anterolophulid. The ectolophid is almost straight and bears a mesoconid in four out of six m1 from Valniš. A distinct mesostylid is present in all m1 except one from Valniš. The ectomesolophid is weak or absent. The roughly transverse hypolophulid inserts on the anterior arm of the hypoconid. The posterolophid reaches the base of the entoconid.

m2: The lingual and the labial branch of the anterolophid are well developed, and so is the anterolophulid that connects the protoconid to the anterolophid. The metalophulid is transverse and inserts on the anterior arm of the protoconid in 12 out of 14 m2 from Valniš. In three m2, this ridge is weak and interrupted. The mesolophulid is short or absent in most specimens, but four out of 14 m2 from Valniš have two mesolophulids. A few m2 have a weak ectomesolophid and some others have a low ectostylid. The hypolophulid is either transverse or curves slightly forwards. The long posterolophid is connected to the entoconid.

m3: The variation in size and morphology among the m3 is large. The anterolophid of most specimens shows a long lingual branch and a short labial branch, but in some m3, the anterior arm of the protoconid continues along the anterior side of the occlusal surface incorporating the labial branch of the anterolophid. The metalophulid is generally complete and transverse, but in some m3, this ridge is incomplete or absent because it is fused with the lingual branch of the anterolophid. The posterior arm of the protoconid usually ends free in the mesosinusid, but three out of the 16 m3 from Valniš it forms a metalophulid 2. In one m3, this structure is absent and in one specimen it is long and reaches the lingual outline of the occlusal surface. A true mesolophid is present in three out of 16 m3 from Valniš only. The hypolophulid is either transverse or curves somewhat forwards labially. The sinusid is shallow and bears a distinct ectostylid in one specimen only. The long posterolophid reaches the entoconid in some, but is separated from that cusp by a notch in others. Fifteen out of 16 m3 from Valniš do not show a trace of a posterior arm of the hypoconid, but in one specimen this structure is strong.

Remark

The largest assemblage of H. serbicus is from Valniš. Size and morphology of the molars of the smaller assemblages fall completely within the size ranges of the molars from Valniš.

Discussion and conclusions

The Pseudocricetodontinae are a subfamily with a Eurasian geographical range and a combined stratigraphical range that covers all of the Oligocene and the latest Eocene. The subfamily is relatively common in the Oligocene sites of southern Serbia with 33% and relatively rare in the Eocene site of Buštranje with 3.5%. Two species of Pseudocricetodon are present, P. heissigi nov. sp. and P. cf. montalbanensis, and one new species of Heterocricetodon. Pseudocricetodon is common in the “middle” Oligocene rodent assemblages of Thrace (Turkey and Kyprinos in Greece) with 16 to 40%. The largest of these associations are Kavakdere and Kocayarma (Ünay-Bayraktar 1989), where similar to Strelac-3 and Raljin-B two species are present. The larger P. orientalis and a smaller species have been identified as P. philippi, but it seems to be closer to P. heissigi. A Pseudocricetodon species close to P. montalbanensis has been described by de Bruijn et al. (2003) from the latest Eocene site of Süngülü in Anatolia where it is present with about 13% in the rodent fauna.

The well-described succession from Spain (Freudenthal 1994; Freudenthal et al. 1994; Freudenthal 1997) shows that pseudocricetodontines arrived relatively late in south-western Europe, the oldest occurrence is Pseudocricetodon sp. just below the level with P. montalbanensis (MP23) in the section near Montalban Spain (Freudenthal et al. 1992). This group of supposedly closely related Pseudocricetodon species (P. montalbanensis, P. simplex, P. adroveri) continues until in MP28.

Heterocricetodon from the early Oligocene sites of Strelac, Valniš and Raljin is probably the oldest record of the genus. In Western Europe, the genus is present in the Swiss Molasse basin with Heterocricetodon hausi (Bumbach-1, MP25) and in Spain (Lorenca basin and the Montalban area) with H. landroveri (MP 26). Heterocricetodon (H. landroveri, H. hausi) arrived in Spain in MP25 and continues until in zone MP28. Comparison of the early Oligocene succession in Spain with that of the Balkan confirms the absence of, or limited fauna exchange, during the late Eocene and early Oligocene between these regions.

References

Agusti, J., & Arbiol, S. (1989). Nouvelles espèces de rongeurs (Mammalia) dans l’ Oligocène supérieur du bassin de l’Ebre (N.E. de l’Espagne). Geobios, 22(3), 265–275.

Alvarez Sierra, M. A., Daams, R., & Pelaez-Campomanes, P. (1999). The Late Oligocene rodent faunas of Canales (MP 28) and Parrales (MP 29) from the Loranca basin, province of Quenca, Spain. Revista Española de Paleontología, 14, 93–116.

Bahlo, E. (1975). Die Nagetierfauna von Heimersheim bei Alzey (Rheinhessen, Westdeutschland) aus dem Grenzbereich Mittel/Oberoligozän und ihre stratigraphische Stellung. Abhandlungen des Hessischen Landesamtes für Bodenforschung, 71, 1–182.

Bruijn, H. de, Ünay, E., Saraç, G., & Yilmaz, A. (2003). A rodent assemblage from the Eo/Oligocene boundary interval near Süngülü, Lesser Caucasus, Turkey. In N. López-Martinez, P. Peláez-Campomanes, & M. Hernández Fernández (Eds.), En torno a fósiles de mamίferos: datacion, evolucion y paleoambiente. Colloquios de Paleontologia, Volumen Extraordinario no 1. En honor al dr. Remmert Daams. Universidad Computense de Madrid, pp 47–76.

Bruijn, H. de, Marković, Z., Wessels, W., Milivojević, M., & Weerd, A. A. van de (2018). Rodent faunas from the Paleogene of south-east Serbia. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 98(3), 441–458.

Bruijn, H. de, Marković, Z., Wessels, W., & Weerd, A. A. van de (in press). Pappocricetodontinae (Rodentia, Muroidea) from the Paleogene of south-east Serbia. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-018-0343-2.

Daams, R., Freudenthal, M., Lacomba, J. I., & Alvarez, M. (1989). Upper Oligocene micromammals from Pareja, Loranca Basin, prov. of Guadalajara, Spain. Scripta Geologica, 89, 27–56.

Engesser, B. (1987). New Eomyidae, Dipodidae and Cricetidae (Rodentia, Mammalia) of the Lower Freshwater Molasse of Switzerland and Savoy. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 80(3), 945–993.

Freudenberg, H. (1941). Die Oberoligozänen Nager von Gaimersheim bei Ingolstadt und ihre Verwandten. Palaeontographica, Abteilung A, 92, 99–164.

Freudenthal, M. (1994). Cricetidae (Rodentia, Mammalia) from the Upper Oligocene of Mirambueno and Vivel del Rio (prov. Teruel, Spain). Scripta Geologica, 104, 1–55.

Freudenthal, M. (1997) Paleogene Rodent Faunas from the Province of Teruel (Spain). In J. P. Aguilar, S. Legendre, J. Michaux (Eds.), Biochronologie mammalienne du Cénozoique en Europe et domaines reliés - Mémoires et Travaux de l’Institute, École Pratique des Hautes études, vol 21. pp 397–415.

Freudenthal, M., & Cuenca Bescos, G. (1984). Size variation of fossil rodent populations. Scripta Geologica, 76, 1–27.

Freudenthal, M., Lacomba, J. I. & Sacristán, M. A. (1992). Classification of European Oligocene cricetids. Revista Espagñola de paleontologίa, Extra, pp 49–57.

Freudenthal, M., Hugueney, M., & Moissenet, E. (1994). The genus Pseudocricetodon (Cricetidae, Mammalia) in the Upper Oligocene of the province of Teruel (Spain). Scripta Geologica, 104, 57–114.

Hugueney, M. (1969). Les rongeurs de l’Oligocène supèrieur de Coderet-Bransat (Allier). Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie, Faculté des Sciences de Lyon, 34, 1–277.

Hugueney, M. (1971). Pseudocricetodon philippi, nouvelle espèce de cricétidae (Rodentia, Mammalia) de l’Oligocène moyen de Saint-Martin-de-Castillon (Vaucluse). Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, D, 272(20), 2533–2535.

Hugueney, M. (1980). La faune de mammifères de l’Oligocène moyen de Saint-Menoux (Allier). Première partie: Rongeurs (Mammalia, Rodentia). Revue scientifique du Bourbonnais, pp 57–71.

Hugueney, M. (1999). Genera Eucricetodon and Pseudocricetodon. In G. E. Rössner & K. Heissig (Eds.), The Miocene Land Mammals of Europe (pp. 347–358). München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil.

Hugueney, M., & Adrover, R. (1982). Le peuplement des Baléares (Espagne) au Paléogène. Geobios, Mémoire Spécial, 6, 439–449.

Hugueney, M. & Adrover, R. (1989–90). Rongeurs (Rodentia,Mammalia) de l’Oligocène de Sineu (Baléares, Espagne). Paleontologia i Evolució, 23, 157–169.

Illiger, C. (1811). Prodromus systematis mammalium et avium additis terminis zoographicis utriusque classis, eorumque versione germanica (pp. 1–301). Berolini: Sumptibus C. Salfeld.

Jámbor, Á., Korpás, L., Kretzoi, M., Pálfalvy, I., & Rákosi, L. (1969). A dunántúli oligocén rétegtani problémái (Stratigraphische Probleme des transdanubischen Oligozäns). Annual Report Geological Institute Hungary, 1969, 141–154 (in Hungarian with short German abstract).

Joniak, P., Pelaez-Campomanes, P., van den Hoek Ostende, L. W., & Rojay, B. (2017). Early Miocene rodents of Gokler (Kazan Basin, Central Turkey). Historical Biology. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2017.1414211.

Kalthoff, D. C. (2000). Die Schmelzmicrostructur in den Incisiven der hamsterartigen Nagetiere und anderer Myomorpha (Rodentia, Mammalia). Palaeontographica, Abteilung A, 269, 1–193.

Kalthoff, D. C. (2006). Incisor enamel microstructure and its implications to higher-level systematics of Eurasian Oligocene and Early Miocene hamsters (Rodentia). Palaeontographica, Abteilung A, 277(1–6), 67–81.

Kristkoitz, A. (1992). Zahnmorphologische und schädelanatomische Untersuchungen an Nagetieren aus dem Oberoligozän von Gaimersheim (Süddeutschland). Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse, Abhandlungen, Neue Folge, 167, 1–137.

Maridet, O., & Ni, X. (2013). A new cricetid rodent from the Early Oligocene of Yunnan, China, and its evolutionary implications for early Eurasian cricetids. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 33(1), 185–194.

Marivaux, L., Vianey-Liaud, M., & Welcomme, J. L. (1999). Première découverte de Cricetidae (Rodentia, Mammalia) Oligocènes dans le synclinal sud de Gandoe (Bugti Hills, Baluchistan, Pakistan). Comptes Rendus de l’Academie des sciences de Paris, 329(11), 839–844.

Marković, Z., Wessels, W., Weerd, A. A. van de, & Bruijn, H. de (2018). On a new diatomyid (Rodentia, Mammalia) from the Paleogene of south-east Serbia, the first record of the family in Europe. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 98(3), 459–469.

Métais, G., Antoine, P.-O., Hassan Baqri, S. R., Crochet, J.-Y., De Franceschi, D., Marivaux, L., & Welcomme, J.-L. (2009). Lithofacies, depositional environments, regional biostratigraphy and age of the Chitarwata Formation in the Bugti Hills, Balochistan, Pakistan. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 34, 154–167.

Schaub, S. (1925). Die hamsterartige Nagetiere des Tertiärs und ihre lebenden Verwandten. Abhandlungen Schweizerische Paläontologische Gesellschaft, 45, 1–114.

Schlosser, M. (1884). Die Nager des Europäischen Tertiärs. Palaeontographica, 31, 1–143.

Schmidt-Kittler, N. (1987). European reference levels and Correlation tables. Münchner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, 10, 13–20.

Stehlin, H. G., & Schaub, S. (1951). Die Trigonodontie der simplicidentaten Nager (pp. 1–373). Basel: Verlag Birkhäuser AG.

Thaler, L. (1969). Rongeurs nouveaux de l’Oligocène moyen d’Espagne. Palaeovertebrata, 2(5), 191–207.

Theocharopoulos, C. D. (2000). Late Oligocene-Middle Miocene Democricetodon, Spanocricetodon and Karydomys n. gen. from the eastern Mediterranean area. Gaia, 8, University of Athens, pp 1–92.

Ünay-Bayraktar, E. (1989). Rodents from the Middle Oligocene of Turkish Thrace. Utrecht Micropaleontological Bulletins, special publication, 5, 5–95.

Ũnay-Bayraktar, E., Bruijn, H. de, & Saraç G. (2003). The Oligocene rodent record of Anatolia: a review. In W. F. Reumer, & W. Wessels (Eds.), Distribution and migration of Tertiary mammals in Eurasia. Deinsea, Annual of the Natural History Museum, Rotterdam, pp 531–537.

Vianey-Liaud, M., Comte, B., Marandat, B., Peigne, S., Rage, J.-C., & Sudre, J. (2014). A new early Late Oligocene (MP 26) continental vertebrate fauna from Saint-Privat-des-Vieux (Alès Basin, Gard, Southern France). Geodiversitas, Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle Paris, 36(4), 565–622.

Wang, B. Y. (2007). Late Eocene cricetids (Rodentia, Mammalia) from Nei Mongol, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 7, 195–212.

Weerd, A. A. van de, Bruijn, H. de, Marković, Z., & Wessels, W. (2018). Paracricetodontinae (Mammalia, Rodentia) from the late Eocene and early Oligocene of S. E. Serbia. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 98(3), 489–508.

Wessels, W., Weerd, A. A. van de, Bruijn, H. de, & Marković, Z. (2018). New Melissiodontinae (Mammalia, Rodentia) from the Paleogene of south-east Serbia. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 98(3), 471–487.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the facilities offered during our fieldwork by Jovan Stojanović and the staff of motel Nina (Babušnica) and by Mile Ilić at the premises of the old mill of Ljuberadja. We are very grateful to Miloš Milivojević (NHMB) for his dedicated work in the field and laboratory. The SEM pictures of the cheek teeth were made by Tilly Bouten (Utrecht University). The plates were prepared by Margot Stoete (Utrecht University). Marijn Lockefeer is thanked for his expert Latin advice. The field work has been supported financially by the Museum of Natural History in Beograd, by the Hans de Bruijn Foundation and by the Department of Earth Sciences (Utrecht University). This paper benefited from reviews by M. Hugueney and an anonymous reviewer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is registered in Zoobank under urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:FB7A98CC-D7CF-4899-8A00-B5C4105F1086

This is the sixth paper in the series: “The Paleogene rodent faunas from south-east Serbia”.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marković, Z., Wessels, W., van de Weerd, A.A. et al. Pseudocricetodontinae (Mammalia, Rodentia) from the Paleogene of south-east Serbia. Palaeobio Palaeoenv 100, 251–267 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-019-00373-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-019-00373-8