Abstract

Digital ecosystems are a highly relevant phenomenon in contemporary practice, offering unprecedented value creation opportunities for both companies and consumers. However, the success of these ecosystems hinges on their ability to establish the appropriate incentive systems that attract and engage diverse actors. Following the notion that setting “the right” incentives is essential for forming and growing digital ecosystems, this article presents an integrated framework that supports scholars and practitioners in identifying and orchestrating incentives into powerful incentive systems that encourage active participation and engagement. This framework emphasizes the importance of understanding how individuals and groups are motivated to engage in the ecosystem to incentivize them effectively. To demonstrate its applicability and value, we show its application in the context of an emergent digital ecosystem within the Smart Living domain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In today’s highly competitive business environment, digital ecosystems (DEs) are a pathway to success and growth (Subramaniam et al., 2019). As digital counterparts of natural ecosystems, digital ecosystems are self-organizing, robust, and scalable environments where various species (i.e., hardware, software, platforms, consumers, and companies) interact with each other to solve complex problems (Hein et al., 2020; Teece, 2018). DEs can also be described as dynamic multi-player environments where value co-creation relies heavily on exchanging data and services between different actors (Hein et al., 2020; Wang, 2021). Such actors might include technology and platform providers, operators of digital artifacts, vendors of technical devices, and consumers (Bonina et al., 2021; B. Tan et al., 2015; F. Tan et al., 2016).

In this paper, we introduce a framework designed to facilitate the successful formation of DEs. After all, DEs do not just emerge. Instead, they are the results of one or various key actors’ efforts (usually one or more companies) that team up to create more value than they could on their own (Jacobides et al., 2018). As practice shows, efforts and success to develop digital ecosystems vary significantly. Within this literature, scholars document that one crucial success factor for DEs lies in finding the suitable set of incentives—i.e., incentives and incentives systems—to ensure that ecosystem participation and user enrollment are self-perpetuating (Jacobides, 2019; Lettner et al., 2022; Valdez-De-Leon, 2019).

Incentives are the motivation or reason for someone to take a particular action. Incentive systems, however, are a structured and coordinated set of incentives that work together to drive a specific behavior or set of behaviors over time (Deci et al., 1999). In the context of DEs, incentive systems encompass various stimuli, mechanisms, and rewards designed to motivate a target group to join and actively use and engage in activities within the ecosystem. Although prior literature emphasizes the importance of setting the “right” incentives for ensuring participation and engagement within the ecosystem (e.g., Adner, 2017; L. Chen et al., 2022; Valdez-De-Leon, 2019), it remains silent on how to identify what really incentivizes various actor groups and how to orchestrate potentially conflicting or complementary incentives into a set of stimuli able to maximally scale DE participation (Ojala & Lyytinen, 2022; Parker et al., 2017; Pellizzoni et al., 2019). Surprisingly, although both activities are non-trivial and critical for achieving effective participation and engagement within digital ecosystems, they remain chronically under-researched. Our work builds on prior related literature (e.g., L. Chen et al., 2022; Kretschmer et al., 2022; Ojala & Lyytinen, 2022) and introduces a framework demonstrating the process of identifying and integrating incentives into a cohesive system designed to attract both organizations and consumers to an emergent DE.

Consequently, our work makes two valuable contributions to the scholarly literature on the topic. Firstly, our work thoroughly compiles goals and needs crucial for identifying matching incentives to encourage targeted groups to join a DE. This compilation serves as a foundation for discerning DE incentives. Current literature tends to emphasize various incentives like financial rewards, recognition, status, and access to resources (L. Chen et al., 2022; Jacobides et al., 2018), without consistently highlighting the importance of aligning these incentives to goals for optimal motivation. While prior literature offers some examples of stimuli, there is room in the current research landscape for a more structured and comprehensive compilation of needs and goals that can enhance the effectiveness of incentives on their recipients.

Our work offers insights into orchestrating incentives for various actor groups, ensuring a cohesive incentive system. While certain incentives might resonate with specific groups, integrating them into a larger DE framework can sometimes dilute their efficacy. By strategically coordinating these stimuli and considering their potential interactions, we aim to optimize the desired DE participation outcomes, focusing on the collective impact of combined stimuli on their target audience. To date, most studies treat incentives as isolated entities, overlooking potential conflicts or synergies between them. In our work, we account for the fact that stimuli might influence each other’s effects (i.e., can be complementary, conflicting, or unrelated) and thus lead to less optimal outcomes in terms of participation.

In the subsequent sections of this article, we introduce an integrated framework designed to help orchestrate incentives for enhancing participation in DEs. We begin with a discussion on the theoretical underpinnings behind our proposed framework, followed by an overview of our methodology and the key elements of the framework. After presenting the main concepts and elements of the framework, we illustrate its application in the context of an emergent DE in the Smart Living domain. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the advantages and limitations of the proposed framework, as well as potential paths for future research.

Theoretical background

This work relates to various literature streams but particularly to digital ecosystems, incentive system design, organizational strategic management, and consumer technology adoption. In this section, we discuss theories and prior work from the relevant individual streams of literature. We start by elucidating on the digital ecosystems and ecosystem design.

Digital ecosystems and ecosystem design

The information systems (IS) and organization studies (OS) disciplines present various definitions and types of “digital ecosystems” (Bonina et al., 2021; Hein et al., 2020; Isckia et al., 2018; Nambisan et al., 2019; Wang, 2021). Digital innovation ecosystems (Wang, 2021), Internet of things (IoT) ecosystems (Leminen et al., 2012), and platform ecosystems (Parker et al., 2017; Schreieck et al., 2016) are only a few exemplary types of ecosystems mentioned by prior research. These ecosystems, while similar in that ecosystems, represent a community collaborating toward a shared objective (Hein et al., 2020) and exhibit structural and operational differences. Innovation ecosystems, for instance, refer to a community that fosters and facilitates new and disruptive technologies (Wang, 2021). In comparison, the Internet of things (IoT) ecosystems revolve around smart sensors and devices that share data to perform a wide range of (automated) tasks (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2019). Another prominent type of ecosystem mentioned in the literature—platform ecosystems—refers to a community of participants who form around a platform (Parker et al., 2017; Schreieck et al., 2016). In contrast to these ecosystem examples, in this work, we understand DEs in more broad terms—i.e., as dynamic multi-agent environments where agnostic but interconnected species (i.e., technology, digital services, products and platforms, organizations, individual consumers) work loosely together to achieve individual and shared goals (Barykin et al., 2020; Jacobides et al., 2018; Valdez-De-Leon, 2019). This distinction between the various types of ecosystems is particularly important since it reveals differences in scope, emergence, and the set of potentially suitable incentives (Rochet & Tirole, 2003). For a better understanding, we elaborate on the structural differences between platform ecosystems and DEs.

In the context of platform ecosystems, the cornerstone of the ecosystem is the platform itself or a few interconnected platforms. However, the platform(s) is (are) a crucial piece for the value creation process, and the community builds around the platform owner(s) (Hein et al., 2020). This(these) platform(s) facilitate interactions between various participants, often bridging providers and consumers. The platform owner has the power to set the rules of governance for all interactions between actors and benefits from the transactions linked to their platform (Hein et al., 2020). The platform owner drives the platform ecosystem’s inception and keeps a relatively high degree of control as the platform ecosystem evolves and matures. In fact, the platform owner plays a central role in shaping the evolution of the platform ecosystem by curating the product and service assortment as well as the participating providers (Gawer & Cusumano, 2014).

By contrast, in the context of a broader DE concept, the foundational elements of the ecosystem encompass multiple species (e.g., digital tools, platforms, technologies, services, organizations, and consumers) that coexist and benefit from one another (Jacobides et al., 2018). The community builds modularly around delivering novel value or creating new opportunities that can be platform- or technology-agnostic. Modularity refers to the fact that once the ecosystem has formed, no single dominant or governing entity regulates collaborations and ties between actors (Jacobides et al., 2018). Instead, within DEs, participants operate independently and interact with each other based on their own goals and objectives. Although collaboration between actors in DEs is more loose, dynamic, and uncontrollable than in platform ecosystems, the formation of these collaborations and by extension the formation of a DE can be purposefully initiated (Barykin et al., 2020).

In this work, we refer to the strategic establishment of the necessary cornerstones to form an ecosystem as DE design. The DE designers are the companies striving for the formation of the DE. Hence, the formation of an ecosystem starts with the DE designers’ vision and ambition to push for establishing not only a technical infrastructure on which the DE can form but also suitable rules for governing the interactions between the actors in the DE (Floetgen et al., 2022; Hein et al., 2020). The technical infrastructure and suitable governance are equally important for DE’s success (L. Chen et al., 2022; Teece, 2017). Because DEs rely heavily on autonomous agents that contribute to the ecosystems’ value propositions, it is crucial to implement governance mechanisms that enable and coordinate the interactions between actors (e.g., the flow of resources) without losing the advantages of decentralized decisions (L. Chen et al., 2022; Teece, 2017). From an organizational perspective, governance mechanisms can be classified into incentive and control mechanisms (L. Chen et al., 2022). Control mechanisms rely on coercion to ensure that the actors in DEs behave in ways that align with the goals of the DE (e.g., monitoring, sanctions, and penalties for non-compliance). In contrast, incentives rely on motivation and refer to stimuli or benefits offered to actor groups to encourage them to participate in and contribute to the ecosystem voluntarily (L. Chen et al., 2022).

Incentives and their recipients

By definition, an incentive refers to the stimuli or benefit that motivates individuals or entities to take specific actions or behave in a certain way. For incentives to effectively influence their targets, they must resonate with the target’s motivations and self-interest (Adner, 2017; Weber, 2006). Such stimuli spark action by catering to a particular need or objective of the targeted group, whether a consumer or a company. If these groups discern that the incentive aligns with their objectives—essentially, that it resonates with their core goals—they will respond positively (Weber, 2006). On the flip side, a misaligned incentive will not produce the desired outcome. This underscores the idea that incentives are designed to sway entities with agency and defined aspirations. Put simply, the beneficiaries of incentives must have the capacity for intent, ambition, and awareness to identify and pursue specific goals.

In terms of agency, we note that entities like organizations, consumers, and regulatory bodies possess agency in a digital ecosystem, making choices based on their objectives. In contrast, species of a more technological nature (e.g., technology infrastructure, digital services, platforms) lack agency, meaning they operate without conscious and intentional decision-making capacity. Acknowledging this distinction, we deduce that only those with agency within the digital ecosystem (i.e., organizations, consumers, and regulatory bodies) can indeed be influenced by incentives. While incentives must be strategically aligned with these agents’ goals and behaviors, they must be tailored to the distinct nature of the ecosystem in question. As we will briefly discuss in the following, structural differences between various types of ecosystems (e.g., platform ecosystems versus digital ecosystems in the broader sense) require broadly different incentives.

In essence, platform ecosystems promote a degree of centralization (because they revolve around one (or a few) primary platform(s)) (Gawer & Cusumano, 2014), whereas digital ecosystems emphasize decentralization, modularity, and broad interconnectivity (Jacobides et al., 2018). Consequently, the incentives for participation in these two environments will be tailored to these unique ecosystem characteristics and will differ in scale and focus, nature of engagement, or potential benefits. In terms of scale and focus, platform ecosystem incentives are designed to encourage the development of products and services for the focal platform(s) (e.g., through platform-specific developer tools and sharing models) (Gawer & Cusumano, 2014). In contrast, digital ecosystem incentives aim to grow the entire ecosystem (e.g., by educating developers about multiple tools and technologies in the ecosystem). Regarding the nature of engagement, in platform ecosystems, incentives primarily focus on facilitating transactions and direct interactions with the platform (e.g., by providing sellers with analytics tools or discounted transaction fees) (Rietveld et al., 2019). On the contrary, in digital ecosystems, incentives focus more on collaboration (Camarinha-Matos & Abreu, 2007), knowledge sharing (Cresswell et al., 2021), and developing complementary products and services that are agnostic to one technology or platform (Briscoe et al., 2011). Accordingly, in digital ecosystems, the incentives seek to form and establish communities (Immonen et al., 2014), promote interoperability among different platforms, or establish standards that help different ecosystem components work together seamlessly (Hodapp & Hanelt, 2022). Regarding potential benefits and monetization strategies, incentives in platform ecosystems are transactional and will include reduced fees, access to premium features, or specific revenue-sharing agreements. Platform ecosystems also often have a built-in monetization model (e.g., commission-based, subscription fees) with the platform ecosystem provider being a central beneficiary of the platforms’ transactions (Rochet & Tirole, 2003). In contrast, since digital ecosystems are more modular, with no entity exerting too much control (Jacobides et al., 2018), DEs exhibit multiple monetization tactics that are likely to vary across different tools and services. Additionally, incentives in the digital ecosystem are more geared toward long-term objectives and encompass strategic initiatives, partnerships, or investments that enhance the ecosystem’s overall infrastructure, knowledge base, or collaborative potential. Recognizing these distinctions is crucial when determining the optimal incentives to encourage participation in either platform ecosystems or DEs. Furthermore, it is essential to appreciate that individual incentives are components of broader incentive systems which combine and reconcile various incentives into a structure that aligns the interests of various DE groups (Davis, 1993; Kretschmer et al., 2022).

Incentive systems

The design of incentive systems involves considering factors such as the target audience, desired outcomes, and the overall objectives of the system (Kopalle et al., 2020; Kretschmer et al., 2022; Y. Sun et al., 2022; Valdez-De-Leon, 2019). This is necessary for mainly two reasons: Firstly, incentives are not isolated entities that never influence each other. Secondly, incentive systems are not static, one-size-fits-all solutions.

Incentives are not isolated entities

Depending on the target audience, incentives might be independent of each other, complementary, or even contradictory (Adner, 2017; Kretschmer et al., 2022). Complementary incentives are those that align and reinforce each other, while contradictory incentives represent conflicting or opposing ones that can lead to conflicting behaviors between actor groups. In the digital economy, a classic example of conflicting incentives can be observed between tech companies and consumers around data privacy. On the one hand, consumers desire and often demand products and services that prioritize their privacy, wishing to safeguard their personal information and limit data collection (Carl et al., 2023; Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021). This incentive is especially strong due to increasing awareness about data breaches and misuse. On the other hand, many tech companies are incentivized to collect as much user data as possible. This data not only informs their product development and enhances user experience but also becomes a significant revenue source when monetized, either through targeted advertising or by selling to third parties (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021). Such conflicting incentives can pose challenges in achieving a harmonious digital ecosystem, as they push the entities involved in different directions—consumers toward heightened data protection and businesses toward expansive data usage.

Viewing an incentive system as the aggregate of all the incentives intentionally put forth to influence the behavior of various groups and prompt a specific desired action, it is essential to distinguish between conflicting goals and conflicting incentives. While divergent goals between actor groups can foster innovation and yield new value propositions, conflicting incentives—those that induce behaviors that neutralize each other or collectively lead to undesired outcomes for the ecosystem’s overall participation—should be approached with caution.

Incentive systems are not static

The dynamic nature of DEs (Adner, 2017) implies that incentive systems are not static, one-size-fits-all solutions. Rather, incentive systems must be flexible and able to evolve with the DE to fit the ecosystems’ current life cycle phase (Panico & Cennamo, 2022). Under the premise that DEs do not just “appear” but develop and evolve over time, literature on DEs distinguishes four life cycle phases: inception, growth, maturity, and renewal (Isckia et al., 2018; Teece, 2018). Each life cycle phase is linked to slightly different challenges, the incentive system needs to be aligned with (Panico & Cennamo, 2022). During inception, for instance, participants must imagine and understand the new opportunities that the DE affords and view the new ecosystem as appealing (Isckia et al., 2018). Hence, at this initial stage, DE designers might want to focus on attracting industry leaders and early adopters (Khanagha et al., 2022) who can then serve as advocates, demonstrating the DE’s innovativeness and potential to other organizations. During growth, attracting outsiders and broadening the user base are vital to achieving a critical mass of active participants (Isckia et al., 2018; Teece, 2017). Hence, during the growth stage, DE designers’ focus might be on the exponential growth of the DE’s participant base (Sebastian et al., 2020). Once the ecosystem possesses the critical mass to unlock its full potential, the DE reaches maturity, and participants are now starting to explore business opportunities within other ecosystems (Isckia et al., 2018; Teece, 2017). If DE designers do not counter the transition of ecosystem partners and value to competing ecosystems, the DE will shrink and eventually disappear. Hence, during this post-maturity phase, DE designers might seek ways to rejuvenate the ecosystem (Isckia et al., 2018; Teece, 2017). Therefore, at this juncture, DE designers might seek to attract new and highly innovative actors that can help the ecosystem penetrate other industries or find new and innovative ways for value creation. Given the varying strategic emphases that accompany each stage of an ecosystem’s life cycle, it becomes imperative to re-align incentives within the system when deemed necessary (X. Sun & Zhang, 2021).

To sum up, designing incentive systems for DE participation requires designers to comprehensively understand the expectations, goals, and needs of the target audience (actor groups) when joining and participating in the DE. Furthermore, designers must have access to suitable strategies and mechanisms that allow them to orchestrate incentives into an incentive system—i.e., one able to attract companies and consumers alike to join and participate in the ecosystem. It is important to note that companies join and participate in DEs primarily by playing an active role on the supply side of the ecosystem (e.g., by co-developing products and services). In contrast, consumers are typically on the demand side of the ecosystem (e.g., by adopting and using the products and services provided in the ecosystem) (Hein et al., 2020). Thus, we can draw on the literature stream on organizational strategic management to structure and explore companies’ expectations and goals when deciding to join DE. To understand consumers’ needs and goals when adopting and using the products and services provided in the ecosystem, we can draw on the technology adoption literature. Below, we discuss both streams of literature in more detail.

Organizational strategic management literature

In our case, the organizational strategic management literature provides a framework to analyze how companies plan and make strategic decisions, such as the decision to join a DE. Companies often join DEs to achieve specific business goals, such as expanding market reach or leveraging new technologies for innovation. The organizational strategic management literature provides the necessary insights and tools to identify these goals and how they align with the broader strategic objectives of the company. As previously noted, the decision to participate in DEs, akin to other strategic company choices, depends on the anticipated value from the ecosystem. However, just as quantifying the value and impact of IT in organizations is complex, so is assessing the precise benefits of DE participation. Delving deeper into this argument, existing literature indicates that technology and IS investments can yield tangible and intangible returns, which might only manifest in the mid- to long-term. Directly correlating these investments with organizational profits remains difficult, both in retrospective and, even more so, in predictive evaluations (Rosati et al., 2017; Tallon & Kraemer, 2007; Tallon et al., 2020). Committing to a digital ecosystem can parallel IT investment decisions, for instance, in terms of risks, long-term commitment, and potential need for alignment with the organization’s broader strategic goals. Also, similar to IT investment decisions, the choice to enter a DE potentially yields tangible and intangible results, whose realization may vary over time, making their upfront quantification notably challenging.

Motivated by the challenge of capturing less tangible benefits such as improved customer service (Volberda et al., 2021) or new collaborations and complementarities that would not form outside the DE (Jacobides, 2019), scholars (e.g., Martinsons et al., 1999; Milis & Mercken, 2004; Shen et al., 2022) suggest using the well-established balanced scorecard (BSC). Originally developed by Kaplan and Norton (1992), the BSC aims to complement the financial perspective on business performance with the non-financial perspective. Applied to technology projects and decisions, the BSC is also useful for developing metrics reflecting the tangible and intangible benefits of technology implementations (Martinsons et al., 1999; Shen et al., 2022). Because “the metrics used in a balanced scorecard framework are aligned to the company’s strategy and business aims”(Milis & Mercken, 2004, p. 94), the BSC model allows managers to adopt a comprehensive view on technology investments while also serving as a map for navigating the strategic goals of the company (Milis & Mercken, 2004). In particular, the BSC allows organizations to measure their intangible assets, such as customer relationships, innovative products, services, technology, knowledge, and the organizational structures that provide a company with a competitive advantage (R. S. Kaplan & Norton, 1992, 2001). Accordingly, the BSC has practical relevance for strategy and focuses on financial and non-financial aspects, short-term and long-term strategy, and internal and external business measures (Wu, 2012).

Specifically, the BSC takes on four perspectives: a financial perspective, a customer (or market) perspective, an internal process perspective, and a learning and growth perspective. Following Kaplan and Norton (1992, 2001), from a financial perspective, companies focus on their economic and financial health (e.g., profitability and value creation of the organization) (Fischer & Himme, 2017; Kliestik et al. 2020). From a customer perspective, companies seek to understand their market performance regarding their customer relationships (e.g., customer satisfaction, retention, churn) and market share (Kamalaldin et al., 2020; Krizanova et al., 2019). From an internal process perspective, companies seek to understand the efficiency and effectiveness of their operations and processes (H. Chen et al., 2021). Ultimately, the learning and growth perspective encompasses factors crucial for fostering continuous learning, improvement, and adaptability within the company—e.g., employee training and development, knowledge management, innovativeness, and organizational culture (Kimiloglu et al., 2017).

We use the BSC model as a structured blueprint for exploring companies’ goals and expectations when deciding to join DE. To now turn to the consumers’ side and delve into the goals of this group when deciding to join a DE (specifically, to use the offerings of the DE rather than alternative options), we draw on the technology adoption literature. Consulting the technology adoption literature, particularly its theories, is fitting, as these theories have traditionally examined the factors influencing individuals’ decisions to accept or reject new technologies and products.

Technology adoption literature

Research on technology adoption is one of the most mature streams in IS literature (Ho et al., 2020). It entails theories concerning individuals’ pre- and post-adoption behaviors (Mishra et al., 2023). While pre-adoption theories focus on explaining individuals’ intentions to adopt, post-adoption behaviors focus on what drives usage continuance. Given that we seek to explore and structure both—consumers’ needs and goals when initially joining the DE but also their needs and goals in relation to continuous participation in DE (i.e., continuous use of the ecosystem products and services)—our work relates to both streams of literature within this corpus of research. Within the technology pre-adoption literature, we mainly refer to two of the well-established adoption models: Davis’ (1989) technology adoption model (TAM) and Venkatesh et al.’s (2003) unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). According to TAM, technology acceptance is mainly driven by individuals’ attitudes toward the technology, which in turn is shaped by the individuals’ perception of the technology’s usefulness (PU) and ease of use (PEoU) (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh et al., 2003). PU describes to which degree individuals think a particular technology can fulfill predefined goals. PEoU reflects individuals’ perception of how effortless a technology’s usage might be (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh et al., 2003). TAM has served as a foundation for various other research models for technology adoption. The UTAUT, for instance, posits that technology acceptance and use are determined by four constructs: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions (Venkatesh et al., 2003). While performance expectancy refers to individuals’ beliefs that using the target technology will advance their goals (i.e., it is equivalent to PU), effort expectancy represents the same as PEoU. However, social influences (also referred to as “subjective norms” (Brown et al., 2010)) relate to individuals’ beliefs that adopting technology will enhance their status within a relevant peer group (Maruping et al., 2017). Extant literature corroborates the link between important actors and individuals’ technology adoption intention (Brown et al., 2010). This link is compelling for novices (i.e., individuals with no prior experience with the target technology) and within the work-related context when important external others (e.g., supervisors, colleagues) can exert some sort of pressure on the potential adoption candidate (Maruping et al., 2017). Finally, facilitating conditions refer to objective factors that make technology use possible. Such factors include technical and organizational support (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Within the technology post-adoption literature, our work relates to Bhattacherjee’s (2001) expectation-confirmation model (ECM) and Liao et al.’s technology continuance theory (TCT). In both models, individuals’ continued technology use is strongly driven by consumers’ satisfaction with the technology, which again depends on factors such as PU and PEoU (Liao et al., 2009). With PU and PEoU influencing both the technology pre- and post-adoption, while other factors might influence only consumers’ satisfaction with the technology (post-adoption), we suggest distinguishing between “first-tier” drivers of adoption and use (e.g., PU, PEoU) and additional “second-tier” drivers of continuous use (i.e., any factors that can increase satisfaction in the post-adoption phase).

We combine the previously discussed streams of literature to develop a framework for designing incentive systems for DE participation. Based on the literature on digital ecosystems and ecosystem design, please remember that DEs are dynamic multi-agent environments where diverse but interconnected species—ranging from technology, digital services, products, and platforms to organizations and individual consumers—operate in a loosely coupled manner. Their interaction dynamics aim to realize unique and collective goals, reflecting the intricate and often symbiotic relationships within these digital realms. The literature on incentives provides the foundational rationale for our framework. Incentives are stimuli crafted to motivate specific actions or behaviors. These incentives work only with entities that possess the necessary agency and conscious decision-making ability to be swayed toward a particular behavior. In the context of DEs, not all entities have the necessary agency; our study recognizes that besides regulatory or governmental bodies, only the consumer and organizational species possess agency. Building on this, we delve into incentive systems literature, emphasizing that incentives do not operate in isolation. They are components of intricate systems where individual incentives interact and potentially influence each other. An effective incentive system, therefore, necessitates a careful orchestration of these incentives, ensuring that their collective influence yields the most desirable outcomes in terms of ecosystem participation. Yet it is important to acknowledge that organizations and consumers are two different species that are driven by a different set of goals. From the realm of organizational strategic management, we adopt insights from the BSC model. Given its structured approach to exploring and articulating corporate objectives and aspirations, the BSC model serves as our guiding blueprint for exploring companies’ goals and expectations when deciding to join DE. Lastly, our framework is also informed by the technology adoption literature, which is pivotal because technology acceptance theories shed light on the nuances that drive individuals’ decisions around embracing the offerings of the DE over alternative offerings.

By blending the insights from all these research dimensions, our framework aims to offer a comprehensive, nuanced, and actionable guide for devising effective incentive systems tailored for the DE landscape. Having laid out this foundation, let us transition into the structured process through which we developed the framework.

Methodology for developing the framework

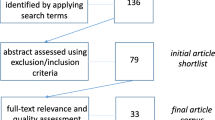

For the development of the framework, we follow various scholars’ insights on theorizing and developing (integrated) IS frameworks (e.g., Baird & Maruping, 2021; Burton-Jones & Volkoff, 2017; Hassan et al., 2022; Maxwell, 2012; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Specifically, we design our framework in a multi-step approach (see Fig. 1). First, we conducted comprehensive literature reviews (step 1, Fig. 1): Initially, we performed a systematic literature review approach employing a keyword-driven search (consumers: “digital AND (preferenc* OR nee*)”; companies: “compan* AND “strategic goals””). For consumers, we focused on the best-ranked publications in IS research (VHB A + , A, and B), and for companies, we conducted a broader search, capturing the online library EBSCO. The search led to 1032 (consumers) and 1336 (companies) results. In the first step of assessing the title and abstract, we retained 112 (consumers) and 386 (companies) publications. Facing high exclusion rates in both steps of the paper analysis due to the required transferability of results to the context of DEs, we received 10 relevant publications for consumers and 9 for companies. Thus, we performed more explorative further searches employing multiple backward and forward search steps as well as more explorative search on received goals and needs and regularly updated the search, leading to a total of 34 publications regarding consumers’ needs and 32 covering companies’ goals. To sum up, the aim of this literature review was to capture the current state of related work on (i) companies’ expectations and goals concerning DE participation, (ii) consumers’ expectations and needs concerning DE participation, and (iii) potential set of strategies and mechanisms to orchestrate individual incentives into incentive systems. The literature reviews capture the current state of related work and allow us, in a second step, to aggregate knowledge from prior research efforts into one comprehensive framework (Baird & Maruping, 2021; Okoli & Schabram, 2010). We follow the established propositions by Kitchenham et al. (2009), which ensure that synthesizing the extracted research findings informs and guides practitioners in a structured and comprehensive manner (Kitchenham et al., 2009; Snyder, 2019). Besides, the literature reviews also serve as a basis to further aggregate and cluster previous research based on predefined criteria, informing the conceptualization of a (new) theory construct (Paré et al., 2015; Snyder, 2019).

In a second step, the insights from prior literature were aggregated and synthesized through a DE-specific lens (step 2, Fig. 1), however interacting with the first step (literature review) to adapt the process accordingly. The DE-specific lens enables us to account for idiosyncratic characteristics of DEs, such as the collaborative value creation in a coopetitive environmentFootnote 1 (Lettner et al., 2022), particularly for DEs. For instance, in DEs, value creation occurs through collaboration (i.e., via common business practices, interoperability between products and services, shared data spaces, and knowledge transfer). Hence, the organizational goals concerning DE participation might not include only goals such as improving the company cost structure (R. S. Kaplan et al. 2004; Wu, 2012) but also goals such as creating new value (i.e., products and services) that otherwise would not be possible to develop. At the same time, organizational goals that might be important in other contexts (e.g., financial transparency (S. Lee et al., 2021)) might play no significant role in the context of DE participation.

We compiled a preliminary framework based on the aggregated insights from prior literature (step 3, Fig. 1). To this end, we use the BSC to structure and document companies’ expectations and goals concerning DE participation. Analogously, we structure and document consumers’ expectations and goals concerning DE participation by distinguishing between first-tier (must-have expectations and goals to join and continuously participate in the DE) and second-tier factors (optional factors that can increase consumers’ satisfaction with the offerings of the DE and thus support continuous participation).

The preliminary version of the framework was validated in two workshops with domain experts working on a joint research project (step 4, Fig. 1). The research project aims to design and develop the necessary components for a DE in the Smart Living domain. The workshops were conducted with six domain experts with different backgrounds and research foci: Three participants represented the R&D departments of leading global suppliers of smart home, mobility, and consumer goods technology. One participant represented the association of electric and consumer goods. Another participant represented an SME supplying smart home solutions. Finally, two participants work for research entities researching digital (services and consumption) ecosystems. In the first workshop, the experts discussed and chose the most relevant companies’ organizational goals in relation to DE participation. In the second workshop, the discussion revolved around the most critical consumer needs concerning DE participation. Both workshops resulted in a curated list of company goals and consumer needs most relevant concerning DE participation. Finally, we combined all findings in one framework to design DE participation incentive systems.

Framework for designing incentive systems for DEs

Figure 2 visualizes the proposed design framework. It consists of three building blocks (i.e., identify incentives, combine incentives into a system, and incentive system realignment) and three key elements (i.e., (i) company goals, (ii) consumer needs, and (iii) orchestration mechanisms). Subsequently, we discuss each building block individually, as they indicate how to use our framework.

First building block: Identify incentives

The first building block of the framework suggests identifying the incentives for each of the targeted actor groups—i.e., in our context, companies and consumers—by analyzing these actors’ expectations, goals, and needs when joining and participating in DEs. Only once designers document companies’ and consumers’ needs and expectations in relation to DE participation can they derive incentives that will be effective for each of the individual target groups. For these activities, designers can use a range of methods: Expert interviews and Delphi studies, for instance, are suitable for documenting companies’ goals and potentially deriving applicable incentives for companies. Analogously, expert interviews, focus groups, or consumer surveys are helpful to gather consumers’ needs and derive suitable incentives for this group. To support these activities, our framework offers concrete support by providing a comprehensive set of goals and needs that companies and consumers have concerning their DE participation decisions.

As mentioned in the previous section (the “Methodology” section for developing the framework), these company and consumer goals were derived from prior literature. We first present the (i) company goals along the four perspectives proposed by the BSC. From a financial perspective, companies focus on economic and financial status. There are various ways to increase the value of a company through strategic actions. Common measures are, for example, the development of a new business field, the acquisition of a company, or a strategic realignment. Short-term profits should be subordinated to long-term successes (Rappaport, 2006). Thereby, investors closely monitor revenue, profitability, and expected cash flows (R. S. Kaplan & Norton, 1992). Additionally, investors also monitor the decisions about adopting new technological developments.

In general, DE participation can directly or indirectly improve various key financial performance indicators. For instance, DEs require a certain degree of homogeneity regarding common technical standards (Wareham et al., 2014). This technical homogeneity creates cost reductions and risk-sharing opportunities when developing new products and services (Gawer & Cusumano, 2014). Furthermore, because various technology components and other assets can be exchanged and used across DE partners, DEs also open new opportunities for asset usage (Subramaniam et al., 2019). Such assets include data, IT infrastructure, algorithms, and other software components. While some of these assets (e.g., data) might find only limited application in the organization they originate from, such assets can be important for other ecosystem partners (Schneider & Kokshagina, 2021). If the ecosystem disposes of the necessary mechanisms to remunerate the provision of assets to other DE partners, assets that were not previously used can offer new sources of revenue. Cost reductions, risk sharing, and better asset usage can improve various key financial performance indicators such as profit margin or returns on investment (Gamayuni, 2015; Romanova et al., 2021). Simultaneously, by developing and distributing novel products and services that would not have been possible without collaboration within the DE, companies can increase their turnover and market value (Redjeki & Affandi, 2021; S. Zhang et al., 2019).

From a customer perspective, companies are concerned about gaining new and retaining existing customers. Although customers have always been important to companies, nowadays, in the digitalized world, they are even more powerful and essential than ever (S. M. Lee & Lee, 2020; Mihardjo et al., 2019). As digitization is pervasive in everyday life and switching to competing products and services is easier than ever (Leimeister et al., 2014), gaining and retaining new customers for a company are necessary for success. DEs support this essential condition in various ways. For instance, DE participants can collaborate to enjoy synergy effects for various organizational functions (Subramaniam et al., 2019). While a collaborative development of products and services to create better value for the customer is obvious, companies in a DE can also leverage ecosystem-wide shared resources and assets (e.g., shared data spaces, algorithms, components, and knowledge). By sharing such infrastructural elements and assets, participating companies can improve other key areas such as marketing, user experience, and process optimization (Helo et al., 2021). For instance, by building a shared ecosystem data space, various positive trickle-down effects might occur: First, a DE’s shared data space enables companies to capture and extract new intelligence on customer needs and preferences (Subramaniam et al., 2019) that otherwise would remain concealed. Second, additional customer insights can strengthen organizations’ agilityFootnote 2 and the capability to satisfy consumers’ needs. Third, through a better product and service fit with consumer needs, organizations can gain new customers or increase the satisfaction and loyalty of existing customers (H. Sun et al., 2020).

From an internal process perspective, DE participation can bring a range of benefits that improve the operational inner workings of companies. Similar to shared technological standards that ensure interoperability between the components provided by different DE partners, DE participation can require that various internal processes across DE participants are standardized or harmonized (Aulkemeier et al., 2019; Helo et al., 2021). Although implementing changes to extant processes represents an investment on the side of the DE partners, it can have significant benefits for the overall performance of the ecosystem. After all, by standardizing or harmonizing processes and forcing various partners to adopt specific ecosystem processes, outputs of the joint work between DE partners are standardized enough to ensure a high quality of solutions and applications (Wareham et al., 2014). Additionally, with aligned internal processes across participants, the flow and sharing of resources (e.g., data assets, knowledge) between DE participants is optimal and can have various benefits (L. Chen et al., 2022): For instance, the flow of diverse domain expertise across DE participants might enable some companies to adopt technological innovations faster than otherwise (Gupta et al., 2019). Similarly, through the governance entity of the DE, which sets the rules of the game for all participants in terms of legal (e.g., data protection, data security) and social responsibilitiesFootnote 3 of business activities, DEs ensure that all companies within the ecosystem comply with the current rules (L. Chen et al., 2022). While these advantages might not be of enormous importance for bigger organizations, they could significantly benefit smaller and middle-sized enterprises (SMEs). For SMEs, process standardization or harmonization across DE partners enables them to profit from key organizational functions (e.g., distribution channels, marketing) and other synergy effects.

Typically, synergy effects allow companies to generate more value than they would have alone (Yu & Wong, 2014). Such synergy effects occur from resource sharing or resource integration (Y. Xu et al., 2023). In an ecosystem, SMEs can enjoy synergy effects, for instance, from sharing resources such as legal, financing, or technological skills (Wasiuzzaman, 2019). Smaller companies cannot usually afford (a large) legal department. However, within a collaborative digital ecosystem, SMEs could set up a joint legal department with several other participating SMEs and start-ups. Such setups and collaborations between ecosystem participants can improve the cost and asset structure (Wasiuzzaman, 2019). Suppose ecosystem participants can share assets and follow the main notion of the sharing economy (i.e., use instead of own), in that case, ecosystem participants can also enjoy a better cost and asset structure. In addition, aligned processes across partners can also mean increased synergy effects that yield increased productivity. After all, aligned business and technical processes and standards ensure that combining various application components, modules, and solutions into one intelligent offering is technically and operationally possible without compromising on quality (Hein et al., 2019).

Ultimately, from a learning and growth perspective, companies focus on creating sustainable growth (Masli et al., 2011). As competition between companies increases, technological advancements put companies additionally under stress while consumer needs shift. Hence, it is more essential than ever that companies become learning entities (Garvin et al., 2008). The goal is to enable a company’s employees to cultivate innovations (Quezada et al., 2019), promote open discussions, and develop a holistic and systematic way of thinking. The result of this process is a company that can react faster and better to unexpected changes than its competitors.

The extant body of literature has repeatedly recognized the importance of innovation and knowledge for sustainable growth (Vaz and Nijkamp, 2009). Hereby, knowledge refers not only to the available intelligence within a company but also to a company’s ability to assimilate and use the knowledge from external sources. Although the importance of the internal versus the external knowledge source might vary with company size and industry, both knowledge types are essential for sustainable growth (Vaz and Nijkamp, 2009). For SMEs, for instance, the external source of knowledge in the form of lessons learned from similar companies and endeavors can help companies minimize risk (Manica et al., 2017; Vaz and Nijkamp, 2009). Similarly, intel on the failure of others can help companies discover the changes and potential for improvement needed to avert failure (Liang, 2015). In contrast, internal knowledge can help companies improve their products and services and develop new and innovative ones. While such internal knowledge can be honed through professional training (Cao et al., 2015; Liang, 2015), it can only be retained in the company through increased employee satisfaction (Liang, 2015; Quezada et al., 2019; Wu, 2012) and low personnel turnover (Wu, 2012). DE participation is an excellent opportunity for companies to tap into external knowledge sources and profit from lessons learned by other partners (Weissenberger-Eibl & Hampel, 2021). Similarly, it can offer a great opportunity to build new internal knowledge and skills, offer employees new challenges, and foster a culture of innovation (Volberda et al., 2021). Figure 3 summarizes company goals relevant to DE participation.

Besides companies’ goals concerning DE participation, the second important element in our framework is (ii) consumers’ expectations and needs when joining DEs. Analogous to organizations, particularly companies’ goals concerning DEs, individuals can also display many needs and preferences when deciding to use DE-based offerings over single-provider products and services. Such needs and preferences can be related to the function of products and services the DE enables or other DE-specific benefits—e.g., whether the DE empowers individuals to be both consumers and value contributors within the ecosystem (Lettner et al., 2022; Valdez-De-Leon, 2019). Although successful DEs need to generate value for their users and produce offerings that match consumers’ needs (Valdez-De-Leon, 2019), our understanding of consumers’ needs and expectations when joining DEs remains very sparse.

Traditionally, researchers and practitioners elicit and analyze consumer needs and preferences to inform the design and marketing of (digital) products and services (Chapman et al., 2008). Marketers, for instance, conduct preference studies mainly for articulating commercialization-related goals (Chapman et al., 2008). Design engineers exploit consumer preferences to create and develop consumer-orientated products. In the human–computer interaction (HCI) discipline, consumer needs and preferences ensure good usability of products and services (Chapman et al., 2008). Although various fields leverage intelligence on customer needs and preferences to achieve different goals, they have in common that customer needs are investigated concerning features of specific products and services. Because in this framework, we are interested in a higher abstraction level—i.e., DE participation—consumer needs result from the inherent properties and benefits of digital ecosystems.

DEs are complex structures in which value creation is dynamic and possible only through the collaboration of several partners and species (Subramaniam, 2020). In this context, the partners within the DE are interdependent. Partners share resources, particularly data, which is essential in value creation (Hein et al., 2020). In a DE, partners can build intelligent services and create new products and solutions by using and combining components and products developed by another partner (Hein et al., 2020). Furthermore, partners can use the data generated by the devices and systems provided by one partner to improve and develop their offerings further (Schneider & Kokshagina, 2021).

On the bright side, within this dynamic and complex environment, DE partners can create personalized and context-aware products and services that fit consumers’ needs better than ever (Hein et al., 2019). Furthermore, through collaboration and recombining various DE components and resources, the DE allows companies to implement and issue new products and services faster and cheaper than before (Hein et al., 2019, 2020). Besides, because DEs require a certain degree of homogeneity in terms of technical standards (Wareham et al., 2014), offerings within a DE are typically interoperable and (re)combinable, leading to new products and services (Hein et al., 2020). An additional advantage of DEs is their ability to engage users in the (co-)creation of new DE offerings (Sussan & Acs, 2017). On the downside, however, the complex and dynamic environment of DEs can exacerbate challenges that a digitalized, highly recombinant, and interconnected world can bring. For instance, due to the importance of data in the value creation process, DEs can exacerbate extant privacy and opacity challenges (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2022). Moreover, when it comes to the collection and processing of data, companies and consumers have conflicting interests (Royakkers et al., 2018). While companies see data as a critical production factor and seek to amass as much data as possible, consumers would like to be informed and in control of what happens to their data (Carl et al., 2023; Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021).

The importance of data privacy and security is a widely discussed and multi-faceted research topic in IS research (e.g., Acquisti & Grossklags, 2005; Adjerid et al., 2018; Bélanger & Crossler, 2011; Hann et al., 2007; Park et al., 2018). Its importance is also reflected in various data privacy and security regulations and directives such as the European General Data Protection Regulation or the OECD Guidelines for Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021). According to the OECD (2013) guidelines, for instance, privacy and data security should consider eight main principles: (1) data collection should be limited, (2) collected and stored data quality should be high (e.g., accurate and up-to-date data), (3) purpose specification for data collection, (4) limited data use to consented purposes, (5) appropriate security safeguards for storage and processing, (6) openness or transparency about data processing practices, (7) individual participation should be possible to correct or add and delete data, and (8) accountability for all collected and processed data. Implicitly, sound practice principles for data security and privacy emphasize the importance of transparency within the DE.

Research on transparency in complex networks suggests that companies can pursue transparency at different strategic and operational levels. For instance, transparency can occur by disclosing information about their pricing strategies (e.g., Granados & Gupta, 2013) or data processing and monetization practices (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2019; Turilli & Floridi, 2009). Companies can also implement transparency of their processes and governance structures by using certifications—a widely adopted institution-based mechanism to increase consumers’ trust (Carl & Mihale-Wilson, 2020). Finally, transparency can also mean making the data flow within networks traceable and accountable (Mihale-Wilson, 2021). After all, as DE offerings become more complex and surge from recombining various components and resources of the DE, it becomes increasingly complicated to track and understand data flows and how data is processed (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2022; Royakkers et al., 2018). As such, it also becomes almost impossible to trace and handle product safety and liability responsibilities, enforce customer rights, and settle disputes (Carl et al., 2023; Mihale-Wilson et al., 2022).

In general, product safety describes the degree of potential risks and injuries due to the handling and use of products (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021). At the same time, liability relates to the actions of product or service providers in the event of injury (Daughety & Reinganum, 1995; Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021). While it is feasible in the physical world to identify the source of most injuries, in the interconnected and recombinant world of DEs, finding the definite cause of injuries can be impossible. Additionally, since consumers of digital offerings may suffer physical and psychological harm that is not necessarily visible at first glance, product safety and liability in DEs are much more complicated than in the analog world (Carl et al., 2023; Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021).

Notably, the opaque nature of DEs can cover the use and flow of data, the recombination of software components, and the overall availability of offerings within the DE (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2022). Through the recombination of components, data, and solutions, DEs enable the development of many offerings (Hein et al., 2020). Suppose the number of available offerings becomes unmanageable. In that case, successful DEs require ways and tools (e.g., a recommendation engine) to help users choose the online offerings that best suit their needs (Schneider & Kokshagina, 2021). Therefore, such tools and mechanisms need to be trustworthy and inclusive. Trustworthiness refers to matching offerings with consumer needs and preferences while putting customers’ economic needs first. Inclusivity refers to DE offerings being accessible and usable for different consumer segments (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021).

The need for trustworthiness stems from companies and consumers having conflicting economic interests. This tension between consumers and companies has been observed and analyzed in many contexts, such as regarding interoperability of technical standards (e.g., Lewis, 2013), pricing strategies (e.g., Weisstein et al., 2013), and recommendation systems (e.g., Xiao & Benbasat, 2011). Despite the various foci and research questions that existing studies investigate, they ultimately indicate that protecting consumers’ economic interests can pay off in the long run (Weisstein et al., 2013).

The requirement of inclusivity stems from the documented fact that inequalities in access or knowledge on how to use technology can have adverse human, social, and financial capital disadvantages for various groups (e.g., Agarwal et al., 2009; Hsieh et al., 2011; Park et al., 2018). Therefore, it is essential to distinguish between accessibility and technology literacy issues. While accessibility refers to whether DE offerings are accessible to everyone, technology literacy refers to the fact that participation in DEs will also require—to some extent—the knowledge needed to use technology (Park et al., 2018) effectively. Only if consumers possess the knowledge to use various DE offerings, they will succeed in leveraging the value added of these offerings and thus continue to use them actively (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2021). Following this logic, to ensure participation on the consumer side, successful DEs need to bestow consumers with the knowledge needed to benefit from the DE’s offerings.

To conclude, we note that digital consumers nowadays “expect to be very well informed, spoiled, and empowered” (Granados & Gupta, 2013, p. 637). Against this background, customer needs concerning DE participation entail functional and usability-related requirements and mechanisms for transparency, consumer empowerment, inclusion, and accountability. Some individual needs are more likely to be linked to mandatory conditions that must be met to participate in DE at all (Subramaniam, 2020). In contrast, others might not be prohibitive and influence the chances of participation only partially (see Fig. 4). With that in mind, we draw on the insights discussed in the theoretical background section and classify functionality (e.g., perceived usefulness, reliability) and usability-related needs (e.g., perceived ease of use, required data privacy, and security levels) as “first-tier” mandatory conditions for participation. In contrast, we can classify individual needs linked to consumer empowerment, inclusion, and accountability (e.g., transparency, consumers’ economic interests, data security, and privacy exceeding legal requirements) as “second-tier” conditions for DE participation.

Second building block: Combine incentives into a system

Incentive systems combine and reconcile various incentives into a structure that aligns the interests and behaviors of different actor groups of the ecosystem (Davis et al., 1992; Kretschmer et al., 2022). This is essential since the individual incentives between actor groups or within an actor group might be independent of each other, complementary, or even contradictory (Adner, 2017). Thus, to maximize the incentive system’s effect on its target audience, designers need to “orchestrate” incentives in an incentive system. In other words, they need to carefully pick, combine, and coordinate the various incentives within a cohesive and integrated set (i.e., “incentive system”) that work together to achieve their set goal. Orchestration ensures that the incentives are strategically aligned, properly balanced, and effectively deployed to maximize their impact and achieve the intended objectives of the incentive system (Panico & Cennamo, 2022). Again, to support this process, our framework proposes four (iii) orchestration mechanisms for incentives: prioritizing (Jahantigh et al., 2018; Treiber et al., 2023; Verma et al., 2022), coordinating (Gkeredakis & Constantinides, 2019; Meyerhoff Nielsen & Jordanoski, 2020), aligning (Makkonen et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2019; Murthy & Madhok, 2021), and monitoring and re-tuning (Martin et al., 2019; Panico & Cennamo, 2022). Analogous to companies’ and consumers’ expectations and goals related to DE participation, the orchestrating mechanisms from the framework were derived from prior literature.

Prioritizing accounts for the heterogeneity and multitude of options (in our case, incentives) that need to be considered (Jahantigh et al., 2018). Further, it accounts for the evolving life cycle of the DE and the fact that various stages of the ecosystem require different emphases (Panico & Cennamo, 2022; X. Sun & Zhang, 2021)—i.e., for instance, certain companies and consumer segments may become the focal points for incentives at different times. Besides, prioritizing also refers to prioritizing the company goals (Jahantigh et al., 2018) and consumer needs (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2019; Shah et al., 2006) following the preferences of the targeted groups. The coordination mechanism accounts for the fact that the various company goals and consumer needs are likely interdependent (e.g., contradictory or complementary) (Gkeredakis & Constantinides, 2019). Because contradiction between goals and needs requires a trade-off that will render the incentive system less effective (Q. Zhang & Sun, 2023), finding ways to reconcile and broker between contradicting company goals and consumer needs is essential. In contrast, logic dictates that incentive designers must create strategies that meet individual goals and synergize with others, generating the necessary momentum to draw a broad spectrum of companies and consumers to the digital ecosystem. The aligning mechanism is a prerequisite to ensure the maximally desirable participation outcome (Makkonen et al., 2022). After all, incentives can only trigger a desired action if they concur with the incentive recipient’s specific need or goal (i.e., consumer or company) (Adner, 2017; Weber, 2006). If the incentive does not fit with the intended recipient’s goals, the incentive will not be effective and will not lead to the desired behavior (Adner, 2017; Weber, 2006). Ultimately, the monitoring and re-tuning mechanism ensures that the incentives system continues to be effective over time. Since DEs are dynamic environments that evolve, incentive systems must be monitored and re-tuned whenever necessary (Panico & Cennamo, 2022).

Table 1 provides an overview of the discussed orchestration mechanisms and names exemplary methods that can be used to leverage each respective mechanism. For instance, to prioritize incentives for companies (i.e., identify top priority incentives), designers can conduct interviews with companies appertaining to the targeted companies group. Then, if the top priority company and consumer incentives are contradictory, designers can broker between these incentives based on the input from expert workshops and expert interviews.

Third building block: Incentive system realignment

Following the arguments presented earlier, incentive systems cannot be static and should evolve with the changing conditions of each DE life cycle. As discussed previously, depending on whether the DE is in its inception, growth, maturity, or renewal phase (Isckia et al., 2018), the incentive system must address the respective life cycle challenges. During the inception phase, for instance, DE designers might want to attract industry leaders and early adopters. At later stages, such as the growth phase, DE designers’ focus might be on the exponential growth of DE’s participant base. Similarly, once the first-tier consumer needs are satisfied, incentive systems should consider the second-tier needs most important for the biggest group of consumers that the DE intends to appeal to. Accordingly, it is essential to monitor the goals of the incentive system and, if necessary, re-tune the system to be effective and continuously attract the DE actors it seeks to attract (Panico & Cennamo, 2022). To this end, designers can employ the previously stated orchestration mechanisms to both monitor and re-tune existing incentive systems. We detail the process of this “realignment” within the system in the Use Case section of this study, where we provide a comprehensive guide on the practical application and expected outcomes of such strategic adjustments.

Case study: Applying the framework to a DE in Smart Living

To highlight the practical usefulness of our proposed framework, we present its application in a real-world scenario: an emerging digital ecosystem in the Smart Living space. This illustration is underpinned by expert interviews and a survey conducted to assess the robustness and relevance of the framework. Before delving further into the case study, it is pivotal to elaborate on the concept of Smart Living.

Advancements in fundamental technologies, such as cloud computing, artificial intelligence, or the Internet of things, gain ever-increasing traction and abet a new generation of digital products and services (Hosseinian-Far et al., 2018; Mihale-Wilson et al., 2022). Along with these advancements, scholars and practitioners expect a significantly growing importance of the Smart Living domain in the upcoming years (Makkonen et al., 2022; Murthy & Madhok, 2021). In essence, the Smart Living concept refers to weaving technology into our daily lives to improve convenience, efficiency, sustainability, and the overall quality of life (Hosseinian-Far et al., 2018; Jiménez et al., 2014). Among others, Smart Living envisions more convenience and higher quality of life by streamlining and automating various tasks to make routine activities more efficient (Bauer et al., 2020). With various daily activities being automated, consumers might have less stress and more free time to do whatever they love (Mihale-Wilson et al., 2017). Besides automation of tasks, Smart Living also envisions that smart services and systems can support consumers to lead healthier (e.g., through monitoring and recommending dietary and sports activities) and more sustainable lifestyles (e.g., through optimized energy consumption and waste reduction) (Bauer et al., 2020; Cimmino et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2019). Although desirable from a welfare and well-being point of view, the materialization of the Smart Living promise requires a high level of interoperability and cooperation between actors (Jiménez et al., 2014).

To achieve the cooperation and interoperability needed to materialize the Smart Living concept, European governments have started various initiatives (e.g., the German program SmartLivingNextFootnote 4) that aim to create DEs that can merge the currently fragmented market and its respective actors. Because Smart Living DEs are only starting to form, such ecosystems are in their inception phase. Thus, their main focus is to attract as many actors (on the supply and demand side) as possible. We can use the proposed framework to identify and orchestrate the most promising incentives for attracting and engaging companies and consumers into a Smart Living DE. The first step in applying the framework is identifying incentives for companies and consumers by analyzing their expectations and goals when joining a Smart Living DE.

Identify incentives for companies and consumers

We use the set of company goals and consumer needs provided by the framework to identify incentives for companies and consumers. These need to be first prioritized according to their importance for the consumers and companies’ target groups. In our example, to reduce complexity and showcase the framework’s application, we first seek to find the most important goals of the first and second most important dimensions of the BSC and the top 3 consumer needs, thus incentives. Due to the broad nature of the assessed company goals and consumer needs, such a prioritization of goals is pivotal for applying the framework. The plethora of goals and needs will be challenging to satisfy simultaneously, indicating the suitability of an initial focus on the most critical needs and goals while possibly being broadened over time.

To get a feeling on (i) companies’ rating of the various company goals proposed by the framework, we conducted structured interviews with 27 companies related to the housing or home automation industry. Table 2 indicates the industry of the interviewed companies. Furthermore, we note that 15 interview partners represented large companies, 10 represented SMEs, 1 represented a start-up, and another a public entity related to the housing industry. We constructed the sample to capture a wide variety of companies regarding company size, life cycle, and ownership structure to capture a comprehensive assessment of companies’ goals independent of company types. The interviews were conducted online and lasted 40 min on average. The interview guide comprised the companies’ goals compiled in Fig. 5 (left side). Specifically, the interviewees were asked to rate (1) the importance of the four BSC perspectives (finance, customer, internal process, and learning and growth) and (2) the respective goals by their importance when deciding to participate in a Smart Living DE.

The conducted interviews with companies reveal that when deciding on participation in a Smart Living DE, companies are most interested in the customer perspective, followed by the learning and growth perspective. For instance, the Senior Manager for Strategic Innovation at a home automation company, responsible for strategic partnerships and ecosystems, states, “Yes, I think I would first rank that we already take the customer perspective in the first place, because that should always be the starting point, i.e., also the starting point for action. Learning and growth is then perhaps already two that we also want to grow in the market.” The financial perspective ranks third, revealing a key insight about the Smart Living market: Although customer and growth-related goals might, in the end, also reflect positively in financial key performance indicators, companies seek to participate in a Smart Living DE first and foremost to improve customer- and growth-related goals. In this context, the Managing Director of Technology overseeing the development and production of intercom systems and building communication company explains, “we would like the financial perspective to be at one, but that will then come downstream, and we are working to keep it that way.”

From a customer perspective, companies seek to join the Smart Living ecosystem to improve their value proposition, customer loyalty, or brand reputation. From a learning and growth perspective, the interviewed companies value the new collaboration opportunities such a DE brings. Companies also seek to establish a strong culture of innovation and learn from others to discover their potential for improvement. Table 3 shows the rank of the respective perspectives and the goal importance within those perspectives. Rank 1 shows that the respective goal is, on average, voted to be the most essential and rank 7 the least important when deciding to join a Smart Living DE. Importantly, the ranks do not reflect the topic’s overall importance in other managerial contexts. Case in point, “employee satisfaction” ranks seven, while “collaboration” ranks first within the learning and growth perspective. This indicates that although improving employee satisfaction and new collaboration are essential goals in the overall context of any company, the management does not expect that joining a Smart Living DE will considerably improve its employees’ satisfaction. Instead, it expects that joining a Smart Living DE will enable numerous opportunities for collaborations that otherwise would not have been possible.

To maintain a manageable level of complexity, we will concentrate on the highest-ranked company goals from both the consumers’ and learning and growth perspectives (as highlighted with a grey background in Table 3). From these company goals, corresponding incentives can be derived.

From the consumer perspective, companies seek to improve their value proposition, customer loyalty, and brand reputation. In discussions with domain experts, we determined that matching incentives to address companies’ goal of improving their value proposition within the DE are setting interoperability standards between the components (tools, services, and other products within the DE); defining common data exchange protocols to effortlessly share and evaluate consumer data across different digital touchpoints in the DE; unified user profiles that allow organizations to have a unified view of a customer's interactions across the digital ecosystem can help in tailoring their offerings more effectively; establish a community for open source collaboration, research and development collaborations, and best practice sharing. To address companies’ goal for improved customer loyalty, potential incentives are again data exchange protocols to improve holistic data-driven personalization of products and services; establishing a customer community where they can provide feedback and experiences; ensure interoperability and seamless integration between the products or services from different entities in the ecosystem; promoting a research and development community where shared value propositions are encouraged and materialized jointly; set joint standards for quality assurance and testing, to make sure that the user experience across different products and services are seamless and of high quality. To target companies’ goal to improve their brand image, potential incentives encompass establishing joint Corporate Digital Responsibility standards—i.e., a set of best practices and guidelines about the responsibilities of the organizations when developing digital products and acting in the DE; providing a customer dialogue platform that bundles consumer concerns and feedback; establishing a provider community to share best practices related to brand image, sustainability commitments, and customer education initiatives; providing a conflict resolution mechanism that demonstrates a commitment to fairness and thus can elevate a brand's image; issue transparency reports standards that highlight the brand’s commitments, achievements, challenges, and plans within the ecosystem.

From a learning and growth perspective, companies seek to improve collaborations, establish a culture of innovation, and discover improvement potential. Incentives that could target this company goal encompass establishing a community with shared research and development initiatives, best practices, open innovation challenges, and joint venture initiatives; providing collaborative digital tools between the entities on the supply side of the ecosystem; shared prototyping labs for collaborative idea prototyping and testing; shared knowledge management and learning platforms for idea and value proposition documentation, best practices and prototyping. At this stage, we note that although the listed examples of enabling collaborations might not be exhaustive, they depict stimuli aligned with companies’ goals to achieve collaborations and hone their culture of innovation. For completeness and better understanding, we note that a non-aligned incentive would be one that does not speak to the respective goal of improving collaborations. More specifically, an example of a non-aligned incentive would be establishing a B2C marketplace where users can book smart services the Smart Living DE provides. Because a B2C marketplace serves as a distribution channel for ecosystem services, setting up such a marketplace does not generate better and more diverse collaborations between the companies in the ecosystem, nor does it help to develop companies’ innovation culture.