Abstract

Supporting consumers’ value-in-use (ViU) emergence throughout a usage process has become increasingly challenging as, in today’s environment, usage has shifted from discrete events to continuous e-service interactions. Although researchers acknowledge that ViU is dynamic and evolves over time, most studies treat it as a static concept. Using the empirical context of language learning applications, the authors adopt a dynamic perspective on e-service ViU and extend it with regulatory mode theory using a qualitative approach. By applying the underlying functions of self-regulation: locomotion and assessment, the authors investigate how ViU emerges throughout a usage process and establish an eight-stage ViU emergence process, ranging from initial trigger to termination. By examining a consumer’s usage, assessments, and movements, practitioners can pinpoint a consumer’s location in the ViU emergence process and take appropriate measures to further promote ViU emergence in e-services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As the service economy has continued to grow and digitalization expanded its reach, new electronic services (e-services) are increasingly determining market offers. With the transition of services to the digital world, usage processes have been redefined, fostering more individual use and continuous customer involvement (Williams et al., 2008). For example, the introduction of mobile applications into the field of language learning has enabled the transfer of knowledge through the mobile application interface, allowing learning to take place on demand. However, although knowledge can now be accessed at any time, the user’s continuous active involvement is still indispensable for the learning process.

The gradual shift from discrete usage events to continuous interaction processes in e-services impacts consumer value-in-use (ViU) emergence, as ViU can be linked to not only discrete usage events but also successive usage episodes over the course of a relationship (Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2012). In the context of viewing ViU as a dynamic construct that evolves over time and usage processes as long-term interactions (Beverungen et al., 2017; Grönroos & Voima, 2013), supporting a consumer’s ViU emergence throughout the course of a usage process poses an increasingly difficult management challenge. The emergence of ViU results from the support a service provides—or the lack thereof in achieving the consumer’s goals (Macdonald et al., 2016).

While e-service ViU research confirms that temporal aspects play an important role in ViU emergence (e.g., Heinonen, 2006a, 2007), studies on dynamic ViU emergence thus far are scarce. As Medberg and Grönroos (2020) outline, in spite of the general recognition of ViU as a dynamic construct that evolves over time (e.g., Kleinaltenkamp & Dekanozishvili, 2018; Payne et al., 2008), most studies still treat it as a static concept (e.g., Hartwig & Jacob, 2018; Plewa et al., 2015). Thus, one must look beyond the e-service literature to find studies that investigate dynamic ViU emergence. To date, these approaches have focused on the underlying processes of moments of escapism (Holmqvist et al., 2020), the temporality of ViU creation activities in one-off business-to-business (B2B) service encounters (Razmdoost et al., 2019), and how goal structures evolve in B2B settings (Flint et al., 2002). Despite these advancements, no conceptualization of ViU has evolved that enables the modelling of its dynamic components.

Instead, existing e-service ViU research streams are dedicated to the examination of ViU antecedents (e.g., Bruns & Jacob, 2016; Chen & Dubinsky, 2003; Kleijnen et al., 2007), e-service design (e.g., Blaschke et al., 2019; Schmidt-Rauch & Schwabe, 2014; Sousa et al., 2008), customer participation (e.g., Heinonen, 2006b, 2009; Heinonen & Strandvik, 2009) and e-service ecosystems (e.g., Beverungen et al., 2017; Grieger & Ludwig, 2019; Hein et al., 2019, 2020), and from these streams, several ViU conceptualizations have emerged. In accordance with the e-service literature’s longstanding focus on service quality, e-service ViU is commonly based on a benefit/sacrifice understanding (e.g., Cho & Menor, 2010; Heinonen, 2004, 2006a), which contrasts with Macdonald et al.’s (2016) goal-oriented ViU perspective. By applying the latter perspective instead, we respond to a call for a stronger goal orientation in consumer processes, which can enable more holistic insights on long-term usage processes (Hamilton & Price, 2019).

Since the extant e-service literature falls short of dynamic ViU emergence and less commonly relies on a goal-oriented ViU perspective, previous approaches do not provide a suitable basis for taking a dynamic perspective on goal-oriented ViU emergence; therefore, we extend ViU emergence with a goal-centric theory: regulatory mode theory, which draws on the concepts of locomotion and assessment as underlying functions of self-regulation. Locomotion, hereby, refers to movements or changes in position, which commonly take place toward a desired state or away from an undesired one (Higgins et al., 2003). Assessment, in contrast, depicts a consumer’s evaluation of their goal achievement by comparing their current and desired/undesired end state as well as an evaluation of their means for goal achievement (Kruglanski et al., 2000). Therefore, the concepts of locomotion and assessment are applied to gauge stages and movements within the ViU emergence process along with consumer evaluations. To understand dynamic ViU emergence in e-services by means of regulatory mode theory, we investigate the following research questions: (1) How does locomotion affect dynamic ViU emergence in e-services? and (2) How do assessment processes affect dynamic ViU emergence in e-services?

This paper aims to answer these questions by examining ViU emergence in the course of an e-service usage process. Since this research topic constitutes uncharted territory, we use an explorative research approach herein. We use episodic interviews because they are suitable for reconstructing past episodes in the form of a narration. This technique enables a chronological classification of ViU emergence processes by outlining its locomotion in terms of stages and movements and its assessment processes to further develop prevailing knowledge of the topic (Jovchelovitch & Bauer, 2000).

We conclude that the course of the ViU emergence process is dependent on locomotion (stages & movements) that take place within the process as well as on assessments that go beyond ViU to encompass goals, resources, and usage. Locomotion and assessment can, thereby, occur as different or related functions. We find that the ViU emergence process consists of eight stages, ranging from initial trigger to termination. This examination contributes to existing theory in several ways: (1) by illustrating the dynamic course of the ViU emergence process in terms of an e-service usage process; (2) by outlining how locomotion and ongoing assessments of goals, resources and usage affect dynamic ViU emergence; and (3) by further refining the objects of assessment goals, resources, and usage into subdimensions.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: the next section introduces the underlying streams of ViU emergence in e-services, dynamic ViU emergence, regulatory mode theory as an extension to ViU emergence, and objects of assessment. We then describe our exploratory research approach and methodological choices. After that, we present our empirical findings on goals, resources and usage as objects of assessment and each stage of the ViU emergence process, including movements and assessments. Last, we place our findings within existing theories, which forms the basis of our managerial implications, and we discuss future research opportunities and limitations.

ViU emergence in e-services

Whereas past researchers have used a more traditional conceptualization of value, regardless of the type of output (e.g., value generated for the firm, value generated through an exchange between goods and money; Gummerus, 2013), e-service literature on consumer perceived value revolves predominantly around the concept of ViU. Thereby, these studies focus on ViU emergence through the use of a service and the role of a consumer as its interpreter (e.g., Hartwig & Jacob, 2018; Heinonen, 2006b).

Despite a growing body of e-service ViU research (e.g., Beverungen et al., 2017; Blaschke et al., 2019; Schmidt-Rauch & Schwabe, 2014), disunity prevails on how consumer perceived value is assessed (Gummerus & Pihlström, 2011). Three conceptualizations of value assessments are prevalent in the literature: means–end, phenomenological, and benefit/sacrifices (for overviews, see Gummerus, 2013; Sánchez-Fernández & Iniesta-Bonillo, 2007), of which phenomenological and benefit/sacrifices are particularly prominent in e-service research. A phenomenological conceptualization is typically applied in examinations of ViU co-creation processes (e.g., Grieger & Ludwig, 2019; Hartwig et al., 2021; Helkkula & Kelleher, 2010), in which ViU results from holistic experiences as part of a consumer’s lifeworld (Gummerus, 2013). In contrast, ViU conceptualizations based on a benefit/sacrifice understanding of service quality (e.g., Fan et al., 2020; Heinonen, 2004, 2006a) usually rely on Zeithaml (1988). The consideration of e-service ViU on a benefit/sacrifices basis thereby represents an extension of e-service quality research, which has been widely adopted within the e-service literature (Heinonen, 2006b).

Macdonald et al. (2016) introduced a definition that falls within the phenomenological stream and also incorporates the notion of benefit/sacrifices in a goal-based conception: they establish that ViU emergence takes place through a consumer’s goal achievement during the usage process. They define ViU as “all customer-perceived consequences arising from a solution that facilitate or hinder achievement of the customer’s goal” (p. 98). Therefore, it is less about goods or services themselves and more about the positive consequences they provide for the consumer (Grönroos & Ravald, 2011). Within this scope, the perception of the degree of goal achievement determines ViU emergence and, thus, represents the consumer’s individual assessment process (Eggert et al., 2019). While this conceptualization has already found application in the e-service ViU literature (e.g., Bruns & Jacob, 2014, 2016; Kleinaltenkamp & Dekanozishvili, 2018), it also addresses a call for a stronger goal orientation in consumer processes, through which a more holistic view of long-term usage processes can be generated (Hamilton & Price, 2019). Although research adopting a goal-oriented view of consumer processes is scarce (e.g., Becker et al., 2020; Epp & Price, 2011), this view makes a compelling case for placing a much stronger focus on the purpose a service should ultimately fulfill for consumers (Sawhney, 2006). On these grounds, and because this article aims to examine dynamic ViU emergence through a long-term usage process, we adopt a goal-oriented ViU perspective herein. After establishing a goal-oriented ViU perspective, we continue with an outline of dynamic ViU emergence.

Dynamic ViU emergence

Service scholars commonly acknowledge that ViU is a dynamic and processual construct that evolves over time (Grönroos & Voima, 2013; Heinonen & Strandvik, 2015), a view that a goal-oriented ViU perspective also supports (Macdonald et al., 2016). As Medberg and Grönroos (2020) outline, even though extant research adopts this basic assumption (e.g., Kleinaltenkamp & Dekanozishvili, 2018; Payne et al., 2008), most studies treat ViU as a static concept (e.g., Hartwig & Jacob, 2018; Plewa et al., 2015). E-service ViU research confirms that temporal aspects play an important role in ViU emergence; for instance, studies show that service usage free of time restrictions contributes to ViU emergence in mobile services (Pura & Heinonen, 2008). However, time is understood in terms of freedom of use and not in terms of how ViU evolves over time. In contrast, Holmqvist et al. (2020) combine an examination of luxury experience components with their underlying processes, focusing on moments of escapism in an offline setting. However, while the authors provide insights on underlying processes, they do not address long-term interactions in the context of e-services. Another exception is Razmdoost et al.’s (2019) approach to comprehend the dynamic nature of ViU, which involves examining the temporality of ViU creation activities in one-off B2B service encounters. They show that actors employ two main resource integration processes to manage ViU creation between past, present, and future, such as institutional work and resource reconstruction, thereby emphasizing the role of resources as part of the ViU emergence process over time. A third exception is Flint et al. (2002), who examine changes in the goal structure of B2B customers. More specifically, they assign value changes to different service/product attributes, changing aspired consequences, new goals, or higher performance; however, they do not focus on the process of ViU emergence.

Despite these advancements, no conceptualization of ViU has emerged that enables the modelling of its dynamic components. Therefore, we adopt a goal-centric theory to extend e-service ViU research: regulatory mode theory, which allows us to examine the development of ViU over time in the context of a continuous usage process. As other studies have shown, an extension with self-regulation theories has proven to be a fruitful avenue to investigate goal-oriented usage processes (e.g., Becker et al., 2020). In the following section, we discuss self-regulation, in particular, regulatory mode theory, in more detail.

Regulatory mode theory as an extension to ViU emergence

Self-regulation research is dedicated to the goal achievement process itself, being fundamentally concerned with a comparison between current and desired end states. If an end state is desirable, self-regulation describes the attempt to keep the difference between states to a minimum (approach); however, if a state is undesirable, it refers to the attempt to keep the difference between states to a maximum (avoidance) (Carver & Scheier, 1981, 1990; Higgins, 1998; Higgins et al., 1994).

While various research streams have emerged within this theoretical view, such as implementation models (e.g., Gollwitzer, 1993; Gollwitzer & Moskowitz, 1996; Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006), regulatory fit between goals and goal-striving behavior (e.g., Dweck, 2000; Higgins, 2000, 2005), and achievement motivation models (e.g., McClelland et al., 1953), modern self-regulation theories are dedicated to the goal achievement process. Thereby, these studies go beyond immediate determinants of goal achievement to a process perspective, taking ongoing goal pursuits into account (Brandstätter et al., 2003). One approach that places the goal achievement process center stage is the model of action phases, in which a consumer undergoes four consecutive phases: weighing the pros and cons of options, planning goal implementation behavior, initiating the goal pursuit, and evaluation of progress (Gollwitzer, 1993, 2012; Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987). Another well-respected model, Carver and Scheier’s (1982, 1990) self-regulation model of behavior, uses a repetitive feedback loop to outline the goal achievement process. An individual’s current situation is treated as an input function, which is compared with that individual’s goals, resulting in a confirmation or disconfirmation. If a disconfirmation occurs, the output function—here, the individual’s behavior—is adjusted to reduce this discrepancy. A change in behavior influences the environment, or other influences might do so, leading to changes in the perception of the current situation, which returns to the input function. Carver and Scheier’s model has found application in the investigation of a goal-oriented customer journey: Becker et al. (2020) use this model to gain an understanding of goal-oriented customer journey structures that take place at different levels of goal abstraction, thereby generating insights on how consumers pursue goals and their cognitive and behavioral processes. While applying a self-regulation theory to generate a more profound understanding of a goal-oriented usage process represents a promising avenue, self-regulation goal achievement models aim to illustrate individual behavior in the process of goal achievement. This orientation thus does not account for ViU emergence as a result of goal achievement and, therefore, does not seem appropriate for our purposes. Instead, we apply the underlying functions of self-regulation: locomotion and assessment, which are essential parts of any self-regulating activity.

Commonly, self-regulation models involve some form of movement toward a desired state or away from an undesired state, as captured by the concept of locomotion. At the same time, these models are also concerned with assessment, such as evaluating the gap between a desired state and the current state or assessing the means for goal achievement (Kruglanski et al., 2000). Both locomotion and assessment are found in many models other than the aforementioned (e.g., Carver & Scheier, 1982, 1990; Gollwitzer, 1993, 2012; Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987; Higgins, 1989; Mischel, 1974).

The first means of self-regulation is locomotion, which is commonly defined as “an act or the power of moving from place to place” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). In a self-regulation context, locomotion encompasses all changes in position, regardless of whether these movements lead to a desired end state (Carver & Scheier, 1990; Kuhl, 1985); therefore, it describes any change of position or change of status. Typical movements take place from a current position toward a desired position or away from an undesired position (Higgins et al., 2003). Lewin (1951) notes that these movements might be cognitive and do not have to manifest in overt behavior, though they could translate to actual movement. The second concept, assessment, encompasses an evaluation of the consumer’s current state and desired end state to assess goal achievement (Carver & Scheier, 1990; Kuhl, 1985). This form of self-regulation assessments can be related to ViU assessments as defined by Macdonald et al. (2016), which is based on the extent to which solutions promote the achievement of goals. The terminology refers to the facilitation and hindrance of a consumer’s goal achievement and, therefore, constitutes an evaluation of goal achievement on basis of a solution’s consequences. However, assessment as defined in self-regulation encompasses an evaluation of the discrepancy between the consumer’s current state and desired end state, serving as the basis for goal achievement. In addition, assessment as defined in self-regulation can also encompass additional evaluation processes, which can consist of separate evaluations of current or desired end states as well as progress toward or the means with which to achieve a goal (Higgins et al., 2003). These assessment forms thereby represent an extension to the applied perspective of ViU, which is exclusively focused on the promotion of a consumer’s goal achievement via service solutions. In contrast to classical self-regulation theory, regulatory mode theory regards assessment and locomotion as different functions, so locomotion and assessment might occur together, separately, or to varying degrees (Higgins et al., 2003; Kruglanski et al., 2000).

Because existing ViU research has not gone beyond recognizing dynamic ViU emergence, we adopt locomotion and assessment as underlying concepts of self-regulation. Building on this foundation, we apply the conceptualizations of locomotion and assessment to the context of e-service ViU to examine dynamic ViU emergence. We apply locomotion to identify distinct ViU stages and how they are arranged through movements. We then use assessment to outline consumer evaluations of predefined objects and how they affect the dynamic ViU emergence process. With this approach, we aim to extend the prevailing understanding of the ViU emergence process by providing a dynamic perspective on ViU in e-services and thereby fill the existing research gap. Before we delve into the method section, we first outline relevant objects of assessment found in the ViU literature.

Objects of assessment

ViU scholars have long recognized that studies on subjective ViU assessments are essential for management practice and science (Heinonen et al., 2010; Macdonald et al., 2011), yet assessment processes beyond ViU have received limited attention so far. However, ViU theory provides hints on several classes of assessment objects. While goals in a first place provide the reference for ViU, they may also change over time and, thus, become the object of assessment. As Macdonald et al., (2011, p. 679) put it: “Customers’ goals change at different stages of the relationship and affect their evaluations of value.” At the same time, ViU research continuously stresses the role of resources for the emergence of ViU (Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2012; Vargo & Lusch, 2004). Hartwig and Jacob (2018), for example, show in a mobile application context that resource restrictions affect ViU emergence negatively. Hence, customers will make the resources disposable to them the object of assessment during use processes. Finally, overt usage of a service marks another object of assessment ViU researchers draw on. Ravald (2010, p. 48), for example states, that “value does not emerge only in use and possession as such; rather it emerges in activities rendered possible.” Heinonen (2009) applied this logic to the context of e-services and confirmed its validity. Summarizing, goals, resources, and usage come forth as potential objects of assessment in regard of ViU, each of which will be explained in more detail next.

Goals are defined as desired end states that guide behaviors in an effort to achieve or avoid them (Austin & Vancouver, 1996; Carver & Scheier, 1981). Consumers form goal hierarchies that map higher-order and subordinate goals. They might be interdependent; for instance, the desire to work or study abroad as a higher-order goal is related to the subordinate goal of learning the corresponding language (Peterman, 1997). Woodruff (1997) also introduces this hierarchy of goals in a ViU context, outlining goals at increasingly higher abstraction levels, from product attributes, to product consequences, to goals/purposes. Goals/purposes are then considered the desired end states. With the pursuit of multiple simultaneous goals, consumers set priorities with regard to their dependencies and feasibility (Huffman et al., 2000). Research indicates that goals are diverse in nature, such that goals for the usage of a service may differ, which in turn influences the consumer’s ViU assessments (Macdonald et al., 2011, 2016). Goal determination is considered a dynamic process; thus, goals are prone to constant adaptations (Carver & Scheier, 1981). In accordance with earlier work, we adopt an intentional view of goals; in our research context, the decision to learn a language through a mobile application is a conscious one, such that goals are willingly determined (Huffman et al., 2000).

The second object of assessment, resources, assumes a central role in the ViU emergence process as the means for ViU emergence or as a ViU proposition (Arnould et al., 2006; Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2012). In this context, resources do not represent a benefit in themselves but rather serve as a basis for ViU emergence if utilized in accordance with a consumer’s needs. They are versatile and can be defined as “those that require some action to be performed on them to have value (e.g. natural resources) and … those that can be used to act (e.g. human skills and knowledge)” (Vargo & Lusch, 2011, p. 184). In e-service literature, a dependency between ViU and a resource’s scope and variety is evident; thereby, varying resource configurations can impact a consumer’s ViU assessments differently (Gummerus, 2010). Furthermore, Hartwig and Jacob (2018) show in a mobile application context that resource restrictions affect ViU emergence negatively—for instance, when resource consumption exceeds the capacity of the resource. In general, technology plays an important role in resource integration, as it facilitates the transmission of resources between consumers and providers (Spohrer & Maglio, 2008). Continuing with the example of language learning applications, language proficiency is transmitted via the mobile application. The exchange of language proficiency requires the consumer’s active involvement through the usage of the language learning application to reach their goal, such as to speak a language fluently or to expand their vocabulary.

Another key aspect in ViU emergence is use of the service (Vargo & Lusch, ). As Woodruff and Gardial (1996) put it, a service’s value to the customer can only be assessed by understanding its potential uses. The customer therefore plays a decisive role in the ViU emergence process, as the service is only of value to them if they include it in their ViU emerging activities (Ravald, 2010). These activities involve designing own usage behaviors as part of integrative and collaborative processes oriented toward their life and preferences (Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2012; Vargo & Lusch, 2004). These co-creating activities can take on various forms, such as emotional engagement through marketing efforts, self-service activities, service experiences, process self-selection, and product co-design (Payne et al., 2008, p. 84). Therefore, service providers are dependent on customers, as they are indispensable for the provision of services (Gummesson, 1998). While general service studies do address how customers can participate in a service, the role of intensity of use is more pronounced in e-service ViU research because it is a prerequisite for e-service provision (Heinonen, 2009). In this context, research shows that ViU assessments are more favorable when usage is of higher intensity given the service usage was considered successful. (An example of an unsuccessful service encounter is the active search for specific information on a website that is not found [Heinonen, 2006a].) With the rise of service technology, a change in usage behavior has become apparent, moving from discrete usage episodes toward continuous interaction processes (Beverungen et al., 2017). This is supported by recent findings that connect ViU emergence to not only independent events but also successive episodes in the course of a relationship (Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2012). Emerging ViU thereby impacts future consumer behavior and practices (Ford, 2011; Lemke et al., 2011), which highlights once more the need for a dynamic perspective on ViU emergence.

Methodology

Research design

Because developing a ViU emergence process extended by regulatory mode theory constitutes uncharted territory, we use an explorative research approach. To this end, we follow a qualitative research strategy, which allows an in-depth investigation of the participant’s perspective. Moreover, it enables the investigation of temporal and structural specificities in our research context (Toulmin, 1990). By conducting empirical research on the dynamic emergence of ViU in an e-service context, we further refine ViU theory and answer Brodie and Löbler’s (2018) call for more midrange theory that bridges ViU research with empirical evidence.

To select a suitable research context, we followed preceding ViU studies’ choice criteria (e.g., Bruns & Jacob, 2014; Hartwig & Jacob, 2018). First, to illustrate dynamic ViU emergence in e-services, we needed a service offer with a strong goal orientation, so that it is in line with the goal-oriented perspective of ViU. Second, we needed a lengthy service process because it is considered the middle ground between individual service encounters and whole customer relationships, which allows for a detailed and dynamic evaluation of ViU (Medberg & Grönroos, 2020). In addition, we needed a usage process that requires the consumer’s active participation and is individually configurable, so that the research context encourages individual ViU emergence and represents a modern service offer.

These criteria led us to choose language learning applications as a suitable research context. Learning languages is a lengthy process that requires an active involvement of the consumer’s knowledge and skills to reach goal achievement. Mobile applications offer a digital platform to transfer this type of knowledge and educational content and have, thus, increased its accessibility. Therefore, consumers are in a position to design their usage process more freely, so that it is in line with their daily life, plans, and goals. Moreover, the use of mobile services is nowadays deeply embedded in the consumers’ daily lives (Gummerus & Pihlström, 2011), and the use of applications for educational purposes is increasingly well-established, as they rank among the most popular app categories (42matters, 2020).

Sample selection

We deployed a purposive sampling strategy, which is commonly used in qualitative studies and enables the selection of information-rich cases. To this end, we chose respondents who had prior experience with language learning applications to help us understand the key aspects under study based on their experience. To ensure a wide range of cases, we selected participants with diverse motivations (e.g., professional reasons, stays abroad, emigration plans), goals (from the acquisition of basic language skills to fluent conversation skills), and experience (ranging from under one year to more than five years) (Marshall, 1996; Patton, 2002). Interviewees were recruited via open invitations published as paper posters in universities and other educational institutions. Out of 16 responses, we excluded 3 due to an inability to schedule interviews or unclear motivation of participation. Table 1 provides demographic details of interview participants. Our total sample size of 13 (11 male and 2 female respondents) is in line with generally accepted standards, considering the point of theoretical saturation usually occurs between 9 and 12 interviews (Guest et al., 2006).

Data collection

The 13 episodic interviews took place in Germany within a period of three months. In the interest of understanding the process of dynamic ViU emergence, we opted for a data collection method that enables us to reconstruct the consumer’s usage process, beginning with the decisive moment that initiated the usage process and continuing to current use or until its termination. Therefore, we chose to use a form of narrative interviewing, which enabled us to more directly reconstruct social events from interview participants (Jovchelovitch & Bauer, 2000, p. 59). More specifically, we chose episodic interviews, as they allow a primary focus on concrete consumer episodes/experiences and permit questioning during the narrative process to obtain further background information. The narrative character of the interview allowed interviewees to guide us through their entire usage process of language learning applications. We were able to obtain a chronological arrangement of each usage process, which served as a basis for the identification of distinct VIU emergence stages, movements, and underlying assessments (Bates, 2004; Flick, 1997; Jovchelovitch & Bauer, 2000).

We followed the seven-step episodic interview process:

-

1.

We introduced the interview principle to participants.

-

2.

We asked them an introductory question regarding their understanding of language learning applications, and we asked them to reconstruct their entrance to the study field by describing the moment the decision to learn a language was triggered.

-

3.

We asked participants to describe each episode of the goal achievement process chronologically up to the present use or the end of the goal achievement process. If participants had gone through several goal achievement processes (e.g., learning several languages), we considered each process separately. To obtain more detail, we asked questions about the backgrounds of the respective situations to fathom movement and assessments. As the participants guided us through the whole process, the meaning of the topic for daily life became clear in each episode.

-

4.

We reviewed central aspects of the issue (e.g., the assessment processes regarding goal achievement and other forms of assessments, movements within the usage process, and how these aspects are related).

-

5.

We asked questions regarding expected changes and future plans regarding their goal achievement process.

-

6.

We asked about aspects that had not yet been addressed during the interview.

-

7.

We documented the interview (Flick, 1997).

We pretested the interview guide, which resulted in some adjustments to the interview structure and wording. We conducted the interviews either in person or by telephone, and they lasted on average 48 min. Participation in the interview was voluntary, and confidentiality was assured. Every interview was recorded and subsequently transcribed to facilitate further analysis.

Data analysis

Due to the narrative character of the interview, we decided to use a structuralist analysis to ensure a rigorous methodical approach.

This method differentiates between a syntagmatic dimension and a paradigmatic dimension (Jovchelovitch & Bauer, 2000). On the syntagmatic dimension, the researcher lists all components of each participant’s narrative in their sequential order. The purpose of the paradigmatic dimension is to aggregate those components according to their specific content into a single or in several category schemes. For the episodes and the movements, this aggregation procedure was open and entirely explorative. For assessment objects, our analysis was theory-driven, and we matched identified content with the categories of goals, resources, and usage intensity derived from ViU research.

The base logic of our structure is exemplified in Table 2, where we demonstrate our procedure by listing sample statements from three respondents covering the first three stages of the ViU emergence process. It also illustrates how we utilized these respondents’ answers to identify categories.

We carried out the coding procedure in MAXQDA, which entailed coding over 1,000 text passages. The coding process method involved several steps. First, we broke down each usage process into its episodes to identify their typical characteristics from a consumer’s perspective, constituting the first part of locomotion. This phase aimed to reveal what characterizes each ViU stage and distinguishes it from the others. We coded these characteristics according to the participants’ wording and then summarized them to form more abstract stage descriptions. Second, we chronologically arranged the individual episodes for each ViU emergence process to outline movements as proposed in regulatory mode theory. To this end, we examined all identified processes with regard to their sequence and aggregated them to obtain a universal ViU emergence process (for a detailed overview of each interview participant’s individual ViU emergence process, see Online Appendix 1). In the third step, we examined nonchronological elements encompassing predefined objects and their assessment processes. This step was theory-driven: first, we matched objects of assessment (goals, resources, and usage) with existing ViU theory, and second, we examined assessments as proposed in ViU research and regulatory mode theory. We studied all objects of assessment with regard to their components, which resulted in a finer segregation. Then, we assigned all objects to the identified stages of the ViU emergence process and analyzed their respective assessment. Finally, we examined how the assessment of ViU as well as goals, resources, and usage is related to the movement within the ViU emergence process from one stage to another, connecting locomotion and assessment.

Findings

Building on literature, we examined three objects of assessment that influence the emergence of ViU and refined them into several subdimensions during the course of the analysis: goals (prioritization and aspirations), resources (selection and suitability), and usage (intensity) (see Table 3). We also identified the following eight stages of the ViU emergence process through the data analysis: initial trigger, goal determination, subscription, orientation, initial euphoria, routine, decline, and termination. (See Sect. 4.2 for a description of each ViU stage and the corresponding assessment processes and locomotion, as well as an illustration of the ViU emergence process.)

In this section, we first present our empirical results on goals, resources, and usage as objects of assessment within the ViU emergence process. Subsequently, we outline our findings regarding the ViU emergence process by describing each ViU stage, the objects of assessment at play, and, finally, movements within the course of the ViU emergence process (for a detailed overview of sample quotes, see Online Appendix 2).

Objects of assessment

Goals

The first object of assessment, goals, consists of two underlying dimensions: prioritization and aspirations. Consumers typically pursue several goals simultaneously. For instance, subordinate goals (e.g., passing a language exam) need to be fulfilled to reach a higher-order goal (e.g., being accepted at a university). Thus, a prioritization takes place determining how actively a goal is pursued compared with others. One participant described the dependency of higher-order and subordinate goals and its change in priorities within the ViU emergence process as follows: “That's why I thought: as ambitious as I am and as much as I enjoy it [the language], it does not correspond to my own goals.”(I13).

The second dimension, goal aspirations, encompasses consumers’ desired level of goal achievement. Although these aspirations may be more or less clearly defined before the usage process starts, they can take different forms, ranging from stability to adaptation. Adaptations can entail reducing, increasing, or eliminating language learning aspirations. For instance, one participant described an increase in goal aspirations in the following way: “I think it then developed in[to] this bigger project; I’m now making sure I’m doing it every day.”(I5) As these adaptions take place along the ViU emergence process, consumers might use an e-service offer to fulfil changing goal aspirations.

Resources

The second object of assessment, resources, consists of selection and suitability. The selection of resources takes place when the consumer compares various language learning offers, such as mobile applications, courses, or books. Common reasons for adopting an online language learning application are the languages that are offered, cost, availability, the low inhibition threshold, familiarity of previous use, or flexibility as outlined by one interviewee: “You don't have to book a course, and you don't only get to do it next Wednesday, but you can do it now, at noon, in the evening, on the train, at work.” (I12) These reasons for adoption may occur in any variation. The aspired-to goal must be achievable with the offer in order to match demand and supply.

In the course of the ViU emergence process, an ongoing evaluation of the language learning application’s suitability for goal achievement takes place. This evaluation can relate to the resource’s suitability for overall goal achievement or for the acquisition of specific skills. Resource suitability can thereby be based on the structure, the transparency, or the learning content (in terms of comprehensibility and depth) of the language learning application. For instance, users viewed language learning applications as more suitable to provide an entry point to the language than the expansion of already advanced knowledge. Consequently, resource suitability might evolve during the usage process, influencing ViU emergence. The interviews made apparent that many participants also adopted a multimethod approach using several language learning resources at a time, each of which fulfilled different purposes as exemplified by participant I8’s comment: “I like this multimethod approach because I feel that it makes total sense to me that I try to cover the different aspects of a language.”

Usage

The last object of assessment is usage, which encompasses usage intensity and refers to the frequency and duration of usage. Along the ViU emergence process, clear time frames become apparent based on the usage intensity, which can range from very intense usage to none at all. Whereas the excitement of the new can lead to a high intensity level (e.g., if the language learning application is used for the first time), increasing experience often decreases usage intensity and thereby provides an indication of which ViU emergence stage the consumer is in. Furthermore, participants described an overall reduction of usage when they realized they had set unrealistic daily or weekly goals; for example: “At some point, I realized that I was overwhelmed by the quantity [learning volume per day] and that it was unrealistic for me, so I didn't even start.” (I8).

The ViU emergence process

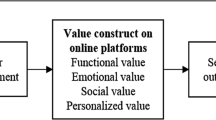

In this section, we present ViU stages as we identified them from our interviews with their respective assessments and movements (see Table 4). Figure 1 graphically illustrates the process.

Initial trigger

Stage description

At the beginning of each ViU emergence process is the initial trigger. This stage represents the reason a consumer strives toward a certain goal. Interview participants referred to specific situations or arising circumstances that either reinitiated or triggered the desire to learn a language. In the context of language learning applications, an initial trigger might involve social motives, such as romantic attachments or foreign family members. Participants also mentioned cultural motives (e.g., the desire to develop a cultural understanding or connect with locals) and professional reasons (e.g., communication with local contract partners, pupils, consultation seekers). Other interviewees mentioned specific situations or upcoming events as other triggering situations (e.g., holidays, stays abroad). If a usage process is triggered by any kind of event or happening, living through the event—and, thus, the initial trigger—represents a natural end to the ViU emergence process. As participant I1 described, his usage was directed toward a moment: “A stay abroad in Slovakia was imminent.”

Assessment and movement

The initial trigger represents a decisive situation or circumstances, which leads to an assessment of existing goal priorities as part of a self-regulation process. Therefore, the prioritization of existing goals might be diminished, even though the new goal is not yet clearly defined. The initial trigger must be sufficiently pronounced so that the consumer is motivated to move to the next stage of goal determination. For instance, one interviewee outlined that his inability to participate in a French conversation among his friends was the triggering situation that led to goal determination: “My feeling was, okay, I can't even join in a conversation in Paris, because I can’t say a sentence.” (I7).

Goal determination

Stage description

The second stage of the ViU emergence process, goal determination, provides the benchmark for ViU emergence as the aspired-to level of goal achievement is defined. Goals for language learning applications range from language proficiency to goals that require language competency, such as receiving a residence or work permit through language learning. For the latter, language proficiency is a necessary subordinate goal that must be fulfilled to reach the higher-order goal. Whether language proficiency is viewed as a subordinate or higher-order goal, it manifests in the form of the level of proficiency a participant wants to reach or specific competences and skills that a participant wants to acquire/keep. Participant I5, for instance, expressed his goal in terms of specific skills: “Being able to have a simple conversation even; that was kind of my goal.” Generally speaking, there are no limitations on what goals are pursued and which aspirations are pursued within these goals. Therefore, goals should be considered in their specific context, and consumers more or less consciously determine these goals.

Assessment and movement

In goal determination, the client assesses how advanced their language skills should or must be if a higher-order goal is pursued. This assessment takes place considering the goal’s feasibility as well as with regard to the consumer’s desire to obtain specific abilities. If they have already used a language learning service offer, they may judge it suitable for their aspired-to goal. In this case, goal aspiration assessment is typically accompanied by a reassessment of earlier goal aspirations, which are respectively adjusted. Once a consumer’s goal aspirations are more or less defined, the further course of the ViU emergence process is determined. This movement is dependent on whether the resource is assessed as suitable. If consumers do not have previous experience with suitable resources, movement toward subscription takes place. However, as one participant outlined, once a consumer has already gained experience with potential e-service offers and considers one of them suitable for the intended goal, a movement to the subsequent stage of initial euphoria (described in Sect. 4.2.5) may take place when initiating the usage process: “I take the Russian language course via XYZ, because I knew that it actually worked pretty well with Spanish.” (I13).

Subscription

Stage description

After a consumer determines a goal, they next specify the means of goal achievement. Within this specification process, consumers compare various language learning offers. Interview participants reported that they first did some internet research, asked for recommendations within their social environment, or had specific applications in mind from previous advertising exposure. The actual comparison process of language learning offers can involve the languages offered, especially when less-common languages are pursued. Other aspects mentioned pertained to the mobile application design and pricing. Therefore, an evaluation of the service offer occurs in accordance with its apparent suitability for goal achievement, as one interviewee described as follows: “From then on, I only checked which one met my requirements best, and that’s when I decided to choose brand XYZ.” (I3) Taking into account previously defined consumer goals, it becomes evident that consumers may adopt a single usage process for a wide range of goal aspirations. When the consumer makes a positive decision to use the application, the point at which the user enters an official commitment with the provider takes place. With regard to usage-based offerings, this process entails the consumer’s registration to a service, herein referred to as subscription.

Assessment and movement

In the subscription stage, resource selection takes place as the consumer assesses potential language learning offers that may go beyond mobile applications and entail other means. The consumer directly compares offerings with regard to their range, service design, and price, and this assessment serves in this stage as a basis for the registration decision. After the selection of a service offer, Interviewee I12 described the movement from subscription to orientation and thus the entering of the usage stage as follows: “And with one click you have the language.”

Orientation

Stage description

As soon as the consumer subscribes to the service, the orientation stage begins. This stage typically does not last long; the consumer browses through the applications’ main functions to get an overview of its usability and its operating principles, as participant I7 describes: “I first looked at what languages there are, I found that very interesting, and I got a little lost there.” Other terms participants used to describe their usage behavior in this stage were “playing around,” “testing,” and “trying it out.” However, they also noted that a full impression typically does not occur until a later stage, after they had familiarized themselves with the mobile application through repeated use. This orientation process is transferable to other e-service offers that require consumers’ active involvement.

Assessment and movement

Once the orientation stage starts, the consumer assesses the resource suitability of the offering. In the context of language learning applications, this assessment is mainly rather superficial, as consumers interact for the first time with the language learning application. Therefore, the assessment refers mainly to the applications’ overall offer, layout, and usability. One participant described this process as follows: “I wanted to try out if this is a pleasant way to learn for me.” (I3) The assessment within this phase represents an important threshold for subsequent usage: if the resource is considered suitable to support ViU emergence, the usage stage of initial euphoria begins. If the resource is, however, assessed as unsuitable, movement toward termination takes place.

Initial euphoria

Stage description

The initial euphoria stage is exciting, fun-filled, and highly involving for language learning application users, as exemplified by interviewee I1: “I just wanted to keep going, the next exercise, keep trying, keep testing.” This stage has the most intensive usage, as consumers long to complete one language learning unit after another, feeling an urge to keep going. This phase evokes more playful e-service contexts. At this point, consumers are highly motivated to achieve their goal and enjoy the novelty of the situation. Progress toward goal achievement is, thereby, marked by many small milestones, which foster intensified usage.

Assessment and movement

The ViU assessment in initial euphoria is initially guided by the milestones the language learning application provides by moving from one level to the next. However, as the initial euphoria stage proceeds, the consumer makes a more profound assessment of their progress toward goal achievement—for example, on the basis of their ability to retain previously learned course content. The very intense usage of the language learning application in this stage often exceeds a consumer’s expectations and is, therefore, positively assessed. However, this positive evaluation is often replaced by a more negative evaluation as soon as they reduce usage intensity and move toward the routine stage, described by one participant as follows: “At some point, the initial enthusiasm is gone, and you got used to the program and to the process, and then the normality crept in and then it wasn’t so exciting anymore.” (I2).

Routine

Stage description

When the initial euphoria of using the service offer declines, the routine stage starts. This transition is evident when usage of the language learning application declines in duration and frequency. In this stage, the consumer is familiar with the mobile application and its functionalities and demonstrates repeated usage behaviors. It is within these routinized behaviors that individual language learning rhythms and habits are developed within everyday life. For instance, participants stated that they established one or two fixed times per week when they studied or that usage had become an integral part of their commute. These routines can also be applied to the learning process itself, as in participant I5’s case: "I realized that the app only works if you keep repeating it, and it’s not a magic button that will give you the language and you just press it. You have to be more active, and I realized how to make it work for me.” Compared with the previous phase, the enthusiasm for the new is no longer present, and consumer focus lies mainly on building a routine.

Assessment and movement

In the routine phase, several forms of assessment take place. First, consumers assess the usage regularity and duration of the language learning application by their adherence to usage routines. Second, they assess the resource suitability on a more profound level than in previous stages; the suitability assessment concerns whether the learning content is clearly structured, whether consumers have an overview of the course program, how comprehensible the explanation of learning content is, and whether the depth of knowledge is sufficient. These aspects determine whether the resource supports consumers in gaining new knowledge, as well as the extent to which already acquired knowledge is still available, representing progress toward goal achievement. Various movements might take effect from the routine stage onward, depending on assessment processes. For example, if another trigger occurs that engenders new goal aspirations, movement to a new ViU emergence process takes place. If goal priorities are evaluated and subsequently reduced, movement toward the decline stage takes place that is accompanied by a reduction in usage intensity. Alternatively, movement may take place directly to termination; one participant noted this takes place if a resource is not considered suitable for goal achievement anymore: “That's why I stopped using it [application]. In my opinion, it wasn't systematic.” (I6).

Decline

Stage description

The decline phase is characterized by a low intensity of use. The consumer still uses the application occasionally but no longer adheres to the developed learning rhythms. Participants referred to “sporadic or less usage,” “not as intense [usage],” “less regularity,” or, as participant I13 describes it: “Then it happened that it died down so badly that I hardly used it anymore.” This can be caused by a focus shift toward other goals, which pushes ViU emergence regarding language learning in the background. Therefore, only little progress is made toward goal achievement, resulting in little potential for ViU emergence.

Assessment and movement

An assessment of the usage intensity shows only limited potential for ViU emergence. This decrease might be due to a reassessment of the priority of learning a language. Alternatively, the language learning application may be assessed as unsuitable for goal achievement at this point, which may be because the learning content is not transparent, it is no longer challenging enough, or it does not sufficiently cover advanced language levels. From this stage onward, two movements can be made. If the initial goal level of language proficiency is still aspired to at this point and goal priority reduced on a temporary basis, a back-movement to routine can occur through an increase in usage intensity. However, if the assessment results in goal aspirations being lowered and goal priorities reduced in favor of others, a movement toward termination is likely. For instance, Interviewee I1 described the decrease in goal aspirations as follows: “The goal of learning Spanish has also become a little less, shifted a bit into the background.”

Termination

Stage description

When usage has stopped completely, the consumer enters the termination stage. This stage might take on different forms. First, the initial trigger may no longer be relevant because it has already occurred (e.g., holiday, stay abroad, event) or because social motives are no longer present (e.g., romantic relationships or friendships did not last). Second, the consumer may have reached his or her goal (e.g., the desired skills or level of language proficiency) and therefore terminates usage. Third, the consumer may not have reached the goal but decided to no longer pursue it via the language learning application. Last, a natural end may be introduced to the usage process as described by one participant, who completed all available course content of the language learning application successfully: “Well, I got to the end of Spanish, so I finished all units [of the language learning application].” (I13).

Assessment and movement

In termination stage, the consumer no longer uses the application or deletes it, either having achieved or having not achieved their goals or no longer having the same goals. Alternatively, the consumer assesses that the resource is unsuitable (e.g., insufficient coverage of the topic, or accompanying of advanced language levels), they have completed the entire course content, or the initial trigger is no longer present. In any case, an assessment of goal priorities might take place, leading to a reprioritization of goals. If ViU emerged, consumers move to a new ViU emergence process, which begins with a new trigger. If ViU emergence did not take place, but aspirations toward the initial goal still exist, the consumer might select another resource in the stage of subscription. One interviewee described the termination of the language learning application for another resource as follows: “But then the language course replaced the app completely and then I didn't use the app anymore.” (I12).

Contributions

Theoretical contributions

This study expands the current state of research on dynamic ViU emergence, which is generally recognized but rarely investigated (Medberg & Grönroos, 2020). In particular, this study outlines the course of dynamic ViU emergence via an eight-stage circular model, the ViU emergence process. In deviation from previous models, which prescribe a fixed sequence of consumer processes, the ViU emergence process depicts a nondeterministic approach, thereby reflecting the dynamic character of ViU, which is in line with Day (1999, p. 70), who advocates a self-reinforcing “value-cycles” perspective rather than linear chains. From a service process perspective, it also evokes Pentland’s (2003) view, which shows that the personalization of service processes leads to sequential variety.

We further conclude that the course of the ViU emergence process is dependent on movements that take place along the ViU emergence process as well as on assessment processes that go beyond ViU to encompass goals, resources, and usage intensity. In so doing, we highlight the important role of assessments and movements as underlying concepts of self-regulation for shaping the process while also demonstrating that goals, resources and usage are continuously assessed throughout the ViU emergence process. The ongoing assessment denotes a dynamic perspective of ViU in contrast to previous static one-off evaluations or earlier value conceptualizations, such as value generated through an exchange between goods and money (Gummerus, 2013).

Furthermore, the application of regulatory mode theory as an extension to ViU emergence represents uncharted territory, which, to the best of our knowledge, no extant studies have yet entered. As Becker et al. (2020) have shown, the adoption of a self-regulation theory is a promising approach for goal-oriented consumer processes. Unlike them, we have applied the underlying concepts of self-regulation—locomotion and assessment—instead of a self-regulatory model. In accordance with regulatory mode theory, locomotion can be dependent on, but also independent of, assessments (Higgins et al., 2003). As our results show, assessments are drivers of movement unless there is only one subsequent stage, in which case pre-stage assessments are not decisive. By examining a consumer’s usage intensity, assessments, and movements, practitioners can pinpoint where a consumer is located within the ViU emergence process, so that appropriate measures can be taken to further promote consumers’ ViU emergence.

The applied goal-oriented view also contributes to existing e-service ViU research, which has so far examined ViU on basis of service quality dimensions advocating a ViU measurement of benefit and sacrifices (e.g., Heinonen & Strandvik, 2009; Heinonen, 2004, 2006a). Our study proposes a different origin for e-service ViU emergence, which goes beyond the consideration of service quality dimensions. Whereas current conceptualizations of ViU assessments from a goal achievement perspective have presumed an active shaping of ViU, our work identifies an emergent component to ViU, which, to date, is only found in studies adopting a benefit/sacrifice ViU assessment understanding (Heinonen & Strandvik, 2009). We, therefore, support Heinonen and Strandvik’s (2009) proposed shift in terminology toward the term “ViU emergence” and away from “ViU creation,” which presupposes an active shaping of ViU (Vargo & Lusch, 2004, 2008).

Lastly, our investigation of goals, resources, and usage as main objects of assessment—contributes further to the ViU literature by identifying and examining their sub-dimensions. While each of the examined objects is well recognized within the literature (e.g., Hartwig & Jacob, 2021; Kleinaltenkamp & Dekanozishvili, 2018), previous approaches tended towards an examination on a more generic level, thus not taking into account its respective subdimensions. Unlike them, we have developed a more refined elaboration of each object, which allows us to identify five underlying dimensions: goal prioritization and goal aspirations (goals), resource selection and resource suitability (resources), and usage intensity (usage); each of which is able to affect the further course of dynamic ViU emergence.

Managerial implications

Our findings propose a shift in managerial thinking from consumer experience thinking toward consumer ViU emergence thinking. Instead of focusing on how consumers can be engaged in co-creating activities with the firm, service providers should focus on becoming involved in consumers’ lives (Heinonen et al., 2010).

E-service providers should adopt a goal-oriented perspective when devising long-term usage processes, as doing so can highlight opportunities to support a consumer’s ViU emergence. Special emphasis should be placed on the alignment between consumer goals, the service offer, and consumer usage. To this end, e-service providers should tailor the service offering toward a consumer’s aspired-to goal level or skills by allowing them to specify these aspects when engaging in the e-service. This way, service elements can be composed such that they are aligned with these specifications, ensuring the service offers suitability on a long-term basis.

In addition to aligning the service offering with consumer goals, providers should devise e-services in a way that facilitates their usability, setup, quality, and enjoyment. For example, e-services should be easily navigable, and a clear overview of the service offering should be given. Moreover, content should be complete, accurate, and comprehensible. Last, enjoyment during usage can be further enhanced by visual appeal or game design elements. E-service providers should also promote individual usage behavior and the formation of usage routines through a flexible e-service implementation. One way to do so is by giving consumers milestones or the opportunity to set their own. In either case, providers should support consumers in specifying realistic goals, as unattainable milestones can impede the goal achievement progress. Another way to do so is to enable consumer activity planning, which simplifies the scheduling of activities within the consumer’s life. Last, the introduction of value-auditing processes is advisable for e-service providers, as they can help consumers visualize ViU through performance-based feedback (Macdonald et al., 2016).

Along the usage process, e-service providers should take various measures to further promote ViU emergence. Marketing efforts regarding consumer acquisition should be directed toward a consumer’s goal achievement and acknowledge various goal aspirations. Furthermore, the range of services should be clearly presented with a focus on differentiating service offerings. Once consumers are registered, e-service providers should ensure that consumers are guided and accompanied through their initial and subsequent usage process. This guidance should make evident how the product or service supports the user’s goal aspirations. To ensure long-lasting and intensive usage, the consumer should have access to a diversified service offer accompanied by value-auditing processes and milestones. When irregularity of consumer activities becomes apparent, e-service providers should take countermeasures to make users aware of their initially aspired-to goal and encourage them toward goal achievement. When the e-service has been terminated, it is advisable to find out why a service or product is no longer used. Consumers who achieved their goal can be used as advocates, and alternative services can be positioned. If a consumer did not achieve their goal, e-service providers should use their feedback for further service or product enhancements that could potentially reduce the churn rate. Overall, consumer activities, assessments, and movements provide e-service providers with an indication of a consumer’s ViU emergence, which can be used as a basis to develop appropriate measures.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

The present study provides a more elaborate understanding of the dynamic ViU emergence process in e-services than previous research. Unfortunately, we had to limit ourselves to a single case study, although we still strived toward a generalization of the results. We acknowledge the possibility that generalization may need to be investigated—for instance, on the basis of future research examining other usage processes in various service and product contexts. Therefore, we do not rule out the possibility that stages such as initial euphoria may differ in certain service contexts. For example, in our research context, this stage is associated with fun and the novelty of the situation, which might not occur in less playful service contexts. Subsequent quantitative studies would also be beneficial to allow a statistical generalization. While this study examines ViU emergence along one usage process, it is certainly desirable to look at dynamic ViU emergence across multiple interrelated usage processes. Future research projects should therefore include various resources available to a user. Furthermore, this study relies on narrative accounts, which allows the reconstruction of past episodes. A longitudinal study involving multiple measurement points would be a fruitful avenue to gain even deeper insights of ViU emergence over time. In this vein, the individual phases of the model can also be used as objects of future research to gain a better understanding of them. In addition, our investigation focused on the ViU emergence process from a consumer perspective. For future studies, it is worth considering how ViU emerges from a provider perspective and how consumer and provider perspectives can be contrasted.

Data availability

Yes, audio files and transcripts.

Code availability

Yes, MAXQDA.

Change history

15 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

References

Arnould, E. J., Price, L. L., & Malshe, A. (2006). Toward a cultural resource-based theory of the customer. In R. F. Lusch & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The service-dominant logic of marketing: dialog, debate and directions (pp. 91–104). M. E. Sharpe.

Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120(3), 338–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.3.338

Bates, J. A. (2004). Use of narrative interviewing in everyday information behavior research. Library & Information Science Research, 26(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2003.11.003

Becker, L., Jaakkola, E., & Halinen, A. (2020). Toward a goal-oriented view of customer journeys. Journal of Service Management, 31(4), 767–790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-11-2019-0329

Beverungen, D., Müller, O., Matzner, M., Mendling, J., & Vom Brocke, J. (2017). Conceptualizing smart service systems. Electronic Markets, 29(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-017-0270-5

Blaschke, M., Riss, U., Haki, K., & Aier, S. (2019). Design principles for digital value co-creation networks: A service-dominant logic perspective. Electronic Markets, 29(3), 443–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00356-9

Brandstätter, V., Heimbeck, D., Malzacher, J., & Frese, M. (2003). Goals need implementation intentions: The model of action phases tested in the applied setting of continuing education. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320344000011

Brodie, R., & Löbler, H. (2018). Advancing knowledge about service-dominant logic: the role of midrange theory. In S. L. Vargo & R. F. Lusch (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of service-dominant logic (pp. 565–577). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Bruns, K., & Jacob, F. (2014). Value-in-use and mobile technologies. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 6(6), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-014-0349-x

Bruns, K., & Jacob, F. (2016). Value-in-use: antecedents, dimensions, and consequences. Marketing: ZFP–Journal of Research and Management, 38(3), 135–149.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1981). Attention and self-regulation: A control-theory approach to human behavior. Springer-Verlag.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1982). Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 92(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.92.1.111

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1990). Principles of self-regulation: Action and emotion. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior (Vol. 2, pp. 3–52). Guilford Press.

Chen, Z., & Dubinsky, A. J. (2003). A conceptual model of perceived customer value in e-commerce: A preliminary investigation. Psychology & Marketing, 20(4), 323–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10076

Cho, Y. K., & Menor, L. J. (2010). Toward a provider-based view on the design and delivery of quality e-service encounters. Journal of Service Research, 13(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670509350490

Day, G. S. (1999). The market driven organization: Understanding, attracting, and keeping valuable customers. Simon and Schuster.

Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press.

Eggert, A., Kleinaltenkamp, M., & Kashyap, V. (2019). Mapping value in business markets: An integrative framework. Industrial Marketing Management, 79, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.03.004

Epp, A. M., & Price, L. L. (2011). Designing solutions around customer network identity goals. Journal of Marketing, 75(2), 36–54. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.75.2.36

Fan, D. X., Hsu, C. H., & Lin, B. (2020). Tourists’ experiential value co-creation through online social contacts: Customer-dominant logic perspective. Journal of Business Research, 108, 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.008

Flick, U. (1997). The episodic interview: Small scale narratives as approach to relevant experiences. LSE Methodology Institute Discussion Papers-Qualitative Series 5.

Flint, D. J., Woodruff, R. B., & Gardial, S. F. (2002). Exploring the phenomenon of customers’ desired value change in a business-to-business context. Journal of Marketing, 66(4), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.66.4.102.18517

Ford, D. (2011). IMP and service-dominant logic: Divergence, convergence and development. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.06.035

42matters (2020, August 18). Google Play statistics and trends 2020. https://42matters.com/google-play-statistics-and-trends.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: The role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 141–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000059

Gollwitzer, P. M. (2012). Mindset theory of action phases. In P. van Lange (Ed.), Theories of social psychology (pp. 526–545). SAGE Publishing.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Moskowitz, G. B. (1996). Goal effects on action and cognition. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 361–399). Guilford Press.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

Grieger, M., & Ludwig, A. (2019). On the move towards customer-centric business models in the automotive industry: A conceptual reference framework of shared automotive service systems. Electronic Markets, 29(3), 473–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-018-0321-6

Grönroos, C., & Ravald, A. (2011). Service as business logic: Implications for value creation and marketing. Journal of Service Management, 22(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231111106893

Grönroos, C., & Voima, P. (2013). Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0308-3

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Gummerus, J. (2010). E-services as resources in customer value creation: A service logic approach. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(5), 425–439. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521011073722

Gummerus, J. (2013). Value creation processes and value outcomes in marketing theory: Strangers or siblings? Marketing Theory, 13(1), 19–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593112467267

Gummerus, J., & Pihlström, M. (2011). Context and mobile services’ value-in-use. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(6), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2011.07.002

Gummesson, E. (1998). Implementation requires a relationship marketing paradigm. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(3), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070398263006

Hamilton, R., & Price, L. L. (2019). Consumer journeys: Developing consumer-based strategy. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47, 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00636-y

Hartwig, K. L., & Jacob, F. (2018). How individuals assess value-in-use: theoretical discussion and empirical investigation. Marketing: ZFP–Journal of Research and Management, 40(3), 43–62.

Hartwig, K., & Jacob, F. (2021). Capturing marketing practices for harnessing value-in-use. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2021.1895671

Hartwig, K., von Saldern, L., & Jacob, F. (2021). The journey from goods-dominant logic to service-dominant logic: A case study with a global technology manufacturer. Industrial Marketing Management, 95, 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.04.006

Heckhausen, H., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motivation and Emotion, 11(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992338

Hein, A., Schreieck, M., Riasanow, T., Setzke, D. S., Wiesche, M., Böhm, M., & Krcmar, H. (2020). Digital platform ecosystems. Electronic Markets, 30(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00377-4

Hein, A., Weking, J., Schreieck, M., Wiesche, M., Böhm, M., & Krcmar, H. (2019). Value co-creation practices in business-to-business platform ecosystems. Electronic Markets, 29(3), 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00337-y

Heinonen, K. (2004). Reconceptualizing customer perceived value: The value of time and place. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 14(2/3), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520410528626

Heinonen, K. (2006a). Temporal and spatial e-service value. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 17(4), 380–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230610680677

Heinonen, K. (2006b). The role of customer participation in creating e-service value. In: M. Maula, M. Hannula, M. Seppä, & J. Tommila (Eds.), Frontiers of E-business research, B3.

Heinonen, K. (2007). Conceptualising online banking service value. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 12(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fsm.4760056

Heinonen, K. (2009). The influence of customer activity on e-service value-in-use. International Journal of Electronic Business, 7(2), 190–214. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEB.2009.024627

Heinonen, K., & Strandvik, T. (2009). Monitoring value-in-use of e-service. Journal of Service Management, 20(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230910936841

Heinonen, K., & Strandvik, T. (2015). Customer-dominant logic: Foundations and implications. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(6/7), 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-02-2015-0096

Heinonen, K., Strandvik, T., Mickelsson, K. J., Edvardsson, B., Sundström, E., & Andersson, P. (2010). A customer-dominant logic of service. Journal of Service Management, 21(4), 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231011066088

Helkkula, A., & Kelleher, C. (2010). Circularity of customer service experience and customer perceived value. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 9(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1362/147539210X497611

Higgins, E. T. (1989). Knowledge accessibility and activation: Subjectivity and suffering from unconscious sources. In J. S. Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought (pp. 75–115). Guilford Press.

Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60381-0

Higgins, E. T. (2000). Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist, 55(11), 1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.11.1217

Higgins, E. T. (2005). Value from regulatory fit. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(4), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00366.x