Abstract

Fractional flow reserve (FFR) measured during invasive coronary angiography is an independent prognosticator in patients with coronary artery disease and the gold standard for decision making in coronary revascularization. The integration of computational fluid dynamics and quantitative anatomic and physiologic modeling now enables simulation of patient-specific hemodynamic parameters including blood velocity, pressure, pressure gradients, and FFR from standard acquired coronary computed tomography (CT) datasets. In this review article, we describe the potential impact on clinical practice and the science behind noninvasive coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography derived fractional flow reserve (FFRCT) as well as future applications of this technology in treatment planning and quantifying forces on atherosclerotic plaques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) is well established as the noninvasive standard for anatomic assessment of coronary artery disease (CAD) [1, 2]. With improvements in spatial and temporal resolution, both mechanical and software-based, as well as implementation of large detector scanners the field of coronary CTA has seen progressive improvements over the last 10 years [3–5]. In addition to image quality improvements, multiple scanner advances in both image acquisition and reconstruction have enabled coronary CTA to be performed consistently with radiation dose exposure in the 1–5 mSv range [6–8]. Despite the rapid technology progression, resting coronary CTA remains a strictly anatomic test and, as such, similar to conventional invasive angiography (ICA), it lacks the necessary data to guide revascularization decision making, which mandates objective evidence of ischemia [9, 10]. Accordingly, the recent “Outcomes of Anatomic vs Functional testing for Coronary Artery Disease” (PROMISE) trial, compared coronary CTA with frontline noninvasive ischemia testing and demonstrated an almost 50 % increase in downstream referrals to ICA and a doubling in coronary revascularization rate which, however, did not translate into improved outcomes [11••]. These findings emphasize the need of accurate noninvasive gatekeeping to the catheterization laboratory beyond anatomic assessment. The latter gap in noninvasive diagnostic testing may be addressed through a strategy combining anatomic and functional data [12]. The introduction of pharmacologic stress CT perfusion has resulted in significant interest with strong early results compared with both noninvasive and invasive measures of ischemia [4, 13]. Although a promising technique, CT perfusion requires the administration of a pharmacologic stress agent and a repeat CT acquisition, thereby increasing both the time required and the radiation exposure to the patient. Furthermore, CT perfusion provides data analogous to coronary flow reserve, which has known limitations in isolating epicardial coronary disease that is treatable with revascularization from microvascular disease without any established therapy. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) as measured during ICA is broadly recognized as the gold standard for the discrimination of lesion-specific ischemia. FFR, which assesses the ratio of flow across a stenosis to putative flow in the absence of stenosis, is strongly associated to the clinical outcome in a continuous manner [14••]. Moreover, FFR has been shown in multiple randomized trials to guide revascularization in a cost-effective manner compared with both angiographic-guided revascularization and medical therapy [15–17]. Although a robust tool for the adjudication of the hemodynamic significance of a stenosis, FFR is limited by its invasiveness and cost, and hence in real-world practice it is used for coronary revascularization decision-making in a minority of patients [18, 19]. With recent technological and scientific advancements, noninvasive methods to calculate FFR have been developed. The integration of computational fluid dynamics and quantitative anatomic and physiologic modeling now enables simulation of patient-specific hemodynamic parameters including blood velocity, pressure, pressure gradients, and FFR from standard acquired coronary CT datasets [20••]. We herein describe the science behind, clinical evidence supporting, and future applications related to coronary CTA derived FFR (FFRCT).

Coronary CT Angiography Derived FFR (FFRCT)

Science and Diagnostic Performance

FFR can be derived from coronary CTA image data acquired using standard acquisition protocols without the need for additional imaging, medication, or radiation. FFRCT analysis uses mathematical models of blood flow derived from patient-specific data extracted from coronary CTA images and solved on high-performance computers. Any mathematical model of blood flow in the circulation includes at least 3 elements: first, a description of the anatomic region of interest; second, the mathematical “governing equations” enumerating the physical laws of blood flow within the region of interest; and third, “boundary conditions” to define physiologic relationships between variables at the boundaries of the region of interest [21]. Although the anatomic region of interest and the boundary conditions are unique to each patient and the specific vascular territory, the governing equations describing velocity and pressure are universal and apply in different patients and other arterial beds. The extraction of the patient-specific anatomic model from image data is performed using image processing algorithms [22, 23]. The basic physiologic principles behind FFRCT have previously been described in detail [20••]. The first principle is that the total coronary blood flow (which is proportional to the myocardial oxygen demand) at rest can be quantified from the myocardial mass as assessed by CT. The second principle is that the microcirculatory vascular resistance at rest is inversely proportional to the size of the coronary arteries supplying the myocardium, and thus the caliber of both healthy and diseased vessels adapt to the amount of flow they carry. The third principle states that the vasodilatory response of the coronary microcirculation to adenosine infusion is predictable, allowing computational modeling of the maximal hyperemic state. Integration of these patient-specific mathematical models of coronary physiology to 3D computational fluid models enable computation of coronary flow and pressure at each point in the coronary tree under hyperemic conditions. Finally, FFRCT is calculated from the ratio of coronary pressure to aortic pressure under simulated maximal hyperemic conditions.

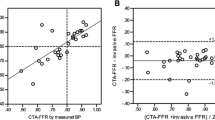

The diagnostic performance of FFRCT in patients with or suspected stable CAD has been tested in 3 prospective multicenter trials, the “Diagnosis of Ischemia-Causing Coronary Stenoses by Noninvasive Fractional Flow Reserve Computed from Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiograms” (DISCOVER-FLOW) study [24] the “Determination of Fractional Flow Reserve by Anatomic Computed Tomographic Angiography” (DeFACTO) study [25••], and the “Analysis of Coronary Blood Flow Using CT Angiography, Next Steps” (NXT) [26••] study, respectively. A total of 609 patients and 1050 vessels have been investigated. An overview of study design, populations, and estimates of FFRCT diagnostic performance in these 3 trials is presented in Table 1. In all 3 trials, FFRCT revealed high per-patient and per-vessel discrimination for the presence of ischemia with blinded comparison to measured FFR. Moreover, the diagnostic performance of FFRCT was consistently superior compared with anatomic interpretation alone. However, in the DeFACTO trial, the prespecified end-point was not met as the FFRCT accuracy lower limit of the 95 % confidence interval (67 %–78 %) did not exceed 70 % [25••]. Moreover, although superior to coronary CTA, the diagnostic specificity of FFRCT in the DeFACTO study was rather low (42 % for coronary CTA vs 54 % for FFRCT). However, FFRCT demonstrated higher per-patient and per-vessel discrimination of ischemia compared with coronary CTA alone with AUC’s of 0.81 vs 0.68 (P < 0.001) and 0.81 vs 0.75 (P < 0.001), respectively [25••]. Of note, the DeFACTO study was conducted with an early generation FFRCT analysis algorithm, and use of pre-acquisition beta-blockers and nitroglycerin was not mandated. Thus, in 25 % of the vessels assessed, nitroglycerin was not administered, which may have resulted in underestimation of the coronary artery diameter with a resultant increase in false positive FFRCT [27•]. Moreover, beta-blockers were not used in almost one-third of patients, potentially adversely affecting CT image quality and increasing discordance between FFRCT and FFR [27•, 28]. The most recent and largest study, the NXT trial incorporated learnings from the previous 2 trials, including use of the latest generation of FFRCT analysis software [26••, 29]. In the NXT trial, the per-patient diagnostic accuracy of FFRCT in predicting lesion-specific ischemia was superior to anatomic assessment by coronary CTA, 81 % vs 53 % (P < 0.001) arising from an increase in specificity from 34 % to 79 % (P < 0.001). Notably, the NXT trial cohort pre-test probability of significant CAD was in the intermediate range, thus representing patients in whom noninvasive imaging is recommended [30]. The improved diagnostic performance of FFRCT in the NXT trial compared with the DeFACTO trial reflects substantial refinements in FFRCT technology and physiologic modeling, as well as increased focus on coronary CTA image quality, in particular, regarding heart rate control and the use of nitroglycerin [27•, 29]. Accordingly, preliminary data indicate that employing the “NXT” FFRCT computation technology and standardized CT image metrics on the DeFACTO CT data set, results in comparable diagnostic performance of FFRCT as in the NXT trial [31]. In the NXT trial, there was a good direct correlation of FFRCT to invasively measured FFR (r = 0.82), with a slight underestimation of FFRCT (mean difference, 0.03) compared with FFR. The reproducibility of repeated FFRCT calculations are high with a coefficient of variation between 1.4 % and 4.6 % [32]. Patient examples illustrating the clinical utility of FFRCT in patients with coronary lesions with or without ischemia is shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Case example 1. A 66-year-old man was referred for evaluation of atypical chest pain. a, Coronary CTA showed extensive coronary calcification (Agatston score = 1509) and significant coronary artery stenosis could not be excluded in either of the major coronary arteries. b, FFRCT was 0.64, 0.70, and 0.74 in the left anterior descending (LAD), the circumflex (Cx), and the right (RCA) coronary arteries, respectively. c, Invasive coronary angiography showed stenoses (arrows) in the mid-LAD, Cx, and the RCA, with measured FFR in LAD and Cx being 0,62 and 0.61, respectively. FFR interrogation in RCA was not technically possible. The patient was treated successfully with coronary artery bypass grafting. FFRCT = coronary computed tomography angiography derived fractional flow reserve

Case example 2. A 67-year-old female was referred for evaluation of atypical chest pain. a, Coronary CTA showed minimal coronary calcification (Agatston score = 8) and a 60 % coronary artery stenosis in the right coronary artery (RCA) (arrow). b, FFRCT distally in the RCA was 0.91. c, Invasive coronary angiography showed a 60 % stenosis in the RCA (arrow) with measured FFR distally of 0.93. The patient was treated successfully with medication. FFRCT = coronary computed tomography angiography derived fractional flow reserve

FFRCT Diagnostic Performance in Specific Subpopulations

FFRCT has high diagnostic performance in the presence of coronary calcification (Fig. 1) [33]. In a NXT trial substudy including 214 patients (333 vessels), there was no difference in diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, or specificity of FFRCT across Agatston score quartiles, including the highest quartile of patients with Agatston scores ranging between 416 and 3599 [33]. In vessels with the highest Agatston scores, FFRCT showed significant improved discrimination of ischemia compared with coronary CTA alone (0.91 vs 0.71, P = 0.004), corresponding to 60 % correct reclassification of cases when moving from coronary CTA to FFRCT. The apparent robustness of FFRCT in the event of coronary calcification is most likely a result of the FFRCT computation process, including information on the global coronary and myocardial anatomy [33]. In contrast, coronary CTA stenosis assessment relies on identification of segmental changes with resultant reduction in lumen interpretability and, for this reason, the presence of artifacts may have a greater impact on interpretation.

In a recent substudy from the NXT trial of vessels with serial multiple lesions (n = 18), FFRCT values were co-registered with measured FFR across the lesions, and trans-lesional differences between FFRCT and FFR were compared [34]. The mean values of the most distal FFR and FFRCT in the same regions were 0.72 ± 0.10 and 0.69 ± 0.11, wheeas FFR and FFRCT were ≤0.80 in 13 and 14 vessels, respectively. The coefficient of correlation between trans-lesional delta FFR and FFRCT in each segment was excellent (0.92, P < 0.001).

The diagnostic performance of FFRCT has been studied only in patients suspected of stable CAD, and thus the generalizability of FFRCT to other patient categories is currently unknown. These patients include those with left ventricular hypertrophy, diabetes, previous myocardial infarction, or patients with coronary stents or by-pass grafts.

Comparison to Conventional Ischemia Testing Modalities

Current guidelines recommend noninvasive functional imaging testing (eg, stress echocardiography, single photon emission computed tomography, or cardiac magnetic resonance) as the first line diagnostic strategy in patients suspected of CAD [30]. In meta-analyses, using ICA stenosis severity as the reference standard, noninvasive functional testing has shown high diagnostic performance for detection or exclusion of obstructive CAD [30]. However, when these diagnostic tests are evaluated using measured FFR rather than ICA stenosis as the reference standard, diagnostic performance diminishes [35]. Most published studies utilizing FFR as the reference standard were small and single center-based, and in many of these studies FFR was often not measured in all vessels, with FFR values assigned to vessels (and vascular perfusion territories) on the basis of the angiographic findings in a significant proportion of patients (vessels) [35]. This strategy may lead to misadjudication since patients with stenosis severity >50 % or even >70 % often have FFR values >0.80 [9, 10, 36–38], whereas patients with <50 % stenosis may have FFR values ≤ 0.80 [36–39]. Hitherto no studies have compared head-to-head the diagnostic performance of conventional noninvasive functional testing modalities vs FFRCT using FFR as the reference standard.

Clinical Utility, Cost Effectiveness, and Quality of Life

In the context of rising global healthcare costs, greater attention is focused on cost-effectiveness of procedures. The field of noninvasive diagnostic testing comprises a bewildering array of test choices often resulting in 2 separate tests for assessment of coronary anatomy and ischemia [30]. Despite the extensive use of noninvasive testing, ICA continues to play a major role in the assessment of patients suspected of CAD. As a result of inaccurate diagnostic discrimination associated with the use of current noninvasive testing modalities, 60 % or more of patients referred for ICA on a suspicion of CAD do not have obstructive disease [40], and the majority of patients having revascularization performed do not have evidence of ischemia [41]. Moreover, patients with a positive ischemia testing result are only slightly more likely to have obstructive CAD at ICA than those who do not undergo testing [42].

Resource utilization and clinical outcome related to the clinical use of FFRCT in symptomatic patients with suspected CAD have been evaluated in the prospective, multicenter “Prospective Longitudinal Trial of FFRCT: Outcome and Resource impacts” (PLATFORM) trial [43••]. This study examined the clinical effectiveness impact of a strategy using FFRCT to guide management compared with the usual testing strategy in 11 European centers. A total of 584 patients (mean age 61 years, 40 % women) with new-onset chest pain, no prior history of CAD, and an intermediate pre-test likelihood of obstructive CAD were enrolled. Patients referred for noninvasive testing were enrolled in a separate stratum than patients referred for invasive testing. Each stratum was further subdivided into usual care or FFRCT-guided care. The primary endpoint was the rate of finding no obstructive stenosis among those with planned ICA, as defined by ≥50 % in any coronary artery by quantitative coronary angiography (QCA, core laboratory measurement) or invasive FFR < 0.80. Secondary endpoints included clinical outcomes, downstream testing and treatment, resource utilization, and quality of life measures [43••]. Study results showed high rates of finding no obstructive CAD by ICA in both the planned noninvasive and planned ICA groups. In the planned ICA group, 73 % of usual care patients had no obstructive CAD compared with only 12 % of patients guided by FFRCT, an 83 % reduction (P < 0.0001). Although clinicians in the PLATFORM study were not protocol-driven to utilize FFRCT test results, in 61 % of patients with planned ICA, the angiogram was cancelled after receiving FFRCT results. Nonetheless, there was no difference in coronary revascularization rates (32 % in usual care and 29 % in FFRCT, P = ns) and there was a 90 % increase in the number of patients with both functional and anatomic information prior to revascularization. Among patients intended for noninvasive testing, there was no difference in the rate of finding no obstructive CAD at ICA between usual care (6 %) and FFRCT (13 %, P = 0.95). There were no adverse clinical events among patients in whom ICA was cancelled on the basis of FFRCT, and there was no difference in clinical outcome between the usual care and FFRCT-guided groups at 90 days. The latter findings are in accordance with a recent single-center real-world study comprising 185 consecutive patients with stable CAD and intermediate range coronary lesions showing a favorable 12-month follow-up clinical outcome in patients with FFRCT > 0.80 (69 % of the study cohort) being deferred from ICA [44•].

Simulation analyses based on historic data indicate that FFRCT guidance for selection of ICA and decision-making on coronary revascularization may reduce costs in stable CAD [45, 46]. The effects of using FFRCT instead of usual care on costs and quality of life (QOL) in the PLATFORM study have been recently published [47••]. Total medical costs were derived from the number of diagnostic tests, invasive procedures, hospitalizations, and medications during 90-day follow-up multiplied by summed US cost weights. Changes in QOL were assessed using the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, the EuroQOL, and a visual analog scale. Among patients with planned ICA, mean costs were 32 % lower among the FFRCT group than among the usual care group ($7343 vs $10,734, P < 0.0001). Among patients with planned noninvasive testing, mean costs were not significantly different between the FFRCT group and the usual care group ($2679 vs $2137, P = 0.26). Each of the QOL scores improved in the overall study population (P < 0.0001). At 90 days, in the planned noninvasive testing stratum, QOL scores were significantly higher in FFRCT patients than in usual care patients, whereas in the planned ICA stratum the improvements in QOL were similar in the FFRCT and usual care patients.

FFRCT Testing and Interpretation in Clinical Practice

No current guidelines provide recommendations about the clinical use of FFRCT testing and its interpretation. As the first line cohort, we recommend FFRCT testing to be applied in patients with intermediate range lesions in whom coronary CTA interpretation is most challenging [9], and where guidelines recommend additional ischemia testing to be performed [30]. This is in accord with previous trial evidence showing high and superior diagnostic performance of FFRCT compared with stenosis assessment by coronary CTA in intermediate lesions [24, 25••, 26••, 48]. It is well known that a coronary stenosis with FFR ≤ 0.75 in general causes ischemia, whereas stenoses with FFR > 0.80 are almost never associated with exercise induced ischemia [49]. Accordingly, an FFR interpretation “grey-zone” ranging between 0.75 and 0.80 has been introduced in which measures other than FFR are recommended to be taken into account for decision making on revascularization [49]. Previous studies assessing the diagnostic performance of FFRCT used a binary outcome based on a threshold of 0.80 [24, 25••, 26••]. However, as for FFR, a “black and white” decision-making based on a specific FFRCT threshold may not always fit into the reality of clinical practice. Accordingly, in the most recent NXT trial, despite diagnostic superiority compared with coronary CTA stenosis assessment alone, the FFRCT per-patient specificity and positive predictive value in predicting ischemia was modest (79 % and 65 %, respectively), and thus a substantial rate of false-positive results remained [26••]. In line with these findings, the aforementioned real-world study showed that only 55 % of lesions with FFRCT ranging between 0.75 and 0.80 caused ischemia using FFR (threshold, 0.80) as the reference standard, whereas ischemia was documented in 92 % of lesions when FFRCT was ≤0.75 [44•]. On the other hand, prognosis was favorable in patients being deferred from ICA on the basis of a normal FFRCT result [44•]. Based on our current knowledge regarding FFRCT diagnostic performance, and the fact that the overall prognosis in contemporary practice of stable CAD is favorable [11••, 43••, 44•], we recommend in patients (vessels) with FFRCT > 0.80 or ≤0.75 a dichotomous interpretation strategy, whereas in patients with FFRCT ranging between 0.75 and 0.80, decisions on referral to ICA (and decision-making on coronary revascularization) should be based on all available information, in particular regarding severity of angina, which is the main target of PCI (Table 2). The clinical value and safety of this FFRCT interpretation approach needs delineation in future studies.

Limitations of FFRCT Testing

Although no special imaging protocols are required for FFRCT assessment, significant CT imaging artifacts such as motion, low contrast, or blooming from coronary calcification may impair the diagnostic performance of coronary CTA and thus of FFRCT. In the DeFACTO and NXT trials, 11 % and 13 % of the patients had nonevaluable coronary CTA images [25••, 26••]. In contrast, in the aforementioned real-world report of consecutive patients having FFRCT performed, only 2 % of the patients failed to meet the image quality requirements for FFRCT analysis, and in the total cohort comprising more than 1200 patients referred for coronary CTA, a conclusive CT-based anatomic or anatomic-physiological result was available in >90 % [44•]. Issues of CT uninterpretability can be minimized by adhering to coronary CTA image acquisition guidelines, particularly by administration of heart-rate lowering medication and sublingual nitrates before image acquisition [27•, 28, 44•, 50]. Although it has been shown that FFRCT seems to provide significant diagnostic improvement compared with coronary CTA even at lower levels of coronary CTA image quality [51], noncompliance with societal guidelines on best coronary CTA acquisition practice [50] is associated with impaired FFRCT diagnostic performance [27•]. In the DeFACTO trial, administration of a pre-scan beta-blocker increased FFRCT diagnostic specificity from 51 % to 66 % (P = 0.03), whereas nitroglycerin pretreatment within 30 minutes of CT was associated with improved specificity from 54 % to 75 % (P = 0.01).

Currently, FFRCT testing requires offsite computer processing requiring 2–6 hours. However, significantly faster FFRCT-testing processing times resulting from software improvements are expected in the near future. Concerns on the perceived loss of control of local assessment and the current processing time associated with FFRCT testing have driven renewed interest in past generations of reduced order computational fluid modeling versions that are less computationally intense and when coupled with less comprehensive anatomic modeling enables on-site analysis with reduced analysis times, but an unknown impact on diagnostic performance. Thus, while noninvasive on-site and fast (<1 hour) CT-derived FFR has shown interesting results in small, single-center, retrospective studies [52, 53], further investigations in prospective multicenter trials are needed in order to determine the actual diagnostic performance of this technique [54]. The relative long-term prognosis and cost-efficiency of FFRCT testing compared with conventional ischemia testing modalities is not known, but studies are ongoing. In the Computed TomogRaphic Evaluation of Atherosclerotic Determinants of Myocardial IsChEmia (CREDENCE) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:NCT02173275), which is a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional study of patients scheduled to undergo clinically indicated nonemergent ICA, the diagnostic performance of FFRCT vs myocardial imaging perfusion assessment (SPECT, positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance myocardial imaging) is compared using FFR as the reference standard.

Future Applications of Coronary CTA Derived Computational Fluid Dynamic Modeling

Predicting Outcomes of Cardiovascular Interventions

A particular strength of the computational methods used to derive FFRCT lies in the possibility of altering the patient anatomic or physiological model to predict the anticipated benefit of treatments. The potential use of this technology for planning PCI procedures was explored in a pilot study including 44 patients who had coronary CT and FFRCT before catheterization and measured FFR before and after PCI [55]. FFRCT was performed in a blinded fashion prior to and after virtual stenting of the lesions treated invasively. The diagnostic accuracy of FFRCT to predict ischemia (FFR ≤ 0.8) after stenting was 96 %. Further developments in predicting the potential benefit of alternate revascularization strategies are on the horizon.

Quantifying Biomechanical Forces Acting on Blood Vessels

There are a variety of different biomechanical forces that act on blood vessels arising from internal pressure and flow and external tissue support. These applied forces result in stress acting on the surface or within blood vessels, where stress is defined as force per unit area. In addition to external applied forces, blood vessels have intrinsic, or residual, stresses emanating from growth and remodeling [56]. These residual stresses are present even in the absence of external applied forces. An example of a residual stress manifests when a vessel is transected and retracts or shortens due to the longitudinal tension in the vessel wall. A detailed discussion of all of the intrinsic and extrinsic forces and stresses in blood vessels is beyond the scope of this review, and herein we focus on forces resulting from internal flow and pressure acting on blood vessels and atherosclerotic plaques. Wall shear stress (WSS) is defined as the tangential force per unit area acting on the luminal surface. Axial plaque stress (APS) is defined as the axial component of the hemodynamic stress acting on stenotic lesions [57•]. APS and WSS both result from hemodynamic forces acting on the luminal surface, but have important differences. APS is strongly related to the absolute pressure on the surface of the plaque, whereas WSS is independent of the absolute pressure but closely coupled to flow and the pressure-gradient. APS is much larger than WSS (ie, approximately 40 times larger than the maximum WSS even in tight stenoses and under hyperemic conditions where WSS is maximal [57•]). Both WSS and APS can be derived from the velocity and pressure fields calculated by patient-specific modeling of coronary blood flow derived from CT data. Image-based computational methods have been used to compute wall shear stress noninvasively in the human abdominal aorta [58, 59], the extracranial and intracranial cerebral arteries [60–63], and the pulmonary arteries [64, 65].

Plaque Initiation and Progression

WSS plays a role in maintaining endothelial function and is likely to influence plaque initiation and progression [66–69]. WSS is the product of the blood viscosity and the gradient of the velocity field at the luminal surface. WSS is sensed by the endothelium and in turn influences normal endothelial function, as well as atherosclerosis localization and progression. Image-based modeling techniques have also been used to evaluate wall shear stress in the human coronary arteries based on invasive data [70–74], and to a lesser extent using noninvasive data [75, 76]. The future application of image-based modeling derived from CT data holds great promise for understanding the relationship between WSS and CAD.

Plaque Evolution, Destabilization, and Rupture

Whereas the mechanical influence of WSS is confined to a narrow zone of the vessel wall near the endothelium, APS acts throughout the entire thickness of the plaque and, as such, is likely to play a more direct role in plaque rupture. In a recent publication, Choi et al. described the potential role of APS in plaque rupture and its relationship with lesion geometry [57•]. APS was found to uniquely characterize the stenotic segment and differentiate forces acting on upstream and downstream segments of a plaque. While WSS and pressure were consistently higher in upstream than in downstream segments, APS could be higher at the downstream than upstream segment in some lesions, thus potentially explaining why some plaques rupture at the downstream segments. Figure 3 depicts the FFRCT result and the APS for a patient experiencing a cardiac arrest, and primary percutaneous coronary intervention of an occluded left anterior descending artery lesion occurring 1 year after a coronary CTA examination. Although coronary CTA identified a stenotic lesion, a rubidium-82 rest-stress perfusion study was deemed normal and the patient was treated medically [77]. The FFRCT and APS analyses were performed retrospectively (but without any knowledge of the patient history) based on the coronary CTA data acquired 1 year prior to the myocardial infarction, indicating a very low FFRCT result and high APS on the segment upstream of the minimum lumen area [57•]. The utility of FFRCT and axial plaque stress for predicting plaque rupture are currently being evaluated in the “Exploring the Mechanism of the Plaque Rupture in Acute Myocardial Infarction” (EMERALD) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT02374775).

Case example 3. FFRCT and APS analysis computed under simulated hyperemic conditions performed retrospectively on coronary CTA data acquired one year prior to a subsequent cardiac arrest and revascularization of a left anterior descending artery (LAD) lesion. a, FFRCT analysis indicates a markedly functionally significant lesion in the mid-LAD, b, coronary CTA images reveal a mixed non-calcified and calcified plaque, c, APS values are elevated in the upstream segment of the lesion, d, APS averaged over the upstream segment is in the upper range of values reported by Choi et al. [57•]. Note that APS is approximately 50 times higher than WSS. APS = axial plaque stress; FFRCT = coronary computed tomography angiography derived fractional flow reserve; MLA = minimum lumen area; WSS = wall shear stress

Conclusions

FFRCT is a novel noninvasive method that uses computational fluid dynamics for calculation of FFR by using patient-specific modeling derived from standard acquired coronary CTA datasets. During the last 5 years, FFRCT has undergone remarkable advancements in technology, and its support in the clinical community challenging conventional coronary CTA and ischemia testing. Moreover, the clinical potential of combining computational fluid dynamics with CT to derive informantion that may enable prediction of the outcomes of coronary interventions or assessment of plaque vulnerability is emerging.

Abbreviations

- APS:

-

Axial plaque stress

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography angiography

- CTP:

-

Computed tomography perfusion

- FFR:

-

Fractional flow reserve

- FFRCT :

-

Fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography

- ICA:

-

Invasive coronary angiography

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- WSS:

-

Wall shear stress

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Abdulla J, Abildstrom SZ, Gotzsche O, Christensen E, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C. 64-multislice detector computed tomography coronary angiography as potential alternative to conventional coronary angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:3042–50.

Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1724–32.

Heydari B, Leipsic J, Mancini GB, Min JK, Labounty T, Taylor C, et al. Diagnostic performance of high-definition coronary computed tomography angiography performed with multiple radiation dose reduction strategies. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:606–12.

Rochitte CE, George RT, Chen MY, Arbab-Zadeh A, Dewey M, Miller JM, et al. Computed tomography angiography and perfusion to assess coronary artery stenosis causing perfusion defects by single photon emission computed tomography: the CORE320 study. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1120–30.

Ropers U, Ropers D, Pflederer T, Anders K, Kuettner A, Stilianakis NI, et al. Influence of heart rate on the diagnostic accuracy of dual-source computed tomography coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2393–8.

Achenbach S, Marwan M, Ropers D, Schepis T, Pflederer T, Anders K, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography with a consistent dose below 1 mSv using prospectively electrocardiogram-triggered high-pitch spiral acquisition. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:340–6.

LaBounty TM, Leipsic J, Poulter R, Wood D, Johnson M, Srichai MB, et al. Coronary CT angiography of patients with a normal body mass index using 80 kVp versus 100 kVp: a prospective, multicenter, multivendor randomized trial. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W860–7.

Leipsic J, Nguyen G, Brown J, Sin D, Mayo JR. A prospective evaluation of dose reduction and image quality in chest CT using adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:1095–9.

Meijboom WB, Van Mieghem CA, van Pelt N, Weustink A, Pugliese F, Mollet NR, et al. Comprehensive assessment of coronary artery stenoses: computed tomography coronary angiography versus conventional coronary angiography and correlation with fractional flow reserve in patients with stable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:636–43.

Tonino PA, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, Oldroyd KG, Leesar MA, Ver Lee PN, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2816–21.

Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, Mark DB, Al-Khalidi HR, Cavanaugh B, et al. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. New Engl J Med. 2015;372:1291–300. The first large-scale randomized trial comparing clinical outcomes following coronary CTA vs conventional ischemia testing in stable coronary artery disease.

Patel MR. Detecting obstructive coronary disease with CT angiography and noninvasive fractional flow reserve. JAMA. 2012;308:1269–70.

Ko BS, Cameron JD, Meredith IT, Leung M, Antonis PR, Nasis A, et al. Computed tomography stress myocardial perfusion imaging in patients considered for revascularization: a comparison with fractional flow reserve. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:67–77.

Johnson NP, Toth GG, Lai D, Zhu H, Agostoni P, Appelman Y, et al. Prognostic value of fractional flow reserve: linking physiologic severity to clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1641–54. Comprehensive metaanalysis linking the value of fractional flow reserve to prognosis.

Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Siebert U, Ikeno F, van’ t Veer M, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213–24.

Fearon WF, Shilane D, Pijls NH, Boothroyd DB, Tonino PA, Barbato E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with stable coronary artery disease and abnormal fractional flow reserve. Circulation. 2013;128:1335–40.

De Bruyne B, Fearon WF, Pijls NH, Barbato E, Tonino P, Piroth Z, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI for stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1208–17.

Morris PD, Ryan D, Morton AC, Lycett R, Lawford PV, Hose DR, et al. Virtual fractional flow reserve from coronary angiography: modeling the significance of coronary lesions: results from the VIRTU-1 (VIRTUal Fractional Flow Reserve From Coronary Angiography) study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:149–57.

Park SJ, Ahn JM, Park GM, Cho YR, Lee JY, Kim WJ, et al. Trends in the outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention with the routine incorporation of fractional flow reserve in real practice. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3353–61.

Taylor CA, Fonte TA, Min JK. Computational fluid dynamics applied to cardiac computed tomography for noninvasive quantification of fractional flow reserve: scientific basis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2233–41. Provides a comprehensive description of the FFR CT technology.

Taylor CA, Steinman DA. Image-based modeling of blood flow and vessel wall dynamics: applications, methods and future directions. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:1188–203.

Wang KC, Dutton RW, Taylor CA. Improving geometric model construction for blood flow modeling. IEEE Eng Med Biol. 1999;18:33–9.

Taylor CA, Draney MT, Ku JP, Parker D, Steele BN, Wang K, et al. Predictive medicine: computational techniques in therapeutic decision-making. Comput Aided Surg. 1999;4:231–47.

Koo BK, Erglis A, Doh JH, Daniels DV, Jegere S, Kim HS, et al. Diagnosis of ischemia-causing coronary stenoses by noninvasive fractional flow reserve computed from coronary computed tomographic angiograms. Results from the prospective multicenter DISCOVER-FLOW (Diagnosis of Ischemia-Causing Stenoses Obtained Via Noninvasive Fractional Flow Reserve) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1989–97.

Min JK, Leipsic J, Pencina MJ, Berman DS, Koo BK, van Mieghem C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fractional flow reserve from anatomic CT angiography. JAMA. 2012;308:1237–45. Large scale multicenter study testing the diagnostic performance of FFR CT using measured fractional flow reserve as the reference standard.

Nørgaard BL, Leipsic J, Gaur S, Seneviratne S, Ko BS, Ito H, et al. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography in suspected coronary artery disease: the NXT trial (analysis of coronary blood flow using CT Angiography: next steps). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1145–55. Large scale multicenter study testing the diagnostic performance of FFR CT using the most updated analysis software with measured fractional flow reserve as the reference standard.

Leipsic J, Yang TH, Thompson A, Koo BK, Mancini GB, Taylor C, et al. CT angiography (CTA) and diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve: results from the Determination of Fractional Flow Reserve by Anatomic CTA (DeFACTO) study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:989–94. Document the importance of sufficient heart rate control and use of nitroglycerin for coronary CTA and FFR CT assessment.

Achenbach S, Manolopoulos M, Schuhback A, Ropers D, Rixe J, Schneider C, et al. Influence of heart rate and phase of the cardiac cycle on the occurrence of motion artifact in dual-source CT angiography of the coronary arteries. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2012;6:91–8.

Gaur S, Achenbach S, Leipsic J, Mauri L, Bezerra HG, Jensen JM, et al. Rationale and design of the HeartFlowNXT (HeartFlow analysis of coronary blood flow using CT angiography: Next sTeps) study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2013;7:279–88.

Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the task force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the european society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949–3003.

Nørgaard BL, Leipsic J, Achenbach S, Gaur S, Bezerra H, Jensen JM. Improved specificity of non-invasive fractional flow reserve from coronary CT angiography employing latest generation techniques and standardized image metrics. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr (Suppl). 2014;171 (abstract).

Gaur S, Bezerra HG, Lassen JF, Christiansen EH, Tanaka K, Jensen JM, et al. Fractional flow reserve derived from coronary CT angiography: variation of repeated analyses. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8:307–14.

Nørgaard BL, Gaur S, Leipsic J, Ito H, Miyoshi T, Park SJ, et al. Influence of coronary calcification on the diagnostic performance of CT angiography derived FFR in coronary artery disease: a substudy of the NXT trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1209–22.

Tanaka K, Bezerra HG, Gaur S, Attizzani GF, Bøtker HE, Costa MA, et al. Comparison between noninvasive (coronary computed tomography angiography derived) and invasive-fractional flow reserve in patients with serial stenoses within one coronary artery: a NXT Trial substudy. Ann Biomed Eng. 2015;in press.

Nørgaard BL, Jensen JM, Leipsic J. Fractional flow reserve derived from coronary CT angiography in stable coronary disease: a new standard in non-invasive testing? Eur Radiol. 2015;25:2282–90.

Curzen N, Rana O, Nicholas Z, Golledge P, Zaman A, Oldroyd K, et al. Does routine pressure wire assessment influence management strategy at co-ronary angiography for diagnosis of chest pain?: the RIPCORD study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:248–55.

Park SJ, Kang SJ, Ahn JM, Shim EB, Kim YT, Yun SC, et al. Visual-functional mismatch between coronary angiography and fractional flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:1029–36.

Toth G, Hamilos M, Pyxaras S, Mangiacapra F, Nelis O, Vroey D, et al. Evolving concepts of angiogram: fractional flow reserve discordances in 4000 coronary stenoses. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2831–8.

De Bruyne B, Hersbach F, Pijls NH, Bartunek J, Bech JW, Heyndrickx GR, et al. Abnormal epicardial coronary resistance in patients with diffuse atherosclerosis but “Normal” coronary angiography. Circulation. 2001;104:2401–6.

Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, Brennan JM, Redberg RF, Anderson HV, et al. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:886–95.

Lin GA, Dudley RA, Lucas FL, Malenka DJ, Vittinghoff E, Redberg RF. Frequency of stress testing to document ischemia prior to elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2008;300: 1765–73.

Patel MR, Dai D, Hernandez AF, Douglas PS, Messenger J, Garratt KN, et al. Prevalence and predictors of nonobstructive coronary artery disease identified with coronary angiography in contemporary clinical practice. Am Heart J. 2014;167:846–52.

Douglas PS, Pontone G, Hlatky MA, Patel MR, Norgaard BL, Byrne RA, et al. Clinical outcomes of fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography-guided diagnostic strategies vs usual care in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: the prospective longitudinal trial of FFRct: outcome and resource impacts (PLATFORM) study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3359–67. The first large-scale trial invastigating clinical outcomes and downstream resource utilization following FFR CT vs conventional ischemia testing.

Nørgaard BL, Hjort J, Gaur S, Hansson N, Bøtker HE, Leipsic J, et al. Clinical use of coronary computed tomography angiography derived fractional flow reserve (FFRCT) for decision making in stable coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;in press. The first real-world report on the diagnostic performance of FFR CT in CAD.

Hlatky MA, Saxena A, Koo BK, Erglis A, Zarins CK, Min JK. Projected costs and consequences of computed tomography-determined fractional flow reserve. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:743–8.

Kimura T, Shiomi H, Kuribayashi S, Isshiko T, Kanazawa S, Ito H, et al. Cost analysis of non-invasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomographic angiography in Japan. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2015;30:38–44.

Hlatky MA, De Bruyne B, Pontone G, Patel MR, Norgaard BL, Byrne RA, et al. Quality of life and economic outcomes of assessing fractional flow reserve with computed tomography Angiography: the PLATFORM study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2315–23. The first large-scale trial invastigating quality of life and economic aspects following FFR CT vs conventional ischemia testing. A substudy of the PLATFORM trial.

Nakazato R, Park HB, Berman DS, Gransar H, Koo BK, Erglis A, et al. Noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from computed tomography angiography for coronary lesions of intermediate severity: results from the DeFACTo study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:881–9.

De Bruyne B, Sarma J. Fractional flow reserve: a review: invasive imaging. Heart. 2008;94:949–59.48.

Abbara S, Arbab-Zadeh A, Callister TQ, Desai MY, Mamuya W, Thomson L, et al. SCCT guidelines for performance of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the society of cardiovascular computed tomography guidelines committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2009;3:190–204.

Min JK, Koo BK, Erglis A, Doh JH, Daniels DV, Jegere S, et al. Effect of image quality on diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive fractional flow reserve: results from the prospective multicenter international DISCOVER-FLOW study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2012;6:191–9.

Renker M, Schoepf UJ, Wang R, Meinel FG, Rier JD, Bayer II RR, et al. Comparison of diagnostic value of a novel noninvasive coronary computed tomography angiography method vs standard coronary angiography for assessing fractional flow reserve. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1303–8.

Coenen A, Lubbers MM, Kurata A, Kono A, Dedic A, Chelu RG, et al. Fractional flow reserve computed from noninvasive CT angiography data: diagnostic performance of an on-site clinician-operated computationa fluid dynamics algorithm. Radiology. 2015;274:674–83.

Nørgaard BL, Leipsic J. From Newton to the coronaries. Computational fluid dynamics has entered the clinical scene. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;in press.

Kim KH, Doh JH, Koo BK, et al. A novel noninvasive technology for treatment planning using virtual coronary stenting and computed tomography-derived computed fractional flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:72–8.

Liu SQ, Fung YC. Relationship between hypertension, hypertrophy, and opening angle of zero-stress state of arteries following aortic constriction. J Biomech Eng. 1989;111:325–35.

Choi G, Lee JM, Kim HJ, Park JB, Sankaran S, Otake H, et al. Coronary artery axial plaque stress and its relationship with lesion geometry: application of computational fluid dynamics to coronary CT angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1156–66. Introduction of coronary artery axial plaques forces for assessment of coronary artery disease.

Tang BT, Cheng CP, Draney MT, Wilson NM, Tsao PS, Herfkens RL, et al. Abdominal aortic hemodynamics in young healthy adults at rest and during lower limb exercise: quantification using image-based computer modeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H668–76.

Les AS, Shadden SC, Figueroa CA, Park JM, Tedesco MM, Herfkens RJ, et al. Quantification of hemodynamics in abdominal aortic aneurysms during rest and exercise using magnetic resonance imaging and computational fluid dynamics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:1288–313.

Acevedo-Bolton G, Jou LD, Dispensa BP, Lawton MT, Higashida RT, Martin AJ, et al. Estimating the hemodynamic impact of interventional treatments of aneurysms: numerical simulation with experimental validation: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:E429–30.

Cebral JR, Castro MA, Burgess JE, Pergolizzi RS, Sheridan MJ, Putman CM. Characterization of cerebral aneurysms for assessing risk of rupture by using patient-specific computational hemodynamics models. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:2550–9.

Cebral JR, Yim PJ, Lohner R, Soto O, Choyke PL. Blood flow modeling in carotid arteries with computational fluid dynamics and MR imaging. Acad Radiol. 2002;9:1286–99.

Milner JS, Moore JA, Rutt BK, Steinman DA. Hemodynamics of human carotid artery bifurcations: computational studies with models reconstructed from magnetic resonance imaging of normal subjects. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:143–56.

Tang BT, Fonte TA, Chan FP, Tsao PS, Feinstein JA, Taylor CA. Three-dimensional hemodynamics in the human pulmonary arteries under resting and exercise conditions. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:347–58.

Tang BT, Pickard SS, Chan FP, Tsao PS, Taylor CA, Feinstein JA. Wall shear stress is decreased in the pulmonary arteries of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: an image-based, computational fluid dynamics study. Pulm Circ. 2012;2:470–6.

Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1371–5.

Slager CJ, Wentzel JJ, Gijsen FJ, Thury A, van der Wal AC, Schaar JA, et al. The role of shear stress in the generation of rupture-prone vulnerable plaques. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2:401–7.

Zarins C, Giddens D, Bharadvaj B, Sottiurai V, Mabon R, Glagov S. Carotid bifurcation atherosclerosis: quantitative correlation of plaque localization with flow velocity profiles and wall shear stress. Circ Res. 1983;53:502–14.

Zarins CK, Zatina MA, Giddens DP, Ku DN, Glagov S. Shear stress regulation of artery lumen diameter in experimental atherogenesis. J Vasc Surg. 1987;5:413–20.

Gijsen FJ, Wentzel JJ, Thury A, Mastik F, Schaar JA, Schuurbies JC, et al. A new imaging technique to study 3-D plaque and shear stress distribution in human coronary artery bifurcations in vivo. J Biomech. 2007;40:2349–57.

Samady H, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, Suo J, Dhawan SS, Maynard C, et al. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011;124:779–88.

Chatzizisis YS, Jonas M, Coskun AU, Beigel R, Stone BV, Maynard C, et al. Prediction of the localization of high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques on the basis of low endothelial shear stress: an intravascular ultrasound and histopathology natural history study. Circulation. 2008;117:993–1002.

Papafaklis MI, Takahashi S, Antoniadis AP, Coskun AU, Tsuda M, Mizuno S, et al. Effect of the local hemodynamic environment on the de novo development and progression of eccentric coronary atherosclerosis in humans: insights from PREDICTION. Atherosclerosis. 2015;240:205–11.

Stone PH, Saito S, Takahashi S, Makita Y, Nakamura S, Kawasaki T, et al. Prediction of progression of coronary artery disease and clinical outcomes using vascular profiling of endothelial shear stress and arterial plaque characteristics: the PREDICTION Study. Circulation. 2012;126:172–81.

Kim HJ, Vignon-Clementel IE, Coogan JS, Figueroa CA, Jansen KE, Taylor CA. Patient-specific modeling of blood flow and pressure in human coronary arteries. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:3195–209.

van der Giessen AG, Wentzel JJ, Meijboom WB, Mollet NR, van der Steen AF, et al. Plaque and shear stress distribution in human coronary bifurcations: a multislice computed tomography study. EuroIntervention. 2009;4:654–61.

Jensen JM, Gormsen LC, Mølgaard H, Nørgaard BL. Noninvasive fractional flow reserve for the diagnosis of lesion specific ischemia: a case example. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2015;5:3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Bjarne Linde Nørgaard has received institutional research support from Edwards Lifesciences, Siemens and HeartFlow. Jonathon Leipsic has received speaker’s honorarium from GE, and is consultant to and has received institutional research support from HeartFlow. Bon-Kwon Koo has received institutional research support from St. Jude and HeartFlow. Christopher K. Zarins and Charles A. Taylor are co-founders, employees and shareholders of HeartFlow, Inc., which provides the FFRCT service. Jesper Møller Jensen has received speaker’s honorarium from Bracco Imaging. Niels Peter Sand declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any animal or human studies that would need informed consent.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardiac Computed Tomography

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nørgaard, B.L., Leipsic, J., Koo, BK. et al. Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Derived Fractional Flow Reserve and Plaque Stress. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep 9, 2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12410-015-9366-5

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12410-015-9366-5