Abstract

This paper looks into various models that address strategic behavior in the supply of gas by the Mexican monopoly Pemex. The paper has three very strong technical results. First, the netback pricing rule for the price of domestic natural gas (based on a Houston benchmark price) leads to discontinuities in Pemex’s revenue function. Second, having Pemex pay for the gas it uses and the gas it flares increases the value of the Lagrange multiplier associated with the gas processing constraint. Third, if the gas processing constraint is binding, having Pemex pay for the gas it uses and flares does not change the short run optimal solution for the optimization problem, so it will have no impact on short-run behavior. These results imply three clear policy recommendations. The first is that the arbitrage point be fixed by the amount of gas Pemex has the potential to supply in the absence of processing and gathering constraints. The second is that Pemex be charged for the gas it uses in production and the gas it flares. The third is that investment in gas processing and pipeline should be in a separate account from other Pemex investment.

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Artikel betrachtet verschiedene Modelle, die sich mit strategischem Verhalten in der Gasversorgung durch den Mexikanischen Monopolisten Pemex befassen. Der Artikel hat drei sehr starke technische Ergebnisse. Erstens führt die „Netback“-Preisbildungsregel für den Preis von heimischem Erdgas (auf der Basis eines Houston-Richtpreises) zu Diskontinuitäten in der Ertragsfunktion von Pemex. Zweitens erhöht, wenn man Pemex das von ihm verbrauchte Gas und das von ihm abgefackelte Gas bezahlen lässt, dieses den Wert des Lagrange-Multiplikators in Verbindung mit der Gasverarbeitungsbeschränkung. Drittens ändert, wenn die Gasverarbeitungsbeschränkung bindend ist, der Umstand, dass man Pemex das verbrauchte und abgefackelte Gas bezahlen lässt, nicht die kurzfristige optimale Lösung für das Optimierungsproblem, sodass sie keinen Einfluss auf das kurzfristige Verhalten hat. Diese Ergebnisse implizieren drei klare politische Empfehlungen. Die Erste besteht in der Festlegung des Arbitrage-Punktes anhand der Gasmenge, die Pemex ohne Verarbeitungs- und Gewinnungsbeschränkungen liefern kann. Die Zweite besteht darin, dass Pemex für das in der Produktion verbrauchte Gas und für das abgefackelte Gas bezahlt. Die Dritte besteht darin, dass Investitionen in Gasverarbeitung und Pipelines von anderen Pemex-Investitionen getrennt bilanziert werden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Little and Mirrlees (1968), p. 92.

See Appendix for background on the Mexican natural gas market.

See Adelman (1963).

This relies on the fact that the Houston hub is has a liquid market of future contracts to hedge against externalities.

The arbitrage point is the place where northern and southern gas flows meet, and where northern and southern gas prices coincide.

See Little and Mirrlees (1968) p. 92.

In general, the demand curve faced by Pemex under the pricing rule is downward sloping in regions where the demand is positive and there are no mass points. This is because increasing sales move the point of arbitrage north. The price is constant in intervals of demand that correspond to mass points. This is because Pemex can sell more gas without moving the point of arbitrage. Finally, there are intervals in the pipeline where there are gaps. The demand curve faced by Pemex is discontinuous at these points; an infinitesimal shift in supply will move the point of arbitrage by a substantial amount and this leads to a discontinuity.

Pemex’s transportation network covers most of the country with the exception of the northwest and north-pacific.

CRE’s original role in oversight the electricity industry is largely limited to issuing permits and approving wheeling and buyback charges for private sector generators. The Secretary of Finance (Hacienda) has a decisive role in setting retail tariffs and government guarantees, while the CFE predominates in the definition of bids for independent power projects, and contract contents.

References

Adelman MA (1963) The supply and price of natural gas. Blackwell, Oxford

Brito DL, Rosellón J (2002) Pricing natural gas in Mexico: an application of the Little-Mirrlees rule. Energy J 23(3):81–93

Brito DL, Rosellón J (2005) Price regulation in a vertically integrated natural gas industry: the case of Mexico. Rev Netw Econ 4(1)

Comisión Reguladora de Energía (1996) Directiva sobre la determinacion de precios y tarifas para las actividades reguladdas en materia de Gas Natural. Mexico. http://www.cre.gob.mx

Little IMD, Mirrlees JA (1968) Manual of industrial project analysis in developing countries. Development Centre of the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Paris

Rosellón J, Halpern J (2001) Regulatory reform in Mexico’s natural gas industry: liberalization in context of dominant upstream incumbent. Policy Research Working Paper 2537. The World Bank

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper was supported by the Comisión Reguladora de Energía through a grant to Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE). The second author also acknowledges support from the Repsol-YPF-Harvard Kennedy School Fellows program, and the Fundación México en Harvard.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Background of the Mexican Natural-Gas Industry

Appendix: Background of the Mexican Natural-Gas Industry

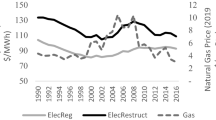

In 1992 the Mexican government initiated modest changes to permit entry of private participants in power generation, and a more ambitious reform in natural gas was begun in 1995. Before this, state companies had controlled energy activities: Pemex in the oil and gas sector, and Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) and Luz y Fuerza del Centro (LFC) in the electricity industry. So far, no decisions have been made on private participation and structural reform in gas production, oil extraction and processing, and production of petrochemicals. Structural reform of the electricity sector has been postponed.

The natural gas sector in Mexico was reformed in 1995 through an amendment of the Regulatory law of Constitutional Article 27 (the Gas Law) to allow private investment in new transportation projects and distribution, storage, and commercialization of natural gas. The law established principles for developing the country’s natural gas industry. Putting these principles in practice required creating a regulatory framework that specified the organization, operation, and regulations of the industry. Such a framework was designed in 1995 and presented in the Reglamento de Gas Natural. It explicitly took into account noncompetitive conditions in production since Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) would keep its statutory monopoly in gas exploration and production, and focus on increasing natural gas production and maintaining its existing large transportation network of more than 9000 kilometers (see Fig. 11).Footnote 14

A new regulatory institution, Comisión Reguladora de Energía (CRE), was created in 1993 to provide limited regulatory oversight of private investment in power generation.Footnote 15 The CRE’s mandate was expanded and clarified in 1995 in tandem with the natural gas reforms. Since then, the CRE has ample regulatory powers in the natural gas industry, including attributions to regulate prices, and grant distribution and transportation concessions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brito, D.L., Rosellón, J. Strategic Behavior and International Benchmarking for Monopoly Price Regulation: The Case of Mexico. Z Energiewirtsch 34, 163–177 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12398-010-0023-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12398-010-0023-z