Abstract

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic, neuromuscular disease caused by deletions and/or mutations in the survival of motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene leading to reduced SMN protein levels. Nusinersen, an intrathecally administered antisense oligonucleotide therapy that increases SMN protein levels, is approved for use in adult and pediatric patients with SMA. Data to inform real-world patient adherence and persistence to nusinersen are limited, with disparities in the population with SMA, study design, and results. The objective of this study is to characterize real-world nusinersen adherence and persistence in patients with SMA.

Methods

This retrospective study examined nusinersen adherence and persistence over a 2-year period in patients with SMA in the USA from the IQVIA PharMetrics Plus claims database. Patients were followed from the date of first evidence of nusinersen treatment (occurring after 1 July 2017) until the end of the study period (31 December 2019) or end of continuous pharmacy and medical benefit enrollment, whichever came first. Subgroup analyses for nusinersen adherence and persistence were performed on the basis of age and presence or absence of spinal complications.

Results

The final cohort consisted of 179 patients with SMA treated with nusinersen. Adherence to nusinersen treatment was 41% at 56 weeks and 39% at 104 weeks. In the base-case persistence analysis, there was a decrease in persistence before 6 months (67%) and further decline at 1 (57%) and 2 years (55%). Patients with spinal complication versus without had numerically higher persistence with nusinersen.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that adherence and persistence to nusinersen treatment appear low. Demographic (age ≥ 18 years) and clinical factors (no spinal complications) may contribute to nusinersen treatment discontinuation. Future research should explore possible reasons for low adherence and persistence to nusinersen treatment, such as clinical or logistical factors, patient preferences, and payer restrictions.

Plain Language Summary

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare, genetic disease that causes patients to lose motor neurons over time. This makes tasks that involve movement control like walking and talking more difficult. SMA can be treated, but it is important that patients receive their scheduled doses of medicine as prescribed and stay on treatment. Nusinersen (SPINRAZA®) is a treatment for SMA that is given as an intrathecal injection into the cerebrospinal fluid of the spine. Patients receive six doses of nusinersen in the first year. After the first year, patients receive three doses every year for life.

This study looked at whether patients received their scheduled doses, also called adherence, and how many patients remained on treatment, or persistence, over two years. This study involved 179 nusinersen-treated patients with SMA and used data from US health insurance plans. After 56 weeks of treatment, 41% of patients were adherent. After 104 weeks, 39% were adherent. After 6 months, 67% of patients were still on treatment. After 1 year, 57% were still on treatment. After 2 years, 55% of patients were still on treatment. The study showed that a low number of patients with SMA, particularly those older than 18 years with no spinal problems, remained on nusinersen for the intended time and received the treatment as prescribed. Future studies will look at possible reasons for low adherence and persistence to nusinersen, which may include difficulties traveling to a clinic or scheduling a visit, patient preference, or insurance restrictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic, progressive neuromuscular disease that causes muscle weakness and disease-related complications affecting the entire body. |

Limited data exist to inform real-world patient adherence and persistence to nusinersen, a disease-modifying therapy approved for use in the treatment of SMA in adult and pediatric patients. |

The current study aims to characterize the real-world adherence and persistence to nusinersen among patients with SMA using a large claims database in the USA. |

Adherence to nusinersen treatment was 41% at 56 weeks and 39% at 104 weeks, and treatment persistence was 57% at 56 weeks and 55% at 104 weeks in the base-case analysis. |

The findings from this study suggest that real-world adherence and persistence to nusinersen treatment appear low; these results highlight potential barriers associated with this SMA treatment that can be further explored. |

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare, severe, genetic, neuromuscular disease that causes muscle atrophy and disease-related complications affecting the whole body [1, 2]. The estimated global incidence of SMA is 1 in 10,000 live births, with an estimated prevalence of 1 to 2 per 10,000 people [3]. In the USA, the prevalence of SMA is 8.5 to 10.3 per 100,000 live births [4]. SMA is caused by deletions and/or mutations of the survival of motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, leading to reduced levels of the survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein and subsequent motor neuron loss [5]. A second SMN gene, SMN2, produces low levels of functional SMN protein that are insufficient to compensate for deficiency in SMN1 [6]. SMA ranges in disease severity, and traditionally patients are classified into five subtypes (types 0–4 SMA, with lower numbers indicating greater severity) based on age at symptom onset and highest motor milestone achieved [7,8,9]. Type 0 is diagnosed in neonates and is usually fatal at birth [7, 8]. Clinical symptoms of types 1, 2, and 3 SMA usually manifest at < 6 months, 6 to 18 months of age, and after 18 months of age, respectively. In the absence of treatment, patients with type 1 SMA are unable to sit without support, patients with type 2 SMA can sit but are unable to stand or walk unassisted, and patients with type 3 SMA are able to achieve the ability to stand and walk [8]. Regardless of disease severity, management of SMA requires a multidisciplinary approach [10, 11].

Between 2016 and 2020, three disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for SMA were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Commission. All three DMTs increase full-length SMN protein levels via distinct mechanisms and use different routes of administration. Nusinersen (SPINRAZA®) is an intrathecally administered, SMN2-targeting antisense oligonucleotide therapy [12, 13] approved to treat children (including newborns) and adults with SMA [12, 14]. Treatment with nusinersen consists of four loading doses during the first 2 months (days 1, 14, 28, and 58) prior to maintenance doses administered every 4 months [14]. Onasemnogene abeparvovec (ZOLGENSMA®) is a one-time intravenous gene therapy that delivers a functional copy of the SMN1 gene to motor neurons [15, 16]. Risdiplam (EVRYSDI®) is a daily oral treatment designed to selectively modify splicing of SMN2 pre-mRNA [17, 18]. Early treatment with DMTs has been shown to increase treatment efficacy for patients with SMA, which has led to the inclusion of SMA in several newborn screening programs [19]. The phase 3 CHERISH trial (NCT02292537) enrolled children with SMA aged 2 to 12 years who could sit but not walk independently and who had a Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded (HFMSE) score of 10 to 54 at screening [20]. In CHERISH, an increase from baseline in HFMSE was observed in patients treated with nusinersen for 6 months, and a greater improvement was found when treatment lasted for 15 months [20]. These results suggest that in addition to early intervention, when receiving treatment with nusinersen, long-term adherence to the dosing schedule may be important to receive maximum clinical benefits.

Nusinersen is administered by repeated intrathecal injections performed via lumbar puncture at a hospital or specialized facility, which may impact treatment adherence. The FDA-approved dosing schedule of nusinersen requires six doses in the first year and three doses annually in subsequent years over a lifetime [21]. Obstacles to treatment adherence, which entails acting in accordance with both medication dosage and schedule within a specified time interval, and persistence, which entails continuing use of the prescribed medication, arise from a variety of factors. These include the requirement for repeated intrathecal injections, the cost and burden of traveling to treatment administration sites, as well as potential risk of infection or center closure due to a global pandemic [22]. Logistical issues associated with scheduling treatment and the high cost of nusinersen may limit patients’ access to treatment [23].

Data to inform real-world patient adherence and persistence to nusinersen are currently limited to two published studies [24, 25]. In this retrospective study, we examined real-world nusinersen adherence and persistence over a 2-year period in patients with SMA from a large claims database in the USA.

Methods

Data Source

This retrospective cohort analysis used data from the IQVIA PharMetrics Plus claims database. The database consists of fully adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims that are submitted to providers by health plans for reimbursement, which allow for the tracking of enrolled patients across all sites of care for more than 190 million unique enrollees in health plans in the USA [26]. PharMetrics Plus provides cost-related variables including payment amounts, demographic variables such as age and gender, and treatment variables including diagnosis and procedure codes. Additionally, the database is representative of the commercially insured US national population for patients under 65 years of age. Claims records from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019 were evaluated in this study. All data are compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act to protect patient privacy. A data use agreement with PharMetrics Plus allows our researchers to publish the results of analyses with their data in manuscripts. The study is exempted from Institutional Review Board review because only deidentified data were used.

Patient Population and Study Design

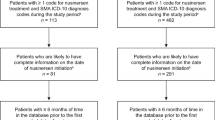

Claims of patients with SMA who were treated with nusinersen after 1 July 2017 were selected for inclusion in this analysis. This date was chosen instead of the FDA’s approval of nusinersen on 23 December 2016 in an effort to exclude claims from patients who received treatment with nusinersen through Biogen’s nusinersen early access program (EAP) (Fig. 1). The EAP provided access to nusinersen for patients with infantile-onset SMA (consistent with type 1 SMA) before commercial availability of the treatment [27]. However, nusinersen access via the EAP was confounded in some US sites owing to administrative funding-related issues [27]. Therefore, the EAP data may not be generalizable to a real-world population that relies predominantly on health insurance to afford treatment, which may create barriers to adherence and persistence to nusinersen treatment. To ensure that the study sample did not include patients who received nusinersen through the EAP, patients classified as having received nusinersen before 1 July 2017 by specific codes or an algorithm involving non-specific codes (Supplemental Fig. 1) were excluded from the analysis. The algorithm used in these analyses involved codes for non-specific biologics and spinal puncture procedures because there is often a time period where specific codes for new treatments are unavailable, particularly in the time period immediately after FDA approval. Patients with claims with pregnancy-related International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes (Supplementary Table 1) were also excluded from the analysis to avoid including claims from prenatal SMA screening.

Patients were followed from the index date (date of first nusinersen treatment; day 0) until the end of the study period (31 December 2019) or the end of continuous pharmacy and medical benefit enrollment, whichever came first (follow-up period). Continuous enrollment in pharmacy and medical benefits was checked monthly. Patients with SMA were identified by at least one inpatient or at least two outpatient claims with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, SMA diagnosis codes on distinct service dates ≥ 30 days apart (Supplementary Table 1). Patients treated with nusinersen were identified by specific nusinersen-treatment procedure codes available after January 2018 (Supplementary Table 1) or an algorithm based on codes for non-specific biologics, spinal punctures, and a paid amount of at least $100,000 (Supplementary Fig. 1). For inclusion in the analysis, patients must have had ≥ 30 days of continuous enrollment after the first dose of nusinersen or first intrathecal procedure (index date). Patients ≥ 1 year of age were required to have ≥ 6 months of pre-index continuous enrollment (pre-index period). Minimum pre-index continuous enrollment was not required for patients < 1 year of age; the pre-index period for these patients was the period from first administrative claim to index date and includes all claims available before the index date.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

Patient demographics were examined at the index date, while clinical characteristics were examined using all claims in the pre-index period. Claims dates were defined as the date on which services began for inpatient services or date of service for same-day services, office visits, or outpatient services. Adherence and persistence were descriptively examined at 24, 56, and 104 weeks after initiation of nusinersen treatment. At 24, 56, and 104 weeks, patients should have received at least five, at least seven, and at least 10 doses of nusinersen, respectively, on the basis of the FDA-approved dosing schedule. Multiple events occur at the 24-week timepoint: patients receive their first maintenance dose, and some health plans limit their initial approval of nusinersen to 24 weeks in their medical policies [21]. Reapproval may be contingent upon documented response to treatment as shown by increasing or stabilizing motor function, depending on the health plan [22]. Continued nusinersen treatment is contingent on reapproval and may represent a barrier to adherence and persistence for patients and their families. Outcome measurement at 104 weeks (2 years) aligns with the follow-up period used in the study by Gauthier-Loiselle et al. [25].

Older age may be associated with higher incidence of adverse events from lumbar puncture, as one study found that older children (8–14 years) with SMA had a higher incidence of adverse events compared with younger children (2–7 years) [28]. The incidence of adverse events may have an influence on adherence and persistence. To investigate this concept further, a subgroup analysis based on patient age (< 18 years versus ≥ 18 years) was performed. In addition, it is hypothesized that spinal complications would influence the adherence and persistence of patients on nusinersen, given that nusinersen is administered via intrathecal injection. Therefore, a subgroup analysis was performed according to the presence of spinal complications (patients with versus without spinal complications). A spinal complication was defined as the presence of lordosis, spondylolisthesis, kyphosis, scoliosis, or scoliosis correction surgery during the pre-index period and was identified by diagnostic codes (Supplementary Table 1).

Treatment Adherence

Treatment adherence was defined as the percentage of patients receiving at least the expected number of nusinersen doses at each dosing interval [29]; the dosing regimen was per FDA label, and the follow-up period was up to 2 years. Patients were only assessed if they had continuous enrollment throughout the specific period being examined, at a minimum. Grace periods of +7 days for each loading dose received and +28 days for each maintenance dose received were used for the adherence analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Grace periods were cumulative, which allowed for an additional 5.3 weeks for patients to receive five doses compared with the dosing schedule on the FDA label. Treatment adherence was further analyzed by subgroups of age and spinal complications.

Treatment Persistence

Treatment persistence was defined as the percentage of patients who remained on nusinersen; the follow-up period was up to 2 years. Patients were considered as discontinued from treatment if the following two criteria were met (Supplementary Fig. 3). First, the patient missed two consecutive doses on the expected dosing schedule per FDA label. Second, the patient had continuous enrollment through the date of the second missed dose; this stipulation ensured that patients were designated as discontinued only if they remained observable in the database during the assessment period. Patients who did not have follow-up through the two missed doses were censored when their continuous enrollment terminated or at the end of the study period, whichever came first. The discontinuation date was defined as the expected date of the first missed dose. In the base-case analysis, grace periods of +7 days for each loading dose received and +28 days for each maintenance dose received were used (Supplementary Fig. 3). A sensitivity analysis was performed using a discontinuation definition of one missed dose and grace periods of +7 days for each loading dose received and +60 days for each maintenance dose received. Treatment persistence was further analyzed by subgroups of age and spinal complications. A Kaplan–Meier curve was plotted to examine time to discontinuation, and a log-rank test was performed to examine differences in time-to-discontinuation Kaplan–Meier curves. A p value of < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used to construct the analytic dataset and perform all analyses.

Results

Patient Attrition and Patient Characteristics

Of the 1488 patients who had evidence of a diagnosis of SMA, 1413 (95%) had no pregnancy-related claims and 339 (23%) had evidence of nusinersen treatment at any point during the study period after 1 July 2017 (Table 1). The final analytic cohort for analysis consisted of 179 patients with SMA treated with nusinersen (Table 1) after all inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied.

Overall, 59.2% of the patients were ≤ 18 years of age. The mean (SD) age at treatment was 17.6 (14.4) years, and the mean (SD) follow-up was 17.3 (9.7) months (Table 2). Within the four age categories, 73 patients were adults (40.8%; ≥ 18 years), 56 patients were adolescents (31.3%; 13–17 years), and the remainder were children (19.0%; 2–12 years) or infants (8.9%; < 2 years). Of the total cohort, 95 patients (53.1%) were female, and 99 patients (55.3%) had spinal complications during the study period. The most common spinal complication was scoliosis, which was observed in 82 patients (45.8%); 12 patients (6.7%) had scoliosis correction surgery during the study period. Of the cohort, 173 patients (96.6%) had commercial or self-insured coverage. Most patients (41.3%) were from the Midwest region of the USA (Table 2).

Nusinersen Treatment Adherence

Of the 171 patients with sufficient follow-up at week 8, only 80 patients (47%) had completed the four loading doses expected per the FDA label schedule (within 8 weeks from initiation of treatment, with grace periods for each dose). The proportion of patients with sufficient follow-up declined further during the maintenance phase such that nusinersen adherence was determined from 149, 118, and 57 patients of the cohort at 24, 56, and 104 weeks, respectively. Adherence to the nusinersen treatment declined throughout the maintenance phase, with 46% (68/149), 41% (48/118), and 39% (22/57) of patients demonstrating adherence at 24, 56, and 104 weeks, respectively (Fig. 2).

In the subgroup analysis by age, nusinersen adherence during the first year of treatment (≤ 6 expected doses) was numerically lower in patients < 18 years of age compared with patients ≥ 18 years of age. In contrast, after 1 year of nusinersen treatment, adherence was numerically higher in patients < 18 years of age compared with patients ≥ 18 years of age (Fig. 3A). A greater proportion of patients with spinal complications adhered to nusinersen treatment throughout the 104-week period compared with patients without spinal complications (Fig. 3B).

Proportion of adherent patients by expected number of doses: analysis by age group (A) and spinal complications (B). *Per product label and grace period (7 days for loading doses, 28 days for maintenance doses). †All patients represents the total number of patients with the corresponding follow-up time

Nusinersen Treatment Persistence

In the base-case analysis, treatment persistence was 67% at 24 weeks, 57% at 56 weeks, and 55% at 104 weeks (Fig. 4). In the sensitivity analysis, treatment persistence was 53% at 24 weeks, 42% at 56 weeks, and 35% at 104 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 4). Subgroup analysis by age revealed that patients < 18 years of age had similar persistence to nusinersen treatment as patients ≥ 18 years of age (Fig. 5A). Patients with spinal complications had higher persistence than those without spinal complications (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

The findings from this study suggest that adherence and persistence to nusinersen treatment are low. Adherence to nusinersen treatment was 41% at 56 weeks (year 1) and 39% at 104 weeks (year 2), despite grace periods of +7 days for each loading dose received and +28 days for each maintenance dose. Elman et al. conducted an analysis of a retrospective chart review using a limited set of Electronic Medical Record (EMR) data from nine Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) clinics and used the same grace periods as this study. In contrast to our findings, Elman et al. found that 58 patients (67% of cohort) were adherent at 24 months and 92% of doses were administered on schedule when doses were considered cumulatively across all patients [24]. Certain study design aspects of the analysis by Elman et al. may have contributed in part to the differences in the adherence observed compared with this analysis. The EMR data were sourced from nine MDA clinics, but no information was presented on how these nine clinics were chosen for the analysis or how the treatment was paid for. Therefore, it is unknown whether the patient population from the MDA clinics experienced obstacles to nusinersen treatment access associated with insurance coverage. Despite approval by the FDA, prior insurance authorization, reapproval, and a lack of consensus on patient eligibility for treatment can hinder access to nusinersen treatment for patients with SMA in the USA [23]. In addition, the study by Elman et al. included patients ≥ 18 years of age. The study population primarily consisted of patients with types 2 and 3 SMA, while 6% of patients had type 1 SMA. Patients with types 2 and 3 SMA are older and have fewer symptoms than patients with infantile-onset SMA (type 1 SMA), which may have an impact on adherence and persistence. In addition, the study by Elman et al. had a smaller sample size (N = 86), and adherence results were not stratified by length of follow-up. Ten of 86 patients (12%) were still being followed at 2 years.

Similar to the results of the present analysis, a prior retrospective claims database analysis conducted by Gauthier-Loiselle et al. that included 324 patients with SMA found that nusinersen adherence was low; more than 50% of patients missed ≥ 1 dose by 24 months [25]. Notably, compared with Elman et al. and the present analysis, Gauthier-Loiselle et al. used a stricter definition of adherence with grace periods of ±7 days for each loading dose received and ±14 days for each maintenance dose [25]. Gauthier-Loiselle et al. also excluded patients who did not complete all four loading doses [25]. The strict criteria employed in the Gauthier-Loiselle study may not fully encompass real-world treatment patterns and may be considered a limitation. Conversely, Elman et al. defined a discontinuation period such that an individual could go without treatment for up to 10 months [24]. This study, however, defined grace periods and discontinuation criteria that are stricter than those of Elman et al. yet more lenient than those of Gauthier-Loiselle et al., thus reflecting more real-world treatment patterns. In addition, the analysis by Gauthier-Loiselle et al. did not incorporate statistical comparison of subgroups or stratification of adherence results by length of the follow-up period [25]. Although both studies were completed in the USA, Elman et al. examined a smaller sample size (N = 86) than the study by Gauthier-Loiselle et al. (N = 324), which may have contributed to the discrepancy in results [24, 25]. In this base-case persistence analysis, a decrease in persistence before 6 months (67%) and further decline at 1 (57%) and 2 years (55%) was observed. Importantly, the analyses censored patients without sufficient follow-up at the respective timepoints, which accounts for patients who drop out of the database owing to changes in insurance coverage.

As most of the patients (96.6%) were commercially or self-insured, the drop in persistence at 6 months may in part be explained by requirements around prior authorization reapproval for nusinersen coverage at that time. Gauthier-Loiselle et al. reported data from all payment types, including commercial insurance plans, Medicare Part D, Medicaid, and other assistance programs, but the breakdown of insurance plans is not publicly available [25].

Elman et al. found that 92% of patients with SMA were persistent with nusinersen treatment at 24 months [24]. In contrast, and similar to the present study results, Gauthier-Loiselle et al. [25] reported that < 50% of patients, regardless of SMA type, remained on treatment 2 years after starting nusinersen. Notably, in the present study, persistence dropped from 67% at 6 months to 55% at 2 years. This decrease in persistence may better reflect the actual rate of discontinuation due to adverse events or lack of efficacy. The sustained persistence observed between 6 months and 2 years may have been attributed to the longer dosing intervals and grace periods after 24 weeks, which required less frequent clinic visits for an intrathecal injection.

This study used the same discontinuation definition as Elman et al. [24], and the present base-case persistence estimates may reflect the larger sample size of this study. Furthermore, the present analysis used real-world data from adjudicated insurance claims across the USA, whereas Elman et al. included EMR data from 86 patients from nine pre-selected MDA-associated clinics. The discontinuation definition from Elman et al. (i.e., allowing for two missed doses) allowed patients to go without nusinersen treatment for up 10 months. However, a grace period of that length may be more lenient than what is normally seen in adherence and persistence analyses. For reference, a persistence study for a daily oral medication will often mark a patient as discontinued after a treatment gap of 90 days [30]. There are additional studies in SMA that showed comparatively lower discontinuation rates (5–10%) during the first 12–24 months of treatment, with relatively high adherence [31,32,33,34,35]. However, these studies were center based and either did not include or did not have as rigid definitions of adherence and persistence, as these were not the main outcomes for their analyses when compared with Elman et al. [24], Gauthier-Loiselle et al. [25], or this study.

The sensitivity analysis carried out in this study examined how sensitive our persistence algorithm is to changes in certain parameters, such as changing the discontinuation definition from two missed doses to one. As our base-case analysis was more lenient by allowing two consecutively missed doses, a stricter definition of discontinuation was used in the sensitivity analysis, wherein the patients were considered to have discontinued treatment after missing a single dose with grace periods of +7 days for each loading dose and +60 days for each maintenance dose received. The lower persistence estimates in the sensitivity analysis show that the algorithm is behaving as intended and that there was a group of patients who skipped one dose but restarted treatment afterwards. These patients are designated as discontinued in the sensitivity analysis, but not in the base-case analysis in which patients had to have missed two consecutive doses.

In this study, demographic (age ≥ 18 years) and clinical (absence of spinal complications) factors that may contribute to nusinersen treatment discontinuation were identified; however, further research is needed to confirm these findings. Patients ≥ 18 years of age had higher adherence within the first year of treatment compared with those < 18 years of age. However, in the second year of treatment (≥ 7 doses), there was a reversal such that patients < 18 years of age were more adherent than the older patients. In contrast, the persistence results were similar across both age groups over time. A systematic review of patient characteristics reported that age does not have a linear relationship with medication adherence in different therapeutic areas; instead, the peak of adherence is at middle-to-older ages, and lower adherence is exhibited by very young and very old individuals [36]. Such differences in treatment adherence by age group are difficult to explain since previous studies have not examined this in SMA.

The subgroup analysis of patients with versus without spinal complications suggested that patients with spinal complications displayed better adherence to the nusinersen dosing schedule. Having spinal complications or younger age of onset may be a reflection of more severe SMA, and these patients and their families may require more interactions in the healthcare setting that lead to higher adherence. Our analysis used diagnosis codes to identify patients with spinal complications, which assumes that providers submitted a claim with the diagnosis codes that we queried. This approach may misclassify patients but is a limitation of all administrative claims databases without access to provider notes. Importantly, the analyses censored patients without sufficient follow-up at the respective timepoints, which accounted for patients who dropped out of the database owing to changes in insurance coverage. As a result, at later timepoints (88 and 104 weeks), the observable sample size decreased owing to loss of patients to follow-up, which may reduce the generalizability of the results.

This study has several limitations. A lower number of patients than expected (23%) were treated with nusinersen during the study period. At the time this study was conducted, nusinersen was the first FDA-approved DMT for the treatment of SMA [37]. Natural history studies have found that children with type 1 SMA, who represent 60% of SMA diagnoses, had an average lifespan of < 2 years [38, 39]. The small proportion of treated children in our sample may have reflected the prevalence of SMA before additional treatments were approved and therefore the differences in life expectancy for various SMA types. This study may have underrepresented SMA type 1 patients owing to their lower life expectancy (< 2 years) compared with patients with later onset types of SMA (types 3–4) whose life expectancy is closer to the general population. Patients with later onset SMA may be less likely to seek treatment as they have less severe disease and may not meet the prior authorization criteria for nusinersen treatment initiation. The aforementioned reasons may have further contributed to the overall low percentage (23%) of patients treated with nusinersen observed in our study. The study period took place from nusinersen approval through 2 years after approval, and adoption of this new treatment may have been slow. There is a possibility that if additional data were added after this time, there would be a higher percentage of patients treated with nusinersen. The algorithm used to identify nusinersen treatment utilized every known code for nusinersen claims, including nusinersen-specific and nonspecific codes. Further, the algorithm searched for claims that consisted of a non-specific biologic code in conjunction with a claim for a lumbar puncture with a high dollar amount (> US $100,000) to identify patients who received nusinersen. Nonspecific procedure codes were not previously validated; therefore, our analysis could have misclassified another treatment as nusinersen if it was administered intrathecally with a paid amount of greater than US $100,000. It is also possible that not all providers reported nusinersen claims for reimbursement in the PharMetrics Plus database; however, given the high cost of nusinersen, there is a financial incentive for the healthcare provider to report these data correctly [40]. There is also a possibility that claims could have been rejected by commercial health plans owing to payer restrictions that would be excluded from the database. Therefore, payer restrictions can impact treatment adherence and persistence in countries with universal healthcare compared with private insurance in the USA, and these differences should be considered. As with all analyses utilizing administrative claims as a source of data, there is the general limitation of potential upcoding and miscoding, and there is always the possibility of losing data during the transfer from health insurance to the commercial claims data vendor, such as PharMetrics Plus. This analysis includes a relatively short follow-up, although patients without sufficient follow-up were excluded from adherence and persistence calculations at each time point. The mostly commercially insured study population and their geographic distribution may confer bias and may not be generalizable to the US population with SMA. In comparison to the US census, the PharMetrics Plus database slightly overrepresents the US population in the Midwest and South and underrepresents the population in the West. There is evidence indicating that socioeconomic status and social support may have a positive impact on adherence while belonging to an ethnic minority may have a negative impact on adherence [41,42,43]. However, the PharMetrics Plus dataset does not include data on socioeconomic status, race, or enrollee income variables, so the impact of these factors on nusinersen adherence and persistence could not be investigated in the current analysis. In addition, the PharMetrics Plus database did not have sufficient data to characterize the SMA type of patients, as many patients had ICD codes for multiple SMA types. This is a limitation of many real-world datasets, including the PharMetrics Plus database, which provide limited clinical data on enrollees. Furthermore, since PharMetrics Plus includes claims submitted from providers to payers for reimbursement, the risk of missing data is minimized owing to a financial incentive for providers to submit complete information. In the future, using data that provide disease-specific measures and applying advanced regression models to examine the outcome of interest while controlling for confounding variables could be useful to understand more nuanced disease-related questions. Lastly, reasons for low adherence and persistence, such as difficulties scheduling and accessing clinics or other logistical issues, are not available in this study’s administrative claims data source but should be explored in future analyses.

Although treatment with nusinersen results in significant improvements in event-free survival and motor milestones, potential complications associated with the lumbar puncture procedure may arise in this patient population [28]. Lumbar puncture is routinely performed for diagnostic purposes in pediatric patients, but it is not performed frequently for pediatric patients with SMA [28]. Furthermore, it is likely that clinical trials of nusinersen treatment offer more reliable access to treatment following the dose schedule than patients may encounter in the real-world setting. Interruptions in nusinersen treatment lead to lower cerebrospinal fluid levels of nusinersen that may affect efficacy [44]. Regimens to restore optimal cerebrospinal fluid nusinersen levels have been developed and are dependent on the time since the last treatment was administered [44, 45]. In addition, a recently described surgical modification of the traditional scoliosis surgery incorporates a laminotomy at L3-L4 to provide intrathecal access for future nusinersen injections for patients with SMA [46]. However, with three DMTs for SMA currently available, patients and their caregivers now have several options to treat SMA. Some patients with SMA have declined nusinersen treatment because of the requirement for repeated lumbar punctures [28]. Discrete choice experiment (DCE) studies have recently reported that treatment administration is an important attribute in treatment selection [47]. Patients with SMA prefer to avoid repeated intrathecal injections compared with other administration options [48]. As such, drug delivery via routes other than intrathecal injection may improve treatment adherence and persistence in patients with SMA. Improving SMA treatment adherence and persistence is important both from a medical and economic standpoint, as it has been previously shown that discontinuation and non-adherence to nusinersen treatment is associated with greater frequency of SMA-related comorbidities (e.g., feeding difficulties, dyspnea and respiratory anomalies, and muscle weakness), greater health care resource utilization, and increased costs for patients [49].

Conclusions

The present study provides a unique understanding of real-world evidence regarding the adherence and persistence to nusinersen for the treatment of SMA by utilizing different adherence criteria than other studies, which may be more reflective of real-world treatment patterns. The findings from this study suggest that adherence and persistence to nusinersen treatment are low, although claim-based studies might underestimate these parameters. Future research should confirm these results using other methodology and explore possible reasons for low adherence and persistence to nusinersen treatment, such as clinical or logistical factors, patient preferences, and payer restrictions.

References

Mercuri E, Bertini E, Iannaccone ST. Childhood spinal muscular atrophy: controversies and challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(5):443–52.

Farrar MA, Kiernan MC. The genetics of spinal muscular atrophy: progress and challenges. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12(2):290–302.

Verhaart IEC, et al. A multi-source approach to determine SMA incidence and research ready population. J Neurol. 2017;264(7):1465–73.

Lally C, et al. Indirect estimation of the prevalence of spinal muscular atrophy type I, II, and III in the United States. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):175.

Lefebvre S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80(1):155–65.

Lorson CL, et al. A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(11):6307–11.

Munsat T. Workshop report: international SMA collaboration. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991;1:81.

Munsat TL, Davies KE. International SMA consortium meeting (26–28 June 1992, Bonn, Germany). Neuromuscul Disord. 1992;2(5–6):423–8.

Tizzano EF, Finkel RS. Spinal muscular atrophy: a changing phenotype beyond the clinical trials. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(10):883–9.

Finkel RS, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(3):197–207.

Mercuri E, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(2):103–15.

European Medicines Agency. Spinraza. 2017 [06/11/20]; Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/spinraza.

Food and Drug Administration. SPINRAZA® (nusinersen) [package insert]. Cambridge: Biogen Inc.; 2016.

Biogen. SPINRAZA® (nusinersen) [package insert]. 2019 [cited 2022 September]; Available from: https://www.spinraza.com/PI.

Novartis. ZOLGENSMA® (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi) [package insert]. 2019 [cited 2022 September]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/126109/download.

European Medicines Agency. ZOLGENSMA® (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi). 2020 May [cited 2021 November]; Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zolgensma.

US Food and Drug Administration. EVRYSDI® Highlights of prescribing information. 2020 [cited 2022 September]; Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/213535s000lbl.pdf.

European Medicines Agency. EVRYSDI: Summary of Product Characteristics. 2021 [cited 2021 July]; Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/evrysdi-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

Ramdas S, Servais L. New treatments in spinal muscular atrophy: an overview of currently available data. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(3):307–15.

Mercuri E, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:625–35.

Burgart AM, et al. Ethical challenges confronted when providing nusinersen treatment for spinal muscular atrophy. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(2):188–92.

Michelson D, et al. Evidence in focus: Nusinersen use in spinal muscular atrophy: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;91(20):923–33.

Zingariello CD, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to dosing nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin Pract. 2019;9(5):424–32.

Elman L, et al. Real-world adherence to nusinersen in adults with spinal muscular atrophy in the US: a multi-site chart review study. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2022;9(5):655–60.

Gauthier-Loiselle M, et al. Nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy in the United States: findings from a retrospective claims database analysis. Adv Ther. 2021;38(12):5809–28.

IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus. 2020 [28/05/2020 25/01/2022]; Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/library/fact-sheets/iqvia-pharmetrics-plus.

Yong J, Moffett M, Lucas S. Implementing a global expanded access program (EAP) for infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy (type I): understanding the imperative impact and challenges. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2019;6(2):227–31.

Hache M, et al. Intrathecal injections in children with spinal muscular atrophy: nusinersen clinical trial experience. J Child Neurol. 2016;31(7):899–906.

Vrijens B, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691–705.

Coleman CI, Tangirala M, Evers T. Treatment persistence and discontinuation with rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0157769.

Vazquez-Costa JF, et al. Nusinersen in adult patients with 5q spinal muscular atrophy: a multicenter observational cohorts’ study. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(11):3337–46.

Lavie M, et al. Nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy type 1: real-world respiratory experience. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(1):291–8.

Hagenacker T, et al. Nusinersen in adults with 5q spinal muscular atrophy: a non-interventional, multicentre, observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(4):317–25.

Erdos J, Wild C. Mid- and long-term (at least 12 months) follow-up of patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) treated with nusinersen, onasemnogene abeparvovec, risdiplam or combination therapies: a systematic review of real-world study data. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2022;39:1–10.

Duong T, et al. Nusinersen treatment in adults with spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11(3):e317–27.

Gast A, Mathes T. Medication adherence influencing factors-an (updated) overview of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):112.

Biogen. CADTH common drug review: clinical review report. Nusinersen (Spinraza). 2018.

Verhaart IEC, et al. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q-linked spinal muscular atrophy—a literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):124.

Kolb SJ, Coffey CS, Yankey JW. Natural history of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Neurol. 2017;82(6):883–91.

Jalali A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of nusinersen and universal newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy. J Pediatr. 2020;227:274–80.

Chawa MS, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and patient perceptions on medication adherence in depression treatment. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22(6):20m02625.

Scheurer D, et al. Association between different types of social support and medication adherence. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(12):e461–7.

Lee H, et al. Combined effect of income and medication adherence on mortality in newly treated hypertension: nationwide study of 16 million person-years. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(16): e013148.

MacCannell D, et al. Population pharmacokinetics-based recommendations for a single delayed or missed dose of nusinersen. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021;31(4):310–8.

MacCannell D, et al. Restoration of nusinersen levels following treatment interruption in people with spinal muscular atrophy: simulations based on a population pharmacokinetic model. CNS Drugs. 2022;36(2):181–90.

Labianca L, Weinstein SL. Scoliosis and spinal muscular atrophy in the new world of medical therapy: providing lumbar access for intrathecal treatment in patients previously treated or undergoing spinal instrumentation and fusion. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2019;28(4):393–6.

Lo SH, et al. Preferences and utilities for treatment attributes in type 2 and non-ambulatory type 3 spinal muscular atrophy in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022;40(suppl 1):91–102.

Monette A, et al. Treatment preference among patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA): a discrete choice experiment. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:36.

Droege M, et al. Economic burden of spinal muscular atrophy in the United States: a contemporary assessment. J Med Econ. 2020;23(1):70–9.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study, including the journal’s Rapid Service and open access fees, was funded by Genentech Inc, South San Francisco, CA, USA.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Rosalind Carney, DPhil, of Nucleus Global. Editing assistance was provided by Jennifer Sollenberger of Nucleus Global. Support for this assistance was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Author Contributions

David Fox, Tu My To, Arpamas Seetasith, Anisha M. Patel, and Susan T. Iannaccone contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection, and writing. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

David Fox, Tu My To, Arpamas Seetasith, and Anisha M. Patel are employees of Genentech Inc and shareholders of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Susan T. Iannaccone has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, Muscular Dystrophy Association, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, Cure SMA, Department of Defense, AveXis, Biogen, PTC Therapeutics, Sarepta, FibroGen, Pfizer, and ScholarRock.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Our study used deidentified data and was exempt from the Institutional Review Board review. Our research was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Genentech has a data use agreement with PharMetrics Plus, which allows Genentech-associated researchers to use and analyze their data and to publish the corresponding results.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because our study used deidentified claims data that are proprietary to a third-party data vendor, and thus these data cannot be made available to readers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fox, D., To, T.M., Seetasith, A. et al. Adherence and Persistence to Nusinersen for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A US Claims-Based Analysis. Adv Ther 40, 903–919 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-022-02376-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-022-02376-y