Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to analyze the relationships between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment variables and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in Japanese patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and chronic low back pain (CLBP) using the data from a large-scale, real-world database.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed anonymized claims data from the Japanese Medical Data Center of medical insurance beneficiaries who were prescribed NSAIDs for OA and/or CLBP from 2009 to 2018.

Results

Of 180,371 patients, 89.3% received NSAIDs as first-line analgesics (oral, 90.3%; patch, 80.4%; other transdermal drugs, 24.0%). Incidence of AMI was 10.27 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval 9.20–11.34) in the entire study population. There was a trend towards increased risk in patients using NSAIDs for more than 5 years (P = 0.0784) than in those using NSAIDs for less than 1 year. Risk of AMI significantly increased with age and comorbidities of diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD). The risk for AMI was similar for patients who consistently used NSAIDs compared to those using them intermittently and patients who used patch compared to oral NSAIDs. Elderly patients used NSAIDs more consistently and used NSAID patches more frequently.

Conclusion

In Japanese patients with OA and CLBP, we saw a trend of increased risk for AMI in patients using NSAIDs for more than 5 years. Elderly patients had a higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and other CVD which increased the risk of AMI. Although NSAID patches were preferred to oral NSAIDs in elderly patients, risk for AMI was similar between the two modalities. Therefore, we suggest using NSAIDs carefully, especially in elderly patients and those at risk of developing CVD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and/or chronic low back pain (CLBP) require long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use. However, the side effects of long-term NSAIDs use limit its benefits in these patients. |

We aimed to assess health burden of cardiovascular events associated with NSAID use in Japanese patients with OA and/or CLBP. |

What was learned from the study? |

This retrospective database study shows that prolonged NSAID use increases risk of acute myocardial infarction. |

Elderly patients and patients with diabetes, hypertension, and other cardiovascular disease are at increased risk for acute myocardial infarction. |

Plain Language Summary

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used medications for relieving pain in patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and/or chronic low back pain (CLBP); however, their use is limited by some side effects. These side effects include abdominal, heart, and kidney dysfunction. This article describes a database study in Japanese patients with OA and CLBP that explored incidence of acute heart attack associated with NSAID use. Impact of NSAID treatment duration, mode of administration, and usage consistency on the risk of developing cardiovascular events was evaluated. The results suggest that NSAID treatment duration of more than 5 years affects the risk of acute heart attack, and age and comorbid diabetes, hypertension, and other cardiovascular disease significantly increase this risk. Meanwhile, elderly patients used NSAIDs more consistently and used patches more frequently. The authors of the study suggest that NSAIDs need to be used carefully, especially in elderly patients and those at risk of developing heart diseases.

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide and plain language summary, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13562708.

Introduction

Approximately one in three people worldwide live with a chronic and painful musculoskeletal condition caused by disorders of the bones, joints, muscles, tendons, ligaments, bursae, or their combination [1,2,3]. Osteoarthritis (OA) and chronic low back pain (CLBP) are the most common musculoskeletal conditions that significantly contribute to the global burden of years lived with disability [1, 4, 5]. Causes of low back pain are diverse and include herniated discs, disc degeneration, spondylotic changes, vertebral fractures and dislocations, osteoporosis, and psychological and social factors [6, 7]. In Japan, OA affects approximately 25.3 million individuals aged over 40 years and the prevalence of CLBP is estimated to be approximately 24.8% in individuals older than 50 years [8, 9]. Both OA and CLBP adversely impact healthy aging of individuals by limiting their physical and functional abilities; therefore, managing chronic pain is of the utmost importance, particularly in Japan where the median age of the population is 48.4 years, the highest in the world [10, 11].

Surgical therapy, non-pharmacological therapy (exercise, gait aids, cognitive behavioral therapy, and self-management programs), and pharmacological therapy are available management options for treating pain associated with OA and CLBP [12,13,14,15]. An analysis using data from hospital-based administrative databases showed that approximately 90% of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain were prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in Japan [16]. Transdermal NSAID patches have demonstrated a superior safety profile over oral NSAIDs, and are recommended as first-line treatment for knee and hip OA by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) guidelines [13, 14, 17,18,19]. NSAIDs are also commonly recommended and prescribed for CLBP in Japan.

NSAIDs exhibit anti-inflammatory action via inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX), COX-1 and COX-2 being the two major isoforms, which catalyze the production of prostanoids that sensitize the nociceptors and also mediate a variety of other biological effects [20]. Use of NSAIDs is associated with gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular (CV) safety events. Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown that NSAIDs increase the risk of developing acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, and hemorrhagic stroke [21,22,23]. Several studies point towards the increased CV risk being a class effect of NSAIDs and this is further supported by two meta-analyses showing that both COX-2-selective and nonselective NSAIDs increase the risk of CV adverse events by 30% and 42%, respectively [24, 25].

A meta-analysis showed that patients with OA are at 24% increased risk of developing CV disease compared to those without OA [26], and NSAIDs have been shown to contribute to this increase in CV risk in patients with OA [27]. Similarly, NSAID use has been found to be associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with CLBP [28]. Although the association between NSAID use and CV events is reported in controlled clinical studies, this association has not been thoroughly investigated in real-world settings in Japan, most likely because of the lower occurrence of CV events in the Japanese population (ca. 0.1–0.5%) [29]. However, since most Japanese patients with OA or CLBP use NSAIDs for pain relief, estimating the incidence of CV events and the impact of NSAID use in these patients is of significant clinical relevance [29]. Accordingly, we set out to determine the association between the incidence of CV events and different NSAID treatment variables like treatment duration, mode of administration, and usage consistency in Japanese patients with OA and CLBP using a large administrative database. For CV events, we examined AMI, which is often examined for the association between NSAIDs and CV risk [30].

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

This was a retrospective, longitudinal, observational cohort study, using claims from the Japan Medical Data Center (JMDC). JMDC is the largest claims database commercially available in Japan that records all claims across multiple medical institutions and can also track patients who have changed medical institutions. The database contains claims data from approximately 7.2 million inpatients and outpatients, and pharmacy claims from medical institutions made by Japanese health insurance companies for employees and their family members who are at most 75 years old. JMDC contains anonymized information about diagnoses, patient characteristics, drug prescriptions, medical procedures, features of medical facilities, and reimbursement costs. All patient data are encrypted before entry. Diseases are coded according to Japanese Claims Codes and the coding scheme of the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10).

For this study, eligible patients were aged at least 18 years at the index date, with an initial ICD-10 diagnosis of OA (ICD-10 codes M16 and M17) or CLBP (at least two ICD-10 low back pain diagnoses [M40, M41, M43, M45–M48, and M50–M54] at least 1 month apart within the previous 3 months), and with evidence of visiting healthcare facilities in the administrative databases between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2018. Patients with comorbidity of malignancy (ICD10 codes C00–C97, D00–D09) after the initial diagnosis of OA or CLBP were excluded. Moreover, patients diagnosed with CLBP but having other diagnoses like neck pain, radiculopathy and myelopathy, infection, vascular disease, acute low back pain, and limb symptoms were excluded from this analysis (detailed ICD codes are described in Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material). The index date was defined as the date when the first prescription of analgesic was given after initial diagnosis of OA or CLBP. Those patients taking two or more prescriptions of the same or different analgesic with at least a 1-month gap after initial OA/CLBP diagnosis, and 6 months of baseline period with no prescriptions for analgesic were also included. As this study involved anonymized structured data, no informed consent was sought from patients. The study is reported in compliance with the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement [31].

Exposure

Series of treatment consisted of single or multiple treatment periods per the prescription with the same class of pain drugs and up to a 3-month gap between the initial date of the prescription and the end date of the previous prescription. Exposure period was defined as a combination of series of NSAID treatment plus 3 months that ended the day when the first CV event occurred. The NSAID treatment variables were duration of treatment, mode of administration (oral drugs, patch, other transdermal drugs), and consistency of NSAID use. Categories of treatment duration were > 0 to 1 year, > 1 to ≤ 3 years, > 3 to ≤ 5 years, and > 5 years. Consistent NSAID use was defined as a percentage of the number of supply days in the total treatment duration of at least 70%, and intermittent use was identified as a percentage of the number of supply days in a total treatment duration of less than 70%.

Study Outcomes

The incidence of CV events was assessed. CV events were defined as the occurrence of AMI at any time during exposure period and their diagnostic codes are presented in Table S2 in the electronic supplementary material. Since other CV diseases such as angina and heart failure are commonly recorded in elderly patients in the claims data for tests and prescriptions, those were excluded from the definition of CV events in this study to estimate a more accurate incidence.

Statistical Analysis

All patients who met the eligibility criteria were included in the analysis set. Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics or frequencies with percentages for dichotomous and polychotomous variables of categorical data. The crude incidence (per 10,000 person-years) for AMI and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. The incidence rate was calculated as the number of patients who experienced AMI divided by the total exposure period. We also performed a subgroup analysis for patients aged less than 65 years and patients aged 65 years or more. The effect of treatment regimen of NSAIDs on the risk of AMI using risk ratios was evaluated by an overdispersed Poisson regression model using the SAS GLIMMIX procedure with the log link function and the logarithm of the exposure period as an offset. Covariates included age, gender, baseline comorbidities, and preventive drugs that were prescribed. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). An alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics Statement

As this study involved anonymized structured data, which according to applicable legal requirements did not contain data subject to privacy laws, obtaining informed consent from patients was not required. As Japanese ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects [32] do not apply to studies that use anonymized secondary data, this study was not reviewed by any institutional review board/research ethics committee.

Results

Patient Disposition

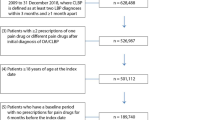

Between January 2009 and December 2018, 628,488 patients in the JMDC database were diagnosed with OA and/or CLBP, of which 526,987 were prescribed one or more analgesics at least twice. After exclusion of patients aged less than 18 years and those with prescription of analgesic within 6 months of index date or those with malignancy, 180,371 patients were included in the analysis. Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and NSAID use are described in Table 1. A total of 32.9% patients had OA, 53.8% had CLBP, and 13.4% had both OA and CLBP. Prevalence of comorbid GI disease was 7.9%; renal disease, 0.8%; hypertension, 21.9%; other CV disease, 13.4%; and diabetes 11.8%. Patients aged 65 years or more (N = 14,433) were predominantly female (54.5% vs. 48.1%), had a higher prevalence of diabetes (26.6% vs. 10.5%), hypertension (49.1% vs. 19.5%), and other CV disease (32.4% vs. 11.8%) compared to those aged less than 65 years. Patient characteristics remained similar across OA and CLBP subgroups (Table S3 in the electronic supplementary material).

First-Line NSAID Use

NSAIDs were administered as first-line analgesics to 161,152 (89.3%) patients. Oral NSAIDs were used in 90.3% of patients, patch NSAIDs in 80.4%, and other transdermal drugs (cream, gel, liquid, lotion, ointment) in 24.0%. The proportion of patients using a combination of oral and topical (patches, other transdermal, and suppository) NSAIDs was 88.6%. Oral NSAIDs were used in combination with patch NSAIDs in 65.1% of patients, and in combination with other transdermal NSAIDs in 14.5%. Overall, 83.7% of patients had been using NSAIDs for up to 1 year. Consistent use of NSAIDs was reported in 21% of patients and the use of patch NSAIDs was more consistent than oral NSAIDs in each stratum of the treatment duration (Table 2). Irrespective of the mode of administration, NSAIDs were used more consistently in patients aged 65 years or more than in those aged less than 65 years (31.3% vs. 20.1%). Moreover, NSAID patches were used more frequently (86.6% vs. 79.9%) in patients aged 65 years or more than in those aged less than 65 years (Table 1).

Cardiovascular Events

The overall incidence rate of AMI was 10.27 per 10,000 person-years (95% CI 9.20, 11.34) (Table 3). The risk of AMI in patients using NSAIDs for more than 5 years was nearly twice compared to those using NSAIDs for less than 1 year (risk ratio [RR] 1.92, 95% CI 1.05, 3.52; P = 0.0346). The incidence of AMI was similar in patients who used NSAIDs consistently compared to those who did not (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.85, 1.62; P = 0.3257) and in those who used patch NSAIDs compared to oral (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.67, 2.14; P = 0.5347) (Table 4). When all three variables of NSAIDs were included in the model, none was statistically non-significant (e.g., P = 0.078 for use for more than 5 years) (Table 5). On the contrary, the majority of patient-related factors were found to increase the risk of AMI: the incidence of AMI was higher in patients aged 65 years or more than in those aged less than 65 years (20.97 [95% CI 15.04, 26.91] vs. 9.51 [8.45, 10.58]). The association was found to be statistically significant in model analysis and the risk was 4- to 16-fold higher in patients aged at least 40 years compared to those aged less than 40 years (Table 5). The risk of developing AMI was estimated to be 56% higher in patients with hypertension compared to those without in model analysis (RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.09, 2.23; P = 0.0156). Similarly, the risk was higher in patients with baseline CV comorbidities, albeit excluding hypertension (RR 2.78, 95% CI 2.07, 3.73; P < 0.0001) and in patients with diabetes compared to patients without (RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.18, 2.48; P = 0.0049). Per model analysis, the risk of developing AMI was higher in men (RR 2.96, 95% CI 2.31, 3.78; P < 0.0001). The pattern of CV events was similar in patients with OA and patients with CLBP (Table S4 in the electronic supplementary material). Overall, in the model analysis, among patient-related factors, the relative risk was higher for age compared to other factors, indicating older age to be a significant contributor to increase in the risk of AMI (Table 5).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first real-world study reporting the incidence of AMI in patients treated with NSAIDs using data from a large administrative database in Japan. There was a trend towards increasing risk of AMI in patients using NSAIDs for more than 5 years compared with those using for less than 1 year. The incidence of AMI was numerically higher in patients using NSAIDs consistently compared to those receiving them intermittently; however, this increase in risk was not statistically significant. Among the patient-related factors, age exerted a very large effect on the risk of developing AMI. Male gender and comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, and other CV disease were found to increase the incidence of AMI.

The incidence of AMI reported in our study is in line with prior studies. The incidence of MI was 26/10,000 person-years in patients using ibuprofen in a study by Patel et al. [33]. In a 3-year nationwide observational study in Japan, the incidence of CV events including MI, angina pectoris, heart failure, cerebral infarction, and cerebral hemorrhage was 6.8/1000 person-years and the incidence of MI alone was 0.4/1000 person-years in patients with OA and rheumatoid arthritis with the use of NSAIDs [29]. It was estimated that of 1000 patients who receive NSAIDs for 3 years, one will have a fatal vascular event; when 1000 high-risk patients are treated with NSAIDs for 1 year, seven or eight will experience a major vascular event, of which two events could be fatal [34]. Moreover, patients with OA and CLBP are known to exhibit elevated CV risk [26,27,28]. Therefore, OA and CLBP management guidelines recommend that oral NSAIDs should be used intermittently [18, 35].

Comorbidities of diabetes, hypertension, and other CV disease significantly increased the risk of AMI in our study. Evidence shows that patients with preexisting CV disease such as hypertension, AMI, heart failure, and history of stroke have greater risk of developing CV events when treated with NSAIDs [36,37,38,39,40]. Among the patient-related factors that increased the risk of AMI in our study, age had the highest risk ratio indicating it to be an important factor mediating CV risk of NSAIDs. As pain is common in the elderly population, and OA and CLBP affect two-thirds of this group, these patients are more likely to use NSAIDs, but they may not be aware of avoiding NSAIDs if they have pre-existing CV disease [41]. Therefore, in patients with CV comorbidities, use of any oral NSAID is not recommended by OARSI guidelines [18]. This is in line with the evidence that shows age as an independent predictor of CV disease including MI [42, 43]. A clear trend for higher prevalence of OA and CLBP with increasing age has been shown in several systematic reviews and meta-analyses [44,45,46].

Risk of AMI in patients using NSAIDs for more than 5 years was significantly larger (P = 0.035) compared with those using for less than 1 year but the significance was lost (P = 0.078) when all three NSAIDs treatment factors were adjusted for. Thus, these results may not be conclusive for the effect of NSAID treatment duration on AMI risk because of confounding but they do appear to indicate the trend. The plausible reasons for the unclear association could be a much higher impact of age and comorbidities on CV risk and a relatively longer time to develop AMI [47]. Further studies with longer duration of NSAID use, such as more than 10 years, would better substantiate the results. In addition, there may be other confounding factors such as severity of OA; however, such information is not available in the claims database. In this study, elderly patients used NSAIDs consistently and used NSAID patches more frequently than oral NSAIDs. Simple subgroup analysis showed higher AMI risk in patients consistently using NSAIDs despite no clear association observed in the multivariate analysis that could be confounded by age. Understandably, since patients with OA and CLBP are high-risk elderly patients who consistently use NSAIDs over the long term and prefer patches to oral, their NSAID prescriptions should be monitored carefully. Indeed, in patients who are at high risk of CV events, consistent use of NSAIDs should be avoided. Although NSAID patches are considered safer than oral/systemic use of NSAIDs, the risk of AMI was similar in patients using patch or oral NSAIDs in our study. Given that NSAID patches tend to be used more consistently, care should be taken even when using this form of treatment.

The major strength of the present study is the use of data from a large administrative claims database that allows estimation of events that have a low occurrence rate. In the absence of medical chart information, unavailability of data for the elderly (over 65 years of age), and the severity of disease, and confounding by other factors such as alcohol consumption and smoking in the model analysis were limitations that might lead to bias in estimating the association between risk of AMI and NSAID exposure, and thus would not permit generalization of data for all patients with OA and CLBP. The claims database used in this study does not capture information of patient deaths and is thereby another important limitation. The choice of cutoff for NSAID treatment duration and the definition of consistent use could be a potential bias in interpreting the results.

Conclusion

In this real-world study of a Japanese population, we could see a trend towards increased risk for AMI in patients treated with any NSAID formulation for more than 5 years. No clear association between consistent use of NSAIDs and the risk of AMI was observed. Elderly patients with OA and CLBP using NSAIDs have a higher prevalence of comorbidities of diabetes, hypertension, and other CV disease which increases the risk of AMI. Although there was a preference for NSAID patches to oral NSAIDs owing to better safety, our results showed that the risk for AMI is similar between the two modalities. The use of NSAIDs is more consistent in elderly patients. Thus, we suggest NSAIDs need to be used carefully, especially in elderly patients and those at risk of developing CV disease.

References

Briggs AM, Woolf AD, Dreinhöfer K, et al. Reducing the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(5):366.

Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain. 2008;9(10):883–91.

International Association for the Study of Pain. Musculoskeletal pain fact sheets. https://www.iasp-pain.org/Advocacy/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1101. Assessed 01 Dec 2020.

WHO. Musculoskeletal conditions. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions. Assessed 02 Nov 2020.

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–96.

Urits I, Burshtein A, Sharma M, et al. Low back pain, a comprehensive review: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(3):23.

Nijs J, Apeldoorn A, Hallegraeff H, et al. Low back pain: guidelines for the clinical classification of predominant neuropathic, nociceptive, or central sensitization pain. Pain Phys. 2015;18(3):E333–46.

Yoshimura N. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis in Japan: the ROAD study. Clin Calcium. 2011;21(6):821–5.

Iizuka Y, Iizuka H, Mieda T, et al. Prevalence of chronic nonspecific low back pain and its associated factors among middle-aged and elderly people: an analysis based on data from a musculoskeletal examination in Japan. Asian Spine J. 2017;11(6):989.

Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Schneider CH, Hoy DG, March LM. The global burden of musculoskeletal pain—where to from here? Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):35–40.

Kojima G, Iliffe S, Taniguchi Y, Shimada H, Rakugi H, Walters K. Prevalence of frailty in Japan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol. 2017;27(8):347–53.

Ebata-Kogure N, Murakami A, Nozawa K, et al. Treatment and healthcare cost among patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study using a real-world claims database in Japan between 2013 and 2019. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40(11):1071–84.

The Japanese Orthopaedic Association. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines adapted to Japanese by Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) Committee on clinical practice guideline on the management of osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Research Society International 2012.

Japanese Orthopaedic Association. Clinical practice guideline on the management of osteoarthritis of the hip. 2nd ed. Tokyo: Nankodo; 2016.

Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Use and costs of prescription medications and alternative treatments in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in community-based settings. Pain Pract. 2012;12(7):550–60.

Akazawa M, Mimura W, Togo K, et al. Patterns of drug treatment in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in Japan: a retrospective database study. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1631.

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based. Expert Consens Guidel Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16(2):137–62.

Bannuru RR, Osani M, Vaysbrot E, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(11):1578–89.

Association TJO. Clinical practice guideline on the management of low back pain. 2nd ed. Tokyo: Nankodo; 2019.

Schmidt M, Lamberts M, Olsen A-MS, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: review and position paper by the working group for Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(13):1015–23.

Bally M, Dendukuri N, Rich B, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction with NSAIDs in real world use: Bayesian meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ. 2017;357:j1909.

Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Thongprayoon C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of incident heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(2):111–8.

Ungprasert P, Matteson EL, Thongprayoon C. Nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of hemorrhagic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Stroke. 2016;47(2):356–64.

Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emberson JR, Patrono C. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332(7553):1302–8.

Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7086.

Wang H, Bai J, He B, Hu X, Liu D. Osteoarthritis and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39672.

Atiquzzaman M, Karim ME, Kopec J, Wong H, Anis AH. Role of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in the association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular diseases: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(11):1835–43.

Wang H-C, Su Y-C, Luk H-N, Wang J-H, Hsu C-Y, Lin S-Z. Increased risk of strokes in patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP): a nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;192:105725.

Hirayama A, Tanahashi N, Daida H, et al. Assessing the cardiovascular risk between celecoxib and nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Circ J. 2014;78(1):194–205.

Varas-Lorenzo C, Riera-Guardia N, Calingaert B, et al. Myocardial infarction and individual nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(6):559–70.

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2016;115:33–48.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Japan and Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects. 2018. https://www.lifescience.mext.go.jp/files/pdf/n2181_01.pdf. Assessed 10 Dec 2020.

Patel TN, Goldberg KC. Use of aspirin and ibuprofen compared with aspirin alone and the risk of myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(8):852–6.

Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al. Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769–79.

Bruyère O, Cooper C, Pelletier J-P, Maheu E, Rannou F, Branco J, et al., editors. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis—from evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;45:S3-S11.

Olsen A-MS, Gislason GH, McGettigan P, et al. Association of NSAID use with risk of bleeding and cardiovascular events in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2015;313(8):805–14.

Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):141–9.

Kohli P, Steg PG, Cannon CP, et al. NSAID use and association with cardiovascular outcomes in outpatients with stable atherothrombotic disease. Am J Med. 2014;127(1):53–60.

Ray WA, Varas-Lorenzo C, Chung CP, et al. Cardiovascular risks of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in patients after hospitalization for serious coronary heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(3):155–63.

Schjerning Olsen A-M, Fosbøl EL, Lindhardsen J, et al. Duration of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and impact on risk of death and recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with prior myocardial infarction: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2226–35.

McCarberg BH. NSAIDs in the older patient: balancing benefits and harms. Pain Med. 2013;14(suppl_1):S43–4.

Rodgers JL, Jones J, Bolleddu SI, et al. Cardiovascular risks associated with gender and aging. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2019;6(2):19.

Garoufalis S, Kouvaras G, Vitsias G, et al. Comparison of angiographic findings, risk factors, and long term follow-up between young and old patients with a history of myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 1998;67(1):75–80.

Dagenais S, Garbedian S, Wai EK. Systematic review of the prevalence of radiographic primary hip osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(3):623.

Loeser RF. Aging and osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(5):492.

Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Faria NMX. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49:73.

Gidding SS, Sood E. Preventing cardiovascular disease: going beyond conventional risk assessment. Circulation. 2015;131(3):230–1.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The study and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fee were sponsored by Pfizer Japan Inc.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Editorial and/or medical writing support were provided by MedPro Clinical Research (Haruyoshi Ogata), supported by CBCC Global Research (Leena Patel and Sonali Dalwadi), and was funded by Pfizer Japan Inc. Data analytics support was provided by the Institute of Japanese Union of Scientists & Engineers (Kazuhiko Hase and Yasushi Shimoda), who were paid contractors to Pfizer Japan Inc. in the development of this manuscript.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Kanae Togo, Nozomi Ebata, Koichi Fujii, and Naohiro Yonemoto are employees of Pfizer Japan Inc. and shareholders of Pfizer Inc. Lucy Abraham is an employee and shareholder of Pfizer Ltd. Shogo Kikuchi and Takayuki Katsuno have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

As this study involved anonymized structured data, which according to applicable legal requirements did not contain data subject to privacy laws, obtaining informed consent from patients was not required. The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements described in guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) issued by the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology, Good Practices for Outcomes Research issued by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR). The study is reported in compliance with the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as all the rights for database ownership are reserved with the JMDC Inc. However, Pfizer Inc. has a contract with JMDC to use this database and publish the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kikuchi, S., Togo, K., Ebata, N. et al. Database Analysis on the Relationships Between Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Treatment Variables and Incidence of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Japanese Patients with Osteoarthritis and Chronic Low Back Pain. Adv Ther 38, 1601–1613 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01629-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01629-6