Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to evaluate the dimensions of the vaginal canal in patients undergoing gynaecological brachytherapy and the effect of the use of vaginal dilators (VD) used in the follow-up of pelvic physiotherapy.

Methods

A total of 88 patients were randomly allocated to the control group (CG) and intervention group (IG). Three evaluations were performed: pre-brachytherapy, post-brachytherapy and follow-up of 3 months. The CG received standard guidance from the health team while the IG was instructed to use VD for 3 months. The dimensions of the vaginal canal (main outcome) were defined by the length of the vagina (centimetres), width (number of full clockwise turns of the opening thread of a gynaecological speculum) and area (defined by the size of the VD). Quality of life and pelvic floor (PF) functionality were also evaluated.

Results

There was no effect of the VD on vaginal length, width and area among the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. However, in the analysis stratified by adhesion, the CG had a significant decrease in the vaginal area. PF was predominantly hypoactive throughout the follow-up. Quality of life improved in both groups, but the reduction of constipation, vaginal dryness and stress urinary incontinence manifested only in the IG.

Conclusion

The use of VD did not alter the dimensions of the vaginal canal within the first 3 months after the end of radiotherapy treatment. However, there was a large sample loss during follow-up so studies with a larger sample number and longer follow-up time need to be conducted.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03090217.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the seventh most common cancer in the world, especially in regions with a low human development index where it is associated with 7.5% of cancer deaths [1]. The treatment of advanced cancer varies according to the degree of the disease staging and consists of the application of external irradiation to the pelvis and/or intracavitary and neoadjuvant chemotherapy [2]. More specifically, women with cervical cancer experience emotional problems prior to therapy and lymphoedema, and urological and sexual problems following treatment [3, 4]. These treatment-related complications and sexual dysfunction significantly affect patients’ quality of life (QoL) [5,6,7].

Radiotherapy involves two techniques of application, an external and intracavitary way, and has been considered fundamental to the increase in rates of recurrence-free survival [8,9,10]. However, the use of ionizing radiation induces difficult-to-resolve adverse effects that may adversely interfere with treatment [11]. The adverse effects of the radiotherapy treatment can start early in the first applications and extend for years. Acute effects are all clinical manifestations that occur within the first 3 months after treatment [12, 13], the most frequent of which are gastrointestinal and genitourinary [13]. In addition, the radiation causes damage to the vaginal epithelium, which may reduce tissue vascularization leading to pallor of the vaginal mucosa, loss of lubrication and inflammation [9, 14,15,16].

This inflammatory process is associated with posterior fibrosis of muscle fibres and mucosal atrophy [9], which may result in narrowing of the vaginal canal [17,18,19]. According to Hofsjö et al. a morphological change occurs, causing the elastic fibres to be distributed dysfunctionally and with high density of collagen [20]. These effects are intensified with the use of brachytherapy where larger doses are locally applied [21]. Often, in these clinical situations, there is narrowing of the vaginal canal that prevents the continuation of treatment by brachytherapy, gynaecological examinations and maintenance of sexual activity [21].

The variation in the dimensions of the vaginal canal leads to different degrees of vaginal stenosis [2]. Aiming to minimize the effects that the radiotherapy treatment promotes on the vaginal dimensions, vaginal dilators [22,23,24,25] have been widely used [2, 24]. However, their use is limited by psychological resistance [16] and the reasons why women are reluctant to engage in rehabilitative dilator use have not been fully investigated. This resistance may be related to several factors such as embarrassment, anxiety, modesty, pain, fear of damaging the vagina, feeling unskilled at putting an object inside one’s own vagina and insufficient information about dilator use [26]. In addition, there is still a lack of evidence demonstrating the benefits of using this technique on vaginal dimensions, pelvic floor (PF) functionality, clinical signs and symptoms, and QoL [16, 27]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of the use of vaginal dilators (VD) on the vaginal canal dimensions of patients undergoing gynaecological brachytherapy. As secondary endpoints, the effect of VD on PF functionality, clinical signs and symptoms and quality of life was evaluated.

Methods

This was a single-centre randomized clinical trial involving 88 women with cervical cancer and assigned to radiotherapy whose vaginal dimensions after usage of VDs were evaluated from January 2017 and May 2018. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia in Porto Alegre (CAAE: 63083516.4.0000.5335) and duly registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03090217).

All procedures involving human participants performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia in Porto Alegre (CAAE: 63083516.4.0000.5335) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

All patients were invited to participate in the study; at the end of radiotherapy treatment by teletherapy, they were referred to the intracavitary irradiation sessions of gynaecological brachytherapy. To participate in the study, the dimensions of the vaginal canal at the initial pre-brachytherapy evaluation should be considered normal (mean vaginal length of 9.6 cm with a wide range varying from 6.5 to 12.5 cm) [28] and the patient must not have undergone previous brachytherapy, been diagnosed with cervical cancer, be free of hysterectomy and aged over 18 years old. Patients with complications that impeded the protocol, such as severe bleeding, or those who did not complete the treatment with gynaecological brachytherapy were dismissed. All study phases were designed and reported in accordance with the CONSORT statement and are displayed in Fig. 1.

Assessments

A trained physiotherapist evaluated the volunteers at three times: (1) before the first brachytherapy session, (2) at the last brachytherapy session and (3) at 3 months after the end of treatment (Fig. 2). Clinical and sociodemographic evaluation was initially performed, followed by determination of vaginal canal dimensions, PF examination and quality of life. The determination of vaginal canal size included evaluation of length, width and area. The vaginal length (centimetres) was determined using a hysterometer, using the posterior fornix of the vagina as the starting point, and the hymenal ring as the end point. The width of the vagina was measured using vaginal dilators (VDs). Different graduations of Sós VDs (MDTi Company Ltd., UK) were used. For this, different VDs were inserted, in ascending order of size. The size setting should result from the largest VD capable of being inserted and maintained without pain, tightening or bleeding for at least 3 min. The measurements of the height and width of the VD, according to the values indicated by the manufacturer of the device, were used to calculate the area of the vagina (square centimetres). Measurement of the width of the vagina was determined through the opening of the vaginal speculum. To do this, in the horizontal position, a number one acrylic speculum was introduced into the vagina. During the opening of the speculum, each clockwise half-turn given on the thread was registered. The total number of half-turns was used as the width measurement parameter. The opening of the speculum was limited by mechanical restriction or by the manifestation of pain. Kinesiological-functional diagnosis of the pelvic floor (KFD-PF) was performed through bidigital palpation. Endurance and power of this musculature was determined as proposed by Bernards et al. [29]. The classification of the activity of this musculature followed the recommendations proposed by Messelink et al. [30] and were stratified into (1) hypoactive (inability to contract PF muscle voluntarily and involuntarily when necessary), (2) normal (ability of PF muscles to undergo normal or strong voluntary contraction and complete voluntary relaxation, in addition to pre-contraction present) and (3) hyperactive (PF muscles do not relax, or may even contract when relaxation is functionally needed); QoL was assessed by the Quality of Life Assessment questionnaire of the general neoplasia patient proposed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30) [31].

Allocation and Masking

The volunteers eligible to participate in the study were randomly assigned from a random list generated in the software package random (https://www.random.org) to the control group (CG) or intervention group (IG) in a ratio of 1:2, respectively. Given the nature of the procedure, neither the participants nor the clinicians were masked to group assignment. In the CG, the volunteers received only the usual guidance from the nursing team and participated in all the evaluations foreseen in the study. In the IG, the volunteers received the VD and all necessary guidelines for its use. The VD size was defined at the initial evaluation and each volunteer received the device with the size compatible with the individual anatomical conditions. The early initiation of the use of VD, i.e. concomitantly with brachytherapy, was evaluated in a subgroup of volunteers. However, the statistical analysis showed that the early use of these VDs did not promote any difference in the vaginal dimensions and therefore the IG was composed of volunteers who used the VD at the beginning of the brachytherapy (n = 23) and volunteers who only started after the end of the brachytherapy (n = 34). Thus, the allocation ratio resulted in one volunteer in the CG for every two in the IG.

Power Analysis

In order to calculate the sample size, we used the data published in the study by Kirchheiner et al. [21], which evaluated the incidence rate of vaginal stenosis of 630 women with advanced uterine cancer treated with brachytherapy. In this study, there was a clinically significant alteration in vaginal dimensions in 17% of the cases. On the other hand, the effect of the use of VD, published by Law et al. [32], reduced the vaginal canal volume in 109 of women treated with gynaecological brachytherapy by 73%. On the basis of these studies, the calculation of the sample size considered a 17% alteration in the dimensions of the vaginal canal and reduction of these alterations in 73% of the treated cases. At a significance level of 1% and power of the hypothesis test of 80%, the estimated sample size was 85 volunteers.

Treatment

Radiotherapy treatment was determined by the care routine that takes into account the patient’s clinical peculiarities and the degree of tumour staging. The minimum radiation dose used was 45 Gy and the maximum dose was 50.4 Gy, divided into 25–28 fractions (sessions) of 1.8 Gy. The sessions were conducted daily by teletherapy. At the end of the teletherapy, the volunteers were referred to the intracavitary irradiation sessions by gynaecological brachytherapy, performed according to the protocol of the radiotherapy service (from a Center of High Complexity of the South of Brazil—CACON) using GammaMedplus™ iX HDR/PDR Brachytherapy Afterloader with iridium-192, guided by X-ray image. The dose used was 7 Gy divided into four fractions applied once a week, applied through rings and/or cylinders. It was recommended to abstain from sexual activities after the beginning of brachytherapy until the fourth week of the end of the intracavitary irradiation. The use of VDs was individual, and the patients were oriented to use the device for 3 months, four times a week and for 10–15 min each time. The VDs were given to the patients following the stipulation of vaginal size on the first evaluation. The beginning of the VD use was divided into two moments: (1) concomitant with brachytherapy, (2) 4 weeks after the end of brachytherapy. However, in the stratified analysis there was no difference between the different moments and for this reason the data were treated in a grouped manner. In addition, PF muscle training was excluded from the original protocol, previously registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. The simplification of the original protocol was aimed at strengthening the investigation regarding the early use of VD in the prevention of changes in the dimensions of the vaginal canal.

Statistical Methods

An independent investigator, without previous knowledge of the groups, performed all the statistical analysis. The qualitative data were presented as frequency and percentage, whereas the quantitative data were presented as mean, median, standard deviation, standard error and interquartile range, according to the normal distribution of the values. Normality was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Comparisons between groups were performed using Student’s t test or the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. Associations were found by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, while correlations were identified by Spearman’s correlation test. Comparisons between moments and between groups were evaluated using generalized estimation equation (GEE) models with Bonferroni post hoc tests according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) method. The statistical significance in use was 5% (p < 0.05) and the analyses were done in SPSS software version 23.

Results

A total of 101 patients were evaluated for eligibility. Of these, 12 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or because they did not agree to participate in the study. The sample consisted of 88 women (43.7 ± 11.9 years) randomized to the CG (n = 32) and IG (n = 56). During the follow-up, there was loss due to death, withdrawal and need for hospitalization (Fig. 1). Clinical variables were symmetrically distributed between groups, except for the therapeutic regimen used in the pre-brachytherapy period, and are displayed in Table 1.

The frequency of conization was higher in the CG when compared to the IG. Adherence to the protocol declined with follow-up and there was a high rate of loss throughout the study but this behaviour was similar between the groups (X2 = 0.146, p = 0.702). The results of multivariate analyses showed that adherence was not significantly influenced by the variables (Table 1). However, in women with hypoactive PF, there was a tendency for less adherence to follow-up (p = 0.070). Dimensions of the vaginal canal, reported as length (in centimetres), width (number of turns of the gynaecological speculum) and area (in square centimetres), and the KFD-PF evaluations before, after brachytherapy and at the end of follow-up period are reported in Table 2. In the multivariate analysis no intervention effect was observed for any of the vaginal canal size variables on the ITT population (length: F = 2.545, p = 0.111; width: F = 0.490, p = 0.484; area: F = 0.107, p = 0.743). When stratifying the results of the volunteers who participated in all the proposed evaluations (CG: n = 9 and IG: n = 17), we did not find an effect of the use of dilators on vaginal length and width (F = 0.206, p = 0.614; F = 0.917, p = 0.348). However, in the CG there was a significant reduction in the vaginal area at the end of the segment (p = 0.046).

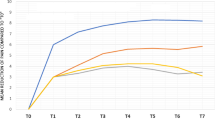

There was also no interaction between intervention and time for the variables width and area (width: F = 1.135, p = 0.567; area: F = 3.228, p = 0.199). However, there was interaction between intervention and time in the variable length (F = 6.286, p = 0.043), in which the basal vaginal length values were lower in the CG (6.6 ± 0.19 cm vs 7.3 ± 0.16 cm, p = 0.011). This difference remains in the post-brachytherapy evaluation (CG: 6.6 ± 0.22 cm; IG: 7.3 ± 0.17 cm; p = 0.003), but it reduces at the end of follow-up (CG: 7.2 ± 0.29 cm, IG: 6.9 ± 0.26 cm, p = 0.377) as shown in Fig. 3. In the analysis where conization was treated as covariate, the results were maintained, demonstrating that, independently of clinical conditions, the treatment did not significantly alter vaginal dimensions. The same was observed when we tested the influence of signs and symptoms related to the treatment of gynaecological cancer.

The KFD-PF result was similar between the groups at baseline assessment (baseline CG: 59.4% hypoactive, 12.5% hyperactive, 28.1% normal; IG: 69.6% hypoactive, 14.3% hyperactive, 16.1% normal) and there was no significant alteration of the diagnoses during follow-up (X2 = 3.119, p = 0.210) (Table 2).

Prevalence and incidence were similar between groups for most of the clinical findings, and there were no effects of treatment (X2 = 1.909, p = 0.167) and time (X2 = 0.548, p = 0.760) on the number. However, when we analysed the clinical occurrences only in the women who completed all the evaluations foreseen in the protocol, we identified that in the IG there was a significant reduction in constipation and vaginal dryness at the end of follow-up. A relevant fact is that in the stratified analyses, stress urinary incontinence (SUI) remained lower in the IG as described in Table 3.

The overall quality of life assessment score was similar between the groups throughout the follow-up (X2 = 0.007, p = 0.936). Likewise, domains that evaluated aspects related to functional quality and clinical symptoms were similar between groups (X2 = 0.001, p = 0.973; X2 = 0.152, p = 0.666, respectively); all domains improved at the end of follow-up (global domain: X2 = 5.995, p = 0.05; functional domain: X2 = 24,767, p = 0.001; symptoms domain: X2 = 17,077, p = 0.001), as described in Table 4. Only in the functional domain was the effect of time significant in isolated intragroup analyses.

The results demonstrated that there were no associations between the KFD-PF and the length and area of the vaginal canal. On the other hand, women with hypoactive PF had a significant decrease in vaginal width (p = 0.042). Regarding QoL (QLQ-C30), significant improvement in the overall health domain was observed throughout the follow-up and occurred independently of the KFD-PF. However, women with hyperactive PF presented significant improvement in quality of life (p = 0.006), whereas in the symptom domain there was a significant worsening in the cases of PF hypoactivity (p = 0.006). In the analysis stratified by adherence, the association between KFD-PF and the QLQ-C30 domains was also similar to those observed in the statistical treatment of intention to treat. The total number of occurrences of clinical signs and symptoms did not influence the quality of life. However, in the isolated or combined presence of vaginal discharge, urinary retention, diarrhoea and oedema, there was a lower score in the functional domain (X2 = 3.842, p = 0.050; X2 = 7.839, p = 0.005; X2 = 3.766, p = 0.05; X2 = 4.731, p = 0.30, respectively).

Vaginal dryness and constipation negatively influenced the symptoms domain (X2 = 5.597, p < 0.18; X2 = 8.032, p = 0.005, respectively). There was also a negative association between constipation and overall quality of life (X2 = 6.027, p = 0.049).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to evaluate the behaviour of the vaginal canal dimensions during the first 3 months after the end of the radiotherapy followed by gynaecological brachytherapy to determine the possible benefits of the use of vaginal dilators that have been used in the monitoring of pelvic physiotherapy. At the end of the follow-up, we observed that there was no difference between the intervention and control groups in relation to the variables used in the determination of vaginal dimensions, as well as no effect of the intervention on quality of life, signs and symptoms, and KFD-PF.

The random formation of the groups guaranteed similarity in the clinical conditions between the groups, but there was a significant difference in relation to the therapeutic scheme used in cancer treatment. The prevalence of conization was higher in the control group, but in the stratified analysis this condition did not significantly interfere with the dimensions of the vaginal canal. Adherence to the protocol was considerably low and declined with follow-up in both groups. Only 28% of the women performed the final evaluations in the CG and 30% in the IG. This difficulty of adherence is reported by different health professionals who handle women with cervical cancer [33, 34]. We did not identify any predictive factors for these losses, but adherence tended to be lower in women with PF hypoactivity, corroborating the findings of Rutledge [35] who obtained greater agreement to the protocols proposed in volunteers with better PF muscle activity. However, even if our data are not sufficiently conclusive, it is presumed that the preservation of PF muscle activity influenced the adherence, since in the domain of symptoms and functional quality of the quality of life questionnaire, the results were less favourable in women with a diagnosis of hypoactivity of this musculature. In addition, the number of occurrences of signs and symptoms was higher in these women. It is possible that the strength of the PF is a reflection of the degree of body consciousness. Self-knowledge and self-care may, as proposed by Carter et al. [36], directly influence adherence to prevention programs and gynaecological treatments and thus justify, at least in part, the results of our study.

The disorders resulting from brachytherapy treatment affect 30% of uterine cancer survivors [37], and impairments to quality of life tend to begin to improve 3–6 months after the end of radiotherapy [38]. This pattern of clinical response was evidenced in our findings, since quality of life improved significantly at the end of the follow-up. van Leeuwen et al. [39] followed the evolution of QoL in pelvic cancer survivors and found that the domains of functional quality and severity of symptoms improved significantly 1 year after the end of treatment. However, improvement in QoL was not influenced by treatment (use of dilators) and the effect of time was significant only when the data were grouped into a single group. This implies that it is enough to terminate the treatment for gynaecological cancer so that the QoL improves, so much so that in the intragroup analysis the CG had significant improvement in the functional quality.

Even with important deleterious effects, radiotherapy increases survival rates [37]. These effects arise from the involvement of healthy cells that are located around the irradiated region and the degree of reaction is directly dependent on the tissue sensitivity and dose used in the treatment [38]. The proportion of clinical signs and symptoms observed in volunteers in both groups was similar to the findings previously described by Ramaseshan et al. [40], where the acute effects that appear more frequently in the treatment of gynaecological cancer involve genitourinary, gastrointestinal and alterations of the vaginal mucosa including the presence of dryness, oedema and the presence of scars. However, at the end of the follow-up, there was a lower incidence of constipation, dryness and SUI in the treated group. Carter et al. [36] sought to evaluate the benefits of vaginal and sexual health treatment strategies and found that the resources used to improve hydration and flexibility of the vaginal mucosa and the use of VD as a means of developing awareness and proprioception of the PF were associated with the reduction of the symptoms resulting from treatment with gynaecological radiotherapy.

However, our findings demonstrate that the use of VD did not modify vaginal canal size 3 months after radiotherapy, and these results provide evidence that early use of dilators for the prevention of vaginal narrowing does not induce short-term benefits. On the other hand, there are indications that the use of VD can prevent vaginal narrowing as previously described [38,39,40,41]. In the observational and uncontrolled study by Velaskar Shruti et al. [42], vaginal canal length (average of 6 cm after 6–10 weeks of radiotherapy termination) was shown to increase with the use of VD (average of 9 cm after 4 months of vaginal dilation therapy). In this study, 89 women with cervical cancer treated with radiotherapy applied in the mode of teletherapy were included. Miles et al. [24] measured vaginal length and elasticity and found that the use of VD did not significantly alter these measures. Bahng et al. [43] observed in patients submitted to brachytherapy who used VDs at least two to three times per week (from 2 weeks after the end of radiotherapy), an increase in vaginal canal length (OR 0.17). In relation to the vaginal area, the available information is scarce. Only a recent study [44] evaluated the vaginal diameter before and after the end of radiotherapy and found a decrease of the area in only 11% of the evaluated sample. Similar results were observed in our study, where the vaginal area, evaluated through the size of the VD, remained practically constant throughout the follow-up. However, in the stratified analysis by adherence, a reduction in the vaginal area of the women allocated to the CG was found at the end of the follow-up. The impact of radiotherapy on the vaginal area is poorly described in the literature. As far as we know, there is no randomized clinical trial testing the effect of VD use on the measure. In addition, the vaginal area measurement strategy we use is a method not mentioned in the literature. This limits the comparison with other studies.

Law et al. [32] evaluated vaginal size with a strategy similar to that proposed in this study. They studied the efficacy and adherence to the use of VD in patients directed to use the dilators three times per week for 12 months, regardless of the number of sexual relations. At the initial assessment, vaginal canal size was determined from the largest dilator that could be inserted and maintained for 10 min without pain, tightness or bleeding. The efficacy of the treatment was defined when the dilator size was equal to the initial evaluation. The authors observed that VD size was lower in 49% of the volunteers in the 1 month after the end of radiotherapy. However, during the study, 52% of the reductions were reversed in 6 months of treatment. Our follow-up was only 3 months after the radiotherapy treatment and we had a high sample loss. The peculiar physical and physiological condition of these women could explain the consistent sample loss beforehand. As discussed in the “Introduction”, radiation causes damage to the vaginal epithelium, which may reduce tissue vascularization leading to pallor of the vaginal mucosa, loss of lubrication and inflammation. VD application may lead to an additional discomfort to the patient who probably does not perceive the benefit of the procedure.

Sexual activity and adherence to VD were not monitored; restrictions on the former were released from the fourth week of brachytherapy completion. This is a limitation and the evidence found in our study may be questionable, and different results to ours could possibly be observed in situations with better adherence, since in the stratified analysis we detected indications that the use of VD can help in the maintenance of the vaginal area because in the CG there was a significant reduction of this measure.

Another limitation of our study is the need to measure the dimensions of the vaginal canal before the start of teletherapy. However, most of the women referred to gynaecological brachytherapy in this service begin treatment with radiotherapy in other oncological centres. This same factor may have affected adherence to the follow-up in virtue of the displacement. Another important issue was the difficulty in controlling adhesion to the use of the dilator, a problem that we face because of a lack of feedback.

Although the estimated sample size was reached, the number of alterations in vaginal canal size was below predicted. In addition, the intervention and follow-up time was limited to 3 months and this probably explains the low incidence of anatomical changes and highlights the need for longer follow-up time to study this behaviour.

Conclusion

The effect of VD use in the first 3 months after radiotherapy does not have an acute effect on the length, width and area of the vaginal canal of women with cervical cancer, but the low adhesion to the study makes it impossible to extrapolate our results to this population. However, there are indications that VD can contribute to the improvement of PF muscle function and benefit the clinical evolution of these women, but studies with greater sampling power and longer follow-up should be conducted to clarify the possible benefits of this pelvic physiotherapy technique. Moreover, given the psychological resistance associated with the use of vaginal dilators, it is important to make women aware of the emotional and psychological barriers they might encounter in the rehabilitative dilator use, and possible solutions to these barrier, in order to improve adherence to the treatment.

References

IARC–WHO. In: Stewart B, Wild C, editors. World cancer report 2014. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014.

Vitale SG, Valenti G, Rapisarda AMC, et al. P16INK4a as a progression/regression tumour marker in LSIL cervix lesions: our clinical experience. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37:685–8.

Bakker RM, Mens JWM, de Groot HE, et al. A nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention after radiotherapy for gynecological cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:729–37.

Rossetti D, Vitale SG, Tropea A, Biondi A, Laganà AS. New procedures for the identification of sentinel lymph node: shaping the horizon of future management in early stage uterine cervical cancer. Updates Surg. 2017;69:383–8.

Jeppesen MM, Mogensen O, Dehn P, Jensen PT. Needs and priorities of women with endometrial and cervical cancer. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;36:122–32.

Vitale SG, Capriglione S, Zito G, et al. Management of endometrial, ovarian and cervical cancer in the elderly: current approach to a challenging condition. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299:299–315.

Izycki D, Woźniak K, Izycka N. Consequences of gynecological cancer in patients and their partners from the sexual and psychological perspective. Prz Menopauzalny. 2016;15:112–6.

Zomkowski K, Toryi AM, Sacomori C, Dias M, Sperandio FF. Sexual function and quality of life in gynecological cancer pre- and post-short-term brachytherapy: a prospective study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294:833–40.

Kokka F, Bryant A, Brockbank E, Powell M, Oram D. Hysterectomy with radiotherapy or chemotherapy or both for women with locally advanced cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD010260.

Marth C, Landoni F, Mahner S, McCormack M, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N. Cervical cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Supplement 4):iv262.

Bohr Mordhorst L, Karlsson L, Bärmark B, Sorbe B. Combined external and intracavitary irradiation in treatment of advanced cervical carcinomas: predictive factors for treatment outcome and early and late radiation reactions. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1268–75.

Wolf JK. Prevention and treatment of vaginal stenosis resulting from pelvic radiation therapy. Community Oncol. 2006;3:665–71.

Mouttet-Audouard R, Lacornerie T, Tresch E, et al. What is the normal tissues morbidity following helical intensity modulated radiation treatment for cervical cancer? Radiother Oncol. 2015;115:386–91.

Delanian S, Lefaix JL. The radiation-induced fibroatrophic process: therapeutic perspective via the antioxidant pathway. Radiother Oncol. 2004;73:119–31.

Bruner DW, Nolte S, Shahin MS, et al. Measurement of vaginal length: reliability of the vaginal sound—a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1749–55.

Lee Y. Patients’ perception and adherence to vaginal dilator therapy: a systematic review and synthesis employing symbolic interactionism. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:551–60.

Mohamed S, Lindegaard JC, de Leeuw AAC, et al. Vaginal dose de-escalation in image guided adaptive brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2016;120:480–5.

Lancaster L. Preventing vaginal stenosis after brachytherapy for gynaecological cancer: an overview of Australian practices. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8:30–9.

Park HS, Ratner ES, Lucarelli L, Polizzi S, Higgins SA, Damast S. Predictors of vaginal stenosis after intravaginal high-dose-rate brachytherapy for endometrial carcinoma. Brachytherapy. 2015;14:464–70.

Hofsjö A, Bohm-Starke N, Blomgren B, Jahren H, Steineck G, Bergmark K. Radiotherapy-induced vaginal fibrosis in cervical cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:661–6.

Kirchheiner K, Nout RA, Lindegaard JC, et al. Dose-effect relationship and risk factors for vaginal stenosis after definitive radio(chemo)therapy with image-guided brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer in the EMBRACE study. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118:160–6.

Bakker RM, Vermeer WM, Creutzberg CL, Mens JWM, Nout RA, Ter Kuile MM. Qualitative accounts of patients’ determinants of vaginal dilator use after pelvic radiotherapy. J Sex Med. 2015;12:764–73.

Bergin R, Hocking A, Robinson T, et al. Continuing variation and barriers to nurse-led vaginal dilator education for women with gynaecological cancer receiving radiotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;24:20–1.

Miles T, Johnson N. Vaginal dilator therapy for women receiving pelvic radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(9):CD007291.

Cullen K, Fergus K, DasGupta T, et al. Toward clinical care guidelines for supporting rehabilitative vaginal dilator use with women recovering from cervical cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1911–7.

Cullen K, Fergus K, Dasgupta T, Fitch M, Doyle C, Adams L. From “sex toy” to intrusive imposition: a qualitative examination of women’s experiences with vaginal dilator use following treatment for gynecological cancer. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1162–73.

Morris L, Do V, Chard J, Brand AH. Radiation-induced vaginal stenosis: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:273–9.

Loyd J, Crouch NS, Minto CL, Liao LM. Creighton female genital appearance: “normality” unfolds. BJOG. 2005;112:643–6.

Bernards AT, Berghmans BC, Slieker-Ten Hove MC, Staal JB, de Bie RA, Hendriks EJ. Dutch guidelines for physiotherapy in patients with stress urinary incontinence: an update. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:171–9.

Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, et al. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the pelvic floor clinical assessment group of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:374–80.

de Filho MR, Rocha BA, de Pires MB, et al. Quality of life of patients with head and neck cancer. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79:82–8.

Law E, Kelvin JF, Thom B, et al. Prospective study of vaginal dilator use adherence and efficacy following radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2015;116:149–55.

Ely GE, White C, Jones K, et al. Cervical cancer screening: exploring Appalachian patients’ barriers to follow-up care. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53:83–95.

Wordlaw-Stinson L, Jones S, Little S, et al. Challenges and recommendations to recruiting women who do not adhere to follow-up gynecological care. Open J Prev Med. 2014;04:123–8.

Rutledge TL, Rogers R, Lee SJ, Muller CY. A pilot randomized control trial to evaluate pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence among gynecologic cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:154–8.

Carter J, Stabile C, Seidel B, Baser RE, Goldfarb S, Goldfrank DJ. Vaginal and sexual health treatment strategies within a female sexual medicine program for cancer patients and survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:274–83.

Kirchheiner K, Czajka-Pepl A, Ponocny-Seliger E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder after high-dose-rate brachytherapy for cervical cancer with 2 fractions in 1 application under spinal/epidural anesthesia: incidence and risk factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:260–7.

Pfaendler KS, Wenzel L, Mechanic MB, Penner KR. Cervical cancer survivorship: long-term quality of life and social support. Clin Ther. 2015;37:39–48.

van Leeuwen M, Husson O, Alberti P, et al. Understanding the quality of life (QOL) issues in survivors of cancer: towards the development of an EORTC QOL cancer survivorship questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:114.

Ramaseshan AS, Felton J, Roque D, Rao G, Shipper AG, Sanses TVD. Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:459–76.

Lind H, Waldenström AC, Dunberger G, et al. Late symptoms in long-term gynaecological cancer survivors after radiation therapy: a population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:737–45.

Velaskar Shruti M, Martha R, Mahantashetty U, Badakare JS, Shrivastava SK. Use of indigenous vaginal dilator in radiation induced vaginal stenosis. Indian J Occup Ther. 2007;39:3–6.

Bahng AY, Dagan A, Bruner DW, Lin LL. Determination of prognostic factors for vaginal mucosal toxicity associated with intravaginal high-dose rate brachytherapy in patients with endometrial cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:667–73.

Martins J, Vaz AF, Grion RC, Esteves SCB, Costa-Paiva L, Baccaro LF. Factors associated with changes in vaginal length and diameter during pelvic radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296:1125–33.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to our study participants for their cooperation.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for the authorship of this article, and take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. They have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Salvatore Giovanni Vitale is a member of the journal's Editorial Board. Valentina Lucia La Rosa is a member of the journal's Editorial Board. Taís Marques Cerentini, Júlia Schlöttgen, Patrícia Viana da Rosa, Pierluigi Giampaolino, Gaetano Valenti, Stefano Cianci and Fabrício Edler Macagnan have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures involving human participants performed in this study were in accordance to the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia in Porto Alegre (CAAE: 63083516.4.0000.5335) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8175365.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cerentini, T.M., Schlöttgen, J., Viana da Rosa, P. et al. Clinical and Psychological Outcomes of the Use of Vaginal Dilators After Gynaecological Brachytherapy: a Randomized Clinical Trial. Adv Ther 36, 1936–1949 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01006-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01006-4