Abstract

We are developing the Equitable Screening to Support Youth (ESSY) Whole Child Screener to address concerns prevalent in existing school-based screenings that impede goals to advance educational equity using universal screeners. Traditional assessment development does not include end users in the early development phases, instead relying on a psychometric approach. In working to develop the ESSY Whole Child Screener, we are integrating a mixed methods approach with attention to consequential validity from the outset of measure development. This approach includes end users in measure development decisions. In this study, we interviewed a diverse sample of school staff (n = 7), administrators (n = 3), and family caregivers (n = 8) to solicit their perceptions of the usability of the initial draft of the ESSY Whole Child Screener. We identified three overarching themes: (1) paving the road for implementation of a whole child screener, (2) potential roadblocks to use, and (3) suggested paths forward to maximize positive intended consequences. Paving the road for implementation of a whole child screener includes subthemes related to alignment with existing initiatives, comprehensive yet efficient design, and potential positive consequences of assessing the whole child. Potential roadblocks to use includes subthemes of staff buy-in, family comfort with contextual screening items, teacher accuracy, and school capacity to provide indicated supports. Suggested paths forward to maximize positive intended consequences include clear and precise messaging to staff and families, optimizing instrumentation and data collection procedures, and strengthening connections to data interpretation and use. We discuss next steps in the design and testing of the initial measure as well as assessment development more broadly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although concerns have long existed in the US regarding educational inequities, the COVID-19 pandemic served to widen existing gaps in ways that are expected to be felt for some time (Bailey et al., 2021; Goldberg, 2021). It has been suggested that educational equity will be achieved when all students have the opportunities they need to reach their full potential (Moore et al., 2023; Osher et al., 2020); however, this requires multiple coordinated actions and efforts to transform the ways in which schools have historically operated. Among these, universal screening has been suggested as a means to promote equity by ensuring all students’ needs are systematically assessed, and students receive appropriate supports that match the intensity of those needs (Dever et al., 2016). Universal screening for academic or physical health concerns (e.g., reading and scoliosis) has long been employed in US schools, and universal social, emotional, and behavioral (SEB) screening instruments have begun to proliferate in recent years (Kim et al., 2021). Despite increased attention to universal screening assessments, however, several critical limitations of existing measures may impede intended efforts to promote educational equity.

First, existing screening instruments tend to take a siloed approach, focusing on one area of child development (e.g., reading, vision, and behavior). A recent survey by Briesch and colleagues (2021) found that 70–80% of school districts in the US engage in universal academic (e.g., literacy) and health (e.g., vision) screening, whereas as few as 9% of districts engage in any type of universal SEB screening. Such data suggest that school teams infrequently consider student SEB competencies in a systematic way when looking to proactively identify those students in need of supports. This is concerning given extensive evidence supporting the bidirectional link between academic and SEB challenges (McIntosh & Goodman, 2016). Furthermore, when SEB screening is employed, most available tools focus on SEB competencies to the exclusion of other areas of student functioning. For example, in their review of 26 SEB screening measures for use in schools, Brann et al. (2022) identified three measures that included assessment of academic enablers (i.e., BASC-3 Behavioral and Emotional Screening System; Elementary Social Behavior Assessment; Integrated Screening and Intervention System) and only two that directly asked about student academic performance (i.e., Kindergarten Academic and Behavior Readiness Screener, Social Skills Improvement System-Performance Screening Guide). As such, in order to consider the whole child, school teams must gather and synthesize screening data from multiple sources, and in the absence of such data, may have a more fragmented view of the whole child when making decisions about supports.

Second, historically, screening instruments have been characterized by a deficit focus, most often evaluating skills a student is lacking or problematic behavior they are exhibiting. For example, many screeners are designed to identify students demonstrating symptoms or indicators related to a particular diagnosis (e.g., emotional and behavioral disorder) to inform efforts that reduce symptoms. These screeners rely on the pathological medical model, locate and label behavior problems as deficits within the child (Briesch et al., 2016), and do not provide strengths-based data that can be leveraged to support successful interventions. There has, however, been a paradigm shift in recent years toward greater assessment of student strengths and skills, particularly in SEB domains (von der Embse et al., 2023). Consistent with the dual-factor model of mental health (Suldo & Shaffer, 2008), research has shown the assessment of student strengths to contribute meaningful variance in the prediction of student well-being (Kim & Choe, 2022; Kim et al., 2014). Despite this push, however, deficit-focused screeners continue to predominate in school-based settings with relatively fewer strength-based screeners available for use (e.g., Devereaux Student Strengths Assessment-Mini, Naglieri et al., 2011; Social Emotional Health Survey, Furlong et al., 2018).

Third, existing screeners miss opportunities to identify the root causes of student challenges by not collecting information about contextual assets or barriers that may underly symptoms (e.g., health-care access and food insecurity). Contextual assets and barriers include economic stability, education, social and community context, health and clinical care, neighborhood and physical environment, and food (i.e., social determinants of health; Henrikson et al., 2019; US Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). The practice of screening for contextual assets and barriers has begun to emerge in pediatric healthcare settings (e.g., Henrikson et al., 2019). Although not yet widely studied, a randomized clinical trial conducted by Gottlieb and colleagues (2016) indicated that such screening and subsequent connections to available services (e.g., childcare providers, utility bill assistance, and shelter arrangements) reduced family social need and improved children’s physical health 4 months later. As emphasized by Moore and colleagues (2023) in a recent special issue of School Mental Health on Advancing Equity Promotion in School Mental Health, “focusing on the individual student suggests that their ‘failure’ to cope or succeed is a personal deficit to remediate, rather than a societal or school failure” (p. 59). Despite the important information provided about a students’ lived experiences and circumstances, however, screening for contextual assets and barriers is rare in schools (Koslouski et al., 2024). For example, in a recent scoping review of the literature, Koslouski et al. (2024) were only able to identify six studies describing the development or use of a contextual screening instrument in school settings. Four of these occurred in K-12 settings and two in postsecondary contexts.

Lastly, existing measures have been developed without sufficient attention to consequential validity, or the intended and unintended positive and negative consequences of test use and score interpretation (Messick, 1998). Full understandings of the consequences of assessments, including universal screeners, are critical to advancing educational equity. Although evidence of consequences of testing is included as the fifth source of validity evidence in the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (AERA et al., 2014), the guidebook to measure development and evaluation, the consequences of test scores have been largely ignored (Cizek et al., 2010). Several potential reasons exist for the absence of consequential validity in research and measure development, such as disagreement about whether consequences should be included within the purview of validity, whether test developers or test users are responsible for evaluating consequences, and an absence of clear methods to evaluate consequences of testing (Cizek et al., 2010; Herman & Bonifay, 2023; Iliescu & Greiff, 2021; Norman, 2015). These reasons may unintentionally serve as contributors to educational inequities as negative consequences are left unexamined until damage has occurred (e.g., disproportionality). Evaluating consequences throughout measure development phases can offer opportunities to proactively identify revisions that can support intended positive consequences and mitigate negative unintended consequences.

Taken together, existing school screening instruments may unintentionally impede goals to promote educational equity by focusing on one area of development, emphasizing deficits within the child, neglecting contextual information that could be used to identify root causes of concerns, and placing insufficient attention on consequential validity in development phases. Although many available screeners can provide relevant information about a child, capacity to fully understand the barriers that prevent children from achieving their full potential is limited as resulting information does not view the whole child in context. A whole child approach in education recognizes that student learning and health are inextricably connected. The science of development and learning is driving recommendations for an integrated approach to school practices (Chafouleas & Iovino, 2021; Comer, 2020; Comer et. al., 2004; Darling-Hammond & Cook-Harvey, 2018). For schools to facilitate positive development across multiple domains (academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and physical) and contextual considerations, screening assessments must be comprehensive yet efficient in providing information necessary to inform integrated decisions across developmental pathways. Additionally, achieving intended goals of advancing educational equity through use of universal screeners requires attention to consequential validity throughout the measure development and evaluation phases.

To address the limitations described above, we are developing the Equitable Screening to Support Youth (ESSY) Whole Child Screener, which aims to be strengths-based, comprehensive (covering multiple domains), and contextual (i.e., assets and barriers in school, home, and community environments). The initial draft of the measure includes nine domains: academics, social skills, emotional well-being, behavior, physical health, student–teacher relationship, school experiences, access to basic needs, and social support. As described next, we are developing the ESSY Whole Child Screener with attention to consequential validity from the outset of development, asking intended users about the potential consequences of measure use to inform potential revisions to the measure before it is introduced into school settings. As discussed next, this represents a purposeful deviation from the ways in which measure development has traditionally been approached.

Attending to Consequential Validity by Integrating Mixed Methods in Measure Development

Traditional assessment development typically does not include end users, or those affected by data collection and use, in the early development phases (Bandalos, 2018; Boateng, 2018); however, isolated examples of including key groups throughout the development of a measure are available. For example, Cella et al. (2022), Simpfenderfer et al. (2023), and Ungar and Liebenberg (2011) collected multiple rounds of qualitative data in their measure development processes before engaging in quantitative psychometric evaluation of their measures. It is unfortunate that the solicitation of input from invested parties is relatively rare, as the overall lack of feedback from end users during early assessment development presents missed opportunities to proactively attend to the evaluation of consequences of testing.

To address this missed opportunity and increase attention to equity throughout the measure development process, the ESSY Whole Child Screener is being purposively developed using a mixed methods approach that attends to consequential validity. This framework builds upon traditional measure development approaches (Bandalos, 2018; Boateng, 2018) as well as contemporary mixed methods approaches (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2010; Sankofa, 2022). Our ten-step approach encourages integration of mixed methods, with purposeful attention to evaluation of consequences of testing throughout the measure development process. In doing so, this approach can facilitate proactive identification of revisions that support intended positive consequences and mitigate negative unintended consequences.

Allowing for multiple opportunities to collect qualitative and quantitative data, and to investigate potential consequences of use, the 10 steps of our approach to measure development are: (1) reflecting on goals and consequences, (2) identifying constructs, (3) developing items, (4) gathering initial item feedback, (5) cognitive pre-testing, (6) field testing, (7) using mixed methods data to refine the measure, (8) preparing guidelines for administration and data use, (9) conducting ongoing validation, and (10) updating implementation and data use guidance. This study focuses on Step 4: Gathering Initial Item Feedback, which includes evaluating perceived usability and potential consequences with intended users and those affected by data collection (Caemmerer et al., under review). Findings from this investigation will be used to revise the measure before cognitive pre-testing (Step 5) and then field testing to evaluate the measure’s quantitative psychometric adequacy (Step 6).

A usability framework can be helpful for examining the perspectives of intended users and those affected by data collection, as well as to consider issues of consequential validity (Caemmerer et al., under review). Usability is defined as “the extent to which a system, product or service can be used by the specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficacy, and satisfaction in a specified context of use” (International Organization for Standardization, 2018). Miller and colleagues (2014) identified six constructs of usability that may influence use of a given assessment in schools. Challenges in any of these areas may prevent an assessment from being implemented effectively in schools, whereas strengths in these areas indicate promise of the measure to be implemented as intended. Acceptability refers to the appropriateness of the assessment and participants’ interest and enthusiasm in using it. Understanding relates to participants’ knowledge regarding the assessment and associated procedures. Home–school collaboration refers to the extent to which participants feel home–school collaboration is necessary in supporting use of the assessment. Feasibility refers to ease of use, including the simplicity of the instrument and time required to use it. System climate relates to the compatibility of the assessment with the school environment, including alignment with current practices, administrator priorities, and the mission of the school. Finally, system support refers to the extent to which participants feel additional support is needed to carry out the assessment, such as professional development or consultative support. Although helpful, this framework does not explicitly address equity, a crucial piece of usability if measures are to achieve positive and equitable consequences. Thus, in this study, we investigate a seventh construct, equity, which we define as the extent to which participants perceive that the assessment instrumentation and procedures can minimize biased responses, promote fair assessment, and produce appropriate, accurate, respectful, and relevant consequences. Assessing usability directly aligns with Messick’s (1998) specified purpose for evaluating consequential validity: ensuring that measures are relevant to intended populations and inform positive change without creating undue negative consequences.

Despite its importance, the usability of school-based measures is not commonly reported. For example, in a recent systematic review, Brann et al. (2022) identified 128 studies evaluating 29 different school-based SEB assessments. Almost all (97%) of the studies evaluated technical adequacy of one or more of the instruments, but only 16% of the studies reported evaluations of usability. Those that did most often reported feasibility and acceptability of a measure after it was implemented. Only two studies provided preliminary investigations of perceived usability during item development. This may be, in part, due to lack of attention to perceived usability in traditional assessment development frameworks (Caemmerer et al., under review). Drawing on previous examples (Cella et al., 2022; Simpfenderfer et al., 2023; Ungar & Liebenberg, 2011), we stress the importance of soliciting the perspectives of intended users and those affected by data collection early in the measure development process. This can promote equity by including intended users in the measure development process and allowing for potential unintended consequences to be proactively identified and rectified before the measure is used in practice.

Study Aim

Prior to a large-scale field test to evaluate the quantitative psychometric properties of the ESSY Whole Child Screener, we conducted interviews with a diverse set of intended users (i.e., school administrators and staff) and those affected by data collection (i.e., family caregivers) to investigate the perceived usability and potential consequences of the screener. We aimed to identify perceptions of usability that would support implementation as well as concerns related to usability to inform measure revisions and plans for implementation. We also aimed to identify any potential unintended consequences of the measure’s use to drive work to mitigate any negative unintended consequences. Our primary research question was how do school staff, administrators, and family caregivers perceive the usability of the initial draft of the ESSY Whole Child Screener? Findings will inform measure revisions and allow us to plan for the consequential validity of the screener, a key component of ensuring outcomes generated by the measure strengthen educational equity. Findings may also highlight considerations for school administrators considering the adoption of any universal screening instrument, or a whole child screener specifically.

Methods

To plan for consequential validity and allow for responsive revisions before a large-scale field test, we interviewed school staff, administrators, and family caregivers to solicit their perceptions of the usability of the initial ESSY Whole Child Screener. We then used reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2021) to identify themes describing the perceived usability of the measure.

The ESSY Whole Child Screener

To maximize efficiency, we are developing the ESSY Whole Child Screener to use a multiple gated approach (Severson et al., 2007). In multiple gating, users complete a core set of items for all students. For example, a broad single item can serve as an “entry criterion” item for each construct (Gate 1; e.g., academics, social, and emotional). If the entry criterion is rated as present or an area of concern, respondents are asked additional questions (Gate 2) to collect more information. In this way, the measure remains efficient and cost-effective because teachers complete the entry criterion for all students (universal), but only complete follow-up items for a subset of students for whom they have expressed areas of concern (Severson et al., 2007).

The initial draft of the ESSY Whole Child Screener includes 13 items at Gate 1, which are completed by the classroom teacher for all students in grades 3–5. The first eight questions each address a domain of interest using a single question (e.g., How would you rate this student’s social skills [e.g., degree to which the student has social connections, gets along with others, demonstrates prosocial behavior]?). Response options include area of substantial concern, area of concern, neither an area of strength nor concern, area of strength, and area of substantial strength. Gate 1 domains include academics, social skills, emotional well-being, behavior, physical health, school experiences, access to basic needs, and social support. Also at Gate 1, the initial draft of the measure includes four items related to the teacher’s perception of their relationship with the student, and one question assessing the teacher’s confidence in their ratings.

If a teacher reports no concern or no substantial concern across all Gate 1 items, screening for that student would conclude. For each indicated area of concern or substantial concern, an additional 5–9 items are presented (Gate 2). These items ask more specific questions related to the area of concern (e.g., social skills: has friends/social connections, interacts appropriately with adults) to narrow in on specific areas of strength and difficulty. In summary, teachers may complete as few as 13 questions for students for whom they have no areas of concern. If all areas are endorsed as areas of concern, however, the total number of gate one and gate two items is close to 70 items.

Data Collection

Participants and Recruitment

School staff, administrators, and family caregivers were purposively sampled to solicit perspectives from those with diverse experiences and expertise. We recruited school staff and administrators across a range of roles related to school-based screening, and family caregivers from a variety of communities and backgrounds. After obtaining approval from the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited through district and community partners that were participating in the larger project to develop the screening instrument. A recruitment flyer was shared with administrative contacts in each of the districts, and administrators were asked to share the flyer with eligible participants. Eligible participants included third–fifth grade teachers, school mental health professionals, family liaisons, administrators, and family caregivers of third–fifth grade students. The recruitment flyer contained a link to a description of the study, consent form, and a demographic questionnaire.

Seven school staff (four teachers, two school mental health professionals, and one family liaison), three school administrators, and eight family caregivers provided informed consent to participate in this study. School staff and administrators had an average of 10.1 years of experience (range: 1–25 years) and worked in three different school districts in the northeastern US. Five of the eight (62.5%) family caregivers had at least one child with an identified disability, and two (25.0%) had previous teaching experience. See Table 1 for sample demographics and Table 2 for participant attributes.

Interview Procedures

All interviews were conducted via WebEx by the first author or trained graduate research assistants using a semi-structured interview protocol. After introductory questions asking about participants’ experiences with school-based screening, the interviewer shared their screen to display each section of the ESSY Whole Child Screener. While viewing each section, participants were asked: (a) their reactions to the section and items, (b) whether the items were relevant to a school setting, (c) whether school personnel would be able to accurately report on the items, (d) if the items would capture students in need of support, (e) the amount of time that would be needed to complete the items for one student, (f) if any topics or items were missing, and (g) if any items were overly ethnocentric or could induce bias or stereotyping. Questions a–f align with Miller and colleagues’ (2014) constructs of usability (e.g., acceptability and feasibility), whereas (g) was added to explicitly evaluate the construct of equity.

After reviewing the sections of the screener with the participant, the interviewer stopped sharing their screen and asked questions about ideal methods for data collection and data reporting, positive and negative consequences that could result from measure use, any additional informants needed (e.g., student), the appropriateness of assessing contextual assets and barriers in the school setting, and any additional recommendations or feedback. Some questions were tailored to participants’ specific roles and expertise. When asking family caregivers about data collection and reporting, we specifically asked what type of information they would hope to receive if their child’s school used the screener. For school staff and administrators, we asked about supports and efficiencies related to both data collection and interpretation. In later development stages of the ESSY Whole Child Screener, we plan to provide sample data reports and seek feedback from intended users.

The semi-structured interview protocol allowed for follow-up prompts requesting elaboration or clarification. Interviews lasted 52–101 min (M = 70 min), were audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim using Otter.ai. Transcripts were de-identified and verified by trained research assistants. Participants were given a $50 gift card in appreciation of their time.

Data Analysis

We used reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2021) to investigate school staff, school administrators, and family caregivers’ perceptions of the usability of the ESSY Whole Child Screener. Each de-identified transcript was uploaded into NVivo 14 (QSR International, 2023). As recommended in reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021), we inductively coded each transcript, allowing for codes to be developed from participants’ perspectives and insights, rather than pre-specified codes generated by the research team. The first and fifth authors completed the coding. Before beginning to code, they met to discuss the research question, usability constructs, and procedures for inductive coding.

The first and fifth authors began by coding the first two transcripts. Each independently developed codes to describe the participants’ perceptions of the usability of the ESSY Whole Child Screener. After coding each transcript, they each wrote a memo, detailing impressions and a description of the participant’s perspectives related to the usability of the measure. After coding the data for the first two participants, the first and fifth authors met to discuss their interpretations and combine codes. They continued to meet weekly, discussing and combining codes after each 3–5 transcripts. Codes were merged or grouped around similar ideas such as recommended revisions; concerns related to bias, feasibility, or accuracy; and recommendations for strengthening data use. After the data of all 18 participants were coded, the first author reviewed the full dataset to ensure all relevant data were coded.

Once initial coding was completed, the first author organized the codes into groups of related ideas to explore potential themes. She included examples to help define each idea and noted any codes that seemed to contradict others or not to fit. Next, she created an initial thematic map to explore how the codes and potential themes related to one another. She then met with the fifth author to discuss and refine the potential themes. The first author continued to draft new project maps exploring how the codes related to one another, and reflected on the strengths and shortcomings of each map with the second and fifth authors. This led to the organization of subthemes into three overarching themes. Once the first and fifth authors considered the themes and subthemes to accurately represent the data and answer the research question, the first author reviewed all of the coded data and transcripts to confirm that the potential themes represented the original data and were distinct from one another. While reviewing, she looked for additional data as well as contradictory evidence (Creswell & Miller, 2000). She then examined whether any subthemes were particularly salient with a subgroup of participants (e.g., administrators or family caregivers) and defined each theme for the story it tells (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2021). The fifth author reviewed these descriptions for accuracy and comprehensiveness. In total, five provisional maps were created to explore potential relations and themes. Table 3 presents example codes that were included in each subtheme to illustrate how codes were grouped together.

Researcher Reflexivity

Throughout the study, we considered our own positionalities as they related to the data and research question. Our team is designing the ESSY Whole Child Screener and, thus, is invested in its usability and consequential validity. Although this could bias us toward presenting more complimentary data, we are committed to addressing concerns related to usability at this stage of the measure development process to increase the likelihood that the measure is found to be usable when implemented in schools. We also recognize that despite our goal to increase equity using this instrument, we have blind spots and biases. Thus, feedback from participants related to overly ethnocentric items or items that might induce bias was particularly valued. Our approach to measure development, which prioritizes the inclusion of intended users’ perspectives throughout the measure development process, signals our values, and was used to check our own biases and assumptions in this study.

Measures to Increase Trustworthiness

We took several steps to increase the trustworthiness of this study. The research team maintained an audit trail of memos throughout the interviewing, coding, and analysis phases to document key ideas brought forth in each interview, coding decisions, descriptions and shortcomings of each new thematic map, and the rationale for each reorganization of the data. We included many participant quotes in our findings section to remain close to the data and to illustrate participants’ perspectives and insight. Lastly, we searched for disconfirming evidence (i.e., evidence contradictory to other findings; Creswell & Miller, 2000) to ensure that our findings accurately represented participants’ perceptions of the ESSY Whole Child Screener.

Findings

We identified three overarching themes, each with subthemes, related to the usability of the initial ESSY Whole Child Screener: (1) paving the road for implementation of a whole child screener, (2) potential roadblocks to use, and (3) suggested paths forward to maximize positive intended consequences.

Paving the Road for Implementation of a Whole Child Screener

Paving the road for implementation of a whole child screener includes subthemes related to perceived promise of the measure and its alignment with existing priorities and goals: alignment with existing initiatives, comprehensive yet efficient design, and potential positive consequences of assessing the whole child.

Alignment with Existing Initiatives

Participants described that key features of the screener aligned with existing work in schools, laying the foundation for the usability of the measure. Administrators described that screening the whole child aligned with their districts’ less formalized work to support students and families. Administrator #3 shared, “We’re not only supporting the academic side, but we’re also addressing barriers that families face, whether it’s food, homelessness, any number of barriers. […] We address all those questions on a daily basis with families.” School staff engaged in providing families with these supports spoke about the potential benefits of standardizing this work, including improved organization, efficiency, and accountability mechanisms through which to provide needed supports. Administrators also noted alignment with current efforts to support student mental health and engage multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS). These examples suggest usability in the areas of acceptability and system climate, as participants expressed enthusiasm for using the measure and alignment with their current practices.

Comprehensive yet Efficient Design

Many participants remarked on the comprehensive yet efficient design of the initial measure and how this supported its usability. Participants did not feel that any domains of student functioning were missing. School staff #3 shared, “It’s seeing that human as a whole child: physical needs, social emotional needs, what are the needs of their family, and tapping into those different aspects that make the child.” Participants expressed that the plan for multiple gating supported efficiency and feasibility. Family caregiver #3 explained, “[Gate 1] is really short. But a lot of information.” Administrator #1 noted, “The most valuable resource to have in schools is time. So having a really efficient process to do that is really, really important.”

Potential Positive Consequences of Assessing the Whole Child

Participants noted many potential positive consequences to assessing the whole child and felt these laid the foundation for the usability of the screener. First, participants felt that the strengths-based focus improved on existing screeners, and the resulting data would be beneficial. Some suggested that schools could use the data to identify student leadership opportunities, or to leverage strengths to help remediate areas of challenge. Administrator #1 shared, “One of the benefits of having all those assets is that if challenges were to present for a student, we can leverage those assets.”

Next, participants expressed that comprehensive screening would improve schools’ identification of the root causes of student challenges and enhance both teacher and school team understandings. Administrator #1 shared that schools often struggle to accurately define a problem. They elaborated, “We’re seeing a set of behaviors, but there could be a lot of reasons for that. And so, I think this type of screener is getting at the different reasons why a child might be struggling.” Administrator #1 stressed the importance of a strong problem definition in identifying focused interventions to put in place. Family caregiver #7 commented that the screener might lead to more targeted and relevant interventions. They shared that past solutions tended to be a Band-Aid, “but not a holistic solution because it wasn’t a holistic approach.”

Multiple participants commented that the tool could also prompt teacher reflection and broaden their understandings of the various factors that influence student learning and behavior. School staff #3 shared, “It makes you think deeper into the child’s life and life outside of school. Because we think, ‘oh, our school is so important, it’s the only thing that matters.’ But in reality, I think there are so many other layers to this child we need to think and talk about.”

Participants perceived that the screener also had the potential to increase communication among staff and between educators and families. Administrator #2 described, “It brings more people around the table having conversations around the whole child approach to schooling.” Family caregiver #6 shared, “I’m seeing this as kind of filling the gap and building a better relationship between the school and families. […] Because sometimes people don’t know that resources exist to help them. And so, could this be the starting point?” Some even expressed that the use of the universal screening tool may help to reduce stigma related to needing support. School staff #7 expressed that this type of screener could help to normalize the need for assistance, and due to its universal nature, prevent families from feeling isolated or singled out.

A final perceived benefit to whole child screening was the opportunity to use data to inform proactive classroom, grade-level, and school-wide interventions. For example, Administrator #2 shared, “It identifies gaps that may have been present, or barriers that we may have inadvertently placed in our schools or classrooms.” Administrators saw opportunities to use the data to evaluate current initiatives (e.g., social and emotional learning curriculum) within and across different student populations and to inform resource alignment and allocation.

In sum, participants noted alignment of the screener with existing initiatives and positive features of the screener, including its comprehensiveness, efficiency, and potential to generate positive consequences. Participants felt that the screener could strengthen existing school-based efforts to support the whole child, offering more formalized, efficient, and effective identification of targeted supports.

Potential Roadblocks to Use

Despite the positive foundation described above, participants cautioned that roadblocks may exist to use of the ESSY Whole Child Screener as conceptualized within this initial draft. These included faculty and staff buy-in, family comfort with contextual screening items, teacher rating accuracy, and school capacity to provide indicated supports.

Faculty and Staff Buy-In

Participants cautioned that school faculty and staff may be skeptical of another assessment tool and school-wide initiative. They warned of the revolving door of initiatives in education, and the time demands placed on teachers. For example, School staff #2 shared that their district had recently implemented an SEB screener, explaining, “So, if you’re saying we’re getting rid of that one and replacing it so soon, I think people will have a hard time accepting that. Because we didn’t see if there was any success with the first one.” Participants also noted poor data use as a barrier to faculty and staff buy-in. School staff #4 shared, “A lot of times we’re asked to do things like this, and it feels like it just kind of goes into a pit and the data is not really used well.” They noted how frustrating this was for those who had invested time into collecting data and had hoped to see positive consequences as a result of their efforts.

Administrators and family caregivers, in particular, also warned that staff may be uncomfortable with items inquiring about the quality of the relationship between them and each student. Administrator #2 explained that the questions may pose risks for teachers. They shared, “What teacher wants to go in thinking they don’t have a strong and positive relationship with a student? I think teachers may worry that would reflect poorly on them, especially if they’re in meetings with their supervisors and evaluators.” Family caregiver #2 shared, “I don't think it puts the staff in a safe situation.” As such, these questions might jeopardize faculty and staff buy-in.

Family Comfort with Contextual Screening Items

Participants also expressed concern related to families’ comfort with contextual screening items, noting that some family caregivers may feel judged or scrutinized by these items. School staff #5 explained, “I think for a lot of our students, if a parent is asked whether their kid is hungry or not, they might feel like they’re not doing their job as a parent, that they’re not providing for their family.” Some participants felt that parents might worry about the purpose of the items, and that information could be used against them (e.g., reporting to authorities). Family caregiver #8 explained, “I feel like there’s an issue with parents trusting the school, because schools are so quick to report them. So, they’re like, ‘I’m not trusting you in aiding me, because you're just going to make things worse for me.’” Administrator #3 worried that formalizing these types of questions could isolate families, explaining, “I’d hate to use the screener, and then isolate families, because they feel like, ‘Gee, the teachers are saying that I’m a failure, a failing parent because I don’t communicate or I’m a failing parent because of that.’.”

Teacher Rating Accuracy

Next, participants expressed concern that teachers may not be able to accurately rate items related to students’ access to basic needs, social support, school experiences, emotional well-being, or physical health. For example, School staff #1 shared, “Home supports and the access to basic needs, unless the family or child shares that, I’m not sure that we know that for all students.” Participants also noted that contextual screening items inquiring about stressful life events or safe routes to school may be too subjective. School staff #6 described, “A safe route may be safe for me, but not safe for you. What is a safe route? What’s not a safe route? Does the child feel safe?” Others noted similar concerns about items assessing stressful life events, noting that what might be perceived as stressful to a teacher may not be to a child, or vice versa.

Participants stated that teachers may not be able to accurately rate students’ experiences in school, including having a trusted adult, a friend, or experiencing discrimination, cultural belonging, or bullying. School staff #3 explained, “I feel like what you perceive as a student’s school experience might not be what they’re experiencing. I might think they have a friend, but maybe they don’t. Maybe I don’t know about discrimination they’ve experienced.” Participants also shared that teachers would likely have difficulty accurately rating students’ internal experiences of emotional well-being, including life satisfaction and sense of meaning. Family caregivers, in particular, emphasized individual and cultural differences in children’s displays of social withdrawal and positive affect and felt these needed to be taken into account.

School Capacity to Provide Indicated Supports

Lastly, participants expressed concern that schools might not be able to connect students to indicated supports and reflected on the ethical implications of this. Administrator #1 expressed, “If you don’t use those data, you’re sort of just wasting people’s time, right?” Participants warned that flagging concerns without providing supports might cause alarm and be unhelpful. In addition, because of the amount of resources needed to complete the screening, participants felt that staff and family buy-in would be jeopardized if schools were not able to follow up with indicated supports. Participants also raised concerns about teacher accuracy in light of supports that may need to subsequently be provided. Family caregiver #2 expressed concern that some districts may hesitate to flag concerns because there may be financial implications related to providing needed services. They articulated, “are [school districts completing this measure] taking the time to follow up with services? Or, are staff members going to be expected to not flag certain things because they can’t afford an uptick in 504 services?”

In summary, participants identified some potential roadblocks to the usability of the drafted screener, including staff and family buy-in (acceptability and equity), family comfort with contextual screening items (acceptability, system climate, and equity), teacher rating accuracy (feasibility and equity), and schools’ abilities to follow up with indicated supports (feasibility, system climate, and equity).

Suggested Paths Forward to Maximize Positive Intended Consequences

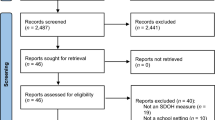

Participants made several recommendations to address these potential barriers and to maximize positive intended consequences. Specific recommendations included clear and precise messaging with staff and families, optimizing instrumentation and data collection procedures, and strengthening connections to data interpretation and use. In Fig. 1, we show the alignment of these recommendations with the roadblocks identified above.

Clear and Precise Messaging with Staff and Families

Participants suggested that clear and precise messaging with school staff and families could help to alleviate some of the potential roadblocks and concerns discussed above. Specific to school staff, participants stressed the importance of describing the purpose of the screener, explaining relationships between the various domains and student performance, and detailing how data could be used to improve student outcomes. School staff #3 shared, “I could foresee some teachers saying, ‘This takes way too much of my time. I don’t understand why they’re asking all these questions.’ So, teaching us teachers that we have to think about the whole child.” Participants suggested also messaging how the measure fits in with other assessments completed at the school, and whether this could serve as a more efficient way to collect data (e.g., replacing other assessments). School staff #2 suggested first piloting the measure with a small number of teachers and then sharing outcome data to generate buy-in more broadly. They explained, “[Do] a trial run first to see how it works out in a couple classrooms and say, ‘These are the successes we’ve seen, it has identified X amount of kids.’.”

Participants suggested that without careful work, the measure might hurt relationships between schools and families, yielding a potential negative and unintended consequence of the measure. Participants suggested that very clear messaging about the purpose of the measure needed to be shared with families. School staff #5 emphasized the importance of messaging: “We’re asking this so we can connect them with this support because we feel like this may impact their academic performance or development. To just be upfront about that and making it clear and precise.” Family caregiver #7 reflected on how messaging could help to alleviate families’ concerns about the purpose of the measure. They explained:

When teachers and educators take the time to say, “We’re here to help, and it’s not anything that you’ve done wrong, and we really want to help your kids be as successful as possible.” I think that that helps take the edge off, and really helps parents to be able to not only educate them, but also educate the kids.

Participants felt that clear and precise messaging would be critical to generating buy-in from staff and families.

Optimizing Instrumentation and Data Collection Procedures

Participants made several suggestions related to optimizing the instrumentation and data collection procedures. These included revisions to specific items, staff training in use of the measure, and the consideration of a multi-informant approach. Item revisions included adding, deleting, and editing specific items to improve clarity and reduce the potential for bias. For example, participants suggested removing words such as aggressive, malicious intent, overactive behaviors, risky rule breaking behavior, and excessive talking as they might induce bias. They commented that items inquiring about children’s caretaking responsibilities or living with relatives may be overly ethnocentric as these are customary experiences in some cultures. Some participants suggested renaming “access to basic needs” to “access to material needs” to reduce the potential for caregivers to feel judged or embarrassed by these items. Many participants also suggested adding items that inquired about whether students had an identified disability, chronic health condition, or were an English language learner to contextualize responses to other items.

Participants also had suggestions for optimizing data collection procedures. They felt that faculty and staff training on the areas assessed by the screener, how these relate to school performance, and guidance for reducing bias would improve the measure’s usability. Many participants also encouraged consideration of a multi-informant approach to increase feasibility. Within schools, this might include the school nurse, social worker, or physical education teacher filling out specific items related to their expertise and knowledge of students. Participants expressed that a multi-informant approach could reduce the time burden on classroom teachers, and potentially increase the accuracy of responses.

Participants also conveyed that an additional informant, such as a student or family caregiver, would be beneficial for specific areas of the screener (i.e., student: student–teacher relationship, emotional well-being, and school experiences; family caregiver: access to basic needs and social support). For example, Family caregiver #2 shared, “Some of those [emotional well-being] questions, you would only get the data if a child was self-reporting. Especially the language that’s like, ‘student appears’ or ‘student feels.’ You can’t really comment on that without inviting them into the conversation.” Related to a family caregiver informant, School staff #4 reflected on filling out social determinants of health screeners at the pediatrician’s office. She shared, “That feels better when you’re volunteering that information [rather] than someone else making that judgment for you. […] I think it might feel better for parents to identify those needs themselves.” Some family caregivers also noted that they could answer the questions much faster than school personnel could observe them, expediting problem-solving and identification of needed supports. Participants felt that a multi-informant approach could improve feasibility (e.g., accuracy and efficiency), home–school collaboration (family buy-in), and equity (minimizing bias in responses, producing appropriate, accurate, and respectful consequences).

Strengthening Connections to Data Interpretation and Use

Participants also suggested strengthening connections to data interpretation and use to increase the feasibility and efficiency with which schools are able to act upon data generated with the screener. First, participants recommended prioritizing the usability of data reports to aid data interpretation. They suggested that data reports be color coded, indicate areas of strength and concern, and suggest potential supports. Some participants recommended prioritizing areas of concern or offering entry points to school staff. For example, Administrator #3 shared, “If I’m a teacher and I have this amount of information for every child, where’s my entry point? Because it could be overwhelming.” Participants suggested that some information might be flagged as an immediate need, whereas other information might be provided to inform educators’ interactions with students. Participants noted that this would need to happen at both the student and school levels (i.e., What is the highest priority for this student? To which students do we need to provide supports most urgently?).

Finally, participants stressed that schools need to be ready to provide supports in response to the screening data. Administrator #3 summarized,

We need to make sure that we have the resources and the support system in place. So kids can come to school and not be worried about breakfast or worried about lunch. Take food home on the weekend. So they know, “I have a partner at school, I have a community at school that’s going to take care of me as well.”

Some suggested that a tool might be created to help schools map available and appropriate supports for the various areas assessed by the screener. For example, School staff #4 explained, “[helping schools] think through, okay, when students pop up in this domain, who can the teacher get more help from? When they pop up in this domain, you know, so it’s institutionally mapped out a little bit.” Participants emphasized that this would help schools to efficiently connect students with supports indicated by the screening results, which would increase the acceptability of the screener with school staff and families.

Discussion

As an early step in our measure development approach, this study investigated the perceived usability of the initial draft of the ESSY Whole Child Screener. We found that school administrators, school staff, and family caregivers perceived that several factors paved the way for implementation of a whole child screener in schools. These included alignment of the screener with existing initiatives, its comprehensive yet efficient design, and the potential positive consequences of assessing the whole child. Participants also identified several potential roadblocks to use of the measure, and paths forward to address these roadblocks. Early identification of these strengths and areas for improvement allows for responsive revisions to be made before conducting a large-scale field test to evaluate the quantitative psychometric properties of the measure. This study also allowed us to proactively identify potential positive and negative consequences of the screener. By collecting these data early in the measure development process, we can now plan for use that facilitates positive intended consequences and mitigates identified negative unintended consequences.

Participants stressed the importance of faculty and staff buy-in to the success of the screener, as well as key challenges to gaining staff buy-in. Teachers’ professional responsibilities are vast and ever-evolving, and it is not uncommon for new initiatives to quickly be replaced in schools. Participants in this study identified concerns related to the negative unintended consequence of initiative overload, whereby teachers feel cynical toward any new initiative, not sure that the time and effort they invest in learning it will be worthwhile (Blodgett, 2018). Because the ESSY Whole Child Screener relies on teacher report, and therefore, teachers’ time and effort, faculty and staff buy-in is critical to avoid this potential negative consequence. Although feasibility can be increased by providing teachers with allocated time to complete the screening, the accuracy and consequences of screening results rely, in part, on teachers’ careful attention and reflection on each student. Thus, building faculty and staff’s understanding of the purpose and value of the screener will be important. For example, training in how each area assessed by the screener affects student learning and performance, and the potential positive consequences of data collection may help to increase support for the screening efforts. Positive consequences could include reduced special education or discipline referrals due to earlier, proactive identification of concerns. Buy-in is likely to be reinforced over time through demonstration of effective data use (e.g., collaborative interpretation and connection to supports).

The ESSY Whole Child Screener differs from many existing school-based screeners in that it includes contextual screening items (e.g., social determinants of health), including students’ experiences of social support, economic stability, and food security. This type of screening is rare in schools and is typically conducted through student or family caregiver report (Koslouski et al., 2024). Because US teachers are not immune to the biases held by any other adults (Starck et al., 2020), and school personnel in most US states are mandated reporters in the case of suspected child abuse or neglect (US Government Accountability Office, 2014), families may be apprehensive or opposed to teachers reporting on this information. Thus, a potential negative unintended consequence identified in this study is screener results damaging relationships between families and schools. Potential paths forward include clear and precise messaging to families about the purpose of the screener and the influence of contextual assets and barriers on student learning and performance. Reassurance that data are being collected to connect students to needed supports may help to generate family buy-in, and this could be reinforced over time through effective and efficient provision of supports. Additional options include adding a family report section to the screener, in which family caregivers are asked to self-identify contextual assets and barriers in the student’s life. Although this may reduce concerns related to teacher bias and undesired disclosure, it introduces new concerns related to incomplete data because of challenges engaging families in school-based screening efforts (e.g., Sokol et al., 2022).

Participants also identified areas of the ESSY Whole Child Screener where they were concerned that teachers may not be able to accurately rate students. These included areas focused on students’ internal experiences (e.g., emotional well-being and school belonging) as well as those in their homes and communities (e.g., social support and access to basic needs). Participants noted that these items required a close relationship with the student, and even then, teachers may not be privy to the information. This could generate negative unintended consequences such as incomplete or inaccurate data or biased responses. Participants made specific recommendations for item revisions that may help with accuracy (i.e., clarifying language and removing emotionally laden language) as well as the potential for staff training to increase understanding of the various areas being assessed by the screener. Teacher accuracy can be assessed during psychometric testing through studies of concordance between teacher, student, and family caregiver ratings. Should teacher accuracy remain a concern, a multi-informant approach will likely be needed to generate accurate screening information across the many domains assessed by this measure.

Lastly, participants expressed concern and ethical considerations related to schools’ capacities to provide supports indicated by screening data. As noted by Meier (1975), collecting screening data without planning for or providing follow-up supports not only wastes resources, but may also result in negative unintended consequences (e.g., labeling and stigmatizing) for those identified by the screening process. Participants in this study were concerned about potential negative consequences related to wasted time and effort and causing alarm if supports cannot be provided. Our findings, however, also highlighted opportunities to maximize teachers’ and schools’ meaningful use of generated data. Data reports and reporting structures that prioritize usability and allow school staff and administrators to aggregate and disaggregate data to inform decisions about individual or group interventions, school-wide priorities, and resource allocation are likely to facilitate data use. In addition, structures to help schools proactively map appropriate supports to areas of need identified by the screener may increase the efficiency of connecting students with supports. Participants noted that their schools already provided many of the supports that would be indicated by the screener; thus, the challenge may be less about finding the supports, and more about expediting connections to supports for students.

The barriers to usability identified in this study are not unique; rather, they align with those identified more than 15 years ago by Severson and colleagues (2007). Specifically, Severson and colleagues identified faculty and staff buy-in, teacher rating accuracy, and effective data use as key challenges to the implementation of universal screening measures in schools. However, whereas researchers have historically waited to examine usability until measure development is complete, the current usability study was designed to serve as an early step in the measure development process. Similar to the work of both Ungar and Liebenberg (2011) and Cella and colleagues (2022), our approach facilitated inclusion of the perspectives of intended users, and those affected by data use early in the measure development process. In addition, our data collection allowed us to understand barriers to the usability of our initial draft of the measure and any potential negative unintended consequences. We can now work to prevent these barriers and negative consequences through measure revisions, implementation planning, and continued evaluation and refinement based on the input of key groups.

Initial Revisions to the ESSY Whole Child Screener

This study points to several revisions to the ESSY Whole Child Screener to promote positive intended consequences and address some of the identified negative unintended consequences. First, we will add items asking whether a student has an identified disability, chronic health condition, or is an English language learner to aid with data interpretation and use. We will revise or remove several words or phrases that were flagged by participants as potentially inducing bias (e.g., aggressive and malicious intent). We also plan to change the wording of some items designed to assess contextual factors to reduce concerns about judgment toward families. We will remove some items that participants felt could not be rated by teachers, are less relevant to elementary-aged children, or might induce bias. Based on participants’ insights, we plan to add items related to overly clingy behaviors and ability to cope with emotions, and divide unmet physical and oral health needs into two questions because participants noted that these were not always correlated for students (due to health and dental insurance being separate in the US). As illustrated by these examples, asking intended users, and those affected by data collection, about perceived usability and potential consequences of the measure yielded tremendous insight with which we can revise the ESSY Whole Child Screener for cognitive pre-testing and a large-scale field test. These revisions will be combined with continued planning for data use (e.g., developing a user-friendly data report, clear and precise messaging to staff and families) and ongoing mixed methods evaluation to promote positive consequences and mitigate negative unintended consequences.

Limitations and Future Directions

It is important to consider the limitations of this study. Interviews were conducted with a convenience sample, and thus, likely represented individuals interested in whole child screening. Although we were able to interview a diverse sample of school personnel and family caregivers (with regard to racial and ethnic identity, professional expertise, and experience with children with disabilities, for example), our findings may not have captured the full range of perspectives that would inform equitable implementation. Interview participants were also based in northeastern US school districts that primarily engage in SEB screening. This suggests familiarity with universal screening beyond academic and health (vision and hearing) domains. In some areas of the US, social and emotional learning (SEL) has come under attack due to inaccurate conflation with Critical Race Theory (Abrams, 2023). Individuals opposed to SEL may not feel as favorably about whole child screening as the participants in this study did. Furthermore, because the measure is still in development, this study only evaluated perceived usability and potential consequences. Additional studies will be needed to evaluate actual usability and consequential validity as the measure is implemented in schools. That said, the purpose of this initial investigation was to inform revisions to the measure to optimize its development and implementation, with a goal of improving outcomes of future usability and consequential validity studies. Lastly, the quantitative psychometric properties of the ESSY Whole Child Screener are not yet known. These need to be evaluated before the measure is implemented in schools. However, this study allows for responsive revisions to be made to the measure before engaging in a large-scale field test.

This study points to several important future directions. Continuing to use a mixed methods approach that attends to consequential validity, next steps include revision of the ESSY Whole Child Screener based on the findings of this study, cognitive pre-testing, further revision, and large-scale psychometric evaluation. We plan to interpret results of the psychometric testing alongside qualitative data to inform revisions to the measure (for an example, see Ungar & Liebenberg, 2011). This approach to measure development prioritizes planning for consequential validity by including the perspectives of intended users, and those affected by data collection throughout the measure development process.

Studies of teacher, family caregiver, and student concordance will help to identify whether teachers can accurately report on all domains assessed in the initial version of the ESSY Whole Child Screener, or if a multi-informant approach is needed. Because teachers themselves did not raise concerns about the student–teacher items (but administrators and caregivers did), we plan to test these items to determine whether there is variance in ratings, which will indicate whether teachers are willing to report less favorable relationships. Additional research is needed to determine if and how contextual questions can be asked to generate acceptability with families, teacher accuracy, and positive intended consequences. These investigations also need to evaluate whether any negative, unintended consequences arise from the inclusion of these items. Lastly, once structures are developed to guide data interpretation and use, treatment utility (i.e., decisions made in comparison with those made with existing screeners; Hayes et al., 1987) should be tested with school staff. Key questions include whether positive consequences can be generated over and above existing screening efforts, and whether any provided data interpretation structures can increase the feasibility of acting upon generated data.

References

Abrams, Z. (2023, September). Teaching social-emotional learning is under attack. Monitor on Psychology, 54(6). Accessed November 17, 2023 from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/09/social-emotional-learning-under-fire

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education (Joint Committee). (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: Authors

Authors. (Under review).

Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Murnane, R. J., & Au Yeung, N. (2021). Achievement gaps in the wake of COVID-19. Educational Researcher, 50(5), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211011237

Bandalos, D. L. (2018). Measurement theory and applications for the social sciences. Guilford.

Blodgett, C. (2018). Trauma-informed schools and a framework for action. In J. D. Osofsky & B. M. Groves (Eds.), Violence and trauma in the lives of children. (Vol. 2). Praeger.

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quinonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

Brann, K. L., Daniels, B., Chafouleas, S. M., & DiOrio, C. A. (2022). Usability of social, emotional, and behavioral assessments in schools: A systematic review from 2009 to 2019. School Psychology Review, 51(1), 6–24.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

Briesch, A. M., Chafouleas, S. M., Dineen, J. N., McCoach, D. B., & Donaldson, A. (2021). School building administrator reports of screening practices across academic, behavioral, and health domains. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 24, 1–12.

Briesch, A. B., Chafouleas, S. M., & Riley-Tillman, T. C. (2016). Direct behavior rating (DBR): Linking assessment, communication, and intervention. The Guilford Press.

Caemmerer, J. M., Koslouski, J. B., Briesch, A. M., Chafouleas, S. M., Melo, B. (Under review). Looking under the rocks for equity in assessment: The hidden gem of consequential validity.

Cella, D., Blackwell, C. K., & Wakschlag, L. S. (2022). Bringing PROMIS to early childhood: Introduction and qualitative methods for the development of early childhood parent report instruments. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 47(5), 500–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsac027

Chafouleas, S. M., & Iovino, E. A. (2021). Engaging a whole child, school, and community lens in positive education to advance equity in schools. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 758788. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.758788

Cizek, G. J., Bowen, D., & Church, K. (2010). Sources of validity evidence for educational and psychological tests: A follow-up study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(5), 732–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164410379323

Comer, J. P. (2020). Commentary: Relationships, developmental contexts, and the school development program. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1515296

Comer, J. P., Joyner, E. T., & Ben-Avie, M. (Eds.). (2004). Six pathways to healthy child development and academic success: The field guide to Comer Schools in action. Corwin Press.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Getting good qualitative data to improve educational practice. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/educating-whole-child-report

Dever, B. V., Raines, T. C., Dowdy, E., & Hostutler, C. (2016). Addressing disproportionality in special education using a universal screening approach. The Journal of Negro Education, 85(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.85.1.0059

Furlong, M. J., Dowdy, E., & Nylund-Gibson, K. (2018). Social emotional health survey secondary manual. UC Santa Barbara International Center for School-Based Youth Development. www.project-covitality.info/

Goldberg, S.B. (2021). Education in a pandemic: The disparate impacts of COVID-19 on America’s students. U.S. Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/20210608-impacts-of-covid19.pdf

Gottlieb, L. M., Hessler, D., Long, D., Laves, E., Burns, A. R., Amaya, A., Sweeney, P., Schudel, C., & Adler, N. E. (2016). Effects of social needs screening and in-person service navigation on child health: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(11), e162521–e162521. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2521

Hayes, S. C., Nelson, R. O., & Jarrett, R. B. (1987). The treatment utility of assessment: A functional approach to evaluating assessment quality. The American Psychologist, 42(11), 963–974. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.42.11.963

Henrikson, N. B., Blasi, P. R., Dorsey, C. N., Mettert, K. D., Nguyen, M. B., Walsh-Bailey, C., Macuiba, J., Gottlieb, L. M., & Lewis, C. C. (2019). Psychometric and pragmatic properties of social risk screening tools: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(6 Suppl 1), S13–S24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.012

Herman, K. C., & Bonifay, W. (2023). Best practices for examining and reporting the social consequences of educational measures. School Psychology, 38(3), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000550

Iliescu, D., & Greiff, S. (2021). On consequential validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 37(3), 163–166. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000664

Kim, E. K., Anthony, C. J., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2021). Social, emotional, and behavioral assessment within tiered decision-making frameworks: Advancing research through reflections on the past decade. School Psychology Review, 51(5), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1907221

Kim, E. K., & Choe, D. (2022). Universal social, emotional, and behavioral strength and risk screening: Relative predictive validity for students’ subjective well-being in schools. School Psychology Review, 51(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1855062

Kim, E. K., Furlong, M. J., Dowdy, E., & Felix, E. D. (2014). Exploring the relative contributions of the strength and distress components of dual-factor complete mental health screening. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 29(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573514529567

Koslouski, J. B., Chafouleas, S. M., Briesch, A. M., Caemmerer, J. M., Perry, H. Y., Oas, J., Xiong, S. S., & Charamut, N. R. (2024). School-based screening of social determinants of health: A scoping review. School Mental Health, 16(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09622-w

McIntosh, K., & Goodman, S. (2016). Integrated multi-tiered systems of support: Blending RTI and PBIS. Guilford Press.

Meier, J. H. (1975). Screening, assessment, and intervention for young children at developmental risk. In N. Hobbs (Ed.), Issues in the classification of children. (Vol. 2). Jossey-Bass.

Messick, S. (1998). Consequences of test interpretation and use: the fusion of validity and values in psychological assessment. ETS Research Report Series. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.1998.tb01797.x

Miller, F. G., Chafouleas, S. M., Riley-Tillman, T. C., & Fabiano, G. A. (2014). Teacher perceptions of the usability of school-based behavior assessments. Behavioral Disorders, 39, 201–210.

Moore, S., Long, A. C. J., Coyle, S., Cooper, J. M., Mayworm, A. M., Amirazizi, S., Edyburn, K. L., Pannozzo, P., Choe, D., Miller, F. G., Eklund, K., Bohnenkamp, J., Whitcomb, S., Raines, T. C., & Dowdy, E. (2023). A roadmap to equitable school mental health screening. Journal of School Psychology, 96, 57–74.

Naglieri, J. A., LeBuffe, P. A., & Shapiro, V. B. (2011). Devereux Student Strengths Assessment – Mini (DESSA-Mini). Apperson.

Norman, G. (2015). The negative consequences of consequential validity. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 20(3), 575–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9615-z

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Bustamante, R. M., & Nelson, J. A. (2010). Mixed research as a tool for developing quantitative instruments. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(1), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689809355805

Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2020). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650

QSR International. (2023). NVivo 14.

Sankofa, N. L. (2022). Transformativist measurement development methodology: A mixed methods approach to scale construction. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 16(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898211033698

Severson, H. H., Walker, H. M., Hope-Doolittle, J., Kratochwill, T. R., & Gresham, F. M. (2007). Proactive, early screening to detect behaviorally at-risk students: Issues, approaches, emerging innovations, and professional practices. Journal of School Psychology, 45, 193–223.

Simpfenderfer, A., Garnett, B., Smith, L., Moore, M., Sparks, H., Bedinger, L., & Kidde, J. (2023). Development and validation of a multi-domain survey assessing student experiences with school-based restorative practices implementation: Community based participatory research at work for school equity. Contemporary Justice Review, 26(2), 145–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580.2023.2258904

Sokol, R. L., Clift, J., Martínez, J. J., Goodwin, B., Rusnak, C., & Garza, L. (2022). Concordance in adolescent and caregiver report of social determinants of health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 63(5), 708–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.06.004

Starck, J. G., Riddle, T., Sinclair, S., & Warikoo, N. (2020). Teachers are people too: Examining the racial bias of teachers compared to other American adults. Educational Researcher, 49(4), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20912758

Suldo, S. M., & Shaffer, E. J. (2008). Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. School Psychology Review, 37(1), 52–68.

International Organization for Standardization. (2018). The standard definition of usability (ISO9241–11). https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9241:-11:ed-2:v1:en

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2014). Child welfare: Federal agencies can better support state efforts to prevent and respond to sexual abuse by school personnel (GAO-14–42). https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-14-42.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Healthy People 2030: Social determinants of health. Retrieved November 17, 2023 from https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

Ungar, M., & Liebenberg, L. (2011). Assessing resilience across cultures using mixed methods: Construction of the child and youth resilience measure. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 5(2), 126–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689811400607

von der Embse, N., Kilgus, S., Oddleifson, C., Way, J. D., & Welliver, M. (2023). Reconceptualizing social and emotional competence assessment in school settings. Journal of Intelligence, 11(12), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11120217

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants in this study as well as members of the research team who assisted with data collection (Hannah Perry, Natalie Charamut).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Northeastern University Library. The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, the US Department of Education, through Grant R305A220249 to University of Connecticut. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the US Department of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the University of Connecticut’s Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (Study X23-0063).

Consent to Participate