Abstract

Improving child behavior and promoting family well-being is a key objective of evidence-based parenting programs, such as the Triple P–Positive Parenting Program. To achieve this goal, parenting programs are delivered using a multidisciplinary workforce. Previous researchers have collectively examined the entire workforce of parenting practitioners to determine the factors that influence program delivery, primarily using self-report measures. However, these findings did not highlight the unique factors relevant to specific practitioner disciplines. Educators are one practitioner discipline that play an integral role in delivering parenting programs through schools and early childhood learning settings. This study aimed at exploring the facilitators and barriers that impact frequency of program use for educator practitioners using both qualitative and quantitative analyses. Data from 404 Triple P educator practitioners were extracted from a larger dataset of 1202 practitioners from English-speaking countries who completed self-report questionnaires and responded to three open-ended questions. Hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted using eight independent variables (with participant characteristics as control variables), revealing seven positive and one negative predictor for frequency of use. A thematic analysis was then conducted on the qualitative responses, producing 11 themes and 28 subthemes. The quantitative analysis revealed organisational support, perceived usefulness, and practitioner self-regulation were the most important positive predictors. The qualitative analysis supported these findings and revealed novel barriers including Covid-19/work from home, online delivery, parent factors, and specific organisational factors. These findings highlight the need for online resources, reliable virtual delivery methods, improved ways to reach and engage families, and additional trained education practitioners to distribute high workloads.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Evidence-based parenting programs have the potential to benefit children in numerous ways including reducing social, emotional and behavioral problems, mental health problems, and increasing children’s self-esteem, social competence, and school grades (Dretzke et al., 2009; Haggerty et al., 2013; Sanders et al., 2014). Parents and caregivers are also potential beneficiaries, with evidence-based parenting programs facilitating an increase in parenting skills, improved self-efficacy, lower stress, and higher parental satisfaction (Chan et al., 2018; Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008). Although there is growing scientific consensus that parenting programs are effective at influencing positive change (Comer et al., 2013), only a relatively small fraction of parents participate in evidence-based parenting programs globally (Whittaker & Cowley, 2012). To increase the reach and access of parenting programs, a range of strategies is ideally used within a model of support, which includes varying levels of intensity, multiple modalities for delivery, and training a multidisciplinary workforce to deliver across multiple settings (Turner & Sanders, 2006). One well-established parenting program aimed at maximising reach and achieving population-level family outcomes by the use of a public health framework is the Triple P–Positive Parenting Program, which has demonstrated improved family outcomes for a broad range of socioeconomic groups from varying cultures across multiple meta-analyses (e.g., Sanders et al., 2014). Over 100,000 Triple P practitioners from a range of professional backgrounds have been trained in over 58 countries, including psychologists, family workers, social workers, doctors, nurses, clergy, and educators (Sanders & Ralph, 2022).

School is a critical setting to deliver programs fostering the development, learning, and well-being of children. Researchers have consistently demonstrated that when schools and parents work collectively toward goals for children, the subsequent benefits are improved mental health, child adjustment, motivation, achievement, social skills, school attendance, rates of graduation, and successive progression to tertiary education (Barger et al., 2019; Mapp & Kuttner, 2013; Sanders et al., 2021; Sheldon & Epstein, 2004). School-based interventions that involves families have been found to have positive impact on children’s learning and well-being (Sheridan et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2020). Parenting programs are one type of family–school intervention, and educators are one large subsect of parenting practitioners, which includes teachers, early childhood educators, childcare workers, parent liaison officers, and guidance officers (Turner et al., 2011). Educators provide an essential workforce in delivering parenting programs and a unique opportunity to implement parenting programs due to the accessibility of parents through school, the ongoing commitment that school requires, and easy access to premises for face-to-face training (Shapiro et al., 2010). Furthermore, the integration of education and mental health requires that effective schools include and promote the healthy functioning of students, which involves improving social/behavioral outcomes for children and strengthening active parental involvement (Atkins et al., 2010). The provision of parenting programs in school settings could be an important step in fostering the integration of education and mental health. As a central component to the public health framework, school settings also have the potential to reduce the stigma of attending parenting programs by normalising it within the schooling community (Weisenmuller & Hilton, 2021). Recognising the potential of parenting programs at schools, Triple P have trained education practitioners as a substantial cohort within their workforce (Sanders et al., 2021). However, training practitioners does not always translate into actual delivery of programs to parents, as it is common for parenting practitioners to demonstrate low rates of implementation following training (Cooper et al., 2022).

Despite the potential benefits of having trained educators to deliver parenting programs within school settings, the facilitators and barriers for educators delivering parenting programs remain relatively unexplored. A barrier to program delivery is any factor that impedes or hinders program implementation, and a facilitator is any variable that improves or promotes program use. Program sustainment is the continued delivery of program activities and modules at the required intensity for the ongoing achievement of anticipated program and population goals (Shelton et al., 2018). The sustainment of parenting programs has previously been explored by collectively investigating the entire cohort of practitioners; however, these generalised findings potentially overshadow the nuanced facilitators and barriers experienced by educators. Furthermore, educators work in different environments to other parenting practitioners (e.g., clinical psychologists), thus system-level changes influenced by generalised findings may not be practical to implement across the entire cohort and may not address the unique circumstances encountered by educators. Therefore, it is important to uncover how the facilitators and barriers experienced by the general population of practitioners (namely, organisational, program-related, and practitioner factors) apply specifically to educators.

Self-Regulation and Self-Efficacy

Practitioner self-regulation is one facet that has been shown to influence program sustainment (Sanders et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2015). Self-regulation is the degree to which an individual adjusts and controls their own behavior to achieve the desired goals and standards (Karoly, 1993). Based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977), Sanders and Mazzucchelli (2013) introduced a self-regulatory framework including five aspects: self-sufficiency; self-management; personal agency; problem solving; and self-efficacy. It is argued that focusing on a comprehensive self-regulation framework in training can facilitate greater self-regulation skills in practitioners, help practitioners over challenges in program delivery, and ultimately lead to improved program sustainability (Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2013).

Amongst the five self-regulation factors, self-efficacy, an individual’s belief toward their capacity to successfully execute behaviors to achieve a given task (Bandura, 1977), has been heavily researched within multiple sustainability and implementation frameworks, previously being explored independent of the other constructs (Damschroder et al., 2009; Shelton et al., 2018). When focused on parenting programs, self-efficacy has consistently predicted the frequency and sustained program delivery for practitioners in both quantitative and qualitative studies (Sanders et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2012, 2015; Turner et al., 2011). Triple P encourages self-efficacy by utilising active skill’s training to introduce program content and processes with a deliberate focus toward a practitioner’s personal goal setting, self-directed learning, the management of novel parenting challenges, and self-assessment (Turner & Sanders, 2006). Those with higher levels of perceived self-efficacy are expected to be more consistent in their delivery of parenting programs and overcome unexpected training challenges with greater ease. Over a two year period following training, Triple P practitioners higher in self-efficacy demonstrated higher rates of program delivery (Charest & Gagné, 2019).

Overall, Triple P utilises self-regulation as a fundamental component within program development (McWilliam et al., 2016; Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2013). When aimed at parenting support in educational settings, Triple P draws on a model of self-regulation as an organising framework to actively encourage self-regulation from parents through to practitioners (Sanders et al., 2021). Rehearsals, role-playing, and modeling are used during practitioners’ training to foster self-regulation in applying skills to varying situations, following which they are encouraged to deliver training components before completing their accreditation. This training and accreditation process has been shown to cultivate self-regulated, competent professionals as an outcome (Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2022; Sanders et al., 2022). As self-regulation plays a dynamic role in multiple facets of Triple P’s program development and delivery, it is vital to investigate the impact it has on educators’ sustained program implementation.

Organisation-Level Support

Sustained program delivery for educators may also be influenced by other factors present within educational institutions such as organisational support. Aligning with implementation frameworks, the sustained delivery of Triple P programs has previously been shown to increase alongside the amount of support a practitioner believes the organisation has toward the program (Asgary-Eden & Lee, 2011; Hodge et al., 2016; Seng et al., 2006). Exploratory studies using interviews with Triple P practitioners found that organisational barriers impeded program delivery with inadequate support, a lack of integration with existing work responsibilities, and lack of organisational recognition as primary contributors (Prinz et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2012). As these studies utilised minimal prior evidence for predictors of sustained delivery, they are considered preliminary and lay essential groundwork for further research of organisation-level factors. Triple P’s purveyor organisation (Triple P International) is a key contributor in the successful implementation of Triple P by providing support to organisations throughout implementation (McWilliam et al., 2016). Supportive school organisations would ideally provide adequate funding and resources, suitable delivery environments, support staff, plus quality supervision, and practitioner recognition. A study by Côté and Gagné (2020) demonstrated that in supportive organisations, practitioners who initially harbored negative views toward the implementation of Triple P developed more favored perspectives over time and had greater optimism toward program sustainment. Understanding the impact that organisational factors have on educators delivering Triple P is an important step to improve the sustainability of such programs.

Program Effectiveness and Practitioner Characteristics

The perceived effectiveness of Triple P programs has been identified by practitioners as a major influence in their continued delivery (Shapiro et al., 2012). In a series of interviews, practitioners revealed that witnessing behavioral improvements in their clients’ families was a large motivator to continue delivering Triple P (Shapiro et al., 2015). This closely aligns with personal agency, a factor within the self-regulation framework where positive feedback is more likely to accompany higher levels of self-regulation, and thus the client’s success is attributed to the practitioners delivery (Hamilton et al., 2014). The personal values and demographics (including age, gender, education level, and years in the field) of practitioners could also affect sustained program use, reflected in implementation frameworks that frequently include these elements (Aarons et al., 2010; Damschroder et al., 2009; Shelton & Lee, 2019).

Satisfaction with Program Features, Perceived Usefulness, and Perceived Interference

Various findings also suggest that the sustainability of parenting programs can be influenced by a program’s capability to cater to individual client characteristics such as language differences, and behavioral complexity (Breitkreuz et al., 2011; Sanders et al., 2009). Similarly, a program’s adaptability, quality of training resources, and transition from research to practice all have the potential to impact continued delivery (Aarons et al., 2010; Shapiro et al., 2012; Shelton et al., 2018). More specifically, Turner et al. (2011) demonstrated that Triple P was more likely to be delivered by practitioners if they considered it flexible to the varying needs of clients and simple to deliver. Frequency of program delivery was also positively related to how useful practitioners rated Triple P’s self-regulation framework, and how convincing they found the supporting evidence base. However, if Triple P diverges from a practitioner’s preferred theoretical approach, or delivery is perceived to interfere with their personal life, frequency of use has been shown to decrease over time (Sanders et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2015). Overall, research investigating the entire population of practitioners has demonstrated a range of facilitators and barriers that can impact program use extending from the organisations’ input and the perceived effectiveness of programs, right through to individual practitioner factors (such as self-regulation), all of which are yet to be explored within each individual practitioner discipline.

Current Study

The overall aim of this study was to investigate the facilitators and barriers impacting educators in the delivery of Triple P and to determine the relative importance of factors in predicting educators’ frequency of delivery. Uncovering these influences can guide future implementation of Triple P by educators and in school settings to maximise program reach. This study used a subset of data collected from an international online survey sent to all practitioners trained in Triple P over a 25-year period (in English-speaking countries). The approach to survey as many practitioners trained in Triple P as possible was adopted because the aim of the larger study was to provide a comprehensive model of predictors of sustained program use. This approach to survey practitioners trained over a long timeframe expands on previous implementation research, which has usually surveyed practitioners who were recently trained in a program to examine the barriers and facilitators to delivering the program in a short timeframe following training (often 1–2 years; Shelton & Lee, 2019). Surveying practitioners who were trained over a long period of time allows us to see the impact of a broader range of factors that may arise over time. Such findings will provide a more ecologically valid overview of factors affecting long-term sustainability of implementation. Only the data collected from practitioners who were classified as educators was used in the current study. Similar to the larger study, the aim of this study was to provide a comprehensive overview of the all the potential barriers and facilitators to the delivery of Triple P by educators. Accordingly, a quantitative approach to examine the relative importance of all previously identified factors was combined with a qualitative approach exploring educators’ views in more depth, and allowing the identification of additional factors which may play a role.

First, a quantitative approach was used to explore the main research question in this study: What are the facilitators and barriers impacting the program delivery of educators trained to deliver Triple P? Practitioners completed items assessing their current frequency of delivery and a range of measures assessing potential facilitators and barriers identified in previous research, including self-regulation, self-efficacy, organisational, program-related, and additional practitioner factors. It was hypothesised that: frequency of program delivery would be independently positively predicted by all factors measured in the survey, except for perceived interference which would negatively predict frequency of program delivery (after controlling for age, gender, education level, and years in the field).

Second, a qualitative approach was used to explore the facilitators and barriers encountered by educators beyond the boundaries imposed by the predetermined survey. Responses to three open-ended questions were explored using thematic analysis, and then categorised, described, and tallied to across themes and subthemes. The aim of this qualitative analysis was to enable the discovery of independent and supplementary information that could not be extracted using a predetermined list of facilitators and barriers alone (Wolff et al., 1993). The main research questions that were explored in the qualitative data were:

-

1.

What are the factors that educators identify as facilitators and barriers to program delivery in response to open-ended questions?

-

2.

What are the relative frequencies of the factors identified as facilitators and barriers?

Method

Participants

The study formed part of a larger research project collecting data from 1202 Triple P practitioners from various disciplines whose Triple P training was completed between 1997 and 2020 (see Tellegen et al., 2022). Overall, 404 participants were classified as educator practitioners to be included in this study (identified during Triple P training), including teachers, guidance officers, parent liaison officers, childcare workers, and school psychologists. The cohort identified as 93.6% female, 5.4% male, and 1% did not disclose gender. Most practitioners were aged between 35 and 64 years, and training was mainly completed in the USA (39.6%), United Kingdom (25.7%), Canada (20.8%), or Australia (9.4%). A bachelor’s degree or higher had been attained by 58.4% of participants and 40.4% completed some tertiary level study. The training was completed by 66.1% of participants between 2016 and 2020. No Triple P sessions were delivered by 16.6% of participants over the previous six months, and greater than 20 sessions were delivered by 18.3%. See Table 1 for detailed information.

Procedure

In May 2021, an invitation to complete a 10-min online survey (administered on UQ’s Qualtrics platform) was sent from Triple P International to all Triple P practitioners trained in English-speaking countries. The emails were distributed to 28,789 practitioners, subsequently opened by 13,371, and 2663 started the survey. Two email reminders were sent one per week in the two weeks following the initial email, with data collection being completed in a 4-week period.

Measures

Five sections were included in the current study: demographic measures, a survey on program use, self-regulation and self-efficacy measures, the facilitators and barriers checklist, and a brief open-ended questionnaire.

Frequency of Program Use

Frequency of program use was measured with one question adapted from previous Triple P implementation studies, “Making an estimation, about how many sessions of Triple P did you deliver in the last six months?,” rated on an 8-point scale (see Table 1). Eight different response options were provided on an ordinal scale to help practitioners to estimate the number of sessions: 0 sessions, 1–2 sessions, 3–5 sessions, 6–9 sessions, 10–19 sessions, 20–29 sessions, 30–39 sessions, and more than 40 sessions.

Self-Efficacy

The practitioner confidence subscale of the parent consultation skills checklist (PCSC; Turner & Sanders, 1996) was used to assess participants’ current self-efficacy with two items: “How confident are you in conducting parent consultations about child behaviour?” and “Do you feel adequately trained to conduct parent consultations about child behaviour?.” Items were rated on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all proficient) to 7 (extremely proficient, no assistance required). An overall score was created by averaging the two items, with higher scores revealing high-self efficacy. The scale indicated good to excellent internal consistency (α = 0.92).

Self-Regulation

The practitioner version of the parenting self-regulation scale (PSRS-Practitioner; Sanders et al., 2017) was used to measure participants’ current self-regulation. A Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) is used to rate each of the 12 items assessed in the PSRS-Practitioner. The scale has a single-factor structure (Tellegen et al., 2022), and excellent internal consistency was demonstrated in the current study (α = 0.95). A sample item was “I feel confident that I can take actions to help parents improve their parenting behaviour.” All items were positively worded, and the total scale was calculated as the average of all 12 items. Higher self-regulation in delivering Triple P was reflected by higher scores.

Facilitators and Barriers of Sustained Program Use

A 39-item questionnaire called the Facilitators and Barriers Checklist (FBC), created for larger research project (Ma et al., 2023a; b) which collected the data used in this study, was used to measure the facilitators and barriers that could impact educators’ sustained program use. The FBC contained six subscales: organisational support (14 items; e.g., “My organisation is supportive of professional development around Triple P”), value propensity (6 items; e.g., “I strongly believe positive parenting programs should seek to create child-, parent-, and family-friendly communities”), perceived usefulness (6 items; e.g., “I receive positive feedback from parents regarding the program”), perceived interference (6 items; e.g., “After hours appointments clash with my other commitments”), satisfaction with program features (4 items; e.g., “I think Triple P parent and practitioner materials are helpful”), and session management ability (3 items; e.g. “I tend to set specific goals/agendas for sessions”). Each subscale demonstrated an internal consistency ranging from acceptable to excellent (α = 0.95, 0.93, 0.85, 0.76, 0.84, and 0.80, respectively). Positive coding was used for all items, except in the program interference subscale. The total score for each subscale was calculated by averaging the items.

Open-Ended Facilitator and Barrier Questions

Three open-ended questions were used to qualitatively assess facilitators and barriers for educators delivering Triple P. “Q1: Based on your experience, what has helped you the most in being able to deliver Triple P programs to parents?,” “Q2: What has made it hard for you to be able to deliver Triple P programs to parents?,” and “Q3: What would make it easier for you to deliver Triple P programs?.”

Identifying Facilitators and Barriers

Thematic analysis was used to identify the types of facilitators and barriers that educators experience in delivering programs in response to the open-ended questions. Thematic analysis is the most common method used to analyze open-ended or qualitative responses, as it enables the identification of recurrent and noteworthy patterns within the data pertaining to the research question (Braun & Clarke, 2006). More specifically, this study used codebook thematic analysis, which is best suited toward the creation of themes and categories from the content of data, as opposed to other methods such as reflexive thematic analysis where themes are created preceding the study based on prior research (Braun & Clarke, 2021). The aim was to provide an objective and reliable summary of the answers to the qualitative questions (without postulating what the answers may be a priori) that could be recognised by any researcher reviewing the data. Therefore, the codebook thematic analysis as opposed to reflexive thematic analysis suited the aims of the study best, where the codes could be generated from the data and an inter-rater reliability calculated. The participants’ responses were initially analyzed by three reviewers: an honors student (first author), Ph.D. level academic (second author), and a Ph.D. student (third author). Initial labels (codes) were developed individually by each reviewer after working through all the responses individually. Following this, a meeting between the three reviewers led to the creation of the codebook: a final list of themes (capturing broader meaning) and subthemes (capturing specific meaning). After reviewing the 11 themes and 28 subthemes (see Table 2) for simplicity and coherence we defined and named them.

Coding Facilitators and Barriers

The qualitative dataset contained 124 participants (31%) who did not respond to any of the three questions and were removed prior to coding, leaving data from 280 participants who responded to at least one of the three questions (Question 1: n = 254; Question 2: n = 264, Question 3: n = 228). The first and second authors then independently used the codebook of themes/subthemes to code all the responses from practitioners for each question, allowing for multiple codes to be allocated for each response. The inter-rater reliability for each of the three questions demonstrated “substantial” to “almost perfect agreement” (McHugh, 2012); Q1: k = 0.81, p < 0.001; Q2: k = 0.81, p < 0.001; Q3: k = 0.80, p < 0.001.

Analysis

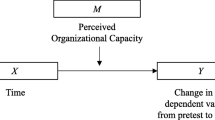

Assumption checks were completed prior to regression analysis. Hierarchical multiple regressions (HMRs) were conducted on the eight focal variables to investigate their independent ability to predict frequency of program use. Control factors were included in block 1 for each regression. Separate HMRs were conducted to ensure the variance explained by each factor for frequency of program use was accurately represented, such that no variability was consumed by the remaining factors. A thematic analysis was then completed to explore common themes for responses to the three qualitative questions. The responses were coded by two independent reviewers, using Microsoft Excel. Following this, an inter-rater reliability analysis using Kappa statistics was conducted. The two coders reviewed the misaligned responses and reached a consensus on agreed codes, and the percentage of responses for each theme were calculated.

Results

Data Cleaning and Missing Data Analysis

A missing data analysis determined that all participants were considered adequately assessed against the conventional threshold of 50%, as a maximum of 17 out of 54 variables in the quantitative data was missing for any one participant (Schlomer et al., 2010). Approximately 77% of participants had no missing data, and greater than 98% were missing less than 10% data. In total, seven participants were removed from the analysis as they did not contain values for either age, gender, or education level. A missing values analysis revealed a nonsignificant Little’s MCAR test, χ2(2216, N = 404) = 2274.24, p = 0.190, suggesting no systematic patterning was present, and the missing data were missing completely at random (Bennett, 2001). The missing data for continuous variables were then estimated with the expectation–maximisation algorithm (Bennett, 2001). To investigate the impact of the outliers, all regression analyses were conducted both with and without the identified outliers. The outcomes indicated no change in the significance of the results; therefore, the analysis was subsequently reported with the outliers included. The descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between study variables are displayed in Table 3. No relationships between variables exceeded the conventional threshold r = .80, indicating no bivariate multicollinearity.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression (HMR)

Eight HMR analyses were conducted to determine the independent predictive effects of self-efficacy, self-regulation, organisational support, value propensity, perceived usefulness, perceived interference, satisfaction with program features, and session management ability on frequency of program use after controlling for age, gender, education level, and years in the field. At block 1 for each HMR, age, gender, education level, and years in the field explained no significant variance in frequency of program use scores. Refer to Table 4 for detailed statistics.

All variables in block 2 of the eight separate HMRs explained significant variance in frequency of program use scores. In total, seven variables were positive predictors, with their relative importance and amount of explained variance in the following order: organisational support explained 16% (β = 0.41), perceived usefulness explained 11% (β = 0.34), self-regulation explained 11% (β = 0.33), session management ability explained 8% (β = 0.29), self-efficacy explained 6% (β = 0.25), satisfaction with program features explained 4% (β = 0.21), and value propensity explained 1% (β = 0.11). The only negative predictor was perceived interference (β = − 0.13), which explained 2% of the variance and was slightly more important than value propensity.

Thematic Analysis

The frequency of each facilitator and barrier for the three questions as indicated by educator practitioners can be seen in Table 5. In response to question one, indicating the facilitators for delivering Triple P programs, the themes with the highest percentage of responses were support (23.1%), resources (21.6%), and practitioner factors (11.1%). More specifically, the dominant subthemes emerging from those areas included support from their “organisation/team/peers” (18.4%). Educators continually outlined that being surrounded by a team that encourages the use of Triple P makes it much easier to deliver, illustrated through responses such as, “Good support from other Triple P practitioners and a supervisor who understands the importance of the program.” The quality and availability of “general resources” (16.9%) were the second most frequently mentioned, where educators acknowledged the workbooks and presentations as fundamental to facilitating delivery, e.g., “the book and materials are well laid out to deliver Triple P.” Further to this, educators frequently indicated the participant tip sheets were particularly valuable, e.g. “The tip sheets are very useful. There is a wide variety of topics that are age specific. They are easy to read, and the information is broken down which is very helpful for parents.” Finally, “practice delivering” (4.2%) and “practitioners’ confidence” (2.4%) were also described as influential in facilitating the delivery of Triple P. educators indicated that repeated exposure to the material improved their understanding and application of the content which facilitated further delivery, e.g., “Continually presenting the material to new groups of parents” and “The program has become increasingly familiar, and I can see how much my confidence has increased.”

In response to question two, outlining the barriers impacting the delivery of Triple P programs, the themes with the highest percentage of responses were: parent factors (22.9%), practical issues (16.3%), and Covid-19/work from home (15.2%). Within these themes, the predominant subthemes that emerged for parent factors were “engaging parents” (9.5%) and “reaching families” (6.6%). Educators outlined that a lack of commitment was an issue for parents throughout the program, e.g., “Another obstacle we deal with is parents who don't commit or commit but then don't show up!.” It also appeared that transportation issues frequently impacted the ability to reach parents, e.g. “Those without means of travel can struggle to access.” Within practical issues, the prevailing subthemes were both “workload/time issues” (7.7%) and “organisational space/facilities” (4.1%). Educators frequently indicated that they already had high workloads and fitting Triple P delivery into their schedules was challenging, e.g. “It is time consuming to deliver Triple P on top of our job responsibilities.” Further to this, it was repeatedly identified that a lack of defined workspaces (e.g., working from the client’s home, or lack of space at work) impacted their ability to deliver, e.g. “There is no identified space set aside to give trainings” or “It’s difficult to find a centralised location that all parents can access.” Finally, Covid-19 and working from home were recognised as creating barriers to delivery through difficulty with, or a lack of access to technology, plus an inability to meet face-to-face, e.g. “During the pandemic it has been difficult to reach families at risk due to lack of proper electronical devices” and “Covid has made it more difficult as we can't deliver in person.”

In response to question three, indicating what would make it easier for educators to deliver Triple P programs, the themes with the highest percentage of responses were: resources (21.8%), support (12.6%), and practical issues (12.3%). The subtheme responses revealed more specific insights, outlining that educators believed certain improvements to the quality and availability of general resources (14%) would enable easier delivery. It was frequently expressed that converting to digital tip sheets, and workbooks was highly desirable amongst the cohort, with responses such as “Have access to tip sheets electronically” and “Digital forms including tip sheets, it is hard to send paperwork to families to fill out and get it back.” Further to this, it was repeatably outlined that the parent video resources (7.8%), such as DVDs, could be converted to online, e.g. “For parents to have access to the video online.” Educators also focused on how “organisation/team/peer support” (9.6%) could be improved by conveying their desire for additional Triple P staff to be trained at their organisation and integration within the team, e.g. “If the school division had staff members trained and it was recognized and supported through my school division” and “Having co-workers get trained as well.” Finally, the responses also revealed that workload/time issues (5.5%) could be optimised by having dedicated periods provided in their role to specifically deliver Triple P and less work commitments overall, e.g., “Allocated time to deliver the program within my own organisation” and “Decreased caseload in schools.”

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first study using an international sample of practitioners to explore the facilitators and barriers impacting educators’ implementation of a parenting program, specifically Triple P. As hypothesised, all factors measured in the quantitative analysis independently positively predicted the frequency of Triple P program use (after controlling for age, gender, education level, and years in the field), except for perceived interference which was a negative predictor. Moreover, as expected, due to the extraction of this data from the whole population of practitioners, the relative importance of all positive and negative predictors for educators was consistent with previous research containing all practitioner disciplines (Ma et al., 2023a; b). Many of these factors were also identified with a high percentage of responses from a thematic analysis, which further revealed additional novel themes (including parent factors, Covid-19/work from home, and online delivery) that were previously unidentified.

The strongest independent predictor of program use for educators was organisational support. This aligns with previous research (Asgary-Eden & Lee, 2011; Seng et al., 2006), such that greater perceived support from an educator’s organisation, both proactive and responsive, predicted increased delivery of Triple P. The thematic analysis aligned with this and further reinforced previous exploratory findings (Prinz et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2012), where the subtheme of “organisational/team/peer support” demonstrated the highest percentage of responses across all facilitator themes. Educators frequently stated that having a team around them who actively recognised and encouraged the use of Triple P promoted greater use. Further to this, when asked what would make it easier to deliver Triple P, educators principally outlined that increasing the number of trained practitioners within their school would help. This highlights the importance of an integrated network of Triple P practitioners within the school environment who can distribute the demand for parenting interventions and help problem-solve unique parenting challenges. Collaboration from the purveyor organisation is critical for implementation through early phases and on-going maintenance (McWilliam et al., 2016), in addition to partnerships with program developers and researchers to disseminate training information (Hodge et al., 2016; McWilliam et al., 2016). It is important to consider that the organisational support toward a parenting program could be influenced by the school’s current policies and practices around parent engagement and the integration of mental health and parenting practices. However, school organisations also appear to require greater internal cooperation to ease unsustainable workloads that impede consistent delivery.

Perceived usefulness was the second strongest independent positive predictor of program use. This aligns with previous quantitative findings (Turner et al., 2011) and interview-style research (Shapiro et al., 2015), where practitioners outlined that observing the progressive behavioral improvements of Triple P clients encouraged delivery. This belief about usefulness could be influenced by the response received from parents, which reflects the levels of parent engagement and whether the program is aligned to the local family culture. The thematic analysis also revealed this finding with a small number of responses outlining “beliefs in effectiveness” as a facilitator to delivery; however, it was not a dominant subtheme. This difference in magnitude could be attributed to the specific questions in the FBC and the thorough interview style that previous research implemented (using follow-up questions), compared to the single open-ended facilitator question that participants responded to qualitatively. Overall, educators perceived usefulness does facilitate delivery; however, when given an opportunity to broadly elaborate on facilitators, they appeared to focus on other elements that are more practically relevant.

As anticipated, the relative strength of perceived usefulness was very similar to self-regulation, which includes the characteristic of personal agency (Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2013), and similar to perceived usefulness, attributes positive client feedback to practitioners delivery (Hamilton et al., 2014). In addition to self-regulation, higher self-efficacy was also related to increased delivery, concurring with previous research that identified self-efficacy as positively predicting program use (Charest & Gagné, 2019; Sanders et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2012). The qualitative responses extended these findings by indicating “practitioner factors” (including “practitioner confidence”) as a common answer for facilitating Triple P delivery, which also aligns with previous interview responses by practitioners (Shapiro et al., 2015). Resembling a close relation to self-efficacy and aligning with previous research on similar items (Shapiro et al., 2012), session management ability also positively predicted frequency of use. Collectively, these outcomes confirm the inclusion of a comprehensive self-regulation model as a fundamental component within program development for Triple P (McWilliam et al., 2016; Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2013). The ability for educators to overcome novel parenting challenges, keep parents on track, adapt skills beyond their initial scope, and self-evaluate, all influence how regularly they deliver programs. Therefore, the procedures shown to foster self-regulation skills during the training and accreditation process (Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2022; Sanders et al., 2022), to support multiple facets of Triple P delivery, are well directed to encourage frequent delivery for educators.

Frequency of use was also positively predicted by satisfaction with program features, which incorporates factors commonly included in implementation frameworks such as the quality of materials, training flexibility, and conversion from research to practice (Aarons et al., 2010; Shelton et al., 2018). However, the relative importance of this variable was low when compared to the high proportion of responses for “resources” as a facilitator in the thematic analysis. This difference is likely due to the limited number of items (one) regarding resources in the FBC. When able to provide further detail, educators consistently outlined that the availability and quality of resources facilitated program delivery, specifically indicating that tip sheets, workbooks, presentations, and videos greatly assist in conveying concepts and techniques to parents. Furthermore, as highlighted in previous research (Shapiro et al., 2012), in circumstances where issues with the quality and availability of resources were present, they acted as a barrier to delivery. Some commonly mentioned difficulties include resources being predominately hard copy (such as physical books, worksheets, and DVDs), which makes it challenging to distribute for participants use. Future research should address this by modifying resources for virtual use (e.g., electronic tip sheets and online modules) and determining the impact this has on delivery for educators. Due to the quantitative and qualitative consensus on the availability and quality of resources, it is essential that educators are provided with continually updated material that can be supported across a variety of platforms to facilitate increased delivery.

Another positive predictor for frequency of use was the degree to which educators endorsed the values central to Triple P (Sanders, 2008). This corroborates the inclusion of practitioner values and principles integrated within various implementation frameworks (Aarons et al., 2010; Damschroder et al., 2009; Shelton & Lee, 2019). This theme did not appear in the qualitative responses. However, the benefit of agreeing with the core values of Triple P is a particularly nuanced idea that may not be considered unless specifically prompted by a precise question (as in the FBC). Future research can explore this further by conducting qualitative interview style focus groups which specifically ask educators about the impact that the values of the parenting program have on their ability to deliver.

Lastly, in line with prior research (Sanders et al., 2009; Shapiro et al., 2015), the more educators believed Triple P delivery interfered with their work commitments, personal schedule, or ideal theoretical approach, the less they tended to deliver. However, the relative importance of perceived interference was quite low compared to the proportion of responses for “practical issues” (including “workload/time issues”), which was the second highest barrier identified in the qualitative analysis. When given an opportunity to elaborate, educators commonly indicated that their high caseloads made it challenging to fit in Triple P delivery, alongside neatly orchestrating sessions with parents’ conflicting schedules. This further highlights the importance of having additional parenting practitioners trained within school settings (Sanders et al., 2021). Additionally, educators’ roles could be modified so they can solely focus on program delivery, alleviating their work demands across multiple commitments. It also presents an opportunity for Triple P International to assist schools in creating routine timetables for program delivery, so parents can adjust their schedules to fit reliable session times.

In addition to providing similar responses to the quantitative variables, the qualitative analysis also addressed the aim of discovering independent novel facilitators and barriers, including “parent factors,” “Covid-19/work from home,” and “online delivery.” The novel barrier exhibiting the greatest proportion of responses was “parent factors,” with educators outlining the difficulty they encountered both reaching and engaging parents. This was unique compared to the FBC, as no variables directly explored these two areas. An inability to reach parents included an absence of program awareness, in addition to a lack of initial commitment to attend. These findings suggest that current Triple P advertising is not sufficiently engaging the intended demographic. As such, future research should explore alternative marketing strategies including social media, which has been shown to increase the utilisation of mental health services (Booth et al., 2018; Mehmet et al., 2020). The inability to engage families was represented through reports of high program attrition, which is also evident in previous research (Barrett, 2010). A lack of reaching and engaging parents could be attributed to the stigma associated with parenting interventions, or parents failing to sustain program commitments with their busy schedules (Mytton et al., 2014). Programs delivered through educational settings may also be prone to experiencing difficulties with parent engagement and involvement, which are common barriers experienced in the delivery of family–school interventions (Daniel, 2011). One potential remedy to these barriers are online platforms that enable discrete self-paced learning, which has been shown to engage families for sufficient program lengths of typically greater than four sessions (Day et al., 2021). However, further research is still needed into the reasons for low commitment and high program attrition through schools.

The discovery of two other novel themes included “Covid-19/work from home” and “online delivery.” These items were not identified in the FBC; however, their appearance is not surprising given the widespread disruption that was caused to mental health services during Covid-19 (Xiong et al., 2020). Substantial overlap was evident for these two barriers, as the isolation of working from home during the Covid-19 increased the reliance for online delivery (Feijt et al., 2020; Mahoney et al., 2021). Educators indicated that the Covid-19 pandemic severely impacted their ability to access families to deliver training. Furthermore, due to the increased use of virtual delivery, several difficulties were reported including interruptions due to poor Internet connections and the practitioners or parents lack of experience using virtual conferencing. In addition to this, educators repeated concerns regarding complications with providing parents course materials, as most resources require physical access with no electronic versions available. Moving beyond Covid-19, these responses indicate the importance for Triple P to modify their program resources for electronic access to accommodate the growth in popularity of online treatment (Bierbooms et al., 2020). At present, it appears the online platforms utilised by Triple P educator practitioners are not sufficient to meet the current curriculum provided. However, digital training spaces that are user-friendly offer a convenient platform for parents to complete training from their home, access written and visual materials, and enable practitioners the ability to schedule training times that are more convenient for both parties (Alqahtani & Orji, 2020). Furthermore, self-paced online programs can be supplemented with a lower number of virtual practitioner sessions, which offers a viable solution to decreasing the commitment of educators and alleviate their increased work demands. These changes will likely be met with new challenges, such as copyright issues and a need to conduct additional research validating the efficacy of parenting programs when delivered online, however initial studies appear promising (Prinz et al., 2022; Spencer et al., 2020). Overall, it appears necessary for evidence-based parenting programs to explore the modification of their capabilities to provide reliable online delivery.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study was combining the quantitative analysis with an in-depth qualitative investigation. Using open-ended questions provided an opportunity to identify novel facilitators and barriers experienced by educators, in addition to demonstrating the similarity of reported themes with preestablished variables (Wolff et al., 1993). Further to this, the data were gathered from participants who completed their initial Triple P training across a wide time period from 1997 and 2020 in various English-speaking countries. This expands on previous research that used assessments from a single location with relatively brief measurement lengths, failing to capture varying implementation periods (Shelton & Lee, 2019). Thus, the current study design increased internal validity, balancing robustness, and feasibility by more accurately representing educators across varying implementation phases. This more accurately reflects the dynamic capacity of program sustainability, which potentially fluctuates over time alongside the relative importance of factors (Stirman et al., 2012). Additionally, external validity was also enhanced as the findings incorporate the varying educator disciplines across multiple regions, instead of being constrained to a single location or school. However, it should be noted that a more focused approach to data collection where the timeframe, location or participant roles were limited, could be used to provide more rich and nuanced information about the delivery experiences of particular groups.

One limitation of the study was basing the qualitative exploration solely on three open-ended questions that were not followed up with additional questions. While the initial participants responses are valuable, interviews or focus groups would provide more comprehensive and in depth information (Shapiro et al., 2015). The data were a subset taken from a larger project where 28,789 practitioners trained in Triple P were initially emailed and only about 5.6% of these provided data in the survey. A low response rate was expected given that practitioners had been trained over a 25-year period meaning many would have changed roles/email addresses, which is reflected by only 46% opening the initial email. Furthermore, candidates were not provided any incentives to participate in the study. The low response rate means the results should be interpreted with caution as they may not be representative of the population of educators trained in Triple P. educators who completed the survey may have been motivated by polarised views (both positive and negative) toward Triple P. The outcomes, therefore, may be less representative of educators with neutral views toward Triple P which could limit the generalisability of the findings. There are also multiple considerations that potentially influenced the accuracy for frequency of use. Due to the inclusion of participants from wide-reaching locations, it was practical to use self-report measures; however, these outcomes are inherently more vulnerable to response bias (van de Mortel, 2008). As such, participants may have reported answers that present a favorable image of themselves, creating an inaccuracy between the true and self-reported values. Furthermore, as participants reported retrospective frequency of use, their responses may not be precise for the true rate of delivery. Future research should use objective measures (such as case reports and rebate records) to ensure that accurate representations for frequency of use are achieved. The unusual disruption and isolation associated with the Covid-19 pandemic also potentially influenced the reported values for frequency of use, being less indicative of normal circumstances. Finally, as educators are the first subset of practitioners to be independently explored from the larger dataset, until future research is conducted, the qualitative outcomes cannot be compared to other practitioner disciplines to determine how unique educators are regarding the facilitators and barriers they encounter.

Conclusion

This study used multiple methods to explore the facilitators and barriers both aligning with, and unique to, quantitative findings impacting educator practitioners’ frequency of use for delivering Triple P. Overall, five key findings emerged. First, practitioner traits such as self-regulation, self-efficacy, and session management ability were all identified as facilitators through both quantitative and qualitative analysis, validating the use of self-regulation frameworks at the core of evidence-based parenting programs. Second, Covid-19 made it challenging for educators to access clients, increasing their reliance for online delivery. This revealed many limitations to Triple P’s current online capabilities, such as challenges with virtual sessions and incompatibilities due to existing course material being predominantly physical. This highlights the need for improved online delivery methods and modifying course material to electronic mediums. Future research is also required into the efficacy of delivering Triple P online, as opposed to the current research base primarily focused on in-person delivery (Sanders et al., 2014). Third, many educators revealed they are overcommitted in their current organisation with no time to deliver Triple P. Moreover, there was a robust consensus between both quantitative and qualitative responses that organisational support was the strongest facilitator for frequency of program use. As such, training additional educators is ideal to ensure the integrated teams can effectively support and distribute workloads. Reliable online platforms could also assist by enabling educators the ability to schedule and deliver fewer sessions with greater convenience for both practitioners and parents. Fourth, educators identified challenges with reaching and engaging parents. This requires further research into increasing awareness for Triple P (e.g., social media), in addition to investigating parental reasons for commitment hesitancy and high program attrition. Fifth, future research should incorporate additional items in the FBC and complete focus group interviews to further explore the novel facilitators and barriers that emerged as highly relevant in qualitative responses, such as parent factors, practical issues, and online delivery.

References

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2010). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

Alqahtani, F., & Orji, R. (2020). Insights from user reviews to improve mental health apps. Health Informatics Journal, 26(3), 2042–2066. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458219896492

Asgary-Eden, V., & Lee, C. M. (2011). Implementing an evidence-based parenting program in community gencies: What helps and what gets in the way? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39, 478–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0371-y

Atkins, M. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Kutash, K., et al. (2010). Toward the Integration of Education and Mental Health in Schools. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 37, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0299-7

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Barger, M. M., Kim, E. M., Kuncel, N. R., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2019). The relation between parents’ involvement in children’s schooling and children’s adjustment: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 145(9), 855. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000201

Barrett, H. (2010). The delivery of parent skills training programmes. Meta-Analytic Studies and Systematic Reviews of What Works Best. London: Family and Parenting Institute. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9

Bennett, D. A. (2001). How can I deal with missing data in my study? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(5), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00294.x

Bierbooms, J. J. P. A., van Haaren, M., Ijsselsteijn, W. A., de Kort, Y. A. W., Feijt, M. A., & Bongers, I. M. B. (2020). Integration of online treatment into the “new normal" in mental health care in post-COVID-19 times: Exploratory qualitative study. JMIR Formative Research, 4(10), e21344–e21344. https://doi.org/10.2196/21344

Booth, R. G., Allen, B. N., Jenkyn, K. M. B., Li, L., & Shariff, S. Z. (2018). Youth mental health services utilization rates after a large-scale social media campaign: Population-based interrupted time-series analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 5(2), e27–e27. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.8808

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Breitkreuz, R., McConnell, D., Savage, A., & Hamilton, A. (2011). Integrating Triple P into existing family support services: A case study on program implementation. Prevention Science, 12(4), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0233-6

Chan, K. L., Chen, M., Lo, K. M. C., Chen, Q., Kelley, S. J., & Ip, P. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions for grandparents raising grandchildren: A meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(6), 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731518798470

Charest, É., & Gagné, M.-H. (2019). Measuring and predicting service providers’ use of an evidence-based parenting program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(4), 542–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00934-1

Comer, J. S., Chow, C., Chan, P. T., Cooper-Vince, C., & Wilson, L. A. (2013). Psychosocial treatment efficacy for disruptive behavior problems in very young children: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.10.001

Cooper, J., Dermentzis, J., Loftus, H., Sahle, B. W., Reavley, N., & Jorm, A. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of parenting programs in real-world settings: A qualitative systematic review. Mental Health and Prevention, 26, 200236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2022.200236

Côté, M.-K., & Gagné, M.-H. (2020). Changes in practitioners’ attitudes, perceived training needs and self-efficacy over the implementation process of an evidence-based parenting program. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05939-3

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

Daniel, G. (2011). Family-school partnerships: Towards sustainable pedagogical practice. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39(2), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2011.560651

Day, J. J., Baker, S., Dittman, C. K., Franke, N., Hinton, S., Love, S., Sanders, M. R., & Turner, K. M. T. (2021). Predicting positive outcomes and successful completion in an online parenting program for parents of children with disruptive behavior: An integrated data analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 146, 103951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103951

Dretzke, J., Davenport, C., Frew, E., Barlow, J., Stewart-Brown, S., Bayliss, S., Taylor, R. S., Sandercock, J., & Hyde, C. (2009). The clinical effectiveness of different parenting programmes for children with conduct problems: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00987_6.x

Feijt, M. A., de Kort, Y. A. W., Bongers, I. M. B., Bierbooms, J. J. P. A., Westerink, J. H. D. M., & Ijsselsteijn, W. A. (2020). Mental health care goes online: Practitioners’ experiences of providing mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 23(12), 86–864. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0370

Haggerty, K. P., McGlynn-Wright, A., & Klima, T. (2013). Promising parenting programmes for reducing adolescent problem behaviours. Journal of Children’s Services, 8(4), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-04-2013-0016

Hamilton, V. E., Matthews, J. M., & Crawford, S. B. (2014). Development and preliminary validation of a parenting self-regulation scale: “Me as a Parent.” Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(10), 2853–2864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0089-z

Hodge, L. M., Turner, K. M. T., Sanders, M. R., & Filus, A. (2016). Sustained implementation support scale: Validation of a measure of program characteristics and workplace functioning for sustained program implementation. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 44(3), 442–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-016-9505-z

Karoly, P. (1993). Mechanisms of self-regulation: A systems view. Annual Review of Psychology, 44(1), 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000323

Ma, T., Tellegen, C. L., & Sanders, M. R. (2023a). Predictors of program advocacy behaviours in an evidence-based parenting program: A structural equation modelling approach. American Journal of Community Psychology, 71(1–2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12623

Ma, T., Tellegen, C. L., McWilliam, J., & Sanders, M. R. (2023b). Predicting the sustained implementation of an evidence-based parenting program: A structural equation modelling approach. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 50(1), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01226-x

Mahoney, A. E. J., Elders, A., Li, I., David, C., Haskelberg, H., Guiney, H., & Millard, M. (2021). A tale of two countries: Increased uptake of digital mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia and New Zealand. Internet Interventions: THe Application of Information Technology in Mental and Behavioural Health, 25, 100439–100439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100439

Mapp, K. L., & Kuttner, P. J. (2013). Partners in education: A dual capacity-building framework for family-school partnerships. SEDL.

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2012.031

McWilliam, J., Brown, J., Sanders, M. R., & Jones, L. (2016). The Triple P implementation framework: The role of purveyors in the implementation and sustainability of evidence-based programs. Prevention Science, 17(5), 636–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0661-4

Mehmet, M., Roberts, R., & Nayeem, T. (2020). Using digital and social media for health promotion: A social marketing approach for addressing co-morbid physical and mental health. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 28(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12589

Mytton, J., Ingram, J., Manns, S., & Thomas, J. (2014). Facilitators and barriers to engagement in parenting programs: A qualitative systematic review. Health Education and Behavior, 41(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113485755

Nowak, C., & Heinrichs, N. (2008). A comprehensive meta-analysis of Triple P-positive parenting program using hierarchical linear modeling: Effectiveness and moderating variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11(3), 114–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-008-0033-0

Prinz, R. J., Metzler, C. W., Sanders, M. R., Rusby, J. C., & Cai, C. (2022). Online-delivered parenting intervention for young children with disruptive behavior problems: A non-inferiority trial focused on child and parent outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13426

Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. triple P system population trial. Prevention Science, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-009-0123-3

Sanders, M., Hoang, N., Gerrish, R., Ralph, A., & McWilliam, J. (2022). A largescale evaluation of a system of professional training for the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: Effects of practitioner characteristics, type of training, country location and mode of delivery on practitioner outcomes. Manuscript Submitted for Publication.

Sanders, M. R. (2008). Triple P-positive parenting program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(3), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.506

Sanders, M. R., Healy, K. L., Hodges, J., & Kirby, G. (2021). Delivering evidence-based parenting support in educational settings. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2021.21

Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Day, J. J. (2014). The triple P-positive parenting program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(4), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003

Sanders, M. R., & Mazzucchelli, T. G. (2013). The promotion of self-regulation through parenting interventions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0129-z

Sanders, M. R., & Mazzucchelli, T. G. (2022). Mechanisms of change in population-based parenting interventions for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2025598

Sanders, M. R., Mazzucchelli, T. G., Day, J. J., & Hodges, J. (2017). Parenting self-regulation scales. The University of Queensland.

Sanders, M. R., Prinz, R. J., & Shapiro, C. J. (2009). Predicting utilization of evidence-based parenting interventions with organizational, service-provider and client variables. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0205-3

Sanders, M. R., & Ralph, A. (2022). Participant notes for train the triple P-positive parenting program trainer. Brisbane: Triple P International.

Seng, A. C., Prinz, R. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). The role of training variables in effective dissemination of evidence-based parenting interventions. The International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 8(4), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2006.9721748

Schlomer, G. L., Bauman, S., & Card, N. A. (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 1.

Shapiro, C. J., Prinz, R. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2010). Population-based provider engagement in delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions: Challenges and solutions. Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(4), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-010-0210-z

Shapiro, C. J., Prinz, R. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2012). Facilitators and barriers to implementation of an evidence-based parenting intervention to prevent child maltreatment: The Triple P-positive parenting program. Child Maltreatment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511424774

Shapiro, C. J., Prinz, R. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2015). Sustaining use of an evidence-based parenting intervention: Practitioner perspectives. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(6), 1615–1624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9965-9

Sheldon, S. B., & Epstein, J. L. (2004). Getting students to school: Using family and community involvement to reduce chronic absenteeism. School Community Journal, 14(2), 39–56.

Shelton, R. C., Cooper, B. R., & Stirman, S. W. (2018). The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annual Review of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014731

Shelton, R. C., & Lee, M. (2019). Sustaining evidence-based interventions and policies: Recent innovations and future directions in implementation science. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S2), S132–S134. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304913

Sheridan, S. M., Smith, T. E., Moorman Kim, E., Beretvas, S. N., & Park, S. (2019). A meta-analysis of family-school interventions and children’s social-emotional functioning: Moderators and components of efficacy. Review of Educational Research, 89(2), 296–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318825437

Smith, T. E., Sheridan, S. M., Kim, E. M., Park, S., & Beretvas, S. N. (2020). The effects of family-school partnership interventions on academic and social-emotional functioning: A meta-analysis exploring what works for whom. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 511–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09509-w

Spencer, C. M., Topham, G. L., & King, E. L. (2020). Do online parenting programs create change?: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000605

Stirman, S., Kimberly, J., Cook, N., Calloway, A., Castro, F., & Charns, M. (2012). The sustainability of new programs and innovations: A review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 17–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-17

Tellegen, C. L., Ma, T., Day, J. J., Hodges, J., Panahi, B., Mazzucchelli, T. G., & Sanders, M. R. (2022). Measurement properties for a scale assessing self-regulation in parents and parenting practitioners. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(6), 1736–1748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02307-z

Turner, K., & Sanders, M. (1996). Parent consultation skills checklist. The University of Queensland.

Turner, K. M. T., Nicholson, J. M., & Sanders, M. R. (2011). The role of practitioner self-efficacy, training, program and workplace factors on the implementation of an evidence-based parenting intervention in primary care. Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-011-0240-1

Turner, K. M. T., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). Dissemination of evidence-based parenting and family support strategies: Learning from the Triple P-positive parenting program system approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(2), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.07.005

van de Mortel, T. F. (2008). Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-report research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(4), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.210155003844269

Weisenmuller, C., & Hilton, D. (2021). Barriers to access, implementation, and utilization of parenting interventions: Considerations for research and clinical applications. The American Psychologist, 76(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000613

Whittaker, K. A., & Cowley, S. (2012). An effective programme is not enough: A review of factors associated with poor attendance and engagement with parenting support programmes. Children and Society, 26(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2010.00333.x

Wolff, B., Knodel, J., & Sittitrai, W. (1993). Focus groups and surveys as complementary research methods: A case example. In Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art (pp. 118–136). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349008.n8

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research was supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (Project ID CE200100025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The Parenting and Family Support Centre is partly funded by royalties stemming from published resources of the Triple P–Positive Parenting Program, which is developed and owned by The University of Queensland (UQ). Royalties are also distributed to the Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences at UQ and contributory authors of published Triple P resources. Triple P International (TPI) Pty Ltd is a private company licensed by Uniquest Pty Ltd on behalf of UQ, to publish and disseminate Triple P worldwide. The authors of this report have no share or ownership of TPI. TPI had no involvement in the study design, or analysis or interpretation of data. Dr. Tellegen, Professor Sanders, and Mr. Ma are employees at UQ. Mr. Ma and Mr. Moller are students at UQ.

Ethical Approval

This study used existing data from a project where data were collected in accordance with approval granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of The University of Queensland (Ethics Clearance Number: 2021/HE000865).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish

Patients gave informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moller, N., Tellegen, C.L., Ma, T. et al. Facilitators and Barriers of Implementation of Evidence-Based Parenting Support in Educational Settings. School Mental Health 16, 189–206 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09629-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09629-3