Abstract

Secondary school staff are often tasked with delivering mental health content to students, yet there has been little research on staff confidence to do so. Given the responsibility placed on staff to support student mental health, reliable and valid measures are needed to facilitate assessment of teacher confidence in the classroom and evaluation of the impact of interventions designed to enhance teacher confidence and ultimately support the delivery of mental health interventions in schools. This study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the Teacher Confidence Scale for Delivering Mental Health Content (TCS-MH) and the What Worries Me Scale (WWMS), both developed by Linden and Stuart (2019) and previously tested on a sample of elementary school teachers. Within this paper we examine the factor structure, reliability, and validity of these measures in a large sample (N = 644) of secondary school staff. Exploratory factor analysis suggested that each scale had a single factor structure with all original items retained. This was further supported with confirmatory factor analysis. Examination of the reliability of both scales found that they had good internal consistency. Finally, through correlation analyses, both measures demonstrated satisfactory convergent and discriminant validity from mental health knowledge, mental health stigma, general anxiety, and teacher efficacy. Both the TCS-MH and the WWMS show great promise as measures of secondary school staff confidence to deliver mental health content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health promotion in secondary schools aims to teach students how to achieve and maintain mental health and well-being, reinforces protective factors for student mental health, creates a supportive environment, and reduces stigma around mental ill-health (Barry, 2019). Whole-school approaches to mental health promotion are increasingly prioritised as a way of enacting real lasting change for young people (Clarke, 2019; Lewallen et al., 2015). Evidence suggests that most secondary school staff see promoting student mental health as a key part of their job (Beames et al., 2022; Mælan et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2017). This includes the early identification of students who may be struggling and using referral pathways to connect students with support services and, naturally in a school setting, educating students about mental health (Beames et al., 2022; Kidger et al., 2010; Mazzer & Rickwood, 2015; Shelemy et al., 2019).

Mental health education involves increasing students’ mental health literacy; that is, increasing mental health knowledge, reducing stigma and improving help-seeking behaviours (Kutcher et al., 2016). Research on adolescents has shown that having low mental health literacy is a significant barrier to help-seeking (Aguirre Velasco et al., 2020) thus the need to prioritise education as part of school mental health promotion. Many mental health literacy interventions involve or rely on staff to deliver content to students; Patafio et al. (2021) found that 15% of these interventions in secondary schools were delivered by classroom teachers. Looking more broadly across mental health interventions, Franklin et al. (2012) found that staff were involved in over 40% of interventions and were the sole instructor in approximately 18%.

School staff confidence promoting mental health

While secondary school staff see promoting student mental health as a responsibility, studies suggest that they do not regard themselves as knowledgeable about mental health, and do not feel supported, capable, or competent to fulfil this aspect of their role (Askell-williams & Cefai, 2014; Berger et al., 2014; O’Reilly et al., 2018). In particular, staff have voiced concerns about taking on a therapeutic role with their students (Kidger et al., 2010; Mazzer & Rickwood, 2015; Shelemy et al., 2019) and saying the wrong thing to students with mental health issues and potentially making things worse (Ekornes, 2017; Mazzer & Rickwood, 2015; Shelemy et al., 2019). Many studies have highlighted that staff require extra training around knowledge of mental health disorders and how to offer support to students (Ekornes, 2017; Mazzer & Rickwood, 2015; Moon et al., 2017; O’Reilly et al., 2018), as well as how to educate students about mental health and adapt mental health resources to the needs of their classes (Shelemy et al., 2019).

Although secondary school staff confidence to promote mental health is a key issue, it is often overlooked in intervention studies. Recent systematic reviews by Anderson et al. (2019) and Yamaguchi et al. (2019) reported that mental health training interventions for school staff primarily focus on mental health knowledge and attitudes towards mental health. Only 38% of studies identified by Anderson et al. (2019), and 31% identified by Yamaguchi et al. (2019) examined staff confidence as an outcome, which typically referred to confidence helping students or others with mental health issues and not towards delivering mental health content.

While there is a lack of evidence around staff confidence to deliver mental health content, there has been a wealth of research carried out on teachers’ general confidence in relation to topics on the academic curriculum. Referred to variously in the literature as efficacy, confidence, or competence (Lauermann & Hagen, 2021), teacher efficacy is the perceived confidence teachers have to influence educational outcomes in their students (Klassen et al., 2011). Teacher efficacy impacts teachers’ decision making, the quality of their teaching, as well as their well-being (Lauermann & Hagen, 2021). Teachers with a higher sense of efficacy are more motivated, have a greater sense of personal accomplishment and are more committed to their work (Zee & Koomen, 2016). In terms of the effects on students, research indicates that if teachers have a greater sense of efficacy, students may be more engaged, more motivated, have a more positive outlook on their learning, and a better relationship with those teachers (Zee & Koomen, 2016).

Teacher confidence to deliver mental health content is a domain specific form of teacher efficacy, one that has been overlooked in the literature. This is in spite of the fact that staff are frequently tasked with delivering mental health content to students. To ensure that students are engaged and motivated to learn about mental health and that staff are committed and delivering high quality lessons about mental health, examination of staff confidence in this area should be a priority.

Measuring Staff Confidence

One reason for a lack of evidence on staff confidence to deliver mental health content could be a paucity of valid and reliable measures for use in mental health training interventions. Linden and Stuart (2019) developed the Teacher Confidence Scale for Delivering Mental Health Content (TCS-MH) to assess how confident staff feel about delivering mental health content in the classroom. It was based on a more general measure of teacher efficacy (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001) and was refined through consultation with education experts.

The authors of the TCS-MH suggested that lack of confidence in staff is often due to worries around the potentially negative outcomes of discussing mental health with students. Thus they developed the What Worries Me Scale (WWMS; Linden & Stuart, 2019). In testing the measures, the authors found a moderate negative correlation between the TCS-MH and the WWMS suggesting that confidence and worries were related but separate constructs. Linden and Stuart (2019) proposed that administering both the TCS-MH and the WWMS together offers a rounded view of staff confidence to deliver mental health content.

These measures were originally tested on a sample of elementary school teachers in Canada and showed potential as measures of confidence and staff worries. The measures are designed to be applicable to different contexts and do not reflect the content of any one specific mental health intervention. Validated measures are invaluable for future researchers seeking to understand or improve staff confidence to deliver mental health content as part of school-based mental health promotion. However, further assessment of the measures’ reliability, and validity is warranted. In addition, the measures have not yet been tested outside the Canadian cultural context or in other school contexts such as with secondary school staff.

The Present Study

The present study aimed to assess the psychometric properties of the TCS-MH and the WWMS for use in the secondary school context. Specifically, the objectives of this study were to examine the factor structure of both scales and to examine the reliability and construct validity of the measures when used in a sample of secondary school staff in Ireland.

To examine the construct validity of the TCS-MH and the WWMS, specifically to examine the convergent and discriminant validity of both measures, additional measures related to mental health promotion and general teacher efficacy were also included in this study: Mental health knowledge was included as most mental health training interventions for staff focus on mental health knowledge and it is a central component of any whole school mental health promotion activity in schools (Public Health England & Department for Education, 2021). Researchers have also suggested that staff with higher mental health knowledge could be predicted to have greater confidence in promoting mental health (Askell-Williams & Cefai, 2014). It was expected that there would be a positive association between this and staff confidence and a negative association between it and staff worries.

Stigma is another frequent focus of mental health interventions for staff, and the reduction of stigma towards mental ill health and mental health treatment is key to mental health promotion in schools (Ma et al., 2023). Research has further suggested that school staff with lower levels of stigma are more likely to provide mental health information to students (Sánchez et al., 2021). In looking at the validity of both the TCS-MH and the WWMS, examining the association with stigma was crucial, thus a measure was included. It was expected that those with greater stigma would have lower confidence and more worries around delivering mental health content.

Teacher efficacy was also included in the study; as the TCS-MH measures a domain specific form of efficacy, and as the measure was based on a measure of teacher efficacy, it was expected that the two would be positively related. However, given the specificity of the TCS-MH, and that in the literature many school staff have reported that they feel untrained to address mental health issues, it was expected that the association between general efficacy and confidence to deliver mental health content would not be strong, thus reflecting the unique domain of efficacy measured by the TCS-MH.

A measure of anxiety was added to the survey to examine the validity of the WWMS as a measure of specific worries related to teaching mental health content rather than a measure of general anxiety. It was expected that there would be a positive association between the two indicating that those with higher anxiety in general would have more worries about delivering mental health content. However, similar to the association between the TCS-MH and efficacy, the association was not expected to be strong, suggesting that the WWMS is capturing something more nuanced than general worry or anxiety.

Examining the psychometric properties of the TCS-MH and WWMS adds to the limited evidence around these measures, particularly their use in the secondary school context. To ensure school mental health promotion interventions are effective, reliable and valid measures are required to evaluate them. Measures of staff confidence and worries to deliver mental health content are important as school staff are increasingly tasked with educating young people about mental health; content that is frequently outside the realm of expertise of school staff. This study sought to investigate these measures to determine if they could be recommended for use in the evaluation of mental health promotion interventions in secondary schools.

Method

Design and Recruitment

This study involved a cross-sectional online survey conducted between February and March 2021. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from University College Dublin Human Research Ethics Committee.

The study was advertised across social media sites, on a national volunteering website, and by Jigsaw, the National Centre for Youth Mental Health in Ireland as part of their online courses for school staff. Participants were also recruited through snowball sampling, via social media groups and school staff mailing lists. Inclusion criteria for the present study included being over the age of 18 and being a member of staff working with adolescents in second level education in Ireland.

The Irish Education System

Second level education in Ireland, or post-primary education, refers to the education of 12- to 18-year-olds after they have completed primary school. Second level education is broken into two cycles, junior and senior, both of which students usually complete in the same school (Department of Education, 2019). The minimum school leaving age in Ireland is 16. Those who leave mainstream secondary school may continue their education in Youthreach – an education and training programme for early school leavers (see Department of Further and Higher Education, Research Innovation, and Science, 2022).

Mental health promotion in schools in Ireland is complex and multi-faceted with school staff playing a vital role in coordinating and delivering content to students. This content forms part of the formal curriculum for junior cycle (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, 2021), through the delivery of programmes by external organisation, or through the provision of guidance education (Department of Education, 2022a). Mental health promotion and the delivery of mental health content is not the responsibility of any one staff member but is shared across the staff body; supporting youth mental health is regarded as everyone’s responsibility (Department of Education and Skills, 2013).

To reflect the diversity of roles in school mental health promotion and the wider emphasis on whole-school approaches to mental health promotion globally, this study was open to all second level school staff in Ireland.

Participants

The final sample included N = 644 secondary school staff. 80% of the sample identified as female (n = 514). The majority had over 15 years of experience in second level education (n = 295); n = 219 had between six and 15 years of experience, and n = 129 had less than five years of experience. 6% of the sample worked in Youthreach (n = 40). 55% of the sample reported that they had not previously received mental health training (n = 353). The majority of the sample were subject teachers (n = 444), although n = 79 of these also reported having an additional role in their school, for example as a year head or guidance counsellor. Details of the other roles in the sample and full demographics are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Participants were also asked about their school context. Table 1 details the types of schools represented by this sample and how this compares to national figures for secondary schools in Ireland for the same year. Overall, figures suggest that the sample is representative of the national picture.

Survey

The survey was developed in Qualtrics, and the measures were set to appear in a random order to overcome bias related to the order of the questions. Measure ranges, mean scores, and standard deviations for all variables are provided in Table 2.

TCS-MH (Linden & Stuart, 2019)

The 12 items in this measure of participants’ confidence to deliver mental health content were scored on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not confident at all to 10 = very confident. Higher total scores indicate greater confidence. Participants were asked to rate their confidence on a series of statements such as, “I can answer students’ general questions about mental health.” In examining the psychometric properties of the measure, the original authors proposed a single factor structure for the TCS-MH, and found that the measure had good internal consistency (α = 0.96; Linden & Stuart, 2019).

WWMS (Linden & Stuart, 2019)

The 11 items in this measure of participants’ concerns about teaching mental health were scored on a 10-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 10 = strongly agree. Higher sores indicate higher levels of worry about teaching mental health content. Participants were asked to rate to what extent they agree with a series of potential worries, such as “I worry I may trigger an emotional reaction in a student with a mental health difficulty”. The original authors proposed a single factor structure for the WWMS, although they also acknowledged that there was potential for retaining two factors. The authors also found that the measure had good internal consistency (α = 0.93; Linden & Stuart, 2019).

The Mental Health Knowledge Scale (MHKS; Dooley et al., 2014)

This seven-item measure asks participants to rate their agreement with statements about mental health. For example, “Mental health is a state of emotional well-being”. The measure is scored on a five-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Higher sores indicate greater mental health knowledge. This measure has previously demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.83; Dooley et al., 2014) and this was also found in the current study (ω = 0.87).

Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS; Evans-Lacko et al., 2011)

This measure of stigma examines prevalence and intended behaviour in different contexts: (1) living with, (2) working with, (3) living nearby and (4) continuing a relationship with someone with a mental health issue. In the present study, the items assessing prevalence of behaviour were not included in the survey as they are not included in the final score and are meant only to give context to the latter half of the measure. For the four items assessing intended behaviour, participants were asked to rate to what extent they agree with statements about their future behaviour, such as “In the future, I would be willing to live with someone with a mental health problem”. Each item was scored on a five-point Likert scale from 1 = agree strongly to 5 = disagree strongly. Higher sores indicate higher levels of stigma. A sixth “don’t know” response option is also included. The RIBS has previously demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.85; Evans-Lacko et al., 2011).

In the present study, two further items about stigma in the school setting were added to this measure: (1) “In the future, I would be willing to teach a student with a mental health problem” and (2) “in the future, I would be willing to provide support to a student with a mental health problem.” The original response options were retained for these items, but an additional “does not apply to me” option was added for non-teaching staff. This six-item measure demonstrated good internal consistency (ω = 0.82). The total mean scores for both the four-item and six-item RIBS are provided in Table 2. However, for analyses, only the six-item RIBS was used.

Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale - Short Form (TSES; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001) This 12-item measure of teacher efficacy presents participants with statements about various aspects of teaching and asks them to rate to what extent they feel they can accomplish each action. For example, “How much can you do to control disruptive behaviour in the classroom?” Each item is scored on a nine-point Likert scale from 1 = nothing/not at all to 9 = a great deal. Higher sores indicate a greater sense of efficacy. In the present study, an additional “does not apply to me” response option was added for non-teaching staff, e.g. school leadership or guidance staff who may not teach mainstream classes as part of their role. The TSES can be divided into three subscales: classroom management, student engagement, and instructional strategies. The short form of the TSES has previously demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.90; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001), this was echoed in the present study (ω = 0.89).

Anxiety (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)

The anxiety scale in the DASS-21 consists of seven items each presenting a symptom potentially indicative of anxiety. For example, “Over the past week, I was aware of dryness of my mouth”. Participants were asked to rate how often they experienced each symptom. The DASS-21 was scored on a four-point Likert scale from 0 = does not apply to me at all, to 3 = applied to me very much/ most of the time. Higher sores indicate higher levels of anxiety. The DASS-21 has previously demonstrated good internal consistency when used in a non-clinical sample (α = 0.82; Henry & Crawford, 2005), the present study also found that the measure had good reliability (ω = 0.85).

Missing Data

Examination of missing data found that the proportion of missing data was low for most measures, and that the data were missing at random (See Supplementary Table 2). Listwise deletion was employed as research suggests that in large representative samples where the proportion of missing data is small, this is an appropriate approach (Cheema, 2014; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Prior to analysis, listwise deletion was carried out for the TCH-MH and WWMS. Descriptive statistics were analysed before and after listwise deletion on all demographic data and measures; while the sample size was slightly reduced (n = 594 after listwise deletion), there were no significant differences between the data before and after deletion.

Data Analysis

As the scales had only been assessed once before and because the scales were now being tested in both a different cultural and educational context, it was decided that further exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were warranted (Bandalos & Finney, 2019; DeVellis, 2017). However, to further investigate the structure of both of these scales, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were also carried out on both measures. To avoid conducting EFA and CFA on the same data, the sample was randomly split into two subsamples (Knekta et al., 2019), a process followed in similar studies (e.g. Clark & Malecki, 2019; Nearchou et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2020), and made possible by the large sample size of the present study (n = 594). To ensure the samples were equivalent, means and standard deviations for all items on the TCS-MH and WWMS were examined. A comparison of demographics and total scores for both subsamples was also carried out. Independent samples t-tests and chi square analyses found no significant differences between the two subsamples.

EFAs were carried out on the TCS-MH and WWMS on the first subsample using principal axis factoring (PAF) with promax rotation in IBM SPSS version 26. Scree plots and parallel analyses (O’Connor, 2000) were used to determine how many factors to retain. CFAs using robust weighted least squares estimation (WLSMV) was carried out individually for both measures on the second subsample in MPlus 8. The model fit was determined using the following criteria and indices (Brown, 2015; Ullman, 2019): The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), where a value < 0.08 indicates good fit, and the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), where, for both, > 0.90 indicates a good fit.

The chi-square statistic and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were reported for both measures in line with standard practice, however they were not used to determine model fit. The chi-square is an overly strict estimate (Mueller & Hancock, 2019) that is sensitive to sample size, particularly with factors with a large number of indicators and response categories (Knekta et al., 2019; Moshagen & Musch, 2014), and often favours complex models (Alavi et al., 2020). Research suggests that RMSEA is also sensitive to sample size, particularly if there are a higher number of variables, and is regarded as less accurate than SRMR (Maydeu-Olivares, 2017; Maydeu-Olivares et al., 2018), particularly in models with ordinal data (Shi et al., 2020). Research further suggests that RMSEA may also reject correctly specified models in cases where the measures used are of high quality with good reliability, and have high factor loadings (McNeish et al., 2018; Prudon, 2015).

The reliability of the TCS-MH and WWMS was examined using McDonald’s omega as this is considered a more accurate estimate of reliability than Cronbach’s alpha (Trizano-Hermosilla & Alvarado, 2016), that is also not as constrained by the assumption of tau-equivalence (McNeish, 2018). Convergent and discriminant validity; how both the TCS-MH and WWMS behave with regard to other measures (DeVellis, 2017), was investigated through bivariate correlation analyses. Firstly, the association between the TCS-MH and the WWMS was examined; the original authors suggested a moderate negative association between the two measures (Linden & Stuart, 2019). Secondly, bivariate correlation analyses were carried out to examine the association between staff confidence to deliver mental health content and mental health knowledge, stigma, and teacher efficacy. Staff worries was examined in relation to mental health knowledge, stigma, and anxiety.

Additional analyses were carried out to examine group differences on staff confidence and staff worries. Independent sample t-tests were used to examine differences in confidence and worries based on gender, role in the school, various school demographics, or whether participants had completed previous mental health training. One-way analysis of variance tests were carried out to examine whether confidence and worries differed significantly depending on school size or participants’ level of teaching experience.

Results

Exploratory Factor Analyses

Using one of the sub-samples (n = 289) EFA was carried out on the 12 items of the TCS-MH. PAF was employed as the extraction method and promax rotation was initially applied to the analysis. The items of the TCS-MH were determined to be suitable for factor analysis; the correlation matrix confirmed the presence of many coefficients of 0.3 and above, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.95, exceeding the recommended value of 0.6, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < .001; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Examination of the scree plot and parallel analysis suggested a single factor structure. As a result of this finding, the factor analysis was re-run forcing a single factor structure. All 12 items loaded strongly onto this single factor (see Table 3).

The same procedure was followed in the examination of the 11 items of the WWMS. The items of the WWMS were determined to be suitable for factor analysis; the correlation matrix confirmed the presence of many coefficients of 0.3 and above, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.92, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity reached statistical significance (p < .001). Similar to the TCH-MH, examination of the scree plot and subsequent parallel analysis suggested a single factor structure. As such, the factor analysis was re-run forcing a single factor structure. All 11 items loaded strongly onto this single factor (see Table 3).

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

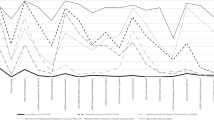

The 12-item, single factor model of the TCS-MH was further analysed through CFA with WLSMV estimation using the second subsample (n = 305). Overall, analysis indicated an adequate model fit: x2 (54, N = 305) = 620.24, p < .001, SRMR = 0.03, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.19 [0.17, 0.20]. The single factor structure was retained with all 12 items as the indices of interest suggested a good fit and all items loaded strongly onto the model (see Fig. 1 for final model and factor loadings).

The 11-item, single factor model of the WWMS was also analysed through CFA with WLSMV estimation using the second subsample (n = 305). The model was found to have adequate fit: x2 (44, N = 305) = 520.42, p < .001, SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.19 [0.17, 0.2]. The single factor structure was retained with all 11 items as the indices of interest suggested a good fit and all 11 items loaded strongly onto the model (see Fig. 1 for final model and factor loadings).

Reliability

The internal consistency of both measures was assessed using McDonald’s omega. Both measures demonstrated good reliability (TCS-MH ω = 0.96; WWMS ω = 0.92).

Construct Validity

To assess the construct validity of the TCHS-MH and the WWMS, a one-tailed Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the associations between scores on the two measures. A moderate, negative correlation was found between staff confidence to deliver mental health content and staff worries (r (592) = − 0.30, p < .001). Further one-tailed Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess the associations between the TCS-MH, WWMS, and other outcome variables. A weak, positive association was found between confidence to deliver mental health content and mental health knowledge (r (580) = 0.18, p < .001); a moderate, negative association was found between confidence to deliver mental health content and stigma (r (568) = − 0.31, p < .001); and a moderate, positive association was found between confidence to deliver mental health content and teacher efficacy (r (514) = 0.39, p < .001). There was no significant association between worries and mental health knowledge; a weak, negative association was found between worries and stigma (r (569) = 0.14, p < .001); and a weak, positive association was found between the worries and anxiety (r (581) = 0.26, p < .001). A correlation table for all variables is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Additional Analyses

To examine group differences on the TCS-MH and WWMS, demographic and school variables were examined using independent samples t-tests and one-way ANOVA tests Details of all tests are included in Supplementary Tables 4–12. Independent samples t-tests found a significant difference on the TCS-MH between males and females. Females reported significantly higher confidence (M = 88.87, SD = 20.28) than males (M = 82.74, SD = 21.54), (t (587) = -2.42, p = .015), with a small effect size; d = 0.25. There was no significant difference on the WWMS between males and females. Looking at school demographics, there was no significant difference on either variable between participants working in an urban or rural school, working in a single sex or mixed school, in a DEIS or non-DEIS school, or in a fee-paying or non-fee-paying school.

In terms of training and role in the school, there were significant differences on both variables. Those who reported having completed mental health training demonstrated significantly higher confidence (M = 96.97, SD = 15.68) than those with no training (M = 80.11, SD = 21.17), (t (582.35) = 11.11, p < .001) with a large effect size d = 0.89. Similarly, those with mental health training scored significantly lower on the WWMS (M = 43.57, SD = 20.08) than those without mental health training (M = 54.43, SD = 21.46), (t (590) = -6.32, p < .001) with a medium effect size; d = 0.52. Staff in a support position such as guidance counsellors, special education staff, year heads, and so on had significantly higher confidence (M = 91.87, SD = 20.93) than those not in a support role (M = 85.09, SD = 20.49), (t (557) = 3.61, p < .001) with a small effect size; d = 0.33. Staff in a support role also demonstrated significantly lower scores on the WWMS (M = 46.76, SD = 21.81) than those not in a support role (M = 51.09, SD = 20.98), (t (557) = -2.24, p = .025) with a small effect size; d = 0.20.

One-way ANOVA tests found no significant difference between early career staff (< 5 years of experience), experienced staff (5–15 years of experience), or very experienced staff (15 + years of experience) on the TCS-MH or WWMS. Similarly, there was no significant difference in terms of confidence or worries between participants working in a small school (< 500 students), a medium sized school (500–700 students), or a large school (700 + students).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the psychometric properties of the TCS-MH and the WWMS (Linden & Stuart, 2019) when used with a sample of secondary school staff in Ireland. The findings of this study suggest that both measures have good reliability and validity beyond the cultural and education context in which they were originally tested.

Both the EFA and CFA supported the single-factor structure for each measure suggested by Linden and Stuart (2019), with no change to either measure. It is generally recommended that no one criterion should be relied upon to assess model fit in a CFA (Brown, 2015; Kline, 2016; Ullman, 2019), thus several indices for model fit were used in the present study. The CFI, TLI, and SRMR criteria were met for both measures, all items loaded strongly, and both measures demonstrated good reliability.

Analyses of correlations in the present study allowed for the examination of the measures’ validity. Most outcome variables performed as expected when measured against the TCS-MH and WWMS, thus supporting the construct validity of the measures. However, none of the associations were strong and mental health knowledge was not associated with scores on the WWMS; further discussion is thus warranted. Expertise in a subject is an essential part of pedagogical content knowledge, that is, a teacher’s ability to combine subject knowledge with effective teaching strategies (Loughran et al., 2012). As such, it would be reasonable to expect a stronger association between participants’ level of mental health knowledge and their confidence to deliver this type of content. Furthermore, mental health knowledge was not significantly associated with staff worries about delivering mental health content as expected. It is worth noting that overall, participants demonstrated good mental health knowledge (M = 27.95, SD = 4.44), with average scores well above the mid-point of the scale (17.5) and that the measure in question focuses primarily on knowledge of positive mental health. While future research may benefit from examining the TCS-MH and the WWMS against a different measure of mental health knowledge, reviews have demonstrated that there are issues with most existing measures, including scales and vignettes (Fulcher & Pote, 2021; O’Connor et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2015).

Stigma was not strongly associated with either confidence or worries. A comparison of the RIBS scores on the original four-item measure and the extended six-item measure revealed that the mean score for stigma was slightly higher in the latter (RIBS 4 item M = 6.16, SD = 2.56; RIBS 6 item M = 8.65, SD = 3.23). As these items specifically examined stigma in the school context, future research into stigma in the school context would shed further light on staff confidence and worries. Furthermore, the RIBS measures stigma by assessing behavioural intentions with regard others with mental health issues in general, an examination of other aspects of stigma, such as stereotypes or prejudice (Corrigan & Shapiro, 2010), could expand understanding of staff confidence and worries to deliver mental health content, particularly as school staff cannot choose which students they encounter in the course of their work.

General teacher efficacy was moderately associated with scores on the TCS-MH. As previously mentioned, the TCS-MH purports to measure a domain specific form of teacher efficacy and was originally based on the TSES. The moderate association in this case is to be welcomed as it suggests that despite the close theoretical relationship between the two constructs, the TCS-MH has good discriminant validity from general teaching efficacy (DeVellis, 2017). Similarly, it was expected that anxiety would be associated with staff worries as they are similar constructs, and indeed, anxiety was weakly associated with staff worries. This confirms that the WWMS has discriminant validity and is not simply a measure of general worries or anxiety.

Additional analyses looking at group differences found significant differences based on previous mental health training and whether staff held a student support role. These findings lend credence to the validity of these measures as only variables related to supporting student mental health were related to staff confidence and staff worries around delivering mental health content in schools.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. The study design allowed for data collection across a variety of variables related to school-based mental health promotion. This broad range of outcomes allowed for the investigation of convergent and discriminant validity beyond the evidence put forward previously around these measures. Furthermore, the evidence around validity and reliability was garnered from a wide sample of secondary school staff beyond just teaching staff. As previously mentioned, whole-school approaches to mental health promotion are becoming increasingly popular. In such approaches, mental health promotion is not the sole responsibility of teachers, it is something that all school staff are involved in. This approach to mental health promotion is central to how students in Ireland are taught about mental health. As such, this study was open to all secondary school staff. To check the robustness of the results using this sampling approach, all analysis was also carried using just the data from teaching staff. Results for the EFAs, CFAs, and correlations followed the same pattern as the results presented in this paper. A further strength of this study was the sample size. This study recruited N = 644 participants making it possible to split the sample and conduct both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, further expanding our understanding of these measures.

The present study is not without its limitations. In terms of the sample, there was an over representation of females (80%). While national figures do suggest that there are a greater number of female school staff in Ireland (68% female in 2020/2021; Department of Education, 2021b), the gender ratios in the current sample suggests that the sample may not be entirely representative of the population. Further comparison between the demographics in the present study and national figures is not possible due to the lack of national data on school staff in Ireland. In addition, as this study was advertised widely on social media, the sample may also be further biased as the many participants may have elected to take part due to an existing interest in mental health promotion in their work.

Further limitations include the following: While this study captured information regarding participants’ demographics and mental health training, it did not capture whether participants had experience delivering mental health content to students, the addition of this variable would have provided further insight into the participant group and may have affected their scores on the TCS-MH and WWMS. In terms of the factor analysis, not all common fit indices for the CFA were met. While, as mentioned above, there is evidence to suggest that despite this, the models fit well, it is worth noting that the measures could be improved with further analysis in the future. Finally, assessments of measurement invariance for the TCS-MH and WWMS were outside of the scope of this study. Future research establishing measurement invariance for both measures across groups and over time would offer invaluable insight into the utility of these measures (Schmitt & Kuljanin, 2008; Van De Schoot et al., 2015).

Conclusion

Secondary school staff often deliver content to students as part of mental health promotion interventions. However, little is known about staff confidence to fulfil this aspect of their role. Having reliable and valid measures of staff confidence is imperative for the evaluation of school-based mental health promotion interventions. The present study has provided an assessment of the psychometric properties of the TCS-MH and WWMS when applied to a sample of secondary school staff. The present study provides evidence of the factor structure, reliability, and validity of both scales, building on the findings of Linden and Stuart (2019) and expanding the evidence for the use of these measures in other contexts. The findings of this study supported the single factor structure of both measures as proposed by the original authors as well as the retention of all original items. The current study found that these measures were both reliable and had good convergent and discriminant validity with other mental health promotion and teacher specific outcomes. Both of these measures would be of benefit for researchers looking to further understand or improve secondary school staff confidence to deliver mental health content.

Data Availability

The data, survey, information sheet, and debriefing information for this study has been archived with the Irish Social Science Data Archive (ISSDA) and is available for use by researchers: https://www.ucd.ie/issda/data/schoolstaffconfidence/.

References

Aguirre Velasco, A., Silva Santa Cruz, I., Billings, J., Jimenez, M., & Rowe, S. (2020). What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 20(293), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02659-0.

Alavi, M., Visentin, D. C., Thapa, D. K., Hunt, G. E., Watson, R., & Cleary, M. (2020). Chi-square for model fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(9), 2209–2211. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14399.

Anderson, M., Werner-Seidler, A., King, C., Gayed, A., Harvey, S. B., & O’Dea, B. (2019). Mental Health Training Programs for secondary School Teachers: A systematic review. School Mental Health, 11, 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9291-2.

Askell-williams, H., & Cefai, C. (2014). Australian and maltese teachers ’ perspectives about their capabilities for mental health promotion in school settings. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.003.

Bandalos, D. L., & Finney, S. J. (2019). Factor analysis: Exploratory and confirmatory. In G. R. Hancock, L. M. Stapleton, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 98–135). Routledge.

Barry, M. M. (2019). Concepts and Principles of Mental Health Promotion. In M. M. Barry, A. M. Clarke, I. Peterson, & R. Jenkins (Eds.), Implementing Mental Health Promotion (pp. 3–34). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23455-3.

Beames, J. R., Johnston, L., O’Dea, B., Torok, M., Boydell, K., Christensen, H., & Werner-Seidler, A. (2022). Addressing the mental health of school students: Perspectives of secondary school teachers and counselors. International Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 10(1), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2020.1838367.

Berger, E., Hasking, P., & Reupert, A. (2014). Erratum to: We’re working in the Dark Here: Education needs of Teachers and School Staff regarding Student Self-Injury. School Mental Health, 6, 295–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-014-9135-7.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for Applied Research. The Guilford Press.

Cheema, J. R. (2014). Some general guidelines for choosing missing data handling methods in educational research. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 13(2), 53–75. https://doi.org/10.22237/jmasm/1414814520.

Clark, K. N., & Malecki, C. K. (2019). Academic grit scale: Psychometric properties and associations with achievement and life satisfaction. Journal of School Psychology, 72, 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.12.001.

Clarke, A. M. (2019). Promoting Children’s and Young People’s Mental Health in Schools. In M. M. Barry, A. M. Clarke, I. Peterson, & R. Jenkins (Eds.), Implementing Mental Health Promotion (pp. 303–340). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23455-3.

Corrigan, P. W., & Shapiro, J. R. (2010). Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.004.

Department of Education (2022a). Working as a post-primary guidance counsellor in Ireland 2022. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/63c5f-guidance-counselling-in-schools/.

Department of Education (2019). Education. https://www.gov.ie/en/policy/655184-education/.

Department of Education (2022b). DEIS Delivering Equality of Opportunity In Schools. https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/4018ea-deis-delivering-equality-of-opportunity-in-schools/.

Department of Education (2021b). Teacher Statistics. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/c97fbd-teacher-statistics/.

Department of Education and Skills (2013). Well-Being in Post-Primary Schools: Guidelines for mental health promotion and suicide prevention. https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/304928.

Department of Further and Higher Education, Research Innovation, and Science (2022). Youthreach. https://www.gov.ie/en/service/5666e9-youthreach/.

Department of Education (2021a). Data on Individual Schools. https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/63363b-data-on-individual-schools/.

DeVellis, R. F. (2017). Scale development: Theory and applications. SAGE Publications Inc.

Dooley, B., Fitzgerald, A., & Donnelly, A. (2014). Mental health awareness initiative (MHAI): Evaluation report. University College Dublin.

Ekornes, S. (2017). Teacher stress related to Student Mental Health Promotion: The Match between Perceived demands and competence to help students with Mental Health problems. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(3), 333–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1147068.

Evans-Lacko, S., Rose, D., Little, K., Flach, C., Rhydderch, D., Henderson, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2011). Development and psychometric properties of the reported and intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS): A stigma-related behaviour measure. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 20(3), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796011000308.

Franklin, C. G. S., Kim, J. S., Ryan, T. N., Kelly, M. S., & Montgomery, K. L. (2012). Teacher involvement in school mental health interventions: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(5), 973–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.027.

Fulcher, E., & Pote, H. (2021). Psychometric properties of global mental health literacy measures. Mental Health Review Journal, 26(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-04-2020-0022.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239.

Kidger, J., Gunnell, D., Biddle, L., Campbell, R., & Donovan, J. (2010). Part and parcel of teaching? Secondary school staff’s views on supporting student emotional health and well-being. British Educational Research Journal, 36(6), 919–935. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903249308.

Klassen, R. M., Tze, V. M. C., Betts, S. M., & Gordon, K. A. (2011). Teacher efficacy research 1998–2009: Signs of progress or unfulfilled promise? Educational Psychology Review, 23, 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9141-8.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. The Guildford Press.

Knekta, E., Runyon, C., & Eddy, S. (2019). One size doesn’t fit all: Using factor analysis to gather validity evidence when using surveys in your research. CBE Life Sciences Education, 18(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-04-0064.

Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., & Coniglio, C. (2016). Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(3), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743715616609.

Lauermann, F., & Hagen, I. (2021). Do teachers ’ perceived teaching competence and self-efficacy affect students ’ academic outcomes? A closer look at student-reported classroom processes and outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 56(4), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2021.1991355.

Lewallen, T. C., Hunt, H., Potts-Datema, W., Zaza, S., & Giles, W. (2015). The Whole School, Whole Community, whole child model: A New Approach for improving Educational Attainment and Healthy Development for students. Journal of School Health, 85(11), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12310.

Linden, B., & Stuart, H. (2019). Preliminary analysis of validation evidence for two new scales assessing teachers’ confidence and worries related to delivering mental health content in the classroom. BMC Psychology, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0307-y.

Loughran, J., Berry, A., & Mulhall, P. (2012). Pedagogical content knowledge. In J. Loughran, A. Berry, & P. Mulhall (Eds.), Understanding and developing Science Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge (pp. 7–14). Sense Publishers.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation.

Ma, K. K. Y., Anderson, J. K., & Burn, A. (2023). School-based interventions to improve mental health literacy and reduce mental health stigma – A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 28(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12543.

Mælan, E. N., Tjomsland, H. E., Baklien, B., Samdal, O., & Thurston, M. (2018). Supporting pupils’ mental health through everyday practices: A qualitative study of teachers and head teachers. Pastoral Care in Education, 36(1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2017.1422005.

Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2017). Assessing the size of Model Misfit in Structural equation models. Psychometrika, 82(3), 533–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-016-9552-7.

Maydeu-Olivares, A., Shi, D., & Rosseel, Y. (2018). Assessing fit in Structural equation models: A Monte-Carlo evaluation of RMSEA Versus SRMR confidence intervals and tests of close fit. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 25(3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1389611.

Mazzer, K. R., & Rickwood, D. J. (2015). Teachers’ role breadth and perceived efficacy in supporting student mental health. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 8(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2014.978119.

McNeish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144.

McNeish, D., An, J., & Hancock, G. R. (2018). The Thorny Relation between Measurement Quality and Fit Index Cutoffs in Latent Variable Models. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2017.1281286.

Moon, J., Williford, A., & Mendenhall, A. (2017). Educators’ perceptions of youth mental health: Implications for training and the promotion of mental health services in schools. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.006.

Moshagen, M., & Musch, J. (2014). Sample size requirements of the robust weighted least squares estimator. Methodology, 10(2), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000068.

Mueller, R. O., & Hancock, G. R. (2019). Structural equation modeling. In R. Hancock, M. Gregory, L. Stapleton, O. Mueller, & Ralph (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 446–456). Routledge.

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (2021). Junior cycle wellbeing guidelines. https://ncca.ie/en/resources/wellbeing-guidelines-for-junior-cycle/.

Nearchou, F., O’Driscoll, C., McKeague, L., Heary, C., & Hennessy, E. (2021). Psychometric properties of the peer Mental Health stigmatization scale-revised in adolescents and young adults. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 15(1), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12933.

O’Connor, B. P. (2000). SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behavior Research Methods Instrumentation and Computers, 32, 396–402. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03200807.

O’Connor, M., Casey, L., & Clough, B. (2014). Measuring mental health literacy—A review of scale-based measures. Journal of Mental Health, 23(4), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2014.910646.

O’Reilly, M., Adams, S., Whiteman, N., Hughes, J., Reilly, P., & Dogra, N. (2018). Whose responsibility is adolescent’s Mental Health in the UK? Perspectives of key stakeholders. School Mental Health, 10(4), 450–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9263-6.

Patafio, B., Miller, P., Baldwin, R., Taylor, N., & Hyder, S. (2021). A systematic mapping review of interventions to improve adolescent mental health literacy, attitudes and behaviours. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13109.

Prudon, P. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis as a tool in research using questionnaires: A critique. Comprehensive Psychology, 4, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2466/03.CP.4.10.

Public Health England & Department for Education (2021). Promoting children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. A whole school or college approach. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/promoting-children-and-young-peoples-emotional-health-and-wellbeing.

Sánchez, A. M., Latimer, J. D., Scarimbolo, K., Von Der Embse, N. P., Suldo, S. M., & Salvatore, C. R. (2021). Youth Mental Health First Aid (Y-MHFA) trainings for educators: A systematic review. School Mental Health, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09393-8.

Schmitt, N., & Kuljanin, G. (2008). Measurement invariance: Review of practice and implications. Human Resource Management Review, 18(4), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.03.003.

Shelemy, L., Harvey, K., & Waite, P. (2019). Supporting students’ mental health in schools: What do teachers want and need? Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 24(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2019.1582742.

Shi, D., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Rosseel, Y. (2020). Assessing fit in Ordinal factor analysis models: SRMR vs. RMSEA. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 27(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1611434.

Sun, M., Du, J., & Xu, J. (2020). The validation of the Teachers’ goal orientations for Professional Learning Scale (TGOPLS) on information technology. Technology Pedagogy and Education, 29(5), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1808523.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson Education Limited.

Trizano-Hermosilla, I., & Alvarado, J. M. (2016). Best alternatives to Cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00769.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1.

Ullman, J. B. (2019). Structural equation modeling. In B. G. Tabachnick, & L. S. Fidell (Eds.), Using multivariate statistics (pp. 528–612). Pearson Education Limited.

Van De Schoot, R., Schmidt, P., De Beuckelaer, A., Lek, K., & Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, M. (2015). Editorial: Measurement Invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01064.

Wei, Y., McGrath, P. J., Hayden, J., & Kutcher, S. (2015). Mental health literacy measures evaluating knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking: A scoping review. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0681-9.

Yamaguchi, S., Foo, J. C., Nishida, A., Ogawa, S., Togo, F., & Sasaki, T. (2019). Mental health literacy programs for school teachers: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12793.

Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its Effects on Classroom processes, Student Academic Adjustment, and Teacher Well-Being: A synthesis of 40 years of Research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626801.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr Neil Mac Dhonnagáin for his assistance with the statistical analyses in this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Irish Research Council (Project ID: EBPPG/2020/106).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Maeve Dwan-O’Reilly and Laura Walsh. Data analysis was performed by Maeve Dwan-O’Reilly. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Maeve Dwan-O’Reilly and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of University College Dublin (reference number: HS-E-20-154-OReilly-Hennessy).

Consent

Informed Consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The participants also consented to the publication of the study data.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dwan-O’Reilly, M., Walsh, L., Booth, A. et al. Measuring School Staff Confidence and Worries to Deliver Mental Health Content: An Examination of the Psychometric Properties of Two Measures in a Sample of Secondary School Staff. School Mental Health 16, 41–52 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09616-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09616-8