Abstract

Tackling mental health difficulties in adolescents on the autism spectrum requires a comprehensive prevention approach. A 3-year multisite proof-of-concept longitudinal study implemented an evidence-based multilevel resilience intervention in schools to promote protective factors at the adolescent, parent, and school level. The intervention, consisting of the adolescent, parent and teacher components of the Resourceful Adolescent Program–Autism Spectrum Disorder (RAP-ASD) augmented with the Index for Inclusion, was implemented in 6 secondary schools with 30 adolescents with an autism diagnosis in Grades 7 and 8, 31 parents of 23 of the adolescents, and school staff. The intervention was implemented with good validity and acceptability. Quantitative data from adolescents and parents were analysed using the Reliable Change Index, and qualitative data were analysed using Consensual Qualitative Research. Triangulated quantitative and qualitative outcomes from the majority of adolescents and their parents showed some evidence for promoting resilience for adolescents with a diagnosis or traits of autism, as reflected in reliable improvements in coping self-efficacy and school connectedness, and a reduction in anxiety symptoms and emotional and behavioural difficulties. A reliable improvement in depressive symptoms was more modest and was only achieved by a small minority of adolescents. This multilevel, strength-focused, resilience-building approach represents a promising and sustainable school-based primary prevention program to improve the quality of life for adolescents on the spectrum by promoting their mental health and providing their families with much needed support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The risk of developing depression increases in early adolescence, with young adolescents on the autism spectrum at greater risk than their neurotypical peers (Hossain et al., 2020; Hudson et al., 2019; Mayes et al., 2011). While depression and other mental health difficulties (e.g. anxiety) in adolescents on the autism spectrum can impact severely on both current and future developmental prospects, there is a paucity of research on early intervention and prevention approaches to prevent or ameliorate these difficulties for adolescents on the spectrum. Emerging depression prevention research suggests that intervening at the multiple levels of adolescent, parent, and school may be a promising way forward (Francis, 2005; Mackay et al., 2017). This study reports on the quantitative and qualitative outcomes of a 3-year multisite proof-of-concept longitudinal studyFootnote 1 that implemented an evidence-based, strength-focused, multilevel resilience intervention with young adolescents on the autism spectrum, their parents, and their schools to prevent depression and other mental health problems for the adolescents. The proof-of-concept phase is an important step in intervention research because it provides a cost-effective method of determining whether an intervention can realise a clinically significant improvement in a small, select sample.

Mental Health Problems Experienced by Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health disorders experienced by adolescents (Farrell & Barrett, 2007). While anxiety disorders tend to emerge around 6 years of age, and more than 50% of adolescents on the autism spectrum struggle with comorbid anxiety or depression, the incidence of depression increases significantly after early adolescence (Howlin, 2005; Merikangas et al., 2010). Compared to typically developing children, those on the autism spectrum experience the transition to adolescence as more challenging, their risk of developing depression is estimated as four times higher with prevalence estimated as high as 54%, and their risk of suicidal behaviour is increased (Hossain et al., 2020; Hudson et al., 2019; Mayes et al., 2011). Adolescents on the spectrum are more likely to feel lonely due to disengaging from peers and adults as a result of inherent communication and social interaction difficulties that intensify with the increasing social demands of early adolescence (Humphrey & Symes, 2010; White & Roberson-Nay, 2009). In addition, they tend to struggle with affect regulation due to difficulties with Theory of Mind, executive functions, and cognitive linguistic processes that interfere with recruitment of coping strategies to manage negative mood (Jahromi et al., 2013). Untreated depressive symptoms in young adolescents on the autism spectrum, whether clinical or subclinical, often extend into adulthood (Copeland et al., 2009) and, coupled with the young adult’s autism difficulties, interfere with engaging in and completing tertiary education (see Mojtabai et al., 2015 for review), and securing employment and remaining employed (Taylor et al., 2015).

Need for Early Intervention and Prevention for Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum

As prevention programs intervene in the developmental period immediately preceding the age of peak incidence to maximise treatment efficacy, many anxiety prevention programs target children, while depression prevention programs target early adolescence (see Gladstone et al., 2011 for review). A number of studies using cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) to treat anxiety in children on the autism spectrum have realised significant reductions in reported levels of anxiety (e.g. see Kreslins et al., 2015 for review of 10 randomised control trials (RCTs), N = 470). Adolescent depression prevention programs can result in a modest improvement in depressive symptomology, are more effective when targeting adolescents at risk (Corrieri et al., 2014; Merry et al., 2011), and many programs have realised some success in preventing and treating depression in adolescents not on the autism spectrum (see Stice, Shaw, Bohon, Marti, & Rohde, 2009 for review). Concerning adolescents on the spectrum, a small CBT program realised significant changes in reported levels of depression in older adolescents on the autism spectrum (Mage = 15.75 years; Santomauro et al., 2015). However, despite the high rate of depressive symptoms in adolescents on the autism spectrum, and the link between depression as a mediator of autism traits and diminished psychosocial outcomes (Chiang & Gau, 2016), there are no evidenced-based interventions for prevention and early intervention of depression for young adolescents on the spectrum (Ghaziuddin et al., 2002; Stewart et al., 2006).

Factors that Protect Adolescents Against Depression

Protective factors reduce the effects of adversity so as to achieve a positive outcome (Luthar et al., 2000). Resilience, a dynamic process consisting of positive adaptation despite adversity (Luthar et al., 2000), is inhibited by risk factors, and is promoted by protective factors (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005), with increased capacity for resilience detected in outcomes such as increased coping self-efficacy (measured using the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES; Chesney et al., 2006), improved behavioural and emotional functioning (measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997), and reduced depressive symptoms (measured using the Children’s Depression Inventory 2 (CDI 2; Kovacs & MHS Staff, 2011). Two factors that protect against the development of depression by building resilience are the sense of belonging, and the capacity for self- and affect regulation.

School belonging, in the form of school connectedness, is the extent to which a student feels accepted, valued, and supported in their school environment (Goodenow, 1993; Shochet, 2016), and is routinely measured using the self-report Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (PSSM; Goodenow, 1993). Self-regulation is the ability to override unhelpful impulses and responses with a more helpful, adaptive response (Baumeister et al., 2007). Affect regulation is a process triggered by self-regulation that monitors and moderates internal feeling states (e.g. mood) to enhance or diminish mental health and wellbeing (Eisenberg et al., 2000; Fledderus et al., 2010). School connectedness is an important protective factor for current and future mental wellbeing in adolescents: a stronger sense of school connectedness has been associated with positive outcomes such as support from peers and teachers, greater academic engagement and achievement (Anderman, 2002; Monahan et al., 2010), while lower connectedness has been associated with increased depressive symptoms, lower self-esteem, diminished optimism, greater paranoid tendencies, social withdrawal, and loneliness (e.g. Chapman et al., 2013; Shochet & Smith, 2012; Shochet et al., 2006). Shochet et al. (2006) found that school connectedness and depressive symptoms were highly correlated, with school connectedness sharing up to 55% of the variance with adolescent depression. School connectedness also predicted future depressive symptoms even when controlling for prior symptoms of depression.

Research on self- and affect regulation has shown a significant relationship with depression and other mental health problems, and that the two protective factors of school connectedness and self- and affect regulation are interrelated: the greater the experience of school connectedness, the greater the capacity for self- and affect regulation, and vice versa. Self- and affect regulation increase young adolescents’ ability to manage difficult interpersonal situations, leading to more positive social interactions with peers (Buckley & Saarni, 2009; Finkel & Fitzsimons, 2011; Shochet & Ham, 2003; Vohs & Finkel, 2006), which in turn, generates a greater sense of connectedness (Zhao & Zhao, 2015). Further, a sense of belonging and feeling connected to others appears to facilitate self- and affect regulation (Beckes & Coan, 2011) and, as a result of their protective role, reduced depressive symptoms (Roberts & Burleson, 2013). Hence, promoting the interrelated protective factors of school connectedness and self- and affect regulation is important in the prevention of depression.

Preventing Depression in Young Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum

Young adolescents on the autism spectrum experience significant adversity that requires a resilience process (Shochet et al., 2016). Research exploring the use of strength-based programs to promote wellbeing and prevent depression in adolescents on the spectrum by building their resilience is in its infancy (for promising work in this area see Groden et al., 2011; Lam et al., 2020). School-based depression prevention programs represent a gold standard of intervention as they are affordable, accessible, sustainable, and have been supported empirically (Corrieri et al., 2014). An evidence-based, strength-focused resilience program implemented in schools to promote the protective factors of school connectedness and self- and affect regulation in young adolescents not on the autism spectrum to protect against the development of depression is the multilevel Resourceful Adolescent Program (RAP) (Shochet & Wurfl, 2015a, 2015b; Shochet et al., 1997a, 1997b). RAP has been implemented worldwide, and its efficacy has been established in a number of RCTs (see Merry et al., 2004; Shochet et al., 2001, 2016 for detail). RAP consists of three components: the Resourceful Adolescent Program for Adolescents (RAP-A; Shochet, Holland, & Whitfield, 1997a, 1997b), the Resourceful Adolescent Program for Parents (RAP-P), and the Resourceful Adolescent Program for Teachers (RAP-T).

Resourceful Adolescent Program for Adolescents

RAP-A is based on elements of cognitive-behavioural theory (stress management, cognitive restructuring, and problem solving strategies), and Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) (promoting connectedness, and developing skills that reduce interpersonal conflict), both of which have a solid evidence base for the treatment of depression, as well as anxiety, in young adolescents (Clarke et al., 2001; Garber, 2006; Garber, Clarke, et al., 2009; Horowitz, Garber, Ciesla, Young, & Mufson, 2007; Merry et al., 2004; Rivet-Duval, Heriot, & Hunt, 2011). RAP-A is designed to be delivered in a universal format with whole cohorts of neurotypical students aged 11 – 15 as an 11-session group program delivered weekly across one school term but can also be delivered in a selected or indicated format (Merry et al., 2004; Muris, Bogie, & Hoogsteder, 2001; Shochet et al., 2001).

RAP–A has been adapted and manualised for young adolescents on the spectrum with low support needs aged 11 to 15 (Resourceful Adolescent Program for Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum (RAP-A-ASD; Shochet & Wurfl, 2019a, 2019b). Adaptations were designed to mitigate the difficulties that young adolescents on the spectrum typically experience. These difficulties include diminished Theory of Mind (the capacity to understand that others’ thoughts and feelings differ from one’s own), which interferes with understanding an experience from another’s point of view (Attwood, 2007); identifying, understanding and expressing emotions which reduces the ability to describe one’s mood changes to others (Downs & Smith, 2004; Gadow et al., 2008; Ghaziuddin et al., 2002; Humphrey & Symes, 2010; Stewart et al., 2006; White & Roberson-Nay, 2009); and sensory differences that hinder sustained attention, as well as misunderstandings arising from difficulties understanding sarcasm, abstract terms and figures of speech (Bowen & Plimley, 2008). To target diminished Theory of Mind, a social story (Gray & White, 2002) is included to assist participants to understand the process of RAP-A-ASD and to introduce the facilitator. Computerised sessions (iRAP), using a visual medium to which young adolescents with autism respond well (Bowen & Plimley, 2008) were added to introduce the RAP model, present interactive exercises, and include prompts to engage participants and augment understanding of program content. To enhance communication, facilitators were instructed to provide clear instructions and concrete terms when communicating verbally, and to augment verbal communication with visual aids. To facilitate improved attention, the program was changed from a group to an individual format to reduce potential treatment interference from social demands; up to 14 one-on-one sessions (instead of 11) were allowed to provide the young adolescent with additional time to engage in the program content; facilitators were instructed to conduct sessions in a quiet space to minimise distractions, to incorporate the young adolescent’s special interests into sessions to increase their engagement, and to pause after asking question or watching a multimedia segment to allow the young adolescent to process the information and think about their response (Bowen & Plimley, 2008). Sessions cover rapport building; recognising strengths; promoting and regulating self-esteem; managing stress; cognitive restructuring; problem solving; developing a support network and help seeking; perspective taking and preventing and managing conflict.

RAP-A-ASD was trialled in a pilot RCT that aimed to reduce and prevent depression and improve self-efficacy in young adolescents on the spectrum with low support needs (Mackay et al., 2017). The RCT showed some initial evidence for promoting resilience by enhancing some protective factors for adolescents on the autism spectrum. Quantitative results showed significant intervention effects on parent reports of adolescent coping self-efficacy but no effect on depressive symptoms or emotional and behavioural functionality. Qualitative outcomes indicated potential improvements in affect regulation, and enhanced social communication and engagement skills. These are important findings given the increased tendency of young adolescents on the autism spectrum to experience intense emotions that they struggle to manage, and their difficulties with social interaction and communication that impact on forming and sustaining relationships (APA, 2013; Kanne, Christ, & Riersen, 2009; Konstantareas & Stewart, 2006; White & Roberson-Nay, 2009). Thus, the RAP-A-ASD program showed some initial evidence for promoting resilience through enhancing some protective factors for adolescents on the spectrum. However, the lack of a significant intervention effect for depression indicated that a multilevel trial that intervened at the adolescent, parent and school level was required to build more comprehensively the protective factors of school connectedness and self- and affect regulation in young adolescents on the autism spectrum to protect against the development of depression.

Resourceful Adolescent Program for Parents

RAP-P is a strength-based, non-blaming resilience-building program. It is based on an integration of cognitive-behavioural theory, Bowen Family Systems Theory (Kerr & Bowen, 1988; Titelman, 2014), and knowledge from developmental psychology of the maturational changes that occur naturally during adolescence. RAP-P promotes family-based factors that buffer adolescents from depression: age-appropriate secure attachment to parents, parental expressions of caring and warmth, and supporting adolescents to develop increasing autonomy (see Restifo & Bögels, 2009 for review). To achieve this, parents focus on their strengths, develop strategies to manage their stress, enhance their understanding of adolescent development (e.g. autonomy and attachment), and explore strategies for promoting family harmony and preventing and managing conflict. RAP-P is offered to all parents of young adolescents engaged in RAP-A, and is delivered over 3 2-h weekly workshops. A recent RCT of suicidal adolescents and their parents in an Australian outpatient clinic demonstrated that RAP-P may be particularly effective when used with selective populations to help parents to manage their stress and to maintain empathy for their adolescents in difficult circumstances. Post-treatment RAP-P was associated with improved parent- adolescent relationships and parental self- and affect regulation, greater reductions in adolescents’ suicidal behaviour, and greater reductions in adolescent psychiatric disability with gains maintained at 6-month follow-up (Pineda & Dadds, 2013).

RAP-P was adapted and manualised for parents of young adolescents on the autism spectrum. The Resourceful Adolescent Program for Parents of Adolescents with ASD (RAP-P-ASD; Shochet & Wurfl, 2016a, 2016b) has the same aims as RAP-P, and also aims to provide parents with greater levels of understanding and empathy for the developmental needs of adolescents on the spectrum. RAP-P-ASD includes additional material on managing stressors unique to parenting adolescents on the autism spectrum, parent activities to promote a sense of belonging in their adolescent, and exercises to highlight the opportunities for personal growth that arise from parenting an adolescent on the spectrum (drawing on the literature on post-traumatic growth). To make room for these additions, RAP-P-ASD has an extra session and consists of four 2-h workshops. The first session focuses on promoting parental self-efficacy, exploring the impact of stress on parents, and the efficacy of calm parenting. The second session addresses stress management for parents, adolescent development, and boosting adolescent self-esteem and a sense of belonging in the community and at home. The third session covers parents’ involvement in their developing adolescents’ lives, strategies for balancing adolescents’ striving for independence while strengthening parent-adolescent bonds, and promoting harmonious family relationships to diminish stress in the family system. The final session concentrates on preventing and managing parent-adolescent conflict so as to strengthen family connectedness, and reflecting on personal growth that can result from parenting an adolescent on the autism spectrum. Qualitative exploration of the experience of 15 parents who participated in RAP-P-ASD in 2016 revealed they were motivated to participate due to feeling isolated and unsupported by existing services, that they valued interacting with other parent participants, and that they experienced the program as enhancing their wellbeing and parenting efficacy, reducing their sense of isolation, increasing their ability to parent calmly, and improving parent-adolescent relationships (Shochet et al., 2019).

Resourceful Adolescent Program for Teachers

RAP-T is a program designed to assist teachers with the micro-skills to foster school connectedness. RAP-T aims to increase teachers’ recognition of the importance of school connectedness in educational functioning and mental wellbeing, provide resources and strategies for enhancing the key elements of school connectedness in teachers’ interactions with students, and help teachers to manage their own stress. RAP-T is delivered as a 2-h workshop with teachers and school personnel from schools implementing RAP-A. A pilot study of RAP-T with 70 teachers was well accepted, and participant evaluations were consistently high (Shochet & Ham, 2004).

RAP-T was adapted and manualised for teachers of adolescents on the spectrum. The Resourceful Adolescent Program for Teachers of Adolescents with ASD (RAP-T-ASD; Shochet & Wurfl, 2016c) includes additional information for teachers about the challenges that young adolescents on the autism spectrum encounter in secondary education, and the unique challenges that teachers of these young adolescents may encounter. It also discusses the importance of school connectedness for these young adolescents to support prosocial behaviour, academic success, emotional wellbeing and resilience; and provides practical strategies for promoting school connectedness, grouped within the key elements of school connectedness (warm relationships, student inclusion and a sense of belonging, the identification and encouragement of students’ strengths, and equity and fairness). RAP-T-ASD is augmented with the Index for Inclusion (Booth & Ainscow, 2011), a process that operates at the school systems level to support the development of a school culture, policy and practice that promotes school connectedness and inclusion.

The Integrated Model

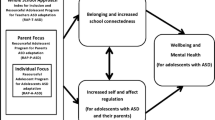

The conceptual Autism CRC model is a theoretically and empirically supported model to promote the mental wellbeing of young adolescents on the autism spectrum in schools (see Fig. 1 and Shochet et al., 2016 for detail). Based on this model, a multilevel, selective, evidence-based resilience intervention was designed to address the reciprocally related protective factors of self- and affect regulation and school connectedness to improve the wellbeing of adolescents on the spectrum. This multilevel resilience intervention is preventative in nature and targeted adolescents on the autism spectrum in South East Queensland schools using RAP-A-ASD, their parents using RAP-P-ASD, and their teachers and the school system using RAP-T-ASD augmented with the Index for Inclusion.

Source: Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature Customer Service Centre GmbH: Springer Nature, Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, The Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (Autism CRC) conceptual model to promote mental health for adolescents with ASD, Shochet et al., © 2016

The conceptual Autism CRC model for promoting mental health and wellbeing in young adolescents on the autism spectrum.

Using a mixed methods design, this project had two aims:

-

1.

The first aim was to determine whether operating at multiple ecological levels (adolescent, family and school) using a school-based intervention designed to increase the capacity for school connectedness and self- and affect regulation in young adolescents on the autism spectrum was feasible and could result in a sustainable, primary prevention program. It was hypothesised that the multilevel resilience intervention would be implemented with integrity and fidelity within the school setting, and would be accepted by participants.

-

2.

The second aim was to ascertain whether this multilevel resilience intervention would improve the wellbeing and mental health of young adolescents on the autism spectrum by increasing their resilience. The quantitative component aimed to examine whether a reliable improvement could be realised in:

-

3.

depressive symptoms measured using the CDI 2 (Kovacs & MHS Staff, 2011),

-

4.

anxiety measured using the Anxiety Scale for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASC-ASD; Rodgers et al., 2016),

-

5.

behavioural and emotional difficulties measured using the SDQ (Goodman, 1997),

-

6.

sense of school connectedness measured using the PSSM (Goodenow, 1993), and

-

7.

coping self-efficacy measured using the CSES (Chesney et al., 2006).

It was hypothesised that, as a result of participating in the multilevel resilience intervention, the young adolescents would realise a reliable improvement in depressive symptoms, anxiety, behavioural and emotional difficulties, sense of school connectedness, and coping self-efficacy.

The qualitative component aimed to probe the experience of the young adolescents and their parents. It was hypothesised that the experience of the young adolescents and their parents would further inform the role the multilevel resilience intervention played in promoting protective factors to improve the wellbeing and mental health of young adolescents on the autism spectrum.

Methods

Study Design

A 3-year multisite proof-of-concept study using a mixed methods longitudinal design was used to pilot and evaluate the multilevel resilience intervention. Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data from young adolescents (referred to as students from hereon), and their caregivers or parents (referred to as parents from hereon) was employed to validate findings and answer the research questions (Guion, 2002; Palinkas, Horowitz, Chamberlain, Hurlburt, & Landsverk, 2011). Primary quantitative outcomes were depressive symptomology, emotional and behavioural functionality, coping self-efficacy, degree of school connectedness, and anxiety levels at pre-intervention; post-intervention; and 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up. Qualitative data tapping participants’ experience was collected from students after they completed RAP-A-ASD and at 3-month and 12-month follow-up; from their parents post RAP-A-ASD implementation and at 12-month follow-up; and post-implementation from parents who participated in RAP-P-ASD.

Participants

The study was conducted in 6 secondary schools in Brisbane, Australia, an urban city with a population of approximately 2.3 million. Participants included students (n = 30) enrolled in the first two years of a participating secondary school (Years 7 and 8) who had a diagnosis from a paediatrician or psychiatrist of Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or Persistent Developmental Disorder not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) as per the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) as per the DSM 5 (APA, 2013); their parents (n = 31); teachers closely involved with the students (n = 16), and school staff who helped to implement the Index for Inclusion (n = 35). As RAP-A-ASD aims to prevent depression, students were not required to be clinically or sub-clinically depressed to participate. Individuals with intellectual impairment (diagnosed by a paediatrician or psychiatrist—typically a Full Scale Intelligence Quotient below 70), severe behavioural difficulties that would preclude the student’s ability to engage one-on-one with a facilitator for 50 min (as judged by the student’s Head of Special Education) or psychosis were excluded, given the cognitive and behavioural demands of the program. Thirty-one students commenced the RAP-A-ASD program but one student opted out after completing 3 sessions and did not complete any measures, so was excluded from the analyses, yielding a final sample of 30 students (24 male, 6 female; aged 11 to 14 years (Mage = 11.84; SDage = 0.86). Students came from lower and middle class families, and, consistent with data showing that autism is diagnosed four times more frequently in males (APA, 2013), there were more male than female participants. The 30 students who completed RAP-A-ASD had a primary diagnosis of ASD (n = 18, 60%), Asperger’s Syndrome (n = 10, 33.3%), Autistic Disorder (n = 1, 3.3%) or PPD-NOS (n = 1, 3.3%); and 18 (58.1%) had one or more comorbid diagnoses including Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (n = 11, 36%), anxiety (n = 8, 26%), Auditory Processing Disorder (n = 3, 10%), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (n = 2, 6.6%), Sensory Processing Disorder (n = 2, 6.6%) or Tourettes (n = 2, 6.6%). For each student, a parent (n = 30) completed questionnaires and participated in semi-structured interviews about their experience of their child. Thirty-one parents of 23 students, representing 77% caregiver involvement (20 mothers, 7 fathers, 1 grandmother, 1 stepmother, 1 foster mother, and 1 foster father) availed themselves of the opportunity to participate in RAP-P-ASD. Parent attendance of the RAP-P-ASD workshops was moderate (32% attended all 4 workshops, 29% attended 3 workshops, 16% attended 2 workshops, and 23% attended only 1 workshop). Teachers at 5 of the 6 participating schools attended a RAP-T-ASD workshop facilitated by the research team.Footnote 2 To implement the Index for Inclusion, the research team formed a School Connectedness Committee at each participating school that consisted of principals, special education and classroom teachers, student leaders, project researchers, and parents (see Carrington et al., 2021).

Measures

Children’s Depression Inventory 2 (CDI-2; Kovacs & MHS Staff, 2011)

The CDI-2 assesses severity of childhood depressive symptoms and demonstrates good test–retest reliability and internal consistency (α = 0.86; Kim et al., 2018). The student CDI-2 includes 28 items that present participants with three sentences (e.g. ‘I am sad once in a while’, ‘I am sad many times’, ‘I am sad all the time’) and instructs them to choose the sentence they most identify with. Each sentence is scored from 0 to 2 and items are summed to produce a total score. The item screening for suicidal ideation was excluded in this study, resulting in 27 items with a possible total score of 54. Higher scores indicate greater severity of depression symptoms. The parent CDI-2 has 17 items measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (much or most of the time). Cronbach’s alphas at baseline displayed good reliability (students α = 0.89; parents α = 0.87).

Anxiety Scale for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASC-ASD; Rodgers et al., 2016)

The ASC-ASD is a 24-item measure of anxiety designed for young people (8–16 years old) on the autism spectrum and their parents. Participants respond using a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Scores are summed, with totals ranging from 0 to 72. The ASC-ASD demonstrated good reliability among students (α = 0.84) and parents (α = 0.93) at baseline in the current study.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997)

The SDQ taps child and adolescent wellbeing by measuring behavioural and emotional difficulties across 25 items scored on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (certainly true). Four SDQ subscales (emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems) are combined to create a total difficulties score. Student responses yielded acceptable Cronbach’s alpha scores at baseline for the total difficulties subscale (students α = 0.84). Cronbach’s alpha scores at baseline for parent responses about their adolescents’ internalising behaviours were acceptable (parents α = 0.71) but were questionable for their externalising behaviours (parents α = 0.67), resulting in the total difficulties subscale falling in the questionable range (parents α = 0.67) and making outcomes more conservative.Footnote 3

Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (PSSM; Goodenow, 1993)

The PSSM is an 18-item measure of students’ perception of their belonging at school (i.e. school connectedness). Participants respond to item statements (e.g. ‘I feel like a real part of [school name]’) on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (completely true). Five negatively scored items are inverted and higher summed scores indicate a greater sense of school membership. The PSSM demonstrates good reliability (α = 0.78–0.95; You et al., 2011). Acceptable Cronbach’s alpha scores were seen at baseline (students α = 0.86, parents α = 0.84).

Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES; Chesney et al., 2006)

The CSES is a 26-item measure of one’s confidence in performing coping behaviours when faced with life challenges and demonstrates high reliability (α = 0.95; Chesney et al., 2006). This study adapted the CSES to suit young adolescents with autism by using more literal language (e.g. the item, ‘Resist the impulse to act hastily when under pressure’ was replaced with ‘Stop yourself from acting too quickly when under pressure’). Participants respond to item statements on an 11-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (cannot do at all) to 10 (certain can do). Scores are summed, with higher results showing a greater degree of self-efficacy to cope under duress. The CSES Cronbach’s alpha displayed excellent reliability at baseline (students α = 0.91, parents α = 0.97).

Process Evaluation Scale

Participants completed a 15-item process evaluation scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never/not at all useful) to 5 (all the time/very useful) at the end of the RAP-A-ASD intervention. Items tapped participant satisfaction with the program.

Procedure

Ethics and Informed Consent

Approval to conduct the project was obtained from the Queensland University of Technology’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 1500000156). At study commencement all participants received a participant information sheet. At each time point parents provided written consent to participate in the study and provided written consent for their child to participate, and students provided written assent. Parents also provided consent for parent and child interviews to be audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed post de-identification. Participants generated a unique code used for all surveys.

Program Implementation

At the student and parent levels, the RAP-A-ASD and RAP-P-ASD programs were implemented by trained facilitators over 2 years in the second and third terms of the Australian school year (i.e. April to September 2016 and 2017). Facilitators delivered RAP-A-ASD by following the session content and process described in the RAP-A-ASD Group Leader’s Manual (Shochet & Wurfl, 2019a). Each student received a RAP-A-ASD Participant Workbook (Shochet & Wurfl, 2019b). RAP-A-ASD sessions were conducted one-on-one with a facilitator and student during a non-core lesson in the school day in a room separate to the classroom to facilitate discussion and minimise distractions. There were 11 50-min weekly sessions which could be extended to 14 sessions to provide students with additional time to engage in the program content. Facilitators completed an integrity checklist after each session, and discussed session process and their checklist responses in weekly supervision with a member of the Research Team to ensure internal validity and assess adherence to the treatment manual (Mowbray et al., 2003). Students completed the process evaluation scale after their final RAP-A-ASD session. RAP-P-ASD was delivered over 4 weekly 2-h workshops. Separate RAP-P-ASD workshops were conducted for each participating school. Facilitators delivered RAP-P-ASD by following the session content and process described in the RAP-P-ASD Group Leader’s Manual (Shochet & Wurfl, 2016a), and each parent participant received a RAP-P-ASD Participant Workbook (Shochet & Wurfl, 2016b). At the school level, the RAP-T-ASD program was delivered according to the RAP-T-ASD Group Leader’s Manual augmented with additional material specific to working with students on the autism spectrum (Shochet & Wurfl, 2016c) as an optional, single 2-h workshop at each of the participating schools to provide training to assist teachers, administrators and support staff to promote school connectedness. To implement the Index for Inclusion, the School Connectedness Committee formed at each participating school in the first term of the school year identified, implemented and evaluated a project to increase school connectedness (see Carrington et al., 2021).

Data Collection

Quantitative data were collected from students and parents using an online survey, or paper survey when technical difficulties were experienced, at five time points: (T1) Pre: prior to student participation in RAP-A-ASD (T2) Post-implementation: after the final session of RAP-A-ASD; (T3) 3-month follow-up; (T4) 6-month follow-up; and (T5) 12-month follow-up. Students and parents completed measures that tapped students’ depressive symptoms, anxiety levels, behavioural and emotional difficulties, sense of school connectedness, and confidence to use coping behaviours in times of stress. Survey completion rates were good, with 100% completion by students and parents at T1, reduced to 73% and 60% completion by students and parents, respectively, by T5.

A research assistant not involved in the delivery of RAP-A-ASD and RAP-P-ASD conducted digitally recorded qualitative semi-structured interviews with participants. Qualitative data was collected from students at school post-implementation, and at 3-month and 12-month follow-up, in face-to-face interviews lasting an average of 10 min. Questions tapping domains relating to participants’ experience of the program, their memory of concepts and strategies that they learned and instances when they used these, and changes they had noticed in themselves and in others were asked. Qualitative data was collected from parents in telephone interviews lasting an average of an hour after their adolescents completed RAP-A-ASD, and at 12-month follow-up. In addition, parents who participated in RAP-P-ASD were interviewed at the end of the year in which they attended the workshops (see Shochet et al., 2019). All digital audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by an external transcriber. Transcriptions were checked against the recordings by an independent researcher to ensure accuracy before de-identifying data for analysis.

Data Analysis

The quantitative analysis used an idiographic approach, focusing on within-participant change and each individual’s response to the RAP-ASD program rather than analysing aggregate data. Individual scores obtained from administering the CDI-2, ASC-ASD, SDQ, PSSM, and CSES measures at post-implementation, 3-month, 6-month and 12-month follow-up were compared to baseline scores using the Reliable Change Index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax, 1991). Reliable change analysis calculates a standardised score of an individual’s change over time and determines its statistical significance, is considered to be a conservative estimate of ‘true change’ when using self-report measures, and works well when measuring individual outcomes in small samples (Ferguson et al., 2002; Zahra & Hedge, 2010). The RCI cutoff represents the amount of change required to be 95% certain that change was not due to measurement error or chance. The reliable change analysis was calculated separately for student and parent reported data.

Qualitative data from students and parents were analysed using Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR; Hill, 2012) which enables in-depth analysis of data obtained using open-ended questions in semi-structured interviews to identify individuals’ experiences. Four project team researchers categorised data into domains (broad topic areas), core ideas (summaries of what participants said within each domain), and common themes (summaries of participants’ statements which occur within a core idea within a domain) in an iterative process until consensus was reached. Following, common themes were quantified by tallying two scores that indicated common themes’ relative importance within each core idea: unweighted scores indicated the number of transcripts in which the theme appeared, and weighted scores indicated the number of instances where the theme appeared (including multiple appearances within a transcript). An external auditor provided feedback during each stage of the CQR process to identify and overcome group bias; ensured all important raw data was extracted and allocated to the correct domain, core idea, and common theme; determined that core idea wording was true to the raw data; and checked accuracy of unweighted and weighted scores.

Results

Program Fidelity

To ensure internal validity and assess adherence to the RAP-A-ASD manual, facilitators completed an integrity checklist after each RAP-A-ASD session by rating completion of session components on a 3-point scale (0 = no, 1 = somewhat, and 2 = yes), and participant engagement and usefulness of session components on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all) to 5 (very). The mean student completion, engagement and usefulness scores were divided by the number of students and converted to a program completion percentage (87.27%), an engagement percentage (84.66%), and a usefulness percentage (85.82%). These percentages indicated that the manual was implemented consistently, and that participants were engaged and found the program useful.

Process Evaluations

Students’ mean rating for core aspects of the RAP-A-ASD program fell in the very useful range (M = 4.13, range 3.90–4.31) and their overall rating of the program was very positive (M = 4.62, range 2–5). Participants indicated that they looked forward to coming to sessions (M = 4.45, range 2–5), and that involvement in RAP-A-ASD had value in their everyday life (M = 3.93, range 3–5) and helped them to feel more positive about life (M = 3.86, range 2–5), supporting the strength-based nature of the program and its aim of promoting wellbeing. However, participants indicated that they were less likely to discuss their involvement in the program with their parents (M = 3.57, range 1–5) or peers and siblings (M = 2.65, range 1–5), and that they had received little feedback about changes noticed in them since starting RAP-A-ASD from parents (M = 2.60, range: 1–5) or teachers and peers (M = 2.46, range 1–5).

Descriptive Statistics

Student and parent descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Student CDI-2 scores were classified according to age and gender, with scores in the high average and elevated range denoting subclinical depression, and scores in the very elevated range denoting clinical depression (Kovacs & MHS Staff, 2011). ASC-ASD total scores of 20 or more indicated clinically significant levels of anxiety, and scores below 20 indicated average levels of anxiety (Rodgers et al., 2016). Total difficulty (SDQ-TD subscale) cut-offs were student (average: 0–15, subclinical: 16–19, clinical: 20–40), and parent (average: 0–13, subclinical: 14–16, clinical: 17–40) (Youth in Mind, 2012). Table 2 shows the distribution of students’ scores across clinical categories, with pre-intervention scores showing that over a quarter were clinically depressed and close to a third were sub-clinically depressed; that a significant majority reported clinically significant levels of anxiety; and over half reported internalising and externalising difficulties in the clinical range.

Statistical Analysis of Quantitative Data

RCI was calculated by subtracting a pre-intervention score from a post-intervention score (post-implementation, 3-month, 6-month, or 12-month) and dividing the result by the standard error of difference.

The standard error of difference represents the estimated distribution of outcomes if no change occurred. It is calculated using the baseline standard deviation and Cronbach’s alpha of each measure.

As RCI focuses on individual patterns of change, missing data was managed by excluding the participant outcome at the time point where data was missing (Jacobson & Traux, 1991; Lewis et al., 2007). Change was considered statistically significant when the Z score exceeded 1.96 (resulting in significance of p < 0.05). Direction of change was inverted for the CDI-2, ASC-ASD, and SDQ-TD so the direction of improvement or deterioration would be consistent across all scales. Higher values indicated improvement across all measures and lower values indicated deterioration. For scales with clinical cutoffs derived from normed data (i.e. the CDI-2, ASC-ASD, and SDQ-TD), clinically significant change was calculated and was defined as movement from one clinical group to another (Goodman, 1997; Kovacs & MHS Staff, 2011; Rodgers et al., 2016).

Student Reported Outcomes

Table 3 displays the directionality of each student’s RCI for each measure at all time points. Table 4 summarises the statistical and clinical change results across the whole sample.

Statistically Reliable Change

Tables 3 and 4 show that the greatest amount of reliable improvement was seen across measures of anxiety, total difficulties, psychological sense of school membership, and coping self-efficacy, with particularly high percentages of improvement reported at 3-month follow-up. While improvement in anxiety and total difficulties seemed to peak at 3-month follow-up with smaller numbers reporting improvements at other time points, improvements in psychological sense of school membership and coping self-efficacy were maintained across the 12-month period. Prevalence of improvement in depressive symptoms increased between post-implementation and 3-month follow-up, and remained stable for the rest of the study. The majority of students reported change that was not statistically significant across all measures at most time points. While a small number of students reported significant deterioration across all measures for at least one time point, deterioration across all measures had reduced to below 5% of students by 12-month follow-up. For depression, anxiety, and total difficulties, the greatest increase in deterioration occurred post-implementation; while the deterioration in coping self-efficacy peaked at 3-month follow-up, and the deterioration in psychological sense of school membership peaked at 3-month and 6-month follow-up.

Clinically Significant Change

All students with statistically reliable change scores for depression (CDI-2) and total difficulties (SDQ-TD) showed clinically significant improvements. Only 1 of 5 students showing improvement in anxiety symptoms (ASC-ASD) at post-implementation reported a clinically significant improvement; however improvement increased dramatically by 3-month follow-up where all 14 students with statistically reliable improvement reached clinical improvement. An additional 11.11–28.57% of students reported clinical improvements in depression, anxiety or total difficulties across the four post-implementation timepoints (e.g. shifting from clinical to subclinical, or subclinical to average), despite not showing statistically reliable change. All but one student (who was classified as clinically depressed at baseline, so deterioration did not create a clinically significant change from one category to another) with depression change scores showing statistically reliable deterioration showed clinically significant deterioration. Statistically reliable deterioration for total difficulties was also clinically significant for all affected students. Both students reporting statistically reliable deterioration in anxiety at post-implementation showed clinically reliable deterioration, moving from average to clinical classification. All other significant RCI scores were for students reporting clinical anxiety symptoms at baseline, and deterioration was not associated with change in clinical classification.

Parent Reported Outcomes

Student self-reported data were complemented with parent reported data on all measures. Table 5 displays the direction of change for parent reported RCI results for each student, and Table 6 provides a summary of the statistically and clinically significant changes for each measure.

Statistically Reliable Change

Tables 5 and 6 show that the majority of parents reported change that was not statistically significant across all measures at most time points, with the exception of coping self-efficacy which was equally distributed across improvement, deterioration, and no change. The largest percentages of parent reported reliable improvement were seen for depression (27.78%), anxiety (38.89%), school connectedness (25.00%), and coping self-efficacy (33.33%). Coping self-efficacy appeared to have the most stable levels of improvement across all time points, while improvements for depression, anxiety, and total difficulties appeared to drop at 3-month follow-up and then peak at 12-month follow-up. Parents reported very small numbers of significant deterioration across most measures and time points. The exception was for coping self-efficacy, where between a fifth and a third of parents reported deterioration in their children, with the highest deterioration reported at 3-month follow-up and the lowest reported at 12-month follow-up.

Clinically Significant Change

Most parents reporting statistically reliable improvement in their child’s depression or anxiety saw a clinically significant improvement. The remaining cases were for children whose parents reported their child’s depression or anxiety as average at baseline, hence improvement in symptoms was more protective than clinically significant. All parent reports of statistically reliable change in total difficulties across each time point were clinically significant. Across all three measures, statistically and clinically significant improvement at post-implementation appeared to dip at 3-month follow-up before equalling or exceeding post-implementation scores by 6-month and 12-month follow-up. Across each measure and time point, an additional 4.17–38.89% of parents reported clinical improvements in their child (e.g. shifting from clinical to subclinical, or subclinical to average); however the change did not reach statistical significance. Overall, a smaller percentage of parents reported statistically reliable deterioration in their child’s depression or anxiety symptoms. Only one parent reporting statistically reliable deterioration in depression also saw a clinically significant deterioration, with depression moving from average at baseline to the subclinical range at 6-month follow-up. The three other parents reporting statistically reliable deterioration in depression reported clinical levels of depression for their child at baseline; therefore the deterioration across the four subsequent time points did not cross any clinical cutoffs to classify as clinically significant. One parent reporting statistically reliable deterioration in their child’s anxiety at post-implementation, and both parents reporting statistically reliable deterioration at 6-month follow-up reported clinically significant deterioration.

Analysis of Qualitative Data

The coder inter-rater reliability was highly satisfactory (Orwin & Vevea, 2009): the mean kappa coefficient was 0.96 (range: 0.74 – 1.0) and the mean intraclass correlation was 0.99 (range 0.99 – 1.0). The very high intraclass correlation was not surprising given the consensual, iterative approach adopted by the CQR approach. Qualitative analysis of data from student interviews identified five domains containing 14 core ideas and 38 common themes presented in Tables 7 to 11 (see Online Resources). The weighted quantitative score provides an indication of the relative importance of themes within each core idea, hence themes are presented in rank order, with those having the highest weighted score at the top of the list within each core idea, and those with the lowest weighted score at the bottom of the list within each core idea. The unweighted quantitative score reflects the number of participants whose feedback supported a theme. In the first domain, aspects of participation that students liked (see Table 7 in Online Resource), students highlighted their experience of RAP-A-ASD as enjoyable (e.g. “I was looking forward to going [each week]”), and supportive (e.g. “the people who helped … with the RAP program … were very supportive”). In the second domain, aspects of participation that students experienced as beneficial (see Table 8 in Online Resource), students remarked that participation had been a positive experience (e.g. “Everything we did there was helpful”), and detailed numerous aspects of the program that had stood out for them, (e.g. “bricks with suggestions of how to cope … how to relax … strength stuff … the diagram with the self-talk, behaviour and body clues … perspectives and seeing other people’s … point of view”). In the third domain, students’ experience of becoming more resourceful as a result of participating in RAP-A-ASD (see Table 9 in Online Resource), students reported positive changes they had noticed in themselves (e.g. “I actually carry the RAP [wallet card] around … it just reminds me of [what I learned]”), and ways in which they were applying knowledge and skills acquired in the program (e.g. “A girl in my maths class [is] bullying me about my autism… I … asked the teacher if I could be moved … normally I would have retaliated by saying … something really offensive back”). In the fourth domain, aspects of participation that students experienced as challenging (see Table 10 in Online Resource), challenges mentioned most frequently included practical challenges (e.g. “Writing things down … my hand got tired”), and difficulty remembering content (e.g. “I’ve got the worst memory”). In the fifth domain, students’ suggestions for enhancements to RAP-A-ASD (see Table 11 in Online Resource) included increased contact (e.g. “Are you guys doing it again next year? Cause I wouldn’t mind doing it again”), reduced reading and writing (e.g. “Not do as much of … the book work”), and personalising the program (e.g. “tailor it a little bit more to what people actually need”).

Also, CQR analysis was conducted using interview data from 15 parents who participated in the 2016 RAP-P-ASD workshops. Parents’ intervention experience is reported elsewhere (see Shochet et al., 2019). Exploration of qualitative data from the 2017 RAP-P-ASD participants indicated that saturation had been reached. In summary, parents who participated in RAP-P-ASD reported that doing so helped with their sense of isolation and validated their parenting difficulties; increased their parenting efficacy by affirming their existing strengths; increased their confidence to be non-reactive and calmer in their parenting; increased their empathy for, and understanding of, their adolescent; improved their communication with, and sense of connectedness to, their adolescent; increased their understanding of a more optimal way to assist their child to navigate early adolescence; and increased their wellbeing by enabling them to manage family conflict in a more adaptive manner.

Discussion

This mixed methods proof-of-concept longitudinal study validated the conceptual Autism CRC model designed to promote the mental health of young adolescents on the spectrum (Shochet et al., 2016) by developing, implementing and evaluating a multilevel resilience intervention promoting a greater ability to regulate emotions and improved relationships at the early adolescent, family and school levels. The study yielded a prototype of the multilevel resilience intervention. Favourable feedback from participants and facilitators, along with high adolescent and school participation rates, and moderate parent participation rates across the three levels of the intervention over 2 years, indicated that this framework can be integrated in the school culture and implemented in the school environment as a sustainable, primary prevention program. Furthermore, promising findings from triangulated quantitative and qualitative data from students and their parents showed some evidence for promoting resilience by enhancing protective factors for adolescents with a diagnosis or traits of autism, their parents, and in their schools. Hence, it appears that the school-based, strength-focused multilevel resilience intervention offers a feasible, sustainable and promising primary prevention program for promoting mental health in young adolescents on the autism spectrum.

Feasibility and Sustainability of the Multilevel Resilience Intervention

The study’s first aim was to determine whether operating at multiple ecological levels (student, family and school) using a school-based multilevel resilience intervention ((RAP-A-ASD, RAP-P-ASD, and RAP-T-ASD; Shochet & Wurfl, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2019a, 2019b) in conjunction with the Index for Inclusion (Booth & Ainscow, 2011)) designed to increase the capacity for school connectedness and self- and affect regulation in young adolescents on the spectrum was feasible and could result in a sustainable, primary prevention program. In line with the hypothesis, the multilevel resilience intervention was implemented with integrity and fidelity within the school setting, and was accepted by participants. Thirty students (97%) completed all 11 sessions of RAP-A-ASD across 2 school terms. Integrity checklists completed by session facilitators after each session showed that the RAP-A-ASD program was implemented with fidelity by facilitators, and was accepted by the student participants. The process evaluations completed by students after their final RAP-A-ASD session showed that they experienced RAP-A-ASD as very useful, enjoyable, and relevant in their everyday life, supporting the strength-based nature of the program and its aim of promoting wellbeing. In addition, 31 parents of 77% of the student participants attended some or all of the resilience building RAP-P-ASD workshops. They reported that they were seeking knowledge-based and emotional parenting support that was unmet by existing parenting services, and that they experienced the strength-based program as enhancing their mental wellbeing and parenting efficacy. At the school level, teachers at 5 of the 6 participating schools attended a 2-h RAP-T-ASD workshop; and a School Connectedness Committee was formed at each participating school, and successfully used the Index for Inclusion to identify, implement and evaluate a project in their school community during the school year to increase school connectedness (see Carrington et al., 2021). Anecdotal evidence suggests that high recruitment, engagement, and retention of participants across the three levels of the intervention was due in part to the strength-focused narrative of RAP which provides the prospect of mental health promotion that aims to minimise or avoid stigma or labelling.

In recognition of the need to intervene in childhood to promote mental health and wellbeing throughout the lifespan, the Australian Government launched the National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy in October 2021 (National Mental Health Commission, 2021). The strategy acknowledges the essential role that schools play in children’s mental health and wellbeing, accepts that the manner and extent to which schools fulfil this role varies widely, and endorses schools using evidence-based programs to improve the mental health and wellbeing of children, their families, and the communities that support them. The manualised format of RAP-A-ASD, RAP-P-ASD and RAP-T-ASD facilitates their ongoing delivery by school staff who have been trained to deliver these programs, and a member of the school leadership team can initiate and oversee the implementation of the Index for Inclusion. Hence, it appears that the school-based strength-focused multilevel resilience intervention can be embedded in the school culture, and accepted in the school environment as a sustainable, primary prevention program for promoting mental health in young adolescents on the spectrum.

Impact of the Multilevel Resilience Intervention

The study’s second aim was to ascertain whether this multilevel intervention would improve the wellbeing and mental health of young adolescents on the autism spectrum by increasing their resilience. The quantitative component examined whether a reliable improvement in depressive symptoms, anxiety, behavioural and emotional difficulties, sense of school connectedness, and coping self-efficacy could be realised. The qualitative component probed the experience of students and their parents to further inform the role the intervention played in promoting protective factors to improve the wellbeing and mental health of young adolescents on the spectrum.

Students’ Positive Experience of Participating in RAP-A-ASD

Overall, the triangulated quantitative and qualitative outcomes from the majority of students showed an increase in resilience, as reflected in improvements in the protective factors of coping self-efficacy, self-regulation (behavioural and emotional functioning), affect regulation in the form of increased control over anxiety, and a sense of belonging in the form of school connectedness. Reliable change analysis revealed the greatest amount of student reported change for coping self-efficacy, anxiety, emotional and behavioural difficulties, and school connectedness, with particularly high percentages of improvement reported at 3-month follow-up. Importantly, the statistically significant change was frequently found to be clinically significant, concretising the statistical improvements as having a real impact on student wellbeing and mental health.

Consistent with documented individual-level change in youth depression treatment outcomes in real-world settings from 1980 to 2019, synthesised in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis (pooled sample N = 11,739, Mage = 13.8 years; Bear et al., 2020), the improvement in depressive symptoms was more modest. A minority of adolescents (13%) and parents (30%) reported a reliable improvement in depressive symptoms in the post-intervention to 12-month follow-up period. Bear and colleagues suggest that the more modest outcomes achieved in non-experimental settings with real-world populations may be attributed to factors such as comorbidity, medication use, treatment dosage, the episodic nature of depression that can impact on outcomes regardless of treatment exposure, the greater challenge of treating young adolescents compared to treating adults, and the greater complexity of the problems of these young adolescents. These factors applied to many of the adolescents in the current study. A majority (58.1%) had comorbid diagnoses and many were taking psychotropic medication to reduce difficulties associated with autism and comorbid conditions. This may have interfered with their ability to engage in the program and integrate its content in their everyday lives. In addition, it became apparent during the delivery of the multilevel resilience intervention that many students lived in complex family systems that were experiencing substantial stress which may indicate that the dose of the intervention in this study was insufficient for a subgroup of students. Also, that some of students struggled to remember the content of the program may partly explain why some students who initially reported a significant improvement did not maintain this improvement over the 12 months of the study.

Students, reflecting on changes noticed in themselves after participating in RAP-A-ASD, reported increases in resilience, confidence in managing their emotions and keeping calm, confidence in dealing with social situations, confidence in problem solving, and ability to consider others’ perspectives. They also remarked on valuing the experience of their facilitator as interested in and supportive of them. Student qualitative reports of increased coping self-efficacy suggested that they had recruited behavioural and cognitive strategies acquired from RAP-A-ASD (e.g. “the RAP program helped with … identifying what can help”, “the RAP program helped me to cope …”, “ [I] got better at … problem [solving and] not giving up”). Similarly, their reports suggested the use of the RAP-A-ASD components of managing stress and cognitive restructuring to assist with anxiety (e.g. “[I used strategies to] keep calm – like deep breaths”, “I was really nervous … I had to think … ‘it’s just a test … I have done really well in Science already … the [thought court] cards … showed … me that it’s not that big a deal”). Students’ feedback about their experience of becoming more resourceful as a result of participating in RAP-A-ASD, as reflected in the themes of improved self-regulation, suggested that they employed RAP-A-ASD strategies for managing anger and/or conflict, and the use of communication to improve emotion regulation (e.g. “It helped me … calm down a bit”, “It helped when I talked to my Mum [about my feelings …]”. Some students’ qualitative reports suggested a reduction in depressive symptoms (e.g. “I’m generally a bit more positive”, “I’ve just noticed myself being a bit happier”). That only a few students reported an improvement in depressive symptoms is consistent with prior research, and may be attributable to the expression of autism symptoms which can limit insight into depressive symptoms, reduce motivation to engage with assessments, increase concrete interpretation of questions, and encourage under reporting (e.g. Mackay et al., 2017; Mazefsky et al., 2011; Storch et al., 2012).

Parents’ Positive Experience of their Adolescents who Participated in RAP-A-ASD

Parents were less likely than their adolescents to report positive changes in their children’s mental wellbeing. It is possible that the additional challenges parents experience when parenting an adolescent on the autism spectrum compared to the challenges encountered when parenting adolescents not on the spectrum (see Shochet et al., 2019) may have obscured or delayed parents noticing their adolescents’ sense of their improvement. Parents, reflecting on changes they had noticed in their children as a result of their participation in RAP-A-ASD, most frequently identified diminished stress in the family system which they attributed to reduced conflict, feeling more connected to their adolescent, improvements in their adolescents’ emotion regulation, and enhanced parent-adolescent communication (see Shochet et al., 2019).

Reliable change analysis revealed that the majority of parents reported change that was not statistically significant across all measures at most time points, with the exception of coping self-efficacy which was equally distributed across improvement, deterioration, and no change, and appeared to have the most stable levels of improvement across all time points. The improvement in coping self-efficacy mirrors the findings of a pilot RCT of RAP-A-ASD that found significant intervention effects on parent reports of adolescent coping self-efficacy post-intervention and at 6-month follow-up, triangulated with qualitative findings from students, parents and teachers that endorsed this finding (see Mackay et al., 2017). In the current study, triangulated quantitative and qualitative results from students and parents provided convergent support for the important finding of students’ increased coping self-efficacy. Given the difficulties with coping strongly exhibited by people with autism (Dalton et al., 2005; Jahromi et al., 2012; Konstantareas & Stewart, 2006), it is encouraging that there may be a mental health promotion framework to support greater coping which is a known protective factor for depression and anxiety.

Deterioration in Mental Health Reported for a Minority of Students

Some students and parents reported worse outcomes at some time points. As discussed previously, factors such as comorbidity, side effects of medication, the episodic nature of depression, and complex individual and systemic problems experienced by the participants may have impeded their improvement. Notwithstanding, at 12-month follow-up, reliable deterioration from student reports had reduced to 0% for depressive symptoms, anxiety, behavioural and emotional difficulties, and coping self-efficacy, and to 4.6% for school connectedness. This finding is important and promising in the context of prevention as it demonstrates that students did not appear to experience the same level of deterioration in mental health at final follow-up that is often reported in other real-world studies of clinical and non-clinical samples of neurotypical young adolescents. The aforementioned synthesis of individual-level change in youth depression treatment outcomes found that 6% of young adolescents reliably deteriorated (Bear et al., 2020), and large trials in the United Kingdom found that 9–12% of adolescents reliably deteriorated (Warren et al., 2010; Wolpert et al., 2016, 2020). It is possible that the multilevel, strength-focused, resilience building features of RAP-ASD are responsible for this promising finding.

Parents’ Experience of Participating in RAP-P-ASD

Parents who participated in RAP-P-ASD reported that feeling isolated and unsupported by existing services motivated their participation, and that they valued interacting with other participants. They reported that the program enhanced their wellbeing and parenting efficacy, reduced isolation, increased their ability to parent calmly, and improved parent-adolescent relationships (see Shochet et al., 2019 for detail).

Overall, the triangulated quantitative and qualitative outcomes from students and their parents showed an increase in resilience, as reflected in increased coping self-efficacy, increased control over anxiety, diminished behavioural and emotional difficulties, and increased school connectedness. The reduction in depressive symptoms was more modest but was consistent with the individual-level change in youth depression treatment outcomes in real-world settings from 1980 to 2019 (Bear et al., 2020). These outcomes provide some evidence for the multilevel resilience intervention as an effective intervention that protects against declining wellbeing and mental health in this vulnerable population.

Strengths

The current study yielded a prototype of a multilevel resilience intervention that consisted of RAP-ASD (RAP-A-ASD, RAP-P-ASD, and RAP-T-ASD), a tailored prevention program designed and implemented among young adolescents on the autism spectrum based on more than 20 years of research demonstrating that increasing school connectedness can improve mental health and wellbeing among adolescents (Mackay et al., 2017; Shochet et al., 2001, 2006, 2008), and the Index for Inclusion (Booth & Ainscow, 2011). It was encouraging to discover that a school-based resilience intervention could be implemented with good validity and high acceptability. Employing a mixed methods research design to capture student and parent quantitative data obtained using validated measures, and qualitative data obtained from semi-structured interviews, facilitated triangulation of data about student mental health and wellbeing after the implementation of the RAP-ASD program and across the subsequent 12 months that provided convergent support for the multilevel resilience intervention as a feasible and sustainable, primary prevention program for promoting mental health in young adolescents on the spectrum. Further, the successful implementation of projects to increase school connectedness in all participating school communities suggests that the Index for Inclusion framework can play a critical role in supporting school connectedness and should continue to be implemented in schools.

Limitations

As this was a proof-of-concept study that implemented a manualised program and measured outcomes using self-report measures, the study design limitations of a lack of a control group, non-blinded procedure, and self-report bias need to be acknowledged. The multilayered design of the resilience intervention means that it is not possible to disaggregate the effects on student wellbeing and mental health at each level. Findings from this proof-of-concept study reflect the experience of a sample of students on the spectrum and their parents in urban Australia, with generalisability reduced by its relative homogeneity. While a potential for bias in the qualitative findings needs to be acknowledged, and findings were not checked by parent participants, so it is unknown whether they agreed with the analysis, to counteract this limitation, contrasting responses and alternative viewpoints were highlighted in the data analysis, and an external rater reviewed the data and validated findings. Furthermore, to reduce the load on school staff, qualitative data on feasibility and acceptability was not collected from teachers and school personnel. Importantly, intervention gains may diminish over time as a result of the ongoing developmental challenges that adolescents on the spectrum experience, with long-term sustainability of gains of the multilevel resilience intervention beyond the immediate program effects yet to be determined.

Future Research

The encouraging findings from this proof-of-concept study justify a RCT of the multilevel resilience intervention to explore further the quantitative and qualitative factors that influence school connectedness outcomes to increase understanding about why the program results in an improvement in the mental wellbeing of some adolescents on the autism spectrum, while that of others remains constant or deteriorates. Investigating mediators and moderators of potential program effects may augment this understanding and should be considered. Also, conducting an RCT would allow for many of the afore-mentioned limitations regarding study design to be addressed. As young adolescents on the spectrum are more vulnerable to developing depression and other mental health problems than their neurotypical peers, and incidence rates are high, ongoing research should explore the optimal focus and frequency of prevention and early interventions to promote more positive mental health with these adolescents and their parents. In line with students reporting difficulty remembering the content of the program, dosage effects would be worth exploring. Introducing booster sessions for students and their parents (either face-to-face or online or via SMS), and conducting follow-up sessions beyond 12 months post-implementation, may reduce or prevent depression and should be explored. Further, given the identified risks for children on the spectrum to develop depression in adolescence and early adulthood (Hannon & Taylor, 2013; Mayes et al., 2011), conducting additional, longer term follow-up with participants would help to inform the duration of program effects. Conducting independent clinical interviews with adolescent participants at each time point would strengthen their self-reports of mental health symptomatology, and as students and parents experienced RAP-A-ASD as improving young adolescents’ affect and emotion regulation, the incorporation of an emotion regulation scale would facilitate further exploration of this construct. For parents, future research should continue to offer RAP-P-ASD workshops while trialling the provision of additional material after the conclusion of workshops to reinforce and sustain parents’ sense of connectedness. For parents unable to attend face-to-face RAP-P-ASD workshops, or who require ongoing revision and reinforcement support in addition to the workshops, there is value in developing a hybrid model of RAP-P-ASD that uses communication technology to deliver program content online, augments it with digital resources and telephone and/or online chat support, and can be accessed worldwide by English speaking parents of young adolescents on the autism spectrum. Such a hybrid would extend the reach of RAP-P-ASD to a wider, more ethnically, culturally and racially diverse population, including those living in rural and remote communities, and internationally, and might help to lessen the sense of isolation experienced by many parents of young adolescents with autism. We have developed the Autism Teen Wellbeing website to support school connectedness for parents, teachers and schools in rural, remote, and urban locations (https://autismteenwellbeing.com.au). As e-health research shows the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions delivered through technology (see Andersson et al., 2014), to further support school connectedness for adolescents in rural, remote, and urban locations, the website should be extended to provide support for adolescents. At the school level, finding and incorporating a method of gathering qualitative data from teachers and school personnel that does not make significant demands on their time would further inform feasibility and acceptability of the multilevel resilience intervention.

Conclusions

The strength-focused multilevel resilience intervention was implemented with good validity and acceptability. Furthermore, promising findings from triangulated quantitative and qualitative data from students and their parents showed some evidence for promoting resilience by enhancing protective factors for adolescents with a diagnosis or traits of autism, their parents, and in their schools. It appears that this intervention offers a feasible and sustainable, primary prevention program for promoting mental health in young adolescents on the autism spectrum that may need to involve the promotion of protective factors at the individual, family and school levels with appropriately timed boosters, and be augmented by timely tertiary care support. As depression and other mental health problems have a strong influence on developmental outcomes for adolescents on the spectrum, outcomes justify proceeding with a RCT with more representative samples to explore the optimal focus and dosage of prevention and early interventions to promote more positive mental health in adolescents on the autism spectrum.

Availability of Data and Material

Corresponding author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

The Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (Autism CRC), the world’s first national, cooperative research effort focused on autism, funded this research.

Professional development demands on staff precluded one school from attending a RAP-T-ASD workshop. Fortunately, this school has a well-developed Enrichment Centre and teachers who are very experienced in teaching young adolescents on the autism spectrum.

The lower the alpha value, the greater the reliable change index, making it harder for change to meet the threshold required to be classified as statistically significant.

References