Abstract

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had an adverse impact on the physical and mental health of the public worldwide. In addition to illness in patients with COVID-19, isolated people and the general population have experienced mental health problems due to social distancing policies, mandatory lockdown, and other psychosocial factors, and the prevalence of depression and anxiety significantly increased during the pandemic. The purpose of this review is to elucidate the epidemiology, contributing factors, and pathogenesis of depression and anxiety. during the pandemic. These findings indicate that physicians and psychiatrists should pay more attention to and identify those with a high risk for mental problems, such as females, younger people, unmarried people, and those with a low educational level. In addition, researchers should focus on identifying the neural and neuroimmune mechanisms involved in depression and anxiety, and assess the intestinal microbiome to identify effective biomarkers. We also provide an overview of various intervention methods, including pharmacological treatment, psychological therapy, and physiotherapy, to provide a reference for different populations to guide the development of optimized intervention methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the emergence of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in December 2019, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has infected over 500 million people worldwide (World Health Organization. https://covid19.who.int/). Severe respiratory symptoms, high mortality rates, and rapid transmissibility have made COVID-19 a severe illness that has had a negative impact on both physical and mental health [1, 2]. During the pandemic, many people have experienced severe anxiety and fear of getting sick, which has led to a series of mental health symptoms, including lack of motivation, anhedonia, exhaustion, irritability, and sleep disturbance. Depression and anxiety during COVID-19 have been major causes of a global health-related burden and will have long-term economic and social consequences [2].

Recent literature from the COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators indicates that the prevalence and burden of depression and anxiety has increased significantly during the pandemic [2]. They estimated the addition of 53.2 million new patients with major depressive disorder and 76.2 million cases of new anxiety disorders globally throughout 2020. Meanwhile, they found that daily SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and reduced mobility were associated with increased prevalence of depression and anxiety. As SARS-CoV-2 evolved, variable virus strains caused illness with differences in the severity of pneumonia, treatment approaches, vaccination, and control measures, and subsequent COVID-19-related mental health problems also varied. A new variant with rapid transmissibility, SARS-CoV-2 Omicron, resulted in a new worldwide outbreak, resulting in mental health problems that differed from those prevalent at the beginning of the pandemic [3].

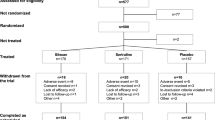

The purpose of this review is to elucidate the epidemiology, contributing factors, and pathogenesis of depression and anxiety during the pandemic and to discuss mechanisms and treatments. Recently, studies focusing on the etiology of COVID-19-related depression and anxiety suggested that changes in brain structure and inflammation may be the underlying mechanisms responsible for depression and anxiety, although the exact mechanism remains unclear. Probing the neural mechanism is imperative for the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19-related depression and anxiety. We also summarize pharmacological treatments, psychological therapy, and physiotherapy to provide guidance for clinicians (Fig. 1).

Depression and anxiety during COVID-19: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. BBB, blood-brain-barrier; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; REAC, radio electric asymmetric conveyer; Tdcs, transcranial direct current stimulation

Epidemiology

Current literature reports the pooled prevalence of depression and anxiety is 45% and 47% respectively, which is higher than during the non-epidemic period [4]. Populations present some level of worry about COVID-19, regardless of infection status, and the level depends on various contributing factors. We have searched recent literature concerning the mental health problems during COVID-19 and found several risk factors. Consistent findings included age, gender, the periods of the pandemic, location, different populations, educational level, profession, marriage, and comorbidities. In this review, we summarized these contributing factors to provide a potential direction for future research on mental health problems.

Age and Gender

Age and gender had a significant effect on the levels of risk for depression and anxiety during the pandemic. Consistent studies have shown that younger people have greater vulnerability to mental diseases [5,6,7]. Zhou et al. reported the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms to be 43.7% and 37.4%, respectively, among Chinese high school students during the COVID-19 outbreak [5]. A longitudinal study indicated that adolescents exhibited more depression and anxiety during the two months following the implementation of government restrictions and online learning [8]. Ahmed et al. investigated these psychological problems during the pandemic among all ages and found that young people aged 21–40 years were more vulnerable in terms of their mental health conditions [6]. The anxiety risk of people older than 40 years was only 0.40 times higher than that of younger people [9]. The frequency of social media exposure (SME) might be responsible for this difference in anxiety risk [7]. In another study, older people (>50 years) were reported to be another group at risk for developing mental problems [10], possibly due to loneliness, lack of physical activity, and ageism [11, 12]. The inconsistency among results may be related to different races and evaluation methods in the different studies.

Gender is another demographic characteristic that has been reported to as a factor associated with mental health problems. A number of studies reported that being female increased vulnerability to depression and anxiety during the pandemic [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Wang et al. conducted a cross-sectional trial among the general population in China that included 600 respondents, and found that the risk of anxiety in females was three times higher than that in males [9]. The vulnerability of females may be due to the higher proportion of SME [7]. Many women worked in healthcare during the pandemic or took care of their families, and the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine policies might have significantly affected their lifestyle and led to greater worries [19]. Especially, pregnant women were more affected [20], with a 37% incidence of depression and 57% incidence of anxiety. Pregnant women tended to fear that COVID-19 would threaten both their life and that of their baby, and they worried about obtaining necessary prenatal care and social isolation [21]. However, limited inconsistent findings suggested that male participants displayed a higher risk for depression and anxiety [22]. Many factors could explain differences between males and females, such as differences in participation in risky behaviors (e.g., going to crowded places or not wearing masks) during the pandemic and differences in the infection rate between males and females. In addition to those social factors, biological underpinnings also played a critical role in women’s susceptibility to depression and anxiety. For example, gonadal hormones contributed to the diathesis factor of emotional dysregulation being over-represented in females [23].

Different Periods of the Pandemic and Different Populations

The prevalence of depression and anxiety have varied throughout the different periods of the pandemic. There was a spike in the number of cases over a short period of time between January 23 and March 10, 2020 in China, which can be called an outbreak. Wang et al. conducted a longitudinal study and found that the rates of depression and anxiety were 16.5% and 28.8% during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 [24]. Their subsequent evaluation showed no significant longitudinal changes in the rates of mental disorders compared to the initial evaluation. However, a large-scale online survey during the outbreak reported higher rates [22]. Another study reported rates of depression and anxiety of 27.9% and 31.6%, respectively, among the survey respondents, markedly higher than pre-pandemic levels [25]. The elevated prevalence may be due to fear of infection and home quarantine [22]. Since March 10, 2020, COVID-19 in China has been basically under control, with newly-confirmed cases in Hubei Province at zero, and newly-confirmed cases nationwide showing a consistent downward trend. This phase was considered to be a period of remission. During the remission period, there was a persistent increase in the level of depression and anxiety among Chinese college students, with a longitudinal survey reporting elevated rates relative to values during the onset of the outbreak (21.6% vs 26.3% for depression, 11.4% vs 14.7% for anxiety) [26]. Less physical exercise and social support were found to be associated with psychological symptoms [26]. Zaninotto et al. reported that mental health began to recover in July through October 2020, but the prevalence of depression and anxiety then increased further by the end of 2020 compared to June 2020 [27]. This trend might be associated with increased loneliness and decreased quality of life during the lockdown phases [14, 27]. These findings suggest that mental health problems during different stages of the pandemic could be attributed to different psychosocial factors, which need to be recognized as early as possible.

Besides, different populations varied in the prevalence of depression and anxiety, and this may be associated with the possibility of epidemic exposure. Mazza and colleagues reported the prevalence rates of depression and anxiety were 31% and 42% in COVID-19 survivors [28]. Furthermore, the prevalence of depression and anxiety was reported to be highest among patients with COVID-19 infection 55%[48%–62%] and 56%[39%–73%] [29]. They had higher levels of depression and anxiety (both P <0.001), compared to non-COVID controls [30]. Notably, non-COVID populations also displayed a significantly increased prevalence of depression and anxiety. A cross-sectional online study during self-quarantine showed that 50.9% of participants had traits of anxiety and 58.6% exhibited depression [31]. Results from multiple countries suggested that the pooled prevalence of depression was 21.7% (95% CI, 18.3%–25.2%), and of anxiety was 22.1% (95% CI, 18.2%–26.3%) in health-care workers [32], which was similar to that in general populations. Hence, it is necessary to pay different levels of attention to the mental health problems of the various populations.

Education, Living Location, Profession, and Marital Status

In addition to demographic features, socioeconomic factors might affect the prevalence of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several studies reported that educational level was associated with the risk of mental disorders. Zhao et al. found that people with low levels of education (senior high school and below) showed more anxiety symptoms than those with higher levels (college and above) [33]. A study in Australia also suggested that a high educational level was protective against depression [34]. Furthermore, a cross-sectional investigation in China showed that the risk of depression for those with a master’s degree was only one-third that of those with a bachelor’s degree [9]. However, a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh found that individuals with a higher educational level (above college) had more anxiety symptoms [35]. Differences in ethnicity and self-rating scales may account for the inconsistent results.

Living location is another factor associated with depression and anxiety during COVID-19. Several studies showed that people living in rural areas had higher levels of anxiety [26, 35]. Rural people had a higher frequency of SME, which was correlated with the prevalence of mental health problems [26]. Lower levels of economic security, material security, and sanitary conditions also contributed to the problem in rural areas [35]. However, urban residents were also at risk of developing depression and anxiety symptoms [11, 36]. The majority of COVID-19 cases are occurring in urban areas [36]. Cities are more densely populated, and therefore more susceptible to novel coronavirus transmission. A study conducted in 204 countries estimated large increases in the prevalence of mental health conditions in Latin America, the Caribbean, North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia [2]. Zheng et al. reported that the proportion of severe depression during the pandemic in Hubei Province was more than double that of other provinces in China during the outbreak [37]. Overall, the mental health problems were associated with the COVID-19 control strategies and social distancing policies in the province. These results indicate that agencies should strengthen supervision over social media news and guarantee the accuracy of reporting on the epidemic situation.

Moreover, recent studies have revealed an association of profession with susceptibility to depression and anxiety during COVID-19, especially in front-line healthcare workers, migrant workers, and workers in contact with the public [36, 38]. Zhang et al. found a higher prevalence of insomnia (38.4% vs 30.5%), anxiety (13.0% vs 8.5%), and depression (12.2% vs 9.5%; P <0.04) in medical health workers compared with non-medical health workers [36]. Another study by Liu and colleagues reported that medical staff who had direct contact treating infected patients experienced higher anxiety scores than those who had no direct contact [38]. For migrant workers, the dominating anxiety was from the suspension of productive activity, loss of income, and fear of the future. For workers in contact with the public, anxiety was a possible consequence of being exposed to infection every day. Notably, populations with a stable family income and living with the family reported fewer mental problems. Therefore, we ought to pay more attention to staff in these special occupations, make psychological measurements, and provide interventions.

The effect of marital status on mental health problems varied across studies. Several studies reported more anxiety, depression, and insomnia in married than in unmarried people [7, 16, 17, 35]. Fu et al. found that married people frequently worry more about their family’s health than about their own health [17]. However, Shi et al. found a higher risk of depression and anxiety in unmarried people [22]. Two studies reported that divorce or widowhood was an important predictor of the levels of depression and anxiety [33, 39], possibly as a consequence of greater loneliness and the lack of emotional support [33, 34]. Discrepancies among studies in terms of pandemic period, location, and measurement tools may account for the inconsistency of results.

Comorbidity

Comorbidity of chronic diseases has been another risk factor for mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic [24, 34, 36, 40]. A multinational and multicenter study conducted by Chew et al. reported that healthcare workers with comorbid chronic diseases, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, had greater susceptibility to psychological problems than those without comorbidities [41]. Lotzin et al. found that comorbidity of psychiatric diseases increased people’s vulnerability to depressive and anxiety symptoms during the pandemic [42]. The increased difficulty in accessing medical care during the pandemic is an important reason for the increase in depression and anxiety associated with chronic illness [42, 43]. For people with comorbid chronic diseases who are susceptible to mental health problems, regular psychological assessments should be conducted at the same time as the underlying diseases are being treated.

Mechanism

Considering the high prevalence of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have focused on identifying the mechanism responsible for these illnesses and on better understanding, recognition, and treatment. As a non-invasive technology, functional magnetic resonance imaging has been applied to explore the neural mechanism that underlies depression and anxiety. Pre-pandemic brain function, structure, and connectome have been reported to be predictive factors for depression and anxiety during the pandemic. Recent studies also showed the imperative roles of the direct and indirect immune response on the neuroimmune substrates involved in depression and anxiety during COVID-19. In addition, several studies reported an association between intestinal microbiota and mood disorders.

Neural Mechanism

Recently, researchers have probed the neural mechanisms involved in depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. The major findings focused on brain structural morphology, functional activity, and neural networks. Abnormal structure in the limbic region has been reported in patients with depression and anxiety. Holt-Gosselin et al. found that reduced thickness in the insula before the pandemic predicted more severe anxious arousal symptoms during COVID-19. Anhedonia, as predicted by self-distraction, interacts with amygdala volume [44]. In a longitudinal investigation, Salomon et al. found increased volume in the bilateral amygdala, putamen, and anterior temporal cortices following the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown, but the volumes decreased as time elapsed after lockdown [45]. This finding suggests that the intense experience associated with the pandemic induced transient volumetric changes in brain regions commonly associated with stress and anxiety. In another study, Jamieson et al. found that structural integrity of the posterior limb of the internal capsule pre-pandemic was associated with worry and rumination during COVID-19 [46]. These results suggest that early brain structural changes were predisposed to trigger anxiety or depressive symptoms during the onset of COVID-19.

Based on a functional neuroimaging study, Khorrami et al. suggested that greater anterior insular activation in response to unpredictable threat and greater self-reported intolerance of uncertainty are independent predictors of increased pandemic-related negative affect [47]. Du et al. reported that altered amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation in regions related to emotion and sleep regulation occurred in COVID-19 survivors [48], and Zhang et al. reported that decreased functional connectivity of amygdala subregions predicted vulnerability to depression following the pandemic [49]. A long-term longitudinal study using 18F-FDG-PET/CT reported lasting prefrontal, insular, and subcortical metabolism in COVID-19 patients with anxio-depressive symptoms [50]. However, functional neuroimaging investigations conducted during COVID-19 are limited, and most studies were retrospective. Future observational and prospective investigations are needed.

The functional connectome is another potential mechanism that might underlie pandemic-related depression and anxiety disorders. He et al. reported that the pre-pandemic functional connectome could predict pandemic-related anxiety [51]. They proposed that weaker connectivity between the executive control network and the salience network might account for increased signs of pandemic-related anxiety. Those with lower top-down executive control [52] failed to inhibit or regulate somatic and autonomic bodily states [53, 54] and the hyperactivity caused by detecting and filtering salient stressful events [55]. He et al. also found that another neural circuit involving the insula, thalamus, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus and the sensorimotor cortex was associated with higher pandemic-related anxiety. This evidence emphasizes that the pandemic-related anxiety may result from distributed neural circuits.

Neuroimmune Mechanism

Current literature suggests that the interaction between neurocircuits and neuroinflammation drives the development of depression. Therefore, the neuroimmune response may have played a critical role in depression during the pandemic. Ellul et al. reported that direct infection of the central nervous system can induce psychological symptoms due to the potential neurotropism of coronaviruses [56]. Dantzer et al. reported that neuroinflammation, blood-brain-barrier disruption, peripheral immune cell invasion into the central nervous system, neurotransmission impairment, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, microglial activation, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase induction were involved in the neuroimmune mechanism of depression and anxiety development during the pandemic [57,58,59,60].

In addition to direct viral infection, an indirect immune response to viral infection may have played an equivalent role in the development of mental symptoms during the pandemic. For example, Pedersen reported that the virus can trigger a cytokine storm that induces a series of immune responses [57, 61]. The production of cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators increases both locally and systemically [62]. COVID-19 patients showed elevated levels of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, interferon (IFN)-γ, CXCL10, and CCL2, suggesting activation of T-helper-1 cell function. Several studies indicated that the amount of IL-6 and IL-1β may be related to the risk of developing post-COVID depression. Moreover, patients with COVID-19 displayed higher levels of T-helper-2 cell-secreted cytokines (such as IL-4 and IL-10) [63, 64]. Higher concentrations of these cytokines may predict a worse clinical course [65]. Notably, the dysregulation of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and transforming growth factor-β is associated with psychiatric diseases [66,67,68,69,70]. Nevertheless, the evidence described above came mostly from cross-sectional investigations, and longitudinal changes need to be evaluated. In the future, cohort studies are needed to determine the changes in neuroimmune factors related to post-COVID depression and anxiety symptoms in order to identify biomarkers.

Intestinal Microbiological Mechanism

The association between intestinal microbiota and mood disorders is currently a hot research topic. Numerous studies have shown that depression and anxiety are associated with an imbalance of intestinal flora, which leads to abnormality in the gut-brain axis [71, 72]. Ghannoum et al. reported that altered intestinal flora in the multiple dimensions of the gut-brain axis had a negative impact, including excessive activation of the HPA axis (cortisol), neural circuits, and the level of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, as well as excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the immune system (e.g., IL-6) and the destruction of the intestinal barrier [71]. Eventually these changes contributed to depression and anxiety. Nakov et al. reported an increased prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown [73]. They found that the occurrence of these symptoms was associated with dysfunction of the gut-brain axis, thereby causing changes in the neuroimmune and endocrine systems and promoting the development of depression and anxiety. In an animal study, Tian et al. showed that Lactococcus CCFM6432 effectively reduced stress-induced anxiety behavior by alleviating overactivation of the HPA axis and improving the composition of intestinal flora [74]. These studies indicate that COVID-19 infection can cause depression and anxiety symptoms by changing the intestinal microbiome. These findings provide direction for developing interventions to treat COVID-19-related depression and anxiety.

Treatment

Depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic have had a profound impact on people's lives, and in response, researchers placed a high priority on interventions. Pharmacological therapy, such as antidepressant and antianxiety drugs, play a critical role in the intervention for depression and anxiety. In addition, psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based interventions, progressive muscle relaxation training, and internet-based interventions played an important role in alleviating psychological problems during COVID-19 [75,76,77,78]. Another effective treatment was physical therapy, as neuromodulation and exercise have been shown to alleviate depressive and anxiety symptoms [79].

Pharmacological Therapy

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are the most commonly used antidepressants, but to date no longitudinal clinical efficacy studies of their use during the pandemic have been published. Although ketamine is rarely used clinically, Rosenblat et al. reported that it could relieve depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and anxiety symptoms in patients with depression both pre- and post-pandemic [80].

Anxiety disorders are usually treated with antidepressants and benzodiazepines, and these were the main drugs used to treat anxiety during COVID-19. During the pandemic, it was particularly crucial to control acute anxiety attacks in patients infected with COVID-19. Khawam et al. found that administering alprazolam reduced the risk of respiratory depression and acute respiratory failure in COVID-19 patients with acute anxiety [81]. Besides, olanzapine, quetiapine, or haloperidol were effective in treating anxiety disorder [81]. Based on traditional Chinese medicine theory, Ma et al. found that Suanzaoren Decoction, Huanglian Ejiao Decoction, and Zhizi Chi Decoction reduced anxiety symptoms [82].

Although the use of classic antidepressant and antianxiety drugs during the pandemic were less reported, empirical treatment has evidenced their confirmed efficacy in depression and anxiety. For the newer drugs, we need more information that is based on the actual situation of patients and the monitoring of adverse effects.

Psychological Interventions

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed tremendous mental health stress on people [83]. Psychological interventions are often regarded as the fundamental treatment for mental disorders, and several studies focused on such interventions during COVID-19, including CBT, mindfulness-based interventions, behavioral interventions, and internet-based interventions.

Recent studies have shown that CBT was effective at relieving depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with COVID-19 [75, 84, 85]. Li et al. found a positive effect of face-to-face CBT on improving the mental health of patients with COVID-19 [75]. Liu et al. reported that computerized CBT and face-to-face interventions had similar efficacy [84]. Due to lower net societal costs and reduced risk of exposure [86], internet-delivered CBT can be a superior psychological therapy during the pandemic.

Several investigations have reported the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on mental health problems [76, 87,88,89,90]. Maria Antònia et al. reported that the PsyCovidApp group showed significant improvements in insomnia, anxiety, and stress [87]. Malboeuf-Hurtubise reported that mindfulness-based intervention enhanced the basic psychological need satisfaction for elementary school students [90].

As a behavioral intervention, progressive muscle relaxation training was shown to improve sleep quality and reduce depression and anxiety in patients with COVID-19 [77, 91]. Similarly, depressive and anxiety symptoms were significantly reduced via 10-day psychological support and breathing exercises [92]. Therefore, we recommend that this behavioral intervention be introduced to the general hospital setting during the pandemic.

Current evidence suggests that internet-based integrated intervention can decrease the levels of anxiety, depression, and perceived stress and increase resilience [78, 93]. In addition, worry, anhedonia, COVID-19-related fears, and contamination fears could be also alleviated [94]. Thus, internet-based interventions may offer a viable and scalable means of mitigating the rising mental health problems during the pandemic.

Physiotherapy

In addition to pharmacological and psychological treatment, physiotherapy is an alternative or complementary therapy [79]. Prior evidence has confirmed the efficacy of neuromodulation on depression, and the positive effect and minimal adverse effects make it acceptable for patients with mental health problems [79, 95]. In addition, as part of a healthy lifestyle, exercise has been reported to be a fundamental intervention for depression and anxiety.

In one study, researchers applied two radio electric asymmetric conveyer (REAC) technology neuromodulation treatments to reduce psychosocial unease. They found that the REAC treatment helped patients with COVID-19 utilize better coping strategies to deal with environmental stress and relieve depressive and anxiety symptoms [96]. Shinjo et al. reported that bifrontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) significantly reduced the severe anxiety of a patient with COVID-19 [97]. Although no random-blind controlled trials conducted during the pandemic have been reported, expert consensus considers tDCS to be a potential treatment for mental distress associated with the COVID-19 epidemic [97, 98].

A large body of evidence has suggested that regular exercise significantly reduces the risk of depression and anxiety, and it is considered to be beneficial in the prevention of about 25 conditions [99,100,101,102]. To avoid spreading the virus, a balance of outdoor and indoor physical exercise should be maintained. Nagarathna et al. reported that yoga practice is a beneficial indoor exercise that reduced stress and anxiety and enhances immunity [103].

Based on these reports, different interventions can be selected according to different periods of the pandemic. For example, tDCS or REAC can be used to treat hospitalized COVID-19 patients. For close contacts living together, yoga practice or other indoor exercise can be performed during the period of isolation. Compared to exercising indoors, exercising outdoors brings about greater feelings of revitalization and positive engagement, as well as a decrease in depression and anxiety [104]. Therefore, for the general population, outdoor exercise is recommended.

Conclusions

In this review, we described several factors contributing to depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. For those populations at high risk of developing mental problems, psychological examinations should be conducted and more family and social support provided. Pathogenesis studies focused on neuroimaging, neuroimmune, and intestinal microbiology have identified potential biomarkers for the identification and diagnosis of mental disorders during the pandemic. Furthermore, new intervention targets for specific aberrant brain functions and immunity are promising. Drugs, psychological therapy, and physiotherapy are the three most commonly-used options for the treatment of mental disorders. However, due to the particulars of quarantine policies, treatment plans must be adjusted and optimized to a given situation. For patients with severe depression and anxiety, antidepressants ad antianxiety drugs should be prescribed. The options are more diverse for patients with moderate or mild mental health problems, such as tDCS or REAC for hospitalized COVID-19 patients, yoga or other indoor exercise for quarantined people, and outdoor exercise for the general populations. Overall, this review provides a reference for the identification, diagnosis, and optimized treatment of patients with depression and anxiety, with the goal of minimizing the adverse impact of COVID-19 on human well-being.

References

Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res 2020, 24: 91–98.

Collaborators C1MD. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398: 1700–1712.

Araf Y, Akter F, Tang YD, Fatemi R, Parvez MSA, Zheng C. Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: Genomics, transmissibility, and responses to current COVID-19 vaccines. J Med Virol 2022, 94: 1825–1832.

Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, Silver Z, Wong CY, Chang O, et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2021, 1486: 90–111.

Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, Guo ZC, Wang JQ, Chen JC, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020, 29: 749–758.

Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Zhou A, Sang H, Liu S, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatry 2020, 51: 102092.

Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One 2020, 15: e0231924.

Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolescence 2021, 50: 44–57.

Wang Y, Di Y, Ye J, Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol Health Med 2021, 26: 13–22.

Tian F, Li H, Tian S, Yang J, Shao J, Tian C. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res 2020, 288: 112992.

Creese B, Khan Z, Henley W, O'Dwyer S, Corbett A, Vasconcelos Da Silva M, et al. Loneliness, physical activity, and mental health during COVID-19: A longitudinal analysis of depression and anxiety in adults over the age of 50 between 2015 and 2020. Int Psychogeriatr 2021, 33: 505–514.

Bergman YS, Cohen-Fridel S, Shrira A, Bodner E, Palgi Y. COVID-19 health worries and anxiety symptoms among older adults: The moderating role of ageism. Int Psychogeriatr 2020, 32: 1371–1375.

Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, Colasanti M, Ferracuti S, Napoli C, et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17: 3165.

Pedersen MT, Andersen TO, Clotworthy A, Jensen AK, Strandberg-Larsen K, Rod NH, et al. Time trends in mental health indicators during the initial 16 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22: 25.

Sønderskov KM, Dinesen PT, Santini ZI, Østergaard SD. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2020, 32: 226–228.

Banna MHA, Sayeed A, Kundu S, Christopher E, Hasan MT, Begum MR, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the adult population in Bangladesh: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Health Res 2022, 32: 850–861.

Fu W, Wang C, Zou L, Guo Y, Lu Z, Yan S, et al. Psychological health, sleep quality, and coping styles to stress facing the COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10: 225.

Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397: 220–232.

Wenham C, Smith J, Morgan R, Group GAC1W. COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395: 846–848.

Berthelot N, Lemieux R, Garon-Bissonnette J, Drouin-Maziade C, Martel É, Maziade M. Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020, 99: 848–855.

Lebel C, MacKinnon A, Bagshawe M, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Giesbrecht G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 2020, 277: 5–13.

Shi L, Lu ZA, Que JY, Huang XL, Liu L, Ran MS, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3: e2014053.

Parker G, Brotchie H. Gender differences in depression. Int Rev Psychiatry 2010, 22: 429–436.

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 87: 40–48.

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392: 1789–1858.

Li Y, Zhao J, Ma Z, McReynolds LS, Lin D, Chen Z, et al. Mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A 2-wave longitudinal survey. J Affect Disord 2021, 281: 597–604.

Zaninotto P, Iob E, Demakakos P, Steptoe A. Immediate and longer-term changes in the mental health and well-being of older adults in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79: 151–159.

Mazza MG, de Lorenzo R, Conte C, Poletti S, Vai B, Bollettini I, et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 89: 594–600.

Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2020, 291: 113190.

Guo Q, Zheng Y, Shi J, Wang J, Li G, Li C, et al. Immediate psychological distress in quarantined patients with COVID-19 and its association with peripheral inflammation: A mixed-method study. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88: 17–27.

Shah SMA, Mohammad D, Qureshi MFH, Abbas MZ, Aleem S. Prevalence, psychological responses and associated correlates of depression, anxiety and stress in a global population, during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Community Ment Health J 2021, 57: 101–110.

Li Y, Scherer N, Felix L, Kuper H. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16: e0246454.

Zhao H, He X, Fan G, Li L, Huang Q, Qiu Q, et al. COVID-19 infection outbreak increases anxiety level of general public in China: Involved mechanisms and influencing factors. J Affect Disord 2020, 276: 446–452.

Newby JM, O’Moore K, Tang S, Christensen H, Faasse K. Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. PLoS One 2020, 15: e0236562.

Islam MS, Ferdous MZ, Potenza MN. Panic and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi people: An online pilot survey early in the outbreak. J Affect Disord 2020, 276: 30–37.

Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom 2020, 89: 242–250.

Zheng X, Guo Y, Ma W, Yang H, Luo L, Wen L, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of college students in Jinan during the peak stage of the COVID-19 epidemic and the society reopening. Biomed Hub 2021, 6: 102–110.

Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, Xu X, Dou QL, Zhang WW, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: A cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect 2020, 148: e98.

Lei L, Huang X, Zhang S, Yang J, Yang L, Xu M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in southwestern China. Med Sci Monit 2020, 26: e924609.

Guo Y, Cheng C, Zeng Y, Li Y, Zhu M, Yang W, et al. Mental health disorders and associated risk factors in quarantined adults during the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 2020, 22: e20328.

Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJH, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88: 559–565.

Lotzin A, Krause L, Acquarini E, Ajdukovic D, Ardino V, Arnberg F, et al. Risk and protective factors, stressors, and symptoms of adjustment disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic - First results of the ESTSS COVID-19 pan-European ADJUST study. Eur J Psychotraumatology 2021, 12: 1964197.

Özdin S, Bayrak Özdin Ş. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020, 66: 504–511.

Holt-Gosselin B, Tozzi L, Ramirez CA, Gotlib IH, Williams LM. Coping strategies, neural structure, and depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study in a naturalistic sample spanning clinical diagnoses and subclinical symptoms. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci 2021, 1: 261–271.

Salomon T, Cohen A, Barazany D, Ben-Zvi G, Botvinik-Nezer R, Gera R, et al. Brain volumetric changes in the general population following the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown. NeuroImage 2021, 239: 118311.

Jamieson D, Kannis-Dymand L, Beaudequin DA, Schwenn P, Shan Z, McLoughlin LT, et al. Can measures of sleep quality or white matter structural integrity predict level of worry or rumination in adolescents facing stressful situations? Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc 2021, 91: 110–118.

Khorrami KJ, Manzler CA, Kreutzer KA, Gorka SM. Neural and self-report measures of sensitivity to uncertainty as predictors of COVID-related negative affect. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 2022, 319: 111414.

Du YY, Zhao W, Zhou XL, Zeng M, Yang DH, Xie XZ, et al. Survivors of COVID-19 exhibit altered amplitudes of low frequency fluctuation in the brain: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study at 1-year follow-up. Neural Regen Res 2022, 17: 1576–1581.

Zhang S, Cui J, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Liu R, Chen X, et al. Functional connectivity of amygdala subregions predicts vulnerability to depression following the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 2022, 297: 421–429.

Kas A, Soret M, Pyatigoskaya N, Habert MO, Hesters A, Le Guennec L, et al. The cerebral network of COVID-19-related encephalopathy: A longitudinal voxel-based 18F-FDG-PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021, 48: 2543–2557.

He L, Wei D, Yang F, Zhang J, Cheng W, Feng J, et al. Functional connectome prediction of anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Psychiatry 2021, 178: 530–540.

Badre D, Nee DE. Frontal cortex and the hierarchical control of behavior. Trends Cogn Sci 2018, 22: 170–188.

McCormick DA, McGinley MJ, Salkoff DB. Brain state dependent activity in the cortex and thalamus. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2015, 31: 133–140.

Rolls ET. Functions of the anterior insula in taste, autonomic, and related functions. Brain Cogn 2016, 110: 4–19.

Uddin LQ. Salience processing and insular cortical function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015, 16: 55–61.

Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, Lant S, Michael BD, Easton A, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19: 767–783.

Dantzer R. Neuroimmune interactions: From the brain to the immune system and vice versa. Physiol Rev 2018, 98: 477–504.

Najjar S, Pearlman DM, Alper K, Najjar A, Devinsky O. Neuroinflammation and psychiatric illness. J Neuroinflammation 2013, 10: 43.

Benedetti F, Aggio V, Pratesi ML, Greco G, Furlan R. Neuroinflammation in bipolar depression. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11: 71.

Jones KA, Thomsen C. The role of the innate immune system in psychiatric disorders. Mol Cell Neurosci 2013, 53: 52–62.

Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, Cassell M, Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol 2008, 82: 7264–7275.

Cameron MJ, Bermejo-Martin JF, Danesh A, Muller MP, Kelvin DJ. Human immunopathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Virus Res 2008, 133: 13–19.

Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘Cytokine storm’ in COVID-19. J Infect 2020, 80: 607–613.

Channappanavar R, Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: Causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol 2017, 39: 529–539.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. Lancet 2020, 395: 497–506.

Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, de Andrade NQ, Liu CS, Fernandes BS, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: A meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017, 135: 373–387.

Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A, Kirkpatrick B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: Clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry 2011, 70: 663–671.

Renna ME, O’Toole MS, Spaeth PE, Lekander M, Mennin DS. The association between anxiety, traumatic stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders and chronic inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 2018, 35: 1081–1094.

Poletti S, Leone G, Hoogenboezem TA, Ghiglino D, Vai B, de Wit H, et al. Markers of neuroinflammation influence measures of cortical thickness in bipolar depression. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 2019, 285: 64–66.

Benedetti F, Poletti S, Hoogenboezem TA, Locatelli C, de Wit H, Wijkhuijs AJM, et al. Higher baseline proinflammatory cytokines mark poor antidepressant response in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2017, 78: e986–e993.

Ghannoum MA, Ford M, Bonomo RA, Gamal A, McCormick TS. A microbiome-driven approach to combating depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Nutr 2021, 8: 672390.

Luo J, Liang S, Jin F. Gut microbiota in antiviral strategy from bats to humans: A missing link in COVID-19. Sci China Life Sci 2021, 64: 942–956.

Nakov R, Dimitrova-Yurukova D, Snegarova V, Nakov V, Fox M, Heinrich H. Increased prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders of gut-brain interaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: An Internet-based survey. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022, 34: e14197.

Tian P, Chen Y, Qian X, Zou R, Zhu H, Zhao J, et al. Pediococcus acidilactici CCFM6432 mitigates chronic stress-induced anxiety and gut microbial abnormalities. Food Funct 2021, 12: 11241–11249.

Li J, Li X, Jiang J, Xu X, Wu J, Xu Y, et al. The effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on depression, anxiety, and stress in patients with COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11: 580827.

Smith RB, Mahnert ND, Foote J, Saunders KT, Mourad J, Huberty J. Mindfulness effects in obstetric and gynecology patients during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2021, 137: 1032–1040.

Liu K, Chen Y, Wu D, Lin R, Wang Z, Pan L. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety and sleep quality in patients with COVID-19. Complementary Ther Clin Pract 2020, 39: 101132.

Shaygan M, Yazdani Z, Valibeygi A. The effect of online multimedia psychoeducational interventions on the resilience and perceived stress of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A pilot cluster randomized parallel-controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21: 93.

Baptista AF, Baltar A, Okano AH, Moreira A, Campos ACP, Fernandes AM, et al. Applications of non-invasive neuromodulation for the management of disorders related to COVID-19. Front Neurol 2020, 11: 573718.

Rosenblat JD, Lipsitz O, di Vincenzo JD, Rodrigues NB, Kratiuk K, Subramaniapillai M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of repeated ketamine infusions for treatment resistant depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 2021, 303: 114086.

Khawam E, Khouli H, Pozuelo L. Treating acute anxiety in patients with COVID-19. Cleve Clin J Med 2020: 2020May14.

Ma K, Wang X, Feng S, Xia X, Zhang H, Rahaman A, et al. From the perspective of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Treatment of mental disorders in COVID-19 survivors. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 132: 110810.

Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 89: 531–542.

Liu Z, Qiao D, Xu Y, Zhao W, Yang Y, Wen D, et al. The efficacy of computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with COVID-19: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23: e26883.

Perri RL, Castelli P, La Rosa C, Zucchi T, Onofri A. COVID-19, isolation, quarantine: On the efficacy of Internet-based eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for ongoing trauma. Brain Sci 2021, 11: 579.

Axelsson E, Andersson E, Ljótsson B, Björkander D, Hedman-Lagerlöf M, Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Effect of Internet vs face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for health anxiety: A randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77: 915–924.

Fiol-DeRoque MA, Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Jiménez R, Zamanillo-Campos R, Yáñez-Juan AM, Bennasar-Veny M, et al. A mobile phone-based intervention to reduce mental health problems in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (PsyCovidApp): Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9: e27039.

Matiz A, Fabbro F, Paschetto A, Cantone D, Paolone AR, Crescentini C. Positive impact of mindfulness meditation on mental health of female teachers during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17: 6450.

Accoto A, Chiarella SG, Raffone A, Montano A, de Marco A, Mainiero F, et al. Beneficial effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction training on the well-being of a female sample during the first total lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18: 5512.

Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, Léger-Goodes T, Mageau GA, Joussemet M, Herba C, Chadi N, et al. Philosophy for children and mindfulness during COVID-19: Results from a randomized cluster trial and impact on mental health in elementary school students. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2021, 107: 110260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110260.

Xiao CX, Lin YJ, Lin RQ, Liu AN, Zhong GQ, Lan CF. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation training on negative emotions and sleep quality in COVID-19 patients. Medicine 2020, 99: e23185.

Kong X, Kong F, Zheng K, Tang M, Chen Y, Zhou J, et al. Effect of psychological-behavioral intervention on the depression and anxiety of COVID-19 patients. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11: 586355.

Wei N, Huang BC, Lu SJ, Hu JB, Zhou XY, Hu CC, et al. Efficacy of Internet-based integrated intervention on depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with COVID-19. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2020, 21: 400–404.

Bryant RA, Dawson KS, Keyan D, Azevedo S, Yadav S, Tran J, et al. Effectiveness of a videoconferencing-delivered psychological intervention for mental health problems during COVID-19: A proof-of-concept randomized clinical trial. Psychother Psychosom 2022, 91: 63–72.

Li H, Cui L, Li J, Liu Y, Chen Y. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of neuromodulation procedures in the treatment of treatment-resistant depression: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord 2021, 287: 115–124.

Pinheiro Barcessat AR, Nolli Bittencourt M, Duarte Ferreira L, de Souza Neri E, Coelho Pereira JA, Bechelli F, et al. REAC cervicobrachial neuromodulation treatment of depression, anxiety, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2020, 13: 929–937.

Shinjo SK, Brunoni AR, Okano AH, Tanaka C, Baptista AF. Transcranial direct current stimulation relieves the severe anxiety of a patient with COVID-19. Brain Stimul 2020, 13: 1352–1353.

Cappon D, den Boer T, Jordan C, Yu W, Lo A, LaGanke N, et al. Safety and feasibility of tele-supervised home-based transcranial direct current stimulation for major depressive disorder. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 13: 765370.

Rhodes RE, Warburton DER, Murray H. Characteristics of physical activity guidelines and their effect on adherence: A review of randomized trials. Sports Med 2009, 39: 355–375.

Alford L. What men should know about the impact of physical activity on their health. Int J Clin Pract 2010, 64: 1731–1734.

Wu C, Yang L, Tucker D, Dong Y, Zhu L, Duan R, et al. Beneficial effects of exercise pretreatment in a sporadic Alzheimer’s rat model. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2018, 50: 945–956.

Wu C, Yang L, Li Y, Dong Y, Yang B, Tucker LD, et al. Effects of exercise training on anxious-depressive-like behavior in alzheimer rat. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2020, 52: 1456–1469.

Nagarathna R, Anand A, Rain M, Srivastava V, Sivapuram MS, Kulkarni R, et al. Yoga practice is beneficial for maintaining healthy lifestyle and endurance under restrictions and stress imposed by lockdown during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12: 613762.

Thompson Coon J, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45: 1761–1772.

Acknowledgements

This review was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82090034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, C., Zhang, T., Li, Q. et al. Depression and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Epidemiology, Mechanism, and Treatment. Neurosci. Bull. 39, 675–684 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-022-00970-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-022-00970-2