Abstract

Gillichthys mirabilis population static measurements (abundance, age, and size class structures) and vital rates (growth, mortality, recruitment) were monitored on an annual basis from 2002 to 2007. Population-level metrics were used to gauge habitat quality at two study sites (a contaminated site and a reference site) in two large northern California estuaries (San Francisco and Tomales Bays). San Francisco Bay populations exhibited slower growth and higher mortality rates and contained higher amounts of contaminants than Tomales Bay. Recruitment rates were highest at contaminated sites (Stege Marsh and Walker Creek) in 3 years out of 5 years, suggesting low adult survival. This study suggests that population-level effects on a residential fish may be attributed to estuarine contamination on the US Pacific coast.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Natural resource management strategies have shifted focus from species specific to ecosystem-based as habitat function has become of global importance. In many locations, estuaries impacted by anthropogenic activities are becoming the focus of large- and small-scale restoration efforts. Estuaries contain vital foraging and reproduction habitats for many marine and euryhaline fishes (Forrester et al. 2003; Mathieson et al. 2000; Methven et al. 2001; Lobry et al. 2003). Along the fringes of temperate estuaries, intertidal salt marshes provide habitat for smaller resident estuarine fishes (McIvor and Odum 1988; Talley 2000; West and Zedler 2000) and nursery areas for larger seasonal users (Kneib 1997; Mathieson et al. 2000). At the interface between land and sea, estuaries concentrate contaminants received from entire watersheds. Pollution from both point and nonpoint sources accumulates in soft estuarine sediments (San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) 1997; Forrester et al. 2003; Hwang et al. 2006a, b, 2009). Tidal marshes become pollution sinks via tidal deposition of contaminated sediments. In 1997, the SFEI found that organic contaminants in intertidal salt marsh sediments were as much as 30 times higher than at monitoring stations in adjacent open water (SFEI 1997).

In order to evaluate the impacts of pollution on estuarine ecosystems, a suite of biological indicators have been implemented to determine lethal and sublethal effects of contaminants and water quality on fishes in temperate estuaries around the world (Goksoyr et al. 1996; Araujo and Williams 2000; Le Pape et al. 2003; Anderson et al. 2006). In San Francisco Bay (SFB), a variety of approaches were used over the last several decades, including assessments of chemical accumulation in tissues and reproductive organs (Spies and Rice 1988) and histopathological analyses. These approaches clearly documented chemical toxicity to individuals in the field and laboratory. Species assemblage monitoring of fishes and invertebrates has also been used as an indicator of estuarine ecosystem quality in SFB (Thompson and Nichols 1984; Meng et al. 1994; Orsi 1999; Thompson and Lowe 2004). This type of monitoring provided information on species distribution and relative abundance in a system and in some cases revealed species sensitive to poor habitat quality (Meng et al. 1994).

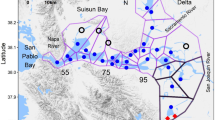

The longjaw mudsucker (Gillichthys mirabilis, Teleostei: Gobiidae) is a resident estuarine fish ranging from Baja California, Mexico, to Humboldt Bay, CA, USA, and has been documented to be one of the most abundant fishes in southern California intertidal salt marsh habitat (Desmond et al. 2000; Talley 2000; West and Zedler 2000). G. mirabilis is a benthic consumer exhibiting high site fidelity that completes its life cycle in a single estuary (Weisel 1947; Yoklavich et al. 1992). This life history strategy makes it an excellent candidate as a bioindicator of ecosystem quality, particularly regarding contaminant bioaccumulation. The Pacific Estuarine Ecosystem Indicator Research (PEEIR) project implemented bioindicator studies using G. mirabilis as a study organism to assess individual response to organic and inorganic contaminants in two northern California estuaries. Fishes at four salt marsh study sites with varying contaminant levels in SFB and Tomales Bay (TB; Fig. 1, Rose et al. 2005; Anderson et al. 2006; Bano et al. 2007) were examined for immune response to contaminant exposure. Individuals from more contaminated habitats exhibited poor liver quality and high levels of apoptosis (programmed cell death, Anderson et al. 2006). Caged field experiments in southern California revealed that individuals contained in marshes with higher contamination had negative growth rates and condition factors (weight loss, Forrester et al. 2003). While evidence suggests that G. mirabilis can be used to detect sublethal contaminant effects at the individual level, no previous work has sought to determine potential population-level effects.

The objective of this study was to apply G. mirabilis population static measurements (abundance, age and size class structures, length frequency) and vital rates (recruitment, growth, mortality) as bioindicators of habitat quality.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

Research occurred in two large northern California estuaries approximately 105 km apart: SFB and TB (Fig. 1). SFB, a highly urbanized estuary with approximately seven million residents, drains about 40% of California’s freshwater (Bennett and Moyle 1996). Major anthropogenic impacts to SFB began over a century ago with hydraulic gold mining, which washed down tons of mercury-laden fine sediments (Hornberger et al. 1999). Two major tributaries to SFB, the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, support a multibillion dollar agricultural industry and have carried a complex mix of pesticides to SFB for decades. Hundreds of kilometers of highway surround SFB; urban stormwater runoff contributes heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) directly into the estuary. The Water Board 303(d) list designates waters of SFB to be impaired by contaminants including pesticides (chlordane, dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethanes (DDT)), heavy metals (mercury, selenium), and industrial waste (polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs); San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board 1999). TB is a rural estuary with a scant 3,000 residents, home to more grazing dairy cows than people. Two sites were chosen within each estuary: a contaminated marsh (Stege Marsh [SFB-SM] in SFB and Walker Marsh [TB-WM] in TB) and a reference marsh (China Camp [SFB-CC] in SFB and Tom’s Point [TB-TP] in TB, Fig. 1).

SFB-SM (27.9 ha) is the most urbanized and contaminated study marsh located in Central San Francisco Bay, approximately 6 km northwest of Berkeley, CA, USA (population 100,700). SFB-SM is in close proximity to an abandoned chemical plant (now referred to as the Cherokee-Simeon Venture property) that operated for over a century (Bowe 2005). Chemical plant operations released over 160 hazardous chemicals directly into SFB-SM including pesticides (chlordane, DDT, dieldrin), toxic metals (copper, lead, selenium, zinc), and industrial waste (PCBs and radioactive materials, San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board 1999; Bowe 2005; Hwang et al. 2006a, b). Consequently, the Water Board designated SFB-SM as a toxic hot spot (San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board 1999). SFB-CC (214 ha) is the reference SFB site located within China Camp State Park (a historic Chinese fishing village), San Pablo Bay, 6 km east of San Rafael, CA, USA (population 56,000). SFB-CC was modified by local mosquito abatement districts until the 1970s; marsh channel networks were modified to be more angular and less meandering (Balling et al. 1980). Remnants of channel modifications persist, with distinct grid-like channel patterns throughout the marsh.

TB-TP (9.3 ha) is the reference TB site located on the northeastern shore of TB approximately 5 km southwest of Tomales, CA, USA (population 200). TB-WM (42 ha) is the contaminated TB site located 2 km southeast of TB-TP. Walker Creek, a 21-km tributary to Tomales Bay, provides freshwater input to TB-WM. Remnants of the historic Gambonini open-pit mercury mining site exist near the headwaters of Walker Creek. Hundreds to thousands of kilograms of mercury have been discharged from the mine into TB since 1972 when mining activities ceased (EPA 1999). This has resulted in fish mercury concentrations leading to consumption guidelines (http://oehha.ca.gov/fish/so_cal/tomales.html).

Contaminants

Surface (0–5 cm) sediment samples were collected using a specially designed Teflon piston pipe (length 2 m, internal diameter 2 cm) in June 2003 and analyzed for inorganic and organic contaminants. To collect surface sediment samples, the Teflon piston pipe was pressed into the surface sediment and pushed to release collected sediment into precombusted glass jars. Samples were taken from 13 stations at SFB-SM, three stations at SFB-CC, three stations at TB-TP, and three stations at TB-WM and analyzed for trace metals and organic contaminants (Hwang et al. 2006a, b). Sediment metal concentrations were determined using the method of Higashi et al. (2005). Analyzed metals included aluminum (Al), arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), lead (Pb), lithium (Li), nickel (Ni), silver (Ag), vanadium (V), and zinc (Zn; see Hwang et al. 2006b for specific methods). Due to budget constraints, neither sediment mercury (Hg) nor methyl mercury (MeHg) were investigated. Organic contaminants analyzed included PAHs, PCBs, DDTs, chlordanes, and phthalates (see Hwang et al. 2006a for specific methods). Toxicity potential of contaminants found in each station was defined by two sediment quality guidelines: low-end guideline (threshold effects level: TEL) and high-end guideline (probable effects level: PEL). Marshes were ranked in order of the toxicity potential (Hwang et al. 2008; Table 1).

A field outplant experiment was conducted at SFB-SM in August 2004 to determine bioavailability of organic and metal contaminants to G. mirabilis. Individuals were caught in a low-contaminant-level southern California site with high G. mirabilis abundance (Carpinteria Marsh, Santa Barbara County, CA, USA; Hwang et al. 2008) and transported live to SFB-SM. Individuals were placed in plastic mesh cages for a period of 60 days. As a benthic consumer, G. mirabilis actively filters sediment while foraging and is thus exposed to contaminants contained in soft bottom sediments. After the experimental period, individuals were sacrificed and analyzed for tissue residues of trace metals and organic contaminants (Hwang et al. 2008).

Static Measurements and Vital Rates

Baited minnow traps were placed in first-order marsh channels at three stations at each study site to determine the relative abundance of G. mirabilis. Sampling occurred on an annual basis during the months of July–August during peak nocturnal high tides. Catch per unit effort (CPUE) was determined for a 24-h period at each station by dividing the number of individuals caught by the total number of traps. An Annual Abundance Index (AAI) was calculated for each marsh as the sum of station CPUEs. Abundance was compared by marsh and year using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). In 2005, only TB sites were sampled; thus, 2005 abundance data were not included in the ANOVA analysis.

A total of 264 individuals taken from all study sites in August 2002–2004 and 2007 were aged by examining annual (if present) or daily growth rings in sagittal otoliths. Individually extracted sagittal otoliths were cleaned of tissue and mounted in resin blocks (Beuhler; Lake Bluff, IL, USA). Transverse cross sections were cut with a low-speed isomet saw (Beuhler; Lake Bluff, IL, USA) and adhered to glass microscope slides with thermoplastic resin (Crystalbond; Aremco Products; Ossining, NY, USA). Otoliths were polished on one side with a 0.3-μm lapping film to expose a transverse plane. Digital images were captured with a digital camera (Pixelink A662; Pixelink; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) coupled with a confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i; El Segundo, CA, USA). Age was estimated either from the total number of annual or daily rings. Each otolith was aged at least twice. Otoliths were aged a third time if readings had greater than a 10% relative standard deviation. If the error was not resolved by a third reading, the sample was removed from the dataset.

Expected age at length and growth rates were estimated using a random-effects approach to fit the von Bertalanffy growth function (VBGF) that incorporates the error associated with multiple age readings per individual (Cope and Punt 2007). It was assumed that fishing mortality was negligible for this species. Thus, estimates of total mortality were equivalent to natural mortality (Cope and Punt 2007).

To determine size class structures of G. mirabilis, length frequency histograms were constructed from each study site and sampling period. Mean length was determined for each study site and sampling period. Due to size overlap in age classes, size class frequency data were divided into two cohorts: young of the year (YOY, <112 mm SL) and adults (>112 mm SL, Table 3).

Recruitment was determined by calculating the percentage of YOY out of the total sample population for each study site and sampling period.

Results

Contaminants

SFB-SM was the most contaminated site, with several contaminants exceeding the PELs including PCBs, DDTs, chlordanes, copper, lead, and zinc (Table 1). All stations at SFB-SM contained contaminants exceeding PEL and TEL, with ten contaminants above TEL and six contaminants over PEL (see Hwang et al. 2008). The 60-day G. mirabilis outplant experiment revealed that several organic contaminants in sediments were bioavailable (see Hwang et al. 2008, Table 2). Body burdens of PCBs, DDTs, and chlordanes increased significantly (from 10 ppb to between 129 and 476 ppb, from <2 ppb to between 67 and 163 ppb, and from <2 to between 11 and 24 ppb, respectively, Table 2) in outplanted fish tissue.

No other study sites contained contaminants above PEL. At SFB-CC, two out of three stations contained contaminants above TEL. In TB, only one station out of both study sites (TB-WM) contained contaminants above TEL (Hwang et al. 2008). Metal total probable effects level quotient (tPELQ) at SFB-CC and TB-WM (2.29 and 1.19, respectively) were at higher levels than TB-TP (Table 1). Contaminant levels in the surface sediments remain relatively constant over a decade (Hornberger et al. 1999; Hwang et al. 2009) because toxic chemical input has been leveled and bioturbation mixes the surface sediments, so analyzed levels applied to the entire study period.

Static Measurements and Vital Rates

Comparing year and site interactions of G. mirabilis abundance (AAI) revealed significant differences (p = 0.031, Fig. 2). Abundance was higher in TB than in SFB in all years except 2007. In some years, abundance was higher at contaminated sites. SFB-SM had higher abundance than SFB-CC in both 2003 and 2004. TB-WM had higher abundance than TB-TP in 2002. Over the entire sampling period, abundance was highest at TB-TP in 2006 (AAI = 8.75) and lowest at SFB-SM in 2006 (AAI = 0; Figs. 3 and 4).

Maximum age for G. mirabilis was determined to be 6 years. SFB-CC did not contain any fish over the age of 2, and thus a VBGF growth curve was constructed for each estuary rather than individual marshes (Fig. 7). SFB-CC exhibited low age variation compared with SFB-SM; thus, maximum length (L ∞ ) showed greater variation (higher SD) in SFB than TB. Growth rate was faster and mortality was lower in TB than SFB (Table 3). The VBGF generated expected size at age (Table 3) consistent with previous estimates of age class distribution in the Salton Sea (YOY = 60–80 mm; age 1 = 80–120 mm; age 2 = 135–140 mm, Walker 1961). SFB-SM age classes had the smallest YOY and age 1 size classes; TB-WM and TB-TP had the largest (Fig. 5). Adult cohorts were more prevalent in TB-WM, TB-TP, and SFB-CC in 2002 and 2003. With the exception of TB-WM in 2005, these three study marshes were dominated by the YOY cohort. In SFB-SM, YOY dominated in 2003 and 2007. In 2006, no fish were caught in SFB-SM.

Recruitment (percentage of YOY) was lower in TB compared to SFB in 3 years out of 5 years (Fig. 6). A general recruitment pattern was observed at all study marshes: lowest in 2002 and highest in 2006 (except SFB-SM, where recruitment was not observed).

Discussion

In this study, G. mirabilis static measurements and vital rates were correlated with elevated concentrations of metals and organic contaminants in SFB study marshes.

Contaminants

When the concentration of a certain chemical in the sediment is lower than the TEL or higher than the PEL, adverse biological effects are observed rarely or frequently, respectively. Even though metal tPELQs were higher at SFB-CC and TB-WM than TB-TP, these were not likely to be considered to contribute to toxicity because they still remained below PELs (Hwang et al. 2008). Thus, toxic effects to benthic-dwelling organisms in TB are likely rare. However, organic contaminants were readily bioavailable as evidenced by the drastic increase of contaminants in tissue (Table 2). Thus, toxic effects to sediment-dwelling organisms such as G. mirabilis at SFB-SM are highly likely (Hwang et al. 2008).

Static Measurements

SFB exhibited smaller age classes than TB (Fig. 5). Smaller size was correlated with higher levels of metallic contaminants (Fig. 7). Study results are consistent with previous G. mirabilis investigations. Size class structure monitoring in three southern California estuaries (Alamitos Bay, Ballona Wetland, and Mugu Lagoon) revealed that mean fish size was highest at the least contaminated site (Ballona Wetland) and smallest at the most contaminated site (Alamitos Bay Forrester et al. 2003). In addition to resident fish species such as G. mirabilis, size class monitoring has also been a successful metric for seasonal estuarine fish species. Size class structure of the juvenile common sole (Solea solea L.) indicated ecosystem quality in the Bay of Biscay, France (Le Pape et al. 2003).

Vital Rates

Recruitment rates were highest at contaminated site in 3 years out of 5 years. In addition, abundance was lower in SFB. The life history strategy of G. mirabilis is density dependent: a stable population has little room for recruitment since males compete for and establish territory for breeding, while YOY migrate throughout less desirable habitat until better-quality territory becomes available. New recruitment occurs when older individuals die, freeing up new territory. Since SFB exhibited higher recruitment rates than TB (Fig. 6), populations can be inferred to be less stable in contaminated habitats.

Growth rate (k) in SFB was slower than TB, while the natural mortality rate (M) was higher. Growth rates have been compared in G. mirabilis caged studies in southern California. Growth rate was negatively correlated with elevated chlordane levels, and total combined contaminants explained a negative change in length (Forrester et al. 2003). At SFB-SM, chlordane exceeded PELs and was determined to be a contaminant of concern (Hwang et al. 2006a) since it was readily bioavailable (Hwang et al. 2008, Table 2). Higher mortality rates and lower abundance in SFB may suggest lower survival due to poor habitat quality. Faster growth rate in TB may suggest that habitat quality is superior to SFB. Faster early life history growth rates have been linked with increased survival in many marine (Hovenkamp 1992; Meekan and Fortier 1996) and estuarine species (Sirois and Dodson 2000; Rosenberg and Haugen 1982). Younger and smaller life stages of fishes are more sensitive to toxic effects of contaminants (Grossel et al. 2007). In this study, slower growth rates in contaminated marshes suggest that younger life stages (which are more susceptible to toxic contaminant effects) are exposed to contaminants over a greater period of time, possibly leading to increased mortality.

The most dramatic observation throughout the study period was the complete absence of G. mirabilis in 2006 at SFB-SM. Year 2006 received the greatest amount of rain out of the sample period (Fig. 8), likely washing down the greatest pulse of contaminants in the study period. Typically, urban stormwater runoff contains high levels of toxic chemicals that are predominantly associated with particles (Hwang and Foster 2006, 2008) and can cause adverse affects on organisms in receiving watersheds (Carr et al. 2000; Bay et al. 2003). Geographical distribution patterns of PAHs in SFB-SM (Hwang et al. 2006a) indicate that SFB-SM was highly affected by stormwater runoff from nearby urban areas and adjacent historical industrial sites. As a euryhaline species, G. mirabilis is tolerant of freshwater (Todd and Ebeling 1966). Daily age analysis revealed that YOY ranging in length from 60 to 80 mm SL is approximately 6 to 8 months old. This suggests that individuals observed in August hatched between December and April. Hatch date conceivably co-occurred with high pulses of freshwater outflow (and contaminants) in 2006. Since contaminant levels are much higher in SFB-SM than other study marshes, this could have been above tolerance levels of YOY present during large-freshwater-outflow events. Another possibility is that fecundity and reproduction were negatively affected by contaminants in SFB-SM. Elevated PCB levels in fish eggs have been correlated with poor hatching success (Thompson et al. 2007). Increased levels of lead in gonads of Tetractenos glaber (the smooth toad fish) were associated with decreased oocyte diameter and density, leading to a decrease in reproductive success (Alquezar et al. 2006). SFB-SM contains elevated levels of both lead and PCBs (Hwang et al. 2006a, b), which could negatively affect fecundity and reproductive success.

Conclusions

The objective of this study was to determine the utility of using G. mirabilis population static measurements and vital rates as bioindicators of ecosystem quality. The most contaminated site (SFB-SM) contained the least and smallest fish. The least contaminated site (TB-TP) exhibited the highest G. mirabilis abundance and largest fish. Recruitment rates were highest at contaminated sites (SFB-SM and SFB-WM) in 3 years out of 5 years, suggesting a lack of adult survival. Growth rate was faster and mortality was lower in less contaminated sites in TB than more contaminated sites in SFB, suggesting that better habitat quality supports healthier populations.

References

Alquezar, R., S. Markich, J. Booth, and J. David. 2006. Effects of metals on condition and reproductive output of the smooth toadfish in Sydney estuaries, southeastern Australia. Environmental Pollution 142(1): 116–122. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2005.09.009.

Anderson, S.L., G.N. Cherr, S.G. Morgan, C.A. Vines, R.M. Higashi, W.A. Bennett, W.L. Rose, A.J. Brooks, and R.M. Nisbet. 2006. Integrating contaminant responses in indicator salt marsh species. Marine Environmental Research 62: S317–S321. doi:10.1016/j.marenvres.2006.04.011.

Araujo, F.G. and W.P. Williams. 2000. Fish assemblages and indicators of water quality in the middle Thames Estuary, England (1980–1989). Estuaries 23: 305–317. doi:10.2307/1353323.

Balling, S.S., T. Stoehr, and V.H. Resh. 1980. The effects of mosquito control recirculation ditches on the fish community of a San Francisco Bay salt marsh. California Fish and Game 66(1): 25–34.

Bano, N., A. Smith, W.A. Bennett, L. Vasquez, and J.T. Hollibaugh. 2007. Dominance of mycoplasma in the guts of the longjaw mudsucker, Gillichthys mirabilis, from five California salt marshes. Environmental Microbiology 9: 2636–2641. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01381.x.

Bay, S., B.H. Schiff, and K. Washburn. 2003. Water quality impacts of stormwater discharges to Santa Monica Bay. Marine Environmental Research 56: 205–223. doi:10.1016/S0141-1136(02)00331-8.

Bennett, W.A., and P.B. Moyle. 1996. Where have all the fishes gone? Interactive factors producing fish declines in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Estuary. 75th Annual Meeting of the Pacific Division/American Association for the Advancement of Science

Bowe, R. 2005. Ravaged roost. Terrain Winter.

Carr, R.S., P.A. Montagna, J.M. Biedenbach, R. Kalke, M.C. Kennicutt, R. Hooten, and G. Cripe. 2000. Impacts of stormwater outfalls on sediment quality in Corpus Christi Bay, Texas, USA. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 19: 561–574. doi:10.1897/1551-5028(2000)019<0561:IOSWOO>2.3.CO;2.

Cope, J.M. and A.E. Punt. 2007. Admitting aging error when fitting growth curves: an example using the von Bertalanffy growth function with random effects. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 64: 205–218. doi:10.1139/F06-179.

Desmond, J.S., J.B. Zedler, and G.D. Williams. 2000. Fish use of tidal creek habitats in two southern California salt marshes. Ecological Engineering 14: 233–252. doi:10.1016/S0925-8574(99)00005-1.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Region 9 News Release. State cleanup abandoned mine that threatened Tomales Bay ecosystem. http://yosemite.epa.gov/opa/admpress.nsf/89745a330d4ef8b9852572a000651fe1/468eacaabb9e7c83852570d8005e137c!OpenDocument.

Forrester, G.E., B.I. Fredericks, D. Gerdeman, B. Evans, M.A. Steele, K. Zayed, L.E. Schweitzer, I.H. Suffet, R.R. Vance, and R.F. Ambrose. 2003. Growth of estuarine fish is associated with the combined concentration of sediment contaminants and shows no adaptation or acclimation to past conditions. Marine Environmental Research 56: 423–442. doi:10.1016/S0141-1136(03)00004-7.

Goksoyr, A., J. Beyer, E. Egaas, E.G. Bjorn, K. Hylland, M. Sandvik, and J.U. Skaare. 1996. Biomarker responses in flounder (Platichthys flesus) and their use in pollution monitoring. Marine Pollution Bulletin 33: 36–45. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(96)00131-2.

Grossel, M., J. Blanchard, K.V. Brix, and R. Gerdes. 2007. Physiology is pivotal for interactions between salinity and acute copper toxicity to fish and invertebrates. Aquatic Toxicology 84: 162–172. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.03.026.

Higashi, R.M., T. Cassel, P.G. Green, and T.W.-M. Fan. 2005. 13C-tracer studies of soil humic substructures that reduce heavy metal leaching. In Subsurface contamination remediation: accomplishments of the Environmental Management Science Program, ACS Symposium Series, vol. 904, ed. B. Edgar and Z. Tiffany. Washington DC: ACS. doi:2005.

Hornberger, M.L., S.N. Luoma, A. Van Geen, C. Fuller, and R. Anima. 1999. Historical trends of metals in the sediments of San Francisco Bay, California. Marine Chemistry 64: 39–55. doi:10.1016/S0304-4203(98)80083-2.

Hovenkamp, F. 1992. Growth-dependent mortality of larval plaice Pleuronectes platessa in the North Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 82: 95–101. doi:10.3354/meps082095.

Hwang, H.-M. and G.D. Foster. 2006. Characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban stormwater runoff flowing into the tidal Anacostia River, Washington, DC, USA. Environmental Pollution 140: 416–426. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2005.08.003.

Hwang, H.-M. and G.D. Foster. 2008. Polychlorinated biphenyls in stormwater runoff entering the tidal Anacostia River, Washington, DC, through small urban catchments and combined sewer outfalls. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A 43: 567–575. doi:10.1080/10934520801893527.

Hwang, H.-M., P.G. Green, and T.M. Young. 2006a. Tidal salt marsh sediment in California, USA. Part 1: Occurrence and sources of organic contaminants. Chemosphere 64: 1383–1392. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.12.024.

Hwang, H.-M., P.G. Green, R.M. Higashi, and T.M. Young. 2006b. Tidal salt marsh sediment in California, USA. Part 2: Occurrence and anthropogenic input of trace metals. Chemosphere 64: 1899–1909. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.01.053.

Hwang, H.-M., P.G. Green, and T.M. Young. 2008. Tidal salt marsh sediment in California, USA: Part 3. Current and historic toxicity potential of contaminants and their bioaccumulation. Chemosphere 71: 2139–2149. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.01.005.

Hwang, H-M., P. G. Green, and T.M. Young. 2009. Historical trend of trace metals in a sediment core from a contaminated tidal salt marsh in San Francisco Bay. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 31: 421–430. doi:10.1007/s10653-008-9195-4.

Kneib, R.T. 1997. The role of tidal marshes in the ecology of estuarine nekton. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review 35: 163–220.

Le Pape, O., J. Holley, D. Geurault, and Y. Desaunay. 2003. Quality of coastal and estuarine essential fish habitats: Estimations based on the size of juvenile common sole (Solea solea L.). Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science 58: 793–803. doi:10.1016/S0272-7714(03)00185-9.

Lobry, J., L. Mourand, E. Rochard, and P. Elie. 2003. Structure of the Gironde estuarine fish assemblages: A comparison of European estuaries perspective. Aquatic Living Resources 16: 47–58. doi:10.1016/S0990-7440(03)00031-7.

Mathieson, S., A. Cattrijsse, M.J. Costa, P. Drake, M. Elliott, J. Gardner, and J. Marchand. 2000. Fish assemblages of European tidal marshes: a comparison based on species, families and functional guilds. Marine Ecology Progress Series 204: 225–242. doi:10.3354/meps204225.

McIvor, C.C. and W.E. Odum. 1988. Food, predation risk, microhabitat selection in a marsh fish assemblage. Ecology 69: 1341–1351. doi:10.2307/1941632.

Meekan, M.G. and L. Fortier. 1996. Selection for fast growth during the larval life of Atlantic cod Gadus morhua on the Scotian Shelf. Marine Ecology Progress Series 137: 25–37. doi:10.3354/meps137025.

Meng, L., P.B. Moyle, and B. Herbold. 1994. Changes in abundance and distribution of native and introduced fishes of Suisun Marsh. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 123: 498–507. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1994)123<0498:CIAADO>2.3.CO;2.

Methven, D.A., R.L. Haedrich, and G.A. Rose. 2001. The fish assemblage of a Newfoundland Estuary: Diel, monthly and annual variation. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Science 52: 669–687. doi:10.1006/ecss.2001.0768.

Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA). 1999. Overview of San Francisco Bay sport fish contamination and response activities. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, California Environmental Protection Agency, Oakland, CA, USA.

Orsi, J. (ed). 1999. Report on the 1980–1985 fish, shrimp, and crab sampling in the San Francisco Estuary, California. http://www.estuaryarchive.org/archive/orsi_1999

Rose, W.L., J.A. Hobbs, R.M. Nisbet, P.G. Green, G.N. Cherr, and S.L. Anderson. 2005. Validation of otolith growth rate analysis using cadmium-exposed larval topsmelt (Atherinops affinis). Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 24: 2612–2620. doi:10.1897/04-516R.1.

Rosenberg, A. and A.S. Haugen. 1982. Individual growth and size-selective mortality of larval turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) reared in enclosures. Marine Biology 72: 73–77. doi:10.1007/BF00393950.

San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board (SFBRWQCB). 1999. Bay protection and toxic cleanup program: regional toxic hot spot cleanup plan. Oakland: San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board.

SFEI 1997. What about the marshes? The Wetlands Pilot Study. RMP News 3: Issue 2.

Sirois, P. and J. Dodson. 2000. Critical periods and growth-dependent survival of larvae of an estuarine fish, the rainbow smelt Osmerus mordax. Marine Ecology Progress Series 203: 233–245.

Spies, R.B. and D.W. Rice. 1988. Effects of organic contaminants on reproduction of the starry flounder Platichthys stellatus in San Francisco Bay. Marine Biology 98: 191–200

Talley, D.M. 2000. Ichthyofaunal utilization of newly-created versus natural salt marsh creeks in Mission Bay, California. Wetlands Ecology and Management 8: 117–132.

Thompson, B.E. and S. Lowe. 2004. Assessment of macrobenthos response to sediment contamination in the San Francisco Estuary, USA. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 23: 2178–2187.

Thompson, J.K., and F.H. Nichols. 1984. Benthic macrofauna of a south San Francisco Bay, California, mud flat, 1974 to 1983: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report p. 84–759, 200 p.

Thompson, B., T. Adelsbach, C. Brown, J. Hunt, J. Kuwabara, J. Weale, H. Ohlendorf, S. Schwartzbach, R. Spies, and K. Taberski. 2007. Biological effects of anthropogenic contaminants in the San Francisco estuary. Environmental Research 105: 156–174.

Todd, E.S. and A.W. Ebeling. 1966. Aerial respiration in the longjaw mudsucker Gillichthys mirabilis (Teleostei: Gobiidae). Biology Laboratory of Woods Hole 130: 265–288.

US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 1997. The incidence and severity of sediment contamination in surface waters of the United States. Vol 1: National sediment quality survey. EPA-823-R-97-006. US Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Science and Technology, Washington, DC.

Walker, B.W. (ed). 1961. The ecology of the Salton Sea, California, in relation to the sport fishery. California Department of Fish and Game Fish Bulletin 113: 1–204

Weisel, G.F. 1947. Breeding behavior and early development of the mudsucker, a gobiid fish of California. Copeia 1947: 77–85.

West, J.M. and J.B. Zedler. 2000. Marsh-creek connectivity: fish use of a tidal salt marsh in Southern California. Estuaries 23: 699–710.

Yoklavich, M.M., M. Stevnson, and G.M. Cailliet. 1992. Seasonal and spatial patterns of ichthyoplankton abundance in Elkhorn Slough, California. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science 34: 109–126.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Science to Achieve Results Estuarine and Great Lakes (EaGle) Coastal Initiative through funding to the PEEIR Consortium (#EPA/R-82867601). Research activities conducted in Tomales Bay were under the National Marine Sanctuary Permit (#GFNMS-2002-005). Thanks to Charleen Gavette (NMFS Southwest Region) for assistance with figures, David Martasian for initial project development, Jessica Burton for review of drafts, Blythe Marshman for assistance in the field. Anonymous reviewers greatly improved the quality of the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

McGourty, C.R., Hobbs, J.A., Bennett, W.A. et al. Likely Population-Level Effects of Contaminants on a Resident Estuarine Fish Species: Comparing Gillichthys mirabilis Population Static Measurements and Vital Rates in San Francisco and Tomales Bays. Estuaries and Coasts 32, 1111–1120 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-009-9177-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-009-9177-5