Abstract

The study examines the Israeli Government Loans for SMEs in 2015. Our findings are based on three surveys. A business survey of 384 businesses that were granted a Government loan, a business survey of 99 businesses that were granted loans but decided not to take them and a survey of 50 loan consultants who advised those businesses about their eligibility and the Terms and Conditions of the loans. We tested Loan Adjusted Additionality and Loan Baseline Additionality and found that 53% of loans taken from the Government Loans Foundation (GLF) are additional loans. SMEs would not have taken a loan, or any part of one, if not for the Government Loans Foundation Scheme. Our contribution to the literature is by including Indirect Additionality, demonstrating the importance of the GLF Scheme, not only by assisting SMEs in their financial planning and growth but also, by signalling early stage business resilience, reducing the risks for commercial banks through regulated, financial due diligence. This outcome expands the pool of SMEs which have access to free market loans and has the potential to improve their survival rate, thus fostering economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Israeli Government Loans Foundation (GLF) for small and medium businesses (SMEs) has been implemented in its current format since April, 2012, by the Ministry of Economy and Industry and the Ministry of Finance, with a number of changes made in 2016. The Fund’s main objective is to assist SMEs with economic justification to access a loan that can support its growth potential in terms of sales and employability. Assisting those businesses is conceivable by providing Government guarantees (to reduce the risk that banks take upon themselves) and reducing the costs of the bank’s financial assessment.

The Government’s guarantees for a business loan remove a critical barrier for businesses which are economically viable, but for various reasons, are considered risky and therefore, cannot raise capital from commercial banks. A secondary objective of the Foundation is to contribute to improving the business loans structure by transferring part of the credit from short-term to medium-term (more than three years).

The Foundation provides a credit committee which decides loans applications. The committee is composed of one bank representative, one GLF representative and one representative of the public. The committee is advised by a co-ordination body in its role to supervise the execution of the whole process of the loan from the application stage, through providing the loan, to managing the payments. This co-ordination body also provides the committee with a financial and market review of the business, with a recommendation of whether to provide the loan for the applicant’s business.

Businesses which apply for a GLF loan must obtain the co-ordinating body’s recommendation and the credit committee’s recommendation for the loan amount. In the second stage, the businesses approach the bank with GLF guarantees for the specific credit conditions. Each loan can amount to up to NIS500,000 for businesses with a turnover of up to NIS6.25 Million per annum, and up to 8% of total turnover for businesses with NIS6.25 – NIS100 Million turnover. The loan is provided for a period of five years, with an additional half a year’s grace period. Typically, a business with turnover of up to NIS25 Million would pay a loan commission of 1%; 1.5% for a business with NIS25-NIS50 Million turnover, and 2% for businesses with turnover above NIS50 Million. The banks would also pay the Government a commission. Businesses which applied for a refinancing loan, or for investment purposes, would need to provide guarantees for up to 25% of the loan. Early stage businesses are required to have only 10% guarantees for loans up to 300,000, while the Government will guarantee 85% of the loan. For bigger loans, guarantee terms are similar for larger and established businesses.

1.1 SMEs in the Israeli economy and their financial sources

In Israel, like in many countries, SMEs play an important role in the economy. In 2015, SMEs accounted for 99.5% of 518,135 businesses and 61.1% of the business sector employees (Small Medium Business Association (SMBA) 2015). The Small and Medium Business Association (SMBA) definition for an SME is a business with 20 to 99 employees. Using the OECD definition for SMEs which includes companies with up to 249 employees, the results show they account for an even larger share of the economy, with SMEs accounting for 99.8% of all employer businesses in Israel, 68.7% of the business sector workforce and 62.3% of business economy value added (OECD 2016) (Table 1).

In Israel, bank credit is the main instrument used to fund SMEs and over 80% of SME credit is derived from this source. The remaining 20% tends to come from sources such as suppliers, institutes, funds, private credit companies, angel investors, VC funds, credit card companies and the emerging crowd funding platforms (Small Medium Business Association (SMBA) 2015). In general, the leading source is credit card companies which, until recently, were owned by the commercial banks. VC funds target a small number of high-tech companies. Crowd funding is not yet sufficiently developed to be considered a significant source. However, in 2017, the Government’s ‘Economic Committee’ approved regulation allowing crowd fund raising platforms to not be listed as credit rating companies, aimed to ease their ability to operate (‘The Knesset’, The Israeli Parliament website, June 2017).

The banking sector provides half of total business credit (411 out of 800 Billion ILS in 2015). Unlike large businesses which receive half of their credit from non-banking sources, SMEs depend mostly on bank credit. There is information asymmetry between SMEs and the banking system which causes difficulties with risk assessment and providing adequate loans.

According to SMBA, the private sector reacted to the public sector initiative to significantly increase Government guaranteed loans from 27 to 257 ILS millions, and from 2007 to 2016, the outstanding business loans for SMEs rose by 52% from 169,300 to 256,820 NIS millions accordingly, and their share of total outstanding business loans rose from 40.9% to 61.6%.

1.2 The purpose of this paper

The main purpose of this paper is to estimate the additionality of the GLF for SMEs. In particular, estimating the rate of businesses that were eligible for GLF loans which would not have been offered a loan by commercial banks, or at least, would not have received the credit conditions which the GLF offered. A second purpose of this paper is to examine the loan condition improvements that the businesses received because of Government guarantees for their loan. Our examination includes not only businesses which took a GLF loan, but also, businesses that were guaranteed a loan but decided to retrieve their application from the GLF and apply for a loan from a commercial bank, trying to match the loan Terms and Conditions (T & C). By capturing this, we can demonstrate that the GLF scrutiny process for SME financing and business plans has provided Indirect Additionality for SMEs. This is the first attempt to evaluate the GLF performance and we hope it will give policy makers a better, more concrete picture of the programme on a micro business level.

2 Literature review

The key point in evaluating Government guaranteed loan funding is to assess its value added effect or additionality. Aligned with the World Bank principles, the financial additionality refers to incremental credit given for business which includes an improvement in the financing T & C such as loan size, costs, maturity date, collateral required and the process of obtaining the loan. Economic additionality refers to the benefit of obtaining Government guaranteed loans or to their economic impact by creating jobs through improving investment and growth. Formerly, most of the financial additionality assessments relied on qualitative information in the form of interviews with bankers, business owners and other parties, for their opinion regarding the granting, or rejection, of a loan in the absence of a Government plan. A prominent and pioneering work by KPMG (1999) performed a combined methods evaluation of the LGS (Loan Guarantee Scheme) UK programme’s additionality, using two complementary approaches: in-depth interviews of borrowers and the views of lenders regarding the process of applying for and approving a loan through the programme and a survey among business owners who received the programme’s loans guarantees. This approach could be biased for several reasons. It could be biased due to: i) the borrower’s optimism regarding their ability to receive a loan even without the guarantee to divert the choice selection bias; ii) inherent selection bias of those who applied for a loan; iii) lack of reporting bias.

Studies that followed the KPMG study adopted this approach and examined the additionality in other countries. For example, Riding et al. (2007), carried out a qualitative evaluation of the Fund’s supplemental funding for small businesses in Canada. Their interviews provided rich data regarding the process of application submission for the programme and helped to create a classification of various types of supplementation (full funding supplementation, part-time supplementation and qualitative additions i.e., improvement of loan terms). The findings from this study showed that there was full funding supplementation in 39% of the cases and partial supplementation in 42%. In addition, 58% of participants reported some type of premium loan supplementation.

A more comprehensive methodology is the comparison approach in which there is a control group of businesses which received programme guarantees. For example, Riding and Haines Jr (2001) studied the additionality for Canadian businesses by controlling companies’ ages. Similarly, Saldana (2000) compared the collateral value of businesses which received a loan on bail against those without bail. In a later study, based on KPMG (1999), Boocock and Shariff (2005), who conducted an analysis of the financial and economic increment of Government guarantees in Malaysia, developed a framework based on 800 business observations. The sample was distributed into two groups: one group of businesses that had no financial additionality and a second group with partial, or full, financial additionality. The financial additionality rate obtained from the questionnaires was 54%. In a logistic regression, a set of variables, such as business size, loan size and ethnic background, were found to be significant. Cowling (2010), conducted a comprehensive study in the UK to assess financial additionality. They examined how the fund changes the possibility of obtaining financing with 441 businesses which received Government guaranteed loans. Those businesses were asked whether they would have obtained a loan without the Government guarantees. The findings were that 79% experienced financial additionality, meaning that without the loan guarantees, the businesses would not have secured a loan. It was also found that 76% of businesses which received Government guaranteed loans testified that they did not have any financial alternatives and 63% reported that they had to apply for a Government guaranteed loan because they were in their early stages and could not provide data to reflect their risks.

In recent years, data became more accessible. Both Riding et al. (2007) and Seens and Song (2015) based their studies on large data sets and found significant results with respect to productivity and business size contribution to financial additionality while the former found that loan additionality was 67%. Financial additionality is normally analysed on microlevel data (i.e., business performance), such as cross section panel data, document growth and performance indicators, before and after participating in a Government guaranteed loan programme (Bradshaw 2002; Heshmati 2008). However, not all studies chose microlevel data and some studies examined macrolevel variables such as regional growth and the rate of businesses which participate in a Government guaranteed loan programme. The challenge in such macro evaluation is in attributing the regional success to the specific Government programme rather than other, regional variables. In our study, we focus mainly on the assessment of the financial additionality of the specific Government scheme but we also provide a more general, economic additionality analysis.

3 Methodology

3.1 Loan application, flow chart

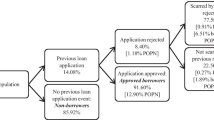

Our examination of the GLF loans additionality focuses on stage 11 in the flow chart. Decision point 11 is when, in order to obtain a loan, a business has to go through the GLF, and this is mostly fed from decision points 4, 5 and 8. In decision point 4, the fund contribution is twofold: first, by providing risk assessment for applicants and recommendations to the banks and second, reducing risks by providing the guarantees. In decision points 5 and 8, GLF contribution is by reducing risks through providing the guarantees (Graph 1).

3.2 In-depth interviews

As a basis for evaluating the financial additionality of the Government guarantees fund, 19 in-depth interviews were conducted with the financial advisors from MaofFootnote 1 and with the Director of Maof. We also interviewed the CEOs and deputy CEOs at Government approved consultancies who had provided their services to businesses between the years 2012–2014. The interview goals were to understand the considerations of businesses in taking a loan, the loan process and the business’s economic contribution in obtaining a loan.

3.3 Loan additionality

As we explained earlier, our goal was to measure GLF loan Additionality. According to the interviewee responses, we could identify whether it was a fully Additional loan, partially Additional (i.e., if a portion of the loan was provided by the bank), or whether it was not Additional at all. We differentiate between two forms of Additionality: first, ‘Direct Additionality’ i.e., the additional loan the GLF provided; second, the GLF loans that were withdrawn by businesses, what we have called ‘Indirect Additionality’.

Full Additionality for guaranteed loans was defined as the outcome of the following scenarios:

-

1.

The business applied for a commercial bank loan before contacting the GLF and the bank rejected its application.

-

2.

The business did not apply for a commercial bank loan because they knew the credit terms or they knew they would be rejected.

-

3.

The bank sent the business to the GLF because, according to the opinion of the business, the bank would not have provided a full loan, or if it did, the conditions would be unfavourable, forcing the business to reject the loan.

Partial Additionality occurs when one of the four conditions above is met and the business could have guaranteed a loan from the bank but chose just to borrow part of the money because of the loan T & C.

Not Additional loan is when the business decided to take a full loan from a commercial bank.

Our Additionality analysis is based on two types of measurement. Baseline Additionality (Boocock and Shariff 2005), relates to the actual credit provided by the GLF as opposed to the loan the bank would have provided, regardless of whether the business acquired the loan from the GLF or the bank. The second Additionality measurement is Adjusted Additionality which includes scenarios where a business could have secured a bank loan, but for some reason, decides not to take it (or part of it).

3.4 Key findings which fed into the survey planning

The risk assessment was mostly based on critical KPI such as bounced cheques and whether there were any restrictions on their bank account. The majority of financial advisors prefer to direct SMEs with guarantees to the bank, mostly to ease the bureaucratic process, and sometimes, because the bank provides better T & C. However, in some cases, financial advisors refer SMEs to the Government Fund (rather than directly to a bank) in order to improve the business credit line. According to one of the consultancies, businesses which worked with their bank for over five years, or had an annual turnover of NIS10 Million and above, could borrow money directly from the bank (with no Government guarantees). However, the T & C would be worse with the Government guarantees.

As regards improving loan T & C, half of our interviewees argued that 50% of businesses they offered consultancy to would not have guaranteed a loan from a commercial bank. They also said that a third of businesses would be given less favourable conditions from a commercial bank with respect to duration and interest rate. With additional loans, in some cases, the commercial bank would offer a partial loan which sent the business to the Government Loan Fund as another financial source.

Regarding early stage businesses, in most of our interviews, it was apparent that the GLF contribution is crucial for early stage businesses which struggle to obtain financing through commercial banks. Those interviewees who were consultants, nearly always sent loan takers to get the GLF evaluation first, in order to undertake the scrutiny examination which the commercial bank would not have done and just priced the loan with a high premium, to reflect the high risk. In some cases, commercial banks do not simply send loan applicants for the GLF scrutiny process, they also often amend their offer following it.

With respect to educating the industry, the standard process conducted by the GLF helps SMEs in improving their financial reporting capabilities, and thus, allows commercial banks to work better, asking for the necessary documentation and reporting templates.

Following our preliminary findings from the interviews conducted, we first decided to test the GLF Additionality for SMEs by surveying SMEs which had approached the GLF and were not rejected. This group was divided into two: those who show that their last dealing with GLF stops following their approval and those which stopped the process themselves even though the GLF did not reject them. The novelty of this work is by incorporating data about SMEs which initiated a loan process with the GLF, that is, not only incorporating those who were granted applications. It allowed us to include a scenario where a business would not have been granted a bank loan without the scrutiny of a Governmental body.

4 Descriptive statistics

Our sample includes 483 businesses, out of which, 384 businesses were guaranteed a loan (type A) and 99 which withdrew from the GLF loan (type B). Table 2 describes businesses’ characteristics, the sample and population size. We can see that there is not much difference between the characteristics of type A or B businesses. Businesses of both types were more likely to be from services and trade industries and most of the businesses that approached the GLF were LTD companies. The most common loan amount ranged from between NIS100,000 to NIS500,000 (exchange rate, during 2015 1US$ ranged between 3.5NIS to 3.9 NIS).

5 Findings

5.1 Additionality for guaranteed loans

Out of all the businesses that were guaranteed a GLF loan, 65% of them did not even approach a bank before applying to the GLF. 20% were sent to the GLF by the bank, 10% were provided a type of loan and 4% were rejected by the banks before approaching the GLF. Table 3 below provides detailed Additionality factors which classify Additionality levels.

We can see from Table 3 that for 34 businesses (9%), we cannot determine whether there is any Additionality for the GLF. With respect to Full Additionality and Partial Additionality, we summarised all observations in Graph 2 below to illustrate the proportions.

25 businesses in our sample argued that they took the GLF loan, even though the bank offered them the same conditions, or they did not approach the bank, even though they thought they could have guaranteed a bank loan fully. This was because of GLF preferred T & C such as interest rates and extended loan duration. 15 businesses said they took the loan to reduce their debt to the bank or to spread their financial resources. Looking only at the cases where businesses approached the bank, we found that the Additionality value was higher at 35% for Full Additionality, 22% for Partial Additionality, and 43% for no Additionality. If we extrapolate our findings to the general population of 3330 businesses which applied for a GLF loan, between December 2014 and September 2015, we can estimate that 1060 loans were fully Additional, 715 were partially Additional and 1560 were not Additional.

5.2 Sensitivity test companies and consultancies’ survey

During this study, we ran three sensitivity tests with respect to Additionality. One test confirmed the the responses of those businesses with consultants who assisted them in their GLF application process. The second test was conducted through credit supply, only (using the business survey) testing Baseline Additionality by analysing the business survey questions which related to the business opportunity to guarantee a loan from alternative sources, other than the bank. Finally, a direct question in the business survey asked what the business would have done if the GLF had not existed.

Table 4 shows that 51% of responses about Additionality in both surveys (Businesses and Consultants) are matching (marked in green). 14% of responses were contradictory (in red) and in 23% of the cases, the Additionality varies between Full Additionality and Partial Additionality. In 11% of the cases, Additionality varies between Partial Additionality and no Additionality. This show that there are some differences between the views of businesses and the consultants’ views about Additionality. However, in 74% of the cases, the classification is either similar or identical. We try to better illustrate this in Graph 3 below.

We can see in Graph 3 that the contribution of adding the consultants’ survey has a stronger effect on Partial Additionality. Adding the consultant survey responses results in 7 percentage points lower for Full Additionality than the business survey response, at 25%. However, it is higher for Partial Additionality by 18 percentage points at 39%. As a result, the total number of businesses which classified Full Additionality or partial Additionality has increased by 11 percentage points, reaching 64% (rather than only 53% from the business survey). This finding supports the hypothesis that businesses tend to be more optimistic about their ability to guarantee a loan than their consultants may have thought.

5.3 Additionality analysis by business characteristics

In Table 5, we provided Additionality controlling for Business Characteristics. This Table relates to the Additionality loan rate rather than the volume of Baseline Additionality, that is, the extra credit supplied by the bank.

First, we can see from Table 5 that the Additionality ratio for businesses which applied for a loan is higher for recently established businesses, more than any other reasons for borrowing money. However, this finding was not significant. The significant business characteristics we found (5% significance, chi square test) were business type, number of FTE (to proxy business size) and the business annual turnover. Business age was found to be significant but in 10% significance level, similarly loan volume (loan volume is highly correlated with the business annual turnover). The rate of Additionality (full and partial) is 63% of businesses against 48% only for LTD companies. The rate of additional loans (full and partial) for micro businesses (up to 4 FTE) is significantly higher (59%) than for larger businesses.

We also found that annual turnover is negatively correlated with the rate of GLF loan Additionality, that is, the ‘stronger’ the business is with a high turnover, the less likely it would apply for a loan. The loan Additionality for businesses with up to NIS1 Million annual turnover is 62% against 50% for businesses with a higher turnover of NIS1–10 Million, 40% for businesses with more than NIS 10Million and only 19% for businesses with more than NIS20 Million. 58% of businesses aged up to 5 years were guaranteed additional loans. This finding was 10% significant. 48% of older businesses were granted additional loans.

5.3.1 Newly established businesses and business size

In Graph 4, we show the Additionality for newly established businesses against other businesses.

We can see that the percentage of full, additive loans is 6 percentage points higher for newly established businesses than for older businesses. However, the rate of non-additive loans (partial or full) among newly established businesses is 7 percentage points lower than for older businesses. Thus, we conclude that Additionality is more important for newly established businesses than for other active businesses. These findings support the in-depth interview findings.

5.4 Loan baseline additionality

The total volume of Baseline Additionality provided for our sample businesses is NIS55,381,000, that is around 30% of total loans provided to those businesses. On average, business additional loans would be around NIS184,000. The loan additionality that we present here (measured by volume) is lower than the loan additionality that we measured by number of loan (full additionality or partial, 32% and 21% respectively). We attribute this finding to the fact that for smaller loans, additionality is at a higher rate than for large loans. In order to check the robustness of our findings, we examined the Baseline Additionality of the consultants’ survey. We compared Baseline Additionality in two surveys (businesses and consultants). Our findings suggest no significant difference between the surveys with respect to Baseline Additionality (44% in the business survey against 42% in the consultants’ survey). This is in line with findings described in Graph 3.

5.5 Businesses that did not apply for a Bank loan (before contacting GLF)

As seen in Table 3, 65% (248 businesses) did not approach a bank before contacting the GLF. From our consultants’ survey, we learned that the bank loan process is ‘easier’ than the GLF loan process, thus, businesses which have guarantees and need their loan fast prefer to apply for a bank loan. However, there are reasons why a business would prefer a GLF loan. Around a third of our consultants said that they would recommend a business to go through the GLF process to improve its future financial portfolio. From our business survey, we learned that 59% of businesses thought that the T & C for GLF loans were better than those of the bank and 32% decided to go with the GLF despite the longer loan process (Graph 5).

In addition, 13% of businesses which did not apply for a bank loan believed that the bank would not provide them with the loan they needed and 14% argued that their financial advisor had sent them to the GLF. Those businesses were asked why they thought the bank would not lend them money. In Table 6, we present the distribution of answers to this question. We can see that the main reason is that the business is in the early stages of its establishment (27%). Some reported that the reason concerned their industry field and their loan payment regime. Businesses that were not in their early stages argued that it has to do with the unique characteristics of the business (21%), the business credit portfolio (17%), low securities (16%) or predicted low loan return payments or low turnover (9%).

5.6 Indirect baseline additionality

Out of 99 businesses which withdrew their applications from the GLF, 32 borrowed money from a bank, 65 businesses decided not to borrow money and two borrowed money from other sources. In Table 7, we summarise the 32 business opinions about the GLF role in guaranteeing a bank loan.

We can see that the majority of businesses believed that the GLF did not help them to secure a bank loan: only 16.7% thought it was helpful, to some extent. However, when we asked the same question in the consultants’ survey, about those businesses which secured a bank loan, the GLF role seemed much more significant in that process. Six out of the eight consultants answered that the GLF was very helpful, or extremely helpful, in securing a bank loan. Four of them justified this by the detailed business plan the businesses prepared beforehand with the GLF, prior to withdrawing their application from the GLF. Another indirect Baseline Additionality was caused by the GLF’s role in raising awareness among businesses about their ‘free market’ options, that is, their eligibility for a bank loan, following a careful analysis of their finances.

5.7 Interest rate and loan duration

According to our business survey, an average GLF loan annual interest rate was 4.16% over 4.93 years (we included GLF fees, based on the business annual turnover), while for an average bank loan, the business needs to pay an annual interest rate of 4.57% over 4.89 years. Interest rate difference was found significant with a 1% significance (t test). In 47% of the cases, the GLF interest rate was better than the bank. Regarding the loan duration, we did not find significant differences: 93% of businesses said the bank would have offered them the same loan duration. Table 8 below describes the differences for a direct loan provided by the GLF or by banks The data was based on both surveys (businesses and consultants). We can see the preferred interest rate that the GLF provided, however, we also noticed the variance between businesses’ responses and those of the consultants. The businesses underestimated the differences compared to the consultants. Either way, both groups of interviewees acknowledged that the GLF provided preferred interest rates.

6 Summary and conclusions

Our purpose was to evaluate the GLF loan scheme Additionality for SMEs. In order to do that, we conducted 19 in-depth interviews with different stake holders who assist businesses in their loan applications. This helped us to understand the process, the challenges and barriers in the loan process, and thus, helped us design our surveys for businesses and consultants. Those surveys allowed us to evaluate how the GLF assisted them in improving the direct loan T & C (direct and indirect effect). We present below our main findings and conclusions.

6.1 GLF loan additionality

We learned from our business survey that 53% of GLF loans are additional, 32% fully additional and 21% are partially additional. Extrapolating our findings to the general population of 3330 businesses which applied for a GLF loan, we can estimate that 1060 loans were fully additional, 715 were partially additional and 1560 were not additional. The literature suggests that additionality is overestimated when the loan taker, the businesses, needs to estimate their ability to secure a loan. However, when we cross referenced these findings with our consultants’ survey, we can still see the significance of GLF additionality, with a total of 64% additionality (25% full additionality and 39% partial additionality).

These findings are in line with the in-depth interviews where around half of our interviewees claimed that businesses which secured a loan through the GLF would have not secured a loan with a bank at all, nor with the same T & C. They also argued that for around a third of businesses, banks offered loans with a significantly higher interest rate which made businesses reject the loan.

6.2 Additionality by business characteristics

We found that Baseline Additionality for businesses is 63% but only 49% for LTD companies and 59% for micro businesses. We also found that annual turnover is negatively correlated, with the rate of GLF loan additionality, that is, the ‘stronger’ the business is with a high turnover, the less likely it would be to apply for a loan. The loan additionality for businesses with up to NIS1 Million annual turnover is 62% against 50% for businesses with a higher turnover of NIS1–10 Million, 40% for businesses with more than NIS 10Million and only 19% for businesses with more than NIS20 Million. 58% of businesses aged up to five years, were guaranteed an additional loan, (this finding was 10% significant). 48% of older businesses were granted additional loans.

We conclude that the GLF scheme contribution is much more apparent for businesses which would normally have characteristics that would prevent them from securing a bank loan (such as recently established businesses, very small businesses, businesses with a small turnover etc). In that sense, GLF, as a Government intervention, balances a market failure where market forces would either have asymmetric information and thus, will not reach equilibrium, and as an outcome, will not reach an optimisation point. Or, it is because market forces are more risk averse and the Government role is to provide a guarantee and share the risk in order to grow and scale up SMEs.

6.3 Direct additionality

Based on the in-depth interviews we conducted and analysed from both surveys, we could demonstrate the GLF additionality not only through improvement of the bank loan T & C, but also, by including businesses that would not have taken a loan for any of the desired reasons such as growth, expansion or to establish a new business. In that respect, guaranteeing those businesses, together with a robust scrutiny process, using this vehicle, the Government has assisted the private market, helping it to expand to a higher production possibility frontier curve that would mean economic growth.

6.4 Indirect additionality

We learned, from our in-depth interviews, that the GLF scheme has indirect additive value because in some cases, for a business which started a loan process with the GLF, the bank was willing to match the T & C of the GLF scheme. This would not have happened without the scheme. We also highlight the fact that the GLF exists with a set process and T & C; it pushes the banks to compete with each other and with the scheme for those businesses. We acknowledge that we did not cover businesses which withdrew their applications from the GLF before reaching the evaluation committee stage. Thus, we are aware that we might have selection bias in our sample. However, most businesses which withdrew their applications following the committee decision decided not to take the loan from other sources either. From the consultants’ survey, we learned that there is a strong connection between securing a direct loan from the bank and GLF involvement. The particular reason is that the bank approved the loan for the business plan which the GLF assisted in drawing up for the business. This would provide the bank with better details about the business and its associated risks. Consultants also highlighted the ‘business education’ element when businesses are forced to regulate their financial and business documentation and panning. This might not only assist them with the current loan they apply for, but also, help their long-term strategy.

Notes

Maof is a government agency of local business development services centres. It is placed in the Ministry of Economics.

References

Boocock G, Shariff M (2005) Measuring the effectiveness of credit guarantee schemes: evidence from Malaysia. Int Small Bus J 23(4):427–454

Bradshaw TK (2002) The contribution of small business loan guarantees to economic development. Econ Dev Q 16:360–369

Chandler V (2012) The economic impact of the Canada small business financing programme. Small Bus Econ 39(1):253–264

Converse J, Presser S (1986) Survey questions: handcrafting the standardized questionnaire. Sage, Newbury Park

Cowling Marc (2010) Economic evaluation of the Small Firms Loan Guarantee (SFLG) scheme, Report commissioned by the UK Department of Business Innovation and Skills

Kang JW, Heshmati A (2008) Effects of credit guarantee policy on survival and performance of SMEs in Republic of Korea. Small Bus Econ 31:445–462

KPMG (1999) An evaluation of the small firms loan guarantee scheme, Department of Trade and Industry, London (1999)

OECD (2016) SME and entrepreneurship policy in Israel 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris

Riding A, Haines G Jr (2001) Loan guarantees: costs of default and benefits to small firms. J Bus Ventur 16(6):595–612

Riding A, Madill J, Haines G Jr (2007) Additionality of SME loan guarantees. Small Bus Econ 29(1–2):47–61

Saldana C (2000) Assessing the economic value of credit guarantees. Journal of Philippine Development 49(XXVII) No.1

Seens D, Song M (2015) Requantifying the rate of incrementality for the Canada small business financing program. Ottawa: Industry Canada. Available online on the SME Research and Statistics Website. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/061.nsf/vwapj/RRI_CSBFP-NQTA_PFPEC_eng.pdf/$file/RRI_CSBFP-NQTA_PFPEC_eng.pdf

Small Medium Business Association (SMBA) (2016) A periodic Report of the state of SMEs in Israel (Hebrew). http://www.economy.gov.il/sba/Doch_SBA_2016.pdf

Storey DJ (2000) Six steps to heaven: evaluating the impact of public policies to support small businesses in developed economies. In: Sexton DL, Landstrom H (eds) Handbook of entrepreneurship. Blackwells, Oxford

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Adjusted additionality and baseline additionality

Adjusted additionality and baseline additionality

Table 9 below is a classification of interviewees’ answers to: Adjusted Additionality and Baseline Additionality, with respect to Full Additionality/Partial or None.

From Table 9, we can see that when we look at Baseline Additionality, we cannot determine GLF loan additionality for 6% (22 businesses). Looking at Adjusted Additionality for 9% (34 businesses), we cannot determine GLF loan additionality. Graph 6 below helps to narrow down the differences for Full Additionality, Partial Additionality and No Additionality, with respect to Baseline Additionality and Adjusted Additionality, across all businesses.

We can see in Graph 6 that nearly two thirds of business loans were fully additional, based on the Adjusted Additionality definition, while only 21% were fully additional by the Baseline Additionality definition. Most businesses which classified the level of Additionality differently, were placed either in Full Additionality or Partial Additionality.

In 48 businesses, their loan Additionality was greater as defined by Baseline Additionality rather than Adjusted Additionality (NB: a business which was offered a bank loan would not be included under Baseline Additionality, but if the business was offered a loan but rejected it, this would be defined under Adjusted Additionality). 25 businesses claimed to have taken a GLF loan even when the bank offered them a loan (or they thought they could obtain a loan but did not approach the bank), because they preferred the better T & C that the GLF proposed (Graph 7).

We can see that businesses in an early stage of establishment are more likely to take a loan than other businesses, in particular, when measuring their loan additionality with Baseline Additionality. The same applies for micro businesses as opposed to small, or medium sized, businesses.

We also found that the difference between the two measurements - Baseline and Adjusted - is more significant for mature businesses because the banks would be more likely to offer a mature business a full, or partial, loan but the business can choose not to take it. Medium sized and mature businesses can easily reject such a loan unlike micro, or newly established, businesses.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

H. Rubin, T., Ben-Aharon, N. Additionality of government guaranteed loans for SMEs in Israel. J Econ Finan 45, 504–528 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-021-09538-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-021-09538-8