Abstract

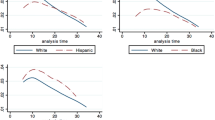

This paper investigates post-2000 trends in homeownership rates in the US by immigrant status, race, and ethnicity. Homeownership rates for most groups examined rose during the housing boom of the early and mid-2000s but fell during and after the housing bust. By 2015 homeownership rates had fallen below year 2000 levels for most groups but not all. In particular, some Asian immigrant groups experienced sizable gains in overall homeownership rates and in regression-adjusted differences relative to white non-Hispanic natives. Some other immigrant and minority groups also made gains relative to white non-Hispanic natives. We document and discuss these changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This includes American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands, and other US possessions.

Include Boston, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Bakersfield, Bridgeport, El Paso, Fresno, Hartford, McAllen, Modesto, New Haven, Oxnard, Rochester, San Antonio, Stockton, Tucson, Urban Honolulu, Worcester, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, Riverside, San Diego, and Washington.

Include Baltimore, Denver, Minneapolis, Philadelphia, Portland, Sacramento, San Jose, Seattle, Tampa, Atlanta, Austin, Charlotte, Las Vegas, Orlando, Phoenix, Cape Coral, Columbus, Durham, Greensboro, Indianapolis, Lakeland, Nashville, Raleigh, Salt Lake City.

Singer (2015) uses recent and historical Census Bureau data to classify MSAs and offers more objective criteria than Painter and Yu (2014). See https://www.brookings.edu/research/metropolitan-immigrant-gateways-revisited-2014/ for details

Age of the householder is defined as a vector of binary variables indicating if the householder is 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, or 55–64 years of age. We include 27 education dummy variables for each category in the IPUMS variable educd. We include 5 dummies for marital status and 25 dummies for household size.

The broad definition has 9 groups: white non-Hispanic natives, white non-Hispanic immigrants, Asian non-Hispanic immigrants, Asian non-Hispanic natives, Hispanic natives, Hispanic immigrants, Native Americans, black non-Hispanic natives, and black non-Hispanic Immigrants.

Our detailed groups are intended to provide a richer analysis of the heterogeneity among Asians and Hispanics, while recognizing that very small groups prevent precise estimates. Our analysis using detailed groups excludes white non-Hispanic immigrants, Native Americans, black non-Hispanic natives, and black non-Hispanic Immigrants given the small sample sizes among sub-groups within these. We examine 20 detailed Asian and Hispanic groups: Chinese non-Hispanic immigrants, Chinese non-Hispanic natives, Filipino non-Hispanic immigrants, Filipino non-Hispanic natives, Indian non-Hispanic immigrants, Indian non-Hispanic natives, Korean non-Hispanic immigrants, Korean non-Hispanic natives, Vietnamese non-Hispanic immigrants, Vietnamese non-Hispanic natives, Other Asian non-Hispanic immigrants, Other Asian non-Hispanic natives, Cuban Hispanic immigrants, Cuban Hispanic natives, Mexican Hispanic immigrants, Mexican Hispanic natives, Puerto-Rican born persons, Puerto-Rican Hispanic natives, Other Hispanic immigrants, Other Hispanic natives. The Puerto-Rican born persons are those that are born in Puerto Rico and are also Puerto Rican ethnicity. The Puerto-Rican Hispanic natives are those that are not born in Puerto Rico but are Puerto Rican ethnicity.

2015 was the most recent ACS microdata year available at the time of our analysis. 2007 was chosen as a pseudo-midpoint that also reflects the median year of the homeownership rate peak across groups.

To center log household income at the mean for the base group, we first computed the mean for the base group and then subtracted this mean from the log household income for all individual observations. Centering in this way does not affect the coefficients for the group*income interaction terms, but it facilitates the group intercepts to be more comparable to the model without the interaction terms.

References

Acolin A, Bricker J, Calem P, Wachter S (2016) Borrowing constraints and homeownership. Am Econ Rev 106:625–629

Bauer TK, Cobb-Clark DA, Hildebrand VA, Sinning MG (2011) A comparative analysis of the nativity wealth gap. Econ Inq 49:989–1007

Bayer P, Ferreira F, Ross SL (2016) The vulnerability of minority homeowners in the housing boom and bust. Am Econ J Econ Pol 8:1–27

Borjas GJ (2002) Homeownership in the immigrant population. J Urban Econ 52:448–476

Bostic RW (2003) A test of cultural affinity in home mortgage lending. J Financ Serv Res 23:89–112

Bostic RW, Surette BJ (2001) Have the doors opened wider? Trends in homeownership rates by race and income. J Real Estate Financ Econ 23:411–434

Brueckner JK (1997) Consumption and investment motives and the portfolio choices of homeowners. J Real Estate Financ Econ 15:159–180

Chatterjee S, Zahirovic-Herbert V (2014) A road to assimilation: immigrants and financial markets. J Econ Financ 38:345–358

Constant AF, Roberts R, Zimmermann KF (2009) Ethnic identity and immigrant homeownership. Urban Stud 46:1879–1898

Coulson NE (1999) Why are Hispanic- and Asian-American homeownership rates so low? Immigration and other factors. J Urban Econ 45:209–227

Coulson NE, Dalton M (2010) Temporal and ethnic decompositions of homeownership rates: synthetic cohorts across five censuses. J Hous Econ 19:155–166

Courchane M, Darolia R, Gailey A (2015) Borrowers from a different shore: Asian outcomes in the U.S. mortgage market. J Hous Econ 28:76–90

Davidoff T (2006) Labor income, housing prices, and homeownership. J Urban Econ 59:209–235

Dawkins CJ (2005) Racial gaps in the transition to first-time homeownership: the role of residential location. J Urban Econ 58:537–554

Deng Y, Ross SL, Wachter SM (2003) Racial differences in homeownership: the effect of residential location. Reg Sci Urban Econ 33:517–556

Faber JW, Ellen IG (2016) Race and the housing cycle: differences in home equity trends among long-term homeowners. Hous Policy Debate 26:456–473

Gabriel SA, Painter G (2008) Mobility, residential location and the American dream: the intrametropolitan geography of minority homeownership. Real Estate Econ 36:499–531

Gabriel SA, Rosenthal SS (1991) Credit rationing, race, and the mortgage market. J Urban Econ 29:371–379

Gabriel SA, Rosenthal SS (2005) Homeownership in the 1980s and 1990s: aggregate trends and racial gaps. J Urban Econ 57:101–127

Gabriel SA, Rosenthal SS (2015) The boom, the bust and the future of homeownership. Real Estate Econ 43:334–374

Haan M (2007) The homeownership hierarchies of Canada and the United States: the housing patterns of white and non-white immigrants of the past thirty years. Int Migr Rev 41:433–465

Henderson JV, Ioannides YM (1983) A model of housing tenure choice. Am Econ Rev 73:98–113

Hilber CAL, Liu Y (2008) Explaining the black–white homeownership gap: the role of own wealth, parental externalities and locational preferences. J Hous Econ 17:152–174

Huszár ZR, Lentz GH, Yu W (2012) Does mandatory disclosure affect subprime lending to minority neighborhoods? J Econ Financ 36:900–924

Krivo LJ, Kaufman RL (2004) Housing and wealth inequality: racial-ethnic differences in home equity in the United States. Demography 41:585–605

Logan JR, Zhang W, Alba RD (2002) Immigrant enclaves and ethnic communities in New York and Los Angeles. Am Sociol Rev 67:299–322

McConnell ED (2015) Hurdles or walls? Nativity, citizenship, legal status and Latino homeownership in Los Angeles. Soc Sci Res 53:19–33

McConnell ED, Akresh IR (2008) Through the front door: the housing outcomes of new lawful immigrants. Int Migr Rev 42:134–162

McConnell ED, Marcelli EA (2007) Buying into the American dream? Mexican immigrants, legal status, and homeownership in Los Angeles County. Soc Sci Q 88:199–221

Megbolugbe IF, Cho M (1996) Racial and ethnic differences in housing demand: an econometric investigation. J Real Estate Financ Econ 12:295–318

Mishkin FS (2011) Over the cliff: from the subprime to the global financial crisis. J Econ Perspect 25:49–70

Mundra K, Oyelere RU (2017) Determinants of homeownership among immigrants: changes during the great recession and beyond. Int Migr Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12311

Mussa A, Nwaogu UG, Pozo S (2017) Immigration and housing: a spatial econometric analysis. J Hous Econ 35:13–25

Myers D, Lee SW (1998) Immigrant trajectories into homeownership: a temporal analysis of residential assimilation. Int Migr Rev 32:593–625

Painter G, Yu Z (2010) Immigrants and housing markets in mid-size metropolitan areas. Int Migr Rev 44:442–476

Painter G, Yu Z (2014) Caught in the housing bubble: immigrants’ housing outcomes in traditional gateways and newly emerging destinations. Urban Stud 51:781–809

Painter G, Gabriel S, Myers D (2001) Race, immigrant status, and housing tenure choice. J Urban Econ 49:150–167

Painter G, Yang L, Yu Z (2004) Homeownership determinants for Chinese Americans: assimilation, ethnic concentration and nativity. Real Estate Econ 32:509–539

Ruggles S, Genadek K, Goeken R, Grover J, Sobek M (2015) Integrated public use microdata series: version 6.0 [dataset]. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

Shlay AB (2006) Low-income homeownership: American dream or delusion? Urban Stud 43:511–531

Singer A (2015) Metropolitan immigrant gateways revisited, 2014. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, Metropolitan Policy Program. https://www.brookings.edu/research/metropolitanimmigrant-gateways-revisited-2014/. Accessed December 1, 2017.

Smith MM, Hevener CC (2014) Subprime lending over time: the role of race. J Econ Financ 38:321–344

Tesfai R (2016) The interaction between race and nativity on the housing market: homeownership and house value of black immigrants in the United States. Int Migr Rev 50:1005–1045

Turner TM (2003) Does investment risk affect the housing decisions of families? Econ Inq 41:675–691

Turner TM, Smith MT (2009) Exits from homeownership: the effects of race, ethnicity, and income. J Reg Sci 49:1–32

Wheeler CH, Olson LM (2015) Racial differences in mortgage denials over the housing cycle: evidence from U.S. metropolitan areas. J Hous Econ 30:33–49

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Results with heterogeneous income effects

Appendix: Results with heterogeneous income effects

As noted briefly in Section 4.4, we also conducted additional analysis in which we re-estimated the full specifications in Tables 1 and 3 but also allowing log household income to have differing effects for each immigrant and minority group. To do so, we first centered log household income at the mean log household income for the base group, native non-Hispanic whites. We then interacted the centered log household income with dummy variables for each immigrant and minority group and included these in the models for the additional analysis. Results corresponding to Tables 1 and 3 are reported in Appendix Tables 5 and 6, respectively. Columns 1, 2 and 3 for each Appendix Table are for years 2000, 2007, and 2015, respectively. These include all of the socioeconomic characteristic controls and MSA fixed effects in the full specification of those tables and also add the income*group interaction terms.

The coefficients on the group dummies in the Appendix Tables are overall very similar to their counterparts in Tables 1 and 3 estimated without the interaction terms. Many of the group dummy coefficients and standard errors are exactly the same as their counterparts in Tables 1 and 3. None of the group dummy estimates go from statistically significant to not statistically significant and none of the significant coefficients change signs. Thus, all of the main conclusions above are qualitatively robust to this alternative specification with income*group interaction terms.

The coefficient on log household income (not interacted) is statistically significantly positive in all 3 years with coefficients increasing from 0.040 in 2000 to 0.050 in 2007 and then falling to 0.038 in 2015. This captures the homeownership-income responsiveness of the base group, native non-Hispanic whites. The increase in 2007 indicates that homeownership responsiveness to income was especially strong in 2007 for the base group.

The income*group interaction coefficients are mostly negative and many are statistically significantly negative. In Appendix Table 5, the income*group interaction is only statistically significantly positive (at the 10 % level) for Hispanic immigrants in 2007; all other interactions in Appendix Table 5 are negative or not statistically significant. A negative group*income interaction term indicates that the homeownership decisions for members of the group are less responsive to household income than that of the omitted group, native non-Hispanic whites. The negative income interaction effect in Appendix Table 5 is largest for Native Americans in all 3 years, implying that Native Americans have a much smaller homeownership response to income than native non-Hispanic whites. We can compute the total effect of log income on homeownership for each group and year by summing the log income coefficient with the group*income interaction term. For example, for Native Americans in 2015, the total effect is 0.038 + −0.021 = 0.017, which is still statistically significantly positive based on the joint standard error. In fact, all of the total effects obtained in this way are statistically significantly positive at least at the 10 % level. Thus, the total effect of income on homeownership varies in magnitude across groups, but the direction is always positive. Income*group interaction results in Appendix Table 6 exhibit somewhat more heterogeneity. The coefficients are still largely negative, but the estimates are significantly positive in at least some years for Filipino immigrants, Vietnamese immigrants, other Asian natives, Cuban immigrants, and Puerto Rican born persons. These patterns suggest a nuanced story about how different immigrant and minority group homeownership outcomes respond to income. Future research should consider this nuance in more detail.

We also considered examining group interaction effects for other factors like age, education, and family structure. However, our main analysis controls for these factors using a large number of dummy explanatory variables. The main goal of our paper is to estimate and discuss differences in mean homeownership rates for a large number of immigrant and minority groups relative to native non-Hispanic whites, both unconditionally and conditional on a detailed set of socioeconomic characteristics. Including many dummy control variables is a useful approach for our main analysis because it allows for a flexible non-linear relationship between the explanatory factors and the dependent variable. However, it would be difficult to accurately and concisely report interaction effects for the interactions of many socioeconomic characteristic dummies with our group dummies because there would be so many interaction terms. Thus, we suggest that future research should consider examining group interaction effects for other factors like age, education, and family structure, but doing so may require adopting a different approach to measuring these socioeconomic factors than the approach taken here that uses a large number of detailed dummy variables. Alternatively, future research looking at interactions with detailed dummy variables could focus on one group or possibly a few immigrant and minority groups to limit the scope but increase the depth of analysis. Our analysis offers useful insights, but there is much more to be learned.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chakrabarty, D., Osei, M.J., Winters, J.V. et al. Which immigrant and minority homeownership rates are gaining ground in the US?. J Econ Finan 43, 273–297 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-018-9443-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-018-9443-0