Abstract

In large-scale surveys of both children and adults, self-rated health (SRH) based on questions such as “In general, how would you rate your health?” is a widely used measurement to assess individuals’ health status. However, while a large number of studies have investigated the health aspects people consider for their responses, and some studies show deeper insights into the assessment strategies in answering this question for adults, it is largely unknown how children assess their health based on those questions. Therefore, this study examines how children rate their health according to this question in a sample of 54 9- to 12-year-olds. By using techniques of cognitive interviewing and qualitative and quantitative content analysis, we investigate the health dimensions, health factors as well as different assessment strategies that children refer to in their self-assessment of general health. Our results indicate that children in this age group mostly refer to their physical health and daily functioning or consider health more non-specifically. They also show that children take into account a wide range of specific health aspects, with some minor differences between subgroups, especially by gender. Additionally, our study highlights that children use several assessment strategies. Finally, our results indicate that the majority of children assess their health only using one health dimension, but a substantial share of children reflect on several health factors and combine different assessment strategies. We conclude that children refer to comparable health dimensions and health factors, but use somewhat different assessment strategies compared with studies focusing on adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Studying children’s well-being is of high interest in various disciplines. A growing body of literature investigates the level of children’s well-being in different countries, examines the determinants and social inequalities (e.g., Bradshaw et al., 2007, 2013, Gilman & Huebner, 2003, 2006, Klocke et al., 2013). As part of children’s well-being, research also focuses heavily on children's health considering children’s own perceptions of their health referring to a wide range of survey instruments (e.g., Pollard & Lee, 2003). In large-scale surveys, self-rated health (SRH) is a widely used measurement to assess respondents’ health. Questions, such as “How would you rate your health in general?”, are commonly implemented in a large number of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in children, adolescents, adults, and the elderly to provide a global indicator for individual health (e.g., children and adolescents: HBSC (e.g., Inchley et al., 2016), KIGGS (e.g., Poethko-Müller et al., 2018), Millennium Cohort Study (e.g., Centre for Longitudinal Studies, 2023); e.g., adults: ESS (e.g., Eikemo et al., 2016), PSID (e.g., Andreski et al., 2009), BHPS (e.g., Institute for Social and Economic Research, 2023), SOEP (e.g., Ziebarth, 2009); elderly: SHARE (e.g., Jürges et al., 2008)). Although there is a wide range of different wordings of the question, all of them aim to efficiently assess individuals’ perceptions of their overall health status in a comparable way. It is argued that while responding to the question, individuals evaluate different dimensions of their health referring to, for instance, physical health, mental health, and daily functioning (Krause & Jay, 1994; Miilunpalo et al., 1997). Thus, beyond knowledge about objective health indicators such as medical diagnoses or laboratory examinations, these measurements also incorporate individuals’ interpretations of health. They refer to various facets of health-related information an individual has, for example, about their own health-related life style and practices, their health compared to the health of others at the same age, or health issues in the family (Lundberg & Manderbacka, 1996). Respondents thus create a comprehensive summary of their health resulting in high correlations with individual health conditions, mortality risk, and morbidity (Lee, 2014). Studies show that SRH is associated with individuals’ physical fitness, perceived energy levels, limiting longstanding illnesses, psychological distress, diabetes, epilepsy, coronary heart disease, respiratory symptoms, and mortality risk (Eriksson et al., 2001; Fosse & Haas, 2009; Manor et al., 2001; Schnittker & Bacak, 2014). As a result, in the empirical literature, SRH is argued to be a useful measurement for analyses addressing individuals’ overall health and mortality risk as well as to assess children’s perception about their health.

In contrast to the profound empirical evidence on the associations of SRH with objective health indicators, the way respondents assess their health is still rather elusive to the researcher. A growing number of qualitatively oriented studies address, therefore, the cognitive processes during the response to SRH questions. This strand of research examines how respondents define their health, how they select health-related information, assess its importance, and how they rank their own health, as well as how individual characteristics, social context, and observational context influence the individual's response to the question (for review see Garbarski, 2016). For adults, results indicate that respondents assess their health by evaluating their overall health condition based on the presence or absence of health problems and different health dimensions, e.g. physical or mental health. In addition, the majority of adults seem to evaluate their health based on factors of negative valence and presence as well as evaluation of their current and past state of health (e.g., Garbarski et al., 2017). The vast majority of these studies deals with adult respondents. Yet, little is known about the underlying processes in children’s answers to SRH. Only a small number of studies have investigated how children respond to those questions. Findings indicate that younger respondents (aged between 14 and 24) are more likely to include present health-related behaviors in their evaluation compared to older adults, who mostly refer to existing health conditions (for review and further evidence see Joffer et al., 2016). This raises the question, whether and how differences in cognitive processes result in different interpretations of the question and thus, whether SRH ratings are comparable between different age groups.

Based on underlying evaluation processes, individuals’ assessment of their health might diverge over the life course (Abdulrahim & El Asmar, 2012; Boardman, 2006; Chandola & Jenkinson, 2000). For example, given cognitive development in childhood and adolescence, individuals’ understanding of health and the complexity of cognitive processes change. Although children between the age of 7 and 11 have an impression of the causes and consequences of health, they develop a more complex understanding later in life. Therefore, in earlier stages of the life course, their ratings might be more related to noticeable or visible symptoms, diseases, illnesses, and health-related behaviors. In contrast, with increasing age, the abstraction level increases, and interdependencies between different health-related aspects and the experiences in daily life become more inherent in their health definition (Lohaus & Ball, 2006). Therefore, asking children and adolescents to rate their health might result in different assessment strategies compared to adults. Given the large volume of research on children and adolescents using SRH, further understanding of the cognitive processes that influence this age group's responses is crucial.

To our knowledge, no study exists on this matter so far; only very few studies have dealt with related questions. For example, in their valuable study, Joffer et al. (2016) investigate adolescents’ interpretations related to the question “A person may feel good sometimes and bad sometimes. How do you feel most of the time?”. The adolescent respondents interpreted the concept of “feel” in a very holistic way and referred primarily to mental and social aspects. As it was to be expected, when contrasting the concepts of “feel” and “health”, the authors found that the respondents assigned different meanings to these concepts. Consequently, the results provided by Joffer et al. (2016) are not transferable to questions that are more directly related to health, like in this study.

Given the lack of research on how children and adolescents interpret the question “How would you rate your health status in general?”, this study adds to the body of research accordingly for younger respondent groups. Using qualitative and quantitative content analysis of cognitive interviews, this study aims to shed more light on children’s responses to self-rated health measurements used in a large number of studies. It contributes to the question how children evaluate their own health based on this survey question as well as differences in evaluation strategies by gender, age and educational background. In addition, the study analyzes 54 children aged 9 to 12, providing insight into cognitive processes among younger age groups in relation to their responses to the question. In this regard, the present study follows the analytical strategy of Garbarski et al. (2017), which focuses, among other things, on health dimensions, health factors as well as the assessment strategy. This allows us to discuss our results in comparison to studies that focus on adults, so that we can obtain insights into whether children's response behavior follows similar or rather different patterns compared to adult response behavior.

2 Conceptual Framework

In literature, various disciplines provide their definition of health. In medicine, a biomedical perspective dominates, defining health as the absence of disease, i.e., pathological abnormalities. In the social sciences, by contrast, the focus is on a social understanding as well as on individual-subjective aspects of health (Richter & Hurrelmann, 2016; Wade & Halligan, 2017). Following the latter strand of literature, health can thus be defined as subjective health, which refers to the individual's assessment of health (Flick, 1998). The underlying theory assumes that an individual’s health is defined as one’s assessment based on their perceived health demands, potential, and available resources. Specifically, an individual’s health is their subjective health assessment by what they perceive is required of them in their daily lives (e.g. in school, at work or in the family), their biological (e.g. genetic dispositions and chronic diseases) and personal acquired health-related potential, and resources (e.g. physical abilities or social support) (Bircher, 2005).

Within this framework, subjective health can be further characterized by different health dimensions: We distinguish individuals’ physical and mental health, as well as aspects of daily functioning (Huber et al., 2011; Wilson & Cleary, 1995). Physical health is strongly linked to the medical perspective of health such as cell, organ, and system functioning. However, from a social science perspective that focuses heavily on individuals' perceptions, physical health tends to reflect individuals' views of their physical health limitations (e.g., in the form of physical symptoms that represent an “abnormal physical condition”) and not necessarily medically diagnosed illnesses (Wilson & Cleary, 1995).

Mental health relates to an individual's capacity to cope with stressful life events and challenging situations, manage social roles, solve problems, or respond flexibly to difficult situations. Mental health includes an individual's ability to deal with their emotions, empathize with others, and communicate with them (Galderisi et al., 2015; Huber et al., 2011). Thereby cultural and social contexts strongly influence definitions of mental health because they affect individuals’ perceptions of normality, proper behavior, and social roles. Thus, the individuals’ subjective mental health status includes their evaluations of positive and negative experiences, feelings of unhappiness, subjective vulnerability, and feelings of confidence (Bryant & Veroff, 1984), but also represent their perceived personal competence in handling life given internalized social and cultural beliefs, norms and values.

Daily functioning refers to an individual's ability to meet their daily needs, manage life with an appropriate level of independence, and fulfill social roles (Huber et al., 2011; Wilson & Cleary, 1995). Impairments in daily living represent a limitation of these individual abilities and are usually the result of physical or mental health limitations (Wilson & Cleary, 1995). In this context, the literature emphasizes that daily demands, perceived potential, and available resources influence individuals’ daily functioning. (Bircher, 2005; Wilson & Cleary, 1995).

The SRH measurement aims to capture the assessment of a person’s health status. It is assumed that respondents consider all three health dimensions, the individual requirements, opportunities and resources, in their answers. Likewise, researchers also expect that individuals evaluate their health in terms of perceived limitations or opportunities, demands, and resources for the three dimensions of health, thereby considering different health factors. Empirical literature as well as cognitive interviews in adults support these assumptions. Results indicate that individuals assess their health in terms of, for example, various specific or nonspecific health conditions, health behaviors, health care utilization, or physical functioning that are particular important to the individual (e.g., Garbarski et al., 2017; Krause & Jay, 1994).

When analyzing the cognitive processes of children’s ratings of SRH, we will build on previous research by adopting this conceptual framework and resulting analytical differentiation between health dimensions and specific health factors as further outlined in chapters 4.2 and 4.3.

3 Data and Methods

3.1 Cognitive Interviews

To investigate children’s interpretations of the SRH-question and to analyze their cognitive processes underlying their response, we used a qualitative research design and conducted semi-structured cognitive interviews. Cognitive interviews aim to analyze the comprehensibility, interpretation, and difficulties of a survey question, and to evaluate causes of problems in respondents’ answers (DeMaio et al., 1998; Conrad et al., 1999; Blair & Presser, 1993). They help to indicate whether a survey question leads to similar interpretations among respondents or causes problems in terms of misunderstanding, unintended or subgroup-specific interpretation. In addition, cognitive interviews show how social desirability might affect respondents’ answers to the question and examine whether response options fit the question. Furthermore, in combination with a semi-structured interview process, they allow for comparison between respondents’ answers and give the opportunity to ask for specific aspects of respondents’ answers more directly. Thus, they help to explore the respondent’s interpretation of the survey question, allow for the evaluation of the cognitive process while answering and can directly assess problems caused by the design of the question (DeMaio et al., 1998; Conrad et al., 1999; Blair & Presser, 1993). Consequently, cognitive interviews are a valuable approach to get deeper insights into children’s evaluations of their global health status.

In cognitive interviewing two different techniques are common in validating survey measurements (for review see Willis, 2004). The first common method is to ask respondents to think-aloud about all the different aspects that come to mind after they first hear or read the question. They are encouraged to talk particularly about ambiguous or unpleasant impressions, any thought that pops to mind about the clarity of the question, and any missing information related to the task, leading to rich and valuable insights into the respondent’s cognitive processes while answering the question. The second method is verbal probing. Following this method, researchers place probing questions after the actual survey question addressing the comprehension, category selection processes and general interpretations more directly. This allows to directly focus on different aspects in respondents’ answers and, thus, assures to get the information needed.

In cognitive interviews with children and adolescents, the verbal probing technique is more appropriate (Als et al., 2005). This is because the think-aloud technique places a high cognitive load on the respondents, as they must not only be able to think about these issues but also verbalize them. In contrast, the verbal probing technique guides respondents through the cognitive process and asks more directly about specific aspects related to the response process, thereby reducing the cognitive burden for the respondent (Miller et al., 2014). This technique might therefore lead to more valuable responses from children because they are more directly encouraged to talk about their thoughts on the survey question (DeMuro et al., 2012). Using verbal probing questions also helps the children to focus further on the interview, as probes provide new stimuli and motivate further reflection. Additionally, semi-standardized probing questions allow for addressing the different levels of children’s comprehension. They standardize aspects of the reflection about the cognitive process which avoids different foci in the interview due to differences between stages in the cognitive development of the children (Borgers et al., 2000; Als et al., 2005). As a result, we take advantage of the verbal probing technique in semi-standardized interviews to evaluate the cognitive processes of children in responding to the SRH-question.

3.2 Study Design

To investigate children’s cognitive processes while answering the question on self-rated health, we first asked children the initial survey question, how they would generally describe their state of health on a scale from “very good” to “very poor”. In a second step, we asked how difficult they found the question ranging from 1 (“very difficult”) to 4 (“very easy”). Finally, we used two probing questions to get a deeper understanding of children’s cognitive processes. First, we asked “What were you thinking about when you answered the question?”. Secondly, we asked “What does’state of health’ mean to you?” (for an overview see Table 1). Additionally, the interviewers were instructed to ask for further explanations if the child’s first answer was unclear. In doing so, however, they should take care not to overload the children cognitively. Thus, if a child seemed already very tired by the interview, unclear answers were also accepted without further inquiries.

3.3 Setting and Sample

The study was conducted at the Leibniz institute for educational trajectories in Bamberg, Germany. The present study was part of a larger project including cognitive interviews for different survey instruments related to the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS, Blossfeld & Rossbach 2019) with parents and their children between the ages of 9 and 12. Families were recruited from social networks of the research assistants involved in the project supplemented by a snowball procedure, aiming for an oversampling of families with migration background and lower socio-economic background in order to ensure sufficient variation of the sample with regard to these aspects. During the recruiting process, parents of children in the age between 9 and 12 years were asked if they were generally interested in participating in the study and whether the child is willing to take part in the survey. If they were interested, we asked them for a postal address to send some information material and a consent form for participation at home. The information material contained a short description of the NEPS, information about this sub-study, such as the aim of the cognitive interview, survey contents and conditions of participation, as well as information about a post survey reward worth 20 euros. The consent form included agreement to the type of data collection and data publication, and a request for some basic information for further contact. In addition, during the first contact, we asked for contacts to other families with children in the age between 9 and 12.

Based on the families recruited, we draw children from different school grade levels, different school tracks, and by gender. Table 2 shows descriptive results of our sample. The sample contains in total 54 children of which 30 are female and 24 are male. We asked 23 children of primary schools, one child attending a lower secondary school, seven children attending a middle secondary school, four children attending a combined secondary or comprehensive school and 18 children attending a higher secondary school. 16 children were in grade four, ten children in grade five, 16 children in grade six and 12 children in grade seven. 13 children had at least one parent that was born abroad and the largest part of the sample includes children with parents with a high educational level.

3.4 Data Collection

The cognitive pretests were conducted between August and October 2020. This period was characterized by measures to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as social distancing measures. Thus, possibilities for personal contacts were strongly limited. Therefore, although we planned the initial design based on face-to-face interviews, we conducted telephone interviews.Footnote 1 We employed five interviewers who were trained by research assistants of the responsible team for this study as well as conducted a small number interviews ourselves. The interviewers received a detailed manual that included all the information presented in the interview training, additional material for technical questions, explanations of special challenges of the survey, notes on the sample and the content of the interview, and special processing instructions. To ensure high quality of the interviews, the interviewers conducted test interviews. For the interviews they received the questionnaire in a printed version and were placed in quiet rooms. They recorded the interview with a dictaphone, but also made notes on problems encountered during the interview. After the first couple of interviews, they got a brief supervision by the scientific staff to reflect on problems and talk about challenges. We also carried out quality checks of the recordings to ensure compliance with the guidelines and standards.

The interviews were split up in two separate parts: one part addressing questions to the parent and one part for the cognitive pretests of survey questions for children and adolescents. Parents were asked for information about sociodemographic characteristics such as parents’ education, age, and the gender, migration background, attended school track and grade level of the child. They were also given a question and corresponding cognitive probes that were part of another cognitive evaluation. After interviewing the parents, the interviewers asked for the contact to the child and then proceeded to conduct the interview with the child. This part of the interview lasts about 19 (sd: 3.72) minutes on average. After the survey, each child received a voucher worth around 20 euros for different online services and department stores for their participation in the study.

After the field phase of the study, the interviewers transcribed the interviews based on the audio recordings. For the purpose of our study, we decided to transcript verbatim, including all spoken words, filling words or phrases, false starts, grammatical errors, and dialect. To ensure standardized transcription, we provided guidelines to the interviewers and quality checked the transcripts.

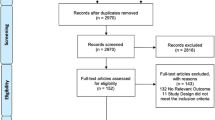

3.5 Data Analysis

To identify the different patterns of cognitive processes in answering the question, we analyzed children's answers to the probing questions by using methods for content analyses, while employing concept analysis techniques. Firstly, we extracted the mentioned concepts of all children with a valid response to the probes. Secondly, we categorized the responses based on a scheme developed concurrently to the analysis, having in mind the conceptual framework presented in chapter 2. Finally, we discussed the categorization within our research team to clarify different interpretations of children’s responses. We only evaluated answers to the probing questions, if children were able to reflect on the question. We did not consider answers of children who did not answer to the self-rated health question or did not know what to answer with regards to the probes. In addition, we excluded children from analysis who only repeated the content of the self-rated health measure, without giving any further explanation how they interpret the question or came to their answer.Footnote 2 We coded children’s response to the probing questions in an iterative process and revised coding schemes during data analysis.

Referring to the analyses of children’s explanations of how they rated their health status, we partly followed the analytical categories of Garbarski et al. (2017). Garbarski et al. (2017), firstly, extracted “types of health factors mentioned”, which represent all health factors, which were used by respondents to describe their health. These factors comprise, for instance, the presence or absence of different types of specific or unspecific health conditions, health behavior, health care utilization, physical functioning. Secondly, they extracted the valence of health factors mentioned, which represents respondents’ affective orientation to the health factor mentioned. Thirdly, they concentrate on the temporality of the health factor, e.g. whether respondents refer to past, present, or past to present.

When developing our coding schemes for the present study, we adopted the concept of health factors as well as the aspect of temporality. The final coding schemes are displayed in Tables 3 and 4. In the first part of our analysis we extracted the dimension(s) of health considered by our respondents. In line with our conceptual framework we analyzed whether a child referred to physical health, mental health, and/or daily functioning. To complement this, we summarized the statements of children who did not include a specific dimension in their assessment with the code “unspecific statement.” This first step provides a comprehensive picture on which health dimensions children primarily concentrate on their evaluations. In the second part of our analysis, following Garbarski et al. (2017), we built similar analytical categories in those aspects that proved comparable to their study. We ended up with four categories with two of them comparable to the study of Garbarski et al. (2017). One refers to the health factors mentioned by the children.Footnote 3 The other three analytical categories reflect children's assessment strategies (see Table 4). We identified three core aspects in children’s assessment strategies. First, the temporality of the assessment (i.e., whether a child reflects on past or presence health issues), second, the graduation of different levels by severity or frequency of health impairments, (i.e., whether a child assesses differences in health by severity or frequencies of health issues), and third, children's reference criterion in their self-evaluations (i.e., whether a child refers to the health of others, their own health in the past or to experienced conditions, or whether they provide a global statement without any specific reference).Footnote 4

In the third part of our analysis, we moved beyond the scope of previous studies and considered the multidimensional nature of children's responses. We analyzed the coding schemes not only separately, but also in light of the question whether and to what extent children combine different aspects in order to assess their health status. Specifically, we look at the multidimensionality of children’s answers in terms of the number of health dimensions they referred to, health factors they mentioned, as well as the multitude of strategies for their health assessment. Although not being perfectly associated to one another, multidimensionality may reflect complexity of children’s assessments.

Importantly, for both the unidimensional and multidimensional analysis of children’s health assessments, we investigated whether the process of assessment is eventually related to the actual evaluation of self-rated health. In addition, we analyzed potential group differences by gender, migration background, age, and parental education in order to investigate whether our data hints to any systematic differences between subgroups in their perceptions of health. For instance, some authors have raised concerns regarding the potential divergence in interpretations of the concept of health among various social and ethnic groups (Angel & Gronfein, 1988). Although previous research has indicated the validity of comparisons between different social and ethnic groups (e.g., Chandola & Jenkinson, 2000), these findings were exclusively established for adults, and not for younger age groups. Therefore, we address this matter in our analyses.

For all these steps, we provide the absolute and relative share of children belonging to the respective categories. We also provide quotes from children that illustrate the assignment of answers to the different categories exemplarily, present cross-tabulation results for children's ranking of their health, and give indication for differences by subgroups. For testing the significance of group differences by gender (boys vs. girls), age, migration background (at least one parent born abroad vs. both parents born in GermanyFootnote 5), and parental education (respondent parent with tertiary educational degree vs. respondent parent with less than tertiary degreeFootnote 6), we use Fisher’s exact test to account for the small sample size.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics

Corresponding to the self-rated health measurement, most children of the sample stated that they were in “very good” (35%) or “good” health (54%), with some children (9%) reporting mediocre health. Additionally, one child did not know how to rate the individual health status (see Table 5). With regard to individuals’ characteristics, we observe relatively more boys who stated “very good” health as well as “mediocre” health. In addition, younger children in our sample were more likely to rate their health as “good”, while older children aged 11 and 12 reported “very good” and “fair” health more frequently compared with younger children. With regard to migration background, the descriptive results show that children without migration background more frequently reported “good” health and less frequently “very good” health. Children with highly educated parents reported also less frequently “very good” health, but more often reported “good” health. In contrast, children in our sample with lower educated parents assess their health more frequently as “mediocre”.

Investigating the children’s reports about the perceived difficulty of the question, most of the children of the sample stated that it was “easy” (52%) or “very easy” (41%) to answer the question (see Table 6). However, four out of 54 children mentioned that answering the question was “difficult” or “very difficult”; two of them were unable to explain their answer to the self-rated health question subsequently. Regarding children’s gender, age, migration and educational background, cross-tabulation results do not reveal large or consistent differences of perceived difficulty of the question.

Regarding the probing question, most of the children could reflect on their cognitive process while answering the question and explain why they evaluated their health as “very good”, “good”, or “mediocre”. However, 12 (24%) of 53 children, who gave a valid answer to the survey question on self-rated health could not conclusively explain their answer. Either they indicated that they could not say what was in their mind, or that they were thinking about health but could not directly explain how they rated it. Thus, these children are not available for in-depth analysis of the cognitive processes. Note, however, that this does not necessarily mean that these children were unable to provide a valid answer to the initial question on SRH; only two out of these 12 children reported that they found answering the question on SRH difficult.

4.2 Health Dimensions

Based on the 41 children, who gave valid answers to the probing question, we firstly evaluated which health dimensions they addressed for the evaluation of their health status (Table 7, column 1). About half of the children (n = 22) considered physical health aspects for their health assessment. For instance, the children indicated that they thought about physical health impairments such as a cold, cough or a flu, a back condition, bad teeth, a stomach ache, an injury to their foot, nausea and malaise, diabetes, immunity to infections, or life-threatening illnesses. In addition, about 12 percent (n = 5) considered aspects of daily functioning in their self-evaluation. These children mostly referred to absences from school due to illness or limitations in leisure activities. Furthermore, a large proportion of the children (34%, n = 14) made an unspecific assessment and stated something like “how I feel”, “just does not feel healthy”, or “I'm actually always feeling great”. In addition, some children (12%, n = 5) did not consider a health dimension, but referred to health-related behaviors instead. Those children did not link the behavior they mentioned to any specific health aspect or outcome. Thus, we coded them as having no health dimension considered. Interestingly, none of the children with a valid answer to the probing question expressed having thought about mental health issues while evaluating their own health.

Cross-tabulation of the health dimensions with the actual SRH assessment indicate that children thinking about physical health or made an unspecific health statement appear to be more likely to report mediocre health (see Table 7). Moreover, children who provided an unspecific understanding of health seem to be the least likely to report very good health. However, it is not possible to assess any directions of causality of this association. We cannot tell whether different levels of SRH lead to different foci in the evaluation or vice versa. For instance, it may well be that children with health impairments focus on those when answering the probing questions, which leads to a focus on physical health.

With regard to the subgroup comparisons, the data indicates no differences by gender, age, migration background, or parents’ education (see Table 8).

4.3 Health Factors

While the first step of our evaluations shows that children refer most often to physical health and daily functioning, or think more generally about their state of health, the next step of analysis about the specific health factors mentioned by the children provides a deeper insight into the specific aspects that children considered in their evaluation (see Table 9). The majority of the children referred to affect. About 27 percent (n = 11) mentioned that they thought about how they felt. For instance, a girl (12 yrs.) referring to this category explained: “I've been thinking about whether I've been feeling bad lately or overall in some way.” Another girl (11 yrs.) stated that she thought “how I just always feel at the moment “. Descriptive results indicate that there are no systematic differences by children's gender, age, migration background, or parent’s education.

However, also a large number of children considered the presence or absence of diseases or illnesses to evaluate their health. About 17 percent (n = 7) indicated that they thought about temporary diseases. Those children mostly refer to colds or coughs. Evaluations based on this factor are like: “I was thinking that I am just healthy and not sick. Sometimes a cold, but currently also not at all.” (girl, 11yrs.). Another 10 percent (n = 4) considered chronic illnesses in their evaluation. Children doing so refer to illnesses such as diabetes, cancer, severe physical limitations, or directly defined chronic illnesses more generally. For example, one child mentioned in relation to this factor, “I just came to the conclusion that I am not chronically ill. So, I don't have a real illness that does not go away” (girl, 11yrs.). Even though a large proportion of children directly mentioned temporary diseases and/or chronic illness, an equally substantial number of children (24 percent, n = 10) used the term illness rather non-specifically. These children used the term “illness” without an example, as in the following statement by a girl (11 yrs.) “Well, I'm healthy, yeah, and I've never had any illnesses, yeah.”, or described “being sick” in general terms as in the statement by a boy (12 yrs.). Again, descriptive results indicate, that there are no systematic differences by children's gender, age, migration background, or parents education in referring to different types of illnesses.

In addition to considering current health and illnesses, a small proportion of children made reference to pain and symptoms (15%, n = 6), or injuries (7%, n = 3). Children who considered pains and symptoms either named the symptom directly, e.g., stomach ache, or used the word “hurt” to indicate pain. One child (boy, 11 yrs.), for instance, stated that he considered “that [he has] (…) a little stomach ache from time to time”. Another child (boy, 11yrs.) mentioned “I felt if anything hurt”. The three children, who consider injuries in their rating of health refer to examples of injuries at the time of the interview or events in the past. For example, one child (boy, 12 yrs.) stated “So I thought to myself when I got the question, I also thought to myself when I answered that I now also have a small injury on my heel and that's how I came to my answer.” Similar to the other health factors already mentioned, whether a child indicates pain and symptoms or injury does not appear to be related to gender, age, immigrant background, or parental education.

Despite considering different health conditions, about 20 percent (n = 8) of the children evaluated their health status based on their (positive) health-related behaviors, such as physical activity or daily diet. Some children argue, that they rated their health as “very good” or “good”, because they “[eat] per day a lot of vegetables and fruit and sometimes also some candy” (boy, 9 yrs.) or “do a lot of sports and so” (boy, 9 yrs.).

Finally, seven percent of children did consider other aspects in their health evaluation. For example, one child (boy, 11 yrs.) reported that he was thinking mostly about the Corona pandemic and that he feels bad at the moment because he can't go outside, and another child (girl, 11 yrs.) stated that one of the reasons she considered her health to be “good” was because her father always says she has a good immune function.

With regard to the health factors mentioned, we see that those children considering temporary diseases and their affect seem to rate their health more positively than children referring to other factors in their assessment (see Table 9). Furthermore, children who include pain and symptoms or injuries in their evaluations tend to report a lower health status. It might be that children with certain health problems focus their assessments on exactly those impairments; thus, the factors mentioned are more specific and at the same time, the rating of SRH is worse.

Despite these differences in health evaluations, we also see small variation by gender, migration background, and parents’ education (see Table 10). For instance, boys reported pain and symptoms slightly more often than girls. In addition, children of highly educated parents referred to injuries less often compared to children of less educated parents. Health assessments that considered affect were slightly more common among girls and children without migration background. However, all these differences are not statistically significant from zero.

4.4 Aspects of Assessment Strategy

When evaluating their individual level of health, children do not only use diverse health factors but also different assessment strategies. They differ in temporality, type of classification of the rank, and frame of reference (see Table 11). In terms of the time frame of their assessment, children either consider time in the past up to the time of the interview or the current status, or apply a more general time-independent assessment. While about 34 percent (n = 14) of children assessed their health based on past to current conditions, about 34 percent (n = 14) evaluated only their current status. Children, who assessed their health considering not only current but also past conditions, explain, for instance, “so far I have only been sick once, and before that I wasn't sick for ages. And therefore [I am] actually very healthy, I think” (boy, 12 yrs.). In contrast, children who mainly considered their current health stated things like “I sensed whether anything hurt or whether I felt unwell, whether I was nauseous or something, (...), and that's when I noticed that everything was actually okay” (boy, 11yrs.). The other children, however, do not refer in their explanation to an explicit time frame. They stated something like “because I do a lot of sports” or “whether I eat rather uh very much and very much sweet and so”. In the utilization of temporal references, however, we observe a difference according to the child's background. It seems that children from our sample whose parents have a high level of education are more likely to consider conditions from the past in their evaluation.

Regarding their ranking, some children explicitly used the severity and/or frequency of health conditions to rank their health. Some children (17%, n = 7) refer to the severity of diseases, illnesses, injuries, or pain and symptoms to explain how they got to their answer. Children referring to severity signal different levels by using words such as “serious” or “severe”, “(not) bad”, “mild”, “minor”, or “normal”. One child (girl, 11 yrs.), for instance, mentioned that she rated her health as “good”, because she is “not chronically ill” and has “no serious illness”, but she has “a lot of colds […].” Thus, she distinguished between severe illnesses and minor diseases. Although the common cold is reflected in her evaluation of health, a chronic or serious illness would make a significant difference for her. In the same vein, another child (girl, 12 yrs.) stated “Sometimes I have a cold but that is totally normal.” Consequently, she considered colds not as much as other (more severe) health conditions. Similarly, one child (girl, 9 yrs.) argued that she rated her health as “good” because at the time of the interview she had “a mild cold, but it's not bad”. Thus, she considered the severity of her cold when rating her health. These results suggest that some children made a distinction between different types of diseases and illnesses, and rated their health based on the perceived severity of conditions. These seem to be more likely for boys as descriptive statistics indicate that the boys in our sample use the severity of illnesses more frequently in their ratings than girls.

Another factor presented in children’s evaluation of their health status refers to the frequency of conditions. About 56 percent (n = 23) of children considered the frequency of illnesses to rate their overall health status. Children using this type of assessment strategy use words such as “often”, “seldom”, “sometimes”, “from time to time”, “never”, or “only once”. For instance, one child (boy, 10 yrs.) stated that he evaluated his health as “very good”, because he “was not very often sick”. Likewise, another child (girl, 10 yrs.) explained that she “was thinking about how um like which how often I'm about this healthy or not”. With regard to the children's characteristics, however, we see no systematic differences. Although, boys, children with migration background and with highly educated parents seem to use this type of classification more often, the differences are not statistically significant.

Apart from considering different types of temporality or different ways of classifying the rank of different health states, children also differ in their frame of reference. While some children use a comparison with other individuals as a reference (5%, n = 2), other children use a comparison with another state of themselves to assess their health (27%, n = 11). Children who compared their health with the health of others used one particular person as a reference. For instance, one child (girl, 10 yrs.) stated “one [child] of our class has diabetes, but I don't have it.” Another child (boy, 12 yrs.) mentioned “[I was thinking] about my grandfather, who had cancer and died of it. [Compared to him,] I am healthy.” In contrast, children, who explain their assessment by self-referencing use comparisons such as “except when I am sick”, “otherwise I'm fine”, or “pretty good, except for”. These children mostly seemed to have a better or worse condition in mind on which they rated their health. One child (girl, 12 yrs.), for example, stated: “Actually, I'm almost always fine, except when I'm sick or something.” Another child (boy, 10 yrs.), belonging to this group mentioned: “Except sometimes I fall down a lot, [then I'm] not so good anymore.” Notwithstanding, the majority of children made an unspecific statement without a direct reference criterion (58%, n = 24). Taken together, although some children use such a reference criterion, a large proportion of the children made a rather independent evaluation.

The strategy how children assess their health, however, seems to be related to their self-rated health status and there are some differences by children’s characteristics (see Tables 11 and 12). For example, current status ratings appear to be more prevalent with very positive ratings than with mediocre or good ratings. In addition, considering the severity of diseases seems to be linked to lower ratings, while the frequency of diseases is more part of good and very good evaluations. With regard to the reference frame, we see that comparison with others and self-referencing is more dominant in “very good” and “good” evaluations, while children who did not mention any reference frame refer more to the categories “good” and “mediocre”.

In addition, using a specific frame of reference differs slightly by children’s characteristics (see Table 12). Children with parents with higher education levels were more likely to use past to present evaluations. Boys as well as children with migration background were more likely to assess the severity of diseases and illnesses. In addition, boys were also more likely to base their assessment on the frequency of diseases, illnesses, injuries, pain, and symptoms, as well as children with parents with high education level and children without migration background were. Self-referencing was also performed more frequently by boys. Last but not least, explanations without naming the frame of reference were somewhat more frequent among girls, younger children, and children without an immigrant background.

4.5 Analysis of Multidimensionality

While the analysis of singular aspects of children’s health assessment yields interesting insights, we seek to enrich this analysis by addressing the matter of multidimensionality. There was great variation in patterns of combination of different aspects that children used in order to assess their health status. This applies to both health dimensions and health factors, as well as the combination of specific assessment strategies children applied. Thus, we first analyzed whether children used one single or multiple aspects with regard to (i) health dimensions, (ii) health factors, and (iii) assessment strategies. Referring to the coding schemes used in the previous analysis in Tables 3 and 4, we display the proportion of children with multidimensionality in the three domains, defined as referring to more than one coding scheme in the respective domain (see Table 13).

Only 15 percent of the children referred to more than one health dimension in their assessment, while the vast majority based their assessment on one single health dimension. Most children either referred to physical health, daily functioning, or used an unspecific definition of health. Among the children who combined multiple dimensions (n = 6), the majority referred to physical health combined with either daily functioning or an unspecific understanding of health. The number of health dimensions considered appears to be unrelated to children's ratings of health.

When it comes to specific health factors, 29 percent of the children (n = 12) took on a multidimensional perspective, referring to more than one health factor in their assessments. In contrast to the health dimension, there was no dominant pattern of combination of specific health factors among those who referred to more than one health factor. However, children’s consideration of more than one health factor in their health status evaluation appears to be related to their ranking of SRH: Two out of three children who reported mediocre health referred to more than one health factor in their assessment.

In terms of the assessment strategies, we focused on the two schemes temporality and graduation levels (severity)Footnote 7: 44 percent of the children referred to more than one aspect. Again, no dominant patterns of combinations were observed, apart from the fact that most, but not all, children referred to an evaluation of either their past or their present health status with regard to temporality. Secondly, most children who combined different strategies (n = 18), included the notion of frequency of health impairments in their assessment. Again, we see only small differences between children’s SRH in dependence of the number of assessment strategies. Our results indicate that a lower health rating seems to be associated with a combination of multiple assessment strategies. All children who rated their health status as only moderate used at least two different assessment strategies.

Finally, we combined these separate categories and computed an additive index of coding schemes that were mentioned in the children’s answers. In total, 16 coding schemes were included, while empirically, the maximum number of codes used in a statement was eight. Figure 1 provides an overview of the extent of multidimensionality. The majority of children referred to four to six coding schemes in their assessments.

Lastly, we explore potential differences in terms of gender, migration background, age, and parental education and analyze whether the multidimensionality of children’s assessment is eventually related to the actual evaluation of self-rated health. We differentiate whether children use a multidimensional approach in the respective domain (assessment based in more than one coding scheme) or not. Interestingly, boys and girls in our sample differ partly greatly in terms of multidimensionality in the three coding categories (see Fig. 2). With regard to the health dimensions, far more girls (21%) than boys (6%) use a multidimensional approach. While there are no gender differences in terms of health factors, we find a pronounced gender difference in the opposite direction for assessment strategies: While 65 percent of the boys in the sample used more than one assessment strategy, only 29 percent of the girls did so. Thus, there is no consistent gender difference with regard to multidimensionality: While there are pronounced gender differences in the single domains, they seem to largely cancel each other out and there is no consistent overall gender difference regarding the multiplicity of factors considered by children when assessing their health status. This is also reflected by rather similar mean values when we compare the additive index of multidimensionality covering all coding schemes for girls (mean = 3.4) and boys (mean = 4).

In addition, we found slightly higher levels of overall multidimensionality in the statements of children without migration background and with high parental education (see Table 14). As with gender, there were no consistent patterns in the single components of the health assessment: Among children with a migration background, the proportion of children who mentioned more than one health dimension as well as particular health factor is substantially lower than for children without a migration background. However, this is not the case for assessment strategies, where in both groups almost half of the children make reference to more than one strategy. None of the children with low or medium parental education (n = 9) included more than one health dimension in their response, but the proportion of children who mentioned more than one health factor was larger in this group than among the children with high parental educational background. When it comes to assessment strategies, the share of children who refer to more than one assessment strategy is higher among children of parents with high education. Again, there is no consistent difference in multidimensionality with regard to migration background and parental education, but any differences largely depend on the specific domain that is considered.

When comparing the overall multidimensionality score, the statements of boys, children without migration background, and with parents with high education show a slightly (but non-significant) greater extent of multiplicity of the factors that they base their health assessment on than the children in the respective reference group. Surprisingly, there was no evidence of an association with age, contradicting to what we initially had expected based on the theories of cognitive development. Assuming that multidimensionality is at least partly related to complexity of the ratings, it is surprising that multidimensionality does not increase with age.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

The aim of the present study was to investigate how children rate their health based on the frequently used survey question “In general, how would you rate your health?”. The study serves to provide a deeper understanding of cognitive processes in children while answering this question. Using cognitive interviews with children aged 9 to 12 years, we examined children’s use of health dimensions, health factors, and assessment strategies. Our results, firstly, show that self-rated health in children and adolescents seems to indicate primarily their physical health status, daily functioning as well as overall assessments, but not their mental health status. None of the children in our sample has referred to mental health. Secondly, the findings indicate that children do not only focus on broad dimensions such as physical health and daily functioning, but within these dimensions also take into account different specific health factors, such as temporary and chronic illnesses, health-related behaviors, affect, as well as injuries, pain and symptoms in order to evaluate their health. Thirdly, the findings highlight that children employ different assessment strategies regarding the temporal reference, graduation levels (severity), and the respective references frame when assessing their overall health status. They show that children use past to present evaluations to a similar extent as evaluations of their current status, assess the frequency of perceived impairments. Children only seldom make comparisons to others, but they refer more often to themselves or evaluate their health without an explicit frame of reference. Finally, our analyses indicate that children combine different dimensions, health factors, and assessment strategies when evaluating their health.

In addition, our results reveal that health scores vary partly with the health dimension addressed, the health factors, and the assessment strategies. For instance, we observed only little difference in SRH levels across the health dimensions, with more very positive, but also more mediocre ratings for children who reported thinking about their physical health. In addition, thinking about temporary diseases and daily affect seems to be inversely associated with children’s health ratings. The lower children’s health rank, the lower the proportion of children who report these factors. In addition, pain, symptoms, and injuries are more often part of a mediocre assessment of health. This suggests that this measure also distinguishes between different health conditions in children and includes informed assessments based on (mostly physical) health constraints.

However, we also observe variation in individuals’ ratings of their health based on the assessment strategy used, which may be a concern of the question. For example, with regard to time and frequency, assessing the current status and the frequency of health conditions seems to be linked to more positive evaluations of health, while evaluations of severity of health conditions are associated with more negative ratings. Furthermore, good to very good ratings are usually explained with a reference to another person or to oneself in the past, while mediocre ratings are justified without any comparison. Although we cannot tell anything about the direction of this association, it might be that depending on the strategy of evaluating different graduation levels of health and the frame of reference that is used for the assessment, the outcome of the assessment may be systematically different. This could be a problem in analyses of health based on this measure, as this heterogeneity is not reflected in the responses themselves but may influence assignment to specific levels. Therefore, with respect to children and adolescents, we come to the same conclusion as Garbarski et al. (2017), that “results of prior and future studies that use SRH as a measure of health should be interpreted with this complexity and heterogeneity in mind” (p. 10).

In addition to these new insights, we also considered variations in children’s characteristics in order to find out whether the cognitive processes underlying the assessment vary systematically. Although these descriptive results are exploratory and severely limited due to sample size and composition, initial differences by gender, age, migration background, and parental education may have implications for further research. Firstly, we observe some variation by gender. Although we observe a very small sample only, and any identified differences have to be interpreted with caution, boys and girls seem to mention different aspects in their health evaluations. While the girls in our sample were more likely to refer to multiple health dimensions to evaluate their health, boys combined different assessment strategies more often. In addition, boys referred more often to past to present evaluations, based their evaluations more often on severity and frequency of health factors as well as slightly more often employed self-referencing. However, it is unclear whether this led to a different assessment of their health. Boys in our sample more often reported “mediocre” health, they also had a higher proportion of “very good” health. Due to the small sample size, we are unable to show more in-depth analyses on this relationship. Nevertheless, our results provide evidence that boys and girls differ in their assessment of health already at an early stage of life. In light if the still puzzling gender gap in SRH to the disadvantage of girls that is widening in the course of adolescence, these findings are particularly interesting. It might be that systematic gender differences in the evaluation process are at least a part of its explanation. Hence, this matter should be analyzed in more detail in future work.

Secondly, regarding migration and education background, we observe no large differences in children’s answers, which is in support of the validity of the concept, especially for analyses in the field of social and ethnic inequality. However, further studies should address subgroup differences with larger sample sizes and differentiate between countries of origin.

Compared to cognitive interviews in adults, our results indicate both similarities and differences regarding the health dimensions, health factors, and assessment strategies, as well as with regard to group differences. For instance, with regard to the health dimension that children and adults refer to, we observe similarities in children compared to an adults’ study, which highlights that adults do not rate their mental health as frequently as other health dimensions (Garbarski et al., 2017). Our study shows a similar result, although the children in our sample did not consider this dimension of health at all. However, we also observe some major differences regarding the health factors that were mentioned in different studies. While the children in our study named health factors such as temporary illnesses, chronic diseases, health-related behaviors, pain and symptoms, injuries, individual affect, or nonspecific illnesses, adults were shown to consider further aspects, such as health care utilization, aging processes, or external factors (e.g., family background, role as a parent, or available health-related resources) (see Garbarski et al., 2017). In particular, health care utilization seems to be an important factor for adults’ ratings, but it is not the case for the children in our sample. Regarding the assessment strategies, we also observe some differences compared to cognitive interviews with adults: While in previous research, a significant proportion of adult respondents have reported comparisons with others (see Garbarski et al., 2017), only a very small share of children in our sample did so. The majority of the children either referred to their past selves or did not use any reference frame at all.

With respect to group differences, we find conflicting evidence showing some differences by gender that were not found to the same extent among adults. In addition, Garbarski et al. (2017) report differences in health assessments by race and ethnicity among adults, which we did not find to a similar extent. All in all, the similarities in the health domains considered and the health factors mentioned indicate that the measurement of self-rated health seems to work in a similar way in children as in adults; however, differences in the assessment strategies reveal that children rather refer to themselves while taking external factors less into account. If supported in future research, the identified differences between children’s and adults’ cognitive processes have two important implications for research. They challenge the validity of comparisons of SRH across age groups as well as over the life course. Thus, we suggest that future research should explore this matter in much more detail.

Despite various valuable insights, the study has some limitations that leave some questions about children's cognitive processes while evaluating their health status open. First of all, 13 children, a relatively large share of our sample, did not provide a valid answer to our probing question. Note that only one of these children did not provide a score for their self-rated health, while the remaining 12 children were able to provide a rating of their health status and the vast majority of them did not report any difficulties in answering the SRH question, which indicates that SRH can in principle be used in this age group. However, these children were not able to provide a conclusive explanation of their rating and thus, were not included in our analyses, reducing the initial sample size by a quarter. We believe that this large share is at least partly linked to the interview mode that had to be changed to telephone interviews due to the pandemic. Probably, in personal face-to-face interviews, it would have been more feasible to assist children in answering, for instance by asking follow-up questions and finally obtain a valid answer from most of these children. The second drawback refers to the fact that there is only limited variation in the scores of self-rated health. The vast majority of children rated their health “very good” or “good”. Only four children rated their health “mediocre”. Therefore, we cannot analyze any differences in the underlying cognitive processes of the rating depending on the actual health status of the child – or vice versa – in detail with the small sample.

All in all, the study has provided various new insights and setting the course for future research on the cognitive processes of SRH ratings. For practice, this research reveals interesting insights, how children assess their health and which dimensions and factors they consider in their evaluation. It highlights that, if children are asked about their health status, they predominantly think about the physical dimension. Accordingly, in practice, questions about other health aspects may need to be related much more specifically.

Data Availability

Data available on request from the authors due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Notes

The limitations this imposes compared to face-to-face interviews will be discussed in the final section of this study.

Although these answers were less meaningful in terms of content, the probing question was rarely repeated again with these children. In order to keep the children motivated, the interviewers usually accepted their answers and continued with the questionnaire.

In contrast Garbarski et al. (2017), we did not differentiate the valence of health factor used, because this is directly related to the specific health factors mentioned and seemed to be somewhat redundant to this category. Thus, it did not yield any further insights compared to the current coding scheme.

We considered an assessment strategy only if a child used words which directly indicate a specific strategy. We ignored implicit formulations, as this would have induced an excessive degree of self-interpretation on the part of the researchers.

Unfortunately, there is no information on their country of origin available.

The information on the educational level was only assessed for the interviewed parent.

As all children were assigned to exactly one code for the category “reference criterion”, it would have been redundant to include this code into the score.

References

Abdulrahim, S., & El Asmar, K. (2012). Is self-rated health a valid measure to use in social inequities and health research? Evidence from the PAPFAM women’s data in six Arab countries. International Journal for Equity in Health, 11(53), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-53

Als, B. S., Jensen, J. J., & Skov, M. B. (Eds.) (2005). Comparison of think-aloud and constructive interaction in usability testing with children. https://doi.org/10.1145/1109540.1109542

Andreski, P., McGonagle, K., & Schoeni, B. (2009). An analysis of the quality of health data in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Technical Series Paper #09–02. URL: https://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/publications/Papers/tsp/2009-02_Quality_Health_Data_PSID_.pdf [last access: 16.01.2023].

Angel, R., & Gronfein, W. (1988). The use of subjective information in statistical models. American Sociological Review, 53(3), 464–473.

Bircher, J. (2005). Towards a dynamic definition of health and disease. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 8(3), 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-005-0538-y

Blair, J., & Presser, S. (Eds.) (1993). Survey procedures for conducting cognitive interviews to pretest questionnaires: A review of theory and practice. American Statistical Association.

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Roßbach, H.-G. (Hrsg.). (2019). Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). Edition ZfE (2. Auflage). Springer VS.

Boardman, J. D. (2006). Self-rated health among U.S. adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 38(4), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.01.006

Borgers, N., de Leeuw, E., & Hox, J. (2000). Children as respondents in survey research: Cognitive development and response quality 1. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/bulletin De Méthodologie Sociologique, 66(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/075910630006600106

Bradshaw, J., Hoelscher, P., & Richardson, D. (2007). An index of child well-being in the European Union. Social Indicators Research, 80, 133–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9024-z

Bradshaw, J., Martorano, B., Natali, L., & de Neubourg, C. (2013). Children’s subjective well-being in rich countries. Child Indicators Research, 6, 619–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-013-9196-4

Bryant, F. B., & Veroff, J. (1984). Dimensions of subjective mental health in American men and women. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 25(2), 116. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136664

Centre for Longitudinal Studies. (2023). Millennium Cohort Study sweep 6. Young person questionnaire. URL: https://cls.ucl.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/MCS6-Young-Person-Questionnaire.pdf [last access: 16.01.2023).

Chandola, T., & Jenkinson, C. (2000). Validating self-rated health in different ethnic groups. Ethnicity & Health, 5(2), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/713667451

Conrad, F., Blair, J., & Tracy, E. (Eds.) (1999). Verbal reports are data! A theoretical approach to cognitive interviews. Citeseer.

DeMaio, T. J., Rothgeb, J., & Hess, J. (1998). Improving survey quality through pretesting. Washington D.C.

DeMuro, C. J., Lewis, S. A., DiBenedetti, D. B., Price, M. A., & Fehnel, S. E. (2012). Successful implementation of cognitive interviews in special populations. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 12(2), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1586/erp.11.103

Eikemo, T. A., Huijts, T., Bambra, C., McNamara, C., Stornes, P. & Balaj, M. (2016). Social inequalities in health and their determinants: Topline Results from Round 7 of the European Social Survey. ESS Topline Results Series, 6. European Social Survey, London.

Eriksson, I., Undén, A. L., & Elofsson, S. (2001). Self-rated health. Comparisons between three different measures. Results from a population study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30(2), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.2.326

Flick, U. (1998). The social construction of individual and public health: Contributions of social representations theory to a social science of health. Social Science Information, 37(4), 639–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901898037004005

Fosse, N. E., & Haas, S. A. (2009). Validity and stability of self-reported health among adolescents in a longitudinal, nationally representative survey. Pediatrics, 123(3), e496-501.

Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., & Sartorius, N. (2015). Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 14(2), 231–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20231

Garbarski, D. (2016). Research in and prospects for the measurement of health using self-rated health. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(4), 977–997.

Garbarski, D., Dykema, J., Croes, K. D., & Edwards, D. F. (2017). How participants report their health status: Cognitive interviews of self-rated health across race/ethnicity, gender, age, and educational attainment. BMC Public Health, 17(771), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4761-2

Gilman, R., & Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.2.192.21858

Gilman, R., & Huebner, E. S. (2006). Characteristics of adolescents who report very high life satisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9036-7

Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., van der Horst, H., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., Leonard, B., Lorig, K., Loureiro, M. I., van der Meer, Jos W M, Schnabel, P., Smith, R., van Weel, C., & Smid, H. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 343. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4163

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Young, T., Samdal, O., Torsheim, T., Augustson, L., Mathison, F., Aleman-Diaz, A., Molcho, M., Weber, M., & Barnekow, V. (2016). Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health and wellbeing. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report from the 2013/2014 survey. WHO Regional Office Europe, Copenhagen.

Institute for Social and Economic Research. (2023). BHPS Questionnaires and survey documents – Wave 4. URL: https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/bhps/documentation/questionnaires/bhpsw4q.pdf [last access: 16.01.2023].

Joffer, J., Jerdén, L., Öhman, A., & Flacking, R. (2016). Exploring self-rated health among adolescents: a think-aloud study. BMC Public Health, 16(156–166). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2837-z

Jürges, H., Avendano, M., & Mackenbach, J. P. (2008). Are different measures of self-rated health comparable? An assessment in five European countries. European Journal of Epidemiology, 23(12), 773–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-008-9287-6

Klocke, A., Clair, A., & Bradshaw, J. (2013). International variation in child subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research, 2014(7), 1–20.

Krause, N. M., & Jay, G. M. (1994). What do global self-rated health items measure? Medical Care, 32(9), 930–942.

Kroh, J., Gebel, M., & Heineck, G. (2022). Health returns to education across the life course: Measuring health in Children and Adolescents in the National Educational Panel Study. NEPS Survey Paper No. 95. Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories, National Educational Panel Study. https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SP95:1.0

Lee, S. (2014). Chapter Eight: Self-Rated Health in Health Surveys. In T. P. Johnson (Ed.), Health survey methods (pp. 193–216). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118594629.ch8

Lohaus, A., & Ball, J. (2006). Gesundheit und Krankheit aus der Sicht von Kindern. (2., überarb. und erw. Aufl.). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Lundberg, O., & Manderbacka, K. (1996). Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 24(3), 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/140349489602400314

Manor, O., Matthews, S., & Power, C. (2001). Self-rated health and limiting longstanding illness: Inter-relationships with morbidity in early adulthood. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30(3), 600–607. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.3.600

Miller, K., Chepp, V., Willson, S., & Padilla, J. L. (Eds.). (2014). Cognitive interviewing methodology. Wiley.

Miilunpalo, S., Vuori, I., Oja, P., Pasanen, M., & Urponen, H. (1997). Self-rated health status as a health measure: The predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50(5), 517–528.

Poethko-Müller, C., Kuntz, B., Lampert, T., & Neuhauser, H. (2018). Die allgemeine Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland – Querschnittsergebnisse aus KiGGS Welle 2 und Trends. Journal of Health Monitoring, 3(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-004

Pollard, E. L., & Lee, P. (2003). Child well-being. A systematic review of the literature. Social Indicators Research, 61, 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021284215801

Richter, M., & Hurrelmann, K. (2016). Die soziologische Perspektive auf Gesundheit und Krankheit. In Soziologie von Gesundheit und Krankheit (pp. 1–19). Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-11010-9_1

Schnittker, J., & Bacak, V. (2014). The increasing predictive validity of self-rated health. PLoS One, 9(1), e84933. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084933

Wade, D. T., & Halligan, P. W. (2017). The biopsychosocial model of illness: A model whose time has come. Clinical Rehabilitation, 31(8), 995–1004. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517709890

Willis, G. B. (2004). Cognitive interviewing revisited: A useful technique, in theory? In S. Presser, J. M. Rothgeb, M. Couper, & J. T. Lessler (Eds.), Methods for testing and evaluating survey questionnaires (pp. 23–43). Wiley-Interscience. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471654728.ch2

Wilson, I. B., & Cleary, P. D. (1995). Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. JAMA, 273(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03520250075037

Ziebarth, N. (2009). Measurement of health, the sensitivity of the concentration index, and reporting heterogeneity. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research, 211. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1441948

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank collegues of the Leibniz Institute for educational trajectories for their support in conducting this study. We especially thank Andreas Horr and Anika Bela for the supervision in the process. We also thank Nadja Bömmel for her expertise in planning the interviews and Isabella Da Ros, Kevin Glock, Hannes Götz, Alina Happ, Julia Kondrasch, Annelies Maier, Rosanna Purrucker, Carlos Rost, Sabrina Schorr and Lora Todorova for conducting and transcribing the interviews. In addition, we thank the two reviewers and the colleagues of the Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences for their comments and suggestions on the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. Kroh, R. Gentile, and H. Reichelt designed, planned, and conducted the cognitive interviews with the involvement of external interviewers. J. Kroh and J. Tuppat planned and performed the analysis of the qualitative data. J. Kroh and J. Tuppat wrote the manuscript in consultation with R. Gentile and H. Reichelt.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable. All data collection procedures, instruments and documents were checked by the data protection unit of the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi). The necessary steps are taken to protect participants’ confidentiality according to national and international regulations of data security. Participation in the study was voluntary and based on the informed consent of participants.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study or their legal guardians in a written form.