Abstract

This paper presents a cross-national comparison of the influence of parental migration on children’s subjective well-being (SWB). While studies often focus on the economic implications of adult migration, research on its effects on children’s well-being is scarce, particularly in Europe. Data from surveys of over 13,500 school children in six European countries with a communist legacy were analysed. These were collected as part of Children’s Worlds - The International Study of Children’s Well-being (ISCWeB). The findings reveal that left-behind children generally have lower levels of SWB than non-left-behind children, with girls being more affected, and the gap in well-being increases with age. Left-behind status was also associated with lower family and school satisfaction. A hierarchical logistic regression model was used to explore the role of parental migration and family and school life satisfaction in predicting high SWB of children. While including family and school life satisfaction in the model weakened the association between parental migration and child SWB, the models’ explanatory power improved. This study emphasizes the need for further research in this area to better understand the complex dynamics between parental migration, children’s subjective well-being, and other factors. These insights are essential for developing targeted interventions and policies to support the well-being of left-behind children in migrant sending countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Migration is an enduring phenomenon with a historical lineage that spans across centuries. Human populations have traversed geographical boundaries, impelled by a diverse array of catalysts, encompassing both coercive factors prompting individuals to flee their countries of origin, such as armed conflicts and persecution, as well as attractive forces that entice them towards their prospective host nations, such as enhanced economic opportunities and elevated standards of living (Massey et al., 1998; Migali et al., 2018; McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021).

It is estimated that more people today than ever before live outside their country of birth. For example, according to Eurostat (2022), third-country nationals account for 5.3% of the EU population and, in addition, 13.7 million people living in EU Member State are nationals of another EU Member State.

Given its magnitude, migration constitutes a subject of substantial discourse and scholarly investigation across multiple academic disciplines. Predominantly, scholarly inquiries and reports pertaining to international migration tend to emphasize the economic ramifications associated with adult migratory patterns and remittance flows (Inglis et al., 2019). In this way, they are allocating comparatively limited attention to the repercussions experienced by migrant families, particularly regarding children who remain in their home countries (Council of Europe, 2020).

Children who are left behind in their home country while their parents migrate for employment face the potential risk of increased levels of stress, anxiety, and other emotional and psychological challenges (Chipea & Bălţătescu, 2010; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2010; Cortina, 2014; Sun et al., 2015; Antia et al., 2020), although these outcomes are not universally prevalent (Kutsar et al., 2014) and vary between boys and girls (Cortina, 2014; Wu & Cebotari, 2018), and for children of different age (Bălţătescu et al., 2014; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2010). Many studies imply that also their educational results are affected (Wang, 2014; Van Luot et al., 2018; Marchetta & Sim, 2021). Thus, we would expect that all these factors will influence in turn the subjective well-being of children, an indicator of their global appreciation of their lives (Casas & Frønes, 2020).

Consequently, it becomes imperative to intensify our attention and delve deeper into this matter, aiming to comprehend the ramifications it poses for the overall well-being of children residing within transnational families. Of particular interest for us is to test cross-nationally how variables such as gender, age and material deprivation are correlated with the subjective well-being of children left behind, and how satisfaction with school and family life are also independent predictors of this target variable.

In the following, we will review the positive and negative effects of parental migration on children left behind, exploring the impact on their subjective well-being and examining international perspectives. The second chapter will outline the methodology employed, including sample characteristics, measures used, and data analysis techniques. Moving on to the findings, we will compare parental migration patterns across different countries, examine variations in subjective well-being, material deprivation, family and school life satisfaction among children left behind, and explore the associations between parental migration and subjective well-being. Finally, in the discussion and conclusions section, we will interpret the findings, discuss their implications, highlight limitations, and suggest areas for future research.

1.1 Migration of Parents: Positive and Negative Effects on Children Left Home

Migration for work purposes, both internally (nationally) or externally (transnationally), in which one or both parents leave their children at home, has been widely studied, revealing various reasons for the so-called ‘children left behind’ phenomenon. Often, this is due to the lack of documents of children, or sometimes of the whole families in the process of migration (Marcus et al., 2023). Sometimes parents want to avoid exposing their children to racism and discrimination in the destination countries (Ozyegin & Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2008). Work visas often forbid migrants from moving with their families and obtaining visitor visas for kids might be challenging. Additionally, parents’ time and ability to care for their children in the destination country may be limited (UNICEF, 2020). Parents may also be concerned about the safety and educational achievement of their children, or even about the well-being of left alone grandparents. The first pattern of migration is when parents expect reunification in the destination country - although this can take years or could never be realized. A second pattern is when parents expect to come back after a time and may not see the need to move their children to the destination country (Marcus et al., 2023).

As a result, children are often left in the care of a remaining parent (in most cases the mother), a grandparent, aunt, or other relative (Artico, 2003). The care arrangements are dependent on the parent who is abroad: in many cases fathers with children left in care seek help from relatives or friends (Hoang et al., 2015). Estimates of the number of children left behind are rare and rather unreliable. For example, according to the National Authority for Child Protection and Adoption in Romania, the number of children whose parents were away working abroad amounts to approximately 1.9% (ANPDCA Romania, 2023), a magnitude deemed unrealistically low by the NGOs working in the field. Much higher levels are estimated in Philippines and Kyrgyzstan (27%, respectively 10% with at least one parent leaving abroad) (UNICEF, 2020). As per investigations documented in a compendium on women’s migration in Europe, between 60 and 100% of the women interviewed by different contributors in destination countries had left their children behind (Lutz, 2008). The policy responses to this phenomenon range from completely ignoring it to recognizing that children are being deprived of fundamental protection, care, and assistance. The rapporteur for the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe concludes in an official document that “leaving millions of children without parental care is a mass violation of human rights” (Council of Europe, 2020).

The effects of parental migration on children can usually be divided into two categories: positive and negative. The better access to resources that the migrant family has is typically linked to favourable outcomes, resulting in more money for the family through remittances, which can relieve financial pressure on family members in the home nation or region. The income effect can enable greater investments in healthcare and education and open new options for business investment (Démurger, 2015). Thus, children of emigrants have improved financial conditions and gain higher status than their non-emigrant classmates.

While a family’s financial capital may vary, it also gains from the social capital built through social networks during the move process. We are dealing with a culture of migration, which has turned into a significant source of social capital, which transfers from parents to children, claims Dreby (2007) regarding migration from Mexico to the United States.

Some studies in Asia focus on the positive relationship that migration of parents has with the resilience of children. Despite absence of one or two parents, their school performance and school enjoyment are not affected, at least if their mothers are not absent for longer times (Jampaklay & Vapattanawong, 2013; Jordan & Graham, 2012). These findings are consistent with certain results showing that in terms of child schooling (Yang, 2008), academic performance (Botezat & Pfeiffer, 2014), and even academic aspirations (Shen & Zhang, 2018), the benefits of migration (mostly by fathers) appear to outweigh the disadvantages of parental absence.

The line of demarcation between positive and negative effects crosses mostly the field of education. Additional research that examined the detrimental effects of parental absence discovered that parental migration reduces school enrolment (Wang, 2014), increases the likelihood of a child dropping out of school (Marchetta & Sim, 2021), and has a negative effect on their objective (Song et al., 2018) and subjective (Van Luot et al., 2018) academic achievement.

Some of the most important negative effects are also those related to health. Overall, children who were left behind had considerably worse health-related quality of life than other children (Racaite et al., 2019). Physical health problems such as infectious disease, underweight, anaemia or overweight have been found to be present in equal measure or even less frequent in a meta-analysis on conditions of children left behind (Fellmeth et al., 2018). Both this literature review and a second one (Antia et al., 2020) revealed, however, that these children face an increased risk of developing mental health problems such as depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, conduct disorders, suicidal ideation, and substance use. Children feel abandoned and rejected, exhibiting symptoms of losing a loved one. This is why in the literature the psychological effects are considered like those of parent’s divorce, and as Cortina (2014, pp. 3–4) observes, children display “higher levels of externalizing behaviours (disruptive, hyperactive and aggressive behaviours) and internalizing problems (withdrawn, anxious, inhibited and depressed behaviours)”.

Assessing the causal relationship between being left alone and many of these conditions raises endogeneity problems. This is primarily due to the omission of variables that are related to both the decision to migrate and the experiences of family members who remain behind (Démurger, 2015). For example, in the case of severe couple disagreements, the decision to migrate of one parent masks the imminent dissolution of the family. Moreover, the relationship between migration and child well-being outcomes is dynamic and dependent on a variety of factors, making it difficult to clearly categorize potential effects on child well-being as positive or negative (Gassmann et al., 2018).

However, it is worth noting that all the effects attributed to children being left behind are linked to their subjective well-being, which will be further explored in the next section of this paper.

1.2 Subjective Wellbeing of Children Left Behind

1.2.1 Concept and Usefulness

Subjective well-being is the extent to which a person has a favourable assessment of the overall quality of his/her life (Veenhoven, 1984). This assessment is made by the individual, with cognitive (satisfaction with life) or affective (positive and negative affect) devices. Diener (1984) highlights that it is subjective in the sense that it depends on the individual’s experience, it comprises a broad evaluation rather than just a focused evaluation of one area of life, and it encompasses both positive actions and the lack of harmful ones.

While, based on these theoretical bases, the literature on adult subjective well-being exploded since the 1980’s, the traditional approach to child well-being remained focused on objective indicators such as mortality rates, malnutrition, immunization rates, disease rates, etc. and the happiness of children and adolescents is still regarded as unimportant (Casas, 2011). However, since the beginning of 21st century, remarkable progresses in this area have been made by recognizing the children’s subjective perspectives, accepting them as a unit of observation and systematically gathering children’s data (Ben-Arieh, 2008).

Thus, research on the subjective well-being of children left behind is very useful. Cortina (2014) stresses the need for a deeper understanding of key assumptions to analyse the effects of migration on those left behind, such as whether remittances boost life satisfaction. Subjective indicators, he argues, are used in conjunction with other well-being statistics, but excluding subjective variables from well-being assessments may skew policymakers’ assumptions, an approach that Allardt (1993, p. 93) would name “the undue dogmatism resulting from the use of objective indicators only”. This is also a way to overcome the critique that the negative effects of parental migration are overestimated, giving the propensity of the studies to focus exclusively on the emotional effects while ignoring the significance of the economic factors or those linked with personal development, social adjustment, or resilience (Cojocaru et al., 2015). The influence of most of these factors, even those that are difficult to measure, is summarized by the subjective well-being of children, which reflects their evaluation of the objective conditions of their lives.

1.2.2 Comparative Levels

Most studies conclude that being left behind is detrimental to children’s subjective well-being. Using data from a survey in Romania, within a random sample of 1811 high school students grades 10–12, Bălţătescu (2008) found that having both parents abroad is correlated with life satisfaction, when controlling for grade, gender, material endowment, father’s education, parental control, and satisfaction with school. Results are confirmed on a Romanian national representative sample survey of 10 to 13 years-old students (n = 2868): children with the lowest SWB are those with both parents abroad, and the effect of mother going abroad is almost as detrimental as having both parents abroad (Bălţătescu et al., 2014). This is linked with gender roles, conclude Kutsar et al. (2014) when, using a projective technique, found that children in Estonia displayed stereotypical attitudes towards gender labour division. When asked to describe the emotions involved with being left behind, 72% of children in the same sample said that such children would feel sad and 58% that they would feel unhappy. Graham et al. (2012) also found that children with migrant parents are unhappier, while Cortina (2014) discovered that life satisfaction (measured using the BMSLSS scale - Seligson et al., 2003) of children with at least one migrant parent from Quito and Tirana is significantly lower than that of those who live with both parents.

A series of papers investigates the life satisfaction of left behind children in rural China. Su et al. (2013) found that children with two parents migrating reported the lowest level of satisfaction. In a longitudinal study in the same province, being left alone at the time of the first wave was found to decrease life satisfaction and happiness of children reported in the second wave, which took place after six months (Su et al., 2017). Self-reported happiness in the previous year was also found to be lower in rural Chinese children (Fan & Fan, 2021). According to a study conducted in another Chinese region, the life satisfaction of left-behind children is lower, which the authors attributed to the absence of parental care (Song et al., 2018). Shen and Zhang (2018) also found that children from both-parent migrant families report much lower levels of happiness and confidence in the future than children co-residing with both parents. They name the migration “a double edge sword”, giving that children’s aspirations to attend college are increased by father-only migration, even more so than the positive effects of parental education and family income. Comparative research in China and Ghana yielded the same results for both countries (Wu & Cebotari, 2018). A single study in rural China failed to detect any statistically significant differences in positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction between left-behind and non-left behind children (Ye et al., 2020); however, the authors admit that compared to other categories of parental migration status, children whose mothers were migrants had the most significantly lower SWB scores.

Various factors moderate the relationship between the left-behind status of children and their subjective well-being. Among the demographic variables, the focus was on the gender, age, and material resources of the family.

1.2.3 Gender

The gender effect was negative for girls in rural China, Wu and Cebotari (2018) observing that they consistently reported lower levels of life satisfaction than their peers in non-migrant households without a migration history, irrespective of their own migration experiences, which may be linked to the subordinate status of girls in Chinese families. Cortina (2014) identified a deficit in the same direction in Tirana, but in opposite direction in Quito. Meanwhile, another study in China found “marginally significant gender differences” (Song et al., 2018). While the evidence is barely conclusive, it seems that girls are more emotionally affected by the leave of their parents, thus leading to depression (Robila, 2011). Children feel insecure because of the lack of parent availability when needed. Moreover, parents do not inform them about the duration of their absence. Thus, they lack confidence in the stability of the family (Kutsar et al., 2014). Those in the rural areas may also be affected by an increased household workload (Song et al., 2018).

1.2.4 Age

Bălţătescu et al. (2014) found that the relationship between left-behind status and subjective well-being is weaker for 12–13 years old compared to 10–11 years old, which would be explained by a process of adaptation of children to their situation (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2010). Cortina (2014, p. 9) also estimates that the gap in satisfaction between left behind children and the rest of the children seems to reduce with age. Older children may be less affected emotionally because they enjoy, among others, more independent decision-making and spend more time with friends than younger children (Kutsar et al., 2014).

1.2.5 Material Goods

Jordan and Graham (2012) found “no direct evidence of a moderating relation between social and migration status”, with respect to resilience (which they measure as life satisfaction and enjoyment of school). Similarly, Bălțătescu et al. (2014) found a very weak path between being left behind, satisfaction with material situation of the family and subjective well-being. Cortina (2014), while acknowledging the importance of remittances on objective well-being indicators such as access to education, health and food, found that the children’s satisfaction with their lives is not statistically impacted by remittance-related spending for food, toys, health care, or education, either combined or separately. This concords with the conclusions of his qualitative study that “even though families, children and adolescents left behind may benefit from remittances, these funds do not compensate for the absence of the father, mother or both” (p. 10).

1.2.6 Family

When children are left behind and their relationships with primary caregivers (either parents or relatives) are strong and trusting, they may be able to cope with the difficulties brought on by extended parent-child separation and meet their basic psychological needs, which will increase their subjective well-being (Chai et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2022). In China and Ghana, children who interacted with their migrant parents frequently reported higher levels of life satisfaction and self-esteem, as well as decreased loneliness and sadness (Sun et al., 2015). Higher life satisfaction was also linked to stronger parental support in Romania (Robila, 2011), China, and Ghana (Wu & Cebotari, 2018). However, higher monitoring from parents was found to rather decrease life satisfaction (Robila, 2011; Wu & Cebotari, 2018). Family satisfaction serves as an indicator that encompasses these sometimes-contradictory influences. It is generally lower for children left behind by migrant parents (Bălţătescu et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2020). In a path model both parents being abroad influence satisfaction with life negatively directly, but also through satisfaction with family life and with the school marks. The effect is significantly weaker in sixth graders compared to fourth graders (Bălţătescu et al., 2014).

1.2.7 School

The school effects of being left alone were typically assessed through more objectively oriented indicators, such as school performance and dropout rates. Nevertheless, there are also reports of its impact on students’ school satisfaction. Jordan and Graham (2012) found that school enjoyment in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam was not affected. Similarly, results in urban China showed that students who stayed behind displayed similar levels of academic satisfaction to those whose parents did not migrate (Lan & Moscardino, 2019). In contrast, a longitudinal study conducted by Su et al. (2017) in rural China revealed that, after controlling for important demographic factors and parental migration characteristics in the previous survey wave (six months before), being left behind was associated with lower levels of satisfaction with schooling.

1.3 International Perspectives

A considerable number of studies examining the well-being of children left behind originate from countries with significant immigration patterns situated in Central and South America, as well as in Asia. Such research is less common in Europe’s newest countries of immigration. However, the new member nations of the European Union have seen a major rise in labour migration, particularly since the EU’s expansion (Kutsar et al., 2014). In this part, we will provide a concise overview of the research findings, statistics, and policies pertaining to each of the six countries included in our study. All these countries participated in the third wave of the Children’s Worlds Study (ISCWeB) and shared a common legacy of communist rule until the late 1980s and early 1990s. Following the collapse of communism, primarily due to economic circumstances, emigration from these countries experienced a substantial surge. This trend has persisted over the past two decades, as evidenced by data from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) (Table 1). The highest levels are found in Albania (with an increase from 20.9% in 2000 to 30.3% in 2020), Croatia (from 17% to 20.2%), and Romania (from 4.9% to 17.2%). The countries with the lowest percentual migration stock among the six included in our study are Hungary (from 4% to 6.9%), Poland (from 5% to 11.3%) and Estonia (from 9.2% to 13.5%). For reference, in Europe (excluding Russia), the share of migrant stock increased from 6.3% to 8% in the comparable period.

1.3.1 Albania

Since the fall of the communism in 1991, Albania has experienced one of the highest relative population exoduses, and was called „a laboratory for the study of migration” (King, 2005). Political instability, economic, demographic, and cultural causes contributed to the increase in the number of people who left the country. Lack of perspective and problems related to children’s education were also important factors (Gëdeshi & King, 2018). According to measurements of the ratio between migrants and the population, Albania has experienced the highest wave of immigration in all of Europe (Government of Albania, 2018). 829,200 Albanian citizens were registered in 2020 with valid residence permits in EU countries (Eurostat, 2023). Giannelli and Mangiavacchi (2010), who studied the long-term effects on the schooling of children whose parents were out of the country during their development, drew attention to the psychological implications of this situation. Moreover, the responsibilities that children assume within the family reduce the time allocated to education, thus leading to an increase in the school dropout rate, especially in the case of girls.

The public policy recommendations regarding the improvement of the situation aim at economic changes, which contribute to increasing the well-being of the population, but also measures that facilitate the return to the country of those who have left (Gëdeshi & King, 2018; Government of Albania, 2018).

1.3.2 Croatia

In 2021, 40,424 people migrated out of Croatia, the top destination countries being Germany (32.1%), Bosnia and Herzegovina (16.2%), Serbia (9.8%), Austria (8.4%), and Kosovo (4.2%). The most significant number of people who migrated abroad were aged between 20 and 39 years old. Croatia’s entry into the European Union marked a turning point in this phenomenon, with Germany and Austria becoming preferred destinations for Croatian migrants. The main push factors are the decline in living standards, fall of overall employment rates, difficulty to find a permanent job in the profession, and a general dissatisfaction with the country, and the perception of an uncertain future in Croatia. Germany has lifted restrictions on the free movement of labour and provided services geared to Croatian citizens. Remittances amounted to 5,044,681.50 USD in 2021, representing 7.3% of Croatia’s GDP (Integral Human Development, 2023). Despite the high level of migration, the studies on children left behind are rare, and mostly linked with the problem of forced migration caused by the Balkan war circumstances (1992–1993). A study conducted in Zagreb schools comparing the academic performance of migrant children revealed that those with parents living abroad face greater educational challenges, even if they remained in the same school and environment, compared to their peers who did not have migrant parents and had no experience with migration (IMIN, 2021).

1.3.3 Estonia

Working abroad is more widespread among the population of Estonia than is the average for Europe. Estonia’s accession to the European Union in 2004 has significantly influenced emigration from this country, due to disappearance of borders and the opening of the employment markets of other societies. However, work migration experienced a significant surge following the onset of the economic crisis in 2008. During this period, over two thousand Estonian residents sought employment and better income abroad, positioning Estonia as one of the prominent countries of origin for migrant workers in Europe (Krusell, 2015; Nerb et al., 2009). According to the Estonian Labour Force Survey, the share of employed people in Estonia whose main job was abroad was the highest in 2010–2012 (around 7%) and then slowly decreased, remaining at 3% by 2021 (Statistics Estonia, 2022). Men and younger middle-aged people dominated among the migrant workers (Krusell, 2009). The data from European Social Survey conducted in 2021 indicates that people with underaged children are more likely to have worked abroad in the last ten years than people who do not have minors (authors’ calculation). Most often the job emigrants are fathers, while mothers stay with children in the homeland. For years by now, the main destination of the migration by job for men has been Finland because of higher salary level there compared to Estonia, its geographical closeness, language similarity and job vacancies in the construction sector.

1.3.4 Hungary

Based on the European Social Survey in 2021, 5.6% of Hungarians had worked in another country for more than 6 months during the last ten years (authors’ calculation). According to a recent survey, about 40% of Hungarians agreed that the main reason for people wanting to move abroad were the low salaries (Republikon Intézet, 2022). However, about a third agreed that the state of democracy in the country was also a significant reason behind emigration. Their primary destinations were other EU member states. In 2022, 26,500 Hungarian citizens emigrated, most often to Austria, Germany and the UK. Among them, about 15 thousand were men and 11 thousand were women (Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2023). Similar to Estonia, in Hungary, fathers tend to migrate for work more frequently than mothers. Additionally, job-related migration has a greater impact on children from two-parent families compared to those living in single-parent households. Approximately 22 thousand children are potentially affected by the consequences of parental migration (Blaskó & Szabó, 2016).

1.3.5 Poland

The migration of Poles is not a new phenomenon. The country has a long history of economic and political emigration, dating back to the 19th century and linked to changes in Polish statehood. The last major wave of emigration took place at the end of the first decade of the 21st century and was linked to Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2004. The opening up of many European labour markets, combined with Poland’s high (youth) unemployment rate at the time, resulted in many Poles finding employment in Western and Northern Europe (Matyjas, 2017).

The Statistics Poland (GUS) recorded more than 300,000 documented cases of permanent emigration to European countries between 2004 and 2020. At the same time, by the end of 2020, around 2,239 thousand permanent residents of Poland temporarily stayed outside the country (Statistics Poland, 2021). Currently, according to estimates made by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), over 4.8 million Poles live abroad, which is more than 11% of the total population of the country. This means that Poland has the largest (next to Romania and the UK) emigrant population in Europe (McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021).

Such a scale of the migration phenomenon in Poland puts it in the spotlight of the media, state institutions, and researchers. Attempts are being made to assess the consequences of foreign migration in demographic, economic, and social terms both at the macro and the micro level (Puzio-Wacławik, 2010; Zieniuk-Cupryn, 2016). Many studies and reports are devoted to migrant families and especially to children raised in such families (Dąbrowska & Szumilas, 2017; Danilewicz, 2012; Ostrowska, 2017; Walczak, 2008, 2014). Children whose one or two parents have gone abroad for work are often referred to in the literature as Euro-orphans (Brągiel, 2013). This term, although it highlights the negative socio-educational consequences of parental migration, is pejorative and stigmatizing. Not every migrant family can be considered dysfunctional, and the impact of this phenomenon on child development and well-being is more complex (Gizicka, 2010).

1.3.6 Romania

Romania is one of the countries with a long history of migration, especially in the last 60 years. Most changes occurred after 1989, when the nature of migration changed. If during Communism there were few categories of the population that made such a decision, now anyone who wanted had the freedom to take this step (Horváth & Anghel, 2009). Thus, more and more people chose to leave the country, the economic situation and the social, administrative, education and health problems being the most important contributors to the immigration decision. When in 2007 Romania entered European Union, the improvement of migrants’ rights in European destination countries accelerated the process. As a result, Romania, along with the Russian Federation, Ukraine, and Poland, was listed among the Eastern European countries with the largest populations of emigrants in the region. In 2020, Romania ranked 14th among the world top 20 countries of origin for migrants, with 3.98 million citizens abroad representing 17.1% of the total population (McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021).

Since 2006, the issue of children left behind has gained public attention due to alarming cases highlighted by the media, depicting instances of severe abuse and neglect experienced by vulnerable children under the care of entrusted adults. Particularly distressing were incidents involving child suicides. In response to these concerns, legislation was enacted requiring parents migrating abroad to disclose their circumstances to local councils. Moreover, a monitoring mechanism was established in collaboration with local social work services, with the National Authority for Child Protection periodically reporting relevant statistics. Several qualitative and quantitative studies were carried out (Irimescu & Lupu, 2006; Chipea & Iacob, 2010; Toth et al., 2007) and textbooks for intervention were designed (Cojocaru et al., 2006; Luca et al., 2009). However official figures are obviously underestimated, mainly because few parents declared their departure abroad, while the social work institutions were found not to be sufficiently involved in prevention of dysfunctional effects on children (see for a review of all these topics Chipea and Bălţătescu, 2010).

The aim of the present paper is a cross-national comparison of the influence of parental migration on children’s subjective well-being in six European countries with a communist legacy and a history of migration after 1990s: Albania, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Poland and Romania. It seeks finding answers to the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the comparative levels of subjective well-being (SWB) of children left behind (LBC) in these countries?

-

2.

How gender, age and material deprivation affect the subjective well-being of children left behind?

-

3.

How the migration of parents is correlated with the satisfaction with school and family life and how these variables predict, when controlling for demographics, the subjective well-being of children left behind?

2 Methods

2.1 Sample Characteristics

This study draws upon data from the six above-mentioned post-communist countries collected during the third wave of The Children’s Worlds: International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCWeb), an innovative worldwide research endeavour that seeks to gather reliable and inclusive information about the lives and everyday experiences of children. The study focuses on various aspects, such as children’s routines, time allocation, and most importantly, their personal perspectives and assessments of their own well-being in diverse cultural contexts. The current research is based on data from the third and largest wave of data collection, which was conducted between 2016 and 2019 in 40 countries from five continents. The survey was based on self-completed questionnaires asking children in mainstream schools about their feelings and satisfaction with various aspects of their lives. The study was conducted by national research teams with the ethical approval from the relevant committee (Rees et al., 2020). To ensure the representativeness of the survey in each country (or specific region), appropriate individual sampling strategies were developed and approved by an international team of experts.

Items on parental migration, which were essential to the analysis of the current study, were included in the questionnaires of over 20 countries. However, the sample of countries in the present study was limited to six countries: Albania, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. These societies, distributed in Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe, have communist legacies. After the fall of communism, all these countries have undergone significant transitional changes, resulting in higher levels of unemployment and economic uncertainty, which have contributed to increased levels of emigration. Joining European Union (in 2004 and 2007) offered their citizens (apart from those in Albania) legal access to the job market, thus increasing even more the number of those migrating.

The initial sample of the study included 13,589 children aged 10 and 12 years from these six countries. Owing to a lack of information on parental migration, 387 (2.8%) children were not included in the current study. The final sample consisted of 13,203 children, with sample sizes per country ranging from 2,001 children in Hungary to 2,350 children in Romania. The description of the sample is presented in Table 2.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Parental Migration

Two questions were used to identify the children from migrant families. The children were asked whether their mother (1) or father (2) had lived or worked abroad for more than one month in the past year.

Considering the pooled sample, almost 4% of the respondents reported that their mothers had gone to work in another country in the last 12 months. The experience of separation from the father was more common, affecting more than 16% of children. The two rates do not add up because some children experienced both parents going abroad for work (simultaneously or alternately). Thus, 18.2% of children experienced separation from at least one parent. The distribution of children who experienced parental migration in each country is shown in Table 3 and discussed in Sect. 3.1.

2.2.2 Subjective Well-being

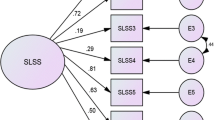

The Children’s Worlds Subjective Well-Being Scale (CW-SWBS) was used to explore the children SWB. This measure was designed based on the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (Huebner, 1991) to improve the cross-cultural comparability of the results of the third wave of the Children’s Worlds study. This context-free psychometric scale was based on five statements about children’s overall well-being: “I enjoy my life”, “My life is going well”, “I have a good life”, “The things that happen in my life are excellent”, “I am happy with my life” and is the most recommended SWB scale for cross-country comparative studies (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2021).

The children aged 10 and 12 responded to the questions using an 11-point scale ranging from “Not at all agree” to “Totally agree”. The internal consistency of the CW-SWBS measured with Cronbach’s α, was 0.934 for the pooled sample and ranged, depending on the country, from 0.816 for Albania to 0.945 for Estonia. The five items were summed, and following the recommendations of the ISCWeB, the sum was multiplied by 2 to create a scale from 0 to 100. A higher value of the CW-SWBS indicates a greater level of well-being.

2.2.3 Material Deprivation

Children’s family material deprivation was measured through a set of eight questions about their access to or possession of items such as, for example, clothes and shoes in good condition, enough money for school trips, internet at home, equipment for sports and hobbies, pocket money, or a mobile phone. The material deprivation index, based on the approach proposed by Main and Bradshaw (2012), was calculated by adding up the number of items that children lacked from zero to eight.

2.2.4 Family Life and School Life Satisfaction

Children’s family-related satisfaction was measured with the question “How satisfied are you with the people you live with?”, whereas their school life satisfaction was based on the question “How satisfied are you with your life as a student?”. Both questions were on an 11-point satisfaction scale ranging from “Not at all satisfied to “Totally satisfied”.

2.3 Data Analysis

The first part of the analysis presents descriptive statistics on children’s general life assessment (CW-SWBS), parental migration, material deprivation, and satisfaction with family and school. Due to the non-normal distribution of the independent variable, the relationships between the CW-SWBS and the independent variables were examined in more detail using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. For the same reason, hierarchical logistic regressions were then performed to predict subjective well-being separately for each country. Since the mean scores of the CW-SWBS were strongly biased towards positive values, the index had been dichotomized. Previous approaches using Children’s Worlds data recommended that at least a 75 − 25 ratio to be used for determining cut-off points (Rees, 2019). In our case, we chose those children scoring 80 or more points (out of 100) to be classified into the group with high well-being. In the first step, parental migration, family material deprivation, and age group and gender as dummy variables were entered in the models. Then, satisfaction with family members and satisfaction with life as a student were added to find out the persistence of the effects of parental migration.

3 Findings

3.1 A Comparison of Parental Migration, by Country

Table 3 shows the structure of children who experienced separation from their parents for each of the countries analysed. In two countries - Croatia and Hungary - less than 12% of children reported that at least one of their parents had recently left abroad to work, while in Romania and Albania, such children were 27.8% and 23.3%, respectively. Fathers’ migration prevailed in all six countries. The share of children indicating that only their fathers had migrated for work ranged from 19.9% in Albania to 9.9% in Hungary. In Albania, on the other hand, fathers accounted for the largest share (96%) of all migrating parents. The highest proportion of children with experience of only maternal migration was observed in Romania (4.8%), and this was more than four times higher than, for example, in Poland and Estonia. Romania also had the highest number of children who experienced migration from both parents.

3.2 Variations in SWB, Material Deprivation, Family and School Life Satisfaction

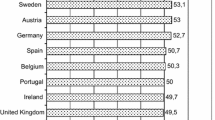

Table 4 presents the differences between countries in terms of children’s subjective well-being. Children from Albania and Romania had the highest mean scores on the CW-SWBS scale. Some 92–96% of children from these countries rated their overall well-being at a high level. At the opposite end of the spectrum in this aspect were countries such as Estonia and Poland, where less than 75% of children evaluated their lives very positively.

The highest scores for family life satisfaction were observed in Albania, Romania, and Croatia (see Table 5). The same three countries stood out in terms of the highest level of school life satisfaction. It is worth emphasizing that, in all surveyed countries, the average scores of children’s satisfaction with the people they lived with were higher than the average level of satisfaction with their life as a student. The child-derived index of material deprivation ranged from 0.25 in Hungary to 0.83 in Albania.

3.3 Bivariate Associations Between Parental Migration and Overall SWB of a Child

The first research question of this study was whether having migrant parents is a depressing factor in a child’s subjective well-being. As can be seen in Table 6, in all the countries analysed, children who indicated that at least one of their parents had migrated abroad were characterised by lower average levels of SWB compared to non-migrant children, although, except for Albania and Croatia, the differences were not statistically significant.

Furthermore, in all countries, particularly low levels of subjective well-being were experienced by children with at least a migrant mother. This particularly strong relationship between child SWB and separation from the mother was primarily experienced by children in Estonia. There were no significant differences in Hungary and Poland, but this is obviously because of the small size of subsamples with such children, given that in these countries only 1.2–1.5% of the children were in this situation.

Taking into consideration the gender of the child, the study shows that separation from parents due to migration is mostly severe for girls (Table 7). In four countries (Albania, Estonia, Poland and Romania), girls who indicated that at least one of their parents worked abroad experienced much lower levels on the CW-SWBS scale than did those whose parents did not. Among boys, these differences were only noticeable in Poland and Romania.

The impact of parental migration on subjective well-being was stronger among 12 years-old-children. At the same time, significant differences were not found between 10-year-olds with migrant parents and those with non-migrant parents, except for Estonia (Table 7).

In contrast, in Croatia and Hungary, the countries with the least frequent instances of parental migration, no significant differences in average levels of subjective well-being (SWB) were observed between children from migrant and non-migrant families in various subgroups categorized by gender and age.

3.4 Bivariate Associations Between Parental Migration, Material Deprivation, Family Life and School Life Satisfaction

The next stage of the analysis assessed the relationship between parental migration and three other independent variables: family material deprivation, children’s satisfaction with family life, and student life. Bivariate comparisons are summarised in Table 8.

Evidence across most countries supports the notion that there is a relationship between children’s satisfaction with family life, specifically the individuals they reside with, and their experiences of parental separation. In most countries (excluding Croatia), children who were left behind exhibited lower levels of satisfaction than their counterparts. However, statistically significant differences were observed solely in Albania, Estonia, and Romania.

Similar differences were observed regarding children’s satisfaction with their life as a student. Children whose at least one parent had gone abroad to work reported significantly lower levels of satisfaction in half of the countries. This pattern was particularly visible in Poland.

Similarly, family material deprivation among children of migrants was found to be higher than that of non-left-behind children in all six analysed countries. However, the statistical tests revealed significant differences only in Estonia and Romania.

3.5 Regression Models with Parental Migration, Material Conditions and Family and School Satisfaction as Predictors of Children’s SWB

Next, hierarchical regression analyses were performed to investigate how parental migration, together with other independent variables, could predict high subjective well-being. Table 9 presents the regression coefficients and odds ratios for each country. In Models A, age, gender, material deprivation, and parental migration accounted for 7% (Nagelkerke R2 for Hungary) to 15% (for Albania) of the variance in subjective well-being. The Models B, including additionally the satisfaction estimates of family and school, indicated a noticeable improvement, particularly for Estonia and Croatia, where the R-squared values increased the most. The analysis revealed that in both Models A and B, in all countries included in the study, children who scored high on the index of material deprivation were more likely to evaluate their subjective well-being as low. With regard to parental migration, the Models A showed statistically significant effects only for Estonia, Poland, and Romania, referring to lower SWB among children whose one or both parents had stayed abroad for at least a month in the last year. After adding family and school satisfaction to the models, parental migration remained a significant determinant for Poland and Romania.

The results in Models B indicated that domain-specific satisfaction assessments significantly predicted overall subjective well-being in all observed countries, except for Albania. In other words, children who rated their satisfaction with family members and school higher were more likely to belong to the group with high subjective well-being than were those whose ratings of family and school were lower. For Albania, only school satisfaction was positively related to the assessments of life in general.

In accordance with the findings of previous studies (e.g. Casas and González-Carrasco, 2019), overall life satisfaction declined with age similarly across countries. Gender also turned out to be a statistically significant factor in most models, but not in the same way for all countries. In Croatia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania, boys reported higher satisfaction with their lives, while in Albania, girls did (only in Model A); in the case of Estonia, this relationship was insignificant.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

This study aims to cross-nationally compare the influence of parental migration on children’s subjective well-being in six European countries with a communist legacy and migration history after the 1990s: Albania, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. It focuses on the following research topics: comparative levels of subjective well-being (SWB) among children left behind (CLB) in these countries; the relationship between parental migration and children’s satisfaction with family life and overall life; impact of parental migration on girls’ and boys’ SWB; how children of migrating parents assess the family’s material situation; the effect of parental migration on children’s satisfaction with school; independent influences of these factors on children’s subjective well-being in these countries.

The six European countries included in the research exhibit a complex situation concerning both the prevalence of children left behind and migration strategies adopted by parents residing abroad. The proportion of children who experienced temporary separation from their parents was more than twice as high in Albania and Romania than in Croatia and Hungary. Furthermore, the research findings indicate a notable gender disparity in the decision to migrate among the surveyed countries. Specifically, fathers were found to be significantly more inclined (up to eight times) than mothers to choose migration. Several factors, including gendered occupational segregation, societal expectations of men as providers, lack of job opportunities for women in some industries, concerns about safety and security, and caregiving roles and responsibilities placed on women within families, are mentioned among the explanations (Christou & Kofman, 2022). However, Romania stood out, with an average percentage of migrating mothers almost three times higher than that in other countries. Migration of mothers was conceptualized as “care drain” (Ehrenreich & Hochschild, 2003). It is not exceptional that at such levels, the critical situation of children left behind became most visible in Romania.

Our research provides evidence of the important role of parental migration in children’s global assessment of their own lives. In general, the results are consistent with those of various studies (Bălţătescu, 2008; Cortina, 2014) indicating that experiencing separation from parents due to their departure abroad is a significant factor in lowering a child’s SWB, although the strength of the impact varies from country to country. Comparing, for instance, the two countries with the highest share of children from migrant families, while in Romania the differences between the SWB of children not left behind and the SWB of children from all categories of left behind (at least father, at least mother or at least one parent) are statistically significant, in Albania the difference is significant only for not left- behind children and children who have or had at least the mother abroad (Table 6). One possible reason is that transnational families vary greatly in these six countries in what concerns the family structure, the social relationships, norms and the distribution of gender roles within the family, as well as the motives, timing and duration of migration. However, as shown in Table 4, in all countries the children who are in at least one of these three categories have lower SWB than the not left-behind children, so the key message is that migration of a parent does reduce the subjective well-being of children.

Overall, we are inclined to conclude that, taken into account context differences, the parental migration is negatively associated with children’s satisfaction with family and with school life, while there are some context differences. In three of the countries analysed, children of migrant parents show significantly lower levels of satisfaction with their family members, which seems to support previous results (Bălţătescu et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2020). Similarly, satisfaction with school life was strongly correlated with parental migration in half of the countries analysed, demonstrating that coming from a transnational family can, under certain conditions, negatively affect a child’s perception of himself as a student. On one side this calls for the need for more in-depth analyses targeting, for example, the quality of relationships in transnational families or the frequency of contact with the absent parent, or the quality of relationships that children have at school with peers and teachers. On the other hand, we cannot interpret correlation as causation. There may be other factors involved (e.g., deterioration of the relationship between parents) that may contribute both to the decision to migrate and to low family satisfaction.

This evidence may be related to higher vulnerability of children whose parent(s) are on the move because of, for example, the lack of permanent availability of the parent when the child is in need, and not feeling safe about the future. Kutsar et al. (2014) showed that children felt unconfident about their future because the parents had not informed them about the motivation of the migration or the time of the return. Thus, children left behind by migrating parents are left facing alone their home and school problems, including coping with school bullying or solving stressful situations at home. Moreover, they may not be informed how long this vulnerable situation will last. In the same way, the burden of increased care tasks at home may be the main cause of lower subjective well-being of children left behind, mostly in the case of girls.

Indeed, our study shows that girls are more vulnerable than boys to the negative consequences of having migrant parents. In four of the six countries analysed, girls whose at least one parent went abroad for some time stood out with significantly lower levels of SWB, while such significant differences among boys were only found in Poland and Romania. Satisfaction with family life was also significantly lower among left-behind compared to non-left behind girls in most countries: in Albania, Estonia, Poland and Romania. No such differences were observed among the boys. We agree with Robila (2011), who suggested that girls, compared to boys, are more emotionally affected by the leave of their parents especially in cases of mother’s job migration. Jordan and Graham (2012), and also Ye et al. (2020), admit that mothers’ migration endangers most significantly the SWB of their children. Romanian children are at the highest risk, giving the high levels of mothers’ emigration from this country. Results by Kutsar et al. (2014) suggest that parent’s job migration impacts traditional family roles, particularly for migrating fathers, who are often freed from their children’s emotional care, as previously pointed out by Dreby (2006). By contrast, migrant mothers face difficulties due to their crucial role in providing emotional care. The absence of mothers affects their availability to children and their ability to meet their customary needs. Parent(s) job migration leads to changes in both the relational and structural aspects of family life. Others must assume the responsibilities of departed family members. These changing roles, along with a shift in responsibilities and care, result in reduced children’s subjective well-being (SWB) and satisfaction with family life.

One of the most consistent results of this study is that the difference between left-behind and non-left-behind children seems to widen with age (Table 7). This rather contradicts the previous findings (Bălţătescu et al., 2014; Cortina, 2014). On one hand, older children adapted better to their circumstances. Moreover, they may be less emotionally impacted since they have more independent decision-making power and spend more time with friends, among other factors, compared to younger children. However, they may need to care for their younger siblings, particularly when their mother migrates (or help their mother when their father is away). The opposing influences of these factors need to be further explored.

The study also indicated that children with migrant parents experience greater material deprivation, which is associated with lower overall subjective well-being (Models A and B). This is consistent with previous research showing that migration does not increase the level of living of the family above the average levels (Cortina, 2014; Jordan & Graham, 2012). According to one of the most influential theories in the field, the decision to migrate is based on the relative deprivation of household members (Stark & Taylor, 1989). Parents migrate by job to improve their families’ economic performance, but this cannot bring about a momentous change in the family’s or the child’s life.

An important message of this paper is that while left-behind children tended to have lower levels of SWB, in the six Central and Eastern European countries, there is no uniform picture of the negative impact of parental migration once other analysed variables are included. For example, considering the material deprivation of a child’s family, significant differences in subjective well-being between non-left-behind and left-behind children were found only in three countries: Estonia, Poland, and Romania. Thus, material deprivation is associated with children having lower SWB, but it does not necessarily eliminate the link between living in a migrant family and the child’s perception of life. The introduction of family and school life satisfaction into the logistic regression models (compare Models A and B for each country in Table 7) substantially weakened the association between parental migration and child SWB only in Estonia. In this country, the differences in SWB between children from migrant and non-migrant families are no longer statistically significant once family life satisfaction is considered. In other countries, the new variables slightly weakened the correlations between parental migration and child SWB, although the explanatory power of the models it improved. Thus, the analyses suggest that there may be some moderating factors for the relationships between status of being left behind, satisfaction with family and school, and subjective well-being. Further research is needed in this area.

4.1 Limitations and Further Work

Despite the unique nature of the study, there are some limitations that need to be mentioned. First, the design of the study is cross-sectional. As always with correlational analysis any influences or causal relations mentioned in the text are only suggested and cannot be proved. Second, the analysis is based on children’s answers to a question mixing their parents’ labour migration with departure for other reasons. In addition, as the children only indicated whether their parents had spent at least one month abroad in the past year, we were not able to investigate how long they had experienced separation from their mother and/or father and how long ago this situation had occurred. At the same time, it is not clear whether children who declared the international migration of both parents experienced an episode of their absence simultaneously or alternately. Finally, this study did not focus on the relationship and frequency of contact between the children and their parents residing/working abroad. All these considerations may be important factors in explaining the impact of parental migration on children’s SWB.

Further research effort should also be dedicated to the independent effect of the family structure and of the care arrangements for the children left behind (giving that, for example, living in the multi-generational households may buffer the effect of the absent parent(s)). All these factors should be tested independently using mediation/moderation analysis techniques. Additional studies may address also the situation of younger children (Children’s Worlds study also focus on 8 years old children), potentially the most vulnerable to the negative consequences of parental absence.

All these conclusions and limitations highlight the importance of conducting further research in this field to gain a deeper understanding of the intricate interactions between parental migration, the subjective well-being of children left behind, and the factors that moderate or mediate these relationships. Obtaining these insights is crucial for formulating more specific and effective interventions and policies that can help improve the well-being of left-behind children in countries that send out migrant workers. With a greater understanding of the factors that influence the well-being of these children, policymakers and practitioners will be better equipped to implement targeted strategies to address the unique challenges faced by this vulnerable population.

Data Availability

Data is freely available from the Project website (https://isciweb.org/).

Code Availability

Not aplicable.

References

Allardt, E. (1993). Having, loving, being: An alternative to the swedish model of Welfare Research. In M. Nussbaum, & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 88–94). Oxford University Press.

ANPDCA Romania (2023). Situaţie copii cu părinţi plecaţi la muncă în străinătate [Situation of children with parents working abroad] 30.09.2022 Autoritatea Naţională pentru Protecţia Drepturilor Copilului și Adopție [National Authority for the Protection of the Rights of the Child and Adoption]. https://copii.gov.ro/1/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Situatie-copii-cu-parinti-plecati-la-munca-30-09-2022.doc.

Antia, K., Boucsein, J., Deckert, A., Dambach, P., Račaitė, J., Šurkienė, G., Jaenisch, T., Horstick, O., & Winkler, V. (2020). Effects of International Labour Migration on the Mental Health and well-being of left-behind children: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4335. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124335.

Artico, C. I. (2003). Latino families broken by immigration: the adolescent’s perceptions. LFB Scholarly Publ. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/fy037/2003003569.html.

Bălţătescu, S. (2008). June 6–7). Migration of a parent, well-being and social competence of adolescents. A study with Romanian high school students International workshop: The Effects of International Labor Migration on Political Learning, Cluj-Napoca. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4409213.

Bălţătescu, S., Hatos, A., & Oșvat, C. (2014). September 15–18). The effects of parental migration on subjective well-being of children: the case of Romania Sustaining Quality of Life across the Globe. The XII Quality of Life Conference, Free University Berlin. http://www.isciweb.org/_Uploads/dbsAttachedFiles/BerlinISQOLSEffectsParentalMigration_Baltatescu.pdf.

Ben-Arieh, A. (2008). The child indicators Movement: Past, Present, and Future. Child Indicators Research, 1(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-007-9003-1.

Blaskó, Z., & Szabó, L. (2016). Migrants with left-behind children in Hungary. In K. Fazekas, & Z. Blasko (Eds.), The hungarian labour market 2016 (the hungarian labour market yearbooks) (pp. 87–89). Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323014698_Migrants_with_left-behind_children_in_Hungary.

Botezat, A., & Pfeiffer, F. (2014). The Impact of Parents Migration on The Well-Being of Children Left Behind: Initial Evidence from Romania. http://ftp.iza.org/dp8225.pdf.

Brągiel, J. (2013). „Eurosieroctwo” jako rezultat przemiany więzi rodzinnych [Euro-orphanhood as a sign of the transformation of family bonds]. Family Forum, 3, 155–169. https://czasopisma.uni.opole.pl/index.php/ff/article/view/893.

Casas, F. (2011). Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indicators Research, 4(4), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-010-9093-z.

Casas, F., & Frønes, I. (2020). From snapshots to complex continuity: Making sense of the multifaceted concept of child well-being. Childhood, 27(2), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568219895809.

Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2019). Subjective well-being decreasing with age: New Research on Children over 8. Child Development, 90(2), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13133.

Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2021). Analysing comparability of four Multi-Item Well-being psychometric Scales among 35 countries using children’s worlds 3rd Wave 10 and 12-year-olds samples. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1829–1861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09825-0.

Chai, X., Li, X., Ye, Z., Li, Y., & Lin, D. (2019). Subjective well-being among left-behind children in rural China: The role of ecological assets and individual strength. Child: care health and development, 45(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12630.

Chipea, F., & Bălţătescu, S. (2010). Copiii lăsaţi acasă de emigranţi. Studiu în judeţul Bihor [Children left home by emigrants. A study in Bihor County]. Sociologie românească VIII(4), 104–126. https://arsociologie.ro/revistasociologieromaneasca/sr/article/view/2010_4_chipea/285.

Chipea, F., & Iacob, A. (2010). Impactul migraţiei părinţilor asupra „copiilor rămaşi acasă”. Studiu exploratoriu la nivelul judeţului Bihor [The impact of parents’ migration on “children left at home”. Exploratory study at the level of Bihor county]. In S. Bălţătescu, F. Chipea, I. Cioară, A. Hatos, & S. Săveanu (Eds.), Educaţie şi schimbare socială. Perspective sociologice şi comunicaţionale (pp. 159–166). Editura Universităţii din Oradea.

Christou, A., & Kofman, E. (2022). Gender and Migration: An Introduction. In A. Christou & E. Kofman (Eds.), Gender and Migration (pp. 1–12). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91971-9_1.

Cojocaru, M., Gulei, A., Irimescu, G., Luca, C., Lupu, A., & Miftode, V. (2006). Migraţia si traficul minorilor neînsoţiţi: măsuri urgente pentru minorii aflaţi in situaţie de vulnerabilitate extremă [Migration and trafficking of unaccompanied minors: Urgent measures for minors in a situation of extreme vulnerability]. Course support within the project “Irregular Migration and Traffiking in unaccompanied minors. Urgent Measures for Minors in Situations of Extreme Vulnerability”.

Cojocaru, S., Islam, M., & Timofte, D. (2015). The effects of parent migration on the children left at home: the use of ad-hoc research for raising moral panic in Romania and the Republic of Moldova. Anthropologist, 22(3), 568–575.

Cortina, J. (2014). Beyond the money: The impact of international migration on children’s life satisfaction: Evidence from Ecuador and Albania. Migration and Development, 3(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2014.885635.

Council of Europe (2020). Impact of labour migration on left-behind children. https://pace.coe.int/en/files/28741/html.

Dąbrowska, A., & Szumilas, E. M. (2017). Uczniowie z rodzin migracyjnych w szkole [Pupils from migrant families in school]. Ośrodek Rozwoju Edukacji.

Danilewicz, W. (2012). Rodzina w wyobrażeniach pedagogów i jej rzeczywistych doświadczeniach [The perception of family as by educators and its real experiences]. Rocznik Lubuski, 38(2), 117–127.

Démurger, S. (2015). Migration and families left behind. IZA World of Labor. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.144.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

Dreby, J. (2006). Honor and Virtue: Mexican parenting in the transnational context. Gender & Society, 20(1), 32–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205282660.

Dreby, J. (2007). Children and power in Mexican transnational families. Journal of Marriage and Family,69(4), 1050–1064. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00430.x

Ehrenreich, B., & Hochschild, A. R. (2003). Global woman: Nannies, maids, and sex workers in the new economy. Macmillan.

Eurostat (2023, April 18). Enlargement countries - statistics on migration, residence permits, citizenship and asylum. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Enlargement_countries_-_statistics_on_migration,_residence_permits,_citizenship_and_asylum&oldid=485831.

Eurostat (2022, March 30). Non-EU citizens make up 5.3% of the EU population. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20220330-2.

Fan, Z., & Fan, X. (2021). Effect of Social Support on the Psychological Adjustment of Chinese left-behind Rural Children: A Moderated Mediation Model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 604397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.604397.

Fellmeth, G., Rose-Clarke, K., Zhao, C., Busert, L. K., Zheng, Y., Massazza, A., Sonmez, H., Eder, B., Blewitt, A., Lertgrai, W., Orcutt, M., Ricci, K., Mohamed-Ahmed, O., Burns, R., Knipe, D., Hargreaves, S., Hesketh, T., Opondo, C., & Devakumar, D. (2018). Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 392(10164), 2567–2582. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32558-3.

Gao, C., Tadesse, E., & Khalid, S. (2022). Word of Mouth from Left-Behind children in Rural China: Exploring their psychological, academic and physical well-being during COVID-19. Child Indicators Research, 15(5), 1719–1740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09923-7.

Gassmann, F., Siegel, M., Vanore, M., & Waidler, J. (2018). Unpacking the relationship between parental Migration and Child Well-Being: Evidence from Moldova and Georgia. Child Indicators Research, 11(2), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9461-z.

Gëdeshi, I., & King, R. (2018). New trends in potential migration from Albania. Tirana: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Office.

Giannelli, G. C., & Mangiavacchi, L. (2010). Children’s Schooling and Parental Migration: Empirical Evidence on the ‘Left-behind’ Generation in Albania. LABOUR, 24, 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9914.2010.00504.x.

Gizicka, D. (2010). Dzieci w Polsce a skutki migracji zarobkowych rodziców [Children in Poland and the effects of their parents’ job migration]. Studia Polonijne(31), 159–169.

Government of Albania (2018). The National Strategy of Diaspora and Action Plan 2018–2024. Retrieved from: https://diaspora.gov.al/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/NATIONAL-STRATEGY-OF-DIASPORA-2018-2024-english-IOM.pdf.

Graham, E., Jordan, L. P., Yeoh, B. S. A., Lam, T., Asis, M., & Su, K. (2012). Transnational families and the Family Nexus: Perspectives of indonesian and filipino children left behind by migrant parent(s). Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(4), 793–815. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4445.

Hoang, L. A., Lam, T., Yeoh, B. S. A., & Graham, E. (2015). Transnational migration, changing care arrangements and left-behind children’s responses in South-east Asia. Children’s Geographies, 13(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2015.972653.

Horváth, I., & Anghel, R. G. (2009). Migration and its consequences for Romania. Comparative Southeast European Studies, 57(4), 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2009-570406.

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the student’s life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 12(3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034391123010.

Hungarian Central Statistical Office (2023). 22.1.1.31. A kivándorló magyar állampolgárok célországok és nemek szerint [Emigrating Hungarian citizens by destination, country and gender]. https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/nep/hu/nep0031.html.

IMIN (2021). Croatian Children in Migration and Return (Completed projects). https://www.imin.hr/en/croatian-children-in-migration-and-return-5-12-090.

Inglis, C., Li, W., & Khadria, B. (2019). The SAGE handbook of international migration. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Integral Human Development (2023). Country Profile: Croatia. https://migrants-refugees.va/country-profile/country-profile-croatia.

Irimescu, G., & Lupu, A. (2006). Home alone! Study made in Iași area on children separated from one or both parents due to parents leaving for work abroad]. Asociaţia Alternative Sociale. http://www.childrenleftbehind.eu/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/2006_AAS_CLB_Romania.pdf.

Jampaklay, A., & Vapattanawong, P. (2013). The Subjective Well-Being of children in transnational and non-migrant households: Evidence from Thailand. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 22(3), 377–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719681302200304.

Jordan, L. P., & Graham, E. (2012). Resilience and well-being among children of migrant parents in South‐East Asia. Child Development, 83(5), 1672–1688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01810.x.

King, R. (2005). Albania as a laboratory for the study of migration and development. Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans, 7(2), 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613190500132880.

Krusell, S. (2009). Eesti residentide välismaal töötamine [Estonian residents working abroad]. Eesti statistika kvartalikiri, 2(9), 46–62.

Krusell, S. (2015). Estonians Working Abroad. In E. Saar (Ed.), Estonian human development report 2014/2015 (pp. 124–131). Estonian Cooperation Assembly.

Kutsar, D., Darmody, M., & Lahesoo, L. (2014). Borders Separating Families: Children’s Perspectives of Labour Migration in Estonia. In S. Spyrou & M. Christou (Eds.), Children and Borders (pp. 261–275). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137326317_15.

Lan, X., & Moscardino, U. (2019). Direct and interactive effects of perceived teacher-student relationship and grit on student wellbeing among stay-behind early adolescents in urban China. Learning and Individual Differences, 69, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.12.003.

Luca, C., Pascaru, G., & Foca, L. (2009). Manual pentru profesioniştii care lucrează cu copiii rămaşi singuri acasă ca urmare a plecării părinţilor la muncă în străinătate. Terra Nostra. http://singuracasa.ro/_images/img_asistenta_sociala/top_menu/Colaboraretransfrontaliera/Pachet%20de%20resurse/manual.pdf.

Lutz, H. (2008). Migration and domestic work: a European perspective on a global theme. Ashgate. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0720/2007023686.html.

Main, G., & Bradshaw, J. (2012). A child material Deprivation Index. Child Indicators Research, 5(3), 503–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-012-9145-7.

Marchetta, F., & Sim, S. (2021). The effect of parental migration on the schooling of children left behind in rural Cambodia. World Development, 146, 105593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105593.

Marcus, R., León-Himmelstine, C., Carvalho, T., & Rodríguez, D. J. T. (2023). Children who stay behind in Latin America and the Caribbean while parents migrate. UNICEF LACRO. https://www.unicef.org/lac/media/40976/file/children-who-stay-behind.pdf.

Massey, D., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. (1998). Worlds in motion. Understanding International Migration at the end of the millennium. Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

Matyjas, B. (2017). Social and educational impact of euro-orphanhood (based on the research conducted among primary school students). Wychowanie w Rodzinie XV(1), 39–52. https://www.repozytorium.uni.wroc.pl/dlibra/show-content/publication/95981/edition/89958/.

McAuliffe, M., & Triandafyllidou, A. (Eds.). (2021). World Migration Report 2022. International Organization for Migration (IOM). https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022.

Migali, S., Natale, F., Tintori, G., Kalantaryan, S., Grubanov-Boskovic, S., Scipioni, M., Farinosi, F., Cattaneo, C., Benandi, B., Follador, M., Bidoglio, G., McMahon, S., & Barbas, T. (2018). International Migration Drivers. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC112622.

Nerb, G., Hitzelsberger, F., Woidich, A., Pommer, S., Hemmer, S., & Heczko, P. (2009). Scientific report on the mobility of cross-border workers within the EU-27/EEA/EFTA countries.

Ostrowska, K. (2017). O sytuacji dzieci, których rodzice wyjechali za granicę w celach zarobkowych. Raport 2016 [On the situation of children whose parents have gone abroad for work. Report 2016]. Ośrodek Rozwoju Edukacji.

Ozyegin, G., & Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (2008). Conclusion: Domestic Work, Migration and the New Gender Order in Contemporary Europe. In H. Lutz (Ed.), Migration and domestic work: a European perspective on a global theme (pp. 195–208). Ashgate. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315595306.

Puzio-Wacławik, B. (2010). The Social and Economic Impact of the Migration of Poles after Poland’s accession to the EU. Zeszyty Naukowe PTE, 8, 179–193.

Racaite, J., Surkiene, G., Jakubauskiene, M., Sketerskiene, R., & Wulkau, L. (2019). Parent emigration and physical health of children left behind: Systematic review of the literature. European Journal of Public Health, 29(Supplement_4), https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz186.024.

Rees, G. (2019). Variations in children’s Affective Subjective Well-Being at seven Years Old: An analysis of current and historical factors. Child Indicators Research, 12(1), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9516-1.

Rees, G., Savahl, S., Lee, B., & Casas, F. (2020). Children’s views on their lives and well-being in 35 countries: A report on the Children’s Worlds study, 2016-19. https://isciweb.org/the-data/wave-3/wave-3-comparative-report/.