Abstract

Wellbeing has recently been given a more prominent place in education policy and discourse, with critics arguing that an overemphasis on achievement comes at the cost of well-being. This raises questions concerning possible trade-offs between the traditionally dominant focus on learning and achievement in education and the growing emphasis on well-being. Can education systems promote high achievements and wellbeing simultaneously, or is reduced wellbeing an inevitable price to pay for high academic achievements? In this study, I investigate possible trade-offs between country-level achievement and individual wellbeing using five waves of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) data, spanning over 18 years and including more than one million pupils in 45 countries. I find weak and inconsistent empirical support for a trade-off. While there is a modest negative relationship between country-level achievement and some indicators of well-being, this does not hold when adjusting for possible confounders or country-fixed effects. I also find no or weak evidence for heterogeneous effects depending on individual achievement. I conclude that concerns regarding possible trade-offs between achievement and wellbeing are not supported by cross-country comparative data. However, the predominantly null findings also imply that policymakers should not expect miracles in terms of wellbeing from high-achieving education systems. High achievements may be good from an academic perspective, but do not seem to make much of a difference from the perspective of wellbeing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Growing opportunities to compare the performance of education systems through international large-scale assessments has intensified the traditionally dominant achievement discourse in education, with calls for higher standards, more testing, intensified competition, and stronger accountability (Grek, 2009). However, the narrow focus on achievement has also been challenged by a growing wellbeing discourse (Ecclestone & Hayes, 2008; Layard & Hagell, 2015; Park & Chung, 2014) emphasizing that achievement must not come at the cost of the socio-emotional development of children in schools.

These conflicting discourses raise questions regarding possible trade-off between achievement and wellbeing in education: can education systems promote high achievements and wellbeing simultaneously, or is reduced wellbeing an inevitable price to pay for high academic achievements? The question of trade-offs has recently figured prominently in research (Clarke, 2020; Ling et al., 2022; Lv & Lv, 2021; Montt & Borgonovi, 2018; Rudolf & Lee, 2023) and policy reports (Layard & Hagell, 2015; UNICEF, 2009) alike. On the one hand, proponents of the necessity of a trade-off argues that “effective learning is often not enjoyable” (Heller-Sahlgren, 2018a: vi) and that de-emphasizing the centrality of achievement means that pupils are deprived of “meaningful challenges” and “important educational experiences” (Mintz, 2012: 250). On the other hand, prominent international organizations such as the United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) posit that achievement and wellbeing not only should go together in education systems (UNICEF, 2009), but that they can even be “self-reinforcing goals” (OECD, 2017: 79).

Existing research on the relationship between academic achievement and wellbeing at the level of countries and education systems is scarce (Montt & Borgonovi, 2018; OECD, 2017; Wang, 2016), and it is not known to what extent the relationship is conditional on the type of wellbeing considered (Clarke, 2020), if it holds over time while accounting for stable characteristics of countries (OECD, 2017), and if it differs across pupils with different characteristics, such as between high- and low-achieving pupils. Against this background, the aim of this study is to investigate the interrelationships between country-level achievement and individual-level wellbeing. Specifically, I address two research questions:

Is country-level achievement on average related with individual-level wellbeing (RQ1)?

Does country-level achievement moderate the relationship between individual-level achievement and wellbeing (RQ2)?

To this end, I use five waves of harmonized survey data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study, spanning over 18 years and including more than one million pupils. The study makes four main contributions to the existing literature on achievement and wellbeing. First, the use of a broad range of wellbeing indicators – pertaining to domain-specific, emotional and evaluative wellbeing – provides a more multifaceted picture of the achievement-wellbeing relationship. Second, since the data are longitudinal at the level of countries, I can hold stable country characteristics constant, and investigate if changes in achievement over time is related to changes in wellbeing, thus improving on causal inference (Woessmann, 2016). Third, by combining country-level data on achievement and individual-level data on both achievement and wellbeing, I can investigate heterogeneous effects depending on individual achievement, and thus whether the potential costs of emphasizing achievement will disproportionally be borne by low- or high-achieving pupils. Fourth, the paper provides the first systematic theoretical elaboration of the possible mechanisms linking country-level achievement with wellbeing, thereby contributing to a clearer understanding of the nature of possible achievement-wellbeing trade-offs.

Understanding possible trade-offs between achievement and wellbeing in education is important for several reasons. Education has multiple goals – we typically want pupils to learn the academic content, but also to thrive and develop as individuals, and to be prepared for future challenges in life such as the transition to work. How these goals relate to each other influences the notion of what education is and should be. This in turn is important from the perspective of policy as well as for stakeholders. If the responsibility of education systems extends beyond transferring academic content, policymakers need to know the consequences of education policies for non-academic outcomes. Moreover, to the extent that a strong emphasis on achievement has negative side effects on wellbeing, policymakers should find ways to counter these through compensatory measures such as investing in school nursing and counselling. Likewise, although this study is focused on the macro-level, understanding possible trade-offs is in a broader sense also important for pupils and their parents, whose optimal mix of achievement and wellbeing may vary as a function of how these goals relate to each other empirically (Rudolf & Bethmann, 2022; Rudolf & Lee, 2023). Pupils who disproportionately value wellbeing may regard lower achievement as acceptable, and conversely, pupils who disproportionately value achievement may be willing to sacrifice wellbeing. In addition, understanding possible trade-offs may elucidate the role of education and achievement pressures for the deteriorating wellbeing among adolescents observed in recent years (Sweeting et al., 2010).

2 Research Background

2.1 The Concept of a Trade-off Between Achievement and Wellbeing

What does it mean to speak of an achievement-wellbeing trade-off in education? The relationship between country-level achievement and individual wellbeing can be viewed as purely associational, but the notion of a trade-off implies a causal relationship, concerning whether or not education systems can promote achievement and wellbeing simultaneously. However, the treatment or exposure in this study – country-level achievement – cannot be viewed as an intervention in the strict sense of the word, where the researcher can, at least hypothetically, manipulate the treatment in order to study how this affects the outcome (Holland, 1986). The idea of a trade-off does not mean that higher achievement in itself generates low wellbeing; the core of the idea is that the mechanisms within education systems that leads to higher achievement also leads to lower wellbeing. Hence, the treatment can be seen a proxy for a bundle of more specific policies and practices related to education systems, such as specific teaching strategies or academic climates. This implies that the meaning of the research question, and the aim of the empirical analysis, is to investigate how education systems that promote achievement – net of basic social, economic and demographic differences that are largely outside the influence of education systems (Woessmann, 2016) – shape pupils’ wellbeing. Thus, the study is primarily focused on education systems as a whole, not on the myriad of specific policies or practices that on a more concrete level constitute education systems. It should be noted that a directionality of the causal relationship is implied by the discourse of a trade-off: it is higher achievement, or policies that emphasise achievement, that is postulated to harm wellbeing, not the other way around. That higher wellbeing would reduce achievement, albeit possible, is seldom considered (e.g. Clarke, 2020; UNICEF, 2009).

2.2 Previous Research on the achievement-wellbeing Trade-off

Research on the relationship between achievement and wellbeing at the individual level does not support the notion of a trade-off. Most research have found the relationship to be positive, though usually moderate in size, and often bidirectional (Amholt et al., 2020; Bücker et al., 2018; Kaya & Erdem, 2021). The, admittedly scarce, existing country-level evidence paints a different picture. Using PISA data, Montt and Borgonovi (2018) found that no country managed to efficiently promote both mathematics achievement and wellbeing simultaneously. Wang (2016) found a positive cross-country correlation between mathematics achievement and suicide rates among teenagers. Official PISA reports have found relatively weak negative cross-country correlations between science and reading achievement, on the one hand, and life satisfaction on the other (OECD, 2017, 2019). However, as stated by PISA (2017: 74), the cross-sectional data used in these studies means that the correlations “should not be interpreted as evidence of a trade-off between high achievement and student wellbeing. The results might, in fact, partly reflect cultural differences in response styles and self-presentation”. In sum, the research to date does not allow for firm conclusions regarding possible trade-offs.

2.3 The case Against a Trade-off, or the case for a win-win Relationship

As stated, most individual-level research have found a “win-win” (i.e. positive) relationship between achievement and wellbeing (Amholt et al., 2020; Bücker et al., 2018; Kaya & Erdem, 2021). A positive and bidirectional relationship is also posited by the dominant psychological theories in the field. For instance, self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) posits that feeling competent is essential for wellbeing, and that achieving academically can fulfill this need. Broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001), in turn, posits that wellbeing (positive emotions) broadens pupils’ thought-action repertoires and motivates them to explore and create, which in turn fosters learning. Moreover, developmental cascades theory posits that academic failure undermines motivation and self-esteem, thus generating mental health problems. In turn, low motivation and mental health problems also undermines academic achievement, leading to a self-reinforcing negative spiral (Moilanen et al., 2010).

To the extent that the individual-level relationships described by these studies can be aggregated to the level of countries, we would expect a positive relationship between country-level achievement and individual wellbeing through a simple composition effect: since high-achieving pupils feel better, higher achievement on average will result in more pupils who feel well.

An additional but less common argument against a trade-off is that policies that most efficiently foster achievement also foster wellbeing. For instance, according to self-determination theory and progressivist ideas, teaching strategies that encourage intrinsic motivation improves both achievement and wellbeing, while controlling strategies that use external incentives such as rewards or punishments have the opposite effects (Mintz, 2012; Ryan & Weinstein, 2009; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006). Note that this argument does not rely on aggregating individual-level relationships, as the treatment – teaching strategies – is already a contextual-level factor that may operate at the level of countries.

2.4 The case for a Trade-off

Sociological theories of stratification suggest that an aggregation of individual-level relationships of the kind underlying the case against a trade-off is not warranted, and that the conclusions of this literature cannot be translated to the level of countries. In contemporary knowledge societies, academic achievements (e.g. credentials) are the key instrument used to allocate individuals to locations in the labour market, especially to high-status occupations (Collins, 1979; Domina et al., 2017; Hirsch, 1978). The main value of credentials thus lies in their exchange value in the labour market, that is, in how they can be exchanged for jobs and income. Moreover, academic credentials, especially at higher levels, are rationed, and access to these are typically regulated by previous achievements such as grades. Thus, the main value of academic achievements at lower educational stages lies in their exchange value within the education system, that is, in how they can be exchanged for access to specific schools, programmes or degrees at higher levels (Collins, 1979). Since status is by definition relative, and the demand for both higher-status occupations and credentials exceed the supply, the value of academic achievements is inherently relative as well.

A large literature has documented that pupils to a large extent study because of the exchange value of academic achievements, and that this is also the main reason for why achievement is consistently rated as among the most prominent stressors in their lives (Denscombe, 2000; Luthar et al., 2013; Stentiford et al., 2021). Since the exchange value of achievements is relative, pupils are primarily concerned with their achievements relative to the achievements of their peers. However, virtually all aforementioned studies investigating the relationship between achievement and wellbeing at the individual level have been conducted in single countries, meaning that the measure of achievement have been identical with relative achievement (i.e. relative to other pupils in the same country). In other words, it is not possible to infer from these studies that average achievement and wellbeing will rise in tandem through simple aggregation, since pupils’ relative achievements will by definition remain the same regardless of the average achievement.

The view of achievements as positional and hence relative suggests a possible mechanism for the existence of a trade-off: negative externalities. If the supply of higher-status jobs or credentials is fixed and does not keep up with demand, competition becomes a zero sum game, and each pupil’s achievement exerts a negative externality (i.e. cost) on all others’ (cf. Ramey and Ramey, 2009; Rudolf and Bethmann, 2022). This is because, if one pupil raises his or her achievement, other pupils must either increase their efforts in order to keep up, or face the prospect of a devaluation of the exchange value of their present achievement.

The negative externality here comes in the form of “effort”, but there are reasons to expect that negative externalities may extend to wellbeing as well. First, high achievement can require substantial investments in terms of hard work and emotional engagement. This has opportunity costs, as the time and energy devoted to studying cannot be used for other activities that pupils may find more pleasurable (Lv & Lv, 2021; Rudolf & Bethmann, 2022). The empirical basis for this mechanism is mixed, however, with studies showing that, while pupils experience lower wellbeing when they study than during leisure activities, pupils who study long hours do not necessarily have lower wellbeing overall (Csikszentmihalyi & Hunter, 2003; Lee & Larson, 2000; OECD, 2017). Second, high achieving contexts are often characterized by intense performance cultures and competitive climates (Luthar et al., 2013; Stentiford et al., 2021). In such contexts, intimate and supporting bonds are replaced by rivalry (Luthar et al., 2013), which in turn breeds anxiety and undermines wellbeing (Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Rudolf & Lee, 2023). Third, high-achieving contexts are often characterized by a disproportionate valuation of academic achievements, in turn coupled with a strong belief in meritocratic ideals (Lee & Larson, 2000; Luthar et al., 2013). In addition to their direct exchange value within the education system, academic achievements thereby takes on a broader cultural meaning, signifying success and personal worth. This raises the stakes involved even higher, with academic failure becoming a threat to one’s identity and sense of self-worth (Denscombe, 2000).

An additional argument for a trade-off, one that does not rely on the presence of negative externalities, is that policies that most efficiently foster achievement may not be conducive to wellbeing. For instance, teacher-directed instruction and frequent and/or high-stakes testing is often found to be effective at promoting learning (Hattie, 2008; Woessmann, 2016), but may simultaneously be experienced as tedious or stressful by pupils (Högberg & Horn, 2023; Jürges & Schneider, 2010).

2.5 Interrelation Between Country-level and Individual Achievement

Previous research and theory offer scant guidance concerning whether and how the importance, in terms of wellbeing, of country-level achievement varies with individual achievement (RQ2). However, ad hoc arguments can be can be made for why both low- and high-performing pupils will be disproportionately affected by the achievements of their peers.

On the one hand, it can be expected that low-achieving pupils will struggle more to keep up with a high average achievement. In high-achieving contexts, the curriculum may be more demanding (Lee & Larson, 2000), forcing low-achieving pupils to exert disproportionate effort to avoid falling behind. To the extent that they, despite great effort, fail to keep up, this may harm their self-esteem and self-worth (Ryan & Weinstein, 2009). Likewise, to the extent that country-level achievement and the cultural valuation of achievements are interrelated, low-achieving pupils may experience more stigma and shame in high-achieving countries, as academic achievement is then more indicative of personal worth and status.

On the other hand, the negative externality-hypothesis is arguably most valid at the higher end of the achievement distribution. High individual achievement tends to go hand in hand with high aspirations, meaning that the competition for access to later educational stages is most intense among high-achievers (Luthar et al., 2013). If so, the stress and anxiety caused by a strong pressure to succeed academically may be most pronounced among high-achievers. Self-determination (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and developmental cascades (Moilanen et al., 2010) theory generate similar predictions: higher country-level achievement mechanically implies fewer pupils who fail academically (e.g. fewer dropouts), in which case more pupils will feel competent and motivated, which in turn fosters wellbeing.

3 Data and Methods

3.1 PISA data

Survey data from PISA have four advantages given the aim of this study. First, a wide range of participating countries enables comparison of different education systems. Second, multiple survey waves allow for adjustment for stable country characteristics using country fixed effects. Third, among international large-scale assessments, PISA includes the broadest set of indicators related to wellbeing. Fourth, the hierarchical structure, with pupils nested in countries, allows for investigation of how country-level achievement moderates individual level relationships.

PISA is an international study aimed at measuring skills in reading, science and mathematics among 15-year-old pupils. It has been repeated every three years since 2000, with the latest survey conducted in 2018. PISA uses a two-stage survey design: schools are selected with probability proportional to their number of pupils in the first stage, and 35–42 eligible pupils per school are selected with equal probability in the second stage. The sample is designed to be representative of the total population of eligible pupils in the respective country (see the PISA Technical Reports for more information on the study design (OECD, 2018).

For this analysis, I include all participating countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and/or European Union (EU) (see complete list in Supplementary file A). In addition to these, I also include Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao and mainland China. This is because East Asian countries – with very high scores in international assessments – figure prominently in discussions concerning trade-offs between achievement and wellbeing (Lee & Larson, 2000; Ling et al., 2022; Montt & Borgonovi, 2018; Park & Chung, 2014). I exclude middle-income countries as participation rates in formal education among 15-year olds are often well below 100%, in which case the PISA sample will be skewed. I include all survey waves with data on wellbeing: 2000, 2003, 2012, 2015 and 2018. The estimation samples vary across models depending on data availability, and ranges from 45 countries and around 1,100,000 pupils when pooling all waves to 31–38 countries and around 200,000 pupils when analyzing the 2018 wave. I weigh observations such that each country contributes equally to the analyses.

3.1.1 Outcome Variables in PISA: Wellbeing

I include three indicators of wellbeing. Positive and negative affect captures affective wellbeing, and is measured with a set of items drawn from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (Ebesutani et al., 2012). High negative affect is related with both anxiety and depression, while low positive affect is specifically related to depression. In PISA, pupils are asked how often they feel “happy”, “lively”, “proud”, “joyful”, and “cheerful” (positive affect) or “scared”, “miserable”, “afraid” or “sad” (negative affect). Response options are “never”, “rarely“, “sometimes“ and “always“. Cronbach’s alpha are 0.763 (negative affect) and 0.823 (positive affect), respectively.

School belonging captures domain-specific wellbeing related to school, and is measured using the PISA index of sense of belonging to school. Pupils are given six statements of the type “I feel like an outsider (or left out of things) at school.” Response options include “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”. After reverse-coding three items, higher values indicate greater belonging. Cronbach’s alpha varies from 0.770 to 2000 to 0.844 in 2015.

While identical items on school belonging have been included in five PISA waves (2000, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018), positive and negative affect were only included in the 2018 survey. I therefore use two different analytical samples when analyzing PISA data: a full sample (waves 2000, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018) when analyzing school belonging, and the 2018 wave for the other outcomes. I follow the guidelines of PISA (OECD, 2018); Ebesutani et al., (2012), and use generalized partial credit models to construct the indices of school belonging and positive and negative affect. All outcome variables are standardized (mean = 0; standard deviation = 1) in order to facilitate comparison of effect sizes.

3.1.2 Treatment Variables in PISA: Achievement

PISA measures achievement in mathematics, reading and science. I use mathematics achievement in the main analysis, as mathematics arguably is most difficult to learn outside of formal education, and hence is most indicative of the input from the education system. Country-level achievement is generated by calculating the average achievement in mathematics in each country and wave. In order to capture relative achievement, individual achievement is measured as each pupil’s deviation from the relevant country-wave average achievement. Both individual and country-level achievement are standardized (mean = 0; standard deviation = 1) in order to facilitate comparison of effect sizes.

3.1.3 Covariates in PISA

The study discusses causal relationships, in which case confounding becomes an issue. However, if the treatment (country-level achievement) is itself a proxy for a bundle of more specific policies and practices, how can confounders be separated from the treatment itself? To deal with this, I will defer to the notion of trade-offs, which is focused on what goes on in the education system. Hence, the goal is to remove the influence from factors that are largely outside the influence of education systems (i.e. confounders), but not from factors directly related to education systems (Woessmann, 2016).

In analyses of school belonging, the inclusion of country fixed effects (see below) is the main strategy used to adjust for confounding at the country-level. In the analyses of the remaining outcomes, I am restricted to adjusting for observed confounders. I use three sets of covariates for this purpose. First, I adjust for individual socio-economic characteristics: gender (0 = boy; 1 = girl), migration background (0 = native; 1 = foreign-born parents; 2 = foreign born and foreign born parents) and parental education (ISCED 0–5). With the richer data available in the 2018 wave, I also adjust for parental wealth and the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status. Second, I adjust for country-level socio-economic characteristics: GDP per capita (World Bank, 2022a), unemployment rate (World Bank, 2022b), average education level (derived from PISA data) and share of immigrants (derived from PISA data). These basic socio-economic characteristics may affect both achievement and wellbeing, but are not caused by the education system, except in the very long-term, and so adjusting for them does not lead to overcontrol bias (Elwert & Winship, 2014). Third, with the richer data available in the 2018 wave, I also adjust for availability of a smart-phones, how frequently pupils use social media, and the PISA index of parental emotional support (e.g. items such as “My parents support me when I am facing difficulties at school”). Smart phones and social media are measured at both the individual and country levels to account for contextual effects of digital interactions. This third set of covariates is extraneous to the education system, possibly related to achievement and wellbeing, and hence potentially confounders. However, it is difficult to á priori determine whether they affect achievement and wellbeing more than the other way around.

3.2 Complementary data from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study

A major limitation with existing studies on trade-offs between achievement and wellbeing is that they have relied on cross-sectional data (Montt & Borgonovi, 2018; OECD, 2017). PISA includes one measure of wellbeing (school belonging) that is available in several waves and possible to analyze longitudinally. However, in order to gain more temporal variation in measures of pupil wellbeing, and thereby enable more credible causal inferences to be made, I have matched country-level achievement data from PISA with individual data on wellbeing from HBSC.

Similarly to PISA, HBSC is a repeated and internationally harmonized cross-sectional survey of pupils, but focused on health and wellbeing. It is conducted every fours years in collaboration with the World Health Organization. HBSC collects representative data on three age groups – aged 11, 13 and 15 years – with a sample size of around 5,000 students per country and survey (Roberts et al., 2009). HBSC covers all European countries included in this study, as well as Canada and the USA, but not the Asian, Australasian or Latin American countries. 34 countries in total can be matched with PISA (see Supplementary file A for a complete list). I use data on 15-year old pupils from the 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014 and 2018 surveys, that is, five measurement points over a 16 year period. I match individual data from the five HBSC waves with the average achievement in each country and year from the closest preceding or simultaneous PISA survey. That is, the 2002 HBSC wave is matched with the 2000 PISA wave, the 2006 HBSC wave with the 2006 PISA wave, the 2010 HBSC wave with the 2009 PISA wave, the 2014 HBSC wave with the 2012 PISA wave, the 2018 HBSC wave with the 2018 PISA wave.

3.2.1 Outcome Variables in HBSC

HBSC have data on school-related stress, life satisfaction and psychosomatic complaints. School-related stress is measured with the question “How pressured do you feel by the schoolwork you have to do?”, with response options “not at all”, “a little”, “some”, “a lot”.

Psychosomatic complaints is measured with the question “In the last 6 months: how often have you had the following…? Headache, stomach-ache, back ache, feeling low, irritability or bad temper, feeling nervous, difficulties in getting to sleep, feeling dizzy”, with response options “about every day”, “more than once a week”, “about every week”, “about every month”, “rarely or never”. I use a generalized partial credit model to construct a continuous index of psychosomatic complaints. Cronbach’s alpha varies from 0.793 to 2002 to 0.834 in 2014.

Life satisfaction is measured with the question “Here is a picture of a ladder. The top of the ladder ‘10’ is the best possible life for you and the bottom ‘0’ is the worst possible life for you. In general, where on the ladder do you feel you stand at the moment?”.

All outcome variables are continuous and standardized (mean = 0; standard deviation = 1) in order to facilitate comparison of effect sizes.

3.2.2 Treatment Variables in HBSC

HBSC does not include individual data on achievement. Country-level achievement is calculated as the average achievement in mathematics in each country and wave, using PISA data.

3.2.3 Covariates in HBSC

With longitudinal data at the level of countries, inclusion of country fixed effects (see below) is the main strategy used to adjust for confounding at the country-level in analyses of HBSC data. To account for influence from time-varying confounders, I adjust for individual and country-level socio-economic characteristics. Country-level characteristics are identical to those used in analyses of PISA data: GDP per capita, unemployment rate, average education level and share of immigrants. With the exception of gender, HBSC and PISA do not include directly comparable measures of individual characteristics. In HBSC, I measure socio-economic status with the consumption level of the respondent’s household. HBSC does not include any measure of migration background.

3.3 Analytical Strategy

I estimate a set of linear regression models with clustered standard errors to account for the dependence of observations within countries. Since the clustered data structure is not of interest per se, clustered standard errors offer a more parsimonious way to account for the clustering than multilevel models (McNeish et al., 2017). I estimate multilevel models in supplementary analyses. I follow the design-based approach to clustering suggested by Abadie et al. (2017), and cluster the standard errors at the level of treatment assignment, which is countries in this case.

Negative and positive affect are investigated in model 1.

Where \({\gamma }_{ic}\) denotes negative or positive affect of pupil i in country c. The focal explanatory variables are \(C{A}_{c}\), which denotes the average achievement in each country and wave, and \({IA}_{ic}\) which denotes each pupil’s deviation from this average. Vectors of the previously described individual- and country-level socio-economic covariates (\({X}_{ic}\) and \({Z}_{c}\), respectively), as well as a vector of additional covariates \({W}_{ic}\)(which includes smart phone availability, social media use and parental support), are included to account for possible confounding.\({\epsilon }_{ic}\) is an individual-specific error term. Moderation (RQ2) is analyzed by adding the interaction term \({IA}_{ic}\)*\(C{A}_{c}\).

School belonging is investigated in model 2.

Where \({\gamma }_{ict}\) denotes school belonging of pupil i in country c and PISA wave t. Model 2 is similar to model 1, except that it adds the \(t\) subscript, denoting variation across survey waves. Model 2 also adds country and wave fixed effects (\({C}_{c}\) and \({T}_{t}\)), which hold all country and time-invariant differences across countries and survey waves constant. Unlike model 1, model 2 does not include the vector of additional coefficients \({W}_{ic}\) since these are not available in all waves. Moderation (RQ2) is analyzed by adding the interaction term \({IA}_{ict}\)*\(C{A}_{ct}\).

Outcomes from HBSC are analyzed in model 3:

Where \({\gamma }_{ict}\) denotes school stress, psychosomatic complaints and life satisfaction of pupil i in country c in HBSC wave t. \({C}_{c}\) and \({T}_{t}\) are country and wave fixed effects, respectively. \(C{A}_{ct}\) denotes country-year average achievement, as described previously. \({X}_{ict}\) is a vector of individual-level covariates that includes gender and household consumption level. \({Z}_{ct}\) is a vector of time-varying country-level socio-economic covariates, as described previously. Note that, because model 3 only includes country-year average achievement, research question 2, concerning moderation of individual-level relationships, cannot be addressed.

Models 1 and 2 are fit on PISA data. Model 3 is fit on individual level HBSC data matched with country-level PISA data.

4 Results

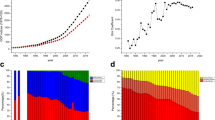

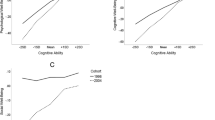

I show the results graphically and report exact coefficients in supplementary file B. Figure 1 shows results from model 1, with negative and positive affect as the outcomes. I include covariates in a stepwise fashion until estimating the full model 1 in the last stage. Markers show point estimates, lines show 95% confidence intervals, and the x-axis show estimated effect sizes. The top rows show results for country-level achievement, the intermediate rows results for individual achievement, and the bottoms rows show interactions between country- and individual-level achievement. Beginning with negative affect (left column), there is a moderately strong and significant positive relationship between country-level achievement and negative affect in the unadjusted model and the model adjusted for socio-economic covariates (circle- and diamond-shaped markers; effect sizes = 0.121–0.132). This is reduced when conditioning on availability of, and reduced again when adjusting for, additional covariates (square- and triangle-shaped markers; effect sizes = 0.092 − 0.053). The final estimates are less than half as large as the unadjusted ones, and not significant. The individual-level relationships (middle rows) are not in focus of the study, but shown as they provide a point of reference for judging the effect sizes of the country-level estimates. The relationships between individual-level achievement and negative affect are consistently very small and non-significant, despite a large sample size. The interaction terms between country-level and individual achievement are also small and non-significant.

Turning to positive affect (right column), the results show a consistently negative but mostly non-significant relationship between country-level achievement and wellbeing; the exception is the model conditioned on additional covariates, where the estimate is significant. The estimates are modest in size and smaller than those for negative affect (between − 0.045 and − 0.101). The individual-level relationships (middle row) are negative and small but mostly significant. The interaction terms between country-level and individual achievement are small and non-significant.

Figure 2 shows results from model 2, with school belonging as the outcome. There is a negative but far from significant relationship between country-level achievement and school belonging (circle-shaped marker). When country and survey wave fixed effects are included (square-shaped marker), however, the estimates turn positive and significant. A standard deviation increase in achievement is associated with almost 0.1 standard deviations higher school belonging. When conditioned on availability of socio-economic covariates (diamond-shaped marker), the estimate becomes somewhat smaller and turns non-significant. Entering the socio-economic covariates (triangle-shaped marker), and thus estimating the full model 1, does not change the estimates. The individual-level relationships are consistently positive, significant, moderately strong (effect sizes around 0.1), and barely affected by inclusion of covariates. The bottom row shows that there is a negative and significant, but fairly small, interaction between country-level and individual achievement. This indicates that the positive relationship between country-level achievement and school belonging is slightly weaker among high-achieving pupils, or in causal terms, that more high-achieving pupils gain less in terms of school belonging from living in a high-achieving country.

Figure 3 shows results from model 3, with school-related stress, psychosomatic complaints and life satisfaction (with data from HBSC) as the outcomes. The left-most column shows that there is no relationship between mathematics achievement and school-related stress. The middle column shows that the relationship with psychosomatic complaints is negative (indicating fewer complaints) in the unadjusted model, but close to zero and non-significant when adjusting for country and year fixed effects and covariates. The right-most column shows a positive relationship with life satisfaction, but this is only significant in the model adjusted for country and year fixed effects but not covariates. The effect sizes are modest, ranging from − 0.09 (unadjusted model with psychosomatic complaints as the outcome) to 0.05 (model adjusted for country and year fixed effects with life satisfaction as the outcome).

Relationships between mathematics achievement and school-related stress, psychosomatic complaints and life satisfaction

Note: Data from PISA 2018. X-axis show school belonging. Markers show point estimates for regression coefficients. Horizontal lines show 95% confidence intervals. Estimates from model 3

4.1 Supplementary Analyses

I have conducted a range of sensitivity analyses. Supplementary file C shows results using wild cluster bootstrap replications to adjust the significance tests for the comparatively small number of clusters. The wild cluster bootstrap adds uncertainty to the estimates, and only for negative affect are estimates significant. Supplementary file D shows that the results are very similar when using average achievement in mathematics, science and reading as the focal treatment variable. Supplementary file E shows that results are similar when estimating multilevel regression models. Much of the discourse of trade-offs have taken the high-achieving East Asian countries as point of reference (Lee & Larson, 2000; Ling et al., 2022). Supplementary file F shows that the estimates for school belonging become more positive and estimates for negative affect less positive, but estimates for positive affect simultaneously become more negative, when East Asian countries are excluded. Thus, while the East Asian countries have some influence on the estimates, the direction of this influence is not consistent across the different outcomes. Supplementary file G shows that the estimates are very similar when HBSC data are matched to the closest PISA wave rather than the closest preceding PISA wave. Supplementary file H shows that the estimates are very similar when I re-estimate the models at the country-year level, using country-year averages of all variables including the outcome variables (cf. Rudolf and Bethmann, 2022). Supplementary file I shows that the overall null-findings are not sensitive to accounting for reverse causation and dynamic effects using cross-lagged panel models with fixed effects.

5 Discussion

The point of departure for this study was two conflicting discourses in education policy: a dominant achievement discourse – focused on standards, testing, competition and accountability – that has been by a challenged by an increased emphasis on pupil wellbeing. These conflicting discourses raise questions regarding possible trade-off between achievement and wellbeing in education.

The first research question (RQ1) asked if country-level achievement is related with individual-level wellbeing. Based on this question, two opposing theoretical arguments were contrasted. Drawing on individual-level studies and influential psychological theories, the case against a trade-off posited that the positive relationship between achievement and wellbeing documented at the individual level can be aggregated, thus generating a “win-win” relationship at the level of countries. Drawing on sociological theories of stratification, the case for a trade-off posited that individual-level studies primarily capture the benefits of relative achievement, which cannot be aggregated, and that competition for higher relative achievement can have negative externalities in terms of wellbeing.

Both discourses received rather weak and inconsistent empirical support. There was a moderately strong positive relationship between country-level achievement and negative affect, and a somewhat weaker negative relationship between achievement and positive affect. However, these relationships were not significant when adjusting for a more comprehensive set of covariates, and moreover only reflected cross-sectional relationships. In the analyses adjusting for stable country characteristics using country fixed effects, the results indicated either a non-existing or a positive but typically not significant relationship between achievement and wellbeing; the latter measured by school belonging, life satisfaction, school-related stress and psychosomatic complaints.

The second research question (RQ2) asked if country-level achievement moderates the relationship between individual-level achievement and wellbeing. Previous research and theory offered scant guidance for specific predictions in this regard, and the study found weak evidence for moderating effects: only one of the three interaction terms between country-level and individual achievement – with school belonging as the outcome – was significant, but the effect size was small. Thus, the null findings regarding average effects do not seem to mask heterogenous effects by individual achievement.

How do the findings of this study relate to previous research on the topic? The vast majority of existing research on the topic has focused on the individual level and mostly found a “win-win” (i.e. positive) relationship between individual achievement and wellbeing (e.g. Kaya and Erdem, 2021). The predominantly null-findings in this study suggests that there is no corresponding composition effect at the country level: although high-achieving pupils have higher wellbeing, more high-achieving pupils in a country does not in general translate into more pupils with high wellbeing. In other words, the “win-win” discourse commits a reverse ecological fallacy by erroneously assuming that individual-level relationships can be aggregated to the level of countries.

Existing research focusing on education systems and country-level achievement is scarcer. Montt and Borgonovi (2018), OECD (2017;, 2019) and Wang (2016) use a similar conceptualization and similar data from international large-scale assessments as in this study and report a negative cross-sectional relationship between country-level achievement and wellbeing. While the cross-sectional results in this study are in line with these findings, the longitudinal results are not. Since the fixed-effects models rely on weaker assumptions – no unobserved time-varying confounding – for causal inference, this suggests that the negative relationships between achievement and wellbeing reported in previous research may reflect unobserved confounding by stable characteristics of countries but not genuine trade-offs.

This study conceptualized the notion of trade-offs in relation to actual country-level achievement. Another but related approach in the literature has been to study trade-offs in relation to specific education policies or practices. For instance, policies that encourage intrinsic motivation have been found to improve both achievement and wellbeing (Ryan & Weinstein, 2009; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006), while frequent and/or high-stakes testing have been found to promote learning (Hattie, 2008; Woessmann, 2016) but harm wellbeing (Högberg & Horn, 2023; Jürges & Schneider, 2010). There is also evidence that “cram schooling” can improve achievement but increase depression among pupils (Kuan, 2018). Given the heterogeneity in the kinds of policies studied it is difficult to draw general conclusions from this literature. However, with the caveat that direct parallels between studies focused on specific policies and studies focused on actual achievement should be made with caution, the overall inconclusiveness of the results from the former line of research is consistent with the predominantly null findings reported in this study. This suggest that, on average across education systems, the prevailing education policies or practices do not prioritize either achievement or wellbeing, but both (or neither). Alternatively, the effects of these policies or practices may go in different directions but cancel each other out, thereby producing zero net effects on average. Thus, while specific policies may be subjected to trade-offs, it does not appear that this is the case for education systems as a whole, at least not systematically.

5.1 Limitations

One limitation of the study concerns the outcome variables. Wellbeing is a broad and multifaceted concept, and the operationalization of wellbeing used in this study does not encompass all aspects that may be relevant for a good life, for instance the emphasis on flourishing central to the eudemonic tradition or the emphasis on agency central to the capability approach (Clarke, 2020; Sen, 2009). Related to this, most of the wellbeing indicators in PISA were only included in the 2018 survey. Although the use of HBSC data to some extent complemented this, it would have been desirable with more temporal variation in the wellbeing indicators.

Another limitation concerns endogeneity bias. Endogeneity may come about through omitted confounding variables. Although the fixed effects models are arguably an improvement compared to the previous cross-sectional evidence (OECD, 2017, 2019) from the perspective of causal inference, they are inferior to more credible quasi-experimental designs or randomized controlled trials, and I cannot rule out that other factors not adjusted for in the models – such as cultural or genetic factors – suppress a positive or negative relationship between achievement and wellbeing. However, note that the reasonably narrow confidence intervals preclude large effect sizes, and a biased null effect would have to be explained by the different sources of bias cancelling each out almost perfectly (VanderWeele et al., 2014). Endogeneity can also occur due to simultaneity or reverse causation. The discourse of a trade-off is premised on an assumed directionality of the causal relationship: it is higher achievement, or policies that emphasise achievement, that is postulated to harm wellbeing, not the other way around. Thus, reverse causation would be present if wellbeing affects achievement (Moilanen, 2010). However, the cross-lagged panel models (Supplementary file I) suggest that reverse causation is not an issue in this case. Endogeneity can also come about through measurement error. The PISA achievement scores used in this study have been criticized as being inaccurate in some countries (Anders et al., 2021), thus impeding comparability across countries. Moreover, since the PISA test carries low-stakes for the pupils, the achievement scores may conflate achievement with effort. To the extent that measurement error is random, this will draw the estimates towards the null, which could partly explain the overall null findings in the study.

A third possible limitation concerns the use of country-level achievement as a proxy for a bundle of more specific policies and practices related to education systems. This approach circumvents the problem that policies may interact in multiple and non-linear ways within education systems, and also provides a more direct test of possible trade-offs. However, the approach means that the arguably more policy-relevant question of whether certain policies can simultaneously promote achievement and wellbeing cannot be answered in this study.

5.2 Conclusion and Implications

This study found that country-level academic achievement is only weakly and inconsistently related with wellbeing. The overall conclusion is thus that higher achievement in education systems does not come at the cost of reduced wellbeing among pupils and that concerns regarding trade-offs between achievement and wellbeing may be unfounded or at least exaggerated. At the very least, the results suggest that improvements in achievement over time within countries does not harm, and may even weakly improve, wellbeing. These results have implications for policy as well as research.

The results concerning changes within countries over time (i.e. from the fixed effects models) are arguably the most relevant from a policy perspective since most policies in the domain of education are national or sub-national in scope, and since policymakers can only influence the (temporal variation in) achievement in their own countries. The predominantly null findings from these models imply that policymakers and the general public should not be concerned that wellbeing must be sacrificed in order to improve achievement, but also that they should not expect miracles in terms of wellbeing from high-achieving education systems. High achievements may be good from an academic perspective, but do not on average seem to make much of a difference from the perspective of wellbeing. One caveat is in order here, however. This study uses linear models and is focused on average achievement and average wellbeing. However, it may be that achievements below a certain threshold, such as thresholds that define basic eligibility requirements, have different effects. Such data are not available in PISA, but there are reasons to expect that raising basic skills and preventing school failure may be particularly beneficial for wellbeing (Moilanen, 2010). While this study cannot answer the related question concerning if or which specific policies are subjected to tradeoffs, to the extent that policymakers and the general public value both achievement and wellbeing, identifying and implementing policies that facilitate both should be a priority. To the extent that specific policies do harm pupils’ wellbeing, policymakers should find ways to counter these through compensatory measures such as investing in school nursing and counselling.

As for implications for research, the, in some cases marked, differences between the cross-sectional and the longitudinal results underlines the need to examine how sensitive cross-sectional relationships are to time-constant unobserved confounding. The study also illustrates how combining different international assessments can enhance the generalisability and external validity of empirical patterns. Moreover, the key finding of the study – that country-level achievement per se does not seem to be very consequential for wellbeing – implies that sweeping statements regarding trade-offs or win-win relationships obscure rather than enlighten scholarly discussions of education policy. A more fruitful starting point may be to concentrate on the content of specific policies in order to identify policies that may combine both achievement and wellbeing simultaneously.

Data Availability

The PISA data used for the analysis are publicly available at the OECD webpage: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/. The HBSC data used for the analysis are publicly available at the HBSC webpage: https://www.uib.no/en/hbscdata/113290/open-access. The Stata code for replication of the results from this paper will be made available after publication.

References

Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G. W., & Wooldridge, J. (2017). When Should You Adjust Standard Errors for Clustering? NBER Working Paper No. w24003.

Amholt, T. T., Dammeyer, J., Carter, R., & Niclasen, J. (2020). Psychological wellbeing and academic achievement among school-aged children: A systematic review. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1523–1548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09725-9.

Anders, J., Has, S., Jerrim, J., Shure, N., & Zieger, L. (2021). Is Canada really an education superpower? The impact of non-participation on results from PISA 2015. Educational Assessment Evaluation and Accountability, 33(1), 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09329-5.

Bücker, S., Nuraydin, S., Simonsmeier, B. A., Schneider, M., & Luhmann, M. (2018). Subjective wellbeing and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.02.007.

Clarke, T. (2020). Children’s wellbeing and their academic achievement: The dangerous discourse of ‘trade-offs’ in education. Theory and Research in Education, 18(3), 263–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878520980197.

Collins, R. (1979). The Credential Society: An historical sociology of Education and Stratification. New York: Academic Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Hunter, J. (2003). Happiness in Everyday Life: The uses of experience sampling. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024409732742.

Denscombe, M. (2000). Social conditions for stress: Young people’s experience of doing GCSEs. British Educational Research Journal, 26(3), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/713651566.

Domina, T., Penner, A., & Penner, E. (2017). Categorical inequality: Schools as sorting machines. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053354.

Ebesutani, C., Regan, J., Smith, A., Reise, S., Higa-McMillan, C., & Chorpita, B. F. (2012). The 10-Item positive and negative affect schedule for children, child and parent shortened versions: Application of Item Response Theory for more efficient Assessment. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-011-9273-2.

Eccles, J. S., & Midgley, C. (1989). Stage/environment fit: Developmen-tally appropriate classrooms for early adolescents. In R. E. Ames, & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education (pp. 139–186). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Ecclestone, K., & Hayes, D. (2008). The dangerous rise of therapeutic education. London: Routledge.

Elwert, F., & Winship, C. (2014). Endogenous selection Bias: The Problem of Conditioning on a Collider Variable. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043455.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218.

Grek, S. (2009). Governing by numbers: The PISA ‘effect’ in Europe. Journal of Education Policy, 24(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802412669.

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Heller-Sahlgren, G. (2018a). The achievement – wellbeing Trade-Off in Education. London: Centre for Education Economics.

Hirsch, F. (1978). Social limits to growth. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Högberg, B., & Horn, D. (2023). National high-stakes testing, gender and school stress in Europe – A difference-in-difference analysis. European Sociological Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcac009.

Holland, P. W. (1986). Statistics and causal inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81(396), 945–960. https://doi.org/10.2307/2289064.

Jürges, H., & Schneider, K. (2010). Central exit examinations increase performance… but take the fun out of mathematics. Journal of Population Economics, 23(2), 497–517. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20685328.

Kaya, M., & Erdem, C. (2021). Students’ wellbeing and academic achievement: A Meta-analysis study. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1743–1767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09821-4.

Kuan, P. Y. (2018). Effects of Cram Schooling on Academic Achievement and Mental Health of Junior High Students in Taiwan. Chinese Sociological Review, 50(4), 391–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2018.1526069.

Layard, R., & Hagell, A. (2015). Chap. 6: Healthy young minds: Transforming the Mental Health of Children. In J. Helliwell, R. Layard, & J. Sachs (Eds.), World Happiness Report 2015. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Lee, M., & Larson, R. (2000). The korean ‘Examination hell’: Long hours of studying, distress, and Depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(2), 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005160717081.

Ling, X., Chen, J., Chow, D. H. K., Xu, W., & Li, Y. (2022). The “Trade-Off” of Student Wellbeing and Academic Achievement: A perspective of Multidimensional Student Wellbeing. Frontiers in psychology, 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.772653.

Luthar, S. S., Barkin, S. H., & Crossman, E. J. (2013). I can, therefore I must”: Fragility in the upper-middle classes. Development And Psychopathology, 25(4 Pt 2), 1529–1549. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579413000758.

Lv, B., & Lv, L. (2021). Out-of-School Activities on Weekdays and Adolescent Adjustment in China: A person-centered Approach. Child Indicators Research, 14, 783–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09778-w.

McNeish, D., Stapleton, L. M., & Silverman, R. D. (2017). On the unnecessary ubiquity of hierarchical linear modeling. Psychological Methods, 22(1), 114–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000078.

Mintz, A. I. (2012). The happy and suffering student? Rousseau’s Emile and the path not taken in progressive educational thought. Educational Theory, 62(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2012.00445.x.

Moilanen, K. L., Shaw, D. S., & Maxwell, K. L. (2010). Developmental cascades: Externalizing, internalizing, and academic competence from middle childhood to early adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000337.

Montt, G., & Borgonovi, F. (2018). Combining achievement and wellbeing in the Assessment of Education Systems. Social Indicators Research, 138(1), 271–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1644-y.

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results (volume III): Students’ wellbeing. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2018). PISA 2018 Technical Report. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume III): What School Life means for students’ lives. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Park, J. Y., & Chung, I. J. (2014). Adolescent suicide triggered by problems at School in Korea: Analyses focusing on Depression, suicidal ideation, Plan, and attempts as four dimensions of suicide. Child Indicators Research, 7, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-013-9197-3.

Ramey, G., & Ramey, V. A. (2009). The Rug Rat Race. NBER Working Paper No. 15284.

Roberts, C., HBSC Study Group International., et al. (2009). The Health Behaviour in School-aged children (HBSC) study: Methodological developments and current tensions. International Journal of Public Health, 54(Suppl 2), 140–150.

Rudolf, R., & Bethmann, D. (2022). The Paradox of Wealthy Nations’ low adolescent life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00595-2. (online publication).

Rudolf, R., & Lee, J. (2023). School climate, academic performance, and adolescent well-being in Korea: The roles of competition and cooperation. Child Indicators Research, 16, 917–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-10005-x.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

Ryan, R. M., & Weinstein, N. (2009). Undermining quality teaching and learning: A self-determination theory perspective on high-stakes testing. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104327.

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Stentiford, L., Koutsouris, G., & Allan, A. (2021). Girls, mental health and academic achievement: A qualitative systematic review. Educational Review, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.2007052.

Sweeting, H., West, P., Young, R., & Der, G. (2010). Can we explain increases in young people’s psychological distress over time? Social Science and Medicine, 71(10), 1819–1830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.012.

UNICEF. (2009). Child-friendly schools manual a reference and guidebook to help implement child-friendly schools. New York: UNICEF.

VanderWeele, T. J., Tchetgen, E. J., Cornelis, M., & Kraft, P. (2014). Methodological challenges in mendelian randomization. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 25(3), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000081.

Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic Versus extrinsic goal contents in self-determination theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4101_4.

Wang, L. C. (2016). The effect of high-stakes testing on suicidal ideation of teenagers with reference-dependent preferences. Journal of Population Economics, 29(2), 345–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-015-0575-7.

Woessmann, L. (2016). The importance of School Systems: Evidence from International differences in Student Achievement. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.3.

World Bank (2022a). GDP per capita (constant 2015 US$). Retrieved August 7, 2020 from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.

World Bank (2022b). Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate). Retrieved August 7, 2020 from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS.

Funding

The work on this article (planning, analysis and writing) was funded by VR, the Swedish Research Council (grant number 2018–03870_3), and by FORTE, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (grant number 2022 − 01062).

Open access funding provided by Umea University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statement Regarding Informed Consent

Pupils participating in PISA and HBSC are given written information stating that their participation is voluntary and that their answers are confidential.

Statement Regarding Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Reference 2019_00013).

Statement Regarding Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The author have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Högberg, B. Is There a trade-off Between Achievement and Wellbeing in Education Systems? New cross-country Evidence. Child Ind Res 16, 2165–2186 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-023-10047-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-023-10047-9