Abstract

School bullying is a growing concern in almost all developed economies, bringing negative and serious consequences for those students involved in the role of victims. In this paper, we propose to analyze this topic for the case of Spain, considering the data compiled in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) report in 2018. The sample size consists of 12,549 15-old-year students (51.84% females and 48.16% males). With the help of structural equation models (SEM), we aim to detect the relationship between the risk of being a victim of bullying and several self-appreciations expressed by the students. We have considered variables that try to measure individual perceptions in several aspects, such as the self-image, the help provided by parents and teachers and how the school environment’s safety is perceived. A multigroup analysis was also performed to see the impact of the socioeconomic level of the families and the students’ academic performances on the proposed model. We conclude that several of those aspects are directly related with the risk of being bullied and this risk is higher in those students who present school failure and have a lower socioeconomic status. In this regard, the results would permit pointing out some aspects in which the decision-makers can focus their proposals to establish prevention measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Education must be seen as one of the main factors that impact on the progress and development of individuals and societies. It not only provides knowledge, it is also a vehicle to fortify positive values that, as a society, we need to develop. Education has proven itself to be a valuable tool to improve welfare standards, reduce social inequalities and guarantee a sustained economic growth. In that line, it should be considered as one of the sources in the sustainable development of economies.

From an individual point of view, every phase of the educational process is a significant step in the individual’s development. And at every one of those stages both the schools and the families are the main support for the development of teenagers. The contents and values they receive at these centers and obtain from their families will be used as the basis to prevent the formation of undesired behaviors. The salience of these contexts justifies the importance of guaranteeing that schools should be a safe place.

Peer violence in schools is a widespread and growing phenomenon that concerns most societies around the world. One of the forms of violence that has been attracting attention in the last decades is bullying. This is defined as “a behavior of physical and/or psychological persecution carried out by one or several students against another student who is chosen as the victim of repeated attacks” (Olweus, 1993). The most defining characteristic of bullying is the existence of a systematic abuse of power and an unequal power relationship between the bully and the victim (Pellegrini & Long, 2002; Salmivalli & Peets, 2008). Many researchers have shown that bullying is not an isolated problem, exclusive of certain countries or cultures. On the contrary, it is widely extended in societies all over the world (Cook, et al., 2010a; Eslea, et al., 2004).

The literature has studied the problem of bullying as a group phenomenon. In addition to the main participants, bullies and bully victims, the remaining students are part of the process, assuming different roles. Hence, we can find reinforcers of the bully, defenders of the victim, or passive bystanders. Adverse behavioral and psychological outcomes have been found for all the referred groups (Rivers, et al., 2009; Salmivalli, 2010).

With respect to actions, bullying can be classified into three main categories (Olweus, 1993): physical, that includes pushing, kicking, taking belongings…; verbal, including performances like name-calling, teasing, threatening, etc.; and relational, including public humiliation and social exclusion. Considering the form of interaction, the actions can be direct or indirect. The former includes those physical and verbal behaviors that occur face-to-face (pushing or verbal harassment). The latter involves those attitudes in which the victim or the bullies are not necessarily present, for instance, spreading malicious rumors, and relational aggression (Olweus, 1993). This last form of victimization is more difficult to detect and remove. In fact, most analyses of bullying victimization have found that students more commonly report indirect forms of bullying as opposed to the direct physical form of bullying (Dinkes, et al., 2007; Wang, et al., 2009).

It has been shown that these categories of bullying do not occur in schools with the same incidence and intensity. Moreover, the prevalence of each type of actions is related with different aspects such as the students’ ages, the country’s culture, gender, and the socioeconomic level, among others. With respect to students’ ages, the rates of bullying vary significantly from one grade to another. On the whole, the risk of being a victim of bullying declines as we move forward to the next school level: it reduces as the students pass from elementary to middle school and from middle school to high school (Khoury-Kassabri, et al., 2004; Rigby, 2002). Other studies that highlight the relation between bullying and the students’ ages are, among others, those ofÁlvarez-García et al. (2015); Cook, et al., 2010b); Saarento et al. (2015).

Regarding the role of gender, the literature shows that boys are more frequently involved in bullying than girls (Álvarez-García, et al., 2015; Cook, et al., 2010b; Smith, et al., 2019). Boys are implicated more frequently in both roles, as victims and bullies, especially in those actions that include physical aggressions. On the contrary, girls are involved in those actions that involve indirect aggressions: teasing or gossiping about peers or relational victimization (Bradshaw, et al., 2015; Carbone-Lopez, et al., 2010; Tiliouine, 2015).

There are also studies analyzing a possible relationship between bullying victimization and socioeconomic status (Allen, et al., 2022; Jain, et al., 2018). In Tippett & Wolke (2014) we can find a review of the published literature on bullying in schools related with socioeconomic status. In the analysis, the authors found that victimization was positively associated with low socioeconomic levels and negatively associated with high socioeconomic levels. In the same line, Tiliouine (2015) indicates that victims of bullying came from less advantaged families and present more frequent absenteeism at school.

From the premise that bullying is a very complex process in which many interrelated variables should be considered, the aim of this study is the analysis of the main factors associated with the risk of being a victim of bullying attitudes. We have considered a quantitative approach to analyze the importance of several aspects, such as the performance of the family, teachers, the environment provided by the school and the students’ self-esteem. The target is to analyze if certain aspects can be considered as determinant for an individual to be a victim of bullying.

We have considered the information provided by the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) report from 2018. In our view, students aged 15 are at a crucial moment in their physical and emotional development. The PISA reports include not only academic performance data. A large amount of context information is included in every report that permits obtaining a broad picture of the situation of students in every country. In particular, we have considered three main aspects of their life that influence how they feel: how satisfied they are with how they look, with their relationships with their parents, and with life at school (OECD, 2019b).

1.1 Literature Review

There is a large body of research on the problem of bullying. It is one of the main topics in the field of education because of its social impacts. We can find some systematic investigations that try to analyze the risk factors from a global perspective, examining individual and contextual factors that have proven to be correlated with bullying. In this line, we come across works mainly focused on reviewing the literature and meta-analyses at the level of the individual’s characteristics. Examples of these works are the studies of Álvarez-García et al. (2015); Cook, et al., 2010b); Lopez et al. (2011). Other papers have proposed a systematic review of the existing literature at a school and classroom level, analyzing which factors are directly related with bullying situations; see, among others Azeredo et al. (2015), and Saarento et al. (2015). Other works have tried to analyze the predictive value of specific factors, such as the socioeconomic status (Tippett & Wolke, 2014), empathy (Van Noorden, et al., 2014), and the role of parents (Lereya, et al., 2013; Nocentini, et al., 2019).

Other meta-analysis papers that analyze the consequences of bullying victimization are those of Gini and Pozzoli (2009), Moore et al. (2017), (with a particular interest in psychosomatic problems), Hansen et al. (2012) (analyzing psychological factors), and Hawker and Boulton (2000) (which proposes the study of psychosocial maladjustment).

Much of the research uses quantitative methods to deal with the problem. In particular, a number of studies propose the analysis of relations among variables using structural equation models (SEM), which will be the basis of our subsequent analysis. In this line, there is the work of Gini et al. (2007), which shows the relations between empathy and individual behavior in bullying situations, differentiating between pro-bullying and defending-bullying individuals. Considering a sample of Italian adolescents, it presents two possible factors (the cognitive component and the emotional aspect of empathy) that can influence the behavior of individuals against bullying (for both active defenders and passive bystanders). In a posterior paper, Gini et al. (2008), the relevance of gender and social self-efficacy is incorporated into the analysis and Pozzoli and Gini (2012) analyze the attitudes toward bullying.

In Roland and Idsøe (2001) the authors study how proactive (emotions involved in the aggressor) and reactive (the social event that induces the behavior) aggressiveness were related to bullying. In Meyer-Adams and Conner (2008) the victimization by bullying is analyzed, identifying those risk factors in the psychosocial environment of the school. Other authors find mediating effects of emotional symptoms on the association between homophobic bullying victimization and problematic internet/smartphone (Li, et al., 2020) or the mediating effect of regulatory emotional self-efficacy on the link between self-esteem and school bullying (Wang, et al., 2018).

Additional factors, such as the school climate, satisfaction at school, and schoolwork-related anxiety are included in the models in an attempt to explain satisfaction in life and well-being. Examples of this working line are the papers from Borualogo and Casas (2023), Huang (2020), Tiliouine (2015), and Varela et al. (2019, 2021). The connection between the school climate and bullying victimization was studied by Chen et al. (2020) from a cross-country perspective.

It is important to bear in mind that bullying could have very serious consequences. Hence, some studies have shown a relevant link between non-fatal suicidal behaviors and bullying victimization (Zhao, et al., 2022), and the different bullying experiences: bullies, victims, and bully-victims (Wu, et al., 2021). In Zhang et al. (2022), the mediating role of the family, anxiety and resilience is analyzed.

In this context, we propose to analyze the relevance of students’ perceptions about the help and support provided by parents, teachers, and the school when the risk factors of being a bullying victim are measured.

1.2 Theoretical Background

The theoretical framework of the present study is based on the theories of the social-ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and person- and stage-environment fit (Eccles, et al., 1993), in the sense that social settings can impact on the human behavior and human development. Specifically, we draw on social learning theory to emphasize that individuals learn from their family, peers, and prior events (Bandura, 1973). Learning by seeing and doing is the foundation of social learning theory of bullying. In this regard, we refer to the immediate context in which the adolescent is directly involved, and we consider the parent-child relationship, the role of the teachers, and the safety at school.

The aim of this work is to study the relationships between bullying victimization and students’ own perceptions of their parents, teachers, school safety, and positive self-beliefs. A multigroup analysis was also carried out to see the impact of the socioeconomic level of the families and the students’ academic performances on the proposed model. There are few studies that jointly relate all the characteristics that we consider in the proposed model, which includes the analysis of the impact of the socioeconomic and cultural level and academic failure. The existing relationships of each or several of the characteristics considered have been partially studied. We believe that it is essential to analyze all of them as a whole in order to have a vision as close as possible to reality.

1.3 Hypothesis of the Model

The main idea is to consider the students’ perceptions about the help and support provided by parents, teachers, and the school, as well as their opinion of themselves, as feasible causes behind the bullying phenomenon. Teenagers at the end of secondary education experience physical and psychological changes that decisively influence their intrapersonal and interpersonal behaviors. Due to social pressure from friends and classmates, they often disregard the advice of their parents and teachers. For this reason, we consider the analysis from the student’s point of view to be a key aspect. Likewise, the connections between family variables and school bullying practice or victimization have been documented in different papers (Foster & Brooks-Gunn, 2013; Patton, et al., 2013). Distinct aspects of this relationship can be contemplated as key aspects in the students’ welfare.

To carry out this analysis, the following hypotheses are put forward, which we will explain below.

1.3.1 Student Relationships with Their Parents, and Bullying Victimization

Previous studies highlighted that the action of parents within families is fundamental when it comes to instilling values in their children and giving them support to recognize and solve problems (Oliveira, et al., 2020; Patton, et al., 2013). Some studies reveal that warm and supportive parental relationships are related to child’s social and emotional well-being even in the context of exposure to adversity (Kim-Cohen, et al., 2004; Murphy, et al., 2017). Similarly, Davis-Kean et al. (2021) point out that the parents’ educational support is directly related with their affective environment.

At that point, the perceived parental support is crucial to maintain self-esteem, the psychological well-being, including positive self-beliefs and reduced levels of internalizing symptoms (Boudreault-Bouchard, et al., 2013; Dutton, et al., 2020). Studies show that positive parental factors, such as support and positive parent-child relationships, help adolescents feel better about themselves, have positive feeling about themselves and have greater life satisfaction (Van der Kaap-Deeder, et al., 2017; Raboteg-Saric & Sakic, 2014). In some way, the former results point out that the role that families play in bullying prevention is fundamental (Arseneault, et al., 2010; Ttofi & Farrington, 2009). In addition, positive relationships and interaction between parents and children reduce the possibility of being bullied and play a role in the emotional adjustment of victims of bullying, making interventions for victims more successful (Lereya, et al., 2013; Zych, et al., 2019). In contrast, low social support and poor interpersonal relationships could increase the risk of students being victims of bullying (Hong, et al., 2012; Patton, et al., 2013).

In view of the above, it is reasonable to hypothesize:

H1: Parents´ educational support influences the emotional support they give their children.

H2: Parents´ emotional support influences the student’s self-efficacy.

H3: Parents´ emotional support influences the student’s positive feelings.

1.3.2 Self-efficacy, Positive Feeling, self-image and Bullying Victimization

Positive self-related cognitions, defined as children`s thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes about themselves, such as self-efficacy, self-respect or self-image are identified in the literature as being considered protective factors in the victimization of bullying (see Cook et al. (2010b) for a complete revision).

Negative affectivity, i.e., having negative feelings about the environment and oneself is related to being introverted, having a low self-esteem and a negative self-image. The appearance of these children together with a nervous temperament means a risk of victimization (Hansen, et al., 2012). Several researchers have reported the positive association between low self-esteem and school bullying (Gendron, et al., 2011; Tsaousis, 2016).

With respect to their emotions and the perception that they have about themselves we consider students’ self-efficacy, positive feelings and self-image, and it can be hypothesized that.

H4: The student´s positive feelings are related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

H5: The student’s self-efficacy is related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

H6: The student’s self-image is related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

1.3.3 Sense of Belonging to the School, Teacher Support, and Bullying Victimization

The school environment and the relationship of its members with the student and the relation with bullying has been extensively studied (Azeredo, et al., 2015; Saarento, et al., 2015). The student-teacher relationship and the connections with school are relevant to bullying behavior (Gendron, et al., 2011; Raskauskas, et al., 2010).

Adolescents who feel less close to their school and their members are more likely to be victims of bullying and have less satisfaction with their lives (Varela, et al., 2019, 2021). On the contrary, negative factors of the school environment (e.g., a lack of decisions and rules in the face of bullying by the management and teachers, a negative school climate perceived by students) can lead to an increase in the frequency of bullying, aggression, and victimization (Cook, et al., 2010b; Goldweber, et al., 2013). Hence, we can consider the students’ feelings of belonging to the school, understood as the feeling of respect and acceptance that the students have toward the school, as a key aspect in this topic.

On the other hand, teachers play a key role in this process. Although there are studies that show discrepancies between how teachers and staff perceive bullying compared to their students (Bradshaw, et al., 2007; Waasdorp, et al., 2011), the influence of positive teacher-student relationships, as well as teacher involvement, have a great implication in bullying prevention (Espelage, et al., 2014; Saarento, et al., 2015). Teacher support is a protective factor in bullying (Álvarez-García, et al., 2015; Azeredo, et al., 2015), as they often play an important role in advising students how to respond to bullying. (Sokol, et al., 2016; Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2015).

With respect to the student’s life at school, we consider that the following hypotheses can be formulated:

H7: A sense of belonging to the school is related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

H8: The teacher`s support is related with the child’s perception of being bullied.

1.3.4 Influence of Academic Success or Socioeconomic and Cultural Status of Students

The scientific literature shows that concrete indications about the influence of bullying on academic performance can be found (Huang, 2022; Riffle, et al., 2021). In this paper, we have considered a multigroup analysis to analyze the influence of the academic performance on the results obtained from the proposed SEM model. In a similar way, previous studies (see, among others, Allen et al. (2022) and Jain et al. (2018), pointed out the influence of the socioeconomic level. An additional analysis has been also performed considering the socioeconomic level as a differential factor.

2 Methods

Based on the hypotheses formulated above, a model based on structural equations is proposed and computed. SPSS and AMOS software were used to examine the variables and the fitness of the proposed model.

2.1 Dataset

This study analyses Spanish data from the 2018 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). This program has been designed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to collect information about 15-year-old students in the participating countries and economies. A two-stage stratified sampling method was adopted (schools are first sampled and then students are sampled in the participating schools) (OECD, 2009). In schools were there were fewer than 42 age-eligible adolescents, all students aged 15 were selected.

In this study the sample size consists of 12,549 students. There were 6,505 females (51.84%) and 6,044 males (48.16%).

2.2 Measures

All the variables have been calculated from the PISA report published data. The latent and observable variables are summarized in Table 1, note that some observable variables have been removed after the factorial structure. Following the practical suggestion from Kline (2015), the number of variables selected to represent latent variables vary from 3 to 5. The selection of the items in the measurement of each latent variables is based on literature review and theoretical foundations of SEM (Bollen, 1989). In some cases, we have suppressed some non-representative items by considering a mixed procedure which include factorial analysis and Cronbach alpha coefficient (Brown, 2006). It is important to bear in mind that some constructs can be more difficult to measure and, consequently demands a larger number of items for an adequate representation (Bollen, 1989).

Due to correlation problems, item BE2 has been defined negatively for the structure of the three observable variables of the sense of belonging to converge correctly. Also, an exploratory factor analysis was carried out with SPSS, with varimax rotation, in order to identify the adequacy of the items or indicators to each construct. Because of that, some indicators were deleted to properly define the internal structure of the model. Based on this, the constructs were defined by the items presented in Table 1.

The academic performance has been defined with two feasible values: success and failure. We have estimated the levels of proficiency in Mathematics and Science (this has not been done in the case of language since this information is not available for the case of Spain) following the recommendations provided by PISA, which establishes six levels of proficiency. Each successive level is associated with increasingly difficult tasks passed by the student. The students are considered to have failed academic performance if they do not reach level 2 of proficiency in any of the subjects, this is the minimum level of proficiency established in the context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (OECD, 2009).

On the other hand, we have constructed a new variable to represent the socioeconomic level. We have considered three levels (low, medium, and high) based on the Economic, Social and Cultural index (ESCS index) provided by PISA (OECD, 2019a). We have considered that students with ESCS values lower than the 25th percentile constitutes the group with a low socioeconomic level and those included at the 75th percentile the group with a high socioeconomic level.

Based on the hypotheses formulated in the previous section, the proposed model is the one represented in Fig. 1.

2.3 Procedure

Four phases of data analysis were completed in accordance with the method advised by various authors (Frash & Blose, 2019). Firstly, a descriptive analysis using SPSS was used to determine the sample’s demographic characteristics. Secondly, to assess the suitability of the constructs’ dimensions, an exploratory factor analysis using varimax rotation was performed by means of SPSS. Thirdly, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out using AMOS software to verify the measurement model. Fourthly, the structural model’s validity was examined. Finally, to confirm the relationships between the latent variables, the structural model’s coefficients were computed using AMOS software.

3 Results

This section presents the analysis of the results obtained for the proposed model. The dataset has been analyzed by means of AMOS-IBM software.

The internal structure of latent variables and indicators has been assessed by means of factorial analysis. The internal consistency of the scales was measured through the Cronbach alpha coefficient, obtaining in all cases values greater than the 0.7 threshold.

The data normality was also analyzed, checking if the skewness coefficient was between − 1 and 1, and that the kurtosis coefficient was between − 7 and 7. Most of the items were normal, although there were some cases in which this hypothesis was not verified. On the other hand, multivariate normality was measured by means of the Martia test. The multivariate normality hypothesis was rejected because the value of the Martia test was 251.048 (> 5.99 for a significance level of 5%), the critical ratio being greater than the required 1.96. Thus, multivariate normality is not supported. However, since the sample is large enough, it has been decided to opt for the maximum likelihood estimation method, because this method facilitates the convergence of the estimates even in the absence of multivariate normality (Lèvy, et al., 2006).

The assessment of the proposed model has been carried out by analyzing the measurement model and the structural model. Reliability and validity have been used for the assessment of the measurement model. Regarding the first issue, the reliability of the items and the reliability of the constructs have been analyzed.

For the reliability of the items, it was found that the standardized factor loads were greater than the 0.707 threshold. This implies that the shared variance between the construct and its indicators is greater than the error variance. In this way, more than 50% of the variance of the observable variable (communality) is shared by the construct. In any case, some authors consider that a factor loading greater than 0.5 is also acceptable (Chau, 1997). All the standardized factorial loads are greater than 0.707, except those of items EF1, BE2 and BU3, which are greater than 0.5, so the reliability of the items is verified (Table 2).

The Cronbach alpha coefficient and the Composite Reliability (CR) coefficient were used for the assessment of the constructs’ reliability. All the Cronbach alpha coefficients were greater than 0.7, so the reliability is high. The minimum required value of the composite reliability coefficient is 0.7 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). In Table 2, we can see that all the constructs have a CR coefficient greater than 0.7, so the reliability of the constructs is also verified.

Convergent validity and discriminant validity were analyzed for the assessment of the measurement model’s validity. The average variance extracted (AVE) was used for the analysis of the convergent validity. Values greater than 0.5 indicate that the construct explains more than the variance of its indicators (Hair, et al., 2014). In Table 2, we can see that all the AVE values are greater than 0.5, except the value of the student’s self-efficacy construct. This value is practically on the limit, so we can say that the convergent validity is verified.

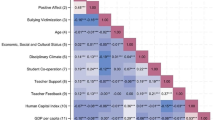

Regarding the discriminant validity, we must verify that the correlations between the constructs are not high or are at least lower than the square root of the AVE. The correlation matrix between the constructs is shown in Table 3. In the main diagonal appears the square root of the AVE. We can see that all the correlations are lower than the square root of the AVE, so the discriminant validity is verified.

With respect to the assessment of the structural model, Table 4 shows that all the coefficients are significative, except the coefficient of the hypothesis H3. On the other hand, the R2 values were greater than 0.1, exceeding this minimum value recommended by some authors, since lower values lack an adequate predictive level, even though significant (Hair, et al., 2014). For all these reasons, we can affirm that the validity of the structural model is verified.

The results of the structural model also reveal a good fit of the data. The χ2 statistic shows if the discrepancy between the original data matrix and the reproduced matrix is significant or not. In this case, the p-value is lower than 0.05; therefore, this hypothesis is rejected. However, it should be noted that the value of the χ2 statistic is highly influenced by the size of the sample, the complexity of the model and by the violation of the multivariate normality assumption. For these reasons, other measurements of global fit are used in AMOS software. In this sense, the remaining measures are consistent with a high degree of fit of the model (RMSEA = 0.042; CFI = 0.956; GFI = 0.950; NFI = 0.955; TLI = 0.952; AGFI = 0.940).

Finally, the total standardized effects have been obtained for analysing the influence of the constructs on bullying. The sense of not belonging is the construct that most influences bullying (total effect of 0.384). This variable is followed in order by student’s positive feeling, student’s self-image, teacher’s support, parents’ emotional support and parents’ educational support, with values of -0.095, -0.090, -0.062, -0.042 and − 0.026, respectively.

To identify if the results obtained from the SEM model are invariant with respect to socioeconomic and academic performance factors, two separate multigroup analyses have been computed, considering the tool developed in Gaskin (2016), which evaluates the differences between critical ratios.

Table 5 summarizes the results for multigroup analysis based on academic performance. We can observe that three relationships are invariant when the results for academic success and academic failure are compared. The relationship between parents’ emotional support and the students’ self-efficacy are higher for those students who are considered as successful in their academic performance. In a similar way, the intensity of the relation between students’ self-efficacy and the risk of being victim, is moderated by the values of academic performance. Finally, the relation between students’ self-image and the risk of being bullied is also affected by the academic performance.

Regarding the influence of socioeconomic values on the results from the SEM model, we do not find significant differences between the groups of low and medium socioeconomic levels. The only remarkable differences emerge with respect to teachers’ support and the risk of being bullied. In this case, those students with a lower socioeconomic level present a greater risk of being bullied. This must be explained by the fact that these group of students are most familiar with unsafe environments (Glew, et al., 2008).

4 Discussion

The results obtained from the computation of the SEM model point out that the feeling of help and support from their parents is a positive factor in the skill development oriented to resolving and overcoming difficult situations and fostering students’ positive feelings. Previous studies support this finding. Dutton et al. (2020) analyzed how perceived parental support influenced positive self-beliefs and is very important for the psychological well-being of adolescents across different cultural contexts.

Regarding positive feelings and the student’s self-image, both are negatively related with being a victim of bullying. However, the student’s self-efficacy and victimization has not been found to be significantly related. Most of the previous studies reported that positive self-related cognitions should be considered as protective factors and a negative association with the victimization of bullying (Cook, et al., 2010b; Gendron, et al., 2011; Tsaousis, 2016). Considering intermediate variables, we can think that there is a relationship between parental educational and emotional support and bullying victimization. This agrees with many other works such as the systematic review by Nocentini et al. (2019).

With respect to the school environment, the support of the teaching staff and the security provided by the educational center have been found significant in preventing the victimization of bullying. The sense of belonging to the school is the construct that presents the most influence. The results found for the school environment are in line with other studies that showed how the students’ relationships with their teachers, as well as the involvement of teachers in the development process of adolescents are relevant to the phenomenon of bullying, mitigating its adverse effects (Espelage, et al., 2014; Gendron, et al., 2011; Raskauskas, et al., 2010; Saarento, et al., 2015). Likewise, feeling displaced and not close to the school is associated with being a victim of bullying (Varela, et al., 2019, 2021).

Considering the theories on social-ecological models (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and the environmental-fit (Eccles, et al., 1993), the bullying victimization is related with their closer environment. In this study, we have considered the students’ context, that is to say, the relations with their parents, teaching staff and school center, as this environment.

The findings suggest that, in the line pointed by the social learning theory, that a main part of the learning process is based on the observation and replication of some behaviors. In addition, this learning process is influenced by their attention and motivation and by the context found by the students.

When we considered the academic success and computed the model for two differentiated groups, all the relationships proposed in the initial model turn out to be significant (with the expected sign), including the relationship between self-efficacy and victimization, which was not in the original model. There are significant differences between the relationships of parental emotional support and the self-efficacy of the children and the victimization, being greater for the advantaged students. The opposite occurs when we compare the relationship between self-image and victimization. The relations between bullying and poor academic performance haven been analyzed is several works; see for instance Huang (2022), Nakamoto and Schwartz (2010), and Riffle et al. (2021), obtaining results in the same line as that described above.

Finally, the analysis performed for the three levels of the socioeconomic status permits seeing how the relations for the higher level are stronger than those obtained in the global model and those obtained for the lower socioeconomic levels. The metanalysis performed in Tippett and Wolke (2014) pointed out how those students with a lower socioeconomic level were more exposed to bullying victimization, which could be explained by the risk of being excluded (because of their limited resources).

5 Concluding Remarks

Peer violence in schools and bullying attitudes is a growing problem for most developed countries. Adolescents constitute a vulnerable group that demands care since certain traumatic experiences lived out in each human being’s life stage can determine his/her future development. Bullying attitudes have relevant consequences, resulting in disorders in those bullied students, even triggering suicide attempts.

This situation has captured the attention of many researchers, a large body of literature on this topic having been developed, including an analysis of causes and consequences, a classification of these activities, and metanalyses. This work is embedded in this context. We have proposed a quantitative analysis, based on Structural Equation Models, to study the relationships of the risk of being bullied with some variables of interest. We have considered the information published in PISA reports, considering the information provided by the students themselves that included self-perceptions about their behavior and experiences in their school stage.

In this paper, we have proposed and computed a quantitative model to detect significant relations of some relevant variables with the risk of being bullied. This ensemble of results could be valuable in the decision-making process. On some occasions the problem of bullying is increased by the lack of interest of educational centers in addressing this problem when it is in its initial phase and trying to silence it (this can be an embarrassing situation for the students or the institutions). Therefore, prevention programs have become an essential tool that must be accessible for teachers and parents to detect the problem as soon as possible. We show that the first warning signs can be obtained from the analysis of public datasets like the ones published in PISA reports.

Several limitations of this study need to be mentioned. One is only using self-reports by the student. Although it is very important to have the students’ perceptions, it would also be desirable to know the perceptions of the school and family environment, which would increase the validity of the results found. Furthermore, a key aspect to be considered as a part of the school environment is the response of the other students. It is important to explore if their response is passive, by defending their classmates or by cooperating with the bullies. Similarly, the consideration of the activity on the social networks should be a key point in future studies. And finally, it is important to point out that the cross-sectional research designs in the current study did not permit to analyze informing causal relationships between the variables.

Future lines of research include broadening and deepening the analysis, including complementary methodologies that permit incorporating contextual variables (the level of income, the level of education, family contexts) and individual information that would enable tailoring conclusions and proposals. Also, the consideration of cyberbullying, which unfortunately are becoming increasingly frequent and not only inside but also outside of the school center, should be an additional aspect to be considered. On the other hand, a cross analysis considering different countries to explore differences between them should be an interesting extension of this study.

Data Availability

All the data considered in this study is derived from public repositories included at the reference Section.

References

Allen, K. A., Cordoba, B. G., Parks, A., & Arslan, G. (2022). Does socioeconomic Status Moderate the relationship between School Belonging and School-Related factors in Australia? Child Indicators Research, 15, 1741–1759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09927-3

Álvarez-García, D., García, T., & Núñez, J. C. (2015). Predictors of school bullying perpetration in adolescence: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.04.007

Arseneault, L., Bowes, L., & Shakoor, S. (2010). Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: ‘Much ado about nothing’? Psychological Medicine, 40, 717–729. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709991383

Azeredo, C. M., Rinaldi, A. E. M., Moraes, C. L., Levy, R. B., & Menezes, P. R. (2015). School bullying: A systematic review of contextual-level risk factors in observational studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 22, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.04.006

Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning theory analysis. Prentice-Hall.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. John Wiley & Sons.

Borualogo, I. S., & Casas, F. (2023). Bullying victimisation and children’s Subjective Well-being: A comparative study in seven asian countries. Child Indicators Research, 16, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09969-7

Boudreault-Bouchard, A. M., Dion, J., Hains, J., Vandermeerschen, J., Laberge, L., & Perron, M. (2013). Impact of parental emotional support and coercive control on adolescents’ self-esteem and psychological distress: Results of a four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescente, 36, 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.05.002

Bradshaw, C. P., Sawyer, A. L., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2007). Bullying and peer victimization at school: Perceptual differences between students and school staff. School Psychology Review, 36(3), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2007.12087929

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & Johnson, S. L. (2015). Overlapping Verbal, Relational, Physical, and electronic forms of bullying in adolescence: Influence of School Context. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(3), 494–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014.893516

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. The Guilford Press.

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F. A., & Brick, B. T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect form of bullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 8(4), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204010362954

Chau, P. Y. K. (1997). Reexamining a model for evaluating information center success using a structural equation modeling approach. Decision Sciences, 28(2), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1997.tb01313.x

Chen, C., Yang, C., Chan, M., & Jimerson, S. R. (2020). Association between School climate and bullying victimization: Advancing Integrated perspectives from parents and cross-country comparisons. School Psychology, 35(5), 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000405

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., & Kim, T. E. (2010a). Variability in the prevalence of bullying and victimization: A cross-national and methodological analysis. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 347–362). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010b). Predictors of bullying and victimization in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020149

Davis-Kean, P. E., Tighe, L. A., & Waters, N. E. (2021). The role of parent Educational Attainment in parenting and Children`s Development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721421993116

Dinkes, R., Cataldi, E. F., Lin-Kelly, W., & Snyder, T. D. (2007). Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2007 (NCES 2008-021/NCJ 219553). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

Dutton, Y. E. C., Choi, I. J., & Choi, E. (2020). Perceived parental support and adolescents’ positive self-beliefs and levels of Distress Across Four Countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00353

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Iver, D. M. (1993). Development during adolescence. The impact of stage-environment on young adolescents´ experiences in schools and in families. The American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101.

Eslea, M., Menesini, E., Morita, Y., O’Moore, M., Mora-Merchan, J. A., Pereira, B., & Smith, P. K. (2004). Friendship and loneliness among bullies and victims: Data from seven countries. Aggressive Behavior, 30(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20006

Espelage, D. L., Polanin, J. R., & Low, S. K. (2014). Teacher and staff perceptions of school environment as predictors of student aggression, victimization, and willingness to intervene in bullying situations. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000072

Foster, H., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2013). Neighborhood, Family and Individual Influences on School Physical victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(10), 1596–1610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9890-4

Frash, R. E., & Blose, J. E. (2019). Serious leisure as a predictor of travel intentions and flow in motorcycle tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(4), 516–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1626118

Gaskin, J. (2016). Stats Tools Package. http://statwiki.gaskination.com

Gendron, B. P., Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2011). An analysis of bullying among students within schools: Estimating the effects of individual normative beliefs, self-esteem, and school climate. Journal of School Violence, 10(2), 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2010.539166

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2009). Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 123(3), 1059–1065. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1215

Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoè, G. (2007). Does empathy predict adolescents´ bullying and defending behavior? Aggressive Behavior, 33(5), 467–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20204

Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoè, G. (2008). Determinants of adolescents’ active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 31(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.002

Glew, G. M., Fan, M. Y., Katon, W., & Rivara, F. P. (2008). Bullying and school safety. The Journal of Pediatrics, 152(1), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.045

Goldweber, A., Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2013). Examining the link between forms of bullying behaviors and perceptions of safety and belonging among secondary school students. Journal of School Psychology, 51(4), 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.04.004

Hair, J. F. J., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Hansen, T. B., Steenberg, L. M., Palic, S., & Elklit, A. (2012). A review of psychological factors related to bullying victimization in schools. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 383–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.008

Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41(4), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00629

Hong, J. S., Espelage, D. L., Grogan-Kaylor, A., & Allen-Meares, P. (2012). Identifying potential mediators and moderators of the association between child maltreatment and bullying perpetration and victimization in school. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9185-4

Huang, L. (2020). Peer victimization, teacher unfairness and adolescent life satisfaction: The mediating roles of sense of belonging to school and schoolwork-related anxiety. School Mental Health: A Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Journal, 12(3), 556–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09365-y

Huang, L. (2022). Exploring the relationship between school bullying and academic performance: The mediating role of students’ sense of belonging at school. Educational Studies, 48(2), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1749032

Jain, S., Cohen, A. K., Paglisotti, T., Subramanyam, M. A., Chopel, A., & Miller, E. (2018). School climate and physical adolescent relationship abuse: Differences by sex, socioeconomic status, and bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 66, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.05.001

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., & Zeira, A. (2004). The contributions of community, family, and school variables to student victimization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(3–4), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-004-7414-4

Kim-Cohen, J., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., & Taylor, A. (2004). Genetic and environmental processes in young children’s resilience and vulnerability to socioeconomic deprivation. Child Development, 75(3), 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00699.x

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, fourth edition. Guilford Publications.

Lereya, S. T., Samara, M., & Wolke, D. (2013). Parenting behaviour and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: A meta-analysis study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(12), 1091–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.001

Lèvy, J. P. M., Martín, M., & Román, M. (2006). Optimización según estructuras de covarianzas. In J. Varela Mallo & J. P. M. Lèvy (Eds.), Modelización con estructuras de covarianzas en ciencias sociales: temas esenciales, avanzados y aportaciones especiales.

Li, D. J., Chang, Y. P., Chen, Y. L., & Yen, C. F. (2020). Mediating Effects of emotional symptoms on the association between homophobic bullying victimization and problematic internet /Smartphone use among gay and bisexual men in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3386, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103386

Lopez, R., Amaral, A. F., Ferreira, J., & Barroso, T. (2011). Factors related to the bullying phenomenon in school context: Integrative literature review. Revista de Enfermagem Referência, 3 (5), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.12707/RIII1169

Meyer-Adams, N., & Conner, B. T. (2008). School Violence: Bullying behaviors and the Psychosocial School Environment in Middle Schools. Children & Schools, 30(4), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/30.4.211

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

Murphy, T. P., Laible, D., & Augustine, M. (2017). The influences of parent and peer attachment on bullying. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(5), 1388–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0663-2

Nakamoto, J., & Schwartz, D. (2010). Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Social Development, 19(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00539.x

Nocentini, A., Fiorentini, G., Paola, L. D., & Menesini, E. (2019). Parents, family characteristics and bullying behavior: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.010

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

OECD. (2009). PISA Data Analysis Manual: SPSS, Second Edition. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264056275-en

OECD. (2019a). PISA 2018 results (volume II): Where all students can succeed. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en

OECD. (2019b). PISA 2018 results (volume III): What School Life means for Students`Lives. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en

Oliveira, W. A., Silva, J. L., Fernández, J. E. R., Santos, M. A. D., Caravita, S. C. S., & Silva, M. A. I. (2020). Family interactions and the involvement of adolescents in bullying situations from a bioecological perspective. Estudios de Psicología (Campinas), 37, 1–12. e180094.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at School: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell Publisher.

Patton, D. U., Hong, J. S., Williams, A. B., & Allen-Meares, P. (2013). A review of research on school bullying among african american youth: An ecological systems analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 25(2), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9221-7

Pellegrini, A. D., & Long, J. D. (2002). A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20(2), 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151002166442

Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2012). Why do bystanders of bullying help or not? A Multidimensional Model. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(3), 315–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431612440172

Raboteg-Saric, Z., & Sakic, M. (2014). Relations of parenting styles and friendship quality to self-esteem, life satisfaction and happiness in adolescents. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9(3), 749–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-013-9268-0

Raskauskas, J. L., Gregory, J., Harvey, S. T., Rifshana, F., & Evans, I. M. (2010). Bullying among primary school children in New Zealand: Relationships with prosocial behaviour and classroom climate. Educational Research, 52(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881003588097

Riffle, L. N., Kelly, K. M., Demaray, M. L., Malecki, C. E., Santuzzi, A. M., Rodriguez-Harris, D. J., & Emmons, J. D. (2021). Associations among bullying role behaviors and academic performance over the course of an academic year for boys and girls. Journal of School Psychology, 86, 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2021.03.002

Rigby, K. (2002). New perspectives on bullying. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Rivers, I., Poteat, V. P., Noret, N., & Ashurst, N. (2009). Observing bullying at school: The mental health implications of witness status. School Psychology Quarterly, 24(4), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018164

Roland, E., & Idsøe, T. (2001). Aggression and bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 27(6), 446–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.1029

Saarento, S., Garandeau, C. F., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Classroom- and school-level contributions to bullying and victimization: A review. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 25(3), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2207

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Salmivalli, C., & Peets, K. (2008). Bullies, victims, and bully–victim relationships. In K. Rubin, W. Bukowski, & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 322–340). Guilford Press.

Smith, P. K., López-Castro, L., Robinson, S., & Görzig, A. (2019). Consistency of gender differences in bullying in cross-cultural surveys. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.04.006

Sokol, N., Bussey, K., & Rapee, R. M. (2016). Teachers` perspectives on effective responses to overt bullying. British Educational Research Journal, 42(5), 851–870. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3237

Tiliouine, H. (2015). School bullying victimisation and subjective well-being in Algeria. Child Indicators Research, 8, 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9286-y

Tippett, N., & Wolke, D. (2014). Socioeconomic status and bullying: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), e48–e59. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301960

Troop-Gordon, W., & Ladd, G. W. (2015). Teachers’ victimization-related beliefs and strategies: Associations with students’ aggressive behaviour and peer victimization. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9840-y

Tsaousis, I. (2016). The relationship of self-esteem to bullying perpetration and peer victimization among schoolchildren and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.09.005

Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2009). What works in preventing bullying: Effective elements of anti-bullying programmes. Journal of Aggression Conflict and Peace Research, 1(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/17596599200900003

Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., & Mabbe, E. (2017). Children’s daily well-being: The role of mothers’ teachers’, and siblings’ autonomy support and psychological control. Developmental Psychology, 53(2), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000218

Van Noorden, T. H. J., Haselager, G. J. T., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Bukowski, W. M. (2014). Empathy and involvement in bullying in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0135-6

Varela, J. J., Guzmán, J., Alfaro, J., & Reyes, F. (2019). Bullying, cyberbullying, student life satisfaction and the community of chilean adolescents. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 14(3), 705–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9610-7

Varela, J. J., Sánchez, P. A., González, C., Oriol, X., Valenzuela, P., & Cabrera, T. (2021). Subjective Well-being, bullying, and School Climate among chilean adolescents over Time. School Mental Health, 13, 616–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09442-w

Waasdorp, T. E., Pas, E. T., O’Brennan, L. M., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2011). A multilevel perspective on the climate of bullying: Discrepancies among students, school staff, and parents. Journal of School Violence, 10(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2010.539164

Wang, J., Iannotti, R. J., & Nansel, T. R. (2009). School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and Cyber. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 368–375.

Wang, X., Zhang, Y., Hui, Z., Bai, W., Terry, P. D., Ma, M., Li, Y., Cheng, L., Gu, W., & Wang, M. (2018). The Mediating Effect of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy on the association between self-esteem and school bullying in Middle School students: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5), 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050991

Wu, N., Hou, Y., Zeng, Q., Cai, H., & You, J. (2021). Bullying experiences and nonsuicidal self–injury among chinese adolescents: A longitudinal moderated mediation model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01380-1

Zhang, H., Han, T., Ma, S., Qu, G., Zhao, T., Ding, X., Sun, L., Qin, Q., Chen, M., & Sun, Y. (2022). Association of child maltreatment and bullying victimization among chinese adolescents: The mediating role of family function, resilience, and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.053

Zhao, H., Gong, X., Huebner, E. S., Yang, X., & Zhou, J. (2022). Cyberbullying victimization and nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: Testing a moderated mediating model of emotion reactivity and dispositional mindfulness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.070

Zych, I., Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2019). Protective factors against bullying and cyberbullying: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.06.008

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from the Ministry of Economy, Knowledge, Business and University, of the Andalusian Government, within the framework of the FEDER Andalusia 2014–2020 operational program. Specific objective 1.2.3. «Promotion and generation of frontier knowledge and knowledge oriented to the challenges of society, development of emerging technologies») within the framework of the reference research project (UPO-1380624). FEDER co-financing percentage 80%.

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad Pablo de Olavide/CBUA.

Funding

All funding sources supporting this research have been acknowledged within the manuscript.

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad Pablo de Olavide/CBUA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have made a substantial contribution to the concept or design of this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

There are no conflicts of interest, either personal or institutional, that have compromised the integrity of the work reported in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Segovia-González, M., Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M. & Contreras, I. Analyzing the Risk of Being a Victim of School Bullying. The Relevance of Students’ Self-Perceptions. Child Ind Res 16, 2141–2163 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-023-10045-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-023-10045-x