Abstract

Our present study sought to qualitative explore the perceptions of experts on the meaning of children agency in a context characterized by ongoing colonial violence and structural racism. Namely, we explored culture and context-specific features of agency, experts’ perceptions about a decolonized definition, and gaps with the mainstream definition of the construct in Western contexts. The study involved 14 participants (N = 8 women), aged between 32 and 70 years with a mean age of 45 years (SD = 9.72) who came from the Gaza Strip, the West Bank (Ramallah, Bethlehem, Hebron and Jenin) and territories currently part of the State of Israel (Jerusalem and Jaffa). They are all mental health professionals in universities, research centres, hospitals and social welfare services. Secondly, the analysis resulted in a map of five themes representing a culturally oriented Palestinian children’s agency model. A threatening context, alleviating factors, healthy agency, aggravating factors, harmful agency. The Palestinian conceptualization of child agency lies in the multifaceted nature of the construct itself re-declined in a context characterized by multiple levels of complexity- cultural, political, social, economic. Our findings might contribute to creating indicators of Palestinian children’s agentic behaviours and a better operationalization of the construct itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The agency concept gained its momentum within psychological sciences starting from the 90’th of the past century thanks to the renewed scholar Albert Bandura (1982, 2006, 2017). The Oxford English Dictionary (second edition) describes the agency as the ‘action or intervention producing a particular effect’ or ‘a thing or person that acts to produce a particular result’. In its development, the construct has been strictly tied to social cognitive theories, looking at the agency as a dynamic system of personal cognitive competencies that allow individuals to gain control over their own experiences, achieve goals and shape structures that inform the ones’ reality (Bandura, 1989, 2001, 2018). Today, agency is a leading concept studied transdisciplinary, from human geography to sociology and anthropology, moving from individualistic perspectives to complex multilevel system theories (Kuus, 2019; Hitlin & Elder, 2007; Majumder, 2021). However, despite its relevance within different disciplines, a simple search within scientific literature shows the many diverse ways the human agency is defined, conceptualized, or operationalized due to weakly described conceptual boundaries and characteristics (Landes & Settersden, 2019).

Moreover, several terms are often used interchangeably with the one of agency, such as ‘self-efficacy’, ‘free will’, or ‘autonomy’, revealing the lack of a clear and shared understanding of its core meaning (Eteläpelto, Vähäsantanen, Hökkä, and Paloniemi, 2013). Indeed, controversies have been raised between an individualistic notion of agency that tends to valorize individuals as main ‘agentic actors’ in their realities from a hand, and the conceptualization of agency as a processual dynamic that is informing both hierarchical structures of power and the social environment, from the other (Swann & Jetten, 2017). Moreover, mainstream social theories stressed the primacy of external circumstances over the individuals’ power to address and anticipate them, diminishing the interest and value of the concept of agency itself (Swann & Jetten, 2017).

In an attempt to move towards a more holistic comprehension of the construct, there is currently a common understanding that factors such as social class, ethnicity, living environment, economic conditions might all influence people’s agency, thus highlighting the need to investigate it within a specific social, cultural, physical and historical context (Eteläpelto et al., 2013; Spyrou, 2018). Indeed, terms such as thin and thick agency (Klocker, 2007) or bounded agency (Evans, 2007; Shanahan & Hood, 2000) highlights the urge to consider agency as a historically, socially and culturally situated construct, as it is ‘bounded’ in social and external structures that shapes, enables or limits it (Edmonds, 2019; Rudnick and Boromisza-Habashi, 2017; Spyrou, 2018).

1.1 Child Agency, Political and Military Violence

The significant effort of the agency theories to study and analyze the human functioning as socially, historically, and culturally situated and determined favoured the proliferation of a consistent body of research on child agency in contexts characterized by extreme poverty, marginalization political and military violence (Kammerbauer & Wamsler, 2017; Gigengack, 2014; Veronese et al., 2019). Several papers have documented agency in children living in war-like conditions (Klocker, 2007; Habashi, 2011; Veronese et al., 2019), focusing on individuals’ actions and reactions concerning situations of oppression or structural violence experienced in everyday life. Moreover, over the last 30 years, agency has been a significant focus within childhood studies concerned over the development of children growing up in contexts marked by war and political violence (Cummings et al., 2017; Prout & James, 1997). Indeed, in a recent literature review, Cavazzoni et al. (2020) have shown the different expressions through which the agency of children living in contexts of war and political violence is displayed and developed. Children’s agentic practices have been documented at the individual, relational, social, and collective levels, developed through social interactions and within specific cultural contexts (Abebe, 2019; Cavazzoni, Fiorini, Veronese, 2020; Spyrou, 2018). Thus, the conceptualization of agency emerges as highly dynamic and strictly interrelated within the social, cultural, material, and spatial worlds in which children’s lives are embodied (Abebe, 2019: Mizen & Ofosu-Kusi, 2013; Spyrou, 2018).

Moreover, the importance of conceptualizing children’s agency as closely connected to and observable only through their everyday context also emerges with what is perhaps among the most controversial issues related to the study of this construct, namely its understanding as an intrinsically positive process (Lokot et al., 2021). Indeed, several scholars have cautioned against the risk of limiting the investigation of children’s agency to its constructive aspects, portraying a sturdy child who does not engage in destructive behaviours (Hoggett, 2001; Gigengack, 2014; Spyrou, 2018). In these terms, agency is no longer conceived as ‘the exercise of choice’ but as ‘the exercise of a good choice’ (Lokot et al., 2021), which unavoidably generates positive outcomes and well-being (Bordonaro, 2012; Durham, 2008). Contrary to this perspective, Gigengack (2008, 2014) highlights that street children often involve themselves in self-destructive practices, significantly undermining their well-being. Similarly, in a recent quantitative assessment of children’s agency within the Palestinian context, Veronese et al. (2019) found a direct and positive relationship between agency and trauma symptoms. This result comes to question whether agency always plays a protective role and points out the need to recognize how children’s agency may enhance their vulnerability. From the scarce literature on this self-destructive agency (Gigengack, 2008) or exaggerated agency (Thompson, 2019) – emerges an evident need to move away from celebrating children’s agency as a mere expression of ‘resistance’ or ‘resourcefulness’, and to explore the contradictory aspects and effects of agency in their lives.

In light of the critical perspectives outlined above, the present qualitative case interview study aimed to explore the perceptions of expert key-informants on the meaning of children’s agency in a context characterized by ongoing colonial violence and structural racism in the occupied Palestinian territories (oPts). More specifically, the paper aims to explore the conceptualization and understanding of the construct of agency - and its manifestations - amongst Palestinian experts and academics who work with children on a daily basis. The purpose was not to explore the agentic practices per se enacted by children (see other studies: Cavazzoni et al., 2021; Veronese et al., 2021a, c - among others), but to reach a more precise conceptualization - situated and culturally significant - of the construct itself and its facets. Accordingly, the present case study can be considered the first step of a larger research project to operationalize qualitatively and quantitatively the construct of agency in Palestinian children affected by war and political violence.

2 Methods

2.1 Recruitment and Participants’ Characteristics

We situated our methodological stance in the tradition of radical critical studies and anti-oppressive approaches (Hashem, 2014; Stewart, 2021). Thus, psychology of liberation and indigenous psychology oriented our reflection toward counter-hegemonic storying in the definition of children agency in Palestine (Burton & Gómez Ordóñez, 2015; Howarth, 2006).

Participants were recruited through snowball sampling (Goodman, 1980), a method widely used for qualitative research with small and hard-to-reach populations. As in this case, the aim was to identify Palestinian health professionals remotely. We adopted three recruitment criteria: Palestinian origin, having lived in the Palestinian territories, and having an established professional experience in the mental health field. The first criterion stemmed from the study’s aim of identifying a culturally oriented conceptual model of child agency. Second, having grown up in the Palestinian territories allowed participants to express first-hand views and experiences related to that context. Finally, the third criterion was related to addressing the issue with professionals in the field.

One of the authors, a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist experienced in extreme and collective trauma working and doing research in the Palestinian territories for years, identified the first four participants. He selected professionals with different roles and from different territories so that their different experiences and expertise would maximize the variability of their narratives. Participants were then asked to indicate one or more contacts in their network who met the research criteria and contributed to the research. Saturation was used as a stopping criterion in data collection; interviews ended when verified that they were not adding any new relevant data (Hennink et al., 2017).

The chains of referral connecting the interviewees ensured the participants’ trust and favoured their willingness to be interviewed and positively affected the quality and depth of the data (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981).

All participants were contacted with an email presenting the objective and procedure of the research, indicating the name of the person who suggested their name and inviting those who were willing to participate in signing the attached Informed Consent.

The study involved 14 participants (N = 8 women), aged between 32 and 70 years with a mean age of 45 years (SD = 9.72) who came from the Gaza Strip, the West Bank (Ramallah, Bethlehem, Hebron and Jenin) and territories currently part of the State of Israel (Jerusalem and Jaffa). They are all mental health professionals in universities, research centres, hospitals and social welfare services. More specifically, the group consisted of three academic researchers, three psychiatrists, five psychologists, one social worker, one sociologist, and one medical anthropologist.

2.2 Ethical Considerations

Participants were voluntarily engaged in the interview and gave their verbal consent to participate in the research. Although no risks for the interviewees were identified or reported, a reflective dialogue about the use of the research findings was promoted; furthermore, risks of exploitation of such results by colonizing forces to legitimize systems of domination and subjugation were discussed. We agreed that every link to specific cases should have been anonymized and detectable places or stories made unrecognizable to preserve children’s security and integrity. The Milano-Bicocca Institutional Review Board approved the research protocol (N.368).

2.3 Data Collection

Data collection was based on semi-structured interviews in English that lasted an average of 50 min. The interviews were conducted online, leaving the respondent to choose the time of the interview and the platform of preference. The interviews were carried out from September 2020 to February 2021 by one of the authors who had expertise as a qualitative researcher and with the supervision of the first author who had expertise as a researcher and clinical psychologist in war-affected zones and, specifically, within the Palestinian context. The semi-structured interview was chosen because of the flexible structuring of the questions, which enhances information relevant to the research while maintaining semantic richness in the answers (Della Porta, 2014). Furthermore, the semi-structured interview also offers the possibility to emerge to relevant and unexpected elements thanks to freely expressing judgments, values, opinions, and past personal experiences (Della Porta, 2014).

The interview guide was developed based on the literature on the topic and the research objective. The grid was subsequently tested to verify that the questions were comprehensible and allowed to include all the topics intended to be covered. The interview was completed, and no changes to the grid were necessary, so the pilot was included in the data.

The interview introduction presented the research aim using the exact wording previously used in the inviting email participation. Care was taken not to provide definitions of the concept of agency to prevent influencing the respondent’s opinion. Next, each participant was asked for a brief description of themselves and their work to build a relationship where they could feel comfortable and free to speak.

The open-ended questions of the grid were structured according to three sub-objectives: 1. Explore the respondents’ definition of child agency (e.g. As far as you know and in your own words, how would you define child agency? Transliteration and translation of Arabic words were provided by the interviewees themselves); 2. Understand how agency’s definition relates to the specifics of the Palestinian context (e.g. Thinking of your Palestinian context and based on your experience, how do you think the agency is expressed or manifested in your society? Finally, 3. Identify ambiguous forms of children’s agency (e.g., How would you describe a child with a positive and negative agency?).

At the end of the interview, each participant was asked if he or she would like to add or elaborate on any issue that was not addressed and that he or she considered relevant to understanding the meaning of agency in the Palestinian context.

Throughout the interview, techniques were used to demonstrate attentiveness to the interlocutor and create an interpersonal situation in which he or she could speak as freely and sincerely as possible. These techniques included, for example, mirroring interventions such as echoing a keyword to encourage continuation, or putting forward a hypothesis on the meaning of what was said (e.g. I think what you meant was…) or using follow-up and clarification questions. In addition, the interviewer refrained from evaluating, rephrased potentially reactive questions, and asked for further details. The interviews were subsequently transcribed in full.

Finally, after the interviews, debriefing sections were dedicated to reflectively discussing the positioning of the interviewer and interviewees (Mortari, 2015). Namely, the interviewer, the last author of this paper, is a white woman assistant researcher who constantly was engaged with the interviewees in a conversation during the debriefing and reflective phases to question and challenge hegemonic perspectives, culturalist and essentialist interpretations, acknowledging diversity and commonalities in the interpretation of constructs and definitions crucial for the research purpose.

2.4 Data Analysis

A data-driven qualitative approach was used to guide this study as the best pathways identified to conduct an in-depth examination of key informants’ concerns, and perspectives on Palestinian children’s agency. The data analysis was conducted according to Braun and Clarke’s Thematic Analysis framework (2006). Thematic analysis is a method that does not prescribe theoretical assumptions but can be used within a critical framework. (Clarke & Braun, 2014). It is suitable for addressing different types of research questions, including, as in our study, analyzing personal and social meanings related to a topic (Clarke & Braun, 2017) The process was developed through six phases: 1) familiarisation with the data through repeated readings, which were carried out as the participants’ email responses arrived; 2) inductive generation of the initial codes by tagging and naming selections of text with the aid of N-Vivo software; 3) incorporation into themes of all codes relevant to the research question; 4) revision of the collated extracts for each theme, to consider whether they formed a coherent pattern and if the resulting themes were characterized by heterogeneity compared to the other themes; 5) final definition and nomination of the themes. A further rereading of all interviews allowed us to verify whether the identified themes were recognizable in the transcripts and ensure that all salient themes had been identified; 6) report production, selecting transcripts based on the relevance of the themes. Along the overall process, the research group discussed each code and theme. All the data were analyzed in their original language, English. Participant anonymity was protected by using code numbers.

3 Results

This section presents a themes picture extracted from TCA, while we dedicated the discussion to interpret and reflectively describe the key informants’ perspectives on children agency in Palestine.

First, several complexities related to the understanding of agency and its translation into Arabic emerged from the informants’ interviews, highlighting the absence of a univocal term to describe its core meaning. There was general concordance between the respondents in conceptualizing agency in terms of the “ability to make a choice – to have a certain extent of power over one’s life – and the ability and the willingness of using that power to obtain a specific outcome” (P1, P2, P3, P10). However, some of them problematized the possibility of exerting power and choices within the Palestinian context: “people often do not have the choice, but this does not mean they do not have agency’ (P4). Hence, the understanding of the construct was expanded, as some interviewees stated that it goes beyond an active behaviour aimed at achieving goals. Since “some people can even show agency also when they might not actively be able to do such actions, but they have the ideation.” (P8). Moreover, some respondents related the concept of agency to that of resilience (al-muruna), and thus described it as ‘the ability to adjust and protect yourself under difficult circumstances’ (P7). In contrast, others likened it more closely to sumud (steadfastness), emphasizing its oppositional and transformative aspect towards the oppression experienced (P4).

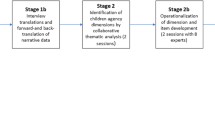

Secondly, an analysis of the concepts that emerged in the discussions with the participants resulted in a map of five themes (Fig. 1) that provided a descriptive representation of a culturally oriented conceptualization of Palestinian children’s agency. In keeping with qualitative approaches, our main goal in presenting findings was to describe the overall spectrum obtained from the content analysis, not concerning the representativeness of the opinions held (Marshall, 1996). Therefore, the first theme, A threatening context, provides a shared background to all the interviews, problematizing the achievement of a constructive agency. The second theme collects references to the Alleviating factors against the impact of the context, which are linked to a positive Healthy agency described in a third theme. On the contrary, a fourth theme gathers those Aggravating factors that generate a Harmful agency described in the last theme. The relationships between the themes are not linear but circular. They identify a pathway that goes from alleviating or aggravating factors to the determination of healthy or harmful agency; conversely, using these two different forms of actions is considered decisive in increasing resources or aggravating factors.

3.1 A Threatening Context

In this theme, we collected the discourses concerning the Palestinian context, cited by all participants as an essential component in articulating a local concept of agency. Indeed, the importance of placing the issue of agency in context and not treating it as an abstract construct taking shape in a social vacuum was stressed in all the interviews, as it is argued that the condition of occupation dramatically affects children’s capacity for agency.

So, I cannot think of another issue in the context of settler colonialism where we talk about agency in a vacuum because, in settler colonialism, my agency, my capacity to act, is inversely proportional to the price I am going to pay. (P8).

This context is described as threatening due to multiple factors grouped into two sub-themes: a dangerous environment for the integrity and safety of children and a dysfunctional environment because of lack of resources and physical space and deprivation.

Dangerousness is traced back to the Israeli occupation: for example, interviewees cite the constant presence of soldiers and their night raids, the ongoing bursting of bombs and gunfire, assaults and violence as elements that make the context unsafe, limiting children’s ability to leave the house freely, play and express themselves.

In general, children feel very insecure because soldiers come after midnight and spread fear and terror in the area. They might, for example, attack some houses, arrest some people, fire all night, bombing and firing, which make children afraid, they live in an insecure environment. (P5).

Sometimes the family limits children’s movement or the ability to play outside because of the safety of their environment. (P11).

Concerning dysfunctionality, respondents highlight the scarcity of economic resources and physical spaces such as schools, hospitals, infrastructures, and recreational spaces for children due to the permanent state of war, and they refer to many experiences of deprivation that people suffer because of the limitations imposed by the Israeli occupation:

If you interrogate children living in the camps, you will find straightforward dreams, like they just need their houses like other children; they do not have good houses or homes. They just need recreational places; they do not have any recreational places. They just need to continue their education. They just want to get married like other people, and they just want to establish some families. These are some straightforward dreams like other children. (P3).

Most children do not have the right to move because of the checkpoints because you need permission in some places to move from one place to another. If you are a child, you are under 13; you need permission. So, you cannot go without your parents, and if your parents do not have the right to have permission, you cannot move and go. Furthermore, you can understand how the children can develop themselves in isolation since they cannot go from one place to another. (P2).

According to the interviewees, the combination of these context characteristics has several negative consequences for the children’s agency, such as the destruction of their will and their inability to develop independently.

In terms of the big political picture, individuals and institutions and political bodies are losing their sense of agency because the reality is so tough, and the different lines of oppression are breaking the will of Palestinians and their beliefs in their capacity to change the reality. (P9).

3.2 Alleviating Factors

This second theme describes those resources that can mitigate the threatening context characteristics. The interviewees ‘accounts identified four types of resources: cultural and values, social, spatial, and temperamental.

The former refers to values and beliefs that can significantly influence the way children think and act. These include those characteristics of Palestinian collectivist culture such as social responsibility, responsible citizenship, the value of interpersonal relationships, education for pro-sociality and sharing a collective trauma, or culturally transmitted values such as resilience, education, and religion, which would help children to cope with daily difficulties, to provide them with a sense of hope and to attribute meaning to events.

They develop a sense of community, which means that you are a part of the community and think individually but act collectively. […] It means to enhance the individual responsibility to reach the collective goals. (P2).

There is a culture of resiliency here in Palestine. They actually try to improve their lives, and I think it is something related to Palestinian culture. Palestinian culture encourages this and tries to educate their children to be very resilient and face many economic, social difficulties. […]. (P3).

In five interviews, they also referred to the value of sumud, which means steadfastness in the wake of settler colonial and the firm determination to remain in the Palestinian homeland. The interviewees trace this value back to non-cooperation during police interrogations, and it has since been generalized and passed on as a resource for autonomy seeking, drive to action, and protection from trauma.

Now it is generalized also not just for like captivity situations, but also being able to stay in your place while they try to affect you or they surround you in the apartheid wall completely unused, stick to your land, and you choose not to leave even though they are making life a living hell for you. So, all that is seen as a form of steadfastness or sumud gives you the possibility of acting within what is possible politically. (P8).

Social factors include a safe family environment and a positive proximal environment. The former includes uncles, grandparents and cousins who often live in the same house and is characterized by supportive, protective relationships that balance limitations and self-expression. The limitations identify rules that ensure protection, psycho-physical safety, and critical thinking towards one’s actions; self-expression is described as having spaces for negotiation, confrontation, and exploration, even in the most straightforward daily actions and choices:

Some children go and throw stones at soldiers. Parents might, for example, try to protect their children from being in part in these demonstrations and drive them for their interest and security. You see, kids also prefer chocolate and other carbohydrates, and parents might struggle to convince them, for example, to replace them with better nutrition like fruits and vegetables. (P5).

Giving the children the right to present themselves and talk for themselves will allow them to develop their capacity and give them somehow the space to develop their ways in their understanding. (P2).

The positive proximal environment includes school, religious organizations, and peers when these relational contexts are characterized by listening and supportive qualities, engagement in decision-making, inclusiveness, and freedom of expression that can promote an empowered sense of agency, greater internal control, and appreciation own opinion (Veronese et al., 2015).

Sometimes the children in their life need, when they are young, the support of other members: they need support from families, school, the mosque or church, the sports class, or the community. They need all these resources to develop their internal locus of control and their ability to change. (P13).

The availability of physical spaces dedicated to children and freedom of movement also allows them to express themselves and meet their needs for play and recreation, which are deemed essential for their development. The interviewees reported these elements’ prominence because of the scarcity of possibilities discussed in the first theme.

First of all, physical space means children’s right to be outdoors and express things as much as they can under our control. […] They try to have friendly spaces, places that give children a right to play, have a playground for having their activities and develop by themselves, and be monitored by that municipality. Some municipalities have a theatre for children, and they have a library for children like Ramallah, for example. (P2).

Finally, respondents also referred to individual resources, such as awareness of the context and personal behaviour, internal control as free will and sense of responsibility, and personality characteristics such as charisma, strength, assertiveness, problem-solving ability, solidity and empathy.

A boy with a healthy agency, I would say, does not externalize responsibility. He does not put his action on others and blames others for his actions. He can plan, share his opinion and reflections, and think that his contribution matters. (P9).

For the internal environment, I intend that the person has control over his thoughts and emotions, that he has control over these things, over his desires, for example, fear. (P13).

3.3 Healthy Agency

This theme collects the participants’ narratives about a healthy agency with positive and constructive consequences for the child. It is described with various expressions, grouped into three sub-themes: resilience in the present, the constructiveness of the future and self-expression. These manifestations can be conceptually traced back to the idea of agency as resilience, a dimension that appears transversal to them. The various forms of expression of the agency are depicted as related to the threatening characteristics of the context.

Resilience in the present refers to the ability to protect oneself, cope with difficulties, maintain a sense of normality in abnormal situations, and seek a sense of control over one’s life. Such actions are often discussed in connection with the characteristics of the Palestinian context, e.g. they are directed towards the limitations of movement or the constant threat of armed soldiers.

For example, the agency could be the ability to act to protect yourself. The last possibility is the ability for children to act to protect themselves or the ability of children to act to cope with the situation or act to get out of trouble. (P7).

Agency can refer to managing daily activities despite severe mobility restrictions, checkpoints, and other things, doing ordinary things under abnormal circumstances. (P11).

Interviewees mentioned even behaviours that would be considered problematic according to a normative approach as manifestations of a healthy agency. For example, throwing stones at Israeli soldiers is perceived as a defence of one’s territory and a resilient response to oppression, rejecting the adoption of moral evaluations that do not consider the specific characteristics of the context.

For example, when one young person goes out to the checkpoint at first, and gradually others follow them and all throw stones, I mean, that you may think throwing stones at the checkpoint is something terrible, but I do not think so. I think it helps young people develop agency and respond to oppression even at the risk of being dead. (P7).

Agency as the construction of the future refers to the ability to carry out actions leading to change and to make decisions about one’s life aimed at personal growth and is closely associated with the context: change is aimed at overcoming conditions of poverty and oppression, difficult family situations or specific phenomena such as child marriages.

Sometimes we are using this terminology as an agency for change. (P2).

For example, many children who live in camps want to continue their education, improve their families’ condition, want to help their society and future and insist on education. […] You can see how much they live in difficult conditions, but they have the dream to continue their education, to be something in the future. (P3).

Finally, most respondents described agency as expressing one’s desires, tastes, opinions and emotions. It goes from choosing the clothes to buy and friends to hanging out to participate in demonstrations. This form of agency is believed to preserve good mental health despite the oppressive characteristics of the context.

I remember that there was a research at that time, where they made a comparison between the children who participated in demonstrations and the children who did not participate, and they found that the children who can express their anger and fight for human rights are much better at the level of mental health than other children. Because they feel that they can do something, they can change the environment as they can. (P13).

3.4 Aggravating Factors

The fourth theme brings together discourses on three factors that can exacerbate the negative characteristics of the Palestinian context by impacting children’s agency: a conservative patriarchal culture, a dysfunctional relational environment, and some temperamental characteristics.

Regarding the conservative patriarchal culture, most of the interviewees report that the parental style of some families is characterized by stringent external control over children, by prevaricating behaviours and restriction of their decision-making autonomy, and by not being attentive to children’s wishes and needs. These factors are perceived as further limiting children’s space for choice, action, and expression, with adverse effects on their self-esteem, sociality, and vision of the future.

The different parenting styles might create a very different social environment for the child to grow up. So, for example, you have very religious households that are conservative, and the kind of conservative thinking affects all types of decision-making in the household. How much might a child have space to negotiate in terms of decisions related to them? (P14).

When there is a bombing or war, boys can go out and respond to it, and this is agency. On the other hand, girls and women tend to be much more in distress because they do not have the social means to exercise their agency. (P4).

An additional element in this traditional cultural framework is gender stereotypes that limit girls’ ability to develop autonomously and elaborate self-aware choices. Instead, females are portrayed as docile and obedient, and the home is their designated space. This representation justifies practices such as arranged marriages, prohibitions such as sports or getting out of the house to play.

There is much more freedom to freely choose for the boys, but not for the girls, especially in the marriage issues. For example, if at 15 years old, she was forced to be married to a 30-year-old man from the same family, and she did not have any choice to say no. (P4).

Instead, the dysfunctional relational context is characterized by different forms of violence, lack of support towards children, or excessive parental permissiveness. Regarding the first aspect, the participants refer to family, school or relational settings characterized by abuse, physical, psychological, and sexual violence, aggressivity and tight restrictions. These features are associated with possible psychological, mental health and behavioural consequences in children, such as severe insecurity, anxiety, depression, fear, aggressive and harmful behaviours towards self or others.

Some children are exposed to sexual abuse and physical abuse, also emotional abuse from their families. Also, there is domestic violence, or there is a big conflict between parents and families. This situation will be harmful to the children. They will face unsafety and face aggression, violence, and neglect, leading them to behave aggressively. Also, children suffer from anxiety, depression, or fear inside the family. Also, there are many examples of violence at school: teachers behave aggressively with children. (P6).

On the other hand, lack of support refers to narratives of settings characterized by a lack of care and protection, which negatively impact children, fostering loneliness and vulnerability.

Children who are not secured in their environment and do not enjoy sufficient support are often overcome by the strength of the conflict, and it would be hard for them. (P10).

Finally, in some interviews, there were also mentions of excessively permissive parental styles that can be associated with negative consequences in children, such as exaggerated self-expression or hyperactive behaviour:

Many of the child’s problems come from the families themselves and this management. I can see many children coming with ADHD symptoms, which is not ADHD at all. It is just the manner of styling how the parents deal with their child because they give him a lot and they give him everything, and they want to avoid him what they suffered before, they want not to let him know, and that gives a child the opportunity to express himself exaggeratedly, and he will learn in the future “everything I want I will take it”.

The last sub-theme concerns a series of temperamental characteristics related to the sense of powerlessness and, on the other hand, some beliefs considered dangerous. The first one emerged concerning the perpetual alert state due to Israeli soldiers’ violence.

This situation can determine children’s passivity, withdrawal, immobility in front of dangers, and a loss of their sense of control and influence on the environment.

In the context of settler colonialism, the agency of Palestinians is constantly under attack by the Israeli security apparatus. There are many mechanisms to be set in place to intimidate, and children from a very early age have them. There is a term in Arabic, which means internalizing the oppression, the occupation, and fear of the Israeli secret service. So, they stay in check. They do not exercise any agency that might threaten Israel. (P8).

Dangerous beliefs are those of a religious nature, such as believing in the afterlife and going to heaven or hell. They can lead the child to be compliant and submissive, or on the contrary, they can be a factor in pushing the child to reckless and life-threatening actions.

When spiritual people think that it is right to be oppressed, the others will go to hell, but I will go to heaven; this is a counter-agency that makes you complaisant. (P7).

3.5 Harmful Agency

Harmful agency refers to three sub-themes: unreflective agency, destructive agency, and hyper-agency. The former is an agency characterized by reduced awareness of the consequences of one’s actions, even the dangerous ones. Thus, for example, when children reach the Israeli borders, they evade check-ins by getting into passing cars or engage in confrontations with Israeli soldiers.

There were a lot of checkpoints in the Gaza Strip in 2006 that divided the Gaza Strip into different small regions, and there was also some control by the Israeli soldiers. So, some of the children were acting recklessly of understanding the consequences. They jumped on the cars to move from one area to another, exposing themselves to dangers. (P12).

The destructive agency is attributed to children who express their emotions, desires and needs through violence, disrespect for others, and risky behaviours such as drug use or self-harm. The interviewees emphasized that this type of harmful agency is mainly present in children who have been victims of violence, trauma, economic and social humiliation, which can cause frustration, lower self-esteem, and self-assertion through deviant behaviour.

If they do not express their feelings inside the house, they will express them on an external level. It means they are very agitated; maybe they use violence more, they are aggressive more. (P10).

Hyper-agency refers to children who express themselves through disproportionate and excessive behaviour due to overconfidence in their ability to control their environment or overestimation of the effects of their actions.

In the hyper-agency, we see that he attributes too much responsibility for himself and feels inappropriate shame about his inability to meet these expectations or tries to influence reality in a way that does not respect the boundaries of others, or he does not respect the principle of self-saving. They would put their life at risk or their interest at risk. They cannot postpone their needs for the future, and they have to act immediately on it. (P9).

This outcome of hyper-agency was discussed concerning the gender stereotypes in a patriarchal culture, which attribute to males’ strength, power, authority, and the task of protecting other family members. According to the interviewees, such expectations can create in the child a disproportionate sense of his own free will, with potentially harmful actions.

If we speak about hyper-agency or like it, it is more a boy issue. […] One of the issues that we saw during the first Intifada is that many of the children saw with their eyes that their parents got humiliated, that the only way to be really strong and to be in control is to be a soldier. Moreover, that was a very terrible message that most of the children received. So, that is why if we speak about this kind of acting or hyper-agency, we see it most among boys. (P12).

4 Discussion

The present work aimed to explore a culturally informed conceptualization of child agency in ongoing violence and intractable conflict context. Hence, we sought to identify the main themes emerging from the experts’ perception of agency and its multifaceted context-specific declinations from a Palestinian perspective. Moreover, we intended to problematize and critically discuss the understanding of a Western colonizing conception of the construct, which is hegemonic in psychological and social literature (Aharoni, 2017).

4.1 Antecedents of Child Agency: What Suppress and What Enhances Agentic Behaviours in a Palestinian Context?

Our informants have widely discussed the political determinants of agentic behaviours, suppressing and enacting agency. Political oppression and military occupation forced children to construe and reinvent their everyday reality in the wake of the ongoing struggle for existence (Rijke & Van Teeffelen, 2014; Simaan, 2017). Agentivity is politically informed and influenced by internal political weakness and geographical fragmentation that jeopardize the Palestinian diasporic identity, limiting agency sources and hope for the future (Hilal, 2018). For example, internal divisions and fights have enacted a sense of insecurity and a perceived lack of freedom, diminishing individual and collective survival resources (Veronese et al., 2021a, b, c). Thus, our first theme (a threatening context) shows that all respondents stressed the importance of considering the political antecedents of the Palestinian child capability to act and react to oppressive and colonizing powers as a potential indicator of an individual/community’s sense of agency. Consequently, the experience of oppression and subjugation of Palestinian children is cognitively and emotionally overwhelming; it risks undermining people’s sense of agency, leaving them with a sense of loss and powerlessness.

Moreover, critical economic conditions and lack of resources affect children’s agency in Palestine. Poverty restricts children and adults’ opportunities and reduces sources of agency and survival, increasing a sense of hopelessness and powerlessness within the Palestinian society (Ellessi, Al Jamal, & Albaraqouni, 2019). Decades of land expropriation, eviction from homes, military control over private and public sectors diminished the colonized economy and dramatically compromised the Palestinian social capital, fueling agency sources and empowering the civil population (Dana, 2021).

Alongside political and economic determinants, respondents analyzed the patriarchal and controlling structure of the Palestinian society and the risk of oppressive internal structures and family dynamics undermining agentic competencies and capabilities among children (Hamamra, 2020). Accordingly, gender differences in children’s opportunities to develop and perform agentic behaviours have been discussed. Within the Palestinian cultures, boys are more allowed to express their agentivity as they have more freedom to do things (P4), and thus more opportunities to develop personal strategies to cope with hardships, while girls’ freedom of movement and expression are more restricted and socially controlled. Furthermore, the more girls get older, the more they must confront traditional and familial habits that inhibit individual expression of personal and social competencies out of a protective and private domestic sphere (Cavazzoni et al., 2021, b). Therefore, boys have been described as more able to make decisions regarding their lives (Bargawi, Alami, & Ziada, 2020; Medien, 2021).

Nevertheless, informants’ interviews also highlighted several resources that children can access to mitigate the impact of their threatening contexts. Indeed, individual, social, cultural, and spatial resources were all delineated as a crucial enhancer of children’s agency. For instance, it emerged in their willingness to improve their quality of life, professional and educational development to ‘be more active in their ways to change these things” (P4). Similarly, community-based and collectivist aspects of Palestinian culture were highlighted as crucial for children’s agency and well-being, conveying a sense of belonging and hope for the future (Hammack, 2011).

4.2 The Colonial Legacy of Positive and Negative Agency and some Alternatives

Respondents have stressed the non-applicability of a dichotomic western conception of negative vs positive agency (Bordonaro, 2012; Watson, 2006; Rohmann, Brailovskaia, & Bierhoff, 2019). Such a distinction could carry a conceptual bias when it applies to a Palestinian context. “I argue that the (distinction) itself is set by colonial parameters. What is positive and what is negative is decided by Israel. They are making money off this occupation by basically creating this false dichotomy and false-negative resilience or negative agency.” (P8). Such expression in a condition of ongoing occupation tends to normalize the abnormal, clearly dichotomizing excellent and destructive behaviours and pathologizing people’s attempts to react to abnormal living conditions.

Instead, as emerged from our themes, most respondents have tried to suggest the different terms of healthy or not healthy agency, agreeing on the idea that agency might also result in harmful or dangerous consequences.

On the one hand, the healthy agency was associated with behaviours and practices to protect and preserve people’s well-being. For instance, participating in the struggle for their country liberation was described as an agentic behaviour that enhanced power and control despite the threatening environment. Indeed, the concept of agency was also described as connected to the culturally valued concept of sumud (steadfastness). Grounded in national belief and religious faith (Atallah, 2017; Hammad & Tribe, 2020b), sumud is expressed through patient perseverance, enduring suffering, and remaining on the land (Hammad & Tribe, 2020b, 2021). Thus, it is closely tied to concepts such as Palestinian identity, culture, and dignity and is manifested in both individual and collective actions (Atallah, 2017; Marie, Hannigan & Jones, 2018). Agency, associated with this concept, regains positive value in the movement towards dignity, resistance, and satisfaction related to their life. From this perspective, the more people are satisfied with life, the more they develop a healthy agency (Veronese et al., 2021a, b, c, 2020a, b, 2019). Indeed, a self-perceived agentivity reduces feelings of helplessness and powerlessness and increases satisfaction with life and optimism in an environment unable to provide developmental opportunities (Veronese et al., 2021a, b, c, 2017).

On the other hand, an unhealthy agency was described as a set of harmful behaviours and activities that may put individuals’ lives or well-being in danger (e.g., facing soldiers, stealing, aggressive and violent behaviours toward others, acting recklessly). Respondents differentiate between unreflective agency, understood as action without awareness of its consequences and destructive agency intended as a violent expression of emotion, desire, or need. These behaviours seem to be activated to survive and cope with the dangerous living environment that led to a series of potentially self-destructive or dangerous consequences for the health and well-being of the individuals involved (Gigengack, 2014; Spyrou, 2018). Moreover, such agentic practices seem to be associated with feelings of despair, suffering, and helplessness (Afana et al., 2020). In so doing, the child ‘simply acts’, does not reflect or even cannot anticipate the consequences and outcomes, even if such outcomes might be hazardous. In other words, unhealthy agentic behaviours lack constructive purpose. “When we ask these adolescents, ‘ why did you go there? They said, ‘I just want to die. This is one of the bad examples, and it is a harmful one. […] There is a line between what is normal (martyrdom could be normal) and extremely reactive. It is about choices. You can ask yourself: is this action a martyr action, or is it about getting rid of life?” (P5).

The last feature of the harmful agency was described with the term hyper-agency, referring to when individuals are in the condition to take excessive responsibility. Indeed, hyper-agency emerged as the extreme of a continuum where hypo-agency, lack of decision in acting, is on the other pole. Hypo-agency can be expressed throughout passivity, feelings of helplessness and external locus of control, whilst hyper-agency is characterized by hyper-investment of responsibility that can put individuals at psychological and physical risk (Mahamid, 2020).

In sum, in a Palestinian decolonized perspective on agency, the line between what can be considered harmful or not is very tiny; on the contrary, a western perception on good and bad risk to pathologize what is normal and normalize what is abnormal, that means the real people’s living conditions (Giacaman, 2020; Harazneh et al., 2021).

Finally, as our results showed, the concept of agency emerges in its being a ‘slippery term’ (Hitlin & Elder, 2007) due to the absence of a univocal understanding of the construct. Accordingly, agency is a concept that needs to be reinterpreted and conceptualized in a way relevant to the cultural, social, and political contexts of reference. Indeed, the importance of perceiving and maintaining power over their own lives is a core issue detrimental to Palestinian existence (Veronese et al., 2020b; Simaan, 2017). Decades of colonial violence and surveillance, outlined in terms of pervasive vertical control over land, resources, sea and air-spaces, almost entirely expropriated the control of ordinary people on their lives, reducing their freedom and exploiting them from fundamental human rights (Bhungalia, 2020; Hughes, 2020). From a local perspective, agentivity is played in a politically situated environment, where the key informants consider the antecedents of the individual and collective suffering consistently dependent on politics because politically determined (Hammad & Tribe, 2020; Fassin, 2008). Therefore, agentivity is expressed throughout the will of acting and behaving to subvert oppressive structures of power (Thrope & Ahmad, 2015). Intimate and straightforward gestures inform every day relationships and reduce suffocation due to the ongoing military occupation. As a result, minimal opportunities to act are compensated by liberatory ideation, creativity and the immediacy of familiar and social relationships that foster a sense of mutuality and participation (Marshall, 2013).

Hence, from the informant’s words, the understanding of the construct of agency approaches both that of sumud and that of resilience – in its meaning as resistance and capacity to endure (al-muruna; almuqawama w alqudra ala altahamul) –, it is deployed through actions and practices, individual and collective, aimed at protecting one’s health, dignity, identity, land and connected to aspirations for the future. Agency’s conceptualization thus emerges in sharp contrast to a resilient adaptation to injustice and oppression, but it is outlined in terms of ‘the ability to act, choose and decide’ (fa’aliya; alqudra ala altasaruf w alaikhtiar w alqarar) in the direction of ‘being able to exert influence on one’s future’ (mu’ather) towards ‘change, opposition and transformation’ (alqudra ala altaa’thir ala mustaqbal almar; nahw altaghyir w almuearada w altahawul). A dynamic process embedded in daily practices and the relationship with the context. In this sense, it connotes a positive side: helping sustain and resist exposure to political violence, which helps nurture well-being in the harsh realities of life (Giacaman, 2020).

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, the Palestinian conceptualization of child agency lies in the multifaceted nature of the construct itself re-declined in a context characterized by multiple levels of complexity- cultural, political, social, economic (Wessells, 2017). Unsatisfying notions of the concept due to its western nature emphasized more individual cognitive and behavioural processes than collectivistic and community-oriented dimensions (Abebe, 2019; Ozkazanc-Pan, 2019). Furthermore, the political antecedents of the Palestinian agentivity are very weakly entailed in a Western view of agency and resilience (Hammoudeh et al., 2020; Giacaman et al., 2007). Accordingly, the conceptualizations introduced by Palestinian non-western key-informants provided social scientists with a great bunch of information about the very context-specific nature of agency and its political, social, and collective implications in environments characterized by war and colonial oppression.

Participation increased opportunities and safe-spaces for those people, including children, who seek to raise their voice against the oppressors, feeling competent and legitimate in resisting subjugating forces must inform clinical and psycho-social work throughout community-oriented liberatory interventions aimed at promoting individual and collective well-being (Makkawi, 2017; Marshall & Sousa, 2017). Overemphasis of Manichean views of ‘good and bad’ are iatrogenic in a Palestinian context, while more nuanced perspectives that consider the continuum between ‘ease and disease’ are better mirroring the complexity of the Palestinian social suffering and help in avoiding pathologizing and victimizing dynamics (Giacaman, 2018; Hammad & Tribe, 2021). The social structure of the Palestinian society is severely at risk of disruption due to decades of violence, dispossession, expulsion, and humiliation; accordingly, restoring those sources of agency and resistance can be considered a clinical must and a moral duty.

To conclude, several caveats in this pilot work must be taken into account. First, although we kept in the recruitment until the data saturation to ensure a sufficient sample’s numerosity, the relatively limited diversity of our sample in terms of geographical distribution and interviewees’ expertise could not have allowed us to grasp the complex phenomenon of child agency in Palestine fully. We can imagine that involving a more significant number of experts from other geographical areas of Palestine and the diaspora could have brought different contributions. Second, most of the respondents have been trained in Western leading academic institutions; this could have affected their view on the Western conception of the construct and directed their criticism toward the dichotomy of western vs non-western blueprints. In the future, involving the voices of experts trained in non-western academies could add any missing information.

Moreover, ethnographic studies will ensure deep knowledge of agency in Palestine as a unique context of ongoing colonial and political violence. Furthermore, additional development of this work would benefit from the possibility of interjecting, alongside the voices and conceptualizations of Palestinian experts, those of the children themselves, to take a more comprehensive look and consider differences in perspectives. Indeed, this pilot study intended to be the first step of a broader work, which aims to operationalize the construct of children’s agency within the Palestinian context (Cavazzoni et al., 2021, b; Veronese et al., 2021a, b). Through these results - integrated with children’s conceptualizations, ethnographic observations, and questionnaires administrations – the purpose is to construct a contextually and culturally sensitive instrument that detects Palestinian children’s agentic practices, as the next step of our research intent. Finally, the last limitation that would deserve a more in-depth investigation lies within the construct of agency itself. We believe that in a forthcoming study it would be crucial to explore both similarities and differences between the concept of agency (healthy and harmful) with that of coping (constructive or deconstructive), to delineate both constructs better.

Lastly, a glimpse of the researchers positioning is due. Two of them have a long-standing experience in Palestine that enforces their conviction that politics are the main drivers of Palestinian lives (Barber et al., 2014). Consequently, a political positioning of the researcher will emerge from the manuscript and somehow is necessary. That means we are fully aware of unbalancement in our language and description of the Palestinian social suffering; on the other hand, we believe that taking a position in dynamics between oppressors and oppressed, as well as including in our scientific work human rights-oriented approaches, is a professional and moral duty when researchers operate in contexts of structural violence all over the world.

References

Abebe, T. (2019). Reconceptualizing children's agency as continuum and interdependence. Social Sciences, 8(3), 81.

Afana, A. J., Tremblay, J., Ghannam, J., Ronsbo, H., & Veronese, G. (2020). Coping with trauma and adversity among Palestinians in the Gaza strip: A qualitative, culture-informed analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(12), 2031–2048.

Aharoni, S. B. (2017). Who needs the women and peace hypothesis? Rethinking modes of inquiry on gender and conflict in Israel/Palestine. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 19(3), 311–326.

Atallah, D. G. (2017). A community-based qualitative study of intergenerational resilience with Palestinian refugee families facing structural violence and historical trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry, 54(3), 357–383.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44, 1175–1184.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual review of psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 1–26). Annual Reviews, Inc..

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1, 164–180.

Bandura, A. (2017). Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Bandura, A. (2018). Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 130–136.

Barber, B. K. (2001). Political violence, social integration, and youth functioning: Palestinian youth from the intifada. Journal of Community Psychology, 29(3), 259–280.

Barber, B. K., Spellings, C., McNeely, C., Page, P. D., Giacaman, R., Arafat, C., et al. (2014). Politics drives human functioning, dignity, and quality of life. Social Science & Medicine, 122, 90–102.

Bargawi, H., Alami, R., & Ziada, H. (2020). Re-negotiating social reproduction, work and gender roles in occupied Palestine. Review of International Political Economy, 1–29.

Ben-Arieh, A., & Attar-Schwartz, S. (2013). An ecological approach to children's rights and participation: Interrelationships and correlates of rights in different ecological systems. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(1), 94.

Bhungalia, L. (2020). Laughing at power: Humor, transgression, and the politics of refusal in Palestine. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(3), 387–404.

Biernacki, P. & Waldorf, D. (1981) Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/004912418101000205

Bordonaro, L. I. (2012). Agency does not mean freedom. Cape Verdean street children and the politics of children's agency. Children's Geographies, 10(4), 413–426.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burkitt, I. (2016). Relational agency: Relational sociology, agency and interaction. European Journal of Social Theory, 19(3), 322–339.

Burton, M., & Gómez Ordóñez, L. H. (2015). Liberation psychology: Another kind of critical psychology. In I. Parker (Ed.), Handbook of critical psychology (pp. 248–255). Routledge.

Cavazzoni, F., Fiorini, A., Shoman, H., Diab, M., & Veronese, G. (2021). The role of gender and living context in shaping Palestinian children's agency and well-being. Gender, Place & Culture, 1–39.

Cavazzoni, F., Fiorini, A., Sousa, C., & Veronese, G. (2021). Agency operating within structures: A qualitative exploration of agency amongst children living in Palestine. Childhood, 28(3), 363–379.

Cavazzoni, F., Fiorini, A., & Veronese, G. (2020). Alternative ways of capturing the legacies of traumatic events: A literature review of agency of children living in countries affected by political violence and armed conflicts. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838020961878.

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. In T. Teo (Ed.), New York, Encyclopedia of critical psychology (pp. 1947–1952). Springer.

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–329.

Cummings, E. M., Merrilees, C. E., Taylor, L. K., & Mondi, C. F. (2017). Political violence, armed conflict, and youth adjustment. Springer.

Dana, T. (2021). Dominate and pacify: Contextualizing the political economy of the occupied Palestinian territories since 1967. In A. Tartir, T. Dana, & T. Seidel (Eds.), Political Economy of Palestine. Middle East Today. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68643-7_2

Della Porta, D. (Ed.). (2014). Methodological practices in social movement research. OUP Oxford.

Diab, M., Veronese, G., Jamei, Y. A., & Kagee, A. (2020). Risk and protective factors of tramadol abuse in the Gaza strip: The perspective of tramadol abusers and psychiatrists. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–17.

Durham, D. (2008). Apathy and agency: The romance of agency and youth in Botswana. Figuring the future. Globalization and the temporalities of children and youth, 151–178.

Edmonds, R. (2019). Making children's 'agency' visible: Towards the localization of a concept in theory and practice. Global Studies of Childhood, 9(3), 200–211.

Elessi, K., Aljamal, A., & Albaraqouni, L. (2019). Effects of the 10-year siege coupled with repeated wars on the psychological health and quality of life of university students in the Gaza strip: A descriptive study. The Lancet, 393, S10.

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65.

Evans, K. (2007). Concepts of bounded agency in education, work, and the personal lives of young adults. International Journal of Psychology, 42(2), 85–93.

Fassin, D. (2008). The humanitarian politics of testimony: Subjectification through trauma in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Cultural Anthropology, 23(3), 531–558.

Giacaman, R. (2018). Reframing public health in wartime: From the biomedical model to the "wounds inside". Journal of Palestine Studies, 47(2), 9–27.

Giacaman, R. (2020). Reflections on the meaning of 'resilience in the Palestinian context. Journal of Public Health, 42(3), e369–e400.

Giacaman, R., Shannon, H. S., Saab, H., Arya, N., & Boyce, W. (2007). Individual and collective exposure to political violence: Palestinian adolescents coping with conflict. The European Journal of Public Health, 17(4), 361–368.

Gigengack, R. (2008). Critical omissions: How the street children studies could address self-destructive agency. In Research with children: Perspectives and practices (2nd ed., pp. 205–219). Routledge.

Gigengack, R. (2014). Beyond discourse and competence: Science and subjugated knowledge in street children studies. The European Journal of Development Research, 26(2), 264–282.

Goodman, L. A. (1980). Snowball sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32(1), 148–170.

Habashi, J. (2011). Children's agency and Islam: Unexpected paths to solidarity. Children's Geographies, 9(2), 129–144.

Hajir, B., Clarke-Habibi, S., & Kurian, N. (2021). The 'South' speaks back: Exposing the ethical stakes of dismissing resilience in conflict-affected contexts. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 1–17.

Hamamra, B. T. (2020). The misogynist representation of women in Palestinian oral tradition: A socio-political study. Journal of Gender Studies, 29(2), 214–226.

Hammack, P. L. (2011). Narrative and the politics of meaning. Narrative Inquiry, 21(2), 311–318.

Hammad, J., & Tribe, R. (2020). Social suffering and the psychological impact of structural violence and economic oppression in an ongoing conflict setting: The Gaza strip. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(6), 1791–1810.

Hammad, J., & Tribe, R. (2020b). Adaptive coping during protracted political conflict, war and military blockade in Gaza. International Review of Psychiatry, 1–8.

Hammad, J., & Tribe, R. (2021). Culturally informed resilience in conflict settings: A literature review of Sumud in the occupied Palestinian territories. International Review of Psychiatry, 33(1–2), 132–139.

Hammoudeh, W., Kienzler, H., Meagher, K., & Giacaman, R. (2020). Social and political determinants of health in the occupied Palestine territory (oPt) during the COVID-19 pandemic: Who is responsible? BMJ Global Health, 5(9), e003683.

Harazneh, L., Hamdan-Mansour, A. M., & Ayed, A. (2021). Resiliency process and socialization among Palestinian children exposed to traumatic experience: Grounded theory approach. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 34(2), 88–95.

Hashem, R. (2014). Empirical research on gender and armed conflict: Applying narratology, intersectionality and anti-oppressive methods. SAGE Publications, Ltd.

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344

Hilal, J. (2018). The fragmentation of the Palestinian political field: Sources and ramifications. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 11(1–2), 189–216.

Hitlin, S., & Elder Jr., G. H. (2007). Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory, 25(2), 170–191.

Hoggett, P. (2001). Agency, rationality and social policy. Journal of Social Policy, 30, 37.

Howarth, C. (2006). Race as stigma: Positioning the stigmatized as agents, not objects. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16, 442–451. http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.898.

Hughes, S. S. (2020). Unbounded territoriality: Territorial control, settler colonialism, and Israel/Palestine. Settler Colonial Studies, 10(2), 216–233.

Kammerbauer, M., & Wamsler, C. (2017). Social inequality and marginalization in post-disaster recovery: Challenging the consensus? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 24, 411–418.

Klocker, N. (2007). An example of 'thin' agency: Child domestic workers in Tanzania. In: Global perspectives on rural childhood and youth. 100–111. Routledge.

Kuus, M. (2019). Political geography I: Agency. Progress in Human Geography, 43(1), 163–171.

Landes, S. D., & Settersten Jr., R. A. (2019). The inseparability of human agency and linked lives. Advances in Life Course Research, 42, 100306.

Levey, E. J., Laird, L. D., Becker, A. E., Harris, B. L., Lekpeh, G. G., Oppenheim, C. E., Henderson, D. C., & Borba, C. P. (2018). Narratives of agency and capability from two adolescent girls in post-conflict Liberia. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 42(4), 947–979.

Lokot, M., Sulaiman, M., Bhatia, A., Horanieh, N., & Cislaghi, B. (2021). Conceptualizing "agency" within child marriage: Implications for research and practice. Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105086.

Mahamid, F. A. (2020). Collective trauma quality of life and resilience in narratives of third generation Palestinian refugee children. Child Indicators Research, 13(6), 2181–2204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09739-3

Majumder, S. (2021). Anthropological theories I: Structure and agency. The SAGE handbook of Cultural Anthropology, 159.

Makkawi, I. (2017). The rise and fall of academic community psychology in Palestine and the way forward. South Africa Journal of Psychology, 47(4), 482–492.

Marie, M., Hannigan, B., & Jones, A. (2018). Social ecology of resilience and Sumud of Palestinians. Health, 22(1), 20–35.

Marshall, M. N. (1996). The key informant technique. Family Practice, 13, 92–97.

Marshall, D. J. (2013). 'All the beautiful things': Trauma, aesthetics and the politics of Palestinian childhood. Space and Polity, 17(1), 53–73.

Marshall, D. J., & Sousa, C. (2017). Decolonizing trauma: Liberation psychology and childhood trauma in Palestine. Conflict, Violence and Peace, 11, 287.

Martín-Baró, I. (1994). Writings for a liberation psychology. Harvard University Press.

Medien, K. (2021). Israeli settler colonialism, "humanitarian warfare," and sexual violence in Palestine. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 1–22.

Mizen, P., & Ofosu-Kusi, Y. (2013). Agency as vulnerability: Accounting for children's movement to the streets of Accra. The Sociological Review, 61(2), 363–382.

Mortari, L. (2015). Reflectivity in Research Practice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 14(5). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915618045

Nguyen-Gillham, V., Giacaman, R., Naser, G., & Boyce, W. (2008). Normalizing the abnormal: Palestinian youth and the contradictions of resilience in protracted conflict. Health & Social Care in the Community, 16(3), 291–298.

Olsson, L., Jerneck, A., Thoren, H., Persson, J., & O'Byrne, D. (2015). Why resilience is unappealing to social science: Theoretical and empirical investigations of the scientific use of resilience. Science Advances, 1(4), e1400217.

Otto, I. M., Wiedermann, M., Cremades, R., Donges, J. F., Auer, C., & Lucht, W. (2020). Human agency in the Anthropocene. Ecological Economics, 167, 106463.

Ozkazanc-Pan, B. (2019). On agency and empowerment in a# MeToo world. Gender, Work and Organization, 26(8), 1212–1220.

Pham, L. (2019). Sen-Bourdieu framework: Conceptualizing normative agency. In International graduates returning to Vietnam (pp. 39–55). Springer, Singapore.

Prout, A., & James, A. (1997). Re-presenting childhood: Time and transition in the study of childhood. Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood (pp. 230–250). Routledge.

Qouta, S., Punamäki, R. L., Miller, T., & El-Sarraj, E. (2008). Does war beget child aggression? Military violence, gender, age and aggressive behavior in two Palestinian samples. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 34(3), 231–244.

Rijke, A., & Van Teeffelen, T. (2014). To exist is to resist: Sumud, heroism, and the everyday. Jerusalem Quarterly, 59, 86.

Rohmann, E., Brailovskaia, J., & Bierhoff, H. W. (2019). The framework of self-esteem: Narcissistic subtypes, positive/negative agency, and self-evaluation. Current Psychology, 1–8.

Rudnick, L., & Boromisza-Habashi, D. (2017). The emergence of a local strategies approach to human security. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 12(4), 382–398.

Ryan, C. (2015). Bodies, power and resistance in the Middle East: Experiences of subjectification in the occupied Palestinian territories. Routledge.

Shanahan, M. J., & Hood, K. E. (2000). Adolescents in changing social structures: Bounded agency in life course perspective. Negotiating adolescence in times of social change, 123–134.

Simaan, J. (2017). Olive growing in Palestine: A decolonial ethnographic study of collective daily-forms-of-resistance. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(4), 510–523.

Spyrou, S. (2018). Disclosing childhoods. In Disclosing childhoods (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan.

Stewart, D. L. (2021). Performing goodness in qualitative research methods. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2021.1962560.

Swann Jr., W. B., & Jetten, J. (2017). Restoring agency to the human actor. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(3), 382–399.

Thompson, A. C. (2019). Vulnerable agents: Obscured vulnerability and exaggerated agency in Mexican migrant children. Doctoral dissertation.

Thorpe, H., & Ahmad, N. (2015). Youth, action sports and political agency in the Middle East: Lessons from a grassroots parkour group in Gaza. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(6), 678–704.

Veronese, G., Pepe, A., Jaradah, A., Murannak, F., Hamdouna H. (2015). Quality of Life and Determinants of Parents’ School Satisfaction in War Contexts. SAGE Open 5(4) 215824401560842. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015608422.

Veronese, G., Pepe, A., Jaradah, A., Murannak, F., & Hamdouna, H. (2017). "we must cooperate with one another against the enemy": Agency and activism in school-aged children as protective factors against ongoing war trauma and political violence in the Gaza strip. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 364–376.

Veronese, G., Pepe, A., Cavazzoni, F., Obaid, H., & Perez, J. (2019). Agency via life satisfaction as a protective factor from cumulative trauma and emotional distress among Bedouin children in Palestine. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1674.

Veronese, G., Pepe, A., Obaid, H., Cavazzoni, F., & Perez, J. (2020a). Agency and life satisfaction in Bedouin children exposed to conditions of chronic stress and military violence: A two-wave longitudinal study in Palestine. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25(1), 242–259.

Veronese, G., Sousa, C., Cavazzoni, F., & Shoman, H. (2020b). Spatial agency as a source of resistance and resilience among Palestinian children living in Dheisheh refugee camp, Palestine. Health & Place, 62, 102304.

Veronese, G., Cavazzoni, F., Jaradah, A., Yaghi, S., Obaid, H., & Kittaneh, H. (2021a). Palestinian children living amidst political and military violence deploy active protection strategies against psychological trauma: How agency can mitigate traumatic stress via life satisfaction. Journal of Child Health Care. Published ahead of print on May 13. https://doi.org/10.1177/13674935211017727

Veronese, G., Diab, M., Abu Jamei, Y., Saleh, S., & Kagee, A. (2021b). Risk and protection of suicidal behavior among Palestinian University students in the Gaza strip: An exploratory study in a context of military violence. International Journal of Mental Health, 1–18.

Veronese, G., Pepe, A., Cavazzoni, F., Obaid, H., & Yaghi, S. (2021c). Measuring agency in children: The development and validation of the war child agency assessment scale - Palestinian version (WCAAS-pal). Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02449-1

Wessells, M. G. (2017). Children and armed conflict: Interventions for supporting war-affected children. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 23(1), 4.

Watson, A. M. (2006). Children and international relations: A new site of knowledge? Review of International Studies, 237–250.

Availability of Data and Material

data is not available for confidentiality reasons.

Code Availability

N/A

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GV planned the research, designed the methods, revised analysis and wrote the article; LM planned the methods, revised the analysis and wrote the article; FC wrote the article; DM did the interviews, transcribed the materials, did the text analysis and revised the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

All authors do not have competing interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

the research has been approved by the Institutional review board at the University of Milano-Bicocca.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions