Abstract

Although various reviews about leadership development (LD) have been published in recent years, no one has attempted to systematically review longitudinal LD studies, which is arguably the most appropriate way to study LD (Day, Leadership Quarterly, 22(3), 561–571, 2011). In this way, the focus of the present scoping review is to understand how true longitudinal LD studies have been investigated and what inconsistencies exist, primarily from a methodological perspective. Only business contexts and leadership-associated outcomes are considered. To achieve this, ample searches were performed in five online databases from 1900 to 2021 that returned 1023 articles after the removal of duplicates. Additionally, subject experts were consulted, reference lists of key studies were cross-checked, and handsearch of leading leadership journals was performed. A subsequent and rigorous inclusion process narrowed the sample down to 19 articles. The combined sample contains 2,776 participants (67% male) and 88 waves of data (average of 4.2). Evidence is mapped according to participants, setting, procedures, outcomes, analytical approach, and key findings. Despite many strengths, a lack of context diversity and qualitative designs are noticed. A thematic analysis indicates that LD authors are focused on measuring status, behavioral, and cognitive aspects. Implications for knowledge and future research paths are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Even though many literature reviews about leadership development (LD) have been published in recent years (e.g., Vogel, Reichard, Batistic, & Cerne, 2020; Lacerenza et al., 2017; Day et al., 2014), no one has attempted to systematically review longitudinal LD studies, let alone true longitudinal studies, which is arguably the most appropriate way to study LD (Day, 2011). True longitudinal is operationalized in the present study as research involving three or more phases of data collection (Ployhart & Vandenberg, 2010), since pretest-posttest designs can be limited when it comes to measuring change (Rogosa et al., 1982). In addition to the focus on studies using multiple waves of data, the particular interest here is in the underlying methodological choices of those studies. The goal is not only to map elements such as concepts, strategy, participants, settings, analytical approaches and tools, but also to make gaps and inconsistencies more evident in the hope of advancing the science of LD.

The current study relies on the assumption that longitudinal methods are the most appropriate way to study LD as the field was categorized as “inherently longitudinal” (Day, 2011). These arguments are partly motivated by the idea that the leader development process is an ongoing and lifelong journey (Day et al., 2009), which, in turn, indicates why cross-sectional methods would be less suited. By inspecting the term “leadership development”, it is noted that it refers not only to the science of leadership, but also the science of development, which is concerned with measuring change over time. The development side is underexplored, but the focus should be on both parts of the equation (Day et al., 2014). As Day (2024) recently puts it: “We need a separate field of leader and leadership development apart from the voluminous leadership literature because of the development component” (p. 213). Despite referring to leadership and development as a science above, it seems worth acknowledging that they can be seen as an art too (Ladkin & Taylor, 2010). The art of leadership is described by Springborg (2010) as staying present with one’s senses instead of quickly jumping to conclusions. This line of thinking suggests that practicing the art of leadership means relying on intuition, awareness, and feeling. This is potentially relevant as the complexity of the world cannot be completely understood from scientific operationalizations alone, arts-based practices relate differently with complexity, allowing novel ways of responding to it (Ladkin & Taylor, 2010).

Considering the preceding paragraphs, the present research question can be expressed as: how are true longitudinal studies of LD being investigated and what inconsistencies exist, primarily from a methodological perspective? To help answer this question, a scoping review was chosen, a type of systematic review that is most suitable when the goal is to map evidence and identify gaps in knowledge (Tricco et al., 2018), and not to understand the effectiveness of specific interventions, which is the job of a traditional systematic review (Munn et al., 2018). Researchers suggest that scoping reviews should be as comprehensive as possible (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005), thus the process of including articles involved searching multiple online databases, identifying gray literature, cross-checking reference lists of key studies, and handsearching leading leadership journals. Only articles written in English language were admitted. Significant time was spent building a subsequent search strategy and a pre-determined inclusion criteria was followed to arrive at the final sample. The search and inclusion process follows the procedures of the PRISMA statement, the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (Moher et al., 2009), and particularly the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018).

Nineteen studies were further analyzed out of 1,236 identified. A large table (Table 1) is presented in the results section mapping the most important methodological information. As recommended (Tricco et al., 2018), a thematic analysis is conducted too, followed by a discussion about the emergent themes in longitudinal LD.

Literature review

Leader and leadership development

Using 2,390 primary works and 78,178 secondary ones, a recent bibliometric review (Vogel et al., 2020) maps the LD field in two interesting ways: through a historiography and a co-citation analysis. Historiography indicates that LD originated in actual organizational challenges and needs around 1989 and then transitioned to theory building around 2004 pulled by authentic leadership development scholars. The co-citation analysis indicates that seminal theories in leadership, motivation and learning highly influenced the field, which, in turn, shifted its focus to developmental interventions and processes as well as theoretical frameworks and intra-person developmental efforts such as identity construction (Vogel et al., 2020). Still on a broader level, by reviewing 25 years of LD contributions, Day et al. (2014) explains why LD is young compared to the centenary field of leadership. The former is, by definition, interested in change (development), and the latter, for a significant time of history, has focused on traits, which are harder to change, though not impossible (Bleidorn et al., 2019).

Individuals have predisposed levels of leadership ability (Arvey et al., 2007) and researchers have been especially interested in intelligence (Judge et al., 2004) and personality (Judge et al., 2002). Even though genetics will always play a part, leadership training works even more than previously thought regarding reactions, learning, transfer, and actual results, as shown by a meta-analysis (Lacerenza et al., 2017).

Instead of training, McCall (2004) argues that experiences are at the heart of LD. The challenges associated with experiences is that it is not simple to offer the right experiences to the right executives and that they vary in developmental potential due to contextual circumstances and individual differences. Six years later, McCall (2010) reinforces his argument, suggesting that companies should bet on what is potentially the most powerful developer of leaders: experience. Within the scope of experiences, some scholars are making the case for “consciousness-raising experiences” in leadership development (Mirvis, 2008). They are designed for the mind and heart and characterized by the focus on self, others, and society. Another relevant and more common type of experience in life is education. Evidence from almost half a million students from 600 institutions highlights that leadership knowledge as well as opportunities for application of learned principles are related with an increase in leadership capacity upon conclusion of higher education (Johnson & Routon, 2024).

Experiences and trainings are naturally more focused on developing skills and competencies, but some authors understand that these sometimes loosely connected leadership skills should be integrated to a leader identity (Lord & Hall, 2005). Indeed, identity has become a more popular aspect of LD (Epitropaki et al., 2017) and empirical investigations claim that leader identity is associated with leader effectiveness (Day & Sin, 2011).

Day (2000) makes the important distinction between leader development (developing individuals) and leadership development (developing the collective). In the present work, the use of “LD” incorporates both leader and leadership development. Drawing on this idea, The Center for Creative Leadership defines leader development as “the expansion of a person’s capacity to be effective in leadership roles and processes (Van Velsor et al., 2010, p. 2)” and leadership development as “the expansion of a collective’s capacity to produce direction, alignment, and commitment (Van Velsor et al., 2010, p. 20)”. Respecting these distinctions and contributions, Day and Dragoni (2015) review theoretical and practical arguments and suggest proximal and distal outcomes to indicate whether leadership is developing from an individual level and a team level. For instance, on the individual level, leadership self-efficacy and leader identity are proximal indicators while dynamic skills and meaning-making structures are distal. Regarding the team level, psychological safety and team learning are proximal indicators while collective leadership capacity are distal ones.

LD is also greatly associated with mentoring across publications, for instance, it increases leadership self-efficacy, which, in turn, predicts leader performance (Lester et al., 2011), and it also promotes the development of a leader identity (Muir, 2014). Interestingly, the effect of mentoring is not only beneficial to mentees in terms of developing (transformational) leadership, but also to mentors (Chun et al., 2012). Similarly, a recent study shows that mentors can develop their leader identity and self-efficacy as a result of a mentoring process (Ayoobzadeh & Boies, 2020). In the same vein, coaching has been established as an important LD topic (Day, 2000). A systematic review shows several methodological challenges associated with executive coaching, but list many evidence-based benefits of the practice in relation to the coachee (e.g. better leadership skills), the organization, and the coach (Athanasopoulou & Dopson, 2018).

Feedback seems to be another popular theme within the LD literature, especially 360-degree feedback (Atwater & Waldman, 1998), a practice associated with enhanced management competence in corporate environments (Bailey & Fletcher, 2002). Within an MBA context, peer feedback decreased self-ratings of leadership competence three and six months later, an effect that was stronger for women than men, suggesting that women align their self-ratings with peer ratings while men have a tendency to inflate their self-images (Mayo et al., 2012). Seifert and Yukl (2010) contribute to the literature by demonstrating that two feedback interventions enhance leader effectiveness compared to only one intervention. Even though a recent meta-analysis related the use of 360-degree feedback during leadership training to higher results compared to single-source feedback, it is also linked to lower levels of learning and transfer (Lacerenza et al., 2017). For example, receiving negative feedback from multiple sources could obstruct improvement because it may threaten one’s self-view. These results can be considered thought provoking given how 360 feedback is popular and sometimes taken for granted by organizations.

Longitudinal research

Despite some very early records of longitudinal research overviewing the history and the fundamentals of this methodology, Rajulton (2001) says that it was not until the 1920s that more significant longitudinal studies started to be found, allowing the science of development and growth to be advanced.

An early definition of longitudinal research is given by Baltes (1968), he contrasts longitudinal and cross-sectional research and defines the former as observing one sample at different measurement points (pp. 146–147). Ployhart and Vandenberg (2010) take a step back, they discern between the terms static and dynamic before attempting to define longitudinal research, they relate the former with cross-sectional methods and the latter with longitudinal ones. Similarly, Rajulton (2001) states that cross-sectional information is concerned with status, and longitudinal information deals with progress and change in status.

However, one interesting definition offered by Taris (2000) is that longitudinal research happens when “data are collected for the same set of research units for (but not necessarily at) two or more occasions, in principle allowing for intra-individual comparison across time” (pp. 1–2). Additionally, Ployhart and Vandenberg (2010) focus on the quantity of observations when they say that longitudinal research is “research emphasizing the study of change and containing at minimum three repeated observations (although more than three is better) on at least one of the substantive constructs of interest” (p. 97). Acknowledging the two previous definitions and its weaknesses, Wang et al. (2017) argue that longitudinal research is not necessarily focused on intra-individual analysis and cite examples where two waves of data collection is an appropriate procedure (e.g., prospective design), thus claiming an alternative definition: “longitudinal research is simply research where data are collected over a meaningful span of time” (p. 3).

Although definitions and tools seem to be improving in the past years, it was not always like this. Reflecting on the challenging past decades for the reliability of longitudinal research, particularly the 1960s and 1970s, Singer and Willett (2003) said that although scientists had always been fascinated with the study of change, it was only after the 1980s that the subject could be studied well due to new methodological tools and models developed.

Given the analytical problems at the time, Rogosa et al. (1982) clarifies misconceptions about measuring change, especially in terms of the pretest-posttest design, and encourage researchers to use multiple waves of data. They claim that “two waves of data are better than one, but not much better” (p. 744). Contrary to the thinking expressed in previous decades, Rogosa and Willett (1983) demonstrate the reliability of difference scores, which are typically used in two-wave designs, in the measurement of change for some cases (e.g., individual growth), though they do not claim the score to have high reliability in general.

Coming from an education and psychological perspective, Willett (1989) demonstrates that significant increases in the reliability of individual growth measures can be harnessed by incrementing data collection with a few additional waves of information beyond two. Aware of the methodological problems and the current conversation, Chan (1998) proposed an integrative approach to analyze change focused on the organizational context embodying longitudinal mean and covariance structures analysis (LMACS) and multiple indicator latent growth modeling (MLGM). He expressed his ideas in a less technical way, which facilitated the progress of the field.

Ployhart and Vandenberg (2010) raise key theoretical, methodological, and analytical questions when it comes to developing and evaluating longitudinal research in management. And using a panel discussion format, Wang et al. (2017) build on the same structure with the purpose of helping researchers make informed decisions in a non-technical way.

Longitudinal leadership development research

A pioneer initiative of longitudinal LD studies is the Management Progress Study (MPS) initiated by the Bell System (AT&T) in 1956 with the purpose of analyzing the growth, mostly in terms of status, of 422 men (Bray, 1964). Interesting follow ups were conducted after 8 and 20 years making this project one of the most popular field researches in management development (Day, 2011).

Attempting to longitudinally analyze a new generation of executives in 1977, A. Howard and D. Bray launched the Management Continuity Study (MCS). This ambitious project replicates many aspects of the MPS, but it also addresses weaknesses such as the lack of representation of women and different ethnicities (Howard & Bray, 1988). The MCS sample was used by many other longitudinal scholars to obtain stimulating insights, for instance, how successful male and female executives deal with power (Jacobs & McClelland, 1994), and the influence of college experiences on progress and performance (Howard, 1986).

In parallel with these two major longitudinal efforts, an Eastern perspective contributes significantly to the field of longitudinal LD. The Japanese Career Progress Study originated in 1972 is a sample of 85 male college graduates starting their careers at a leading Japanese department store chain who were followed up after 7 years (Wakabayashi & Graen, 1984) and 13 years (Wakabayashi et al., 1988) mostly in terms of promotion, salary, and performance. The multilevel and mixed-method approach with multiple waves of data revealed, in aggregation, that the organizational assessment of management potential of newcomers, the quality of exchange with superiors, and their early job performance predicted speed of promotion, total annual salary, and annual bonus on the seventh and thirteenth year of tenure. Wakabayashi et al. (1988), in a summarizing tone, state that the first three years of employment are critical when it comes to later career progress and leadership status up to 13 years.

After these pioneers, more LD longitudinal works started to emerge. Perhaps the biggest contribution to the area is the publication of a special issue in 2011 by the Leadership Quarterly. Authors of the referred issue promote important discussions and advance thought-provoking insights. In particular, the importance of true longitudinal studies, the ones involving three of more waves of data collection (Day, 2011), as well as the benefits of analyzing leadership through a long-lens approach (Murphy & Johnson, 2011). Specifically, the special issue explored childhood and adolescence factors. For instance, Gottfried et al. (2011) studied the motivational roots of leadership and found that children and teenagers with higher academic intrinsic motivation are more likely to want to lead as adults. Similarly, Guerin et al. (2011) found that adolescent extraversion predicts leadership potential over a decade later in adulthood with the relationship being fully mediated by adult social skills. Furthermore, the special issue explored family aspects in relation to LD. Oliver et al. (2011) are the first to connect family environment in childhood to adulthood leadership. Specifically, they found that a supportive and stimulating family atmosphere led to transformational leadership qualities in adulthood through positive self-concept. Li et al. (2011) detected that higher family socioeconomic status negatively influences leader advancement for females. The opposite was observed for males.

Apart from the larger longitudinal efforts mentioned above, many independent LD studies that rely on their own longitudinal samples contributed significantly to the field too. They vary greatly in settings and concepts, but some early important contributions seem to be Atwater et al.‘s (1999) demonstration that military leader emergence and leader effectiveness can be predicted by individual differences such as cognitive ability, physical fitness, and prior influence experience. Focused on the followers instead of the leaders, Dvir et al. (2002) suggest that transformational leadership training leads to followers’ development and performance. Also, executives’ competence, judged by self and others, significantly improves after multi-rater multi-source feedback (Bailey & Fletcher, 2002).

Other notable contributions involve the influence of self-regulation training on LD (Yeow & Martin, 2013), mentoring as a tool to develop not only the mentee (Lester et al., 2011), but also the mentor (Chun et al., 2012), and more unorthodox views such as dark personality traits and performance (Harms et al., 2011). However, some authors seem to be not only focused on behavioral, but also cognitive change (e.g., leader identity). Day and Sin (2011) claim that individuals with a strong leader identity are more effective across time. By using a university sample, Miscenko et al. (2017) propose that leader identity develops in a J-shaped pattern and that leader identity development is associated with leadership skills development. On the other hand, high-potential executives seem to develop leader identity in a linear and progressive way (Kragt & Day, 2020).

Methodology

Type of review and sources of evidence

Despite being more widely seen, systematic reviews are best suited to approach specific questions addressing effectiveness, appropriateness, meaningfulness, and feasibility of particular interventions (Munn et al., 2018), and given this study’s broader research question, a scoping review was chosen. This method is usually defined as a mapping process (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) or a system for synthesizing evidence (Levac et al., 2010). More recently, it was described as a “systematic way to map evidence on a topic and identify main concepts, theories, sources, and knowledge gaps” (Tricco et al., 2018, p. 467). Despite the differences, both types of reviews are quite related, Moher et al. (2015) even see them as part of the same “family”.

The execution of each step of the current review was guided by the methodology initially laid out by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and by the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and its corresponding checklist (Tricco et al., 2018). Following recommendations that a scoping review should be as comprehensive as possible (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005), different sources were used: (1) Online databases were searched (e.g., Web of Science, Scopus); (2) gray literature was identified (e.g., subject experts were consulted); (3) reference lists of key studies were cross-checked; and (4) handsearch of leading leadership journals was performed.

Search strategy for online databases: building search strings and identifying databases

Significant time was spent building the search strings for the present work as this is seen as a wise choice to improve search efficiency (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009). According to Arksey and O’Malley (2005) the process starts by having the research question in mind and identifying the key concepts that are present, in this case, longitudinal, leadership, and development. Based on this initial process, synonyms for each concept were identified. For instance, since the term “leadership” can be often substituted in the literature by management, executive, supervisory, and potentially others, these variations were added to the search string. Similarly, the term “development” can be substituted by training, program, intervention, and potentially others, thus these variations were incorporated as well.

In addition to identifying synonyms, this search strategy took into consideration some other concepts that seem to be highly associated with LD such as coaching, mentoring, and 360-feedback (Day, 2000). Hence, these terms plus their variations were incorporated. Finally, the search strategies and the specific keywords of past LD systematic reviews were screened (e.g. Collins & Holton, 2004; Lacerenza et al., 2017; Vogel et al., 2020) to verify any potential blind spots concerning the terms to be used here. In practical terms, seven different search strings were necessary to capture the process described. The first search string is completely detailed as follows and the remaining search strings are available in Appendix A.

Search 1: longitudinal AND (“leader* development” OR “manage* development” OR “executive development” OR “supervisory development” OR “team development” OR “human resource$ development”).

The search strategy and the definition of keywords were verified by a professional librarian at ISEG – University of Lisbon. Feedback and other suggestions were given over a one-hour videocall in March of 2021.

One additional decision when it comes to the search strategy is identifying the databases to be used. Systematic review guidelines seem confident that authors must search more than one database (Liberati et al., 2009), others generally suggest that two or more are enough (Petticrew & Roberts, 2008), but little guidance is available for precisely deciding when to stop the searches, especially in the context of scoping reviews in social sciences instead of systematic reviews in medical sciences (e.g., Chilcott et al., 2003).

Considering this situation, searches started in a highly ambitious way in terms of quantity of databases and search restrictions (e.g., filters), and were iteratively pondered according to the reality of executing the work given the colossal volume of data for two authors with limited resources to go through. The described strategy seems aligned with both earlier (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) and more recent recommendations (Peters et al., 2020) for authors writing scoping reviews as it is thought that comprehensiveness should be framed within the constraints of time and resources available to the authors. In this way, five databases were used: Web of Science, PsycARTICLES, Ebsco’s Business Source Complete, JSTOR, and Elsevier’s Scopus. The databases were mostly hand curated based on relevancy for LD. In other words, WoS has been extensively used by authors published in high-caliber leadership journals such as the Leadership Quarterly, and on some cases it is the only source of information (Vogel et al., 2020). PsycARTICLES seems unavoidable in psychological research, and it is found in most reviews at top-ranked journals interested in LD such as the Journal of Applied Psychology, for instance. Business Source Complete, Scopus, and JSTOR went through a similar curation process in addition to being well-known and comprehensive sources of information across social sciences disciplines.

Inclusion criteria

Three essential criteria served as pre-requisites for document inclusion in light of the research question.

-

Method: Is it a true longitudinal study (three or more waves of data) as opposed to a cross-sectional or a pretest-posttest one?

-

Context: Is the work approaching a business context? This study is interested in understanding longitudinal contributions to LD within a “business context”, which is an umbrella term created to incorporate for-profit and nonprofit companies, public organizations, and graduate students associated with management (e.g., MBA, executive education) or closely related areas (e.g., economics, organizational psychology). In this way, numerous LD studies involving sports, healthcare, and military contexts were naturally excluded from the final sample.

-

Concepts and measures: Is the study actually measuring change in terms of LD? Only results incorporating LD as a primary variable were considered. In this way, the authors were interested in analyzing leadership-related outcomes (e.g., leadership efficacy, leader identity), and not more distant concepts (e.g., job performance).

Only documents from 1900 until 2021 in English language were considered. Even though LD was not a formal research area in the early or mid-1900s, when the field “all years” is selected before a search in most databases, the range set by default starts in 1900. For clarification purposes, the earliest study analyzed in the present work dates to 1986.

On a more technical note, different filters according to the database at hand were used to refine the results (e.g., subject area, document type). As an example, the present research is not interested in LD in the sports space or document types such as editorials or reviews, thus filters were used to aid this refinement process. This whole procedure is consistent with the idea proposed by Levac et al. (2010) that the inclusion and exclusion criteria should be iterative and adapted based on the challenges identified.

Additional sources of information

Almost all the way through the screening execution, the authors of this study learned that scoping review researchers are encouraged to explore other sources of information apart from databases (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Peters et al., 2020). As a result, three à posteriori procedures were used to add evidence: (1) identifying gray literature through contacting subject experts, (2) cross-checking reference lists of important studies, and (3) handsearching key bibliographies and journals. Although the standard procedure for systematic reviews is to include articles from additional sources before the start of the screening process (Liberati et al., 2009), it is believed that the inverted execution does not threat the soundness of this work since adding and subtracting results before or after cannot affect the final sum and considering the iterative nature of scoping reviews (Levac et al., 2010). The only unfortunate implication observed was an extra load of work given the necessity to do an additional round of screening instead of screening all in once.

When it comes to consulting subject-matter experts, a list of a dozen high-level names was put together (e.g., D. Day, J. Antonakis, C. Lacerenza, L. Dragoni, R. Reichard) and the individual email outreach was executed in June of 2022. The email text to the list of authors included a brief personal introduction, the reason for contact and descriptions of the request, and a gratitude note for the impact of their work on this author’s academic journey.

Despite some prompt and friendly replies from high-caliber authors, including D. Day, who is considered a seminal scholar in LD, and also J. Antonakis, who was the chief editor of the Leadership Quarterly journal at the time of contact, no gray documents could have been added for multiple reasons varying from email bounces, no replies, replies from authors with no suggestions in mind, or irrelevant suggestions for this particular research question.

In addition to the step above, reference lists of key studies were cross-checked. First, pivotal review studies in LD (e.g., Day et al., 2014; Lacerenza et al., 2017) had their reference lists analyzed. Then, selected articles were further evaluated and selected based on screening of title, keywords, abstracts, and, ultimately, full-text analysis.

Finally, handsearching, a legitimate process in systematic literature reviews (Liberati et al., 2009), including scoping reviews (Tricco et al., 2018), was performed. Eight journals labeled “dominant” based on a co-citation analysis of LD (Vogel et al., 2020) were handsearched as an additional attempt to locate relevant evidence. The Academy of Management Review was part of this list, but naturally excluded from this process as no empirical works would have been found there, so the seven journals analyzed were Leadership Quarterly, Journal of Applied Psychology, Academy of Management Learning & Education, Personnel Psychology, Leadership, Journal of Organizational Behavior, and Journal of Management.

In terms of execution, central terms for the present research question (e.g., leadership development, longitudinal) were typed into the general search boxes of these journals and the list of results were scanned. Documents indicating good fit were further analyzed via screening of abstract and keywords, and full text. When searching the Leadership Quarterly journal, particular attention was devoted to a special issue published in 2011 centered on longitudinal leadership development studies (volume 22, issue 3). The handsearch process generated results as two articles that would not have been found otherwise were included in the sample for respecting the determined criteria (Cherniss et al., 2010; Dragoni et al., 2014).

Data charting process

Referred to as “data extraction” in systematic reviews, data charting (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) is the process of extracting information from the sample in a scoping review. Even though any information can be charted in practice, researchers ideally should obtain pieces of information that help answer the research question (Levac et al., 2010). Given this ponderation and the research question at hand, a data charting framework was created to keep a consistent extraction standard across studies.

-

Nature of variables (e.g., quantitative, qualitative).

-

Research strategy (e.g., experiment, survey).

-

Participants (e.g., sample size, gender distribution).

-

Setting (e.g., industry, company information).

-

Intervention (e.g., program characteristics).

-

Research procedures (e.g., comparator, waves of data).

-

Outcome measures (e.g., variables, instruments).

-

Analytical approach (e.g., strategy, techniques).

Despite the primary focus on methodological choices of longitudinal LD studies, it was judged important to also chart the key findings of each study given the underlying motivation of the present research to contribute to the longitudinal LD field. A separate table (Table 2) was created to map this information. The data charting process took place with the assistance of Microsoft Excel.

Results

Search results

Taking into consideration the search strategy and the inclusion criteria described previously, the WoS database returned 673 results. PsycARTICLES, in turn, retrieved 84 results. Next, Ebsco’s Business Source Complete returned 332 documents. JSTOR found 49 articles. Lastly, Elsevier’s Scopus retrieved 98 results. In total, 1236 documents were found. After removal of duplicates, a total of 1023 articles were screened given the determined criteria. The screening of titles, abstracts, and keywords removed 810 works, and screening the full text removed another 196 works, resulting in 17 included studies. À posteriori inclusion based on conversations with LD experts and handsearch of bibliographies and journals added another two documents, confirming a final sample of 19 articles. This whole process is illustrated by the flow chart below (Fig. 1).

General characteristics

The table listing the 19 documents and some of their basic characteristics can be found in Appendix B. The works comprise different years, journals, countries, and authors. The first true longitudinal study of LD in a business context was published in 1986 by the Journal of Applied Psychology. One noticeable feature of the table found in Appendix B is the substantial 22-year gap in publications from 1988 to 2010. After 2010, on the other hand, researchers seem to have found more efficient ways to collect longitudinal data, and until 2021, on average 1.42 studies were published every year. Despite the progress, compared to past decades, the number is still quite modest given the importance of true longitudinal studies to the science of LD (Day, 2011).

In terms of outlets, eleven different journals represent the sample. The pioneer on the subject and methodology is clearly the Journal of Applied Psychology. The most dominant journal is the Leadership Quarterly with five publications. In terms of countries, the United States lead the list with twelve publications. The United Kingdom has five, Germany and Switzerland have one publication each. Professor D. Day contributes to four articles (2020, 2018, 2017, 2011), which is a considerable achievement given this highly selective sample. Moreover, G. Larson, C. Sandahl, and T. Soderhjelm contributed twice (2017, 2019). All other authors contributed once.

How true longitudinal LD studies have been conducted methodologically and what inconsistencies exist?

The research question is addressed following two recommended stages, a description of the characteristics and a thematic analysis (Levac et al., 2010). These two steps are assessed below.

Characteristics

Table 1 helps to address the research question of this study which is to evaluate how true longitudinal studies of LD are being investigated and what inconsistencies exist, primarily from a methodological perspective.

First, in terms of the nature of variables and strategy, the vast majority were quantitative (16), two studies utilized mixed methods, and only one used qualitative data (Andersson, 2010). This study’s criteria yielded a majority of experimental and survey strategies. However, archival data, narrative inquiry, observation, and action learning are represented as well.

Collectively, the studies form a sample of 2,776 participants. This number represents respondents that answered all longitudinal measures, thus drop-out participants, who have perhaps answered only the first measure and not the following ones, were not counted. In terms of sex, this combined sample is composed by 67% of males. The more recent studies seem to be more balanced in terms of gender though. In total, 88 waves of data were collected across all studies, resulting in an average of 4.2 waves per study. The maximum value observed is 13 waves of data (Middleton et al., 2019). The longest study lasted 20 years between first and last data collection (Howard, 1986) and the shortest study lasted 4 weeks (Quigley, 2013).

When it comes to the contextual settings, 6 publications researched one single company, 7 authors gathered participants from two or more companies, and 6 studies analyzed business students, mostly MBA students with work experience. The targeted companies, to cite only a few examples, were quite diverse, ranging from a large Australian corporation with more than 200,000 employees (Kragt & Day, 2020); to a museum leader development program with global participants (Middleton et al., 2019); to a multinational Indian-based IT company (Steele & Day, 2018); to middle managers of the headquarters of a regional grocery store chain in the United States. As for business students, the sample includes, among others, a top-ranked MBA program at a Spanish business school (Mayo et al., 2012); full-time MBA students at a large American university; and a graduate degree at a Dutch business school (Miscenko et al., 2017).

No form of intervention was found in 6 studies. The remaining 13 studies applied different LD trainings that varied in (1) length, ranging from 90 minutes to 145 hours; (2) content focus such as self-regulation, influence, feedback, team effectiveness; and (3) methods like lecture, role-play, discussion, readings, coaching.

By taking a look at the LD outcome measures, it is noticed that the two early studies of the sample, the ones that belong to the 1980s, were preoccupied with measuring some form of status, for instance career progress in terms of speed of promotion, and level of management achieved. After 2010, the focus of analysis changes from status to either cognitive outcomes (leader identity, self-perceived role knowledge) or behavioral outcomes (skills, competencies, efficacy). Established instruments and developed measures are both present.

Changing the conversation to the analytical approach of these works, it seems that it was not until 2011 that more appropriate procedures for longitudinal modelers started to emerge. This raises the question if more true longitudinal studies emerged because of more suitable tools available, or if these new tools were created given the importance to research human development in a longitudinal way.

Before 2011, the sample indicates the use of multiple regression equations, correlation analyses, ANOVAs, and ANCOVAs. After that year, an emergence and consolidation of more sophisticated methods is observed, like random coefficient modeling (RCM), latent growth model (LGM), multilevel modeling (MLM), hierarchical multivariate linear modeling (HMLM). In terms of the software tools used to execute these analyses, SPSS, R, HLM, NLME are highlighted.

Despite the present focus on methodologies, it was judged relevant to additionally chart the key findings of the studies included in this review. Table 2 maps this information chronologically by author.

Themes

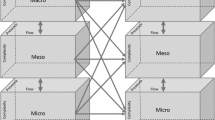

Themes were driven by the concepts, or the objects of analysis being used by scholars and derived by examining the “LD outcome measure” column of Table 1 as well as the full study. Specifically, a summarized thematic analysis was performed (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Variables were grouped together based on similarity. For instance, self-confidence and leadership efficacy are measuring behavioral change, hence a category called “behavioral” was created. Following this line of thinking, variables such as leader identity and self-perceived role knowledge are measuring cognitive change, thus the category “cognitive”. The same process was applied for the status category. After this procedure, the quantity of studies in each category was simply counted. Some studies are measuring more than one dimension, as shown below in Fig. 2.

As observed, most scholars are, not surprisingly, interested in researching behaviors, maybe because it is an inherent aspect of the organizational behavior field. The behavioral dimension is also the only one to intersect with the other two that emerged. Status outcomes were the primary variable for only two studies. And although no studies analyzed cognitive outcomes alone, researchers seem interested in understanding these factors as it greatly intersects with the behavior sphere. Lastly, only one true longitudinal study of LD measured all three categories (Kragt & Day, 2020). Table 3 provides more information based on these themes.

The themes reveal some interesting aspects. First, measuring status as a primary outcome is linked to older publications while the cognitive and behavioral dimensions are more recent concepts of interest. The status dimension is also associated with less waves of data but longer length of study in general. The opposite happens for studies focused on behavioral and cognitive aspects, they are characterized by collecting more waves of data in less time.

Even though the goal of this research is to analyze only business contexts, some diversity is observed in terms of specific setting (e.g., business schools, large companies, partnerships with consultancy firms), and location (e.g., USA, Europe, Australia, Japan, India). Except for India, no developing countries are observed, suggesting a potential research need.

In terms of strategies and interventions, conducting experiments is associated with the more recent studies. A lack is qualitative methods is also noticed. Additionally, the survey strategy is always present across the three themes. No standard regarding the type of intervention is detected, they are mostly trainings with slightly different areas of concentration.

The two studies focusing on status used more general analytic tools such as multiple regression and ANOVA analysis. More sophisticated tools are observed across the other two spheres and their intersections (e.g., LGM, RCM, HLM).

Discussion

The evidence indicates that the longitudinal LD area is young with the vast majority of studies being published after 2010. The combined sample sums 2,776 participants (67% male) and 88 waves of data. Most of these studies are quantitative, and mostly surveys or experiments. The context, as expected, is very much managerial and composed mostly by large companies and business schools in developed countries. Regarding LD outcomes, three major themes were found, status (e.g., level of leadership attained), behavioral (e.g., leadership effectiveness), and cognitive (e.g., leader identity).

Scoping reviews have the power to map a field of knowledge making gaps more evident (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). In this way, it is not difficult to notice that no developing countries are represented except from India, smaller companies are also not represented, and women are underrepresented as they compose one third of this review’s combined sample. Considering that leadership is highly contextual (Johns, 2006), it is understood that, if supported by insights originated from diverse contexts, the field could make significant progress in terms of bridging LD science and practice (Day et al., 2018).

Moreover, it is concerning to see almost no qualitative studies in this review. Despite the challenges associated with conducting longitudinal qualitative research in the social sciences (Thomson & Holland, 2003), this methodology has the potential to enrich the LD field with deeper insights. One promising path seems to be multiple perspective qualitative longitudinal interviews (MPQLI) (Vogl et al., 2018), a framework created to analyze related individuals (e.g., one’s peers, superiors, subordinates) and to deal with complex and voluminous data. Another hopeful avenue of research for LD is through the underdeveloped area of mixed methods longitudinal research (MMLR) (Vogl, 2023). The current study has been relying on the assumption that longitudinal designs are the most appropriate way to study LD (Day, 2011). Building on this and being more specific, MMLR may be even more appropriate to understand and explain LD given the complementary insights generated (Vogl, 2023). However, applying this type of methodology comes with a series of issues as well as high execution effort that need to be taken into consideration by future scholars (Plano Clark et al., 2015).

One additional issue associated with longitudinal research is deciding how many waves of data to collect and what is the ideal length of interval between measurement points (Ployhart & Vandenberg, 2010). In the present study, it is difficult to recognize any corresponding standard among the experimental studies. Some authors seem to be following the intervention’s length, for instance, Miscenko et al.‘s (2017) 7-week leadership program collected data at seven weekly time points, but the vast majority of studies do not offer explanations for the choices made. Even though most of these decisions are atheoretical and the ideal time interval is rarely known because it greatly depends on the phenomenon of interest, Wang et al. (2017) say this is a critical matter because it directly affects the change trajectory. Therefore, the science of longitudinal leadership research could benefit from more information about the decision rationale given the variables at hand. For example, for which kinds of leadership phenomena longer lengths are more valuable and vice versa? How many waves of data would be more suitable according to concept, levels of analysis, or research goals?

Regarding concepts, data shows that scholars are less interested in measuring status-related concepts (e.g., hierarchical level achieved), while behavioral variables are the most popular ones and cognitive variables can be considered emerging. Although each study naturally uses variables that are coherent with their research questions, the three dimensions presented earlier (Fig. 2) offer different and valuable perspectives to the development of leaders and leadership, so it is judged beneficial to cross dimensions whenever possible. For example, Kragt and Day (2020) is the only study that sheds light on status (e.g., promotion), behavior (e.g., managing stress), and cognitive aspects (e.g., leader identity).

As a summary, this paper contributes to theory in several ways. First, through mapping the methods being used to date; second, by identifying inconsistencies and gaps; third, by elaborating on ways in which the leadership field can advance; fourth, by understanding themes in terms of outcome variables; and lastly, through insights for management scholars and practitioners given the exclusive focus on business contexts.

Limitations

The present work is not immune to limitations, as no scientific work is. This study includes documents up to the year 2021, resulting in a three-year gap considering the submission date to this journal. Significant personal circumstances prevented the authors from pursuing publication earlier, so to mitigate this potential limitation, a modest cursory review is presented as described. Searching the Web of Science database from 2022 to 2024 using the seven search strings outlined in Appendix A, a list of 116 documents were gathered. Following the PRISMA-ScR framework (Tricco et al., 2018), records were screened (abstract and/or full text) based on the same pre-determined criteria described in the methodology section. Even though 12 records were closely assessed, only 2 peer-reviewed articles respected the parameters. They are identified below followed by a summarized discussion.

“How coaching interactions transform leader identity of young professionals over time” published in the International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring by Hughes and Vaccaro (2024) was the first record identified. This qualitative exploration utilizing semi-structured interviews before, during and after the coaching experience highlights through narrative inquiry analysis how coaching that is grounded in identity transformation practices are an important mechanism for emerging leaders as they navigate high degrees of professional and personal change in their lives. Despite the small sample size (six coaches), the three-phase data collection can be considered rare in qualitative studies of leadership development, representing a strength.

“Perceived changes in leadership behavior during formal leadership education” published in Public Personnel Management by Sørensen et al. (2023) was the second record identified. This multilevel three-year study with 62 leaders and 860 respondents found that leadership education has a considerable effect on leadership behaviors when it comes to tasks, relations, and change. Among the highlighted insights is the interesting fact that subordinates rated change in leadership behavior significantly lower compared to superiors and peers.

In addition to the limitations presented so far, scoping reviewers are encouraged to initially conduct the data charting process with at least two scholars working independently (Levac et al., 2010) and this was not possible to accomplish in the present study. Although agreeing with the above-mentioned recommendation, it is believed that the findings are not threatened by not executing this step, as the main motivation for it seems to be saving time when it comes to including studies. Thus, the only drawback for the current research was making the data charting process longer than it could have been.

The attempts to include gray literature were restricted to contacting LD subject-experts, which is a valid and effective strategy (Petticrew & Roberts, 2008), but there are additional tactics that could potentially lead to a larger sample. One example would be searching online databases for theses and dissertations around the theme. Future studies are encouraged to address that.

The experience of conducting a scoping review was perceived as “too manual”. Despite the confidence in the present results, it is difficult to ensure the inexistence of minor oversights as the process involved multiple Excel documents with dozens of tabs and thousands of lines each. Using a software was unfortunately not an option for the present study, but researchers interested in scoping reviews should consider using one.

The focus of the current review was purposefully restricted to business contexts. Although this is beneficial to the present goal and to obtain more specific insights, it leads to low generalizability power. Including studies from other LD contexts such as healthcare, military, and sports, can offer a good opportunity to learn across disciplines and potentially identify synergies for the benefit of leadership research as a whole.

Future research

Regarding the limitations highlighted above, it is encouraged that LD scholars conducting scoping reviews to focus on working within larger teams of colleagues as some scoping review procedures can be quite lengthy depending on the protocol chosen (e.g., a truly extensive search, data charting). Most of the limitations identified above could have been solved by that. And referring again to how data could not be obtained past 2021 for this study, it is encouraged that researchers engaged with scoping reviews include the most up to date records whenever possible.

Despite the search comprehensiveness demonstrated here, the present sample is relatively small. So, even though it is unknown if a larger sample is possible to achieve given this study’s scope, scholars are still encouraged to try to include more articles. Specifically, through searching more than five online databases, trying to expand the search for gray literature, and, if possible, performing searches in languages in addition to English.

Changing the conversation from the methodology of scoping reviews to the actual methodological contents of the sample, one gap that is easily noticed is the lack of qualitative or mixed-method studies, therefore these designs are encouraged for an enhanced perspective of LD in business contexts. Qualitative research has been growing strong in management science due to the value of their rich insights (Bluhm et al., 2011) and it seems that the LD field has plenty of space to leverage this opportunity. This is not to say that more quantitative designs are not needed, but right now it seems that the field can significantly grow from qualitative and mixed-methods contributions.

For sponsored authors or authors with a higher budget and a more numerous team, it would be interesting to conduct a scoping review similar to this one but not restricted to the business context as insights from other fields like health sciences, sports, education, military can help advance the science of LD. It would finally be interesting for a future scoping review of LD to organize the research through levels of analysis, namely intraindividual change, group change, and organizational change.

Even though the most recent studies analyzed by this scoping review worked with more gender balanced samples, male participants are predominant overall, hence future research is encouraged to continue working with a balanced proportion of males and females. Alternatively, all-female samples could leverage new insights as no studies under the current criteria have explored this angle yet. Relatedly, the LD field could unlock novel contributions by going beyond sex in terms of demographic characteristics. For example, age, race, social class, and gender identity are potentially good opportunities to extend knowledge.

Conclusion

The present scoping review intended to understand how true longitudinal studies of LD are being researched and what inconsistencies exist, primarily from a methodological perspective. After a rigorous search process ranging from 1900 to 2021, evidence was extracted from 19 peer-reviewed articles set in business contexts and measuring LD change with at least three waves of data. The current study elucidates gaps, patterns, and inconsistencies in terms of many aspects including nature of data, research strategy, participants, waves of data, concepts, analytical techniques, and key findings. Some observed highlights include the pattern to measure behavioral concepts and the emergent interest in measuring cognitive concepts. The procedures of the most recent works are shorter in length and more numerous in waves of data, the opposite was true a few decades ago. More sophisticated analytical techniques have been used in recent years as the field understands LD as a developmental science and art. However, there is an overreliance on quantitative methods leading to a bright future for qualitative and mixed-methods longitudinal researchers. Given the historical gender imbalance in participants studied (combined sample is 67% male), balanced or all-female samples can lead to original insights.

Appendix A

Search strings used in the five online databases.

Search 1 | longitudinal |

AND | |

“leader* development” OR “manage* development” OR “executive development” OR “supervisory development” OR “team development” OR “human resource$ development” | |

Search 2 | longitudinal |

AND | |

“leader* training” OR “manage* training” OR “executive training” OR “supervisory training” OR “team training” OR “human resource$ training” | |

Search 3 | longitudinal |

AND | |

“leader* program*” OR “manage* program*” OR “executive program*” OR “supervisory program*” OR “team program*” OR “human resource$ program*” | |

Search 4 | longitudinal |

AND | |

“leader* intervention” OR “manage* intervention” OR “executive intervention” OR “supervisory intervention” OR “team intervention” OR “human resource$ intervention” | |

Search 5 | longitudinal |

AND | |

“leader* education” OR “manage* education” OR “executive education” OR “supervisory education” OR “team education” OR “human resource$ education” | |

Search 6 | longitudinal |

AND | |

“leader* building” OR “manage* building” OR “executive building” OR “supervisory building” OR “team building” OR “human resource$ building” | |

Search 7 | longitudinal |

AND | |

coaching OR mentoring OR “360-degree feedback” OR “multi-source feedback” OR “multi-rater feedback” |

Appendix B

List of selected studies and basic details.

Author | Year | Title | Journal | Editor Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Howard, Ann | 1986 | College Experiences and Managerial Performance | Journal of Applied Psychology | United States |

Wakabayashi, Mitsuru; Graen, George; Graen, Michael; Graen, Martin | 1988 | Japanese Management Progress: Mobility Into Middle Management | Journal of Applied Psychology | United States |

Seifert, Charles F.; Yukl, Gary | 2010 | Effects of repeated multi-source feedback on the influence behavior and effectiveness of managers: A field experiment | Leadership Quarterly | United States |

Andersson, Thomas | 2010 | Struggles of managerial being and becoming: Experiences from managers’ personal development training | Journal of Management Development | United Kingdom |

Cherniss, Cary Grimm, Laurence G. Liautaud, Jim P. | 2010 | Process-designed training: A new approach for helping leaders develop emotional and social competence | Journal of Management Development | United Kingdom |

Abrell, Carolin; Rowold, Jens; Weibler, Jürgen; Moenninghoff, Martina | 2011 | Evaluation of a Long-Term Transformational Leadership Development Program | Zeitschrift für Personalforschung | Germany |

Day, DV; Sin, HP | 2011 | Longitudinal tests of an integrative model of leader development: Charting and understanding developmental trajectories | Leadership Quarterly | United States |

Mayo, M; Kakarika, M; Pastor, JC; Brutus, S | 2012 | Aligning or inflating your leadership self-image? A longitudinal study of responses to peer feedback in MBA teams | Academy of Management Learning & Education | United States |

Quigley, Narda R. | 2013 | A Longitudinal, Multilevel Study of Leadership Efficacy Development in MBA Teams | Academy of Management Learning & Education | United States |

Yeow, J; Martin, R | 2013 | The role of self-regulation in developing leaders: A longitudinal field experiment | Leadership Quarterly | United States |

Dragoni, Lisa Park, Haeseen Soltis, Jim Forte-Trammell, Sheila | 2014 | Show and tell: How supervisors facilitate leader development among transitioning leaders | Journal of Applied Psychology | United States |

Baron, Louis | 2016 | Authentic leadership and mindfulness development through action learning | Journal of Managerial Psychology | United Kingdom |

Miscenko, Darja; Guenter, Hannes; Day, David V. | 2017 | Am I a leader? Examining leader identity development over time | Leadership Quarterly | United States |

Larsson, G; Sandahl, C; Soderhjelm, T; Sjovold, E; Zander, A | 2017 | Leadership behavior changes following a theory-based leadership development intervention: A longitudinal study of subordinates’ and leaders’ evaluations | Scandinavian Journal of Psychology | United Kingdom |

Steele, Andrea R.; Day, David V. | 2018 | The Role of Self-Attention in Leader Development | Journal of Leadership Studies | United States |

Sandahl C., Larsson G., Lundin J., Söderhjelm T.M. | 2019 | The experiential understanding group-and-leader managerial course: long-term follow-up | Leadership and Organization Development Journal | United Kingdom |

Middleton, ED; Walker, DO; Reichard, RJ | 2019 | Developmental Trajectories of Leader Identity: Role of Learning Goal Orientation | Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies | United States |

Kragt, D; Day, DV | 2020 | Predicting Leadership Competency Development and Promotion Among High-Potential Executives: The Role of Leader Identity | Frontiers in Psychology | Switzerland |

D’Innocenzo, L; Kukenberger, M; Farro, AC; Griffith, JA | 2021 | Shared leadership performance relationship trajectories as a function of team interventions and members’ collective personalities | Leadership Quarterly | United States |

Data availability

The authors declare that the data is available upon request.

References

Andersson, T. (2010). Struggles of managerial being and becoming: Experiences from managers’ personal development training. Journal of Management Development,29(2), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011019305

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice,8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Arvey, R. D., Zhang, Z., Avolio, B. J., & Krueger, R. F. (2007). Developmental and genetic determinants of leadership role occupancy among women. Journal of Applied Psychology,92(3), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.693

Athanasopoulou, A., & Dopson, S. (2018). A systematic review of executive coaching outcomes: Is it the journey or the destination that matters the most? Leadership Quarterly,29(1), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.11.004

Atwater, L. E., & Waldman, D. (1998). 360 degree feedback and leadership development. Leadership Quarterly,9(4), 423–426.

Atwater, L. E., Dionne, S. D., Avolio, B. J., Camobreco, J. F., & Lau, A. W. (1999). A longitudinal study of the leadership development process: Individual differences predicting leader effectiveness. Human Relations,52(12), 1543–1562.

Ayoobzadeh, M., & Boies, K. (2020). From mentors to leaders: Leader development outcomes for mentors. Journal of Managerial Psychology,35(6), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-10-2019-0591

Bailey, C., & Fletcher, C. (2002). The impact of multiple source feedback on management development: Findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior,23(7), 853–867. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.167

Baltes, P. B. (1968). Longitudinal and cross-sectional sequences in the study of age and generation effects. Human Development,11, 145–171.

Bleidorn, W., Hill, P. L., Back, M. D., Denissen, J. J. A., Hennecke, M., Hopwood, C. J., Jokela, M., Kandler, C., Lucas, R. E., Luhmann, M., Orth, U., Wagner, J., Wrzus, C., Zimmermann, J., & Roberts, B. (2019). The policy relevance of personality traits. American Psychologist,74(9), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000503

Bluhm, D. J., Harman, W., Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (2011). Qualitative research in management: A decade of progress. Journal of Management Studies,48(8), 1866–1891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00972.x

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology,3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bray, D. W. (1964). The management progress study. American Psychologist,19(6), 419–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0038616

Chan, D. (1998). The conceptualization and analysis of change over time: An integrative approach incorporating longitudinal mean and covariance structures analysis (LMACS) and multiple indicator latent growth modeling (MLGM). Organizational Research Methods,1(4), 421–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814004

Cherniss, C., Grimm, L. G., & Liautaud, J. P. (2010). Process-designed training: A new approach for helping leaders develop emotional and social competence. Journal of Management Development,29(5), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011039196

Chilcott, J., Brennan, A., Booth, A., Karnon, J., & Tappenden, P. (2003). The role of modelling in prioritising and planning clinical trials. Health Technology Assessment,7(23). https://doi.org/10.3310/hta7230

Chun, J. U., Sosik, J. J., & Yun, N. Y. (2012). A longitudinal study of mentor and protégé outcomes in formal mentoring relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior,33, 1071–1094. https://doi.org/10.1002/job

Collins, D. B., & Holton, E. F. (2004). The effectiveness of managerial leadership development programs: A meta-analysis of studies from 1982 to 2001. Human Resource Development Quarterly,15(2), 217–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1099

Day, D. V. (2000). Leadership development: A review in context. Leadership Quarterly,11(4), 581–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.1981.10483720

Day, D. V. (2011). Integrative perspectives on longitudinal investigations of leader development: From childhood through adulthood. Leadership Quarterly,22(3), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.012

Day, D. V. (2024). Developing leaders and leadership: Principles, practices, and processes. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-59068-9

Day, D. V., & Dragoni, L. (2015). Leadership development: An outcome-oriented review based on time and levels of analyses. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior,2, 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111328

Day, D. V., & Sin, H. P. (2011). Longitudinal tests of an integrative model of leader development: Charting and understanding developmental trajectories. Leadership Quarterly,22(3), 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.011

Day, D. V., Harrison, M. M., & Halpin, S. M. (2009). An integrative approach to leader development: Connecting adult development, identity, and expertise. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203809525

Day, D. V., Fleenor, J. W., Atwater, L. E., Sturm, R. E., & McKee, R. A. (2014). Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. Leadership Quarterly,25(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.004

Day, D., Riggio, R., Conger, J., & Tan, S. (2018). Call for papers - special issue on 21st century leadership development: Bridging science and practice. Leadership Quarterly,29(6), I. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1048-9843(18)30810-5

Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Producing a systematic review. In D. A. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689).

Dragoni, L., Park, H., Soltis, J., & Forte-Trammell, S. (2014). Show and tell: How supervisors facilitate leader development among transitioning leaders. Journal of Applied Psychology,99(1), 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034452

Dvir, T., Eden, D., Avolio, B. J., & Shamir, B. (2002). Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: A field experiment. Academy of Management Journal,45(4), 735–744. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069307

Epitropaki, O., Kark, R., Mainemelis, C., & Lord, R. G. (2017). Leadership and followership identity processes: A multilevel review. Leadership Quarterly,28(1), 104–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.10.003

Gottfried, A. E., Gottfried, A. W., Reichard, R. J., Guerin, D. W., Oliver, P. H., & Riggio, R. E. (2011). Motivational roots of leadership: A longitudinal study from childhood through adulthood. Leadership Quarterly,22(3), 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.008

Guerin, D. W., Oliver, P. H., Gottfried, A. W., Gottfried, A. E., Reichard, R. J., & Riggio, R. E. (2011). Childhood and adolescent antecedents of social skills and leadership potential in adulthood: Temperamental approach/withdrawal and extraversion. Leadership Quarterly,22(3), 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.006

Harms, P. D., Spain, S. M., & Hannah, S. T. (2011). Leader development and the dark side of personality. Leadership Quarterly,22(3), 495–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.007

Howard, A. (1986). College experiences and managerial performance. Journal of Applied Psychology,71(3), 530–552. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.530

Howard, A., & Bray, D. W. (1988). Managerial lives in transition: Advancing age and changing times. Guilford Press.

Hughes, A., & Vaccaro, C. (2024). How coaching interactions transform leader identity of young professionals over time. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring,22(1), 130–148. https://doi.org/10.24384/3tw6-r891

Jacobs, R. L., & McClelland, D. C. (1994). Moving up the corporate ladder: A longitudinal study of the leadership motive pattern and managerial success in women and men. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research,46(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/1061-4087.46.1.32

Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review,31(2), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.20208687

Johnson, C. D., & Routon, P. W. (2024). Who feels taught to lead? Assessing collegiate leadership skill development. Journal of Leadership Education,23(1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/jole-01-2024-0013

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Ilies, R., & Gerhardt, M. W. (2002). Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology,87(4), 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765

Judge, T. A., Colbert, A. E., & Ilies, R. (2004). Intelligence and leadership: A quantitative review and test of theoretical propositions. Journal of Applied Psychology,89(3), 542–552. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.542

Kragt, D., & Day, D. V. (2020). Predicting leadership competency development and promotion among high-potential executives: The role of leader identity. Frontiers in Psychology,11(August), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01816

Lacerenza, C. N., Reyes, D. L., Marlow, S. L., Joseph, D. L., & Salas, E. (2017). Leadership training design, delivery, and implementation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology,102(12), 1686–1718. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000241.supp

Ladkin, D., & Taylor, S. S. (2010). Leadership as art: Variations on a theme. Leadership,6(3), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715010368765

Lester, P. B., Hannah, S. T., Harms, P. D., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Avolio, B. J. (2011). Mentoring impact on leader efficacy development: A field experiment. Academy of Management Learning and Education,10(3), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2010.0047

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science,5(69), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511814563.003

Li, W. D., Arvey, R. D., & Song, Z. (2011). The influence of general mental ability, self-esteem and family socioeconomic status on leadership role occupancy and leader advancement: The moderating role of gender. Leadership Quarterly,22(3), 520–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.009

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,62(10), e1–e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

Lord, R. G., & Hall, R. J. (2005). Identity, deep structure and the development of leadership skill. Leadership Quarterly,16(4), 591–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.06.003

Mayo, M., Kakarika, M., Pastor, J. C., & Brutus, S. (2012). Aligning or inflating your leadership self-image? A longitudinal study of responses to peer feedback in MBA teams. Academy of Management Learning and Education,11(4), 631–652. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2010.0069

McCall, M. W. (2004). Leadership development through experience. Academy of Management Executive,18(3), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.2004.14776183

McCall, M. W. (2010). Recasting leadership development. Industrial and Organizational Psychology,3(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2009.01189.x

Middleton, E. D., Walker, D. O., & Reichard, R. J. (2019). Developmental trajectories of leader identity: Role of learning goal orientation. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies,26(4), 495–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818781818

Mirvis, P. (2008). Executive development through consciousness-raising experiences. Academy of Management Learning and Education,7(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2008.32712616

Miscenko, D., Guenter, H., & Day, D. V. (2017). Am I a leader? Examining leader identity development over time. Leadership Quarterly,28(5), 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.01.004

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Alttman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine,151(4), 264–269.

Moher, D., Stewart, L., & Shekelle, P. (2015). All in the family: Systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Systematic Reviews,4(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0163-7

Muir, D. (2014). Mentoring and leader identity development: A case study. Human Resource Development Quarterly,25(3), 349–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology,18(143), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315159416

Murphy, S. E., & Johnson, S. K. (2011). The benefits of a long-lens approach to leader development: Understanding the seeds of leadership. Leadership Quarterly,22(3), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.004

Oliver, P. H., Gottfried, A. W., Guerin, D. W., Gottfried, A. E., Reichard, R. J., & Riggio, R. E. (2011). Adolescent family environmental antecedents to transformational leadership potential: A longitudinal mediational analysis. Leadership Quarterly,22(3), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.010

Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis,18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2008). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887

Plano Clark, V. L., Anderson, N., Wertz, J. A., Zhou, Y., Schumacher, K., & Miaskowski, C. (2015). Conceptualizing longitudinal mixed methods designs: A methodological review of health sciences research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research,9(4), 297–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814543563

Ployhart, R. E., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2010). Longitudinal research: The theory, design, and analysis of change. Journal of Management,36(1), 94–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352110

Quigley, N. R. (2013). A longitudinal, multilevel study of leadership efficacy development in MBA teams. Academy of Management Learning & Education,12(4), 579–602. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2011.0524

Rajulton, F. (2001). The fundamentals of longitudinal research: An overview. Canadian Studies in Population,28(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.25336/p6w897

Rogosa, D. R., & Willett, J. B. (1983). Demonstrating the reliability of the difference score in the measurement of change. Journal of Educational Measurement,20(4), 335–343.

Rogosa, D., Brandt, D., & Zimowski, M. (1982). A growth curve approach to the measurement of change. Psychological Bulletin,92(3), 726–748. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.92.3.726

Seifert, C. F., & Yukl, G. (2010). Effects of repeated multi-source feedback on the influence behavior and effectiveness of managers: A field experiment. Leadership Quarterly,21(5), 856–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.07.012

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. In Etica e Politica. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof

Sørensen, P., Hansen, M. B., & Villadsen, A. R. (2023). Perceived changes in leadership behavior during formal leadership education. Public Personnel Management,52(2), 170–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/00910260221136085

Springborg, C. (2010). Leadership as art - leaders coming to their senses. Leadership,6(3), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715010368766

Steele, A. R., & Day, D. V. (2018). The role of self-attention in leader development. Journal of Leadership Studies,12(2), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.21570

Taris, T. W. (2000). A primer in longitudinal data analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Thomson, R., & Holland, J. (2003). Hindsight, foresight and insight: The challenges of longitudinal qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice,6(3), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000091833