Abstract

Social media has become prominent in recent years, especially among the young population, and they also substantially impact young people’s eating habits. Furthermore, social media posts and visual interactions may trigger hedonic hunger, an increased desire for highly palatable food. This study aimed to explore the relationship between social media use and the concept of hedonic hunger in a sample of college students. 860 participants between 18 and 39 were recruited for the study. Data including demographic variables, weight, height, the Scale of Effects of Social Media on Eating Behavior (SESMEB), and the Turkish version of the Power of Food Scale (PFS) were gathered based on students’ self-reports via face-to-face interviews. The most used social media outlet among all students was Instagram (60.1%), the average time spent on social media was 3.56 ± 1.91 h, and females spent significantly more time on social media than males (p < 0.001). The mean PFS score was 3.52 ± 0.77, and the subscale scores for food availability, food present, and food tasted were 3.26 ± 0.99, 3.49 ± 0.89, and 3.76 ± 0.87, respectively. Female students who spent more than 2 h on social media had higher scores on SESMEB than those who spent 2 h or less a day (p = 0.015). A significantly positive correlation was found between SESMEB scores and PFS aggregated scores (r = 0.381) and subscale scores (for food availability, present, and tasted, r = 0.369; r = 0.354; and r = 0.282, respectively). Each 1-unit increase in the SESMEB score leads to an 8% increase in the risk of hedonic hunger. Considering the impact of social media on young people’s eating habits and developing strategies may be crucial in shaping their eating patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Being a university student is a prominent milestone in the transition from childhood to adulthood and a critical period in which forward-looking dietary habits are shaped. Several factors, including distance from family, greater independence in food preferences, limited food budget, and interactions with new social groups and food cultures, contribute to the changing eating habits of young adults (Sprake et al., 2018; Yolcuoğlu & Kızıltan, 2022). Particularly over the last few years, in addition to all these drivers for this population, the effect of social media use has been undeniable. Social media (often called social networking sites) is an umbrella term for digital technologies that allow people to connect, interact, produce, and share content (Dumford et al., 2023). According to the 2023 Global Digital Report, 4.95 billion people, or 61.4% of the world’s population, use social media, with an average duration of 2 h 24 min. Supportively, social media usage is also widely spread in Türkiye, with 62.55 million social media users in January 2023, representing 73.1% of the total population (Kemp, 2023). Although the social media usage time among college students varies by country (Kim et al., 2011; Parlak Sert & Başkale, 2023), most young people typically spend a great deal of time on outlets such as Instagram, YouTube, Twitter (X), TikTok, and Twitch, which highlight visual and audio stimuli (Guan & Duan, 2020; Mardhatilah et al., 2023). Motivations for young people using social media include entertainment, research, making friends, sharing and learning experiences, pursuing academic opportunities, and building national and international academic networks (Hussain, 2012; Saha & Guha, 2019).

Moreover, in recent years, food, nutrition, and health-themed topics on social media have garnered interest among young people (Klassen et al., 2018). In particular, food advertisements on social media, food or nutrition-related posts by influencers, eating video content, including mukbang videos that depict broadcasters gorging on vast portions of food, and exposure to a variety of food-related content can be proposed as crucial contributors to shaping the food preferences and eating habits of young people (Anjani et al., 2020; Denniss et al., 2023). In addition, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have documented a positive relationship between the duration of social media exposure, the frequency of social media use, browsing photos on social networking sites, and food cravings, eating disorders, and body image concerns (Blanchard et al., 2023; Filippone et al., 2022; Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). A recent study by Sina et al. revealed that social media exposure is associated with an elevated consumption frequency of unhealthy snacks, fast food, sugar-sweetened beverages, and daily caffeine and sugar intake (Sina et al., 2022). One of the plausible mechanisms of this phenomenon may be interpreted as exposure to visual cues of food (videos, pictures, etc.) stimulating attention and neural activation in brain areas related to visual processing and reward in humans, thus increasing the eating behavior potential (Simmons et al., 2005). These stimuli, which are important cues to food intake, can be linked to the concept of hedonic hunger, which is defined as the pleasure-based desire to eat highly palatable foods (e.g., high in salt, fat, and sugar) even if people do not have physiological hunger (Crane et al., 2023; Lowe & Butryn, 2007). The concept of hedonic hunger is based on three distinct neurobiological components of “incentive salience theory”: “liking,” “wanting,” and “learning.” While “liking” is the hedonic element that reflects direct experience or expectation of pleasure, wanting is the reward-seeking (or incentive motivation) element that drives increased appetite, food cravings, and other behaviors related to increased motivation to food intake (Berridge & Robinson, 1998; Egecioglu et al., 2011). All these hedonic motivations are regulated by the brain’s m-opioid system, and the brain develops subjective pleasurable sensations that can even induce an individual to eat compulsively. In this context, the hedonic pathways can suppress the homeostatic mechanism and increase the urge to consume highly palatable foods with high energy density, even when the individual already has significant energy reserves and hunger and appetite sensations are low (Hernández Ruiz de Eguilaz et al., 2018). Food advertisements and exposure to written and visual content during the time spent on various social media outlets could act as cues that shape ingestive behaviors, notably toward ingesting highly processed and hyper-palatable foods, thus potentially triggering hedonic behaviors (Arrona-Cardoza et al., 2023).

The relationship between social media use and eating behavior among college students has already been documented in the literature from diverse perspectives (Aljefree & Alhothali, 2022; Huang et al., 2023; Law & Jevons, 2023); however, according to the author’s knowledge, its association with the concept of hedonic hunger has not been elucidated. Thus, this study aims to reveal the role of social media use on eating behavior and its association with hedonic hunger.

Methods

Data collection and participants

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted with undergraduate students enrolled in the 2022–2023 academic calendar at a foundation university in Istanbul, Türkiye. The minimum sample size was calculated to be 375 with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence interval; consequently, the study’s sample size consisted of 860 students. The college students who fulfilled the eligibility criteria of being over 18 years of age and volunteering to participate in the study were recruited through the convenience sampling method. Data were gathered based on the students’ self-reports via face-to-face interviews. This study was performed in accordance with the guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures were approved by the Marmara University Faculty of Health Science Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee with date and number 24.11.2022/106. Written informed consent was provided by all participants in the study.

Measures

Data Collection Form

The data collection form consists of several parts, including demographic features, anthropometric characteristics (self-reported weight and height), faculty/department and grade, living arrangement, smoking status, alcohol consumption and frequency, questions about examining social media use, Scale of Effects of Social Media on Eating Behavior (SESMEB), and Power of Food Scale (PFS). The body mass index (BMI) was obtained from self-reported weight and height data using the metric formula: weight kg/height m2 and categorized according to World Health Organization criteria as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.99 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.99 kg/m2), or obese (≥ 30.0 kg/m2) (World Health Organization, 2022).

The Scale of Effects of Social Media on Eating Behavior Scale (SESMEB)

The SESMEB was developed by Keser et al. in 2020 (alpha 0.928) to evaluate the students’ eating behaviors according to their use of social media (Keser et al., 2020). This five-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from 0 = never to 5 = always, comprises a sub-scale and 18 questions and does not contain adverse phrases. The overall score was computed by summing each item, and the possible scores ranged from 18 to 90. As the score increases, it indicates that the effect of social media on eating behavior is becoming more pronounced.

Turkish version of the power of Food Scale (PFS-Tr)

The Power of Food Scale (PFS) was developed by Lowe et al. in 2009 (Lowe et al., 2009) and was validated in Turkish by Ulker et al. in 2020 to measure the hedonic hunger motives to consume hyper-palatable foods (Ulker et al., 2021). The scale follows a 5-point Likert-type answer, ranging from ‘don’t agree at all’ to ‘strongly agree.’ Although the original form consisted of 15 items, it was reduced to 13 after the Turkish validation. Turkish version of PFS (PFS-Tr) comprises three subscales. The first is the “food available” subscale (alpha 0.849), which measures general thoughts about foods (items 1, 2, 9, and 10). Second, the “food present” subscale (alpha 0.797) assesses attraction to food directly available to the individual (items 3, 4, 5, and 6). Finally, the “food tasted” subscale (alpha 0.82) evaluates the desire for/pleasure derived from food when first tasted (items 7, 8, 11, 12, and 13). Each item has been rated from 1 to 5, and the PFS aggregated, and subscale scores are generated by summing the item scores and dividing the total by the number of items. Furthermore, PFS measures consumption motivation and strives to understand how the palatability of foods drives thoughts, feelings, and behaviors rather than directly assessing dietary intake (Crane et al., 2023).

Statistics

Sample characteristics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as percentages (%) and numbers (n) for qualitative variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (Windows version 23). Since the data were presented in two groups, male and female students, the Chi-square test was used for qualitative variables, and the Student t test or its non-parametric equivalent, the Mann-Whitney U test, was used for univariate analysis of continuous results. Variables that were found to correlate with the SESMEB score were analyzed with a linear regression. Two different binary logistic regressions were performed to examine the effects of gender and the SESMEB score on the likelihood of having hedonic hunger. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test and the Omnibus test of the model coefficients were performed to determine the goodness of fit. The confidence interval was determined as 95% in all analyses, and the results were considered statistically significant for p < 0.05.

Results

General characteristics of the participants

This study was designed to highlight the role of social media use on eating behavior and how it pertains to hedonic hunger. The total sample included 860 college students, and descriptive characteristics of respondents by gender are depicted in Table 1. Most participants were female (65.2%, n = 561), with a mean age of 21.4 ± 2.4 years. The majority of the students enrolled in the study were students from the Faculty of Engineering (20.9%), the Faculty of Health Sciences (19.5%), and the Faculty of Art and Sciences (9.9%). Approximately 50% of the students lived with their families. The majority of participants (63.6%, n = 547) were non-smokers, and most reported drinking alcohol (77.1%, n = 663). In terms of gender, more than half of both male and female students had a high prevalence of being non-smokers (69.7%; 52.2%) (p < 0.001) and using alcohol (75.6%; 79.9%).

The mean BMI of all participants was 22.3 ± 3.7 kg/m2, and overweight and obesity were detected in 20.9% of the students. The mean BMI of males was slightly (2.68 kg/m2) but significantly higher than that of female students (p < 0.001). The prevalence of overweight and obesity is higher in males than in females (p < 0.001), with 9.9% of females overweight and 2.9% having obesity, whereas 31.1% of males were overweight and 5.0% had obesity. The overall sample had comparable and high rates of those who wanted to lose weight (44.8%) and those who were satisfied with their current weight (43.8%). While most female students (51.5%, n = 289) wanted to lose weight, most of those who wanted to gain weight were male (57.1%, n = 56) (p < 0.001).

Social media usage and SESMEB

The most widely used social media outlet among all students was Instagram (60.1%), and this trend was similar for both females (64.8%) and males (51%). It was also pointed out that 75% of female students and 63.9% of male students spent more than 2 h daily on social media, known as heavy users (p < 0.001) (Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2020). The average time spent on social media was 3.56 ± 1.91 h, and females spent significantly more time on social media than males (p < 0.001). As presented in Table 1, the SESMEB score used for measuring the effects of social media on eating behavior among overall students was 37.26 ± 11.34, with significantly higher in females (38.30 ± 10.86) (p < 0.001). Additionally, in comparison to male students, over half of the female students responded that the usage of social media affects their eating behavior (60.2%), that the visuals on social media affect their food choices (78.1%), and that they follow the recipes seen on social media (85.6%) (p < 0.001).

The relationship between the students’ daily social media usage time and the SESMEB score was demonstrated in Table 2. It was determined that female students who spent more than 2 h a day on social media had higher scores on SESMEB than those who spent 2 h or less a day (p = 0.015). No correlation was reported between the SESMEB score and the BMI of the students. A significant positive association was noted between average time spent on social media and SESMEB scores; however, this relationship was weak (r = 0.115; p < 0.001).

Hedonic hunger

The mean PFS (3.52 ± 0.77) and subscale scores, including food availability (3.26 ± 0.99), food present (3.49 ± 0.89), and food tasted (3.76 ± 0.87), used to interpret hedonic hunger, were over 2.5 in all students, suggesting that they were predisposed to hedonic hunger toward foods. In addition, it was revealed that female students’ mean PFS aggregated and subscale scores were significantly higher compared to males, and the highest score was observed for the subfactor of “food tasted” (p < 0.001). Corroborating these findings, the results of the binary logistic regression (data not shown) revealed that gender affected students’ hedonic hunger status. The odds of hedonic hunger were 2.76 times greater for the female students in comparison to the male students (Wald chi-square 19.780, df = 1, OR = 2.76, [95% CI: 1.77–4.33], p < 0.001). As illustrated in Table 2, the scores of the PFS aggregated and the subscales except “food tasted” were significantly higher for the female students who spent more than 2 h per day on social media than those who spent 2 h or less per day.

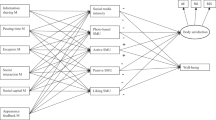

Table 3 presents the correlations of SESMEB with respondents’ BMI, hedonic hunger-related scores, and social media duration. Accordingly, a significantly positive but moderate correlation was found between SESMEB scores and PFS aggregated scores (r = 0.381; p < 0.001) and subscale scores (for food availability, food present, and food tasted, r = 0.369; p < 0.001, r = 0.354; p < 0.001, and r = 0.282; p < 0.001, respectively). Supportingly, according to the binary logistic regression model, each 1-unit increase in the SESMEB score leads to an 8% increase in the risk of hedonic hunger (Wald chi-square 36,146, df = 1, OR = 1.087, [95% CI: 1.06–1.12], p < 0.001) (data not shown). Furthermore, the “food availability” subscale of the students significantly and weakly correlated with BMI (r = 0.133; p < 0.001). A significant, although weak, association was established between the average time spent on social media and all subscales of hedonic hunger. Using a linear regression model, we also investigated the association between PFS and SESMEB scores (Table 4). For the total group, high PFS aggregated score [β (95%CI) = 0.026 (0.022–0.030), p < 0.001], “food available” [β (95%CI) = 0.032 (0.027–0.037), p < 0.001), “food present” [β (95%CI) = 0.032 (0.023–0.033), p < 0.001] and “food tasted” [β (95%CI) = 0.022 (0.017–0.027), p < 0.001] scores were independently associated with high SESMEB, and explained 13.6% of food available, 12.5% of food present and 7.9% of food tasted.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study conducted with a substantial sample of college students to explore the relationship between social media use and the concept of hedonic hunger. The extensive use of social media among college students highlights that the power of social media on young adults should not be overlooked and that this network can influence young people’s eating behaviors (Blanchard et al., 2023; Qutteina et al., 2019), as it has in all aspects of their lives. Supportingly, the present study concluded that social media affects students’ eating behaviors based on questions regarding social media use and SESMEB scores. The majority of students stated that social media impacted their eating behavior, which was significantly higher among female students compared to males. Similar patterns have been observed in other studies using this scale (Eşer Durmaz et al., 2023; Muthia et al., 2022). One of the main theories underlying why social media affects females’ eating behaviors can be attributed to the sociocultural model. According to this theory, females’ greater internalization of unrealistic body image content they are exposed to on social media might influence their eating behaviors (Qutteina et al., 2019; Thompson et al., 1999).

In our study, the PFS score was employed to analyze the findings of the students in the framework of hedonic hunger. Compared to studies with similar populations involving PFS, our study’s mean aggregate PFS score was higher (Abdulla et al., 2023; Saçti et al., 2022; Taş & Gezer, 2022). This difference might be attributable to the study being conducted in one of the country’s metropolitan cities, and students had easy access to chain and fast-food restaurants. Also, the PFS score and subscales were determined to be significantly higher in female students than in males, parallel to several studies (Açik et al., 2021; Aliasghari et al., 2020). Despite the majority of studies in the literature indicating that females are more susceptible to reward-related dietary intake (Legget et al., 2018), there are also varying outcomes (Martens et al., 2013). When molecular mechanisms of hedonic hunger are investigated, estrogen has been shown to strongly implicate food motivation and reward mechanisms and target the prefrontal cortex, a region involved in hedonic reward (Novelle & Diéguez, 2019).

The concept of hedonic hunger as a tendency toward more palatable, energy-dense foods beyond homeostatic hunger raises the question of whether there might be a positive relationship between hedonic hunger and BMI (Bilici et al., 2020; Chmurzynska et al., 2021). However, conflicting results have been shown in the literature; the majority of studies do not document a significant correlation between BMI and PFS outcomes (Lowe et al., 2009; Yoshikawa et al., 2012). Supportively, the current study demonstrated no significant association between BMI and PFS aggregated score and subscales other than “food available.” Similarly, the study conducted by Aliasghari et al. showed that there was a relationship between the “food available” subscales and BMI (Aliasghari et al., 2020).

Social media content is poorly controlled, and food and beverage establishments have been known to exploit the social vulnerability of young adults through the use of image-based marketing tactics, including peer ambassadors and celebrity endorsements (Freeman et al., 2016). People are constantly exposed to food-related content on social media, and the growing interest in this type of content on social media has resulted in the popular mass media calling this phenomenon ‘FoodPorn’ (Ventura et al., 2021). We revealed a positive correlation between the SESMEB, PFS aggregated, and subscale scores. Although no study explored the effects of hedonic hunger and social media, neuroscience research suggests that visual exposure to food may affect appetite-related brain activity (Schienle et al., 2009; Spence et al., 2016). Moreover, parallel to our findings, a mixed-method systematic review by Rounsefell et al. concluded that exposure to food-related posts on social media increased feelings of hunger, regardless of satiety level (Rounsefell et al., 2020). Also, a recent study conducted by Zeeni et al. demonstrated that exposure to junk food-related content on social media negatively affects appetite and food choices (Zeeni et al., 2024). According to the latest systematic review by Wu et al., exposure to certain food content on social media can lead to an increased intake of the foods that are viewed (Wu et al., 2024).

Limitations

Despite the advantage of reaching a large sample size compared to similar studies in the literature, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the BMI of the students was calculated by self-reported measures, which may result in under or overestimation. Furthermore, no data was collected regarding students’ exercise and physical activity status. Considering that physical activity level can affect many parameters, it is recommended that this issue be investigated in more detail in future studies. Additionally, students’ use of social outlets was reported based on the smartphones they carry with them; social media usage on other electronic devices is not included. This research represents the information and thoughts of the interviewed participants within the timeframe they responded and does not have the opportunity to determine the changes that may occur over time. It is suggested that further longitudinal research should be conducted to determine the actual change in behaviors due to social media occupation.

Conclusion

In line with the findings obtained from the study, social media may be a crucial factor in both eating behavior and the formation of hedonic hunger. This situation may have negative consequences on people’s physiological and mental health, and it is very important to determine the reasons that push people to this behavioral pattern and take precautions against them. While addressing eating behaviors in clinical practice, exploring factors such as how much exposure to social media and what content is more scrutinized will also be effective in guiding young people appropriately. For this reason, raising awareness about being a conscious social media user is needed in order to avoid being at risk of obesity and sustain healthy eating practices. Therefore, young people should be encouraged to learn how to use these platforms efficiently under the supervision of their families before university.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- PFS:

-

Power of Food Scale

- PFS-Tr:

-

Turkish version of the Power of Food Scale

- SESMEB:

-

The Scale of Effects of Social Media on Eating Behavior

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

References

Abdulla, N. K., Obaid, R. R., Qureshi, M. N., Asraiti, A. A., Janahi, M. A., Abu Qiyas, S. J., Faris, M. A., & I., E. (2023). Relationship between hedonic hunger and subjectively assessed sleep quality and perceived stress among university students: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon,9(4), e14987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14987

Açik, M., Bozdağ, A. N. S., & Çakiroğlu, F. P. (2021). The quality and duration of sleep are related to hedonic hunger: A cross-sectional study in university students. Sleep and Biological Rhythms,19(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-020-00303-8

Aliasghari, F., Asghari Jafarabadi, M., Lotfi Yaghin, N., & Mahdavi, R. (2020). Psychometric properties of Power of Food Scale in Iranian adult population: Gender-related differences in hedonic hunger. Eating and Weight Disorders,25(1), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0549-3

Aljefree, N. M., & Alhothali, G. T. (2022). Exposure to food marketing via social media and obesity among university students in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105851

Anjani, L., Mok, T., Tang, A., Oehlberg, L., & Goh, W. B. (2020). Why do people watch others eat food? An empirical study on the motivations and practices of Mukbang viewers. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376567

Arrona-Cardoza, P., Labonté, K., Cisneros-Franco, J. M., & Nielsen, D. E. (2023). The effects of Food Advertisements on Food Intake and neural activity: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of recent experimental studies. Advances in Nutrition,14(2), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advnut.2022.12.003

Berridge, K. C., & Robinson, T. E. (1998). What is the role of dopamine in reward: Hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Research Reviews,28, 309–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0173(98)00019-8

Bilici, S., Ayhan, B., Karabudak, E., & Koksal, E. (2020). Factors affecting emotional eating and eating palatable food in adults. Nutrition Research and Practice,14(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2020.14.1.70

Blanchard, L., Conway-Moore, K., Aguiar, A., Önal, F., Rutter, H., Helleve, A., Nwosu, E., Falcone, J., Savona, N., Boyland, E., & Knai, C. (2023). Associations between social media, adolescent mental health, and diet: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews,24(S2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13631

Chmurzynska, A., Mlodzik-Czyzewska, M. A., Radziejewska, A., & Wiebe, D. J. (2021). Hedonic hunger is Associated with intake of certain high-fat food types and BMI in 20- to 40-Year-old adults. Journal of Nutrition,151(4), 820–825. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxaa434

Crane, N. T., Butryn, M. L., Gorin, A. A., Lowe, M. R., & LaFata, E. M. (2023). Overlapping and distinct relationships between hedonic hunger, uncontrolled eating, food craving, and the obesogenic home food environment during and after a 12-month behavioral weight loss program. Appetite,185(February). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.106543

Denniss, E., Lindberg, R., & McNaughton, S. A. (2023). Quality and accuracy of online nutrition-related information: A systematic review of content analysis studies. Public Health Nutrition,26(7), 1345–1357. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980023000873

Dumford, A. D., Miller, A. L., Lee, C. H. K., & Caskie, A. (2023). Social media usage in relation to their peers: Comparing male and female college students’ perceptions. Computers and Education Open,4(December 2022), 100121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2022.100121

Egecioglu, E., Skibicka, K. P., Hansson, C., Alvarez-Crespo, M., Friberg, A., Jerlhag, P., Engel, E., J. A., & Dickson, S. L. (2011). Hedonic and incentive signals for body weight control. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders,12(3), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-011-9166-4

Eşer Durmaz, S., Keser, A., & Tunçer, E. (2023). Effect of emotional eating and social media on nutritional behavior and obesity in university students who were receiving distance education due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health (Germany),31(10), 1645–1654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01735-x

Filippone, L., Shankland, R., & Hallez, Q. (2022). The relationships between social media exposure, food craving, cognitive impulsivity and cognitive restraint. Journal of Eating Disorders,10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00698-4

Freeman, B., Kelly, B., Vandevijvere, S., & Baur, L. (2016). Young adults: Beloved by food and drink marketers and forgotten by public health? Health Promotion International,31(4), 954–961. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav081

Guan, Y., & Duan, W. (2020). The mediating role of visual stimuli from media use at bedtime on psychological distress and fatigue in college students: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Mental Health,7(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2196/11609

Hernández Ruiz de Eguilaz, M., Martínez de Morentin Aldabe, B., Almiron-Roig, E., Pérez-Diez, S., San Cristóbal Blanco, R., Navas-Carretero, S., & Martínez, J. A. (2018). Multisensory influence on eating behavior: Hedonic consumption. Endocrinologia Diabetes Y Nutricion,65(2), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endinu.2017.09.008

Holland, G., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). Review article a systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image,17, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008

Huang, P. C., Latner, J. D., O’Brien, K. S., Chang, Y. L., Hung, C. H., Chen, J. S., Lee, K. H., & Lin, C. Y. (2023). Associations between social media addiction, psychological distress, and food addiction among Taiwanese university students. Journal of Eating Disorders,11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00769-0

Hussain, I. (2012). A Study to Evaluate the Social Media Trends among University Students. 64, 639–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.075

Kemp, S. (2023). Global Social Media Statistics. Datareportal, Global Social Media Statistics. https://datareportal.com/social-media-users

Keser, A., Baylndlr-Gümüş, A., Kutlu, H., & Öztürk, E. (2020). Development of the scale of effects of social media on eating behaviour: A study of validity and reliability. Public Health Nutrition,23(10), 1677–1683. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019004270

Kim, Y., Sohn, D., & Choi, S. M. (2011). Cultural difference in motivations for using social network sites: A comparative study of American and Korean college students. Computers in Human Behavior,27(1), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.08.015

Klassen, K. M., Douglass, C. H., Brennan, L., Truby, H., & Lim, M. S. C. (2018). Social media use for nutrition outcomes in young adults: A mixed-methods systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity,15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0696-y

Law, R., & Jevons, E. F. P. (2023). Exploring the perceived influence of social media use on disordered eating in nutrition and dietetics students. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics,36(5), 2050–2059. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.13212

Legget, K. T., Cornier, M. A., Bessesen, D. H., Mohl, B., Thomas, E. A., & Tregellas, J. R. (2018). Greater reward-related neuronal response to Hedonic Foods in Women compared with men. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.),26(2), 362–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22082

Lowe, M. R., & Butryn, M. L. (2007). Hedonic hunger: A new dimension of appetite? Physiology and Behavior,91(4), 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.006

Lowe, M. R., Butryn, M. L., Didie, E. R., Annunziato, R. A., Thomas, J. G., Crerand, C. E., Ochner, C. N., Coletta, M. C., Bellace, D., Wallaert, M., & Halford, J. (2009). The Power of Food Scale. A new measure of the psychological influence of the food environment. Appetite,53(1), 114–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.016

Mardhatilah, D., Omar, A., Thurasamy, R., & Juniarti, R. P (2023). Digital Consumer Engagement: Examining the impact of Audio and visual Stimuli exposure in Social Media. Information Management and Business Review,15(4), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.22610/imbr.v15i4(SI)I.3580

Martens, M. J. I., Born, J. M., Lemmens, S. G. T., Karhunen, L., Heinecke, A., Goebel, R., Adam, T. C., & Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S. (2013). Increased sensitivity to food cues in the fasted state and decreased inhibitory control in the satiated state in the overweight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition,97(3), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.044024

Muthia, A. S., Margawati, A., Fitranti, D. Y., Dieny, F. F., & Hananingtyas, A. (2022). Correlation between eating Behavior and Use of Social Media with Energy-dense food intake based on gender among students in Semarang, Indonesia. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences,10(E), 602–610. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2022.9289

Novelle, M. G., & Diéguez, C. (2019). Updating gender differences in the control of homeostatic and hedonic food intake: Implications for binge eating disorder. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology,497(March), 110508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2019.110508

Parlak Sert, H., & Başkale, H. (2023). Students’ increased time spent on social media, and their level of coronavirus anxiety during the pandemic, predict increased social media addiction. Health Information and Libraries Journal,40(3), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12448

Qutteina, Y., Nasrallah, C., Kimmel, L., & Khaled, S. M. (2019). Relationship between social media use and disordered eating behavior among female university students in Qatar. Journal of Health and Social Sciences,4(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.19204/2019/rltn7

Rounsefell, K., Gibson, S., McLean, S., Blair, M., Molenaar, A., Brennan, L., Truby, H., & McCaffrey, T. A. (2020). Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: A mixed methods systematic review. Nutrition and Dietetics,77(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12581

Saçti, T., Koç, G., Gödek, Ş., Gözün, M., & İlyasoğlu, H. (2022). Hedonic Hunger Level of Health Science Students: Cross-sectional research. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Health Sciences,7(2), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.5336/healthsci.2021-84387

Saha, S. R., & Guha, A. K. (2019). Impact of Social Media Use of University students. International Journal of Statistics and Applications,9(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.statistics.20190901.05

Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Goldfield, G. S., Kingsbury, M., Clayborne, Z., & Colman, I. (2020). Social media use and parent–child relationship: A cross-sectional study of adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology,48(3), 793–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22293

Schienle, A., Schäfer, A., Hermann, A., & Vaitl, D. (2009). Binge-eating disorder: Reward sensitivity and brain activation to images of Food. Biological Psychiatry,65(8), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.028

Simmons, W. K., Martin, A., & Barsalou, L. W. (2005). Pictures of appetizing foods activate gustatory cortices for taste and reward. Cerebral Cortex,15(10), 1602–1608. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhi038

Sina, E., Boakye, D., Christianson, L., Ahrens, W., & Hebestreit, A. (2022). Social Media and children’ s and adolescents’ diets: A systematic review of the underlying Social and physiological mechanisms. Advances in Nutrition,13(3), 913–937. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmac018

Spence, C., Okajima, K., David, A., Petit, O., & Michel, C. (2016). Brain and cognition eating with our eyes: From visual hunger to digital satiation. Brain and Cognition,110, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2015.08.006

Sprake, E. F., Russell, J. M., Cecil, J. E., Cooper, R. J., Grabowski, P., Pourshahidi, L. K., & Barker, M. E. (2018). Dietary patterns of university students in the UK: A cross-sectional study. Nutrition Journal,17(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-018-0398-y

Taş, F., & Gezer, C. (2022). The relationship of hedonic hunger with food addiction and obesity in university students. Eating and Weight Disorders,27(7), 2835–2843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01436-0

Thompson, J. K., Coovert, M. D., & Stormer, S. M. (1999). Body image, social comparison, and eating disturbance: A covariance structure modeling investigation. International Journal of Eating Disorders,26(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199907)26:1%3C43::AID-EAT6%3E3.0.CO;2-R

Ulker, I., Ayyildiz, F., & Yildiran, H. (2021). Validation of the Turkish version of the power of food scale in adult population. Eating and Weight Disorders,26(4), 1179–1186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01019-x

Ventura, V., Cavaliere, A., & Iannò, B. (2021). #Socialfood: Virtuous or vicious? A systematic review. Trends in Food Science and Technology,110(February), 674–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.018

World Health Organization. (2022). WHO European Regional obesity Report 2022. World Health Organization.

Wu, Y., Kemps, E., & Prichard, I. (2024). Digging into digital buffets: A systematic review of eating-related social media content and its relationship with body image and eating behaviours. Body Image,48(101650). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.101650

Yolcuoğlu, İ. Z., & Kızıltan, G. (2022). Effect of Nutrition Education on Diet Quality, Sustainable Nutrition and Eating behaviors among University students. Journal of the American Nutrition Association,41(7), 713–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2021.1955420

Yoshikawa, T., Orita, K., Watanabe, Y., & Tanaka, M. (2012). Validation of the Japanese version of the power of food scale in a young adult population. Psychological Reports,111(1), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.2466/08.02.06.15.PR0.111.4.253-265

Zeeni, N., Kharma, A., Malli, J., Khoury-Malhame, D., M., & Mattar, L. (2024). Exposure to Instagram junk food content negatively impacts mood and cravings in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Appetite,195(December 2023), 107209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2024.107209

Acknowledgements

We thank all students who agreed to participate in the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). This study was not funded or supported by governmental, commercial, or non-profit organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.D.B is the author who takes part in planning the entire flow of the study and participates in the conception design of the study. Data was collected by M.K.T, G.A.Y, S.S, D.G, and N.S. G.D.B performed the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the findings, drafting and revising the manuscript together with M.K.T. All authors have critically reviewed and agreed with the final version of the manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures were approved by the Marmara University Faculty of Health Science Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee with date and number 24.11.2022/106.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was provided by all participants in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dumlu Bi̇lgi̇n, G., Keküllüoğlu Tan, M., Yıldırım, G.A. et al. Elucidating the role of social media usage on eating behavior and hedonic hunger in college students: a cross-sectional design. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06350-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06350-5