Abstract

Among the global immigrant population, one of the fastest growing populations is the South Asian community. South Asian youth have experienced difficulties acculturating to the host culture. These difficulties have caused issues relating to identity and conflicts with family members relating to dating, marriage, and education. This scoping review will aim to summarize the literature available on acculturation and psychological well-being. The scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and Askey & O’Malley’s approach to data extraction. During the initial search, 220 full-text articles were retrieved from the APA PsycInfo, Web of Science, Medline, and Scopus databases. Ten articles were included in the final review. The following four themes were formulated: acculturation style, family conflict, coping style, and discrimination. We highlight that policies supporting collaboration between mental health practitioners, educators, researchers, and South Asian communities are critical for creating intervention programs that help South Asian families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As of 2022, there were 281 million immigrants worldwide, representing 3.6% of the global population (Mcauliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021). One of the fastest-growing immigrant populations is the South Asian community (ABS, 2022; South Asian Americans Leading Together, 2019). Within this population, South Asian adolescents and youth are at a higher risk of psychological distress compared to other immigrant populations (Anyon et al., 2014; Sam, 2010). South Asian youth have experienced difficulties acculturating to the host culture, leading to acculturative stress. These difficulties have led to issues relating to identity and conflicts with family members relating to dating, marriage, and education (Dey & Sitharthan, 2017). Researchers have attempted to understand the relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being among South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth. There has been one literature review on South Asian immigrant adolescents focusing on education in Britain (Ghuman, 2002). To our knowledge, there are no reviews on the relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being among South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth. Therefore, this review will improve our understanding of South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth experiences, reducing inequalities in mental health and encouraging their effective integration into society. The findings of this review will be beneficial to academics, policymakers, and practitioners who work with this community.

South Asian immigrant population

South Asian communities have migrated to first-world countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom for reasons such as refuge, education, and employment (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022; Canada, 2020; GOV.UK, 2022). This community includes countries such as Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, 2020). South Asian communities have similar cultural characteristics, such as strong relationships with their language and religion and a hierarchical structure in their family in which elderly members are highly respected (Tripathi & Mishra, 2016). Although previous research has shown differences between South Asian communities, these differences are due to demographic factors such as age and time in the host country (Belhadj Kouider et al., 2014). Due to cultural differences, South Asian immigrants are more likely to display stress after migrating to the host country (Khan & Watson, 2005; Nilaweera et al., 2014). Since migration involves abandoning the social ties from the native country, there is significantly low social support for immigrants in the host country (Khatiwada et al., 2021). To maintain mental and physical well-being, the South Asian population heavily relies on religious practices and social support from their community; this implies that within these families, customs, and traditions are perceived as more suitable for their needs compared to Western customs and traditions (Deepak, 2005; Foroutan, 2008; Lecompte et al., 2018).

Acculturation and psychological well-being

Immigrants often maintain aspects of their native country’s culture while also identifying with and adapting to the culture of their host country (Brown & Zagefka, 2011; Redfield et al., 1936). This phenomenon is called acculturation and can lead to behavioral or psychological changes in immigrants (Chirkov, 2009). Berry’s bidimensional framework is the most common acculturation theory (Brown & Zagefka, 2011). Berry identified four acculturation strategies: Assimilation (identifying mainly with the host country culture and disengaging with native country culture); Separation (identifying with the native country culture and overlooking the host country culture); Integration (identifying with both the native and host country cultures), and Marginalization (refusing to connect with both the native and host country cultures) (Berry, 1990). According to Berry’s (2003) framework, acculturation involves cultural and psychological levels. At a psychological level, acculturation involves behavior changes through dressing or speaking, and individuals will adopt an acculturation strategy (Berry & Sam, 2016). However, the acculturation process could be challenging to other immigrants and may lead to acculturative stress. According to this framework, an individual undergoes three types of adaptation (long-term changes in acculturation), which are psychological adaptation (measured through psychological well-being), sociocultural adaptation (measured through school adjustment), and intercultural adaptation (achieving successful intercultural relations) (Berry & Sam, 2016).

Researchers steadily study acculturation among immigrant adolescents and youth. Acculturation is vital for this age group as they experience physical and psychological changes. According to Erikson (1968), identity formation is critical to psychological development for adolescents and youth. Adolescents start to explore and question their identity, which includes who they are and want to be, the roles they want to play as adults, and their standing in society (Meeus et al., 2010). Furthermore, identity formation in adolescents and youth who are members of an ethnic minority would be more challenging due to being exposed to values and practices from both the host and native culture (Sodowsky et al., 1995). For this reason, we focused on immigrant adolescents and youth in this review.

Within the literature, acculturation impacts the psychological well-being of immigrant youth. There have been both positive and negative outcomes between acculturation and the psychological well-being of immigrant youth. Biculturalism, ethnic identity, and resilience promote psychological well-being (Balidemaj & Small, 2019; Phinney et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2018). Factors such as discrimination, family conflict, and acculturative stress, which is stress that arises from adapting to the culture of the host country, have been found to negatively impact the psychological well-being of immigrant youth and lead to psychological distress (Kirmayer et al., 2011; Sirin et al., 2013; Zetino et al., 2020). Furthermore, previous research has shown how immigrant youth experience more psychological distress than youth of majority background (Bas-Sarmiento et al., 2017). Psychological well-being has been measured through resilience, hedonic, and eudemonic well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryff, 1995). Hedonic well-being, known as subjective well-being, is defined as positive emotions and life satisfaction experienced by an individual, and eudemonic well-being is personal growth and self-meaning for an individual (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryff, 1995). While researchers have conducted a large body of research on the relationship between acculturation and the psychological well-being of immigrant youth (Hale & Kuperminc, 2021; Ren & Jiang, 2021), fewer studies have focused on South Asian youth (Dey & Sitharthan, 2017; Farver et al., 2002). We chose a scoping review to document the extent of the literature on the research topic (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Compared to a systematic review, a scoping review lets us map out our research topic’s fundamental concepts and look for literature gaps. To our knowledge this is the first scoping review on this population in relation to adolescents and youth. Therefore, the main aim of this review was to identify the factors affecting the relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being and the gaps in South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth.

Methodology

The scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and Arskey & O’Malley’s approach to data extraction (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Tricco et al., 2018).

Identifying the research question

The scoping review used the following research questions: what are the factors in the literature that affect the relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being in South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth? What are the gaps in the literature pertaining to the relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being among South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth?

Studies were included if they mentioned adolescents or youth. Acculturation is defined as individuals integrating aspects from other cultures after interacting with individuals of different cultures (Berry, 1990). Any measures or theories that use this definition of acculturation will be included in the research. The following concepts are used to define psychological well-being in the scoping review: (Mcauliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021) Hedonic well-being/subject well-being, including positive emotions and life satisfaction experienced by an individual (Brown & Zagefka, 2011; Diener et al., 2013); and eudemonic well-being, personal growth and self-meaning for an individual (Strelhow et al., 2020). Resilience is the ability to adjust or overcome a stressful situation (Crawford et al., 2006). Psychological distress is defined as anxiety and/or depressive symptoms presented by an individual or if the individual displays acculturative stress (Gong et al., 2016). Coping is defined as ‘the constantly changing cognitive & behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person’ (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 141).

Identifying the relevant studies

The following databases were used for the scoping review: PsycInfo, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus. The search was carried out by using the following keywords (refer to Appendix): (“asyl* or “newcomer” or “refuge* or “displaced person” or “migrant” or “immigrant”) and (“child* or “adolescen* or “young” or “minor” or “teenage* or “youth”) and (“psychiatr*” or “psycholog*” or “psychosocial” or “mental” or “wellbeing” or “trauma* or “PTSD” or “posttraumatic” or “stress” or “resilience” or “coping” or “adjustment” or “emotion” or “behavio#r” or “internalizing” or “externalizing” or “anxiety” or “depression”) and (“acculturat* or “assimilation* or “integration” or “marginali#ation” or “separation” or “adaptation”) and (South Asia* or India* or Sri lanka* or Pakistan* or Bangladesh* or “Bhutan” or Nepal* or “Maldives”).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: selected studies needed to explore the gap in the relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being and the factors that affect this relationship in South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth. The selected studies were also peer reviewed, written in English, and published from 2000 to 2022. This timeframe was selected because there was an increase in this population in first-world countries. The literature was required to include adolescents and youth from South Asian, migrant, refugee and/or asylum seeker backgrounds. Participants could have migrated from India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and/or the Maldives (SAARC, 2020). Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies were included in the review, and all the articles that met the full selection criteria were available online. Papers were excluded if they did not fit the inclusion criteria of the review. Papers that did not meet the research aims, needed an adequate research design, duplicated research, or needed more relevance to the research purposes were eliminated from the current review.

Study selection

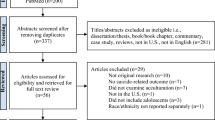

The literature review was carried out by two researchers and was managed using Endnote (20) and Covidence. First, each abstract was reviewed by both researchers to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. During the initial search, we retrieved 220 full-text documents (APA PsycInfo-52, Web of Science-92, Medline-61, Scopus-15). After 98 duplicates were removed and further screening was conducted by the first author. 10 articles were selected for inclusion in the final review (Fig. 1).

Results

Of the 10 studies selected (Table 1), two were conducted in Australia, Canada, and the United States, and one was conducted in each of the following countries: New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, and the United Kingdom. Seven studies used quantitative designs, while three studies used qualitative designs. Eight studies included adolescent and adolescent participants, while two studies used both adolescent/youth and parental participants. All the studies included South Asian participants; however, within these studies, six studies also included participants from other immigrant backgrounds.

Acculturation styles

Three studies found an association between participants’ acculturation style and psychological well-being (Bhui et al., 2005; Dey & Sitharthan, 2017; Farver, Bahadha & Narang, 2002). Integration was the most preferred style, while marginalization was the least favored (Abouguendia & Noels, 2001; Dey & Sitharthan, 2017). Young people choose an integrated acculturation style because they seek to belong to both cultures, and the host country’s acceptance of multiculturalism also plays a role (Dey & Sitharthan, 2017). More integrated participants were self-competent, had higher GPAs, had fewer in-group hassles, were less likely to be hit as a punishment by their parents, and had fewer depressive symptoms (Abouguendia & Noels, 2001; Bhui et al., 2008; Farver, Bahadha & Narang, 2002).

Pakistani and Indian youth with a marginalized acculturation style were vulnerable to acculturative stress (Dey & Sitharthan, 2017). A separate acculturation style was associated with depressive symptoms and low self-esteem in first-generation youth and depressive symptoms in second-generation youth (Abouguendia & Noels, 2001). However, a separation acculturation style was positively associated with life satisfaction in Pakistani adolescents (Sam, 2000). The authors noted that as youths adopt a separation acculturation style, they may interact only with their native culture, which may not allow them to compare themselves with adolescents from the majority background (Sam, 2000).

Family conflict

Three research studies found that conflict between parents and their children was a factor that affected the relationship between acculturation and the psychological well-being of South Asian immigrant youth. Conflicts occur between values among parents and their children, academic performance, and gender roles (Isalm et al., 2017; Renzaho et al., 2017; Sam, 2000). Within the South Asian population, there is an emphasis on the importance of education. South Asian families migrate to first-world nations such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia for career and academic opportunities and to provide further opportunities for their children (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). Therefore, parents have high expectations that their children will succeed in their education. Youths reported that they experienced pressure from their parents to do well in their academic studies. One study revealed that Muslim youth reported expectations to be religious, studious, and to perform household chores. This affected their psychological well-being as they experienced symptoms of anger and sadness. Another study noted that young people felt frustrated because their academic effort was not recognized and were consistently compared to the perfect student (Islam et al., 2017).

The differences in values between parents and youth created conflict between the generations. In most South Asian families, children are expected to choose a career as a lawyer, medical doctor, or engineer (Islam et al., 2017). Youths reported that their parents struggled to adapt to the host country’s values and abandoned traditional values (Renzaho et al., 2017). Due to the power dynamic, young people had to be responsible for acculturating to the host while maintaining their native culture. This allows parents to communicate with the host country’s culture through their children (Renzaho et al., 2017). This dynamic created tension, as young people had to take on additional responsibilities to care for their families and be cultural translators. One study noted that female youth struggle with the differences in values between their heritage and mainstream culture. For instance, female participants noted that they had conflicts with their parents when they interacted with male youth, as it was noted that in Indian culture, female and male youth were not allowed to interact with each other (Islam et al., 2017).

Coping

Three studies described coping as affecting acculturation and psychological well-being among South Asian youth (Islam et al., 2017; Tummala-Narra et al., 2016)—one coping mechanism involved seeking help from friends to manage acculturative stress. Participants felt more comfortable confiding in a friend with a similar ethnic or religious background, as they could connect (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). However, participants were reluctant to seek support from their parents, as their parents were perceived to be stressed about issues relating to finances, cultural differences, and loss of network from their native country (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). Another coping mechanism was seeking help from a guidance counselor or mental health professional. Participants reported that mental health professionals’ nonjudgmental approach helped participants share their stressful experiences (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). As a coping strategy, participants displayed resilience, such as showing appreciation for their education and work in the host country. Female participants reported gratitude for having the ability to choose their career path.

Furthermore, participants expressed gratitude for their parents’ difficulties in migrating and adjusting to the host culture (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). One of the studies reported that alcohol and drug use were other ways to cope with stress. Their religion prohibits Muslim youth from consuming alcohol and illicit substances. However, participants reported feeling unaffected by the consequences and explained that this was a way to rebel against South Asian traditions. Participants reported that because of their parents’ lack of understanding and openness to mental health support, drugs and alcohol use were the only methods used to cope with stress (Islam et al., 2017). A robust religious identity was found to be a coping mechanism among Muslim youth and acted as a shield against discrimination. Utilizing religious identity as a coping mechanism aligns with the rejection-identification model. This model posits that individuals identify strongly with their in-group to protect their self-esteem in response to negative evaluations from the out-group (Stuart & Ward, 2018).

Discrimination

Discrimination is another factor that affects acculturation and psychological well-being among South Asian youth (Neto, 2010; Stuart & Ward, 2018; Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). Participants in one study noted that they experienced discrimination at work, which affected their sense of belonging in the host country (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). These participants felt marginalized due to their language, religious practices, food, and association with the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Participants experienced discrimination through harassment, verbal slurs, and stereotyping (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). Participants’ experiences with discrimination also affected whether they would seek support from school when experiencing stress. Another study found that discrimination stress was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms among youth who did not have a religious identity. Hence, having a religious identity protects against discrimination (Stuart & Ward, 2018). Higher levels of ethnic behaviors and discrimination resulted in lower psychological well-being and less integration with mainstream society. This study noted that discrimination was a major acculturative stressor associated with lower adaptation in youth (Neto, 2010).

Discussion

This scoping review summarized the available literature on the relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being and the factors that affect this relationship for South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth. This is the first review on acculturation and psychological well-being in this population. Our study focuses on the unique experiences of South Asian youth in Western countries, in contrast to earlier reviews that have primarily addressed larger immigrant populations. In addition to highlighting important issues such as family conflict and discrimination, our review clarifies the coping strategies that promote resilience in this community. We provide insightful information through this review for academics, policymakers, and practitioners who want to create intervention programs and support services sensitive to cultural differences and cater to the requirements of this population.

Additionally, we can explain the significance of this relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being through Berry’s (2003) framework (Berry & Sam, 2016). According to this framework, acculturation is an interaction between an individual’s cultural and psychological levels. This involves psychological changes through behavioral changes such as eating or dressing, and if these changes are challenging, they can lead to acculturative stress in an individual. Second, individuals undergo psychological adaptation, measured through psychological well-being (Berry & Sam, 2016).

The review revealed that acculturation styles, family conflict, discrimination, and coping were some of the factors that affected the relationship between acculturation and psychological well-being among South Asian immigrant youth. According to the literature, integration is the most common acculturation style, while marginalization is the least common among young people (Abouguendia & Noels, 2001; Dey & Sitharthan, 2017). Furthermore, a review showed that an integration acculturation style was associated with positive outcomes in participants (Abouguendia & Noels, 2001; Bhui et al., 2008; Farver, Bahadha & Narang, 2002). This finding supports Berry’s acculturation model, which states that integration is the most adaptive acculturation style (Berry & Sam, 1997).

Family conflict and discrimination negatively impacted the participants’ well-being (Neto, 2010; Renzaho et al., 2017; Stuart & Ward, 2018; Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). Family conflict was another factor affecting the participants’ acculturation and psychological well-being. Conflicts mainly occur due to cultural differences between children and their parents, called an ‘acculturation gap’ (Costigan & Dokis, 2006). Children raised outside their native culture or country may experience a different upbringing from their parents (Birman, 2006). Education is an essential pillar of South Asian culture.

For this reason, many South Asian families migrate to first-world nations to provide further opportunities and education for their children (Karasz et al., 2019). Therefore, parents might put more pressure on their children to succeed in their education. Furthermore, parents might be unable to participate in the broader community due to the responsibility of maintaining family and community ties. Therefore, this approach might widen the acculturation gap between parents and their children, leading to more conflict. Participants experienced discrimination through harassment, verbal slurs, and stereotyping (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). Participants’ experiences with discrimination also affected whether they would seek support from school when experiencing stress. This finding shows how discrimination negatively impacts the well-being of South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth.

Family and school intervention programs are recommended to combat discrimination and family conflict (Islam et al., 2017; Renzaho et al., 2017; Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). An intergenerational approach is needed to build communication between parents and their children, leading to less conflict. Family interventions may help mothers with postpartum depression and reduce family conflict. Youth in this study noted that mothers’ untreated depression caused issues in their parenting (Islam et al., 2017). School intervention programs might reduce the discrimination experienced by South Asian students. Teachers and school administrations can create a more inclusive environment for immigrant students with appropriate training. Home-school collaboration facilitates cross-cultural learning, which is advantageous for students, families, and faculty. Schools can help with resettlement for immigrant families if they work with parents to use their skills to engage with their children, which could lead to positive experiences (Miller et al., 2021). This research emphasizes how critical it is for policymakers to consider culturally sensitive training when implementing mental health services and educational settings. Furthermore, policies that support collaboration between mental health practitioners, educators, researchers, and South Asian communities are critical for creating intervention programs that help South Asian families (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016).

Participants coped by seeking support from friends, mental health professionals, drugs, and alcohol (Islam et al., 2017; Stuart & Ward, 2018; Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). A few participants displayed resilience by showing appreciation for opportunities in the host country (Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). These results show that although participants experience acculturative stress, they seek support from both cultures to develop their bicultural identity. This is important, as having a bicultural identity has been linked to better self-esteem and optimism (Schwartz et al., 2015).

Longitudinal research with a larger and more diverse sample size is recommended for future research, as this type of research can provide an in-depth understanding of acculturative experiences (Neto, 2010; Stuart & Ward, 2018; Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). The drawback of using cross-sectional research is that it captures behavior at one point, which challenges the generalizability of the results. Acculturation is a complicated process that affects immigrants throughout their lifetime and is more important for adolescents and young people because it shapes their identity. Therefore, longitudinal research could capture how acculturation affects participants at different points in their lives. It would be interesting to see how the level of acculturation and acculturation style change during migration and how acculturation affects well-being at different points in people’s lives. However, there may be challenges in implementing longitudinal research. As most longitudinal studies use panel data, there might be difficulties in tracking participants who drop out for various reasons.

The sample size was an issue for most studies. One study noted that mental health service users influenced the sample size. Furthermore, there were more female participants than male participants. This could be due to different upbringings since men are typically taught not to communicate honestly (Islam et al., 2017). Most related research included a sample of first-generation or second-generation adolescents and youth (Dey & Sitharthan, 2017; Farver, Bahadha & Narang, 2002; Stuart & Ward, 2018; Tummala-Narra et al., 2016). Including adolescents and youths from the first, second, and third generations may be necessary to understand acculturation’s impact on their psychological well-being and the differences between generations.

Furthermore, the authors noted that the studies’ results may reflect the participants’ location. Therefore, the generalizability of the results is low (Dey & Sitharthan, 2017; Farver, Bahadha & Narang, 2002). Using a sample from different continents may be beneficial for examining the differences in the effects of acculturation on each sample group (Bhattacharya, 2011).

Limitations

This review has a few limitations. The review focused on peer-reviewed articles written in English and, therefore, had missed gray literature or articles in other languages, which provided additional insight. This review focused on adolescents and youth; a further focus on parents and their children might provide insight into how acculturation impacts the family. It is important to note that only three studies primarily used a South Asian sample. In contrast, other studies in the review included participants from different immigrant backgrounds, which might have affected the results. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with some caution.

Conclusion

Over the years, there has been an increase in South Asian immigrants in first-world nations. Within the past literature, South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth have experienced difficulties with acculturation and their psychological well-being. This research sets out to identify the gaps and factors that affect acculturation and psychological well-being among South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth. This review showed that additional research on South Asian families is needed to fill this gap. Furthermore, policies that support collaboration between mental health practitioners, educators, researchers, and South Asian communities are critical for creating intervention programs that help South Asian families. Future research should implement longitudinal research with a diverse sample to investigate the effects of acculturation on South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Abouguendia, M., & Noels, K. A. (2001). General and acculturation-related daily hassles and psychological adjustment in first‐and second‐generation south Asian immigrants to Canada. International Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590042000137

Anyon, Y., Ong, S. L., & Whitaker, K. (2014). School-based mental health prevention for Asian American adolescents: Risk behaviors, protective factors, and service use. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5(2), 134. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035300

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Toward a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022). Australia’s population by country of birth. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/australias-population-country-birth/latest-release

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2021–2022). Overseas migration. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/overseas-migration/2021-22-financial-year

Balidemaj, A., & Small, M. (2019). The effects of ethnic identity and acculturation in mental health of immigrants: A literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 65(7–8), 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019867994

Bas-Sarmiento, P., Saucedo-Moreno, M. J., Fernández-Gutiérrez, M., & Poza-Méndez, M. (2017). Mental health in immigrants versus native population: A systematic review of the literature. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 31(1), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.07.014

Belhadj Kouider, E., Koglin, U., & Petermann, F. (2014). Emotional and behavioral problems in migrant children and adolescents in Europe: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(6), 373–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0485-8

Berry, J. W. (1990). Acculturation and adaptation: A general framework. In W. H. Holtzman & T. H. Bornemann (Eds.), Mental health of immigrants and refugees (pp. 90–102). Hogg Foundation for Mental Health.

Berry, J. W., & Sam, D. L. (1997). Acculturation and adaptation. Handbook of cross-cultural Psychology, 3(2), 291–326.

Berry, J. W., & Sam, D. L. (2016). Theoretical perspectives. In D. L. Sam & J. W. Berry (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (2 ed., pp. 11–29). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316219218.003

Bhattacharya, G. (2011). Global contexts, social capital, and acculturative stress: experiences of Indian immigrant men in New York City [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 13(4), 756-765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-011-9444-y

Bhui, K., Stansfeld, S., Head, J., Haines, M., Hillier, S., Taylor, S., Viner, R., & Booy, R. (2005). Cultural identity, acculturation, and mental health among adolescents in East London’s multiethnic community. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(4), 296–302.

Bhui, K., Khatib, Y., Viner, R., Klineberg, E., Clark, C., Head, J., & Stansfeld, S. (2008). Cultural identity, clothing and common mental disorder: A prospective school-based study of white British and Bangladeshi adolescents [Article]. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(5), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.063149

Birman, D. (2006). Acculturation gap and family adjustment: Findings with soviet jewish refugees in the United States and implications for measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(5), 568–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106290479

Brown, R., & Zagefka, H. (2011). The dynamics of acculturation: An intergroup perspective. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 44, pp. 129–184). Elsevier.

Canada, S. (2020). Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm

Chirkov, V. (2009). Critical psychology of acculturation: What do we study and how do we study it, when we investigate acculturation? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(2), 94–105.

Costigan, C. L., & Dokis, D. P. (2006). Relations between parent–child acculturation differences and adjustment within immigrant Chinese families. Child Development, 77(5), 1252–1267.

Crawford, E., Wright, M., & Masten, A. S. (2006). Resilience and spirituality in youth. The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence, 355–370.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1

Deepak, A. C. (2005). Parenting and the process of migration: Possibilities within south asian families. Child Welfare, 84(5), 585–606. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45398734

Dey, P., & Sitharthan, G. (2017). Acculturation of Indian subcontinental adolescents living in Australia. Australian Psychologist, 52(3), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12190

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Oishi, S. (2013). Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030487

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton & Company.

Farver, J. A. M., Bhadha, B. R., & Narang, S. K. (2002). Acculturation and psychological functioning in Asian Indian adolescents [Article]. Social Development, 11(1), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00184

Foroutan, Y. (2008). Gender, religion and work: Comparative analysis of south Asian migrants. Fieldwork in Religion, 3(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1558/firn.v3i1.29

Ghuman, P. S. (2002). South-Asian adolescents in British schools: A review. Educational Studies, 28(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690120090370

Gong, Y., Palmer, S., Gallacher, J., Marsden, T., & Fone, D. (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environment International, 96, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.019

GOV.UK. (2022). Population of England and Wales. Office for National Statistics. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest

Hale, K. E., & Kuperminc, G. (2021). The associations between multiple dimensions of acculturation and psychological distress among latinx youth from immigrant families. Youth & Society, 53(2), 342–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X19898698

Islam, F., Multani, A., Hynie, M., Shakya, Y., & McKenzie, K. (2017). Mental health of south Asian youth in Peel Region, Toronto, Canada: A qualitative study of determinants, coping strategies and service access. British Medical Journal Open, 7(11), e018265. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018265

Karasz, A., Gany, F., Escobar, J., Flores, C., Prasad, L., Inman, A., Kalasapudi, V., Kosi, R., Murthy, M., & Leng, J. (2019). Mental health and stress among South asians. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(1), 7–14.

Khan, S., & Watson, J. C. (2005). The Canadian immigration experiences of Pakistani women: Dreams confront reality. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 18(4), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070500386026

Khatiwada, J., Muzembo, B. A., Wada, K., & Ikeda, S. (2021). The effect of perceived social support on psychological distress and life satisfaction among Nepalese migrants in Japan. PloS One, 16(2), e0246271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246271

Kirmayer, L. J., Narasiah, L., Munoz, M., Rashid, M., Ryder, A. G., Guzder, J., Hassan, G., Rousseau, C., & Pottie, K. (2011). Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: General approach in primary care. Cmaj, 183(12), E959–E967. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090292

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company.

Lecompte, V., Miconi, D., & Rousseau, C. (2018). Challenges related to migration and child attachment: A pilot study with south Asian immigrant mother–child dyads. Attachment & Human Development, 20(2), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2017.1398765

McAuliffe, M., & Triandafyllidou, A. (Eds.). (2021). World Migration Report 2022. International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva. https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022

Meeus, W., Van De Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., Schwartz, S. J., & Branje, S. (2010). On the progression and stability of adolescent identity formation: A five-wave longitudinal study in early‐to‐middle and middle‐to‐late adolescence. Child Development, 81(5), 1565–1581.

Miller, E., Ziaian, T., Baak, M., & de Anstiss, H. (2021). Recognition of refugee students’ cultural wealth and social capital in resettlement. International Journal of Inclusive Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1946723 (UniSA Education Futures).

Neto, F. (2010). Predictors of adaptation among adolescents from immigrant families in Portugal [Empirical study; quantitative study]. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41(3), 337–454. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.41.3.437

Nilaweera, I., Doran, F., & Fisher, J. (2014). Prevalence, nature and determinants of postpartum mental health problems among women who have migrated from south Asian to high-income countries: A systematic review of the evidence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 166, 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.021

Phinney, J. S., Horenczyk, G., Liebkind, K., & Vedder, P. (2001). Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 493–510.

Redfield, R., Linton, R., & Herskovits, M. J. (1936). Memorandum for the study of Acculturation. American Anthropologist, 38(1), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1936.38.1.02a00330

Ren, Q., & Jiang, S. (2021). Acculturation stress, satisfaction, and frustration of basic psychological needs and mental health of Chinese migrant children: Perspective from basic psychological needs theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094751

Renzaho, A. M., Dhingra, N., & Georgeou, N. (2017). Youth as contested sites of culture: The intergenerational acculturation gap among new migrant communities-Parental and young adult perspectives [Empirical Study; Interview; Focus Group; Qualitative Study]. PLoS ONE, 12(2), ArtID e0170700 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170700

Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(4), 99–104.

Sam, D. L. (2000). Psychological adaptation of adolescents with immigrant backgrounds. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540009600442

Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., Benet‐Martínez, V., Meca, A., Zamboanga, B. L., Lorenzo‐Blanco, E. I., Rosiers, S. E. D., Oshri, A., & Sabet, R. F. (2015). Longitudinal trajectories of bicultural identity integration in recently immigrated hispanic adolescents: Links with mental health and family functioning. International Journal of Psychology, 50(6), 440–450. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12196

Sirin, S. R., Ryce, P., Gupta, T., & Rogers-Sirin, L. (2013). The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 736. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028398

Sodowsky, G. R., Kwan, K.-L. K., & Pannu, R. (1995). Ethnic identity of Asians in the United States. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 123–154). Sage Publications, Inc.

South Asian Americans Leading Together (2019). A demographic snapshot of South Asians in the United States. Retrieved from https://saalt.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/SAALT-Demographic-Snapshot-2019.pdf

South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation. (2020). About SAARC. https://www.saarc-sec.org/index.php/about-saarc/about-saarc

Strelhow, M. R. W., Sarriera, J. C., & Casas, F. (2020). Evaluation of well-being in adolescence: Proposal of an integrative model with hedonic and eudemonic aspects. Child Indicators Research, 13(4), 1439–1452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09708-5

Stuart, J., & Ward, C. (2018). The relationships between religiosity, stress, and mental health for muslim immigrant youth. Mental Health Religion & Culture, 21(3), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2018.1462781

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., & Weeks, L. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Tripathi, R. C., & Mishra, R. (2016). Acculturation in South Asia. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology, 337–354.

Tummala-Narra, P., Deshpande, A., & Kaur, J. (2016). South Asian adolescents’ experiences of acculturative stress and coping. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(2), 194. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000147

Wu, Q., Ge, T., Emond, A., Foster, K., Gatt, J. M., Hadfield, K., Mason-Jones, A. J., Reid, S., Theron, L., & Ungar, M. (2018). Acculturation, resilience, and the mental health of migrant youth: A cross-country comparative study. Public Health, 162, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.05.006

Zetino, Y. L., Galicia, B. E., & Venta, A. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences, resilience, and emotional problems in Latinx immigrant youth. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113450

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This review was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The idea for the article, data analysis and the manuscript was written by Tirani Kodippili. Tahereh Ziaian and Teresa Puvimanasinghe provided input on the design of the literature search. The literature review was carried out by Tirani Kodippili and Teresa Puvimanasinghe. Tahereh Ziaian, Teresa Puvimanasinghe, Adrian Esterman and Yvonne Clark provided feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This review paper is a part of PhD research project. This project was approved by the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval date: 27th October 2022, Project number 204931).

Competing interests

There are no relevant financial or non-financial interests of the authors to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

APA PsycInfo

Filters: Peer reviewed, Human, English language, 2000 to 2022

(asyl* or newcomer or refuge* or displaced person or migrant or immigrant) AND (child* or adolescen* or young or minor or teenage* or youth) AND (psychiatr* or psycholog* or psychosocial or mental or wellbeing or trauma* or PTSD or posttraumatic or stress or resilience or coping or adjustment or emotion or behavio#r or internalizing or externalizing or anxiety or depress* or life satisfaction) AND (acculturate* or assimilation* or integration or marginali#ation or separation or adaptation) AND (South Asia* or Indian subcontinent or India* or Sri Lanka* or Pakistan* or Bangladesh* or Bhutan or Nepal* or Maldives)

Web of Science

Filters: Document types: articles 2000-01-01 to 2022-08-01

TS=(asyl* OR newcomer OR refuge* OR displaced person OR migrant or immigrant) AND TS=(child* OR adolescen* OR young OR minor OR teenage* OR youth) AND TS=(psychiatr* OR psycholog* OR psychosocial OR mental OR wellbeing OR trauma* OR PTSD OR posttraumatic OR stress OR resilience OR coping OR adjustment OR emotion OR behavior OR internalizing OR externalizing OR anxiety OR depress* OR life satisfaction) AND TS=(acculturate* OR assimilation* OR integration OR marginalization OR separation OR adaptation) AND TS=(South Asia* OR Indian subcontinent OR India* OR Sri lanka* OR Pakistan* OR Bangladesh* OR Bhutan OR Nepal* OR Maldives)

Medline

Filters: English, Humans, 2000 to 2022

(asyl* or newcomer or refuge* or displaced person or migrant or immigrant) AND (child* or adolescen* or young or minor or teenage* or youth) AND (psychiatr* or psycholog* or psychosocial or mental or wellbeing or trauma* or PTSD or posttraumatic or stress or resilience or coping or adjustment or emotion or behavio#r or internalizing or externalizing or anxiety or depress* or life satisfaction) AND (acculturate* or assimilation* or integration or marginali#ation or separation or adaptation) AND (South Asia* or Indian subcontinent or India* or Sri Lanka* or Pakistan* or Bangladesh* or Bhutan or Nepal* or Maldives)

Scopus

Filters: Article, Journal, English

TITLE-ABS-KEY (asyl* OR newcomer OR refuge* OR displaced AND person OR migrant OR immigrant AND child* OR adolescen* OR young OR minor OR teenage* OR youth AND psychiatr* OR psycholog* OR psychosocial OR mental OR wellbeing OR trauma* OR ptsd OR posttraumatic OR stress OR resilience OR coping OR adjustment OR emotion OR behavior OR internalizing OR externalizing OR anxiety OR depress* OR "life satisfaction" AND acculturate* OR assimilation* OR integration OR marginalization OR separation OR adaptation AND "south asia" OR “Indian subcontinent” OR india* OR "sri lanka" OR pakistan* OR bangladesh* OR bhutan OR nepal* OR maldives) AND PUBYEAR > 1999 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, "ar" ) ) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, "English" ) ) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE, "j" ) )

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kodippili, T., Ziaian, T., Puvimanasinghe, T. et al. The impact of acculturation and psychological wellbeing on South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth: a scoping review. Curr Psychol 43, 21711–21722 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05981-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05981-y