Abstract

Shame has been considered a core component of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology. However, literature concerning the emotion regulation processes that underlie the association between these two constructs seems to be scarce. Therefore, the main aim of this cross-sectional study was to explore the role that mindfulness and body image-related cognitive fusion has on the relationship between the experience of shame and body dysmorphia-related symptomatology Additionally, biological sex differences concerning the studied variables were explored. Three hundred and twenty-seven participants (male and female) above 18 years old completed an online survey with self-report measures to assess shame experiences, mindfulness, body image-related cognitive fusion and body dysmorphia-related symptoms. Results indicated that female participants presented higher body dysmorphia-related symptomatology when compared with males. A path analysis was conducted suggesting that, while controlling for the effect of age and BMI, the experience of shame had a direct effect on body dysmorphia-related symptomatology, as well as an indirect effect through mindfulness and body image-related cognitive fusion. This model presented a good fit, explaining 56% of the variance of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology. Also, findings from a multi-group path analysis revealed that the relationship between these variables is invariant across males and females. These findings have important research and clinical implications, supporting the importance of targeting mindfulness and cognitive defusion skills when working in the context of Body Dysmorphia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Body dysmorphia, previously referred to as “dysmorphophobia”, a term first used by Enrico Morselli in 1891 (Morselli, 1891), has been described throughout history as a distressing concern about imagined flaws in one’s appearance (Bjornsson et al., 2010). Now recognized as a mental disorder (APA, 2013), Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) is a significantly impairing condition, characterized by an excessive preoccupation or obsession with a perceived/exaggerated defect in the physical appearance, that is unobservable or appears slightly to others (APA, 2013). The symptoms are associated with the performance of time-consuming and even dangerous compulsions (e.g., mirror checking, reassurance seeking, skin picking), as well as avoidance behaviors (e.g., in social situations where their perceived flaws can be noticed; APA, 2013).

BDD is a mental disorder that often begins in the adolescent years (Bjornsson et al., 2013; Phillips et al., 2005) and various risk factors are hypothesized for its development, such as a perfectionist or anxious temperament, experiences of abuse and neglect, bullying, history of physical humiliations or appearance-based teasing (Didie et al., 2006; Veale, 2004; Weingarden et al., 2017).

Previous studies have found that BDD prevalence rates range from 1,7% to 2,4% (APA, 2013; Brohede et al., 2015; Koran et al., 2008; Rief et al., 2006). However, the real prevalence of this disorder may be much higher since evidence has shown that BDD is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed (Schulte et al., 2020; Veale et al., 2016). Difficulties associated with the diagnostic of BDD may be due to the poor insight of individuals who suffer from this disorder. People with BDD tend to resort to medical procedures (specifically dermatological, cosmetic, and orthognathic) as an attempt to correct their perceived flaws, rather than seeking mental health-related professionals (Jassi & Krebs, 2021; Veale et al., 2016). Despite this, patients are often displeased with the procedures performed, leading to the persistency of body dysmorphia-related symptoms (Phillips et al., 2005; Veale et al., 2016). Furthermore, most health-related professionals are still unfamiliar with the symptoms and clinical manifestations of this disorder, failing to direct patients to adequate treatment (Veale et al., 2016). Lastly, many BDD sufferers conceal their symptoms due to shame or embarrassment, making it difficult to reach the correct diagnosis (Jassi & Krebs, 2021; Schulte et al., 2020; Veale et al., 2016).

BDD presents high comorbidity with Major Depressive Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Substance-Related Disorders, Avoidant Personality Disorder, and eating disorders, such as Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa (APA, 2013; Didie et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2002; Ruffolo et al., 2006). Besides, several studies revealed that BDD is associated with high rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, with approximately 80% of individuals with such disorder reporting past or current suicidal ideation (APA, 2013; Bjornsson et al., 2010; Phillips, 2007). Research has shown that even subclinical BDD or partial symptoms may have a significant negative impact on individuals’ physical and mental health, being equally worthy of attention (Altamura, 2001).

The universal experience of shame

Throughout the years, literature has revealed an association between body dysmorphic symptomatology and shame, describing it as the “core” component of the disorder (Clerkin et al., 2014; Veale, 2004; Veale & Gilbert, 2014; Weingarden et al., 2018). Indeed, recent cross-sectional studies have confirmed the high association between shame and BDD or dysmorphic concerns, in both clinical and community samples (e.g., Coimbra et al., 2023; Malcolm et al., 2021; Weingarden et al., 2017). Shame can be defined as a universal, multifaceted, and painful human experience that gains relevance in the development of one’s sense of self and identity as a social agent, while influencing interpersonal and moral behaviors (Gilbert, 2007; Gilbert & Andrews, 1998). According to Gilbert’s biopsychosocial model (Gilbert, 1998, 2007), shame comprises two different dimensions: external shame, when the attention is externally directed, involving the perception of being negatively judged by others; and internal shame, when the attention turns inwards and is focused on a negative image of the self in its own eyes (Gilbert, 1998, 2007). Since the exhibit of an attractive appearance is an important indicator of social attractiveness, body image gains a central role in the experience of shame and it is likely that shame will be triggered by the belief that one’s appearance is flawed (Gatward, 2007; Weingarden & Renshaw, 2015). This excessive preoccupation or obsession with a perceived physical defect that appears unobservable to others prevents the individual from accepting and being in the present moment, i.e., being mindful.

Mindfulness and body dysmorphia-related symptomatology

Mindfulness emerges as a result of being aware of the present moment by intentionally paying attention to it in a non-reactively and non-judgmentally manner, eliciting a “mindful emotion regulation”, a unique form of emotion regulation (Guendelman et al., 2017; Kabat-Zinn, 2015).

Being mindful seems to contrast with a critical self-focused attention and with appearance comparison, as well as with the emotion-related reactions that characterize BDD (Roberts, 2019). However, research on the relationship between mindfulness and BDD have reached contradictory conclusions (Lavell et al., 2018; Roberts, 2019). On one hand, specific facets of mindfulness, such as being aware of the present moment and being non-judgmental, were associated with lower BDD symptomatology. On the other hand, other facets, such as observing the present experience, were associated with higher BDD symptoms. Studies hypothesized that, when applied to non-meditators, the component of mindful observation is often unrelated to psychological health or associated with distress or dysfunction (Greco et al., 2011).

Hence, these contradictory findings have been hypothesized as being due to the difficulties in the assessment of mindfulness and support the need of further developing research in this topic (Bergomi et al., 2013: Greco et al., 2011).

The important role of body image-related cognitive fusion

The concept of cognitive fusion translates one’s entanglement with their internal experiences (thoughts, sensations, memories, emotions), and assumes them as the absolute truth, letting them dominate their behavior, it results in what is designated as cognitive fusion (Gillanders et al., 2014; Harris, 2009). When one is fused with their internal experiences, one considers them true descriptions of reality as opposed to subjective and transitory experiences (Hayes et al., 2006, 2012). This process is conflicting with having a mindful attitude, since it increases the tendency to avoid one’s internal experience (Hayes & Wilson, 2006).

When these internal experiences revolve around one’s body image, as in the case of BDD, a specific dimension of cognitive fusion emerges - body image-related cognitive fusion (Ferreira & Trindade, 2015). Research suggests that becoming fused with unwanted thoughts tends to be associated with avoidance-driven responses, leading to an increase of personal anguish and overall suffering (Hayes et al., 2006).

In the context of BDD, these maladaptive responses can present themselves as: seeking cosmetic procedures to camouflage perceived defects; avoiding social contexts that expose perceived flaws; or use potentially dangerous substances to try to change certain body parts. Also, cognitive fusion has been related to resistance in behavior change, even whilst the individual understands these changes as desirable and beneficial (Forman & Butryn, 2015).

Body image-related cognitive fusion has been previously proved to be a relevant construct in the context of body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and psoriasis (Almeida et al., 2020; Ferreira & Trindade, 2015; Trindade & Ferreira, 2014) and, though it seems to be an equally relevant construct to the understanding of BDD-related symptoms, no studies to date have been published regarding this relationship.

Study aims and main hypotheses

The main aim of this study was to clarify the role of mindfulness and body image-related cognitive fusion in the relationship between shame and body dysmorphia symptomatology, while controlling for the effect of age and BMI. BMI has been reported as a relevant variable in the study of body image-related cognitive fusion (e.g., Ferreira & Trindade, 2015) and age has had mixed results regarding its relationship with body dysmorphia symptomatology (e.g., Haider et al., 2023; Matos et al., 2023). It was hypothesized that individuals who presented higher levels of shame would tend to present higher levels of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology, and that this relationship would be partially explained by an inability to be mindful and a higher tendency to be entangled in one’s own body image-related internal experiences. The model plausibility is expected for both males and females. In addition, this study also aimed to explore potential differences between males and females regarding BDD symptomatology, since previous research has been inconsistent in this topic (Bjornsson et al., 2010; Koran et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2006).

Methods

Participants

The sample included 327 participants from the general population, both male and female, aged between 18 and 64 years old (M = 27.98; SD = 10.26), with a mean of 14.57 (SD = 2.60) years of education. Concerning their area of residence, 38.5% of participants resided in an urban area, 24.2% in a semi-urban area and 37.3% in a rural area. Most participants (79.8%) were single, while 17.1% were married or in a long-term relationship, 2.8% were separated or divorced and 0.3% were widowed. The participants’ Body Mass Index (BMI) ranged from 15.94 kg/m² to 40.90 kg/m², with 8.26% of the participants being considered underweight, 68.50% presenting normal weight, 17.12% being considered overweight, 4.59% presenting Class I Obesity, 1.22% presenting Class II Obesity, and 0.31% presenting Class III Obesity, which is equivalent to the normal distribution for Portuguese population (Poinhos et al., 2009). The mean of the participants’ BMI was of 23.08 kg/m² (SD = 3.95), which corresponds a normal weight range (World Health Organization, 1995).

Regarding demographic characteristics, the two groups (male and female) presented statistically significant differences regarding: age (t(325) = -2.788; p = .006), civil status (χ2(3) = 16.345; p = .001), and BMI (t(325) = 2.645; p = .009). No significant differences were observed between male and female in regard of: years of education (t(325) = − 0.365; p = .715) and area of residence (χ2(2) = 0.371; p = .831).

Procedures

This study was developed in the context of a wider comprehensive research project investigating body dysmorphia in the Portuguese population (Body Dysmorphia: A comprehensive study in the Portuguese population), approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra. Thus, the research and data collection protocol followed the ethical requirements stipulated by said educational institution.

Participants became aware of the present study through online advertisements in several social networks and were also asked to share the study with two or more friends older than 18 years old (Snowball Sampling Method). By clicking the link advertised online, participants accessed a consent document which properly informed them about the aims of the study and the anonymous and voluntary nature of their participation, as well as the purpose and confidentiality of the collected data. To enter the study, participants were required to sign the inform consent.

Three hundred and ninety-three participants (299 females, 91 males and 3 people who chose not to disclose their biological sex) from the Portuguese general population completed the self-report protocol (15–20 min approximately), with age ranging from 18 to 68 years old. Participants’ exclusion criteria were: (a) age above 65 years old; (b) not being able to read, write or understand Portuguese; (c) not providing current weight or choosing not to disclose their biological sexFootnote 1 and (d) receiving psychological and/or psychiatric support at the moment. According to these criteria, 16.79% of the original sample (66 individuals) was excluded.

Measures

Demographic data

The first step of the protocol included a self-report questionnaire to assess participants’ sociodemographic data (e.g., age, area of residence, educational level, marital status, biological sex, height, and current weight) and clinical information (e.g., current psychological or psychiatric support).

Body mass index (BMI)

BMI was calculated by dividing the participants’ self-reported current weight (kg) by height squared (m).

External and internal shame scale – (EISS; Ferreira et al., 2020)

The EISS is a self-report scale, comprised by 8 items, designed to measure shame in its two distinct focal dimensions: external shame and internal shame. The items (e.g., “I feel that other people don’t understand me”; “I feel that I am unworthy as a person”) are scored on a five-point Likert scale (from 0 = Never to 4 = Always), with higher scores reflecting higher levels of shame. In its validation study, the instrument revealed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89, whereas in the present study the EISS showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91.

Child and adolescent mindfulness measure (CAMM; Greco et al., 2011; Cunha et al., 2013)

The CAMM is a 10-item scale designed to measure mindfulness skills. Even though it was validated with school-aged children and adolescents in mind, it presented itself as a valid instrument for the adult population as well. The items (e.g., “I tell myself that I shouldn’t feel the way I’m feeling”) are scored on a five-point Likert scale (from 0 = Never to 4 = Always), in which higher scores reflect more mindfulness skills. The CAMM showed an internal consistency of 0.80, in both its original and Portuguese validation studies. In the present study, CAMM presented an internal consistency of 0.88.

Cognitive fusion questionnaire - body image (CFQ-BI; Ferreira et al., 2015)

The CFQ-BI consists of 10 items developed to measure cognitive fusion concerning body image. Participants responded to the items (e.g., “My thoughts regarding my body image distract me from what I’m doing at that moment.”) on a seven-point Likert scale (from 1 = Never true to 7 = Always True), in which higher scores indicate higher levels of body image-related cognitive fusion. In its original Portuguese study, the CFQ-BI showed very good psychometric characteristics, including very good internal reliability (α = 0.96). In the present study, the CFQ-BI presented a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.98.

Dysmorphic concern questionnaire - P (DCQ-P; Oosthuizen et al., 1998; Coimbra et al., 2023)

The DCQ-P is a self-report questionnaire that comprises 7 items and is designed to measure individuals’ dysmorphic concern, meaning the degree of excessive concern about perceived defects in the physical appearance (Oosthuizen et al., 1998). The items (e.g., “Have you ever spent a lot of time worrying about a flaw in your appearance/bodily function?”) are measured according to a four-point Likert Scale (from 0 = Not at all to 3 = Much more than most people), with higher scores reflecting higher dysmorphic concern. In its original study, the instrument showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 In its original study, the instrument showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, while in its Portuguese validation study it showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90. In the present study, the DCQ-P showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91.

Data analysis

Data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 23.0; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL) and the Analysis of Moment Structures software (AMOS, version 22.0; IBM® SPSS® Amos™ 22; Arbuckle, 2013). To analyze the sample’s characteristics, descriptive statistics (such as the means and standards deviations) were calculated. In addition, differences between groups (male and female) regarding the study’s variables (age, BMI, shame, mindfulness, body image-related cognitive fusion and body dysmorphic symptomatology) were calculated through independent t-tests. Effect size was calculated through Cohen’s d, where effect sizes between 0.20 and 0.40 were considered small; between 0.50 and 0.70 were considered moderate effects and equal to or above 0.80 were considered strong effects (Cohen, 1998).

Furthermore, Pearson correlation coefficients were performed to explore the different associations between age, BMI, shame (EISS), mindfulness (CAMM), body image-related cognitive fusion (CFQ-BI) and body dysmorphia-related symptomatology (DCQ-P). According to Cohen’s guidelines, magnitudes between 0.10 and 0.30 are considered weak, between 0.30 and 0.50 are considered moderate and magnitudes equal to or above 0.50 are considered strong (Cohen et al., 2003).

To test the mediating effects of CAMM and CFQ-BI in the association between EISS and DCQ-P, a path analysis was performed. To calculate all model path coefficients and fit statistics, the Maximum Likelihood method was used. To evaluate the plausibility of the model, various goodness-of-fit measures were conducted, such as: Chi-Square (χ²), with a non-significant value (p > .50) indicating a good model fit; the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI), where values above 0.95 indicate a very good fit (Kline, 2011); and the Root-Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with values below 0.08 and p > .05 demonstrating a good model adjustment, with a 95% confidence interval (CI; Arbuckle, 2013).

To analyze the significance of the mediational paths, the Bootstrap procedure was conducted with 5000 resamples and 95% bias-corrected CI around the standardized estimates of total, direct and indirect effects. The effects are considered statistically significant (p < .05) when zero is not included in the interval between the lower and the upper limits of the 95% bias-corrected CI (Kline, 2011). Finally, to test the (in)variance of the structural model for both groups (male and female), a multi-group analysis was conducted. Invariance tests are a series of hierarchical models, tested by increasing levels of cross-group equality constraints. For the purpose of this study, configural and metric invariance were conducted to explore differences in the structural coefficients across the two groups (male and female).

Results

Preliminary data analysis

Normality of the distribution was assessed by the analysis of the values of Skewness (Sk) and Kurtosis (Ku), with Skewness values ranging from − 0.01 (CAMM) to 1.59 (age) and Kurtosis values ranging from 0.18 (DCQ-P) to 2.11 (BMI). These scores suggested that there was no severe violation of normal distributions (Sk < |3| and Ku < |8–10|; Kline, 2011).

Between group comparisons

Independent t-tests were performed to analyze differences between groups. Results indicated that the two groups did not present significant differences concerning EISS and CAMM. Alternatively, results revealed that, when compared to males, females had significant higher levels of CFQ-BI and DCQ-P. Regarding age, females who participated in the study are significantly older than males however, when it comes to BMI, males show a significant higher BMI than females (Table 1).

Additionally, preliminary analysis regarding the study’s variables means and standard deviation (Table 1) confirmed its consistency with past research in community samples (Cunha et al., 2013; Coimbra et al., 2023; Ferreira & Trindade, 2015; Ferreira et al., 2020; Senín-Calderón et al., 2017).

Correlation analyses

Pearson’s correlation coefficients calculated for all study variables are shown in Table 2. Results revealed that, in both groups, EISS presented a significant negative association with CAMM, a significant positive association with CFQ-BI and DCQ-P and a non-significant association with BMI. In turn, EISS showed a significant negative association with age in females, but a non-significant association in males.

In both groups, CAMM demonstrated a significant negative association with CFQ-BI and DCQ-P and a non-significant association with BMI. On the other hand, CAMM presented a significant positive association with age in females, but a non-significant association with the same variable in males. In addition, CFQ-BI was significantly and positively associated with DCQ-P for both males and females, showing, in contrast, significant associations with age and BMI in females, but revealing non-significant associations with the same variables in males.

DCQ-P demonstrated a significant negative association with age in females, but a non-significant negative association with age in males. It also demonstrated non-significant associations with BMI in both groups. Lastly, BMI was significantly and positively associated with age in both groups.

Path analyses

A path analysis was performed to examine the link between the experience of shame (EISS) and body dysmorphia-related symptomatology (DCQ-P), as well as the mediating effects of mindfulness (CAMM) and body image-related cognitive fusion (CFQ-BI) on this association, while controlling for the effects of age and BMI.

The hypothesized model was first calculated through a fully saturated model (i.e., zero degrees of freedom), consisting of 27 parameters. However, results indicated two non-significant paths: the path between BMI and CAMM ( = − 0.040; = 0.090; Z = − 0.446; p = .656) and the path between BMI and DCQ-P ( = − 0.073; = 0.050; Z = -1.447; p = .148). These paths were eliminated and the model gradually readjusted.

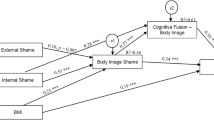

The recalculated model presented an adequate fit as indicated by the goodness-of-fit indices (= 2.286, p = .319; TLI = 0.996; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = 0.021, p = .567; 95% CI [0.000, 0.114]). This model accounted for 56% of the variance of DCQ-P, of 35% of the variance of CAMM, and 41% of the variance of CFQ-BI (Fig. 1).

The analysis of the direct effects demonstrated that EISS presented significant direct effects of − 0.56 on CAMM (= -5.263; = 0.432; Z = -12.192; p < .001), of 0.37 on CFQ-BI (= 6.948; = 1.002; Z = 6.932; p < .001), and of 0.13 on DCQ-P (= 0.844; = 0.309; Z = 2.728; p = .006). Additionally, CAMM presented a negative direct effect of − 0.28 on CFQ-BI ( = − 0.558; = 0.106; Z = -5.252; p < .001), which in turn presented a positive direct effect of 0.56 on DCQ-P (= 0.185; = 0.016; Z = 11.814; p < .001). Finally, CAMM also presented a negative direct effect of − 0.12 on DCQ-P ( = − 0.080; = 0.032; Z = -2.524; p = .012).

Regarding indirect effects, it was revealed that EISS presented an indirect effect of 0.16 on CFQ-BI, which was mediated by CAMM (95% CI [0.096, 0.220]; p < .001). Moreover, EISS presented a combined indirect effect of 0.36 (95% CI [0.273, 0.452]; p < .001) on DCQ-P, through mediation of CAMM and CFQ-BI. Finally, CAMM presented a negative indirect effect of − 0.15 (95% CI [-0.219, − 0.094]; p < .001) on DCQ-P, which was mediated by CFQ-BI.

Lastly, a multigroup analysis was performed to verify whether the paths coefficients of the final model are equal or invariant between the two groups (male and female). The results suggested that the model was invariant between male and female participants (χ2(4) = 10.964; p = .733).

Discussion

Several studies have demonstrated an association between shame and body dysmorphic symptomatology (e.g., Veale & Gilbert, 2014; Weingarden et al., 2018). However, the processes involved in this relationship have not been previously explored. Thus, the current study aimed to investigate the relationship between shame and body dysmorphia-related symptomatology and whether this association is influenced by mindfulness and body image-related cognitive fusion, while controlling for the effects of age and BMI. Moreover, this study aimed to explore biological sex differences regarding the studied variables and the relationships between them.

Concerning biological sex differences, the results revealed that, when compared to males, females presented higher levels of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology. Previous findings on this topic were conflicting (such as Bjornsson et al., 2010; Koran et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2006). Regarding shame, the results of the present study are contrary to those of previous ones (Else-Quest et al., 2012; Roberts & Goldenberg, 2007) since males and females did not present significant differences. Similarly, results did not reveal significant differences between males and females regarding mindfulness. Data concerning biological sex differences in mindfulness has been rather inconsistent: while Thirumaran and colleagues (2020) concluded that females present higher levels of mindfulness when compared to males, Webb and colleagues (2021) suggested that males present higher levels of mindfulness when compared to females. Additionally, Alispahic and Hasanbegovic-Anic (2017) hypothesized that the differences between males and females regarding levels of mindfulness might be influenced by the specific facet(s) being measured. This apparent inconsistency may also be due to the existing difficulties associated with an accurate assessment of mindfulness (Bergomi et al., 2013; Greco et al., 2011). Finally, results indicated that females had significant higher levels of body image-related cognitive fusion, when compared to males. Overall, these findings add to current literature, which seems to be limited regarding the inclusion of male participants and in the exploration of biological sex differences. Given the inconsistency of these findings and previous research, it seems that future studies should explore biological sex differences regarding the mentioned variables.

Correlation results are in line with previous research with non-clinical samples (Clerkin et al., 2014; Lavell et al., 2018; Roberts, 2019; Veale, 2004; Weingarden et al., 2018) by demonstrating that, in both groups, body dysmorphia-related symptomatology is negatively associated with mindfulness, as well as positively associated with the experience of shame. Furthermore, the results add to the literature by revealing a strong and positive association between body dysmorphia-related symptomatology and body image-related cognitive fusion. Additionally, mindfulness has also shown to be negatively associated with the experience of shame and with body image-related cognitive fusion, which goes in line with previous literature (Sedighimornani et al., 2019; Trindade & Ferreira, 2014; Woods & Proeve, 2014). Also consistent with previous research (Duarte et al., 2017), the results showed a positive association between shame and body image-related cognitive fusion.

To clarify the referred associations, a path analysis was conducted to understand whether the relationship between shame and body dysmorphia-related symptomatology is mediated by mindfulness and body image-related cognitive fusion, while controlling for age and BMI. The tested path model presented an excellent fit to the data accounting for 56% of the variance of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology, 35% of the variance of mindfulness, and 41% of the variance of body image-related cognitive fusion.

Results indicated that the experience of shame has an impact on body dysmorphia-related symptomatology. Results also revealed that, when faced with the experience of shame, the inability to be mindful is linked to higher levels of body image-related cognitive fusion which, in turn, is associated with higher severity of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology. These findings support our initial hypothesis by demonstrating that the impact the experience of shame has on the severity of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology partially depends on one’s capacity of being in the present moment in a non-judgmentally manner and on the level of entanglement with one’s thoughts, emotions, memories, and sensations regarding body image.

The multi-group analysis’ results revealed that the model is invariant across male and female. The findings suggest that, even though males and females revealed significant differences regarding body dysmorphia-related symptomatology, the relationship between the studied variables and body dysmorphia-related symptomatology is similar in both groups.

Even though this is a growing area of interest, this is the first study to assess the relationship between shame and body dysmorphic symptomatology through mindfulness and body image-related cognitive fusion. We believe these findings contribute to a better understanding of the role of the underlying emotional regulation processes in the study of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology. However, they should not be interpreted without considering some limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design used in this study impairs the possibility of drawing conclusions regarding causality between the variables. Secondly, the exclusive use of self-report measures through an online survey may increase bias, including recall bias, desirability bias and sample bias towards individuals who have easy access to social media. Thirdly, this study was conducted taking into account two groups, male and female, with considerably different sample sizes (female’s n = 244; male’s n = 83). Indeed, this is an expected limitation of the present study, since it is normal for female participants to have more interest in research projects regarding body image and related difficulties, such as body dysmorphia symptomatology. Further research should replicate this study using a longitudinal design as well as including different assessment methods (e.g., interviews) and a more homogeneous sample size. Additionally, we believe that further research would also benefit from studies that consider gender identity and the impact of body dysmorphia-related symptomatology.

Despite limitations, we believe our findings may have important research and clinical implications, essential for the advances in the study of body dysmorphic symptomatology. In fact, results emphasize the positive and powerful role that mindfulness can have in individuals presenting body dysmorphia-related symptoms. These results are in line with existing literature that considers mindfulness-based interventions useful for improving BDD symptoms, emotion dysregulation and executive functioning in patients with BDD (Gu & Zhu, 2023). Specifically, when faced with the experience of shame, enhancing mindfulness skills, and promoting cognitive defusion (i.e., promoting the ability to observe one’s thoughts as transient and subjective products of the mind, which do not need to be believed or responded to), seems to be essential for the development of intervention and prevention methods in the context of body dysmorphia. Thus, mindfulness emerges as a powerful tool, since it presents itself as the opposite notion of being entangled with one’s thoughts, by promoting acceptance, cognitive defusion, and contact with the present moment (Hayes et al., 2006).

Data Availability

Data from the present study is not available since it is still being used as part of a wider research on Body Dysmorphia. However, data can be available upon request to the authors.

Notes

For statistical purposes, we were, unfortunately, unable to include in this study individuals who chose not to disclose their biological sex/ did not identify as male or female.

References

Alispahić, S., & Hasanbegović-Anić, E. (2017). Mindfulness: Age and gender differences on a Bosnian sample. Psychological Thought, 10(1), 155–166.

Almeida, V., Leite, Â., Constante, D., Correia, R., Almeida, I. F., Teixeira, M., Vidal, D. G., et al. (2020). The Mediator Role of Body Image-Related Cognitive Fusion in the relationship between Disease Severity Perception, Acceptance and Psoriasis Disability. Behavioral Sciences, 10(9), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10090142

Altamura, C., Paluello, M. M., Mundo, E., Medda, S., & Mannu, P. (2001). Clinical and subclinical body dysmorphic disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 251(3), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004060170042

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2013). Amos (Version 22.0) [Computer program]. SPSS.

Bergomi, C., Tschacher, W., & Kupper, Z. (2013). The assessment of mindfulness with self-report measures: Existing scales and open issues. Mindfulness, 4, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0110-9

Bjornsson, A. S., Didie, E. R., & Phillips, K. A. (2010). Body dysmorphic disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.2/abjornsson

Bjornsson, A. S., Didie, E. R., Grant, J. E., Menard, W., Stalker, E., & Phillips, K. A. (2013). Age at onset and clinical correlates in body dysmorphic disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(7), 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.03.019

Brohede, S., Wingren, G., Wijma, B., & Wijma, K. (2015). Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder among Swedish women: A population-based study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.12.014

Clerkin, E. M., Teachman, B. A., Smith, A. R., & Buhlmann, U. (2014). Specificity of implicit-shame associations: Comparison across body dysmorphic, Obsessive-Compulsive, and social anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(5), 560–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614524944

Cohen, J. (1998). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Coimbra, M., Melo, D., Moura-Ramos, M., Ganho-Ávila, A., & Ferreira, C. (2023). Investing in the study of body dysmorphia: Validation of the first Portuguese measure, relationship with other psychopathology measures and gender. Manuscript in preparation.

Cunha, M., Galhardo, A., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2013). Child and adolescent mindfulness measure (CAMM): Estudo das características psicométricas da versão portuguesa. Psicologia: Reflexão E Crítica, 26(3), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722013000300005

Didie, E. R., Tortolani, C. C., Pope, C. G., Menard, W., Fay, C., & Phillips, K. A. (2006). Childhood abuse and neglect in body dysmorphic disorder. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(10), 1105–1115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.007

Didie, E. R., Loerke, E. H., Howes, S. E., & Phillips, K. A. (2012). Severity of interpersonal problems in individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2012.26.3.345

Duarte, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Ferreira, C. (2017). Ashamed and fused with body image and eating: Binge eating as an avoidance strategy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1996

Else-Quest, N. M., Higgins, A., Allison, C., & Morton, L. C. (2012). Gender differences in self-conscious emotional experience: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 947–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027930

Ferreira, C., & Trindade, I. A. (2015). Body image-related cognitive fusion as a main mediational process between body-related experiences and women’s quality of life. Eating and Weight Disorders, 20(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-014-0155-y

Ferreira, C., Trindade, I. A., Duarte, C., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2015). Getting entangled with body image: Development and validation of a new measure. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 88(3), 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12047

Ferreira, C., Moura-Ramos, M., Matos, M., & Galhardo, A. (2020). A new measure to assess external and internal shame: Development, factor structure and psychometric properties of the external and internal shame scale. Current Psychology, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00709-0

Forman, E. M., & Butryn, M. L. (2015). A new look at the science of weight control: How acceptance and commitment strategies can address the challenge of self-regulation. Appetite, 84, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.004

Gatward, N. (2007). Anorexia Nervosa: An evolutionary puzzle. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 15(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.718

Gilbert, P. (1998). What is shame? Some core issues and controversies. In P. Gilbert, & B. Andrews (Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behaviour, psychopathology and culture (pp. 3–36). Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P. (2007). The evolution of shame as a marker for relationship security. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 283–309). Guilford Press.

Gilbert, P., & Andrews, B. (Eds.). (1998). Shame: Interpersonal behaviour, psychopathology and culture. Oxford University Press.

Gillanders, D. T., Bolderston, H., Bond, F. W., Dempster, M., Flaxman, P. E., Campbell, L., Kerr, S., Tansey, L., Noel, P., Ferenbach, C., Masley, S., Roach, L., Lloyd, J., May, L., Clarke, S., & Remington, B. (2014). The development and initial validation of the cognitive fusion questionnaire. Behavior Therapy, 45(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.09.001

Grant, J. E., Kim, S. W., & Eckert, E. D. (2002). Body dysmorphic disorder in patients with Anorexia Nervosa: Prevalence, clinical features, and delusionality of body image. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10091

Greco, L. A., Baer, R. A., & Smith, G. T. (2011). Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the child and adolescent mindfulness measure (CAMM). Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022819

Gu, Y. Q., & Zhu, Y. (2023). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: Impact on core symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and executive functioning. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2023.101869

Guendelman, S., Medeiros, S., & Rampes, H. (2017). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: Insights from neurobiological, psychological, and clinical studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00220

Haider, A., Wei, Z., Parveen, S., & Mehmood, A. (2023). The association between comorbid body dysmorphic disorder and depression: Moderation effect of age and mediation effect of body mass index and body image among Pakistani students. Middle East Curr Psychiatry, 30, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00283-8

Harris, R. (2009). ACT made simple: An easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Hayes, S. C., & Wilson, K. (2006). Mindfulness: Method and process. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg018

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Jassi, A., & Krebs, G. (2021). Body dysmorphic disorder: Reflections on the last 25 years. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 26(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104520984818

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2015). Mindfulness Mindfulness, 6, 1481–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0456-x

Kline, R. (2011). Principals and practice of structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Koran, L. M., Abujaoude, E., Large, M. D., & Serpe, R. T. (2008). The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in the United States adult population. CNS Spectrums, 13(4), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1092852900016436

Lavell, C. H., Webb, H. J., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Farrell, L. J. (2018). A prospective study of adolescents’ body dysmorphic symptoms: Peer victimization and the direct and protective roles of emotion regulation and mindfulness. Body Image, 24, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.11.006

Malcolm, A., Pikoos, T., Castle, D. J., Labuschagne, I., & Rossell, S. L. (2021). Identity and shame in body dysmorphic disorder as compared to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2021.100686

Matos, M., Coimbra, C., & Ferreira, C. (2023). When body dysmorphia symptomatology meets disordered eating: The role of shame and self-criticism. Appetite, 186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.106552

Morselli, E. (1891). Sulla dismorfofobia e sulla tafefobia. Bollettino Della R Accademia Di Genova, 6, 110–119.

Oosthuizen, P., Lambert, T., & Castle, D. J. (1998). Dysmorphic concern: Prevalence and associations with clinical variables. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 32(1), 129–132. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048679809062719

Phillips, K. A. (2007). Suicidality in body dysmorphic disorder. Primary Psychiatry, 14(12), 58–66.

Phillips, K. A., Menard, W., Fay, C., & Weisberg, R. (2005). Demographic characteristics, phenomenology, comorbidity, and family history in 200 individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics, 46(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.46.4.317

Phillips, K. A., Menard, W., & Fay, C. (2006). Gender similarities and differences in 200 individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47(2), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.07.002

Poínhos, R., Franchini, B., Afonso, C., Correia, F., Teixeira, V. H., Moreira, P., Durão, C., Pinho, O., Silva, D., Reis, L., Veríssimo, J. P., T., & de Almeida, M. D. V. (2009). Alimentação E estilos de vida da população portuguesa: Metodologia E resultados preliminares. Alimentação Humana, 15(3), 43–60.

Rief, W., Buhlmann, U., Wilhelm, S., Borkenhagen, A., & Brähler, E. (2006). The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: A population-based survey. Psychological Medicine, 36(6), 877–885. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706007264

Roberts, C. L. (2019). Body Dysmorphic Disorder in adolescents: A new multidimensional measure and associations with social risk, mindfulness, and self-compassion. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Griffith University, Queensland, Australia. https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/551

Roberts, T., & Goldenberg (2007). Wrestling with nature: An existential perspective on the body and gender in self-conscious emotions. In Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Tangney J. P. (Eds.) (2007). The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 389–406). Guilford.

Ruffolo, J. S., Phillips, K. A., Menard, W., Fay, C., & Weisberg, R. B. (2006). Comorbidity of body dysmorphic disorder and eating disorders: Severity of psychopathology and body image disturbance. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20219

Schulte, J., Schulz, C., Wilhelm, S., & Buhlmann, U. (2020). Treatment utilization and treatment barriers in individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Bmc Psychiatry, 20(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02489-0

Sedighimornani, N., Rimes, K. A., & Verplanken, B. (2019). Exploring the relationships between mindfulness, self-compassion, and shame. SAGE Open, 9(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019866294

Senín-Calderón, C., Valdés-Díaz, M., Benítez-Hernández, M. M., Núñez-Gaitán, M. C., Perona-Garcelán, S., Martínez-Cervantes, R., & Rodríguez-Testal, J. F. (2017). Validation of Spanish Language Evaluation Instruments for Body Dysmorphic Disorder and the Dysmorphic Concern Construct. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01107

Thirumaran, M., Vijayaraman, M., Irfan, M., Moinuddin, S. K., & Shafaque, N. (2020). Influence of age and gender on mindfulness-cognitive science. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development, 11(3), 882–886.

Trindade, I. A., & Ferreira, C. (2014). The impact of body image-related cognitive fusion on eating psychopathology. Eating Behaviors, 15(1), 72–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.10.014

Veale, D. (2004). Advances in a cognitive behavioural model of body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 1(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00009-3

Veale, D., & Gilbert, P. (2014). Body dysmorphic disorder: The functional and evolutionary context in phenomenology and a compassionate mind. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 3(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2013.11.005

Veale, D., Gledhill, L. J., Christodoulou, P., & Hodsoll, J. (2016). Body dysmorphic disorder in different settings: A systematic review and estimated weighted prevalence. Body Image, 18, 168–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.07.003

Webb, L., Sibinga, E., Musci, R., Clary, L. K., & Mendelson, T. (2021). Confirming profiles of comorbid psychological symptoms in urban youth: Exploring gender differences and trait mindfulness. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(11), 2249–2261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01509-w

Weingarden, H., & Renshaw, K. D. (2015). Shame in the obsessive compulsive related disorders: A conceptual review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 171, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.010

Weingarden, H., Curley, E. E., Renshaw, K. D., & Wilhelm, S. (2017). Patient-identified events implicated in the development of body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 21, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.02.003

Weingarden, H., Shaw, A. M., Phillips, K. A., & Wilhelm, S. (2018). Shame and defectiveness beliefs in treatment seeking patients with body dysmorphic disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(6), 417–422. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000808

Woods, H., & Proeve, M. (2014). Relationships of mindfulness, self-compassion, and meditation experience with shame-proneness. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 28(1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.28.1.20

World Health Organization (1995). Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. Reports of a 5 WHO expert committee. World Health Organization Technical Report Series, 854, 1–452.

Funding

Not applicable.

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors Cláudia Ferreira and Maria Coimbra designed the study and wrote the protocol. Authors Maria Francisca Oliveira and Maria Coimbra conducted literature research, the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. Author Cláudia Ferreira supervised and contributed to these tasks and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra and were performed in line with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveira, M.F., Coimbra, M. & Ferreira, C. How does the experience of shame impact body dysmorphic symptomatology? Exploring the role of mindfulness and body image-related cognitive fusion. Curr Psychol 43, 13454–13464 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05385-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05385-4