Abstract

Although cross-sectional and daily diary studies have noted associations among trait mindfulness and positive and negative affect, lacking are studies that longitudinally examine these relationships over a period of months. We tested whether trait mindfulness (assessed with the Five Facet Mindfulness Measure) predicted an increase in positive affect and a decrease in negative affect across 3 months. A sample of 319 community adults completed self-report measures of mindfulness, positive affect, and negative affect at three times of measurement separated by three months each. As hypothesised, overall mindfulness, tested with a random intercepts cross-lag path model, predicted over three months a decrease in negative affect, but, contrary to predictions, did not predict an increase in positive affect. In the reverse direction, within-subject negative affect predicted decreases of overall within-subject mindfulness, which suggests that this relationship may be reciprocal over time. When examined at the facet level of mindfulness, all five within-subject facets of the FFMQ predicted reductions in within-subject negative affect over time. In return, within-subject negative affect predicted reductions in three within-subject mindfulness facets: non-reacting, acting with awareness, and describing. On balance, the results of this study suggest that trait mindfulness, as assessed with the FFMQ, was much more successful in predicting diminished negative affect than in predicting a boost in positive affect. Further, the presence of negative affect seems to exert an inhibiting influence over time on the implementation of several mindfulness facets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Both positive and negative affect play essential roles in the human condition. The hedonic tone of our mood impacts our day-to-day experience, our enjoyment of life, and our abilities to effectively engage with life. Positive affect is a state of concentration in which one is alert, energetic, optimistic, and engaged (Watson et al., 1988), while negative affect includes subjective feelings of worry, tension, nervousness, and psychological distress (Watson & Clark, 1984). One emotion regulation strategy, namely mindfulness, has been proposed to be effective in altering the experienced valence of daily moods. Mindfulness is defined as the practice of focusing on the present moment in a non-evaluative fashion (Kabat-Zinn, 1990), and it has been shown to be significantly and positively associated with positive affect, life satisfaction, and general well-being (Seear & Vella-Brodrick, 2012; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Additionally, mindfulness has been negatively linked with rumination, depressive symptoms, and a range of negative mood states (e.g., Jury & Jose, 2019; Raes & Williams, 2010). Mindfulness is thought to foster increases in positive affect and decreases in negative affect by intentionally shifting attention to the present and promoting a non-judgmental stance toward one’s feelings (e.g., Blanke et al., 2018).

Mindfulness has been viewed as a skill that can be learned and developed through instruction and practice (Bishop et al., 2004), as evidenced by the great number of programs and interventions that have been developed to help people live more mindfully. This view primarily conceptualizes mindfulness as a state, such that a person is trained to achieve a mindful state with practice and focused attention. However, mindfulness can also be conceptualized as a naturally occurring disposition or trait, defined as the stable ability of an individual to intentionally and flexibly attend with receptive awareness to the experiences of the present moment (Brown & Ryan, 2003). The present study examines relationships between trait mindfulness with positive and negative affect over time in order to determine how naturally occurring mindfulness abilities wax and wane temporally with naturally occurring positive and negative affective states.

Although a number of studies have documented that mindfulness positively predicts positive mood states and negatively predicts negative mood states over hour-to-hour or day-to-day periods of time in daily diary studies (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Keng & Tong, 2016; Weinstein et al., 2009), the literature lacks longitudinal studies that examine the ability of trait mindfulness to predict levels of positive and negative affect over longer periods of time. The present study was designed to determine whether trait mindfulness would exhibit the same predictive relationships found over hours and days to periods of three months. The answer to this question is pragmatically important because whether these temporal relationships last longer than hours or days has implications for the design and assessment of clinical treatment and interventions.

Relationships between trait mindfulness and positive and negative affect

Trait mindfulness has been associated with affect in both clinical and non-clinical adult populations (Erisman & Roemer, 2010, 2012; Quoidbach et al., 2010). Jimenez et al. (2010) examined the relationship between trait mindfulness and affect in 514 students in a cross-sectional study, and they found that higher levels of trait mindfulness were associated with higher levels of positive emotions, although it was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms. In another cross-sectional study (N = 100 students), Mandal et al. (2012) found that trait mindfulness was positively correlated with positive affect and negatively correlated with negative affect. In a meta-analysis on personality, affect, and mindfulness, Giluk (2009) similarly found that mindfulness was positively (and concurrently) associated with positive affect and negatively associated with negative affect.

Some evidence exists of temporal effects among these constructs: trait mindfulness has been shown to predict increases in positive affect and decreases in negative affect (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Keng & Tong, 2016; Weinstein et al., 2009). It is notable, however, that the studies that have investigated these temporal associations have all exclusively used ecological momentary assessment (EMA), also known as the experience sampling method (ESM) or the daily diary method. The results of these studies are limited to an understanding of hourly or daily changes in affect rather than changes in affect over longer periods of time such as weeks or months.

The daily diary method has also been used in studies measuring the influence of mindfulness interventions. Snippe et al. (2015) assessed mindfulness and positive and negative affect on a daily basis in 83 general population individuals who participated in a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program. Day-to-day changes in mindfulness predicted subsequent day-to-day changes in both positive and negative affect, however the reverse was not found. These findings suggest that efforts to increase mindfulness on a daily basis can be beneficial for improving daily psychological well-being by boosting positive affect and reducing negative affect. In a similar study, Garland, Geschwind et al. (2015) examined positive emotion-cognition interactions among 130 individuals in partial remission from depression who were randomly assigned to treatment with mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) or to a waitlist control condition. The researchers found that the treatment condition was associated with significant increases in positive affect, suggesting that daily positive affect and cognition promote each other in an upward spiral supported by mindfulness training.

Other studies have examined the associations between mindfulness and daily affect in the absence of any intervention. Blanke et al. (2019) investigated associations between daily mindfulness, emotion regulation, and positive and negative affect in everyday life using data from two ESM studies (Ns = 70 and 179). Among individuals who reported a more mindful state, rumination was less strongly associated with increases in negative affect and was less strongly associated with decreases in positive affect. Thus, mindfulness seemed to inhibit maladaptive emotion regulation and its suppressing impact on positive affect. In another ESM study, Keng and Tong (2016) investigated the association between trait mindfulness and affect dynamics, i.e., patterns of daily affect fluctuations. Using the daily diary method with 390 students, the findings revealed that trait mindfulness independently promoted adaptive patterns of affective experiences in daily life by inhibiting maladaptive coping.

Although these ESM studies have documented that mindfulness is fairly reliable in predicting changes in positive and negative affect over short periods of time, questions remain regarding whether mindfulness exerts more long-lasting effects on positive and negative affect. The current study was designed to answer this question outside of the ESM context with trait mindfulness.

A related question—whether positive and negative affect exert an impact upon the levels of mindfulness—is important to consider within this frame, but little work has examined valenced affect as precursors to mindfulness. To date, only one study (i.e., Snippe et al., 2015) has investigated how positive and negative affect predict changes in mindfulness, and these authors found no reliable relationship in this direction. From a theoretical point-of-view, however, Fredrickson’s (1998, 2004) broaden-and-build theory posits that the experience of positive affect should boost effective cognition, which over time should build a wide range of personal resources, including mindfulness (Fredrickson et al., 2008). Thus, this theory would posit that positive affect would be a predictor of increased mindfulness over time. Similarly, negative emotions are thought to create a downward spiral of self-perpetuating and damaging negativity and negative cognitions (Garland et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2021; Wu & Chang, 2019), which are likely to predict a decrease in mindfulness over time. Fredrickson’s (1998) observed that problems and negative emotions tend to narrow one’s cognitive and emotional perspectives, often leading to the use of avoidance and denial. Mindfulness, in contrast, musters non-judging, non-reacting, and acting with awareness strategies in responses to difficulties which, in Fredrickson et al.’s view (2008), leads to an accepting and open approach. Thus, positive affect may enhance enactment of mindfulness, whereas negative affect may suppress employment of mindfulness. At present, the literature shows that the findings of a single study by Snippe et al. (2015) are inconsistent with these theoretical expectations, so more research is needed to test these important and provocative theoretical predictions.

Goals of the present study

While the daily diary studies cited above provide important insights into the associations between mindfulness and positive and negative affect at the daily level, the effect of trait mindfulness on positive and negative affect over longer periods of time remains unknown. Although this published evidence of day-to-day linkages between state mindfulness and state affect is heartening, none of these studies have demonstrated the ability of trait mindfulness to predict improved affect over weeks or months. This gap in our knowledge needs to be addressed because the answer will have important implications for interventions based on the assumption that teaching mindfulness can have long-lasting positive effects (e.g., Harp et al., 2022). Thus, the present study will address an important lacuna in our understanding of the temporal relationships between mindfulness and affect.

In our three time-point longitudinal study, with assessments separated by three months each, we first sought to investigate whether trait mindfulness would manifest a predictive influence on positive and negative affect over three months. And second, we desired to know whether the variables would exhibit relationships in the reverse direction, namely would positive and negative affect predict changes in trait mindfulness over time?

Based on the existing mindfulness literature (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Keng & Tong, 2016; Weinstein et al., 2009) and Fredrickson’s (1998) broaden-and-build theory, it was hypothesized that mindfulness would predict an increase in positive affect over three months (Hypothesis 1), and positive affect, in reverse, would predict an increase in mindfulness (Hypothesis 2). We also expected to see that mindfulness would predict a decrease in negative affect over time (Hypothesis 3), and negative affect, in reverse, would predict a decrease in mindfulness (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Participants

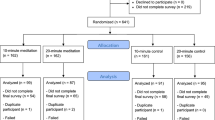

Individuals 16 years and over living anywhere in New Zealand were invited to participate in three data collection waves separated by three months each for the New Zealand Happiness Study. A sample of 552 individuals provided data for the first of three waves, but significant attrition was observed in waves 2 and 3. To minimise imputation across different waves, we included in our final sample a group of 319 participants who participated in all three waves of data collection, ranging in age from 16 to 80 years, with a mean age of 38.8 years (SD = 16.41). The sample included 219 females and 100 males, so it is acknowledged that the gender ratio was significantly skewed. The large majority, 78.3%, of the participants in the sample identified as Pakeha/NZ European, 4.3% identified as Maori, 0.9% as Pacific Nations, 2.4% as Asian, and 7.4% specified their ethnicity as “other” (and 6.7% of participants did not specify their ethnicity).

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained prior to data collection in 2011 from the authors’ home institution. The longitudinal subject variable design of the current study involved the completion of an online survey at three time points approximately three months apart. Byrne and van de Vijver (2010) have stated that a three-month time frame is appropriate when observing the temporal relationships among moderately stable variables over time.

Recruitment flyers were sent to community groups, retirement villages, workplaces, and recreation centres across New Zealand. An invitation was also put on www.facebook.com and placed in two large city newspapers. Following recruitment, participants were assigned a unique identification number, and the individual completions of the survey were linked with this number. The list of names-to-numbers was deleted at the conclusion of the study so the data became anonymous.

The survey included a large battery of measures relating to the emotional functioning of the individual as well as demographic questions. The survey took approximately 40–50 min to complete, and participants were reminded that their participation was both voluntary and confidential prior to beginning. Participants indicated consent by participating. Participants were contacted through e-mail, post, or telephone to advise them of the next survey completion date. Those individuals who completed the survey at all three time points received a $20 gift voucher as a token of appreciation.

Measures

The two measures that were used in the current study are: the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006) and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Short Form (PANAS-SF; Watson et al., 1988).

The Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

The FFMQ (Baer et al., 2006) was used to measure self-report mindfulness in the current study. The FFMQ is a multidimensional measure of mindfulness and is currently the most widely used measure of mindfulness. The FFMQ is a 39-item scale which is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never or very rarely to 5 = very often or always). Participants were asked to choose the option that best describes what is true for them. Items in the FFMQ tap onto one of five facets of mindfulness, namely observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reacting to inner experience. The FFMQ has demonstrated good psychometric properties in student samples and community samples (Baer et al., 2006; Christopher et al., 2012). The FFMQ exhibited good internal reliability at all time points in the present study (see Table 1).

Positive And Negative Affect Schedule-Short form

The short form version of the PANAS (Watson et al., 1988) was used to assess self-report levels of both positive and negative affect. This scale consisted of 20 items, and responses to the statement “Indicate the extent you have felt this way over the past week” were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely). Ten items captured positive affect (e.g., interested, proud), and ten items tapped negative affect (e.g., upset, hostile). The PANAS has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity in a range of different samples (Crawford & Henry, 2004). In this sample, high internal reliability for the two subscales of this measure was found at each time point (see Table 1).

Data analyses

The primary goal of the current study was to determine whether: (1) levels of within-subject mindfulness would positively predict within-subject positive affect and negatively predict within-subject negative affect over time, and (2) whether, in turn, within-subject positive and/or negative affect would predict within-subject mindful states over time. First, Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM; Amos Development Corporation, 2020) in AMOS were used to confirm that both measures would demonstrate temporal invariance, i.e., confirm the assumption that these measures functioned similarly over time. And second, two random intercepts cross-lag path models (RI-CLPM) were created through latent variable path modelling to test the four temporal hypotheses. Hamaker et al. (2015) recommend the use of RI-CLPM over traditional longitudinal cross-lag panel models because this method partitions between-person and within-person variance, allowing for temporal relationships to be based on within-person change over time uncontaminated by between-person stabilities (see also Anderson, 2021). We implemented the suggested specifications of Mulder and Hamaker (2021) for our RI-CLPM models (their Fig. 1 on p. 639), and the models were estimated in the SEM program IBM Amos Ver. 29 (2022).

Results

Treatment of missing data

Missing values analysis found only a small amount of idiosyncratic missingness (3.6% of data was missing, ranging from 0 to 5.2% missingness at the variable level). Little’s MCAR test yielded non-significance, p = .78, indicating that the missing data were missing completely at random. The missing values in the dataset were then imputed using the estimation maximization (EM) procedure in order to best estimate the missing data points and thus retain the full sample size.

Following the guidelines of Trochim and Donnolly (2006) and Field (2009), values for skew and kurtosis between − 2 and + 2 are considered to be acceptable. Analyses revealed that our variables of mindfulness and positive affect fell in the acceptable range, but our variable of negative affect was excessively kurtotic (values > 3.0). This result is common among studies using a negative psychological construct and is sometimes dealt with by transforming the problematic data (e.g., Hereen & Philippot, 2011). However, transforming such variables creates an artificial and arbitrary metric, making it difficult to interpret results, particularly in the context of other variables which are not transformed. Taking this fact into consideration, logarithmic transformations were performed on the negative affect variable at all time points. This transformation brought skew and kurtosis to acceptable levels, however, reanalyses yielded the same results (i.e., significance or non-significance of all results remained the same) as with the untransformed data. Log-transformed NA correlated 0.98, 0.99, and 0.98 with the untransformed NA variables at the three respective time points. Thus, we have decided to report results from the untransformed data because they conform to a metric which is interpretable.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for overall mindfulness and positive and negative affect scores at all three time points are presented in Table 1. All variables were consistently correlated in the expected directions within and over the three time points, namely overall mindfulness was positively correlated with positive affect, and both of these variables were negatively correlated with negative affect. Mean scores for each variable fell within ranges that would be expected for a community sample, i.e., low for negative affect but slightly higher than the mid-point of the scale for both positive affect and mindfulness. All scales yielded excellent internal reliabilities.

Temporal invariance of the scales

We next tested whether the PANAS and FFMQ scales exhibited acceptable temporal invariance over the three times of measurement. A previous report by one of the current authors (Jury & Jose, 2019) established that the FFMQ exhibited temporal invariance in the same dataset as examined here. However, we needed to establish temporal invariance for the PANAS for this dataset. Byrne and van de Vijver (2010) recommend the use of temporal invariance SEM tests in which the three levels of configural, metric, and scalar invariance are tested in turn. One rejects the hypothesis of temporal invariance if two of the following three criteria are observed: Δχ2 significant at p < .05; ΔCFI > 0.01; and ΔRMSEA > 0.015 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000) between the three increasingly constrained models. Since the PANAS is a scale that includes the two related subfactors of PA and NA, CFAs were run on a model where PA and NA were included simultaneously with a covariance specified between the two latent constructs. CFAs were run across all three time-spans (e.g., between T1 and T2, between T1 and T3, and between T2 and T3).

Temporal invariance was identified for the PANAS at each time comparison (see Table 2), using ΔCFI > 0.01; and ΔRMSEA > 0.015 as the relevant criteria. The scale exhibited exemplary temporal invariance for both indices for all three levels of temporal invariance. These results indicated that the PANAS measured positive and negative affect consistently across the three time points.

Temporal relationships of mindfulness and valenced affect: Did mindfulness predict affect or did affect predict mindfulness?

The predictions suggested that within-subject mindfulness would predict increases in within-subject positive affect and decreases in within-subject negative affect over time, and that, in return, valenced within-subject affect would have an impact upon within-subject mindfulness over time. In order to test these hypotheses, we created two random intercepts cross-lag path models (see Figs. 1 and 2) based on recommendations by Hamaker et al. (2015) and Mulder and Hamaker (2021). We constructed one model to test relationships between mindfulness and PA and a second model to test relationships between mindfulness and NA. In order to obtain results unconfounded with key demographic variables, we also covaried age and gender out of the model. We had no reason to expect that strengths of identical cross-lags would differ between T1 to T2 and T2 to T3, and since the relevant chi-square tests yielded non-significant results (for the NA model, χ2ch(2) = 5.74, p = .06; for the PA model, χ2ch(2) = 4.46, p = .11, we set respective pairs of cross-lags to equality to simplify the models and interpretations. Model fitting estimations yielded good model fit indices for the NA model: χ2/df ratio = 2.42, SRMR = 0.04, NFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; and for the PA model: χ2/df ratio = 1.91, SRMR = 0.02, NFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99. As expected, estimations of the random intercepts yielded statistical significance: RI-FFMQ = 0.063, SE = 0.01, p < .001; RI-NA = 0.177, SE = 0.02, p < .001; and RI-PA = 0.265, SE = 0.03, p < .001. These values indicate the presence of considerable between-subject variability, and provide persuasive evidence that RI models should be estimated rather than the standard CLPM (Mulder & Hamaker, 2021) which confounds within- and between-subject variances.

Random intercepts cross-lag path model examining temporal relationships among overall mindfulness and positive affect

Note. Length of time between T1 and T2 (and between T2 and T3) was three months. N = 319. FFMQ = overall mindfulness; PA = positive affect; Betw = between-subjects variance; Within = within-subjects variance. The model depicted here does not include covariances between within-subject variables of PA and FFMQ within each time point for the sake of clarity. Numerical values are standardised regression coefficients. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; NS = nonsignificant.

Random intercepts cross-lag path model examining temporal relationships among overall mindfulness and negative affect

Note. Length of time between T1 and T2 (and between T2 and T3) was three months. N = 319. FFMQ = overall mindfulness; NA = negative affect; Betw = between-subjects variance; Within = within-subjects variance. The model depicted here does not include covariances between within-subject variables of NA and FFMQ within each time point for the sake of clarity. Numerical values are standardised regression coefficients. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; NS = nonsignificant.

Hypotheses 1 and 2: Mindfulness would predict increases in positive affect and positive affect would predict increases in mindfulness

Contrary to hypotheses, within-subject mindfulness did not significantly predict an increase in within-subject positive affect, β = 0.03, p = .68, and within-subject positive affect did not significantly predict an increase in positive affect, β = 0.03, p = .54 (see Fig. 1).

Hypotheses 3 and 4: Mindfulness would predict decreases in negative affect and negative affect would predict decreases in mindfulness

In contrast to the previous two hypotheses, we found support for Hypothesis 3, namely, within-subject mindfulness predicted decreases in within-subject negative affect, β = − 0.19, p = .002, and Hypothesis 4, namely, within-subject negative affect predicted decreases in within-subject mindfulness, β = − 0.11, p = .044 (see Fig. 2). Thus, it seems that within-subject mindfulness predicted changes in within-subject NA over time and was also predicted by prior within-subject NA, whereas no such relationships were found for PA.

Exploratory analyses: Did these relationships exist similarly for all five mindfulness facets?

We tested the uniformity of these results for the five mindfulness facets by running the same random intercepts cross-lag path model for each of the facets separately, and these exploratory results are presented in Table 3. We acknowledge that running a model with all five facets included simultaneously would be analytically better than separate runs, but our sample size was inadequate for a model that complex.

Table 3 reports the standardized regression coefficients (beta weights) for all relationships, and 10 out of 20 cells yielded significant results. Focusing on the FFMQ to NA relationship, we see that all five within-subject facets were negatively predictive of within-subject NA over time, and non-reacting (β = − 0.30) and acting with awareness (β = − 0.27) were the strongest predictors. In the reverse direction, within-subject NA predicted lower levels of within-subject non-reacting, acting with awareness, and describing. Within-subject observing and non-judging were not significantly compromised by the previous occurrence of within-subject NA. With regard to the FFMQ to PA relationship, two individual relationships were noted: within-subject acting with awareness significantly predicted increases in within-subject PA, and within-subject PA seemed to predict levels of the within-subject observing facet of mindfulness.

Results of these exploratory analyses suggest that all of the within-subject FFMQ facets were involved in the diminishment of within-subject NA over time, and most of the FFMQ facets were diminished by the earlier within-subject NA. In contrast, very few relationships were noted between within-subject FFMQ facets and within-subject PA, despite previous theory and empirical findings suggesting that mindfulness should foster greater PA.

Discussion

Mindfulness to affect

The present study provided evidence, using a random intercepts model, that within-subject mindfulness predicted a decrease in within-subject negative affect over time, but not an increase in within-subject positive affect. These findings diverge somewhat with what has been found in other studies that have examined these relationships using the experience sampling method (ESM) or the daily diary method (Blanke et al., 2018; Keng & Tong, 2016; Snippe et al., 2015). The findings of the present study indicate that the effect of within-subject mindfulness on within-subject negative affect persists for at least a period of three months. Interestingly, although ESM studies show that mindfulness boosts PA, our findings suggest that those relationships, based on within-subject variance, are not maintained over three months. These results suggest that trait mindfulness may more powerfully reduce negative affect than it increases positive affect. Consistent with that view, Glück and Maercker’s (2011) web-based mindfulness training program showed improvements for negative affect but not for positive affect (as measured by the PANAS). Although numerous concurrent datasets (e.g., McLaughlin et al., 2019) report high correlations of mindfulness with both positive and negative affect, the relationship between mindfulness and negative affect may be larger and more enduring than the one with positive affect over time. In sum, no previous longitudinal study has examined these relationships over a period of months or with a random intercepts model, so our findings make an important contribution to the literature that has not been identified before.

One relationship at the facet level suggested a pathway from within-subject mindfulness to increases in within-subject positive affect, namely acting with awareness positively and robustly predicted PA three months later. Other studies—concurrent, daily diary, and experimental—have supported this particular relationship (e.g., Brown & Ryan, 2003; Garland, Farb et al., 2015; Garland, Geschwind et al., 2015), but our longitudinal dataset analysed with the RI-CLPM approach suggests that the only FFMQ facet to predict positive affect is acting with awareness, a dynamic often construed to be the core feature of mindfulness (Bishop et al., 2004).

Affect to mindfulness

Another distinctive characteristic of our study was the examination of the reverse relationship: did within-subject positive and negative affect predict changes in within-subject mindfulness over three months? The results show that within-subject negative affect (but not positive affect) was found to predict diminishment of overall within-subject mindfulness over a three month period of time. This result contradicts the finding obtained from the only other study to date that has investigated this relationship, albeit with a standard CLPM. Snippe et al. (2015) found no association over time from valenced affect to mindfulness, but the present study found a significant (and interpretable) within-subject association between NA and subsequent overall mindfulness, and the exploratory analyses suggested that these reductions occurred in three separate mindfulness facets. In particular, within-subject NA predicted lower levels of the within-subject FFMQ facets of non-reacting, acting with awareness, and describing, which suggests that NA interfered with the ability of individuals to resist self-involvement with problems, being self-aware, and being capable of describing self-oriented cognitions and emotions. All mindfulness facets require psychological resources, i.e., the cognitive and emotional efforts of focusing awareness, being in the present, and avoiding attachment to negative emotions, but these three particular mindfulness facets may be more ‘fragile’ in the face of negative emotions or more resource-intensive than the non-judging and observing facets. Future work should investigate why some facets are more vulnerable to the destabilising effects of negative affect than others. In sum, one explanation for this lack of agreement with the Snippe et al. study may be that they investigated within-person changes in positive and negative affect during a mindfulness training program (MBSR), and such programs tend to assess state mindfulness, whereas the present study measured changes in a person’s trait mindfulness over time. In addition, the present study did not include any intervention, whereas the Snippe et al. study did so. And third, we employed a random intercepts approach to studying intraindividual change unconfounded with between-subject variance.

Although we did not find that PA predicted an increase in overall mindfulness, one facet was boosted by previous PA: namely, observing. Observing (or observation) involves “how we see, feel, and perceive the internal and external world around us and select the stimuli that require our attention and focus” (Chowdhury, 2019). This finding from our exploratory analyses provides support for our prediction that PA would build psychological resources consistent with Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory: it seems that positive emotions enhanced the ability to broaden the ways in which people apprehended the world around and within them. But it is acknowledged that no general pattern of PA to multiple mindfulness facets was obtained here; this finding will need to be replicated in order to boost our confidence in this isolated result.

Beyond this single relationship for PA, we did find solid support for a useful corollary to the broaden-and-build theory, namely that negative mood states seem to predict lessened subsequent mindfulness. What we call the ‘narrow-and-weaken’ dynamic (called ‘narrowed thought-action repertoires’ or the ‘narrow hypothesis’ by Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005) has been discussed previously (Garland et al., 2010), and it speaks to the deleterious effects of negative mood states. It was notable that all five FFMQ facets evidenced a diminishment following a period of high negative affect, and this result suggests that NA exerts a debilitating influence on mindfulness strategies. Taken together, these findings suggest that interventions designed to improve psychological resources, like mindfulness, should equally attend to mitigating negative emotions because their presence seems to attenuate the ability to enact the adaptive strategies embodied in trait mindfulness.

State vs. trait mindfulness and limitations of the present study

An important distinction noted in this paper is that we studied trait mindfulness in this project, whereas mindfulness enhancement interventions (such as MBSR) tend to focus on improving state mindfulness. It is not clear how PA and NA impact trait mindfulness as opposed to state mindfulness, which limits the ability of researchers to draw conclusions from a literature that includes both types of mindfulness. It also is not clear how the findings of a longitudinal study such as the present one generalises to expected findings from an MBSR intervention. Methodological clarification of state- and trait-like aspects of mindfulness needs to be made before we can usefully translate findings from one mode (e.g., MBSR interventions) to another mode (e.g., daily diary studies).

We found evidence for PA being a precursor to one FFMQ facet and NA being a precursor to three other FFMQ facets: what other precursors to trait mindfulness can we identify? While there is extensive research on the effects of trait mindfulness on psychological health, the precursors of this trait are much less understood. Armitage et al. (2015) found that lower levels of stress, negative emotionality, and internalizing difficulties predicted higher levels of trait mindfulness. Quaglia et al. (2016) notably found that mindfulness training predicts higher trait mindfulness, which points out an important link between state and trait versions of mindfulness. Other likely candidates include effective emotion regulation strategies, gratitude, and hope, but further research is needed to better understand the origins of this human capacity.

We also acknowledge several limitations in the research reported here. First, we examined a time period of three months; future work should take measurements over a longer period of time to see whether the present findings generalize to time periods of a year or longer. Second, although our sample was sizeable, our sample size was insufficient to examine all five mindfulness facets simultaneously in a single path model. Given the typical moderate to high associations among the five facets (Baer et al., 2006), it is possible that some of our facet-level findings will not hold up once shared variance among facets is taken into account. And third, in the same way that mindfulness is conceptualised to be constituted by multiple facets, it is also possible that examining finer-grained aspects of PA and NA may lead to further refinement of the questions considered here. For example, how are hedonic and contra-hedonic emotion motives (i.e., motives to experience or to avoid experiencing future NA and PA, see Bloore et al., 2020) related to mindfulness? New work in this vein (Jose et al., in preparation) suggests that mindfulness positively predicts daily striving to experience positive emotions, but, notably, in this work mindfulness was found to be unrelated to striving to avoid experiencing negative emotions, reflecting the strategy of not denying or avoiding NA generally. Clearly, mindfulness, used as an emotion regulation strategy, is nuanced and much more needs to be known about this complex collection of emotion regulation strategies.

Conclusions

In our subject variable longitudinal study, we found that overall within-subject mindfulness scores predicted decreased within-subject negative affect over three months’ time, and in the reverse direction, within-subject negative affect predicted decreased overall within-subject mindfulness. A set of exploratory analyses at the facet level suggested that all FFMQ facets predicted reduced NA over time, and NA, in turn, predicted reductions in three aspects of mindfulness (non-reacting, acting with awareness, and describing) in these temporal relationships. Taken together, these findings suggest that trait mindfulness is effective in reducing NA over time, however, these constructs operate within a feedback loop such that NA significantly reduces trait mindfulness over time as well. In contrast, mindfulness was not found to generally improve PA, and, in a reverse direction, PA had little impact on the employment of mindful strategies. We conclude that trait mindfulness seems to impact NA more than PA over three months’ time.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the OSF repository: https://osf.io/p5xuf/files/.

References

Amos Development Corporation. (2020). IBM Amos Ver. 29.0. McLean, VA: IBM SPSS.

Andersen, H. K. (2021). Equivalent approaches to dealing with unobserved heterogeneity in cross-lagged panel models? Investigating the benefits and drawbacks of the latent curve model with structured residuals and the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000285

Armitage, J., Allen, N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. (2015). Developmental precursors of dispositional mindfulness in adolescence Paper presented at the European Conference on Developmental Psychology, Braga, Portugal.

Baer, R., Smith, G., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241.

Blanke, E. S., Riediger, M., & Brose, A. (2018). Pathways to happiness are multidirectional: Associations between state mindfulness and everyday affective experience. Emotion, 18(2), 202–211.

Blanke, E. S., Schmidt, M., Riediger, M., & Brose, A. (2019). Thinking mindfully: How mindfulness relates to rumination and reflection in daily life. Emotion, 20(8), 1369–1381. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000659

Bloore, R., Jose, P. E., & Roseman, I. J. (2020). General emotion regulation measure (GERM): Individual differences in motives of trying to experience and trying to avoid experiencing positive and negative emotions. Personality and Individual Differences, 166, 110174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110174

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Byrne, B. M., & van De Vijver, F. J. R. (2010). Testing for measurement and structural equivalence in large-scale cross-cultural studies: Addressing the issue of nonequivalence. International Journal of Testing, 10(2), 107–132.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255.

Chowdhury, M. R. (2019). The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Web-site accessed on 11/19/22: https://positivepsychology.com/five-facet-mindfulness-questionnaire-ffmq/

Christopher, M. S., Neuser, N. J., Michael, P. G., & Baitmangalkar, A. (2012). Exploring the psychometric properties of the five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 124–131.

Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 245–265.

Erisman, S. M., & Roemer, L. (2010). A preliminary investigation of the effects of experimentally induced mindfulness on emotional responding to film clips. Emotion, 10(1), 72–82.

Erisman, S. M., & Roemer, L. (2012). A preliminary investigation of the process of mindfulness. Mindfulness, 3(1), 30–43.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. London: Sage.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300–319.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences, 359, 1367–1378.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19(3), 313–332.

Fredrickson, B., Cohn, M., Coffey, K., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062.

Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B. L., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S., & Penn, D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 849–864.

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015a.1064294

Garland, E. L., Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., & Wichers, M. (2015). Mindfulness training promotes upward spirals of positive affect and cognition: Multilevel and autoregressive latent trajectory modeling analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 15.

Giluk, T. L. (2009). Mindfulness, big five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 805–811.

Glück, T. M., & Maercker, A. (2011). A randomized controlled pilot study of a brief web-based mindfulness training. Bmc Psychiatry, 11, 175. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-175

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

Harp, N. R., Freeman, J. B., & Neta, M. (2022). Mindfulness-based stress reduction triggers a long-term shift toward more positive appraisals of emotional ambiguity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(9), 2160–2172. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001173

Heeren, A., & Philippot, P. (2011). Changes in ruminative thinking mediate the clinical benefits of mindfulness: Preliminary findings. Mindfulness, 2(1), 8–13.

Jimenez, S. S., Niles, B. L., & Park, C. L. (2010). A mindfulness model of affect regulation and depressive symptoms: Positive emotions, mood regulation expectancies, and self-acceptance as regulatory mechanisms. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(6), 645–650.

Johnson, L. K., Nadler, R., Carswell, J., & Minda, J. P. (2021). Using the broaden-and-build theory to test a model of mindfulness, affect, and stress. Mindfulness, 12, 1696–1707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01633-5

Jose, P. E., Gamba, C., Bloore, R. A., & Roseman, I. J. (in preparation). How does mindfulness predict what emotions people want to feel and what emotions they actually feel? Unpublished manuscript.

Jury, T., & Jose, P. E. (2019). Does rumination function as a longitudinal mediator between mindfulness and depression? Mindfulness, 10(6), 1091–1104.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte Press.

Keng, S., & Tong, E. M. W. (2016). Riding the tide of emotions with mindfulness: Mindfulness, affect dynamics, and the mediating role of coping. Emotion, 16(5), 706–718.

Mandal, S., Arya, Y., & Pandey, R. (2012). Mental health and mindfulness: Mediational role of positive and negative affect. SIS Journal of Projective Psychology and Mental Health, 19, 150–159.

McLaughlin, L. E., Luberto, C. M., O’Bryan, E. M., Kraemer, K. M., & McLeish, A. C. (2019). The indirect effect of positive affect in the relationship between trait mindfulness and emotion dysregulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 145, 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.03.020

Mulder, J. D., & Hamaker, E. L. (2021). Three extensions of the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Stuctural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28(4), 638–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1784738

Quaglia, J. T., Braun, S. E., Freeman, S. P., McDaniel, M. A., & Brown, K. W. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for effects of mindfulness training on dimensions of self-reported dispositional mindfulness. Psychological Assessment, 28(7), 803–818.

Quoidbach, J., Berry, E. V., Hansenne, M., & Mikolajczak, M. (2010). Positive emotion regulation and well-being: Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 368–373.

Raes, F., & Williams, J. M. G. (2010). The relationship between mindfulness and uncontrollability of ruminative thinking. Mindfulness, 1(4), 199–203.

Seear, K. H., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2012). Efficacy of positive psychology interventions to increase well-being: Examining the role of dispositional mindfulness. Social Indicators Research, 1–17.

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice‐friendly meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487.

Snippe, E., Nyklíček, I., Schroevers, M., & Bos, E. (2015). The temporal order of change in daily mindfulness and affect during mindfulness-based stress reduction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62, 106–114.

Trochim, W. M., & Donnelly, J. P. (2006). The research methods knowledge base (3rd Edition). Cincinnati, OH: Atomic Dog.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96(3), 465–490.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Weinstein, N., Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). A multi-method examination of the effects of mindfulness on stress attribution, coping, and emotional well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 374–385.

Wu, K., & Chang, E. C. (2019). Feeling good—and feeling bad—affect social problem solving: A test of the broaden-and-build model in Asian Americans. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000129

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jose, P.E., Geiserman, A. Does mindfulness improve one’s affective state? Temporal associations between trait mindfulness and positive and negative affect. Curr Psychol 43, 9815–9825 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04999-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04999-y