Abstract

Effective policing is essential for reducing crime and ensuring public safety. As part of their role police officers are regularly exposed to traumatic incidents. Without adequate support, prolonged exposure to such events can lead to a deterioration in a police officer’s mental health. As a result of police culture, more specifically the negative attitudes towards seeking help for mental ill-health, many police officers suffer in isolation. This can lead to serious mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We interviewed 12 former police officers with an average of 26 years in service, regarding their experiences of police culture and how this relates to mental health. We found that although a macho culture (and stigma) exist within policing, attitudes towards mental health appear to be slowly changing. The role of policing has changed in recent years due to increased awareness of mental ill-health. We discuss how this impacts the general wellbeing of police officers, and what this might mean for the future of policing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Effective policing involves a range of tasks including public reassurance, crime control, crime investigation, emergency responding, and peace-keeping (Bowling, 2007; Reiner, 2010). To maintain sufficient standards (Bowling, 2007) police must be resilient to the job demands, appropriately trained, and willing to seek support. This is especially important when considering exposure to critical incident such as motor vehicle accidents, domestic violence, crowd control, physical assaults, handling dead bodies, and dealing with unpredictable, dangerous, and armed criminals (Carlier et al., 2000; Toch, 2002). Yet, the wellbeing of police officers is generally considered to be quite poor (Foley et al., 2021). This is unsurprising given their increased exposure to trauma, stress, and critical incidents (Jenkins et al., 2019; Neylan et al., 2002; Webster, 2013). Approximately 92% of police officers deal with critical incidents within the first two years of job (Wagner et al., 2019; Inslicht et al., 2011).

Exposure to such environments is linked to poor mental health (Liberman et al., 2002; Papazoglou, 2013; Regehr et al., 2021). Often police officers are reluctant to acknowledge or process their experiences (Heffren & Hausdorf, 2016). This is partly due to the ‘macho’ subculture associated with policing (Fragoso & Kashubeck, 2000) which places emphasis on toughness, virility and masculinity (Manning, 1998). This is problematic as these masculine values led to a culture which suppresses emotional responses to trauma (Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019) and are associated with high levels of anxiety and low self-esteem (Sharpe & Heppner, 1991).

This inability to seek support results in many officers suffering from serious mental health problems (Lawson et al., 2012; Reavley et al., 2018; Wickramasinghe et al., 2016). For example., police officers are at greater risk of developing depression (Copenhaver & Tewksbury, 2018; Hartley et al., 2011) and are four times more likely (than the general public) to develop severe mental health conditions such as PTSD (Foley & Massey, 2021; Green, 2004).

Additionally, police officers face organisational pressures such as long shifts, inadequate resources, a lack of support, and increased public demand (Purba & Demou, 2019; Wang et al., 2010). As a result of these organisational stressors police officers are vulnerable to depression and other mental illnesses (Hartley et al., 2011; Santa Maria et al., 2018; Sherwood et al., 2019). Many police officers report that their work is highly stressful (Boag-Munroe, 2017), which can lead to occupational burnout (Cieslak et al., 2014; McCarty & Garland, 2007). Burnout can be thought of as a complex reaction to highly challenging and difficult situations which are the result of work (Walsh et al., 2013).

A survey conducted by Mind (2015) found that 61% of police officers experienced some form of mental health problem while at work. Despite many police officers (91%) reporting frequent stress and poor mental health, they were unlikely to take time off work (Cabinet Office, 2015). Recently, Stevelink et al. (2020) investigated the mental health of 40,299 UK police officers. They found that police officers commonly displayed symptoms of depression, anxiety and PTSD, consistent with both Norwegian (Berg et al., 2006) and American forces (Andrew et al., 2008).

One explanation for increased mental health problems within this profession is the culture (Rufo, 2017; Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019). Police culture emphasises the importance of emotional self-control and masculinity (Edwards & Kotera, 2020). As a result, officers are expected, by their peers, to suppress their emotions and to appear tough (Evans et al., 2013; Schaible & Six, 2016). Anything which deviates from this is usually viewed as weakness, and could affect their career (Bikos, 2020; Bullock & Garland, 2018). This stigma is a commonly reported reason for why many officers avoid seeking help regarding their mental health (Corrigan et al., 2014).

Organisational culture and a lack of support are key contributors for stress in police officers (Collins & Gibbs, 2003). Many police officers avoid discussing their mental health over fear of being marginalised (Bell & Eski, 2016) and instead seek help from general practitioners (Cohen et al., 2019). However, support is made available to police after a critical or traumatic incident. This is typically through a welfare led process known as Trauma Risk Management ‘TRiM’.

TRiM is a UK based peer-support programme designed to reduce the stigma towards mental health in the police and armed forces (Frappell-Cooke et al., 2010; Greenberg et al., 2008), and is often used after a serious incident due to the knowledge that exposure to traumatic events can lead to the development of long-term psychological problems. In other words, TRiM is the force’s response to minimise that risk. Police officers who have used TRiM reported less symptoms of PTSD, reduced stigma, and healthier help-seeking behaviour than the control group (Watson & Andrews, 2018). This demonstrates the success of peer-support programmes at reducing stigma and encouraging healthier attitudes towards mental health, and yet reports of mental health conditions and burnout are common (Foley & Massey, 2020; Purba & Demou, 2019). Van der Velden et al. (2010) proposed support should not just be available after a traumatic incident, it should be available on a day-to-day basis for police officers to use. Based upon the above theoretical considerations, other factors such as limited resources, a lack of support, and increased job demands can also contribute to psychological distress in police officers.

This research will explore police culture and how it can contribute to mental illness using insights from former police officers. Many police officers struggle to discuss their mental health and organisational pressures while currently in employment. Based upon a review of the literature, the researchers felt that retired or former police officers would be more likely to openly discuss operational pressures (such as a lack of resources), management conflicts, limitations of mental health support provisions, and the impacts this career has had on their personal lives. Our findings are taken from interviews with 12 former police officers with a range of experience from 6 to 31 years in service.

Method

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the criminology ethics committee at the University of Portsmouth prior to data collection. Participants were invited to take part in our interviews and were firstly provided with an information sheet and consent form to allow them to make an informed decision about the research. If interested in the research, participants provided written consent via email. Participants were informed that they would remain anonymous and that any identifiable information (i.e., names, specific police forces) would not be retained.

Design

This research involved semi-structured interviews focusing on mental health and the policing culture using former UK police. Former (i.e., retired) police officers were the target sample. There were no other specific inclusion or exclusion criteria. Our approach was consistent with previous studies investigating police officers’ lived experiences using semi-structured interviews (e.g., Lumsden, 2017; Huey & Ricciardelli, 2015; Edwards & Kotera, 2020).

Participants

Twelve former police officers (including one Chief Inspector of Operations) were interviewed. Participants (10 males and 2 females) had experience in various roles including firearms, major crimes, response teams, royalty protection and working with vulnerable persons. Most officers discussed multiple roles within their career. The years of service ranged from 6 to 31 years, with an average of 23 years.

Procedure

A call for former UK police officers was placed on the researcher’s social media platforms (e.g., Twitter and LinkedIn). Potential participants were invited to learn more about the research via email. Those who were interested in learning more about the research were sent a detailed information sheet outlining the interview and the objectives. Those who wished to take part provided written consent and were invited to an online interview using Zoom. Participants were informed that the interview would take up to an hour of their time.

A semi-structured interview guide was created with questions relating to: their policing background; police culture and mental health; views on current and past stigma; and thoughts on seeking well-being support. Follow-up questions were also used where appropriate. The interview questions were developed by the research team, which included a psychologist who specialised in interviewing. It is important to note that these questions were an interview guide and due to the flexibility of a semi-structured approach the interviewer was able to encourage a two-way communication (Table 1).

The first phase of the interview included a rapport building phase to build trust and to ease participants into discussing sensitive subjects (Abbe & Brandon, 2014; Bell et al., 2016). Rapport can be established through a range of interviewer behaviours, including displaying attentive behaviour (or demonstrating active listening), finding common ground (such as identifying mutual interests or finding similarities), demonstrating courteous behaviour and connecting with the person (through engaging in friendly interactions and using humour where appropriate). All interviews began with allowing time for the interviewer to get to know the participant. This involved a recap of what the research would involve, as well as some general information about the interviewer. The interviewer was a student who was interested in becoming a police officer, which may have introduced some bias.

To minimise bias a semi-structured interview was used. This means that the bias of the interviewer does not determine the questions asked. For consistency the same interviewer was used in all 12 interviews. On average interviews took 33 min, ranging from 24.54 to 40.00 min. After the interview participants were thanked for their time and debriefed about the research.

Thematic analysis

Qualitative research is an important process for capturing rich data, particularly as this allows for a person centred, and holistic perspective. As recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006) a thematic analysis was conducted. The thematic analysis was carried out by two researchers. One who conducted the interviews and one who was independent from the interviews to reduce any potential experimenter bias, and to promote discussion. Braun and Clarke (2021) suggest that coding with another researcher and comparing analytic observations can lead to enriched coding.

The process we used involved a superficial reading of the texts for familiarisation. In this phase, the researchers independently listened to the recording again and read the interview several times, taking notes of their reflections, bearing in mind that each rereading could reveal new interpretative ideas. Developing themes were identified starting from the notes taken during the first phase and initially discussed. Together we then formulated subthemes and agreed upon terminology and meaning. Finally, we clustered subthemes and used them to create a thematic map as outlined below.

Results

Two core themes were identified: (i) police culture, and (ii) the mental health of the police.

Police Culture

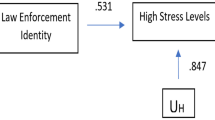

A thematic analysis based on police culture was conducted for two reasons. Firstly, several features of police culture such as masculinity, cynicism and solidarity are linked with poor mental health in the workplace (Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019). Secondly, police culture creates an in-group identity and encourages an intolerance for weakness (Bell & Eski, 2016) which can contribute to the development of mental ill-health. As presented in Fig. 2, police culture has a direct effect on police officers’ sense of identity and their perceptions towards mental health (Fig. 1).

All 12 former police officers discussed the existence of a police culture during their interviews and most believed police culture has a negative impact on mental health.

Macho culture

Macho culture places an emphasis on toughness, virility, and masculinity (Manning, 1998) and is acknowledged as part of the policing community (Fragoso & Kashubeck, 2000).

…people do hide it, because they don’t want to let it out, especially in the police environment where everything is a bit macho. People go around acting macho, but that’s the perceived notion you’re doing what can be a tough job, you’re heavily criticised and you’ve got to put up this front that it doesn’t bother you.

Seven former police officers described their work environment as ‘macho’ and implied this was a reason why police officers struggled to openly discuss their mental health. They were expected to brush things off and to maintain a tough attitude to prevent being seen as weak by their colleagues. Many officers used phrases like ‘man-up’ or discussed how they just had to ‘get over’ a hard day.

This macho culture can be particularly challenging for female police officers who are often perceived as less able to do the job (Chan et al., 2010), and who are expected to retire sooner than men. One former female police officer, who’s husband also worked in the UK police, discussed negative interactions that she had with a senior male colleague which occurred at two different police forces. She went on to explain that despite being an experienced police office, she felt discriminated against for being a female.

Well, as a female…. there were different rules, so if you’d have been a 40-year-old guy they wouldn’t have bothered. [At] 32 I was [perceived as] far too old for the police force. Coming in as a female it didn’t matter about my experience.

Unaccepting of weakness

Police culture is regarded as being unaccepting of weakness and as such encourages officers to suppress their feelings and avoid seeking help. This was consistently reported by participants.

You wouldn’t want to be labelled as a weaker member of the team mentally. That might stop people coming forward. That is a big thing. You know, in the eyes of your colleagues, you’ve got to be able to be to be trusted in all situations.

All participants in our interviews felt able to talk about their colleagues’ attitudes towards mental health, and consistently agreed that some of their colleagues displayed negative opinions. This is problematic because those suffering from poor mental health are often viewed as weak and unreliable (Karaffa & Tochkov, 2013; Toch, 2002).

Exposure to trauma

Exposure to trauma and the different types of incidents that the police encounter led to the belief that this was part of the job.

You were told you were Superman. You were, you know, bullet-proof. You came in swinging today and then you’re expected to just get on with it, you know. One minute you could be dealing with telling someone that someone’s died. Next call could be someone killed in a car accident.

Eight former police argued that responding to traumatic incidents was part of the job description, and that dealing with stress and trauma was part of being a police officer. One participant felt that as police officers they should be mentally prepared for trauma, and if people cannot cope with it, they should not be in the profession.

Work-life balance

Work-life balance refers to the equilibrium between personal life and career work. To successfully achieve a work-life balance, the various domains in a person’s life, such as family care, personal time, and work must be maintained with a minimum level of conflict (Clark, 2000; Parkes & Langford, 2008; Ungerson & Yeandle, 2005). UK police officers often recall a difficulty with maintaining a separation between their work and home life (Kumarasamy et al., 2016; McDowall & Lindsay, 2014), which can lead to conflict at home. We found evidence for this in our data, although we did not ask direct questions about their work life balance.

I think a lot of police officers find their partners are their release or escape valve. Which might be why historically police officer relationships haven’t been that good and there has been high incidents of divorce.

Not all police felt they brought work home with them. Three participants talked about how they would not discuss work outside of work.

I never came home and told anybody about what I had done. Some people do, some people tell their wives their husbands, girlfriends etc. what they did during that day, but I never did that. I believed that is work, I will keep it at work.

For those who struggled to maintain a healthy work-life balance, this often led to family conflict and increased stress (Rathi & Barath, 2013). Family conflict can occur when a police officer’s commitment to their family role is challenged due to their commitment to work (Howard et al., 2004), which is often the case for police. We found evidence of this in our data.

My wife was eight and a half months pregnant, you know, ready to give birth at any point. This is our first child. So obviously I imagine that there was a lot of stress around that… I got told go and pack your bags you’re going away for twenty-four hours. Well, twenty-four hours turned into two weeks. And when I was kind of like, you know, my wife is about to give birth and stuff, I was not directly told, but indirectly told that, well the job comes first.

Three former police discussed difficulties with their home life when beginning retirement. Two participants felt that this was a difficult transition due to the differences between the policing role and home life.

I’m probably closer to my colleagues than to some of my family. Erm when I left the police I almost had to introduce myself to my actual family again. Because I spent most of my time on duty and obviously on duty I’m socialising with colleagues.

This difficulty transitioning from work to retirement involved changes in daily, weekly, and monthly routines. Police work involves shift work (a combination of day and night time working) which often leads to a restructuring of an individual’s routine.

I’ve been retired for a few years now. I still can’t get used to the fact that there’s a weekend. That weekends exist is bizarre to everybody else but for thirty odd years I didn’t have weekends, I just had earlies, lates, and nights, or a day off. So, whether it’s a Saturday, Sunday or a Wednesday, it didn’t matter to me.

Underappreciated

Feeling underappreciated by both the police service and the public can be problematic as it leads to reduced morale and low job satisfaction, and an us versus them mentality (Brough et al., 2016). Three participants in our interviews discussed this, despite no questions linking to underappreciation.

You can very much be treated as just another number; it is getting better, a lot better than when I was in it, you were almost expected to just go and do your job and if you’re not there someone else will do it. You almost feel like just a commodity that you’re just there doing it.

Two participants expressed frustration over a lack of appreciation and understanding from the public towards police officers. Both participants felt that such a negative attitude towards officers was unjust.

People that aren’t in the police don’t quite understand what you have to deal with. They get their impressions of policing from the TV, where everything is solved within an hour or a couple of episodes and you don’t see what goes on in the background, I think sometimes people don’t want to know. There is also a growing trend just to be negative towards policing and I know it used to get myself and my colleagues down.

Social media was discussed in two of the interviews as having a negative effect on how the general public view policing. In one discussion a former police officer talked about how the media often use an isolated incident to betray the whole organisation as being negative, consistent with previous literature (Deuchar et al., 2019; Hinds, 2009).

In-group identity

Policing creates with a strong sense of in-group identity (Brough et al., 2016). One reason for this is that officers encounter traumatic incidents which other individuals struggle to relate to, creating an in-group mentality. This forms on the basis that members share a collective perception of themselves, this can develop through shared experiences (Molenberghs, 2013; Turner, 1984).

I can’t explain to you how I feel turning up to the scene of a multi-vehicle accident, but another cop would understand… I try to explain to my mates outside the job, but it is different talking to them and talking to people who’ve experienced it with me.

Seven former police felt that only an officer could understand their experiences (consistent with Brough et al., 2016). One former officer described the police as almost having their own ‘language or jargon’ which allowed for effective (and exclusive) communication amongst them.

Generation Clash

Attitudes and awareness of mental health are improving in the general public (Livingston et al., 2013). As a result, when new officers join the police service they are likely to bring new views on mental health, which can result in a generational clash (Flamant, 2007). This is because experienced officers tend to carry different views than the newer officers (Karp & Stenmark, 2011). In our sample, we had a group of participants with a long service history (seven former police had 30 or more years of service, three had between 10 and 29 years of service, and only two people had less than 10 years’ experience [6 and 9 years of service]) ranging from the late 1970’s to early 2017.

New people are joining with slightly different ideas. But sometimes it takes a little longer for those ideas to filter through. But that is where most of the change in the police service probably happens. Rather than top down, as in senior management issuing instructions, it was a cultural change because new officers come in that have got different attitudes about different things.

Eight participants in our interviews discussed how attitudes towards mental health were improving, but that some police views remained unchanged. Instead, they continued employing an unhealthy approach to dealing with trauma.

You would still have officers who wanted to appear like they were in suits of armour, that they were able to deflect or absorb anything, so you would still have individuals that would be like that. That was part of their personality.

This creates a divide between younger officers who are open to the discussion of mental health and senior officers who do not acknowledge it. One participant felt that mental health was being overused within society.

There was no such thing as mental health. If you like. Well, there was obviously but there was nothing like there is today. Yeah, people throw mental health around now all over the place.

Mental Health

As presented in Fig. 2, attitudes towards mental health within the UK police appear generally negative. This is not surprising as police culture creates a negative stigma towards mental health and seeking support. This prevents many police from discussing mental health out of fear they could be viewed as weak, or due to potential harm to their career (Edwards & Kotera, 2020). We found this was the case with the addition of some police who failed to acknowledge the importance of mental health as a contemporary problem.

All participants in this study agreed police officers were vulnerable to poor mental health. Only one person felt that this was in rare cases. This section highlights some conflicting opinions.

Some of the participants appeared more open to a lengthy discussion about mental health in the police compared to others. Seven of the participants who were more open to discussing mental health believed that police culture could be a factor in the poor mental health of officers. Interviewees discussed their experiences of traumatic incidents, and many reflected upon colleagues who suffered with PTSD as a result of their job.

I had some involvement in supporting colleagues who suffered from PTSD. And stress from dealing with quite traumatic incidents and also supporting some who had to leave the police because of the things they’d seen and experienced.

Stressful job

Work related stress was a core theme amongst all former police, many of whom focused their discussions around responding to critical incidents. One participant described how this changed over the duration of his career.

If you are running into a situation where everybody else is running away. Then there is a perfect apprehension of what might happen to you. Now in the early days you just kept running because you [felt you] are going to live forever but as I got older I was more aware. For example, if I was driving a car and I get a 999 call to a punt shop or a riot or something like that - I could be put in hospital for the rest of my life, or killed.

Despite exposure to trauma, two participants remained unsympathetic. One participant believed policing personnel knew what they were signing up for and should therefore expect this as part of their role. Another participant suggested if an officer cannot handle the stress, they should simply find a new occupation.

…people just deal with it. If you can’t, if you don’t like dead bodies, or you don’t like people with their arm or limbs hanging off, and then you don’t become a copper. You got to sort of expect that as part of the landscape.

Resilience

Resilience has been defined as a person’s capacity to cope and adapt when facing a stressful life event (Pooley & Cohen, 2010). Police are expected to display resilience after traumatic incidents since failing to do this could be seen as a sign of weakness (Balmer et al., 2014).

I’ve got no issues. As I say, I keep coming back to this mental robustness. It really is a big thing. So, you’ve seen loads of sites, and they do make you think twice. But they don’t make you lose any sleep over it at all.

Nine former police described an expectation to toughen up and move on after a stressful event. Four proposed police officers are not affected by mental illness because they are mentally prepared for these traumatic incidents. One participant suggested that this expectation could be a cause of poor mental health. Another former officer felt that team resilience was created through experienced senior officers, and that the newer generation of police officers really lacked this experience.

The teams I was on in the 80s and into the 90s, there was always some cops who had 15–20 years’ service, who had experienced things. Because they’d experienced it, they knew almost how to deal with it for you. So, you gained a lot of your strength and resilience from them… Policing is suffering from that massively at the moment, the average service profile of most cops across the UK is something like 5–10 years of front-line policing. When I had 5-year service I think I was still like the second or third youngest in service who was on my team. You walk into any response team now and 5-years of service puts them near the top. They’re in the top 10% on their team of experience. For me they still haven’t experienced a vast number of difficult challenging incidents. They haven’t themselves worked out or gained strength to deal with these difficult incidents.

Not discussed

Avoiding discussions about mental health is common in emergency responders (Dowling et al., 2005; Fogarty et al., 2021). We also found support for this in our data.

…it does stay in your head. It almost comes down to from a mental health perspective, have you got the personal capacity, or have you built your own bridges. You can put certain incidents in like a box, lock it away in your head. Leave it at work and don’t bring it home. That’s really easy to say, some people are more adept to doing that than others.

Eight participants reported that mental health was not discussed openly enough in the police service. After responding to a traumatic incident officers would refrain from talking and instead continued acting unaffected regardless of how they were actually feeling (Burke et al., 2007).

They cannot speak openly about what they’ve dealt with and how it’s impacted them because it’s seen (1) as a weakness and (2) as not professional enough or suitable for the role. No doubt even these days there are police officers who are reluctant to speak about incidents they are involved with because it will be viewed negatively against them.

Four participants suggested a lack of openness regarding mental health could be due to a fear of stigma and a perception that they are no longer suitable for their role (Bell & Eski, 2016; Edwards & Kotera, 2020).

Fear

Police culture can foster negative attitudes towards mental health. Consequently, police officers fear the perceived consequences of being associated with having mental health problems (Bell & Eski, 2016). When discussing mental health nine former police felt affiliation with mental illness could be seen as a weakness, and five people felt this could lead to discrimination from colleagues. Six participants expressed concern over mental illness harming their career, and one person talked about how a record of mental illness can prevent future promotions.

HR our human resources, it was always said do not let HR find out about this or that, because once they have got it on record they will be in to you and it will basically mess up the rest of your career.

Five participants were concerned their colleagues would not believe them if they said they were suffering from a mental illness, and two participants felt their colleagues would instead judge them and think it was an excuse for early retirement.

I didn’t want to be discharged on medical grounds because that was really not seen as a good thing among your peers, you know, you’re a bit of a pariah.

Loss of Trust

The stigma associated with mental health creates discrimination when judging the suitability of individuals for their job role (Stier & Hinshaw, 2007). This creates pressure for police officers to act emotionally stable. Consequently, those who show signs of emotional vulnerability may lose their colleague’s trust (Bell & Eski, 2016).

To come out and say that you have got some kind of mental health issues, you would probably lose that role…they would take you off that role because you would then become a liability potentially, because you are not concentrating, or something might happen.

One participant who had worked in a firearms team throughout his career explained that officers are in dangerous situations and need to be able to rely on each other. If an officer was not at full mental capacity whilst at work that could put everyone at risk.

Lack of awareness

Police officers who suffer from a mental illness are not treated with the same sympathy and respect as officers who are suffering from a physical illness (Edwards & Kotera, 2020). Part of this is due to a lack of mental health awareness.

It wouldn’t take a massive leap to realise that if you experience bad things then you might have bad thoughts. I just don’t think it was acknowledged. Everyone just went and did their job and I think there is probably a culture of not delving too deep. Because you can uncover all sorts of things that are a bit unpleasant.

Four former police suggested mental health may not have been recognised whilst they were in service. Mental health was often viewed as something they dealt with in the public rather than something they could suffer from themselves. Officers avoided dwelling on their own mental health and demonstrated limited awareness regarding the mental health of their colleagues.

Suicide in the police

Two participants highlighted the prevalence of suicide in the police despite no direct questions covering this topic. They both felt that their colleagues had committed suicide due to mental health related issues.

… you don’t see the signals. A lot of the time it is hidden behind the bravado, you know, it’s just not yet spoken about. Two of my team colleagues have committed suicide.

Coping strategies

Policing is a stressful occupation and officers must adopt successful coping strategies in order to deal with job pressures (Brough et al., 2016; Can & Hendy, 2014). Dark humour, also known as gallows humour, is employed by officers in response to traumatic incidents (Scott, 2007). This is an effective strategy that can reduce the effects of stress and trauma on officers.

If something happened that was horrible you just got on with it, you would normally have a sick joke about it, that was like a release mechanism. You come up [and] someone would say something, you might have just been to a horrible road accident. Someone will say something funny, but they didn’t mean it to be funny, it was just a release.

Nine former police discussed the importance of dark humour as a strategy for dealing with difficult situations. It was believed the ability to laugh about an otherwise horrific situation with their colleagues enabled officers to process the events and to recover from responding to traumatic incidents.

You have to bond together to survive. You’re like a team, know what I mean. If you turn up and something’s going really wrong, you rely on your colleagues, other people in uniform to help you out.

Furthermore, ten participants claimed talking things through with their colleagues was important to protect their mental health. Debriefs were recognised as effective tools that can protect officers from negative psychological outcomes after responding to traumatic incidents, and therefore should be encouraged.

Changing attitudes

Eleven former police officers noticed a change in attitudes towards mental health. Part of this is due to changes in job demands and the availability of support for those who have responded to traumatic incidents.

They [the police service] are getting better at recognition and supporting police officers, but when I was in you worked all day in a traumatic incident, a traffic collision or you know a violent incident at someone’s house.

This was reflected in discussions regarding treatment of mental ill-health. Six participants discussed their views that people could be treated for their mental health and could later return to work.

We started to acknowledge that a person could have, erm a period of mental health concern and that wouldn’t affect their ability to be a police officer. They might just need help for a short period of time. When I started the service, it was like if you had a wobble, you were always going to be wobbly. Whereas, by the time I finished my service you could have a wobble and if you got the appropriate treatment you would be back just as good as you were before.

Eight police discussed how attitudes towards mental health had improved (Levenson & Dwyer, 2000; Edwards & Kotera, 2020). Five participants felt that officers are now more aware and more likely to access mental health support. In addition, three people believed the stigma towards mental health has decreased due to the increased awareness of mental health in society.

Interestingly, seven former police believed that their job role would be more difficult nowadays due to increased demands, social media, and a lack of senior personnel. Many discussions centred around the police supporting mentally unwell members of the public despite not being adequately trained.

There’s huge mental health issues within society and not enough is done to deal with mental health in society. So, the police become more like social workers and more like mental health professionals than police officers. We deal with a lot more mental health related calls, especially in the current situation we find ourselves in with COVID. So, lockdown significantly increased mental health related calls. Just speaking to former colleagues who are still working there. Mental health related calls have gone through the roof. They turn up to deal with more mental health related calls to support the health services, taking people into hospitals. I hardly ever did that when I was working. I would get one or two per week.

Discussion

This research explored the experiences of former UK police officers in relation to police culture and mental health. Participants recalled their experiences of being a police officer. Some former police had been retired for several years when these interviews took place. As memories are impressionable (Fadnes et al., 2009) and decay over time (Murre & Dros, 2015) we must consider the accuracy of this information. It is possible that participants only remembered some aspects of their career, which is not necessarily a true reflection of their experiences. Alternatively, as former police they may have been more willing to discuss their past experiences without fear of repercussions. Furthermore, having time and space to reflect upon their experiences can allow for a deeper understanding. During the interview, one participant discussed not noticing the negative impacts of his career until he retired.

Although this research intended to explore the personal experiences of former police officers, many participants were reluctant to talk about their own experiences and instead related discussions about their colleagues. This is perhaps due to the stigma police officers associate with mental health (Edwards & Kotera, 2020). Alternatively, it may have been easier or seemed more interesting to relate their experiences to their colleagues given the strong sense of a group identity.

In addition to a strong sense of in-group identity, we found that a macho culture existed for former police officers irrespective of their job roles or their varied length in service. Many of the values prevalent in macho culture are considered harmful for mental health (Fragoso & Kashubeck, 2000; Sharpe & Heppner, 1991). Most participants in our research recognised that these values were problematic for their own wellbeing, as well as the wellbeing of their colleagues. Despite the acknowledgement that a macho culture can be harmful for wellbeing, participants still felt that they had to suppress their emotions to avoid stigmatisation from colleagues (Karaffa & Tochkov, 2013).

A highly masculine culture can be problematic for female police officers (Burke & Mikkelsen, 2005; Silvestri, 2006). The hierarchy of male dominance in policing segregates female officers through individual actions and organisational policies and practices (Shelley et al., 2011). Research has shown that male officers often believe that women are unfit for the physical and emotional demands of policing (Chan et al., 2010). We found some support for this. One former female officer felt she was judged for being older, a judgement that she felt male colleagues would not have had.

The dominance of masculine values in police culture creates social pressure on individuals to suppress their emotions which contributes to increased stress and burnout of both male and female staff (McCarty & Garland, 2007). We found that masculine values were consistent amongst different police forces – even when former police had moved into different roles. Such values encourage individuals to avoid discussing mental health with colleagues out of fear of being stigmatised (Bell & Eski, 2016). These negative attitudes can have damaging consequences on the mental health of officers and can lead to discrimination in the workplace (Bullock & Garland, 2018).

Police culture fosters masculine values and creates a stigma towards mental health, but it can also encourage social support and resilience (Brough et al., 2016). Ten former police recalled occasions when they discussed incidents either in the canteen during their break, or afterwork in the pub which they felt helped them to process difficult situations. Downplaying the situation and using dark humour as coping strategies were reported across interviews and are consistent within the literature (Brough et al., 2016; Scott, 2007). Eight former police still believed that exposure to trauma was part of the job and one person believed that staff should be able to deal with this if they want to remain in the profession. Not all police officers held this belief, and some felt that more mental health support is needed. We also found mixed opinions towards the ability to maintain a healthy work life balance. Those able to maintain this balance felt less overwhelmed or burnt out by their job demands.

Participants in this research felt that seeking support for mental health was more effective when they used services which were not connected to the police. This was based upon a mixture of their lived experience and their discussions with other colleagues. This was partly due to the stigma associated with seeking mental health support (consistent with Corrigan et al., 2014). Although our participants discussed work related stress, many remained unsympathetic towards their colleagues who were emotionally affected by this. Some felt that responding to trauma was part of the job, and that all new officers should expect this. Furthermore, the belief that police should be resilient and able to cope with critical incidents without wellbeing support was frequently reported.

Police officers have a high workload, often encounter inadequate resources, and report feeling undervalued (Purba & Demou, 2019; Wang et al., 2010). In our sample participants reported feeling underappreciated by both the force and the general public, consistent with previous research (Brough et al., 2016; Reynolds et al., 2018). The public’s negative perception of policing can reduce morale (Deuchar et al., 2019) and a lack of recognition and support from the police service itself can increase stress (Gudjonsson & Adlam, 1985). Job satisfaction is important for reducing burnout and maintaining wellbeing. Many participants in our study claimed the police service can be a tough employer to work for due to a lack of recognition for the challenges they face. Some believed recognition had improved in recent years, but that there was still work to be done.

Extreme forms of distress can result in suicidal ideation which emerged as a theme within our data. The prevalence of suicide in the police is unclear (Violanti et al., 2019). Some researchers argue that suicide is more prevalent amongst police officers than in the general public (Violanti, 2010), while others suggest this is not the case (Marzuk et al., 2002; Schmidtke et al., 1999). One explanation for these mixed findings is that suicide is underreported in policing (Loo, 2003; Violanti et al., 2013a, b, 2019). In our sample of twelve, two officers reported having colleagues who committed suicide due to mental health problems. Despite this, the former police revealed they were unaware of their colleagues’ conditions prior to the incident. This may be an example of limited awareness, which often results in mental illnesses going undetected (Edwards & Kotera, 2020; Velazquez & Hernandez, 2019).

Generally, participants reported that they were able to bond with colleagues with similar ranks. Many felt that only another police officer could really understand their experiences and that because of this it was pointless trying to talk to family members or friends who simply cannot relate, which can lead to isolation (Brough et al., 2016; Hall et al., 2010). This leads to specific coping strategies which can help individuals to deal with traumatic incidents. For example., dark humour is often used by police officers when responding to traumatic incidents (Scott, 2007). This is an effective strategy that can reduce the effects of stress and trauma on officers. Of course, this reinforces the already strong sense of in-group identity and police specific culture, which goes some way to explain why negative attitudes towards mental health are so difficult to change.

Policing culture is thought to remain the same (Cordner, 2017), although some argue this is changing (Edwards & Kotera, 2020). Our findings suggest the latter is the case. Those who retired more recently appeared more open to support seeking and possessed a healthier view of mental health, consistent with contemporary literature (Turner & Jenkins, 2019). Most former police officers who had longstanding careers felt they noticed this shift in policing culture. We recommend that researcher’s examining police culture focus efforts on recruiting retired officers. This sample is most likely to have experienced systematic change.

Our research provides promising insights into how attitudes towards mental health appear to be changing, particularly among newer officers. Individuals joining the police force in more recent years appear to have fewer negative attitudes towards mental health (Karp & Stenmark, 2011). This is not surprising as the availability of support and awareness of support for mental health issues has increased (Carleton et al., 2018) and the stigma is reducing as new officers bring new perspectives (Cohen et al., 2019). The former police in our study reflected upon these changes and how the service was becoming more accepting of mental ill-health as a consequence of job demands. Consistent with the view that younger police officers are behind the change in attitudes, we also found from our data that senior police appeared more dismissive towards mental health. Our data revealed that some senior officers believed that mental health was an excuse to avoid hard work, and that too much emphasis is placed on supporting wellbeing. Nonetheless, this shift towards mental health may lead to future change.

Our findings provide practical importance as they highlight generational differences towards policing culture and the impact this has on mental health of police officers. However, it is important to acknowledge the context in which this data was gathered. Our data was gathered online via Zoom interviews which may have reduced rapport, resulting in less information elicitation. Consequently, in-person interviewing may have provided richer data. We gathered data from 12 former police officers who were willing to discuss their experiences. It is also possible that our self-selecting sample may have introduced bias. Nevertheless, this research does provide an insight into policing culture that may not be possible by assessing current policing staff.

In conclusion, policing culture and attitudes towards mental health are changing. We found that although barriers to seeking help for wellbeing still exist, this is becoming more acceptable within younger generations. Unexpectedly, our research highlighted a generational clash between long serving and junior members of the force. Researchers and policy makers should acknowledge this clash if they want to make effective changes.

Data availability

Materials are available upon request. The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abbe, A., & Brandon, S. E. (2014). Building and maintaining rapport in investigative interviews. Police Practice and Research, 15(3), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2013.827835

Andrew, M. E., McCanlies, E. C., Burchfiel, C. M., Charles, L. E., Hartley, T. A., Fekedulegn, D., & Violanti, J. M. (2008). Hardiness and psychological distress in a cohort of police officers. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 10(2), 137–148.

Balmer, G. M., Pooley, J. A., & Cohen, L. (2014). Psychological resilience of western australian police officers: relationship between resilience, coping style, psychological functioning and demographics. Police Practice and Research, 15(4), 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2013.845938

Bell, K., Fahmy, E., & Gordon, D. (2016). Quantitative conversations: the importance of developing rapport in standardised interviewing. Quality & Quantity, 50(1), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-014-0144-2

Bell, S., & Eski, Y. (2016). ‘Break a leg—it’s all in the mind’: police officers’ attitudes towards colleagues with mental health issues. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 10(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pav041

Berg, A. M., Hem, E., Lau, B. R., & Ekeberg, Ø. (2006). Help-seeking in the norwegian Police Service. Journal of Occupational Health, 48(3), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.48.145

Bikos, L. J. (2020). ‘It’s all window dressing:’ canadian police officers’ perceptions of mental health stigma in their workplace. Policing: An International Journal, 44(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-07-2020-0126

Boag-Munroe, F. (2017). National Detectives Survey. Reterieved from: https://www.polfed.org/media/14914/national-detectives-survey-headline-statistics-2017-report-06-10-17-v10.pdf.

Bowling, B. (2007). Fair and effective policing methods: towards ‘good enough’policing. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 8(S1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14043850701695023

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis. In E. Lyons, & A. Coyle (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data in psychology (3rd Eds.). Sage Publications Ltd.

Brough, P., Chataway, S., & Biggs, A. (2016). ‘You don’t want people knowing you’re a copper!’A contemporary assessment of police organisational culture. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 18(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355716638361

Bullock, K., & Garland, J. (2018). Police officers, mental (ill-) health and spoiled identity. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817695856

Burke, R., Waters, J. A., & Ussery, W. (2007). Police stress: history, contributing factors, symptoms, and interventions. Policing: an International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 30(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510710753199

Burke, R. J., & Mikkelsen, A. (2005). Gender issues in policing: do they matter? Women in Management Review, 20(2), 133–143.

Cabinet Office. (2015). POLICE: how to manage your mental wellbeing. Blue Light Programme. Mind.

Can, S. H., & Hendy, H. M. (2014). Police stressors, negative outcomes associated with them and coping mechanisms that may reduce these associations. The Police Journal, 87(3), 167–177.

Carleton, R. N., Korol, S., Mason, J. E., Hozempa, K., Anderson, G. S., Jones, N. A., & Bailey, S. (2018). A longitudinal assessment of the road to mental readiness training among municipal police. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(6), 508–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1475504

Carlier, I. V., Lamberts, R. D., & Gersons, B. P. (2000). The dimensionality of trauma: a multidimensional scaling comparison of police officers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research, 97(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00211-0

Chan, J., Doran, S., & Marel, C. (2010). Doing and undoing gender in policing. Theoretical Criminology, 14(4), 425–446.

Cieslak, R., Shoji, K., Douglas, A., Melville, E., Luszczynska, A., & Benight, C. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychological Services, 11(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033798

Clark, S. C. (2000). Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53(6), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001

Cohen, I. M., McCormick, A. V., & Rich, B. (2019). Creating a culture of police officer wellness. Policing: a Journal of Policy and Practice, 13(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paz001

Collins, P. A., & Gibbs, A. C. C. (2003). Stress in police officers: a study of the origins, prevalence and severity of stress-related symptoms within a county police force. Occupational Medicine, 53(4), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqg061

Copenhaver, A., & Tewksbury, R. (2018). Predicting state police officer willingness to seek professional help for depression. Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society, 19(1), 60–64. Retrieved From: https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/wescrim19&i=66

Cordner, G. (2017). Police culture: individual and organizational differences in police officer perspectives. Policing, 40(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-07-2016-0116

Corrigan, P. W., Druss, B. G., & Perlick, D. A. (2014). The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15, 37–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614531398

Dowling, F. G., Genet, B., & Moynihan, G. (2005). A confidential peer-based assistance program for police officers. Psychiatric Services, 56(7), 870–871. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.870

Deuchar, R., Fallik, S. W., & Crichlow, V. J. (2019). Despondent officer narratives and the ‘post-Ferguson’effect: exploring law enforcement perspectives and strategies in a southern american state. Policing and Society, 29(9), 1042–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2018.1480020

Edwards, A. M., & Kotera, Y. (2020). Mental Health in the UK Police Force: a qualitative investigation into the Stigma with Mental Illness. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00214-x

Evans, R., Pistrang, N., & Billings, J. (2013). Police officers’ experiences of supportive and unsupportive social interactions following traumatic incidents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 19696.

Fadnes, L. T., Taube, A., & Tylleskär, T. (2009). How to identify information bias due to self-reporting in epidemiological research. The Internet Journal of Epidemiology, 7(2), 28–38.

Flamant, N. (2007). A generation clash or organisational conflict? ‘Two trains arunning’. Sociologie du Travail, 49, 110–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soctra.2007.10.003

Fogarty, A., Steel, Z., Ward, P. B., Boydell, K. M., McKeon, G., & Rosenbaum, S. (2021). Trauma and Mental Health Awareness in Emergency Service Workers: a qualitative evaluation of the behind the seen Education Workshops. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094418

Foley, J., & Massey, K. L. D. (2020). The ‘cost’of caring in policing: from burnout to PTSD in police officers in England and Wales. The Police Journal, 20(10), 1–18.

Foley, J., & Massey, K. L. D. (2021). The ‘cost’of caring in policing: From burnout to PTSD in police officers in England and Wales. The Police Journal, 94(3), 298–315.

Foley, J., Hassett, A., & Williams, E. (2021). ‘Getting on with the job’: A systematised literature review of secondary trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in policing within the United Kingdom (UK). https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X21990412

Fragoso, J. M., & Kashubeck, S. (2000). Machismo, gender role conflict, and mental health in mexican american men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 1(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.1037//1524-9220

Frappell-Cooke, W., Gulina, M., Green, K., Hughes, H., & Greenberg, N. (2010). Does trauma risk management reduce psychological distress in deployed troops? Occupational Medicine, 60(8), 645–650.

Green, B. (2004). Post-traumatic stress disorder in UK police officers. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 20(1), 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079903125002748

Greenberg, N., Langston, V., & Jones, N. (2008). Trauma risk management (TRiM) in the UK Armed Forces. BMJ Military Health, 154(2), 124–127. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-154-02-11

Gudjonsson, G. H., & Adlam, K. R. C. (1985). Occupational stressors among British police officers. The Police Journal, 58(1), 73-80.

Hall, G. B., Dollard, M. F., Tuckey, M. R., Winefield, A. H., & Thompson, B. M. (2010). Job demands, work-family conflict, and emotional exhaustion in police officers: a longitudinal test of competing theories. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X401723

Hartley, T. A., Burchfiel, C. M., Fekedulegn, D., Andrew, M. E., & Violanti, J. M. (2011). Health disparities in police officers: comparisons to the US general population. International journal of emergency mental health, 13(4), 211.

Heffren, C. D., & Hausdorf, P. A. (2016). Post-traumatic effects in policing: perceptions, stigmas and help seeking behaviours. Police Practice and Research, 17(5), 420–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2014.958488

Hinds, L. (2009). Public satisfaction with police: the influence of general attitudes and police-citizen encounters. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 11(1), 54–66.

Howard, W. G., Donofrio, H. H., & Boles, J. S. (2004). Inter-domain work‐family, familywork conflict and police work satisfaction. Policing: an International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 27(3), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510410553121

Huey, L., & Ricciardelli, R. (2015). ‘This isn’t what I signed up for’ When police officer role expectations conflict with the realities of general duty police work in remote communities. International Journal of Police science & management, 17(3), 194–203.

Inslicht, S. S., Otte, C., McCaslin, S. E., Apfel, B. A., Henn-Haase, C., Metzler, T., & Marmar, C. R. (2011). Cortisol awakening response prospectively predicts peritraumatic and acute stress reactions in police officers. Biological Psychiatry, 70(11), 1055–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.030

Jenkins, E. N., Allison, P., Innes, K., Violanti, J. M., & Andrew, M. E. (2019). Depressive symptoms among police officers: Associations with personality and psychosocial factors. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 34(1), 67–77.

Karaffa, K. M., & Tochkov, K. (2013). Attitudes toward seeking mental health treatment among law enforcement officers. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 9(2), 75– 99. Retrieved From: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-10928-001

Karp, S., & Stenmark, H. (2011). Learning to be a police officer. Tradition and change in the training and professional lives of police officers. Police practice and Research. An International Journal, 12(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2010.497653

Kumarasamy, M. M., Pangil, F., & Mohd Isa, M. F. (2016). The effect of emotional intelligence on police officers’ work–life balance: the moderating role of organizational support. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 18(3), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355716647745

Lawson, K. J., Rodwell, J. J., & Noblet, A. J. (2012). Mental Health of a Police Force: estimating prevalence of work-related depression in Australia without a Direct National measure. Psychological Reports, 110(3), 743–752.

Levenson, R. L., & Dwyer, L. A. (2000). Peer support in law enforcement. past, present and future. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 5(3), 147–152. Retrieved From https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-09944-005

Liberman, A. M., Best, S. R., Metzler, T. J., Fagan, J. A., Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (2002). Routine occupational stress and psychological distress in police. Policing: an International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 25(2), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510210429446

Livingston, J. D., Tugwell, A., Korf-Uzan, K., Cianfrone, M., & Coniglio, C. (2013). Evaluation of a campaign to improve awareness and attitudes of young people towards mental health issues. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(6), 965–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0617-3

Loo, R. (2003). A meta-analysis of police suicide rates: findings and issues. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(3), 313–325.

Lumsden, K. (2017). Police officer and civilian staff receptivity to research and evidencebased policing in the UK: providing a contextual understanding through qualitative interviews. Policing: a Journal of Policy and Practice, 11(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paw036

Manning, P. K. (1998). Police Work: The Social Organisation of Policing, 38(3), 521–525. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23638706

Marzuk, P. M., Nock, M. K., Leon, A. C., Portera, L., & Tardiff, K. (2002). Suicide among New York city police officers, 1977–1996. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(12), 2069–2071. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2069

McCarty, W. P., & Garland, B. E. (2007). Occupational stress and burnout between male and female police officers: are there any gender differences? Policing: an International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 30(4), 672–691. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510710833938

McDowall, A., & Lindsay, A. (2014). Work–life balance in the police: the development of a self-management competency framework. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(3), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9321-x

Mind (2015). Blue light scoping survey. https://www.mind.org.uk/media-a/4583/blue-lightscoping-survey-police.pdf

Molenberghs, P. (2013). The neuroscience of in-group bias. Neuroscience & Biobehavioural Reviews, 37(8), 1530–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.002

Murre, J. M., & Dros, J. (2015). Replication and analysis of Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve. PLoS One, 10(7), e0120644.

Neylan, T. C., Metzler, T. J., Best, S. R., Weiss, D. S., Fagan, J. A., Liberman, A., & Marmar, C. R. (2002). Critical incident exposure and sleep quality in police officers. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(2), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842200203000-00019

Papazoglou, K. (2013). Conceptualizing police complex spiral trauma and its applications in the police field. Traumatology, 19(3), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765612466151

Parkes, L., & Langford, P. (2008). Work–life balance or work–life alignment? A test of the importance of work-life balance for employee engagement and intention to stay in organisations. Journal of Management & Organization, 14(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.837.14.3.267

Pooley, J. A., & Cohen, L. (2010). Resilience: A definition in context. Australian Community Psychologist, 22, 30–37. Retrieved from: https://www.psychology.org.au/APS/media/ACP/Pooley.pdf

Purba, A., & Demou, E. (2019). The relationship between organisational stressors and mental wellbeing within police officers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7609-0

Rathi, N., & Barath, M. (2013). Work-family conflict and job and family satisfaction: moderating effect of social support among police personnel. Equality, diversity and inclusion. An International Journal, 32(4), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI10-2012-0092

Reavley, N. J., Milner, A. J., Martin, A., Too, L. S., Papas, A., Witt, K., ... & LaMontagne, A. D. (2018). Depression literacy and help-seeking in Australian police. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(11), 1063–1074.

Regehr, C., Carey, M. G., Wagner, S., Alden, L. E., Buys, N., Corneil, W., & Fleischmann, M. (2021). A systematic review of mental health symptoms in police officers following extreme traumatic exposures. Police Practice and Research, 22(1), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2019.1689129

Reiner, R. (2010). The politics of the police. Oxford University Press.

Reynolds, P. D., Fitzgerald, B. A., & Hicks, J. (2018). The expendables: a qualitative study of police officers’ responses to organizational injustice. Police Quarterly, 21(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611117731558

Rufo, R. A. (Ed.). (2017). Police suicide: is police culture killing our officers? CRC Press.

Santa Maria, A., Wörfel, F., Wolter, C., Gusy, B., Rotter, M., Stark, S., & Renneberg, B. (2018). The role of job demands and job resources in the development of emotional exhaustion, depression, and anxiety among police officers. Police Quarterly, 21(1), 109–134.

Schaible, L. M., & Six, M. (2016). Emotional strategies of police and their varying consequences for burnout. Police Quarterly, 19(1), 3–31.

Schmidtke, A., Fricke, S., & Lester, D. (1999). Suicide among german federal and state police officers. Psychological Reports, 84(1), 157–166.

Scott, T. (2007). Expression of humour by emergency personnel involved in sudden deathwork. Mortality, 12(4), 350–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576270701609766

Sharpe, M. J., & Heppner, P. P. (1991). Gender role, gender role conflict, and psychological well-being in men. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 38, 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.38.3.323

Shelley, T. O. C., Morabito, M. S., & Tobin-Gurley, J. (2011). Gendered institutions and gender roles: understanding the experiences of women in policing. Criminal Justice Studies, 24(4), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601X.2011.625698

Sherwood, L., Hegarty, S., Vallières, F., Hyland, P., Murphy, J., Fitzgerald, G., & Reid, T. (2019). Identifying the key risk factors for adverse psychological outcomes among police officers: a systematic literature review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(5), 688700. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22431

Silvestri, M. (2006). ’doing time’: becoming a police leader. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 8(4), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2006.8.4.266

Stevelink, S. A., Opie, E., Pernet, D., Gao, H., Elliott, P., Wessely, S., & Greenberg, N. (2020). Probable PTSD, depression and anxiety in 40,299 UK police officers and staff: prevalence, risk factors and associations with blood pressure. PLoS One, 15(11), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240902

Stier, A., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2007). Explicit and implicit stigma against individuals with mental illness. Australian Psychologist, 42(2), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060701280599

Toch, H. (2002). Stress in policing. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10417-000

Turner, J. C. (1984). Psychological group formation’. The Social Dimension: european developments in social psychology. 2, 518 – 38. Cambridge University Press.

Turner, T., & Jenkins, M. (2019). ‘Together in work, but alone at heart’: insider perspectives on the mental health of british police officers. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 13(2), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pay016

Ungerson, C., & Yeandle, S. (2005). Care workers and work—life balance: the example of domiciliary careworkers. Work-life balance in the 21st Century (pp. 246–262). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230373594_13

Van der Velden, P. G., Kleber, R. J., Grievink, L., & Yzermans, J. C. (2010). Confrontations with aggression and mental health problems in police officers: The role of organizational stressors, life-events and previous mental health problems. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(2), 135–144.

Velazquez, E., & Hernandez, M. (2019). Effects of police officer exposure to traumatic experiences and recognizing the stigma associated with police officer mental health. Policing: an International Journal, 712–724. Retrieved From: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/1363-951X.htm

Violanti, J. M. (2010). Police suicide: a national comparison with fire-fighter and military personnel. Policing: an International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511011044885

Violanti, J. M., Hartley, T. A., Gu, J. K., Fekedulegn, D., Andrew, M. E., & Burchfiel, C. M. (2013a). Life expectancy in police officers: a comparison with the US general population. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 15(4), 217. Retrieved From: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4734369/

Violanti, J. M., Robinson, C. F., & Shen, R. (2013b). Law enforcement suicide: a National Analysis. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 15(4), 289–298.

Violanti, J. M., Owens, S. L., McCanlies, E., Fekedulegn, D., & Andrew, M. E. (2019). Law enforcement suicide: a review. Policing: an International Journal, 42(2), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-05-2017-0061

Wagner, S., White, N., Matthews, L. R., Randall, C., Regehr, C., White, M., & Fleischmann, M. H. (2019). Depression and anxiety in policework: a systematic review. Policing: an International Journal, 43(3), 418–434. Retrieved From: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/1363-951X.htm

Walsh, M., Taylor, M., & Hastings, V. (2013). Burnout and post traumatic stress disorder in the police: educating officers with the Stilwell TRiM approach. Policing: a Journal of Policy and Practice, 7(2), 167–177.

Wang, Z., Inslicht, S. S., Metzler, T. J., Henn-Haase, C., McCaslin, S. E., Tong, H., Neylan, T. C., & Marmar, C. R. (2010). A prospective study of predictors of depression symptoms in police. Psychiatry Research, 175(3), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.010

Watson, L., & Andrews, L. (2018). The effect of a trauma risk management (TRiM) program on stigma and barriers to help-seeking in the police. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(4), 348. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000071

Webster, J. H. (2013). Police officer perceptions of occupational stress: the state of the art. Policing: an International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-03-2013-0021

Wickramasinghe, N. D., Wijesinghe, P. R., Dharmaratne, S. D., & Agampodi, S. B. (2016). The prevalence and associated factors of depression in policing: a cross sectional study in Sri Lanka. Springerplus, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-34749

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute of Criminal Justice Studies (ICJS) ethics committee at the University of Portsmouth.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Participants provided informed written consent regarding the publishing of non-identifiable data.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Porter, C.N., Lee, R. The policing culture: an exploration into the mental health of former British police officers. Curr Psychol 43, 2214–2228 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04365-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04365-y