Abstract

Experiential avoidance is defined as a process involving excessive negative evaluations of difficult or unwanted feelings, thoughts, and sensations, an unwillingness to remain in contact with and express these experiences, and habitual attempts to avoid or control them. Experiential avoidance is closely associated with maladaptive functioning. Although the ability to connect with internal experiences has been considered an important element of effective leadership, this assumption has not yet been empirically tested. On the basis of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy model of experiential avoidance and the propositions of leadership models (e.g., transformational and authentic leadership) that characterize leadership as an emotion-related process, we examined the relationship between leaders’ experiential avoidance and their followers’ well-being in a sample of leader-follower triads. Well-being outcomes were subjective happiness, purpose in life, and job satisfaction. We also tested the mediating roles of followers’ basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration in this relationship. Multilevel mediation model analyses suggested that followers’ psychological need frustration but not need satisfaction mediated the relationship between leaders’ experiential avoidance and followers’ well-being outcomes. Thus, a rigid attitude toward one’s internal experiences as a leader is a risk factor for followers’ well-being because leaders with such attitudes may pay little attention to their followers and give rise to need frustration in their followers. Organizational efforts to increase leaders’ flexibility in dealing with negative experiences can help foster well-being among both leaders and their followers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Experiential avoidance (EA) is a process that is characterized by negative evaluations of difficult feelings, thoughts, and sensations and an unwillingness to remain in contact with them or express these experiences. Moreover, there are habitual attempts to avoid or control them (Hayes, Follette & Linehan, 2004, 2006). EA is a broad class of coping strategies that involve behaviors, such as suppressing an emotion or a thought; avoiding situations, people, or events that evoke a particular unwanted internal experience; or distracting oneself when distressing memories occur (Hayes, Strosahl et al., 2004). EA has been emphasized as a relevant problem in third-wave behavior therapy approaches, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which posits that habitual experiential avoidance is associated with maladaptive functioning (Hayes, Follette & Linehan, 2004).

EA has been the focus of many studies in clinical psychology, and it has been shown that this tendency is linked to decreased positive affect and increased anxiety and depression (e.g., Kashdan et al., 2006; Hayes et al., 1996; Tull et al., 2004). There have also been initial studies on EA in organizational psychology (e.g., Bond et al., 2013; Lloyd et al., 2013). However, so far, research has mostly focused on intrapersonal effects of EA, that is, its effects on a person’s own physical, personal, social, or work-related well-being. Only a few studies have investigated interpersonal effects, which are effects between individuals in close relationships (e.g., Reddy et al., 2011). To our knowledge, there has not been a study on the interpersonal effects of EA in organizational settings even though the findings from clinical research have suggested that there could be negative effects.

The present research attempted to address this gap by focusing on a real-life sample of matched leaders and followers. Many theoretical approaches have emphasized the importance of leaders’ abilities to connect with their internal experiences, such as emotions and thoughts. For example, according to ACT, whereas willingness to experience is an essential component of good leadership and may improve the quality of interpersonal relationships and organizational outcomes, controlling or avoiding emotional experiences (i.e., experiential inflexibility) has been considered detrimental to effective leadership (Moran, 2011). It has also been argued that psychological flexibility, which includes low EA, can improve the quality of interpersonal relationships at work as well as organizational outcomes (Bond et al., 2013; Moran, 2011; Reb et al., 2014). This idea is also aligned with the conceptualization of leadership as a process of social influence through which leaders can impact their followers’ cognitions, emotions, and behaviors (Humphrey, 2002, 2012). It is also aligned with the interactionist-communicative leadership approach, which posits that how leaders use and regulate their emotions influences the effectiveness of their leadership (Riggio & Reichard, 2008). Contemporary models of leadership, such as transformational leadership, also emphasize the positive effect of leaders’ effective use of emotions (see Bass & Riggio, 2006; Bakker et al., 2022).

In the present study, we explored the relationship between leaders’ EA and their followers’ well-being. Our work contributes to the emerging literature on EA at work by focusing on its interpersonal outcomes. Past research (e.g., Bond & Donaldso-Feilder, 2004; Bond et al., 2006; Lloyd et al., 2013) has shown that employees’ EA was negatively associated with their well-being at work and has thus provided some evidence of intrapersonal effects of EA in organizational settings. Here, we focus on the leader-follower relationship, which is one of the most central relationships at work. Many scholars (e.g., Gottman, 1994; Gross & John, 2003; Hayes et al., 2006) have proposed that avoidance of internal experiences can result in poor-quality relationships in general. There is indeed empirical evidence that EA can be detrimental to interpersonal functioning (e.g., Twiselton et al., 2020; Zamir et al., 2018). However, these previous studies focused on romantic relationships. By examining the relationship between leaders’ EA and their followers’ well-being outcomes, we aim to better understand the mechanisms that explain the interpersonal effects between leaders and their followers in the workplace.

Our study also extends research on leadership by specifically focusing on the concept of EA. Although empirical work has reported that leaders’ emotional intelligence (Sy et al., 2006), emotion regulation (Kafetsios et al., 2011), emotion recognition (Kerr et al., 2006), and surface and deep acting (Humphrey et al., 2008) impact follower outcomes, leaders’ EA has not been studied as a separate concept. Whereas emotion regulation, emotional intelligence, and EA are all metacognitive and meta-mood constructs that emphasize the extent to which people perceive, express, and regulate their internal experiences (Kashdan et al., 2006), EA is distinct from them in terms of its broader context, involving not only an unwillingness to remain in contact with those experiences and express them but also habitual attempts to avoid or control them (Hayes et al., 2006). Besides, EA is concerned not only with emotional processes but also thought-related processes and bodily sensations. For example, thought suppression is considered to be a form of EA (Purdon, 1999). In addition, EA involves unwanted experiences only, whereas regulation of emotions or emotional intelligence are concerned with both positive and negative emotions.

Finally, in an attempt to better understand the relationship between leaders’ EA and followers’ well-being, in accordance with self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), we explore the mediating roles of basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration in the proposed relationship. In the following sections, we explain our related hypotheses and the rationale behind them on the basis of the relevant literature.

Experiential avoidance

EA occurs when an individual is unwilling to remain connected with their internal experiences such as emotions, bodily sensations, thoughts, and memories, and attempts to change the form or frequency of these experiences (Hayes et al., 1996). EA is an overarching construct that is broader than similar emotion regulation strategies such as thought suppression and emotion suppression. It includes other behaviors that serve an avoidant function as well as a negative attitude towards negative internal experiences (Hayes, Strosahl et al., 2004).

Both the third-wave therapy approaches (e.g., Hayes et al., 2006) and the process model of emotion regulation (John & Gross, 2004) emphasize the paradox of EA in that attempts to avoid or inhibit unpleasant feelings and thoughts tend to actually increase the frequencies and levels of these experiences. In fact, there is empirical evidence that the continuous pursuit of pleasant emotions and thoughts can backfire and may lead to negative affectivity and dysfunctional behavior (Hayes et al., 2012; Stanton & Watson, 2014). On the other hand, accepting one’s inner experiences has the power to decrease the impact of distressing emotions and increase the ability to respond flexibly and not defensively (Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000).

Although avoidance strategies can have benefits under certain circumstances, they may have a detrimental effect on psychological health in the long term by promoting a narrow attentional focus and inflexible or rigid behavioral patterns (Hayes et al., 2006; Wilson & Murrell, 2004). In fact, painful thoughts or emotions are believed to be necessary in the pursuit of value-based goals as long as people are willing to accept and be in touch with them (Bond & Bunce, 2003; Pomerantz et al., 2000).

EA has been found to be associated with reduced quality of life and well-being and increased ill-being, such as anxiety, depression, and externalizing of problems (Bond et al., 2011; Kashdan et al., 2006; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Woodruff et al., 2014) as well as decreased quality of interpersonal relationships (Gerhart et al., 2014; Twiselton et al., 2020). There is also a growing body of research on people’s willingness to be in contact with their internal experiences in the work context (e.g., Bond & Donaldso-Feilder, 2004; Bond et al., 2006; Lloyd et al., 2013). For example, psychological flexibility, which is characterized by both low EA and high frequencies of value-driven and goal-directed actions, is associated with increased job satisfaction (Bond & Bunce, 2000; Bond & Flaxman, 2006), ability to handle work pressure (Bond & Bunce, 2003), and performance (Onwezen et al., 2014) and with decreased emotional exhaustion (Biron & van Veldhoven, 2012).

Leaders’ EA and followers’ well-being

ACT has proposed that low EA is an aspect of psychological flexibility that involves the abilities to (a) accept the present moment without needing to regulate the associated emotions and thoughts, (b) adapt to the situational demands of the situation, and (c) act in accordance with one’s goals (Bond & Bunce, 2003; Hayes et al., 2006). Although numerous studies in clinical and organizational psychology have explored psychological flexibility, research on psychological flexibility in leadership has not evolved much. The ability to be connected with internal experiences as opposed to controlling or avoiding them has been proposed to be an important aspect of effective leadership (Good et al., 2016; Moran, 2011). Scholars also argued that psychological flexibility is an essential component of good leadership and may improve the quality of interpersonal relationships and organizational outcomes, while habitual avoidance of one’s unpleasant internal experiences has been proposed to contribute to ineffective leadership (Ennis et al., 2015; Moran, 2011; Reb et al., 2014),

When leaders are preoccupied with controlling their upsetting internal experiences, they might not be able to focus on the present moment or on their relationships with the people around them. By contrast, if individuals do not continuously attempt to control their internal experiences, they should be better at responding to situations because their attentional focus is not impeded (Bond & Flaxman, 2006; Lloyd et al., 2013). In addition, too much EA should narrow the leader’s ability to take action because they may be distracted by trying to avoid their experiences. By contrast, individuals who are psychologically flexible (i.e., low on EA) should have more energy to deal with job demands and engage in problem-solving (Bond et al., 2006). Willingness to experience, as opposed to EA, can thus help leaders be attentive and maintain good relationships with their followers, consequently facilitating followers’ well-being and job satisfaction. However, no study has directly explored the specific effects of leaders’ EA on followers.

There are some studies that examined how leaders’ emotion regulation and emotional intelligence are linked to a variety of employee outcomes. However, the findings are inconsistent. Whereas some studies have shown that managers’ emotional intelligence is positively associated with employees’ job satisfaction (e.g., Sy et al., 2006), others have found that leaders’ emotional intelligence is not significantly related to followers’ well-being (Donaldson-Feilder & Bond, 2004). In addition, there is evidence that leaders’ use of emotion and emotion recognition are positively related to followers’ ratings of leaders’ effectiveness (Kerr et al., 2006) as well as followers’ work attitudes and emotionality (Kafetsios et al., 2011), but another study found that leaders’ emotion regulation was associated with low job satisfaction in followers (Kafetsios et al., 2011). Finally, although one study found that suppression negatively affected the quality of leader-follower relationships and was related to physical health complaints in both groups (Glasø & Einarsen, 2008), another showed that leaders’ suppression was positively related to followers’ positive affect (Kafetsios et al., 2012). Considering inconsistencies in the literature and the fact that EA is a more general construct that is only moderately related to emotion suppression, the role of leaders’ EA in followers’ well-being has yet to be explored.

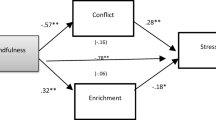

The mindfulness literature has also provided support for the roles of willingness and acceptance regarding internal experiences in leadership and followers’ well-being (e.g., Good et al., 2016; Reb et al., 2014; 2015). Mindfulness is the open, nonjudgmental awareness of one’s current experience and is aligned with the propositions of ACT and psychological flexibility (Baer, 2003; Hayes et al., 2004a). Studies have found that leaders’ mindfulness is positively associated with followers’ well-being, job satisfaction, performance, and leader-member exchange quality and negatively related to followers’ emotional exhaustion (Arendt et al., 2019; Reb et al., 2014). Researchers have argued that mindfulness provides leaders with the space to better deal with the demands of leadership (e.g., Sauer & Kohls, 2010), which is consistent with research on EA that stresses the negative consequences of habitually avoiding internal experiences and failing to pursue value-driven actions (Hayes et al., 2006; Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000).

There are also findings from research on the role of EA in interpersonal relationships in general. For instance, in research on romantic couples, Twiselton et al. (2020) found that an individual’s psychological flexibility predicted their partner’s relationship quality ratings. In a study of veterans and their partners, Zamir et al. (2018) found that a person’s own EA was negatively related to their partner’s relationship quality ratings. Similarly, Reddy et al. (2011) showed that the higher an individual’s EA, the lower the partner’s relationship adjustment. Such findings have the potential to translate into workplace relationships, such as leader-follower relationships. To our knowledge, however, interpersonal aspects of EA have not been studied in organizational settings.

The role of psychological need satisfaction and frustration

In this study, we proposed a mechanism by which leaders’ EA is linked with followers’ well-being: basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration. According to self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), the key ingredient for well-being is the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Various studies have documented that need satisfaction facilitates motivation, optimal functioning, well-being, and individual growth (e.g., Reis et al., 2000; Şimşek & Koydemir, 2013; Sheldon & Bettencourt, 2002). Satisfaction of psychological needs is also associated with performance at work, job satisfaction, and employee well-being (Baard et al., 2004; Gomez-Baya & Lucia-Casademunt, 2018). Need frustration (i.e., the extent to which psychological needs are thwarted) on the other hand, is associated with a variety of ill-being outcomes, including anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, and negative affect (Bartholomew et al., 2011; Campbell et al., 2018; Serhatoğlu et al., 2022). It is also related to higher stress and lower work engagement (Olafsen et al., 2021; Trépanier et al., 2015).

Studies in leadership found that followers’ psychological need satisfaction mediated the effects of leaders’ mindfulness on followers’ performance (Reb et al., 2014) and both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (Chang et al., 2014). Followers’ psychological need satisfaction was also found to mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and job satisfaction (Kovjanic et al., 2012).

On the basis of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature, we propose that as leaders practice EA, they will be less likely to have the resources to provide a context in which their employees’ psychological needs can be met and that these needs may be thwarted. We hypothesize that EA will be negatively linked to followers’ well-being outcomes, namely, subjective happiness, purpose in life, and job satisfaction, via its negative association with need satisfaction and its positive association with need frustration. Thus, we specifically hypothesize that basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration will mediate the relationship between leaders’ EA and followers’ well-being.

Method

Participants and procedure

We collected data from individuals in a leadership role in Turkey and two people who reported directly to them (followers). To participate in this study, leaders had to play a managerial/supervisory role in which they had at least three direct reports. A total of 74 leaders (34 women, 40 men) and 148 followers (83 women, 65 men) completed the questionnaires. They represented a variety of sectors, such as education, finance, health, technology, and engineering. Supervisors’ ages ranged from 18 to 65 with a mean of 42.47 (SD = 9.13), and followers’ ages ranged from 18 to 54 with a mean of 33.96 (SD = 7.89). Leaders had an average of 7 years (SD = 7.02) and followers had an average of 5 years (SD = 4.71) of experience in their current roles. A total of 5.4% of leaders had a high school degree, 46% had a bachelor’s degree, and 49% had a graduate degree or higher; 57% of followers had a bachelor’s degree, and 43% had a graduate degree or higher.

The data were collected online. We used snowball sampling, social media platforms, and personal contacts to recruit participants. We distributed the survey links to various social media platforms and personal contacts. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Bamberg. We obtained informed consent from all participants. Completing all the measures took approximately 15 min for both leaders and followers. Leaders were given the opportunity to either join a lottery with a monetary reward or receive a personality and life satisfaction assessment report based on their responses to the study measures, whereas each follower was given an Amazon gift card.

To ensure an unbiased choice of subordinates, we asked leaders to name the two subordinates whose last names came first in the alphabet and to provide their contact information. Each supervisor and their subordinates received an email that included the link to the online survey with a predetermined private code. Each triad had a group code that enabled us to match the responses. Data were provided to the researchers in a de-identified form to ensure confidentiality.

Measures

Brief experiential avoidance scale

Leaders’ EA was measured with the Brief Experiential Avoidance Scale (BEAQ; Gámez et al., 2014). The scale is a short version of the 62-item Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire (MEAQ). The BEAQ assesses a lack of willingness to experience one’s feelings, thoughts, and sensations in combination with a lack of attempts to change them. A sample item is, “One of my big goals is to be free from painful emotions.” The BEAQ has 15 items that are rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). The scale has good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.80 to 0.89 in previous studies (Gámez et al., 2014; Vázquez-Morejón et al., 2019). We translated the scale into Turkish using a back-translation process. Internal consistency was found to be 0.79 for the current data.

Subjective happiness scale

We measured the hedonic happiness of both leaders and followers with the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999), which is a four-item self-report instrument rated on a 7-point Likert scale. A sample item is, “Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself to be…” (ratings ranged from 1 = not a very happy person to 7 = a very happy person). The SHS has good reliability and convergent validity (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999). We used the Turkish adaptation of the SHS by Doğan and Totan (2013). For the current sample, the reliability was 0.70.

Brief purpose in life

We measured followers’ level of purpose in life using the Brief Purpose in Life (BPIL; Hill et al., 2015) scale, which is a four-item self-report measure rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The BPIL measures the themes of goal setting and sense of direction in life. Sample items are, “There is a direction in my life” and “I know which direction I am going to follow in my life.” Previous studies reported good reliability (e.g., 0.87; Hill et al., 2015). We translated the scale into Turkish using a back-translation process. Internal consistency was 0.83 for the current data.

Brief job satisfaction measure II

We used the Brief Job Satisfaction Measure II (BJSM-II; Judge et al., 1998) to measure followers’ job satisfaction. The BJSM-II is a five-item self-report instrument with a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). A sample item is, “Each day of work seems like it will never end.” The scale had a reliability of 0.88 in previous research (Judge et al., 1998). We translated it into Turkish using a back-translation process. Internal consistency was 0.70 in the current sample.

Basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration scale

We measured followers’ need satisfaction and frustration with the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (Chen et al., 2014). This scale consists of 24 items measuring autonomy satisfaction (e.g., “I feel a sense of choice and freedom in the things I undertake”), autonomy frustration (e.g., “Most of the things I do feel like ‘I have to’”), relatedness satisfaction (e.g., “I feel that the people I care about also care about me”), relatedness frustration (e.g., “I feel excluded from the group I want to belong to”), competence satisfaction (e.g., “I feel confident that I can do things well”), and competence frustration (e.g., “I have serious doubts about whether I can do things well”) rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (completely true). The Turkish adaptation of the scale by Serhatoğlu et al. (2019) was used in the current study. Because we were interested in the general level of frustration of needs, we used the total scores for both need satisfaction and frustration. In the current sample, the internal consistency was 0.85 for need satisfaction and 0.79 for need frustration.

Results

Descriptive statistics were computed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25 (IBM Corp., 2017). The hypotheses were tested using Mplus, version 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

As we collected data from two followers per leader, our data had a hierarchical and nonindependent structure. Thus, followers’ evaluations on Level 1 were nested in leaders’ evaluations of their own EA on Level 2. The Level 2 predictor, leaders’ EA, was centered on the grand mean prior to analyses.

To test the hypothesized indirect effects, we analyzed two separate multilevel mediation models described by Preacher et al. (2010, 2011). We included leaders’ EA as the predictor on Level 2, followers’ psychological need satisfaction (Model 1) and need frustration (Model 2) as the mediators on Level 1, and followers’ subjective happiness, job satisfaction, and purpose in life as outcomes on Level 1 (see MPlus syntax in the supplementary material). Thus, we had a 2-1-1 model (leader-level predictor, follower-level mediators, follower-level outcomes). In the null model, we first checked the intraclass correlation, which is defined as the ratio of between-group variance to total variance (ICC (1); Bryk & Raudenbush, 1988) and which measures the degree of dependence within a cluster (i.e., followers pertaining to one leader), was 0.20 for psychological need satisfaction, 0.12 for psychological need frustration, 0.13 for subjective happiness, 0.37 for job satisfaction, and 0.10 for purpose in life, indicating that multilevel modeling was appropriateFootnote 1. Model fit was acceptable to good with RMSEA = 0.08 for Model 1 and 0.00 for Model 2, CFI = 0.99 for Model 1 and 1.00 for Model 2, and TLI = 0.93 for Model 1 and 1.07 for Model 2, and SRMR = 0.05/0.12 (within/between) for Model 1 and 0.03/0.10 (within/between) for Model 2 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

In Model 1, leaders’ EA did not predict followers’ psychological need satisfaction (b = − 0.09, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [-0.21, 0.03], p = .126). Thus, even though need satisfaction predicted all follower outcomes (see Table 2), the hypothesized indirect effects were not significant (all ps > 0.129). In Model 2, leaders’ EA predicted followers’ psychological need frustration (b = 0.14, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.03, 0.26], p = .014). Furthermore, need frustration predicted all follower outcomes (see Table 2). The indirect effects of leaders’ EA on followers’ subjective happiness (b = − 0.11, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [-0.21, − 0.01], p = .026), job satisfaction (b = − 0.10, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [-0.18, − 0.01], p = .026), and purpose in life (b = − 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [-0.14, − 0.01], p = .025) via psychological need frustration were all significantFootnote 2.

Discussion

We aimed to apply ACT’s propositions regarding the association of EA with well-being to leader-follower relationships and empirically test the extent to which leaders’ EA was associated with their followers’ well-being and whether that relationship was mediated by followers’ psychological need satisfaction and frustration. The findings showed that need frustration mediated the link between leaders’ EA and followers’ well-being, whereas need satisfaction did not.

We specifically found that the higher the EA of leaders, the higher their followers’ need frustration, which in turn was negatively associated with all well-being outcomes, namely, subjective well-being, purpose in life, and job satisfaction. On the other hand, leaders’ EA was not a significant predictor of followers’ need satisfaction, and therefore, our hypothesis regarding the mediating effect of psychological need satisfaction was not supported, although need satisfaction significantly predicted all the well-being outcomes.

Although the role of EA in employees’ well-being and ill-being has been studied extensively over the last few decades (Hayes, Follette & Linehan, 2004; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Machell et al., 2015), the focus of previous research has often been clinical and mainly on the intraindividual level. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that leaders’ EA—the tendency to negatively evaluate unwanted internal experiences, remain disconnected from them, and refrain from expressing them—is linked to their followers’ well-being. There is evidence that leaders’ mindfulness—an aspect of psychological flexibility (e.g., Chang et al., 2014; Reb et al., 2014)—and their emotion regulation (e.g., Kafetsios et al., 2011; Sy et al., 2006) are related to followers’ well-being outcomes. Our findings add to this literature in providing evidence for the relevance of EA as a broader concept in leader-follower triads. They extend previous research by providing preliminary evidence of the link between leaders’ problematic tendencies in dealing with their internal experiences and the well-being of their followers (see Gooty et al., 2010; Rajah et al., 2011).

In line with the propositions of self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), we also showed that psychological need satisfaction was positively associated and need frustration was negatively associated with followers’ well-being, findings that are consistent with previous research (Baard et al., 2004; Fernet et al., 2013; Olafsen et al., 2021). More importantly, our findings showed that psychological need frustration explained the effect of leaders’ EA on followers’ well-being. In other words, it appears that the ways in which leaders approach their own unwanted internal experiences make them behave in a manner that drains their followers’ psychological energy through the frustration of the basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness and thus undermines followers’ well-being. The fact that EA did not predict need satisfaction might be explained by the distinct nature of need satisfaction and need frustration. Although in its earlier conceptualization, need frustration was regarded as the absence of need satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan, 1995), there is considerable evidence that a high score on need frustration is a stronger predictor of negative experiences than a low score on need satisfaction is, and need satisfaction is a better predictor of well-being than need frustration is (Bartholomew et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2014; Rouse et al., 2020). A meta-analysis on need satisfaction in the workplace also showed that need satisfaction was more closely related to positive outcomes than it was to negative outcomes (Van den Broeck et al., 2016). Our findings are also consistent with previous research that showed that suppression of emotions was more strongly associated with need frustration than it was with need satisfaction (Benita et al., 2019). However, more research with different samples is needed to compare how EA is associated with need satisfaction versus need frustration.

Habitual EA consumes attention and energy as the individual is preoccupied with controlling their internal experiences, such as emotions and thoughts, which could amplify negative emotions and thus promote ill-being (Hayes, Strosahl et al., 2004, 2006). This idea is aligned with findings on the paradoxical effect of thought suppression (Wegner et al., 1987) and might explain why leaders’ EA is associated with the frustration of their followers’ needs. Leaders might not have enough resources to pay attention to what their followers need. The less individuals attempt to control their internal experiences, the better they can respond to situational demands (Lloyd et al., 2013). In addition, as people accept their emotions and thoughts, they respond more flexibly and are better able to deal with the demands of their daily work (Sauer & Kohls, 2010; Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000). There is longitudinal evidence from the workplace that higher acceptance of personal experiences predicts mental health and performance over a year (Bond & Bunce, 2003). There is also evidence that deliberate efforts to align felt emotions with emotional displays in the form of controlled affect regulation contributes to emotional exhaustion (Biron & Van Veldhoven, 2012), which can in turn result in leaders responding in ways that frustrate the psychological needs of their followers. However, these assumptions should be tested in future studies.

Although there is some empirical evidence that EA impairs different aspects of interpersonal relationships (e.g., Reddy et al., 2011; Zamir et al., 2018), to our knowledge, our study is the first to specifically explore the interpersonal aspects of EA in an organizational setting. The findings are consistent with the assumptions that avoidance of conflict and inner experiences negatively influence interpersonal relationships by weakening effective communication, inhibiting closeness, stimulating negative affect, and diminishing support (Gable & Impett, 2012; Gottman, 1994; Gross & John, 2003) as well as with research that documented that acceptance-based interventions such as ACT (Dahl et al., 2014; McKay et al., 2012) are effective in helping people in close relationships enhance their communication and satisfaction.

Our findings are also in line with previous studies that have shown that the extent to which leaders perceive, use, and express their emotions has an effect on their followers. For example, how leaders use their emotions affects their subordinates’ affectivity and job satisfaction (Kafetsios et al., 2011), and if leaders are exhausted, their followers suffer (Köppe et al., 2018). The way leaders express their emotions has also been found to contribute to subordinates’ mood (Kerr et al., 2006; Sy et al., 2006). Although our study focused specifically on leaders’ lack of willingness to experience unwanted inner experiences, it provides further evidence that being open to one’s emotions and thoughts, and flexibility around such experiences are an important aspect of leadership. In addition, our findings are consistent with some of the leadership theories, such as transformational leadership (Gardner & Avolio, 1998) and the interactionist-communicative approach (Riggio & Reichard, 2008).

However, it should be noted that the mediation model turned nonsignificant after we reran the analyses with leaders’ age and gender as control variables as suggested by one of the reviewers of an earlier version of our manuscript. Therefore, the results of the mediation analyses should be interpreted with caution. Leaders’ demographic attributes (e.g., age and gender) are known to be relevant to leadership effectiveness and followers’ perceptions of leaders (Paustian-Underdahl et al., 2014; Vecchio & Bullis, 2001). Future research on leaders’ EA should consider such attributes by using larger samples.

Although we used a triadic data structure, which enabled us to test our assumptions from two perspectives, the study has some limitations. First, our study utilized a correlational design, which does not allow for causal conclusions. It is important for future studies to examine the hypothesized model using a longitudinal design where the changes in leaders’ EA and followers’ well-being are measured over time. Additionally, researchers could attempt to experimentally manipulate EA to establish causal relationships. Second, our study relied on self-reports. Future research might supplement this perspective with other measurement approaches, such as informant reports and behavioral measures. Third, the current study was based on a nonrandom selection of leaders as respondents, which might affect the generalizability of the findings. Besides, we asked leaders to choose their followers on the basis of the position of their surnames in the alphabet to decrease bias through deliberate selection. However, we cannot be sure whether leaders still invited followers from whom they expected favorable ratings. Fourth, we used a single operational measure of EA. Other studies should consider additional measures of EA. Future research might also directly examine the differential effects of EA and related concepts, such as emotion regulation, emotional intelligence, and mindfulness. Fifth, the sample was drawn from Turkey, which has long been considered a relatively collectivistic culture where interdependence is high among people (Karakitapoğlu-Aygün, 2004). Studies have also found differences in well-being between samples from Turkey and Germany (e.g., Koydemir & Schütz, 2012). Caution is needed in generalizing the findings. And finally, although we used multiple measures of well-being (i.e., subjective happiness, job satisfaction, and purpose in life), there are other indicators of well-being, such as physical and interpersonal well-being. Our findings should be interpreted with respect to this limitation, and future research should include other well-being measures to capture a more complete picture.

It should also be noted that followership models have proposed that too much focus on leaders and leadership skills might draw an incomplete picture and ignore the possibility that synergetic relationships from effective followers are as important as effective leaders in determining individual and organizational well-being (Chaleff, 2009; Kellerman, 2008). Although leaders are significant in the sense that they are the ones who are providing the necessary resources and environment for their followers to flourish, each party’s contribution and the interaction between them are important (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). Future research will benefit from exploring more follower-focused data.

One of the implications of our study is that interventions that target the development of leaders’ psychological flexibility might indirectly improve followers’ well-being. We focused on only one specific aspect of psychological flexibility—EA—but this aspect is the most important and extensively studied component of psychological flexibility. Previous research has shown that interventions that are aimed at helping individuals become more flexible in approaching their internal states in the context of work (e.g., through methods such as Acceptance and Commitment Training) have resulted in an increased ability to handle work strain and reductions in burnout (Bond & Bunce, 2003; Hayes et al., 2006). Organizations might consider implementing such training programs to help leaders develop a more flexible approach to their internal experiences.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, the current study provided preliminary evidence for the association between leaders’ EA and their followers’ well-being. We also showed a possible mechanism for these relationships, namely, the frustration of basic psychological needs. The findings suggest that a rigid attitude toward one’s internal experiences as a leader might be a risk factor for followers’ well-being because it can frustrate followers’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. It seems important that leaders develop a more flexible approach to their own emotions and thoughts to become attentive to their own needs and those of their followers. Organizational efforts to increase flexibility related to negative experiences may constitute an important opportunity to sustain well-being among both leaders and their followers.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in OSF storage with the identifier https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/G796P.

Notes

We additionally calculated the ICC (2), which is an estimate of the reliability of the group means (Bliese, 2000). The ICC (2) was 0.95 for psychological need satisfaction, 0.91 for psychological need frustration, 0.92 for subjective happiness, 0.98 for job satisfaction, and 0.89 for purpose in life.

In response to a reviewer’s comment, we additionally ran our analyses while controlling for leaders’ gender and age. Model fit worsened after the control variables were added with RMSEA = 0.12 for Model 1 and 0.09 for Model 2, CFI = 0.95 for Model 1 and 0.96 for Model 2, and TLI = 0.75 for Model 1 and 0.79 for Model 2, and SRMR = 0.07/0.21 (within/between) for Model 1 and 0.02/0.13 (within/between) for Model 2. In Model 1, leaders’ EA did not predict followers’ psychological need satisfaction (b = -0.05, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [-0.17, 0.08], p = .473). Thus, even though need satisfaction predicted all follower outcomes, the hypothesized indirect effects were not significant (all ps > 0.47). In Model 2, leaders’ EA marginally significantly predicted followers’ psychological need frustration (b = 0.10, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.02, 0.22], p = .089). Furthermore, need frustration predicted all follower outcomes. The indirect effects of leaders’ EA on followers’ subjective happiness (b = -0.07, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [-0.16, 0.02], p = .107), job satisfaction (b = -0.07, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [-0.15, 0.01], p = .107), and purpose in life (b = -0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [-0.11, 0.01], p = .106) via psychological need frustration were not significant. The full results can be obtained from the authors.

References

Arendt, J. F., Verdorfer, P., A., & Kugler, K. G. (2019). Mindfulness and leadership: Communication as a behavioral correlate of leader mindfulness and its effect on follower satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00667

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: a motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690.x

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

Bakker, A. B., Hetland, J., Kjellevold Olsen, O., & Espevik, R. (2022). Daily transformational leadership: A source of inspiration for follower performance?European Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2022.04.004

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., Bosch, J. A., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2011). Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(11), 1459–1473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211413125

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership. Psychology Press.

Benita, M., Benish-Weisman, M., Matos, L., & Torres, C. (2019). Integrative and suppressive emotion regulation differentially predict well-being through basic need satisfaction and frustration: A test of three countries. Motivation and Emotion, 44(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09781-x

Biron, M., & van Veldhoven, M. (2012). Emotional labour in service work: Psychological flexibility and emotion regulation. Human Relations, 65(10), 1259–1282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712447832

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein, & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

Bond, F. W., & Bunce, D. (2000). Mediators of change in emotion-focused and problem-focused worksite stress management interventions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.156

Bond, F. W., & Bunce, D. (2003). The role of acceptance and job control in mental health, job satisfaction, and work performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 1057. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1057

Bond, F. W., & Flaxman, P. E. (2006). The ability of psychological flexibility and job control to predict learning, job performance, and mental health. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 26(1–2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v26n01_05

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2006). Psychological flexibility, ACT, and organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 26(1–2), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v26n01_02

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., & Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

Bond, F. W., Lloyd, J., & Guenole, N. (2013). The work-related acceptance and action questionnaire: Initial psychometric findings and their implications for measuring psychological flexibility in specific contexts. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(3), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12001

Bond, F. W., & Donaldso-Feilder, E. J. (2004). The relative importance of psychological acceptance and emotional intelligence to workplace well-being. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 32(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/08069880410001692210

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1988). Toward a more appropriate conceptualization of research on school effects: A three-level hierarchical linear model. American Journal of Education, 97(1), 65–108. https://doi.org/10.1086/443913

Campbell, R., Boone, L., Vansteenkiste, M., & Soenens, B. (2018). Psychological need frustration as a transdiagnostic process in associations of self-critical perfectionism with depressive symptoms and eating pathology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(10), 1775–1790. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22628

Chaleff, I. (2009). The courageous follower. San Francisco, CA: Barrett-Koehler.

Chang, J., Huang, C., & Lin, Y. (2014). Mindfulness, basic psychological needs fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(5), 1149–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9551-2

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2014). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Dahl, J., Stewart, I., Martell, C. R., & Kaplan, J. S. (2014). ACT and RFT in relationships: Helping clients deepen intimacy and maintain healthy commitments using acceptance and commitment therapy and relational frame theory. New Harbinger Publications.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Doğan, T., & Totan, T. (2013). Psychometric properties of Turkish version of the Subjective Happiness Scale. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being, 1(1), 21–28.

Donaldson-Feilder, E. J., & Bond, F. W. (2004). The relative importance of psychological acceptance and emotional intelligence to workplace well-being. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 32(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/08069880410001692210

Ennis, G., Happell, B., & Reid-Searl, K. (2015). Clinical leadership in mental health nursing: The importance of a calm and confident approach. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 51(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12070

Fernet, C., Austin, S., Trépanier, S. G., & Dussault, M. (2013). How do job characteristics contribute to burnout? Exploring the distinct mediating roles of perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2011.632161

Gable, S. L., & Impett, E. A. (2012). Approach and avoidance motives and close relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00405.x

Gámez, W., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., Ruggero, C., Suzuki, N., & Watson, D. (2014). The Brief Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire: Development and initial validation. Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034473

Gardner, W. L., & Avolio, B. J. (1998). The charismatic relationship: A dramaturgical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 32–58. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.192958

Gerhart, J. I., Baker, C. N., Hoerger, M., & Ronan, G. F. (2014). Experiential avoidance and interpersonal problems: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3(4), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.08.003

Glasø, L., & Einarsen, S. (2008). Emotion regulation in leader-follower relationships. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17(4), 482–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320801994960

Gomez-Baya, D., & Lucia‐Casademunt, A. M. (2018). A self‐determination theory approach to health and well‐being in the workplace: Results from the sixth European working conditions survey in Spain. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(5), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12511

Good, D. J., Lyddy, C. J., Glomb, T. M., Bono, J. E., Brown, K. W., Duffy, M. K., et al. (2016). Contemplating mindfulness at work: An integrative review. Journal of Management, 42, 114–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315617003

Gooty, J., Connelly, S., Griffith, J., & Gupta, A. (2010). Leadership, affect and emotions: A state of the science review. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 979–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.005

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce. Hillsdale: NJ; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Hayes, S. C., Follette, V. M., & Linehan, M. (Eds.). (2004). Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., Wilson, K. G., Bissett, R. T., Pistorello, J., Toarmino, D., & McCurry, S. M. (2004). Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record, 54(4), 553–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03395492

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd edition). Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(6), 1152. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152

Hill, P. L., Edmonds, G. W., Peterson, M., Luyckx, K., & Andrews, J. A. (2015). Purpose in life in emerging adulthood: Development and validation of a new brief measure. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1048817

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Humphrey, R. H. (2002). The many faces of emotional leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(5), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00140-6

Humphrey, R. H. (2012). How do leaders use emotional labor? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(5), 740–744. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1791

Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., & Hawver, T. (2008). Leading with emotional labor. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810850790

Corp, I. B. M. (Released 2017). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1301–1334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x

Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., Durham, C. C., & Kluger, A. N. (1998). Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.17

Kafetsios, K., Nezlek, J. B., & Vassiou, A. (2011). A multilevel analysis of relationships between leaders’ and subordinates’ emotional intelligence and emotional outcomes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(5), 1121–1144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00750.x

Kafetsios, K., Nezlek, J. B., & Vassilakou, T. (2012). Relationships between leaders’ and subordinates’ emotion regulation and satisfaction and affect at work. The Journal of Social Psychology, 152(4), 436–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2011.632788

Karakitapoğlu-Aygün, Z. (2004). Self, identity and well- being among Turkish university students. Journal of Psychology, 138, 457–478. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.138.5.457-480

Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001

Kashdan, T. B., Barrios, V., Forsyth, J. P., & Steger, M. F. (2006). Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(9), 1301–1320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.003

Kellerman, B. (2008). Followership. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Kerr, R., Garvin, J., Heaton, N., & Boyle, E. (2006). Emotional intelligence and leadership effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27, 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730610666028

Koydemir, S., & Schütz, A. (2012). Emotional intelligence predicts components of subjective well-being beyond personality: A two-country study using self- and informant reports. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.647050

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., Jonas, K., Quaquebeke, N. V., & Van Dick, R. (2012). How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of employees’ needs as mediating links. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1031–1052. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1771

Köppe, C., Kammerhoff, J., & Schütz, A. (2018). Leader-follower crossover: Exhaustion predicts somatic complaints via StaffCare behavior. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(3), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-10-2017-0367

Lloyd, J., Bond, F. W., & Flaxman, P. E. (2013). The value of psychological flexibility: Examining psychological mechanisms underpinning a cognitive behavioural therapy intervention for burnout. Work & Stress, 27(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2013.782157

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155.

Machell, K. A., Goodman, F. R., & Kashdan, T. B. (2015). Experiential avoidance and well-being: A daily diary analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 29(2), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.911143

McKay, M., Lev, A., & Skeen, M. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy for interpersonal problems: Using mindfulness, acceptance, and schema awareness to change interpersonal behaviors. New Harbinger Publications.

Moran, D. J. (2011). ACT for leadership: Using acceptance and commitment training to develop crisis-resilient change managers. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 7(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100928

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (1998–2012) (p. 6). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Olafsenö, A. H., Niemic, C. P., Deci, E. L., Halvari, H., Nilsen, E. R., & Williams, G. C. (2021). Mindfulness buffers the adverse impact of need frustration on employee outcomes: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts5.93

Onwezen, M. C., van Veldhoven, M. J. P. M., & Biron, M. (2014). The role of psychological flexibility in the demands–exhaustion–performance relationship. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.742242

Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., Walker, L. S., & Woehr, D. J. (2014). Gender and perceptions of leadership effectiveness: A meta-analysis of contextual moderators. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 1129–1145.

Pomerantz, E. M., Saxon, J. L., & Oishi, S. (2000). The psychological trade-offs of goal investment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 617. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.617

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework forassessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141

Preacher, K. J., Zhang, Z., & Zyphur, M. J. (2011). Alternative methods for assessing mediation in multilevel data: The advantages of multilevel SEM. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 18(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2011.557329

Purdon, C. (1999). Thought suppression and psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37(11), 1029–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00200-9

Rajah, R., Song, Z., & Arvey, R. D. (2011). Emotionality and leadership: Taking stock of the past decade of research. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1107–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.09.006

Reb, J., Narayanan, J., & Chaturvedi, S. (2014). Leading mindfully: Two studies on the influence of supervisor trait mindfulness on employee well-being and performance. Mindfulness, 5(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0144-z

Reb, J., Narayanan, J., & Ho, Z. W. (2015). Mindfulness at work: Antecedents and consequences of employee awareness and absent-mindedness. Mindfulness, 6(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0236-4

Reddy, M. K., Meis, L. A., Erbes, C. R., Polusny, M. A., & Compton, J. S. (2011). Associations among experiential avoidance, couple adjustment, and interpersonal aggression in returning Iraqi war veterans and their partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 515–520. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023929

Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200266002

Riggio, R. E., & Reichard, R. J. (2008). The emotional and social intelligences of effective leadership: An emotional and social skill approach. Journal of Managerial Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810850808

Rouse, P. C., Turner, P. J., Siddall, A. G., Schmid, J., Standage, M., & Bilzon, J. L. (2020). The interplay between psychological need satisfaction and psychological need frustration within a work context: A variable and person-oriented approach. Motivation and Emotion, 44(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09816-3

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality, 63(3), 397–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sauer, S., & Kohls, N. (2010). Mindfulness in leadership: Does being mindful enhance leaders’ business success? On Thinking, 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-15423-2_17

Serhatoğlu, S., Şimsek, O. F., Ulusoy, B., & Koydemir, S. (2019). Big Five personality traits, well-being and ill-being: The mediating roles of basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration. 7th International Self-Determination Theory Conference, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Serhatoğlu, S., Koydemir, S., & Schütz, A. (2022) When mindfulness becomes a mental health risk: The relevance of emotion regulation difficulties and need frustration. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2022.2048777

Sheldon, K. M., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2002). Psychological need-satisfaction and subjective well-being within social groups. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466602165036

Şimşek, Ö. F., & Koydemir, S. (2013). Linking metatraits of the Big Five to well-being and ill-being: Do basic psychological needs matter? Social Indicators Research, 112(1), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0049-1

Stanton, K., & Watson, D. (2014). Positive and negative affective dysfunction in psychopathology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(9), 555–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12132

Sy, T., Tram, S., & O’hara, L. A. (2006). Relation of employee and manager emotional intelligence to job satisfaction and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.10.003

Trépanier, S. G., Forest, J., Fernet, C., & Austin, S. (2015). On the psychological and motivational processes linking job characteristics to employee functioning: Insights from self-determination theory. Work & Stress, 29(3), 286–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1074957

Tull, M. T., Gratz, K. L., Salters, K., & Roemer, L. (2004). The role of experiential avoidance in posttraumatic stress symptoms and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatization. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(11), 754–761. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000144694.30121.89

Twiselton, K., Stanton, S. C., Gillanders, D., & Bottomley, E. (2020). Exploring the links between psychological flexibility, individual well-being, and relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 27(4), 880–906. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12344

Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.007

Van den Broeck, A., Ferris, D. L., Chang, C., & Rosen, C. C. (2016). A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1195–1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316632058

Vázquez-Morejón, R., Rubio, J. M., Rodríguez, A. M., & Vázquez Morejón, A. J. (2019). Brief experiential avoidance questionnaire - Spanish version. PsycTESTS Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/t77599-000

Vecchio, R. P., & Bullis, R. C. (2001). Moderators of the influence of supervisor-subordinate similarity on subordinate outcomes. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2001(1), B1-B6. https://doi.org/10.5465/apbpp.2001.6133112

Wegner, D. M., Schneider, D. J., Carter, S. R., & White, T. L. (1987). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.1.5

Wenzlaff, R. M., & Wegner, D. M. (2000). Thought suppression. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 59–91. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.59

Wilson, K. G., & Murrell, A. R. (2004). Values work in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Setting a course for behavioral treatment. In S. C. Hayes, V. M. Follette, & M. M. Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition (pp. 120–151). Guilford Press.

Woodruff, S. C., Glass, C. R., Arnkoff, D. B., Crowley, K. J., Hindman, R. K., & Hirschhorn, E. W. (2014). Comparing self-compassion, mindfulness, and psychological inflexibility as predictors of psychological health. Mindfulness, 5(4), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0195-9

Zamir, O., Gewirtz, A. H., Labella, M., DeGarmo, D. S., & Snyder, J. (2018). Experiential avoidance, dyadic interaction and relationship quality in the lives of veterans and their partners. Journal of Family Issues, 39(5), 1191–1212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X17698182

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Gokce Memis and Idil Ozdemir for collecting the data and providing support. We thank Jane Zagorski for language editing.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This manuscript and its analyses have not been published in any part or capacity, and this manuscript is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Conflict of interest

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koydemir, S., Varol, M., Fehn, T. et al. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between leaders’ experiential avoidance and followers’ well-being. Curr Psychol 42, 28344–28355 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03865-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03865-7