Abstract

Aggressive collective action online has many negative impacts on the online environment and can even lead to political violence or social panic in the offline world. Although the effect of relative deprivation on aggression toward the compared object is well known, the influence of relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group has been ignored. Thus, this study attempted to explore the effect, as well as the mediating mechanism underlying it. We found that group relative deprivation manipulated by an employment problem scenario (with the triggering event as a covariable) can enhance aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group, with hostile feelings mediating the effect. These results support and develop the relative deprivation theory, frustration–aggression theory, stress and coping theory, and deepen the understanding of the relationship between relative deprivation and aggression. The findings also suggest that colleges should focus more on graduate employment problems and decreasing the relative deprivation experienced by undergraduate students in efforts to prevent aggressive collective action online.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Collective action refers to any action taken by members of a group to improve the conditions of that group as a whole (van Zomeren & Iyer, 2009; van Zomeren et al., 2012). Collective action can be either nonaggressive (e.g., petitions, peaceful demonstrations) or aggressive (e.g., riots, violent demonstrations) (Besta et al., 2019; Saab et al., 2016). Aggressive collective action has negative impacts on both public health and social order (Saab et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2012). For example, it can cause severe physical harm, political violence, and public panic (Saab et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2012). In recent years, social media and the broader Internet have provided a new environment for aggressive forms of collective action, referred to as aggressive collective action online (Besta et al., 2019; Spears & Postmes, 2015; Wilkins et al., 2019). This type of action occurs when group members hurt others or damage property through electronic communications (e.g., forum posts, social media posts, emails, or messages in online chat rooms) to improve their group’s conditions (Moore et al., 2012; Saab et al., 2016; Song et al., 2018). This can take a variety of forms, including using crude language, spreading rumors, engaging in smearing and harassing behavior (Li, 2007), posting aggressive comments (Bogolyubova et al., 2018; Moore et al., 2012), and so on. Aggressive collective action online not only impacts the order of the online environment but also impacts the offline world due to negative emotions and extremism within the public (Song et al., 2018).

Aggressive collective action online has grown rapidly in recent years due to the rising importance of the Internet. To prevent and intervene in aggressive collective action online, it is important to understand the factors that trigger it. However, only one study (Song et al., 2018) has explored the factors influencing aggressive collective action online. The factors of aggressive collective action online and the mediation path underlying this effect are not clear. Studies drawing on traditional collective action (Grant & Brown, 1995; Kosakowska-Berezecka et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2018; van Zomeren & Iyer, 2009) have suggested that collective action is caused by group relative deprivation and hostile feelings. This study further tested the relationship between group relative deprivation, hostile feelings, and aggressive collective action online in detail to better understand a subclass of aggressive collective action online and how such action is generated.

Group relative deprivation and aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group

Group relative deprivation refers to a sense of deprivation caused by comparing one’s ingroup with relatively advantaged outgroups (Meuleman et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2020; Zubielevitch et al., 2020). Relative deprivation theory suggests that people compare their ingroup with outgroups, which creates feelings of group relative deprivation when they perceive a comparative disadvantage; this, in turn, can lead to collective action (Besta et al., 2019; Smith & Huo, 2014; Smith et al., 2012; Smith, Pettigrew et al., 2020; Smith, Blackwood et al., 2020). There are several reasons for the effect of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action. First, aggressive collective action can be used to reduce people’s disadvantage and improve their conditions (Saab et al., 2016; Smith, Blackwood et al., 2020). In other words, according to stress and coping theory (Feeney & Fitzgerald, 2022; Lee et al., 2021; van Zomeren, 2021), aggressive collective action toward an outgroup provocateur could be thought of as a stress response or strategy to decrease the stress experience derived from group relative deprivation. Second, following the frustration–aggression hypothesis, frustration can lead to aggression (Berkowitz, 1989; Gilbert & Bushman, 2020). Group relative deprivation could be regarded as an experience or sense of frustration and could lead to aggressive collective action toward an outgroup provocateur (Koomen & Fränkel, 1992; Smith & Huo, 2014; Smith et al., 2020a, b; Song et al., 2018). Specifically, when individuals compare their group with outgroups and perceive comparative disadvantage, a sense of frustration arises, which could in turn trigger aggressive collective action toward the outgroup provocateur.

The Internet is a powerful communication tool that can be used to strengthen connections within disadvantaged groups, potentially enabling people to support crowd violence or aggression across time and space barriers (Spears & Postmes, 2015). Therefore, it is plausible that aggressive collective action online could be predicted by group relative deprivation. This idea is preliminarily supported by a prior study (Song et al., 2018), which found that group relative deprivation (measured in terms of a relative deprivation scale) significantly positively predicted aggressive collective action online toward an outgroup provocateur.

In summary, existing theoretical views and empirical studies (Besta et al., 2019; Saab et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2018; Song et al., 2018) have focused on the effect of group relative deprivation on aggression toward an outgroup provocateur, while ignoring whether group relative deprivation could influence aggression toward ingroup members. Additionally, the effect of group relative deprivation on other aggressive collective action online and its underlying mechanism remain unclear. First, in Song et al.’s (2018) study, aggressive collective action online was measured using a questionnaire, which could not explore the causal relationship. Hence, whether there is a causal relationship between group relative deprivation and aggressive collective action online is not clear and should be tested in an experimental research context. Second, the group relative deprivation predicted aggressive collective action online has only been examined in one study (Song et al., 2018), whose findings should be replicated. Therefore, in this study, we sought to focus on ingroup members and tested the influence of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group through manipulating group relative deprivation in terms of employment situation. The term “deprivation-related provocateurs within the group” here refers to certain members of a group who harm many other members of the same group with selfish behaviors that aggravate many ingroup members’ sense of group deprivation. “Aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group” refers to a group’s collective harmful behavior via the Internet targeting certain members of the same group who harm many other group members for their own benefit through behaviors that promote a sense of group deprivation.

The present study makes several contributions. First, our work extends the influence object of group relative deprivation from the outgroup to the ingroup, which enriches the literature on the effect of group relative deprivation. Second, the present study presents a new theoretical explanation for the relationship between relative deprivation and aggression and thus may broaden the application of frustration–aggression theory and stress and coping theory to the area of group relative deprivation and aggressive collective action online. Third, exploring aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group can expand the objects of aggressive collective action online studied in the literature to date.

We used an employment problem scenario to manipulate group relative deprivation. The validity of this scenario was verified among Chinese undergraduate students (Zhang et al., 2012). Such students attach great importance to their employment status and tend to compare themselves with students from other colleges, making them vulnerable to group relative deprivation (Zhang et al., 2012). Moreover, the undergraduate employment rate in China has an important impact on the enrollment rate and Ministry of Education funding in the following year, causing some college decision-makers to adopt inappropriate employment measures to force their graduates to sign agreements with employers before they leave college. The college decision-makers are considered the deprivation-related provocateurs within the group in this study. Because college decision-makers are in the same college as the students, they adopt inappropriate employment measures that preserve their own advantage at the cost of harming the students, which would aggravate students’ sense of group relative deprivation.

In summary, when undergraduate students compare themselves with students at other universities, the more they perceive a comparative disadvantage in terms of employment situation, the higher they will experience group relative deprivation, which is likely to trigger those students to engage in aggressive collective action online toward college decision-makers who adopt inappropriate employment measures.

Mediating role of hostile feelings

Prior research has suggested that negative affect (e.g., individual’s hostile feelings) (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2017, 2018a) mediates the relationship between personal relative deprivation and aggressive behavior. Moreover, the frustration–aggression theory suggests that there are potential mediating variables between frustration and aggression and that frustration can cause sufficient negative feelings to lead to aggression (Berkowitz, 1989; Gilbert & Bushman, 2020). The stress and coping theory suggests that stressful life event can induce psychological stress (e.g., negative emotions response) which may in turn lead to maladaptive coping activities (i.e., aggressive behavior; Lee et al., 2021). Therefore, it is plausible that hostile feelings may act as a mediator in the effect of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group. Hostile feelings are defined as negative feelings or experiences, such as distrust, anger, resentment, irritation, and disgust, toward one or more people (Musante et al., 1989), which have been found to include both negative feelings and experiences of individuals (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2017, 2018a) as well as hostile feelings toward other groups (Anier et al., 2016; Guimond & Dambrun, 2002; Halevy et al., 2010).

Group relative deprivation and hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group

Previous studies have shown that group relative deprivation can lead to negative emotions such as anger (van Zomeren et al., 2004, 2008) and resentment (Smith et al., 2012), both of which are involved in hostility (Musante et al., 1989; Smith et al., 2004). Importantly, the experience of personal relative deprivation predicts participants’ hostile feelings (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2017, 2018a, b), and group relative deprivation encourages intergroup hostile feelings (Guimond & Dambrun, 2002; Gurr, 1970). Thus, group relative deprivation can predict hostile feelings. However, these studies focused on hostile feelings toward an outgroup provocateur (Guimond & Dambrun, 2002; Gurr, 1970), neglecting hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group. “Hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group” refers to the negative feelings of a group member toward certain members of the same group who harm many other members of the group through actions undertaken for their own benefit that promote a sense of group deprivation among other ingroup members. We further suppose that the experience of group relative deprivation can increase students’ common hostile feelings toward college decision-makers who adopt inappropriate employment measures, as in the present study. This may be because that the sense of group relative deprivation is a kind of psychological stress, which makes people more sensitive to other stressful events and primes hostile feelings in response to the provoking behavior. In other words, the previous sense of group relative deprivation derived from the employment problem makes students more sensitive and irritable to the inappropriate employment measures, and the common hostile feelings of the group members triggered by the behavior of college decision-makers who adopt inappropriate employment measures is enhanced by the pre-existing sense of group relative deprivation.

Hostile feelings and aggressive collective action online towards deprivation-related provocateurs within the group

There are several reasons why stronger hostile feelings predict stronger aggressive collective action online towards deprivation-related provocateurs within the group. First, hostile feelings can lead to aggressive behavior (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2017, 2018a). Second, hostile feelings were believed to promote collective action toward an outgroup provocateur (Grant & Brown, 1995). According to Intergroup Emotions Theory, emotions shared by groups can shape group members’ desire to engage in collective action (Paterson et al., 2019; Smith, 1993). Thus, when hostile feelings spread within groups, they may lead to aggressive collective action by group members. Third, many studies have shown that the experience of anger leads to a willingness to engage in aggressive collective action (Iyer et al., 2007; Mackie et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2008; Tausch & Becker, 2013) and aggressive collective action online (Song et al., 2018). Hostile feeling refers to anger (Anderson et al., 1995; Smith et al., 2004; Strong et al., 2005). Thus, hostile feelings may drive group members to take aggressive collective action. As undergraduate students today are generally digital natives who enjoy discussing employment issues online, aggressive collective action online toward college decision-makers within the group may be relatively easy to create and incite among some students. Therefore, it is possible that hostile feelings toward college decision-makers who adopt inappropriate employment measures may motivate undergraduate students to take aggressive collective action online.

In general, group relative deprivation predicts both hostile feelings and aggressive collective action online towards deprivation-related provocateurs within the group, and hostile feelings may predict aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group. Based on the frustration–aggression theory (Berkowitz, 1989; Gilbert & Bushman, 2020) and stress and coping theory (Lee et al., 2021), we further hypothesize that group relative deprivation which is deemed to group members’ common frustration and stress could enhance the hostile feelings of group members (e.g., the undergraduate students in the present study), which are triggered by the deprivation-related behavior of certain intergroup members (e.g., college decision-makers). The enhanced hostile feelings then lead to more aggressive collective action online toward the provocateur within the group (e.g., college decision-makers who adopt inappropriate employment measures).

Overview of the present study

The present study aimed to explore the effect of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group, as well as the potential mediation of hostile feelings on the effect, under a simulated network scenario in the context of an employment survey.

The study included three hypotheses:

-

1.

Group relative deprivation could predict hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers who adopt inappropriate employment measures (the deprivation-related provocateurs within the group; Hypothesis 1).

-

2.

Group relative deprivation could also predict aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group (Hypothesis 2).

-

3.

The effect of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group should be mediated by hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group (Hypothesis 3).

Methods

Participants

A priori power analysis using the GPower software (Faul et al., 2007) to determine the minimum sample size required for this study. The median effect size was always set to f2 = 0.15 in previous studies that have used regression analysis to calculate mediating effect (Ge, 2020; Pozzoli et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018). When the median effect size was set to f2 = 0.15, α = 0.05, and 1 − β = 0.9, a minimum of 88 subjects was deemed necessary to use regression analysis with two predictors. Thus, we recruited 114 undergraduates majoring in different subjects from the host university in China. Six participants were excluded from the analysis because they guessed the purpose of the experiment. This left a final sample of 108 participants (45 male and 63 female participants, mean age = 20.89 years, SD = 1.11 years). We randomly assigned the participants to one of two groups: high group relative deprivation condition (n = 57) and low group relative deprivation condition (n = 51). All participants gave informed written consent and received payment after their participation. The study was approved by the Research Project Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the authors’ university and was performed following the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Manipulation material of group relative deprivation

In line with previous research (Guimond & Dambrun, 2002; Zhang et al., 2012), the fabricated materials used to manipulate group relative deprivation were presented as official reports dealing with the employment situation by the Chinese Ministry of Education. The report included bar charts and text that compared college’s investment to graduate employment (i.e., number of job fairs, per capita employment expenditure, and number of employment training courses and lectures) and the employment situation of graduates (i.e., overall employment rate, average monthly income, and job satisfaction after graduation) at the participants′ university to another university in a similar region and with similar comprehensive strength. In the low group relative deprivation condition, the report informed participants that compared with the students at the outgroup (i.e., at other university), students in their ingroup (i.e., at their university) were slightly worse off. In the high group relative deprivation condition, the report informed participants that the students in their ingroup had fewer college’s investment to graduate employment and bad employment situation of graduates than those in the outgroup. A figure in the report showed that students at the host university received poor job training, had few job opportunities, and lagged far behind the other similar university was used to summarize this evidence. When questioned, no participant reported suspicion about the veracity of the reports.

To test the effectiveness of the manipulation, we developed two items (e.g., “As a student at the host university, how satisfied are you about your current and future employment situation relative to students at the other university?”) to measure group relative deprivation on the basis of the measurements used by Tropp and Wright (1999). For each item, responses were coded on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). The average score meant that higher values corresponded with increased feelings of deprivation. These two items formed a reliable scale (Cronbach α = 0.76).

Triggering event

A fabricated triggering event was employed as the background context and a covariate to trigger hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group and aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group under conditions of both high and low group relative deprivation. Participants were told that their university board had recently issued a policy requiring that students find a job before graduating; otherwise, they would not be able to obtain their degrees. To illustrate this policy, the assistant principal had recently said in an interview, “Students are responsible for the unfavorable comparisons between our university and others in terms of employment. If they want to change their situation, we think they have to find jobs as soon as possible. Therefore, we have made this decision without student approval.” This material was developed on the basis of previous research (Zhang et al., 2012). Again, when questioned, no participant expressed suspicion about the veracity of the event.

Hostile feelings

The hostile feelings subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Version (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark 1999) to measure participants’ hostile feelings. We modified the emotional words (e.g., Hostile) in the PANAS-X questionnaire according to the fabricated triggering event (e.g., What extent has the new policy issued by the assistant principal made you feel hostile) on 7-point scales ranging from 1 (extremely) to 7 (not at all). The average score on this scale represented participants’ level of hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group. The internal consistency of this questionnaire was satisfactory (Cronbach α = 0.87).

Aggressive collective action online

The occurrence of aggressive collective action online was assessed by whether participants published aggressive forum posts to support their group’s cause on the microblog (a bogus website designed for the experiment in advance). Our definition of aggressive forum posts included both verbal insults or attacks (e.g., threats of violence and profanity; Bogolyubova et al., 2018; Moore et al., 2012) and negative job-relevant evaluations (e.g., incapable and incompetent; Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2017) directed at college decision-makers within the group. Previous researchers have found that evaluations with the potential to thwart a person’s personal and career goals can be considered as damaging as physical harm (Twenge et al., 2001). Participation in the aggressive collective action online was marked as 1, whereas non-participation was counted as 0. This measure was based on previous research on aggressive collective action online (Song et al., 2018) and was modified for the specific context of our experiment.

All participants read the following (the original materials were in Chinese):

Most students at our university disagree with this policy and have decided to publish aggressive forum posts online to attack college decision-makers and improve our situation. Would you like to support us against unfair policies? If so, please publish your critical posts in our forums. If you do not want to do that, you can leave this site. Your responses will remain anonymous.

Procedure

This study was conducted by students majoring in psychology. On arrival, participants were welcomed and seated separately in our laboratory. In both conditions, participants were told that the current study was a survey concerning students’ employment. Participants first provided their demographic information (e.g., gender and grade), and then presented with one of the two versions of the reports described in "manipulate material of group relative deprivation". The content of the reports corresponded with the participants’ experimental conditions. After reading the report, they were asked to complete the measurement of manipulation checks of group relative deprivation. Next, all participants read the same article that included the triggering event, then subsequently filled out the questionnaire about hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group. Finally, participants were asked to agree or decline to publish aggressive forum posts on a webpage directing the college decision-makers to support their group members.

Statistical analyses

The descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were calculated using SPSS 24.0. To check whether our experimental manipulation had been effective, we conducted an independent-sample t-test on the high and low group relative deprivation groups. Next, we used an independent-sample t-test to examine the effect of group relative deprivation on hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group, as well as two independent-sample non-parametric tests to examine the effect of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group. Then, we examined the mediation model.

In this study, aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group was a categorical variable. Thus, in line with prior studies (Iacobucci, 2012; MacKinnon et al., 2007), we firstly adopted linear and logistic regressions to calculate the estimates of a and b and their standard errors, respectively. Next, we calculated the mediated effect Zmediation= (Za= a/SE(a)) * (Zb= b/SE(b)) (Iacobucci, 2012). Finally, following MacKinnon and Cox (2012), we adopted the distribution of the product to test the significance of the mediated effect. The distribution of the product does not require normal distribution, is suitable for small sample sizes, and can provide more accurate statistical tests and confidence intervals (MacKinnon & Cox, 2012; MacKinnon et al., 2007). This method can build confidence intervals for the mediation effect via the RMediation package of R; if the confidence intervals do not include 0, this indicates a significant mediation effect (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Descriptive statistics and the correlation of all research variables are provided in Table 1.

Manipulation check

The results showed a significant difference between the high group relative deprivation group (M = 6.01, SD = 0.84) and the low group relative deprivation group (M = 4.94, SD = 0.75), t (106) = 6.94, p < .001, effect size d = 1.34. Thus, the group relative deprivation manipulation was successful.

The effects of group relative deprivation

The results of the independent sample t-test indicate that the hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group in the high group relative deprivation condition (M = 6.06, SD = 0.76) were significantly higher than the low group relative deprivation condition (M = 5.46, SD = 0.95), t (106) = 3.68, p < .001, effect size d = 0.70. In addition, the aggressive collective action online toward the within-group college decision-makers was significantly higher in the high relative deprivation group (M = 0.84, SD = 0.37) than in the low relative deprivation group (M = 0.65, SD = 0.48), U = 1170, p = .02, effect size r = 0.22.

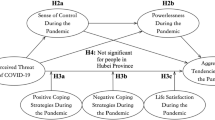

Mediation analyses

As shown in Fig. 1, group relative deprivation significantly predicted hostile feelings (β = 0.41, p < .001) and aggressive collective action online towards the college decision-makers within the group (β = 0.75, p = .004). Hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group significantly predicted aggressive collective action online (β = 0.84, p = .01) toward the college decision-makers within the group. The mediating effect of hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group in the relationship between group relative deprivation and aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group was significant (Zmediation = 12.86, 95% CI [0.12, 0.61]).

Hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group mediated the relationship between group relative deprivation and aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group. Aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group is a categorical variable, non-participation=0, participation=1

Discussion

The effectiveness of the experimental materials

This study employed a simulated scenario concerning graduate employment situation, with participants being randomly assigned to high and low group relative deprivation conditions. We found that members of the high group relative deprivation condition were significantly more dissatisfied with their employment situation than members of the low group relative deprivation condition. Moreover, the differences in the hostile feelings and aggressive collective action online towards the college decision-makers within the group between the two groups were also significant. These results indicate that the experimental materials effectively manipulated participants’ group relative deprivation. This effectiveness was consistent with the results of existing researches (Guimond & Dambrun, 2002; Zhang et al., 2012), which also shown that undergraduate students are very concerned about employment; if they find that their employment situation is not ideal, it has a negative impact on their emotions and behaviors (Guimond & Dambrun, 2002; Zhang et al., 2012).

The mediating effect of hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group

The effect of group relative deprivation on hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group

The high group relative deprivation group scored higher on hostile feelings toward the deprivation-related provocateurs within the group than the low group relative deprivation group confirm Hypothesis 1, which is in accordance with previous studies regarding group relative deprivation and hostile feelings toward the outgroup provocateur (Anier et al., 2016; Guimond & Dambrun, 2002), as well as personal relative deprivation and an individual’s hostile feelings (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2017). The present study extends these prior findings regarding group relative deprivation and hostile feelings and suggests that group relative deprivation increases the hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group. Specifically, group relative deprivation facilitated the hostile feelings of undergraduate students toward the college decision-makers within the group induced by the inappropriate decision regarding employment policies. This may be because group relative deprivation facilitates hostile interpretation and interpersonal opposition to the harming behavior, which would increase ingroup members’ sense of group relative deprivation, regardless of whether the provocateurs are ingroup or outgroup members.

The effect of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group

As mentioned above, participants in the high group relative deprivation group were more likely to engage in aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group confirm Hypothesis 2. This is consistent with a prior questionnaire survey, which found that group relative deprivation is positively associated with aggressive collective action online toward the outgroup provocateur (Song et al., 2018). The results of this study replicate and extend Song et al.’s (2018) finding that group relative deprivation can also predict another subset of aggressive collective action online (i.e., aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group).

The central factor of relative deprivation is a perception of unfair disadvantage comparison with another group; when one perceives that their ingroup is at an unfair disadvantage, feelings of group relative deprivation occur, triggering a series of behavioral responses (Smith et al., 2012), such as aggressive collective action (Smith, Blackwood et al., 2020; Xiong & Ye, 2016). Moreover, the Internet, with its anonymity, unreality, and ability to cross barriers of time and space (Spears & Postmes, 2015; Vilanova et al., 2017), provides a convenient platform for aggressive collective action by undergraduate students, who are skilled Internet users. Therefore, this study demonstrated that group relative deprivation of undergraduate students can strengthen aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group.

Hostile feelings and aggressive collective action online towards deprivation-related provocateurs within the group

In this study, hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group positively predicted aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group, which supports Hypothesis 3 and aligns with a recent study indicating that negative affect (e.g., group-based anger) predicts aggressive collective action online toward an outgroup provocateur (Song et al., 2018). This result may be explained by the fact that an individual’s hostile feelings can increase aggressive behavior (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2017) and facilitate collective action (Grant & Brown, 1995). Another possible explanation is that anger is an important component of hostile feelings (Musante et al., 1989), and anger can lead to aggressive collective action online toward an outgroup provocateur (Song et al., 2018). In conclusion, in this study, hostile feelings likely motivated the participants’ aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group.

The mediating effect of hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, we found that group relative deprivation predicts aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group through hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group, which is consistent with existing research concerning the relationship between personal relative deprivation, individual’s hostile feelings, and aggressive behavior (Greitemeyer & Sagioglou, 2017, 2018a). This finding extends the research investigating the effect of relative deprivation on aggression from the individual to the group level and finds that group relative deprivation of undergraduate students increased their hostile feelings toward the college decision-makers within the group (the deprivation-related provocateurs within the group), which, in turn, motivated aggressive collective action online toward the college decision-makers within the group.

Theoretical explanation for mediation model

The frustration–aggression theory and stress and cope theory could provide a theoretical substrate and interpretive lens for the present mediation model, in which group relative deprivation increases aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group. According to frustration–aggression theory (Berkowitz, 1989; Gilbert & Bushman, 2020) and stress and coping theory (Feeney & Fitzgerald, 2022; Lee et al., 2021), group relative deprivation can be thought of as a kind of common frustration and stress for a group. The experience of frustration or stress makes people more sensitive and irritable in response to subsequent provoking events and enhances their hostile feelings triggered by later stressful events. When the stressful event is related to group relative deprivation, the prior sense of group relative deprivation leads group members to have common hostile feelings toward the ingroup provocateur. When the group members are likely to use the Internet, they may share and vent their common hostile feelings online. These shared hostile feelings then drive them to carry out aggressive collective action online toward the provocateur to decrease their psychological stress and change their disadvantaged status, whether the provocateur is an outgroup member or ingroup member.

Contributions and implications

This study has the following contributions. First, our results broaden the existing literature on how the influence object (i.e., ingroup provocateur) of relative deprivation may influence the subclass of aggressive collective action online (i.e., aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group).

Second, this result supports and expands the relative deprivation theory, frustration–aggression theory, and stress and coping theory. The relative deprivation theory focuses on the effect of group relative deprivation on collective action toward the outgroup (Besta et al., 2019; Smith & Huo, 2014; Smith et al., 2012; Smith, Pettigrew et al., 2020; Smith, Blackwood et al., 2020). The present results show that group relative deprivation can lead to a new form of collective action toward the ingroup (i.e., aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group). The frustration–aggression theory suggests that frustration leads to aggressive emotions and behavior (Gilbert & Bushman, 2020). This suggests that group relative deprivation should be a kind of frustration, which can enhance common hostile feelings among group members triggered by a later provoking event that is related to deprivation. Additionally, we have suggested that hostile feelings may be a potential mediator between frustration and aggression. These results enrich the frustration–aggression theory literature and should encourage future researchers to explore the possible mediating effect of other negative feelings on the relationship between frustration and aggression. The stress and coping theory suggests that stressful life event can induce negative emotions, which, in turn, lead to aggressive behavior (Lee et al., 2021). This suggests that it is a stress experience for people who compare their ingroup with outgroups and perceive a comparative disadvantage, and the stress can trigger ingroup members’ hostile feelings, which can lead to aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group.

Third, the results of this study illustrate that inappropriate employment conditions and policies have a negative effect on students’ emotions and behaviors. Thus, colleges and the Ministry of Education should attach importance to undergraduate employment. This has several practical implications. First, colleges should seek to both cultivate students’ knowledge and develop their career planning and interviewing skills. In addition, colleges should provide more employment opportunities to students, for example, inviting more companies to their campuses for recruiting purposes, rather than introducing ineffective policies that place the burden on students to look for a job. These methods will enable colleges to reduce the group relative deprivation of undergraduate students caused by employment problems. Furthermore, when students experience group relative deprivation due to such difficulties, colleges should seek to regulate students’ hostile feelings, such as adopt forgiveness therapy to vent negative affect (Akhtar & Barlow, 2016), to prevent possible aggressive collective action in the future.

Limitations and recommendations for further work

Although this study makes contributions to the field, it also had some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group was measured as a categorical variable. Future studies should measure it as a continuous variable to further verify the results of this study. Second, we used only the triggering behavior of a provocateur as a covariate. However, it may moderate the effect of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online. The moderator (especially the triggering behavior of the provocateur) warrants exploration in future work. Finally, this study was a single study that was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore the effects of the pandemic were not taken into account. The present findings should be replicated. Future researchers in affected countries could use COVID-19 as a measure of group relative deprivation, for example, examining group relative deprivation between countries (e.g., countries with high infection rates and low infection rates) to verify the results of this study.

Conclusions

In summary, this study supports and extends previous work by clarifying the group-related influencing factors of aggressive collective action online. Specifically, this study found that group relative deprivation increases aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group. Importantly, hostile feelings toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group were found to mediate the effect of group relative deprivation on aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related provocateurs within the group. These results support and enrich the relative deprivation theory, frustration–aggression theory, and stress and coping theory.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Akhtar, S., & Barlow, J. (2016). Forgiveness therapy for the promotion of mental well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 19(1), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016637079

Anier, N., Guimond, S., & Dambrun, M. (2016). Relative deprivation and gratification elicit prejudice: Research on the v-curve hypothesis. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.012

Anderson, C. A., Deuser, W. E., & DeNeve, K. M. (1995). Hot temperatures, hostile affect, hostile cognition, and arousal: Tests of a general model of affective aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(5), 434–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295215002

Berkowitz, L. (1989). Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.59

Besta, T., Jurek, P., Iwanowska, M., & Szostakowski, D. (2019). Multiple group membership and collective actions of opinion-based internet groups: The case of protests against abortion law restriction in Poland. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.025

Bogolyubova, O., Panicheva, P., Tikhonov, R., Ivanov, V., & Ledovaya, Y. (2018). Dark personalities on Facebook: Harmful online behaviors and language. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.032

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

Feeney, J. A., & Fitzgerald, J. (2022). Autonomy-connection tensions, stress, and attachment: The case of COVID-19. Current opinion in psychology, 43, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.05.004

Ge, X. (2020). Social media reduce users’ moral sensitivity: Online shaming as a possible consequence. Aggressive Behavior, 46(5), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21904

Gilbert, M. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2020). Frustration-aggression hypothesis. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp.1683–1685). Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3

Grant, P. R., & Brown, R. (1995). From ethnocentrism to collective protest: Responses to relative deprivation and threats to social identity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(3), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787042

Greitemeyer, T., & Sagioglou, C. (2017). Increasing wealth inequality may increase interpersonal hostility: The relationship between personal relative deprivation and aggression. The Journal of Social Psychology, 157(6), 766–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2017.1288078

Greitemeyer, T., & Sagioglou, C. (2018a). The experience of deprivation: Does relative more than absolute status predict hostility? British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(3), 515–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12288

Greitemeyer, T., & Sagioglou, C. (2018b). The impact of personal relative deprivation on aggression over time. The Journal of Social Psychology, 159(6), 664–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2018.1549013

Guimond, S., & Dambrun, M. (2002). When prosperity breeds intergroup hostility: The effects of relative deprivation and relative gratification on prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(7), 900–912. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616720202800704

Gurr, T. R. (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Halevy, N., Chou, E. Y., Cohen, T. R., & Bornstein, G. (2010). Relative deprivation and intergroup competition. Group processes & intergroup relations, 13(6), 685–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430210371639

Iacobucci, D. (2012). Mediation analysis and categorical variables: The final frontier. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(4), 582–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2012.03.006

Iyer, A., Schmader, T., & Lickel, B. (2007). Why individuals protest the perceived transgressions of their country: The role of anger, shame, and guilt. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(4), 572–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206297402

Koomen, W., & Fränkel, E. G. (1992). Effects of experienced discrimination and different forms of relative deprivation among Surinamese, a Dutch ethnic minority group. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 2(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2450020106

Kosakowska-Berezecka, N., Besta, T., Bosson, J. K., Jurek, P., Vandello, J. A., Best, D. L., & Žukauskienė, R. (2020). Country-level and individual‐level predictors of men’s support for gender equality in 42 countries. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(6), 1276–1291. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2696

Lee, J. M., Kim, J., Hong, J. S., & Marsack-Topolewski, C. N. (2021). From bully victimization to aggressive behavior: Applying the problem behavior theory, theory of stress and coping, and general strain theory to explore potential pathways. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22), 10314–10337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519884679

Li, Q. (2007). New bottle but old wine: A research of cyberbullying in schools. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(4), 1777–1791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.10.005

Mackie, D. M., Devos, T., & Smith, E. R. (2000). Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.4.602

MacKinnon, D. P., & Cox, M. G. (2012). Commentary on “Mediation analysis and categorical variables: The final frontier” by Dawn Iacobucci. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(4), 600–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2012.03.009

MacKinnon, D. P., Fritz, M. S., Williams, J., & Lockwood, C. M. (2007). Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods, 39(3), 384–389. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193007

Meuleman, B., Abts, K., Schmidt, P., Pettigrew, T. F., & Davidov, E. (2019). Economic conditions, group relative deprivation and ethnic threat perceptions: A cross-national perspective. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 46(3), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550157

Moore, M. J., Nakano, T., Enomoto, A., & Suda, T. (2012). Anonymity and roles associated with aggressive posts in an online forum. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 861–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.005

Musante, L., Macdougall, J. M., Dembroski, T. M., & Costa, P. T. (1989). Potential for hostility and dimensions of anger. Health Psychology, 8(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.8.3.343

Paterson, J. L., Brown, R., & Walters, M. A. (2019). Feeling for and as a group member: Understanding LGBT victimization via group-based empathy and intergroup emotions. British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(1), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12269

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Bullying and defending behavior: The role of explicit and implicit moral cognition. Journal of School Psychology, 59, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.09.005

Saab, R., Spears, R., Tausch, N., & Sasse, J. (2016). Predicting aggressive collective action based on the efficacy of peaceful and aggressive actions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46(5), 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2193

Smith, E. R. (1993). Social identify and social emotions: Towards new conceptualizations of prejudice. In D. M. Mackie, & D. Hamilton (Eds.), Affect, cognition and stereotyping: Interactive processes in group perception (pp. 297–315). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Smith, H. J., Cronin, T., & Kessler, T. (2008). Anger, fear, or sadness: Faculty members’ emotional reactions to collective pay disadvantage. Political Psychology, 29(2), 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00624.x

Smith, H. J., & Huo, Y. J. (2014). Relative deprivation: How subjective experiences of inequality influence social behavior and health. Policy insights from the behavioral and brain sciences, 1(1), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732214550165

Smith, H. J., Ryan, D. A., Jaurique, A., Pettigrew, T. F., Jetten, J., Ariyanto, A., Autin, F., Ayub, N., Badea, C., Besta, T., Butera, F., Costa-Lopes, R., Cui, L., Fantini, C., Finchilescu, G., Gaertner, L., Gollwitzer, M., G?mez, ?., Gonz?lez, R., Wohl, M. (2018). Cultural values moderate the impact of relative deprivation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49 (8), 1183?1218.https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118784213

Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., & Huo, Y. J. (2020). Relative deprivation theory: Advances and applications. In J. Suls, R. L. Collins, & L. Wheeler (Eds.), Social comparison, judgment, and behavior (pp. 495–526). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190629113.003.0018

Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M., & Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(3), 203–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311430825

Smith, L. G. E., Blackwood, L., & Thomas, E. F. (2020). The need to refocus on the group as the site of radicalization. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(2), 327–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619885870

Smith, T. W., Glazer, K., Ruiz, J. M., & Gallo, L. C. (2004). Hostility, anger, aggressiveness, and coronary heart disease: An interpersonal perspective on personality, emotion, and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1217–1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00296.x

Song, M., Liu, S., Zhu, Z., Zhu, Y., Han, S., & Zhang, L. (2018). Effects of relative deprivation on cyber collective and aggressive behaviors: A moderated dual-pathway models. Journal of Psychological Science, 41(6), 1436–1442. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20180622

Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (2015). Group Identity, Social Influence, and Collective Action Online. In S. S. Sundar (Ed.), The Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology (pp. 23–46). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118426456.ch2

Strong, D. R., Kahler, C. W., Greene, R. L., & Schinka, J. (2005). Isolating a primary dimension within the Cook–Medley hostility scale: A rasch analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.08.011

Tausch, N., & Becker, J. C. (2013). Emotional reactions to success and failure of collective action as predictors of future action intentions: A longitudinal investigation in the context of student protests in Germany. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(3), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2012.02109.x

Tofighi, D., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43(3), 692–700. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x

Tropp, L. R., & Wright, S. C. (1999). Ingroup identification and relative deprivation: An examination across multiple social comparisons. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(5–6), 707–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199908/09)29:5/6>707::AID-EJSP968<3.0.CO;2-Y

Twenge, J. M., Baumeister, R. F., Tice, D. M., & Stucke, T. S. (2001). If you can’t join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1058–1069. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.81.6.1058

van Zomeren, M. (2021). Toward an integrative perspective on distinct positive emotions for political action: Analyzing, comparing, evaluating, and synthesizing three theoretical perspectives. Political Psychology, 42(S1), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12795

van Zomeren, M., & Iyer, A. (2009). Introduction to the social and psychological dynamics of collective action. Journal of Social Issues, 65(4), 645–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01618.x

van Zomeren, M., Leach, C. W., & Spears, R. (2012). Protesters as “passionate economists” a dynamic dual pathway model of approach coping with collective disadvantage. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(2), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311430835

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 134(4), 504–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

van Zomeren, M., Spears, R., Fischer, A. H., & Leach, C. W. (2004). Put your money where your mouth is! Explaining collective action tendencies through group-based anger and group efficacy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 649–664. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.649

Vilanova, F., Beria, F. M., Costa, Â. B., & Koller, S. H. (2017). Deindividuation: From le bon to the social identity model of deindividuation effects. Cogent Psychology, 4(1), 1308104. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2017.1308104

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form.

Wilkins, D. J., Livingstone, A. G., & Levine, M. (2019). All click, no action? Online action, efficacy perceptions, and prior experience combine to affect future collective action. Computers in Human Behavior, 91, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.09.007

Xiong, M., & Ye, Y. (2016). The concept, measurement, influencing factors and effects of relative deprivation. Advances in Psychological Science, 24(3), 438–453. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2016.00438

Yang, X., Wang, Z., Chen, H., & Liu, D. (2018). Cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese adolescents: The role of interparental conflict, moral disengagement, and moral identity. Children and youth services review, 86, 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.003

Yu, G., Zhao, F., Wang, H., & Li, S. (2020). Subjective social class and distrust among Chinese college students: The mediating roles of relative deprivation and belief in a just world. Current Psychology, 39(6), 2221–2230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9908-5

Zhang, S., Wang, E., & Zhou, J. (2012). The motivation mechanism of collective action in different contexts. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44(4), 524–545. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2012.00524

Zubielevitch, E., Sibley, C. G., & Osborne, D. (2020). Chicken or the egg? A cross-lagged panel analysis of group identification and group-based relative deprivation. Group processes & intergroup relations, 23(7), 1032–1048. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430219878782

Funding

This work was funded by the western project of National Social Science Fund of China [grant numbers 20XSH025].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shu Su: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing–original draft. Jiachun Zhang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing–original draft. Ling-Xiang Xia: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Research Project Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the authors’ university and was performed following the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

All participants gave informed written consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, S., Zhang, J. & Xia, LX. The relationship between Group relative deprivation and aggressive collective action online toward deprivation-related Provocateurs within the Group: the mediating role of hostile feelings. Curr Psychol 42, 25246–25256 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03530-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03530-z