Abstract

Although research on laughter is becoming increasingly common, there is no consensus on the description of its variations. Investigating all verbal attributes that relate to the term laughter may lead to a broad set of descriptors deemed important by the speakers of a language. Through a linguistic corpus analysis using the German language, formal attributes of laughter were identified (original pool: 1148 single-word descriptors and 172 multi-word descriptors). A category system was derived in an iterative process, leading to six higher order classes describing formal characteristics of laughter: Basic parameters, intensity, visible aspects, sound, uniqueness, and regulation. Furthermore, 15 raters judged the words for several criteria (appropriateness, positive and negative valence, active and passive use). From these ratings and the prior assignment, a list of attributes suitable for the characterization of laughter in its formal characteristics was derived. By comparing the proposed classification of formal characteristics of laughter with the scientific literature, potential gaps in the current research agenda are pointed out in the final section.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Laughter has been lauded as one of the most important nonverbal communication signals and a universal marker of joy (e.g., Darwin 1872; Ekman and Friesen 1982; Ruch and Ekman 2001). Although laughter is often treated as a homogeneous category, variations not only exist in facial and vocal features (e.g., Bachorowski and Owren 2001, 2003), but also in elicitors and functions (e.g., Hofmann et al. 2017). Thus, the question arises of how best to classify it: Should different laughter “types” be distinguished? Or is laughter best described among several descriptive dimensions?

Several authors worked with a basic binary distinction of emotional (spontaneous) versus voluntary (posed) laughter (Davila-Ross et al. 2011; Gervais and Wilson 2005; Keltner and Bonnanno 1997; Ruch and Ekman 2001; Ruch et al. 2013, Vlahovic et al. 2012). Yet, those categories are still very broad. For example, spontaneous laughter due to embarrassment (as an elicitor) or amusement may differ in their nonverbal expression (Ruch et al. 2013). Thus, while this distinction between spontaneous and posed laughter is important for the study of laughter in social interactions, it is probably not fine-grained enough to account for the variety of expressive features going along with laughter based on different elicitors.

Several authors have suggested laughter classifications basing on morphological features, such as facial expression (distinguishing between Duchenne and non-Duchenne laughter; e.g., Keltner and Bonnanno 1997; Ruch 1990; Ruch and Ekman 2001) or vocal features (e.g., Bachorowski et al. 2001). Other attempts base on the assumption that laughter occurs in a variety of negative and positive emotions, and serves conversational/social functions (e.g., Glenn 2003; Holt 2012; Poyatos 1993; Ruch et al. 2013; Wildgruber et al. 2013). For example, terms like contemptuous, nervous, or malicious laughter are frequently found (e.g., Battista et al. 2012), and attempts were made to distinguish among them at a morphological basis. Thus, classifications may base on the elicitor of the laughter, like an emotion or a physical elicitor (e.g., laughing gas).

Ruch et al. (2013) specified the factors that might lead to different laughter variants/types. They summarized that laughter variations may be determined by: (1) the type of eliciting stimulus (e.g., an unexpected hoax, tickling, positive emotion, see for example Hofmann et al. 2015b, 2017; Wildgruber et al. 2013), (2) the social situation (e.g., being with friends, an authority figure, or a stranger; Devereux and Ginsburg 2001; Mehu and Dunbar 2008), (3) habitual/dispositional factors (e.g., body constitution, personality traits; see Hall and Allin 1897; La Pointe et al. 1990; Navarro et al. 2014) which may alter laughter expressions, (4) current affective states (e.g., motivational states like sexual interest, see Grammer and Eibl-Eibesfeldt 1990; Van Hooff 1972), (5) organismic states (e.g., fatigued, intoxicated, energetic, e.g., Ruch 2005), and (6) cognitive factors (e.g., awareness of situational demands or display rules, strategic self–presentation, e.g., Ceschi and Scherer 2003; Scherer and Ellgring 2007) which may alter the expression of laughter (visible, audible) and the subsequent perception of different laughter variants/types.

Further, Ruch et al. (2013) argued that if such variations exist, they would be encoded into language (e.g., “nervous” laughter, Battista et al. 2012), apparent in the different nonverbal channels, or at least some of them (e.g., vocalization, facial expression, body motion), and that there would be different antecedents, as well as social and affective consequences (Ruch et al. 2013). Variations would not only occur due to differences in spontaneous laughter but also due to intensity (see Hempelmann and Gironzetti 2015; Hofmann 2014) and voluntary attempts to regulate spontaneous laughter, as well as using laughter to mask emotional states or to feign emotional arousal (i.e., Darwin 1872 and McComas 1923, theorized that laughter might be used to mask anger, shame, or nervousness). Ruch et al. (2013) further postulated that qualitative differences between laughter types would be the core of such a classification (rather than mere quantitative differences; e.g., in duration), but that it is questionable whether these types coming from the language would also be based on physiological and morphological differences (i.e., different muscular involvement; Ruch et al. 2013). Categories may just be artifacts, emerging from different perspectives: For example, the laughing person might experience amusement at a person’s unexpected mishap, the unfortunate person might perceive it as “mean laughter” (as the person got into an uncomfortable situation) and an observer might consider it “malicious laughter”. To summarize, laughter classifications that focus on the elicitors would come to different results than classifications based on morphological features (Ruch et al. 2013).

There are currently several different schemes that classify laughter in terms of varying sets of features. Some classifications overlap, and some are independent of each other (i.e., classifications that either categorize in terms of facial expressions or auditory features). Yet, it would be valuable to have a classification that includes all modalities of laughter expression and hence one that could serve as a common denominator for researchers of different fields.

One approach to arrive at a broad, modality over-arching classification would be to assess all words a language created to describe the phenomenon (see Huber 2011; Ruch and Wagner 2015). Basing on the assumption that every important difference/quality is represented in a verbal label (encoded into language) this is a way to cover the variety of laughter comprehensively. Being an atheoretical approach this will help not to overlook variations where no studies exist so far. Then, in a next step, the laughter descriptors can be classified to derive broad dimensions influencing the laughter expression/elicitation, etc. Supposedly, such classifications are the most comprehensive of all classifications, as they unite all noticeable/relevant features that humans need to describe laughter (see e.g., Allport 1937; Goldberg 1982). Thus, we shift our focus from classifying laughter to classifying laughter terms. The study of the lexical field will allow first identifying parameters along which laughter varies and later examining the morphological and physiological parameters underlying these perceptual dimensions. Likewise, in further studies, the lexical field will also allow building classifications of laughter terms in different domains (e.g., person-related, emotion-related) to then later examine these against other domains (e.g., emotional tone, person characteristics). Perceptual differences in laughter were first sampled with a lexical analysis that attempts, for one language, to extract laughter qualities. A search of linguistic corpora was used to generate a list of attributes of laughter that describe all of its formal characteristics in the German language.

Aims of Present Study

The aims of this study were fourfold: First, we wanted to identify all German words describing attributes of laughter (Study 1). For this purpose, a number of online corpora with several billion entries were examined and the statements including laughter were then collected in a pool of terms. Second, we wanted to generate a classification for the subset of formal laughter attributes (Study 1). Third, we aimed at characterizing the descriptors of formal laughter attributes gathered in Study 1 by collecting ratings on their appropriateness to describe laughter and their valence (Study 2). Finally, we aimed at discussing the proposed classification in the light of existing domains and results from the literature on the science of laughter.

Study 1

Selection of the Words

Choice of Corpora

In order to obtain a nearly exhaustive list of terms that can be used to describe laughter in the German language, we screened a variety of linguistic corpora and dictionaries. The corpora are described in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that the corpora include a broad variety of text forms (fiction and non-fiction, i.e. newspaper articles, scientific and functional literature, and transcripts of spoken language), mostly from the 20th and twenty-first century. Only a minority of the corpora available also included transcriptions of spoken language, but since we were not interested in comparing the frequencies of descriptors, but only in generating a list of descriptors used, the selection of corpora seemed suitable to cover the whole range of written and spoken use of the German language.

Identification of Words

In the corpora listed in Table 1, a search for any flection of “to laugh” (in German: “lachen”) or “laughter” (in German: “Lachen”) was conducted between September and November 2012, supported by the technical solutions of several of the corpora (e.g., a total of 46 different flections was taken into account by the COSMAS-II database). Within those results, we examined all terms that co-occurred with any of those flections, i.e., that appeared in sentence together with a flection of “to laugh” or “laughter” within a range of 5 words before or after the flection. One of the authors looked through all entries (altogether more than 250,000) using two inclusion criteria: the sentence described or further specified 1) a laughter event (e.g., “it was a loud laugh“) or 2) the way a person laughed (e.g., “she laughed wholeheartedly”). In case of doubt, the author consulted with one of the co-authors. Using these criteria, a definite decision on inclusion could be taken for all of the entries. Overall, the search yielded a total of 1148 different single-word terms (mainly adjectives) and 172 expressions consisting of more than one word (e.g., to split one’s sides laughing [sich vor Lachen biegen]). For further analyses, only single-word terms were used.

Categorization

The next step consisted of grouping the adjectives for content proximity and iteratively deriving a category system to describe attributes of laughter. We found that at a global level the words could be classified into broad categories, such as formal characteristics, style categories (relating to type of communication, emotional qualities, mental states), terms reflecting individual differences, person-describing terms and purely evaluative terms. For the present study we focused on terms describing the formal attributes of laughter leaving out all adjectives that represent the expression of emotions, communicative and social functions of laughter, mental states of the person laughing, and the purely evaluative terms (as the latter may not be subject to consensus when context information is missing).

The classification of formal characteristics of laughter was generated in an iterative process. Firstly, we grouped words according to their content proximity/resemblance. We started by extracting words that describe certain aspects and then turning to the remaining terms and extracting further categories (example: all words relating to the sound of laughter were grouped together, then the remaining words were considered). During this process we consulted dictionaries, linguists and experts in laughter research. These experts also helped us construct same-level subcategories and higher order categories. This hierarchically structured category system will allow us to do analyses on the main and sub category levels in the future. After the initial set of categories was established, it was iteratively refined with help from a group of experts in laughter research.

Within this initial classification system of the formal attributes of laughter, laughter is described by terms that relate to (1) basic parameters of the signal laughter (e.g., duration), (2) how intense the laughter is (in terms of power, dynamism, and involvement of the body), (3) how it looks (i.e., observable visual qualities), (4) how it sounds (i.e., perceived audible qualities), (5) whether it expresses a person’s uniqueness, and (6) whether and how it is regulated or modified (i.e., intensified, de-intensified, simulated, forced, or unregulated). Of the total list of 1148 words (including e.g., emotional and evaluative terms), 43.6% (501 words) were assigned to one of these six categories. Of the reduced list of 857 words (based on the ratings obtained in Study 2), 44.2% (379 words) were assigned to one of these six categories; i.e., to the formal attributes.

Table 2 shows the higher and lower order categories on the formal attributes of laughter. For each subcategory, a few examples (translated into English) are given. In more detail, the first superordinate category denominates basic parameters of laughter and contains adjectives describing the parameters that laughter has in common with other signals. Those parameters include the noticeable presence or absence of a trigger (1.1), the latency of the response (1.2), the characteristics of the time course (1.3) and the duration (1.4). Thus, these categories describe the sequence between the act of a trigger, the activation of the response and a variety of formal differences in spatio-temporal action and its frequency.

The analysis revealed that people notice whether laughter happens with a reason or is shown in the apparent absence of a trigger (be it generally absent or just not known to the observer). There are 13 words in the category presence or absence of a trigger (1.1) of which twelve refer to no reason, e.g. motiveless (unmotiviert) or causeless (grundlos), and one word describing the laughter reaction as appropriate (angemessen).

The latency (1.2) of the laughter event refers to the time between the perceived trigger or reason for the laughter response and the onset of the response. If the latency is short, the laughter might be described as abrupt (plötzlich) or sudden (jäh). If it is rather long, it might be called delayed (verzögert) or hesitant (zögerlich). There are 19 words in this category, of which 15 words describe a short latency and four words a long latency.

Twenty laughter descriptions refer to differences in the time course of the signal (1.3). These differences include variations in the steepness of onset of laughter (4 words), which can be described by either an outburst quality (i.e., explosive [explosiv]) or by only gradually getting louder. This parameter describes where the maximal point of intensity is compared to onset and offset. If the energy is at the outset the laughter will be labeled as being explosive. Group laughter (maybe also individual laughter) may have a late peak when, for example, the eliciting stimulus unfolds its power only gradually (slow realization of the humor in a situation) or when contagiousness adds to the (total group) laughter. Eight adjectives in this category describe changes in the intensity over time, which in most cases means the absence or presence of discontinuities in the signal. If the signal is discontinued, the laughter is referred to as jerky (stoßartig), stagnant (stockend) or clipped (abgehackt). If the signal doesn’t display any discontinuities, it is described as steady (ununterbrochen). A third aspect of the signal’s time course is characteristics of its decay/offset (8 words). This can either be with an abrupt and perhaps unexpected ending, e.g. discountinued (abgebrochen), wrenched off (abgerissen), shattering (zerschellend), or it can slowly and gradually fade out, e.g. ebbing away (abschwellend). In the former case, most likely a changed psychological state made the laughter cease; e.g., an unexpected turn of the situation that rendered the situation serious or other events. The latter category seems to refer more to a naturally fading out of laughter.

Duration (1.4) characterizes the length of time during which the signal lasts and this category includes 23 words. Adjectives describing the duration of laughter include evanescent (flüchtig), brief (kurz), sustained (anhaltend) and endless (endlos). Five adjectives describe rather short laughter, 18 describe laughter perceived as rather or even extraordinarily long.

The second superordinate category is intensity. It contains all adjectives that relate to power and dynamism (2.1) in the laughter, vitality (2.2) as well as the degree to which the whole body is involved (2.3). Powerful and dynamic laughter (2.1) is carried out forcefully. There are 22 words in this subcategory, of which 14 describe a high level of power, including strong (stark) and forceful (kräftig). On the opposite end of this dimension, 8 words describe a low level of power, e.g. weak (schwach) or gentle (sanft).

Vitality (2.2) refers to words describing laughter as having a lively and energetic quality. The 30 words in this category include vivacious (lebhaft) and vital (vital) as well as tired (müde) or weary (matt) at the other end of the dimension. Twenty-five words in this category refer to highly or very highly intense laughter, five words to laughter of lower intensity.

The analysis also revealed a number of adjectives (n = 11) that express the intensity of laughter by referring to the degree to which the body is involved when laughing (2.3). The majority of those words describe a strong involvement of the body in laughing. When laughter is referred to as quivering (bebend) or spasmodic (krampfartig), it is not just involving the face and the voice but more or less the whole body. One adjective also describes the opposite state – the body not being involved in laughing, i.e., without movement (bewegungslos).

The third superordinate category is visible aspects. It contains 33 adjectives describing aspects of the appearance of laughter that can be observed without hearing anything, e.g. blushing (errötend) or lopsided (schief).

Containing the most words of the six categories (in total 184), the fourth superordinate category is sound. It consists of adjectives describing the way laughter sounds. Its subcategories include auditory description (4.1), respiration (4.2), articulation (4.3), phonation (4.4), rhythm (4.5), body involvement in sound (4.6), and metaphorical or auditory-metaphorical description (4.7).

There are 57 adjectives that relate to the auditory description (4.1). They are descriptors of how a sound is perceived and are words that are mostly used to describe sounds. These words mostly describe the perceived loudness of the signal (varying from quiet [leise] or unhearable [lautlos] to loud [laut] or boisterous [lärmend], overall 15 adjectives exclusively describe different levels of loudness). Thus, there are two categories that describe the magnitude of laughter but focus on different aspects: auditory description (4.1), which includes the perceived loudness, and intensity (2), which describes power, vitality, and involvement of the body. The second group of words in the category auditory description refers to sound qualities such as pitch and timbre (i.e., what makes the sounds of two laughter events different, even if they have the same duration and loudness, though some of the words are also associated with a certain level of loudness). Those include adjectives such as piercing (schrill) or resounding (schallend), 42 adjectives describe these sound qualities.

Respiration (4.2) describes the way that differences in breathing influence the sound of a laughter signal. The eight adjectives in this category include word like breathless (atemlos) or gasping (schnaufend). Similarly, eight adjectives were categorized as describing the way that differences in articulation (4.3) influence the sound of laughter, e.g., nasal (näselnd) or chirruping (schnalzend). The impact of differences in phonation (4.4) on the sound of laughter is captured by 16 adjectives, including breathy (gehaucht) or pressed (gepresst). Two words (e.g., wobbling [kullernd]) describe sound variations created by different rhythms (4.5) of laughter and eight words refer to sounds that are produced by some involvement of the body (4.6) in producing the sound (e.g., coughing [hustend]) or in the reaction to the sound (e.g., side-splitting [zwerchfellerschütternd]).

There were also quite many (85) words that describe the sound of a laughter event by using a metaphorical description (4.7). Some of these metaphorical descriptions include words that are common metaphors when referring to a sound (e.g., high [hoch] or deep [tief] as descriptors of the pitch level) and can also be called auditory-metaphorical descriptions. There is also a larger group of adjectives that referred to animal sounds (e.g., whinnying [wiehernd] or cackling [schnatternd], 10 words altogether). Another larger group involves characterizing laughter by a musical metaphor. Examples of those seven attributes include dissonant (misstönend) or melodic (melodisch). Other metaphors compare the laughter sound to other sounds, such as ringing (klingelnd) or bell-like (glockenhell). A final group of words includes metaphors that refer to qualities that are not necessarily typical to describe sounds, such as dry (trocken) or cold (kalt).

There are a number of adjectives that relate to the fact that laughter can express a person’s individuality or uniqueness. The fifth superordinate category includes those 32 adjectives describing the uniqueness of a laughter response. Among those words, there are two subcategories. Laughter can have a fingerprint quality (5.1) meaning that the laughter is so typical of a person that it is clearly distinguishable from others and that one can eventually identify a person only hearing her/him laughing. This subcategory comprises of 13 adjectives, such as incomparable (unvergleichlich), inimitable (unnachahmlich) and world famous (weltberühmt). The other way of expressing uniqueness is by referring to more general descriptions of common (5.2) laughter, which is captured by the second subcategory. Seven adjectives describe ordinary laughter, including unremarkable (unauffällig) and conventional (konventionell) while 12 words describe extraordinary laughter, including uncommon (ungewöhnlich) and strange (eigenartig). Adjectives in the latter group are different from adjectives in subcategory 5.1 in the sense that they don’t relate to laughter as being characteristic of a specific individual but to the extent to which the laughter signal deviates from a prototypical laugther event.

Finally, the sixth superordinate category is regulation. It includes all words referencing to some sort of regulation or conscious modification of laughter or the noticeable absence of it. Accordingly, the subcategories describe de-intensified laughter (6.1.1), intensified laughter (6.1.2), distorted laughter (6.1.3) as well as unregulated laughter (6.2).

De-intensified laughter (6.1.1) is a type of laughter that is intentionally regulated to be less loud or less long than it would naturally be. Thus, the expression of an emotion is down-regulated. The 24 terms in this subcategory range from slightly de-intensified, e.g. restrained (verhalten) or hesitant (zaghaft), to scarcely or not at all audible, e.g. suppressed (unterdrückt) or denied (verkniffen).

On the opposite side, intensified laughter (6.1.2) means laughter that is intentionally regulated to be louder or longer than it would naturally be. That is, an emotion may be present, but it is intentionally up-regulated to seem stronger. The three adjectives describing intensified laughter include exaggerated (übertrieben) and effusive (exaltiert).

The subcategory simulated laughter (6.1.3) includes all terms that describe laughter events that don’t occur as an expression of an experienced emotion but are intentionally induced. Examples of the 24 adjectives in this subcategory include artificial (künstlich), insincere (aufgesetzt) or disingenuous (unaufrichtig).

Forced laughter (6.1.4) describes laughter that is observed in situations when a person does not feel like laughing, but is intentionally producing a laugh anyway. The eight adjectives in this subcategory include reluctant (widerwillig) and tense (verkrampft).

Unregulated laughter (6.2) depicts the absence of any regulatory or modifying influences that are described in the previous subcategories. Some of the 53 adjectives in this subcategory explicitly refer to the absence of regulation, such as uninhibited (ungehemmt), unrestrained (zügellos). Other terms in this subcategory rather refer to the authenticity of the laughter, implying but not directly mentioning the absence of regulation, e.g., genuine (echt), wild (wild) or sincere (ehrlich).

Discussion

Focusing on formal attributes of laughter, a classification with six higher order categories was obtained by expert agreement. The generation of the higher order categories followed quite naturally as the attributes mostly fell into relatively clear categories of parameters. Only the subcategories required discussion and were occasionally revised. Terms concerning emotions, the communicative and social functions of laughter, features of the laughing person, and also purely evaluative terms were omitted, as those assignments depend on the context and the subjective interpretation of the decoder naming the laughter.

The terms gathered and used in this study were included if they occurred at least once in the corpora used. As a consequence, some terms might not generally be considered appropriate to describe laughter, but only be used very idiosyncratically in a specific context. To filter out these terms and to also characterize the descriptors of formal laughter in terms of their valence, we conducted Study 2.

Study 2

Method

Participants

A sample of N = 15 students (11 female, 4 male) with a mean age of 24.67 years (SD = 2.74; range: 20–30 years) participated in the rating study. All of them were native German speakers. Ten raters completed the ratings for the full list of attributes, five for a subset of them.

Ratings

Participants were asked to rate appropriateness (How appropriate is the adjective to describe laughter? on a scale ranging from “1 = not at all appropriate” to “6 = exceptionally appropriate” and “0 = don’t know the meaning of the word), valence (How positive or negative is the word when used together with laughter?) on a scale ranging from “+3 = very positive” to “-3 = very negative” (and an option to not judge the valence, i.e., “I don’t know”), active use (Have you ever used the word to describe laughter? “yes”/“no”) and passive use (Have you ever heard or read the word being used to describe laughter? “yes”/“no”).

Procedure

Participants were recruited via a university mailing list. The participants were asked to rate each of the 1148 adjectives originally identified in Study 1 (presented in a randomized order) in an online questionnaire on four criteria: appropriateness, valence, active use, and passive use. The ratings took between four and six hours to complete and the participants were asked to take several breaks in order to be able to keep up their concentration. All participants gave informed consent to the participation and participated voluntarily. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Results

First, descriptive statistics for the ratings were computed. Mean appropriateness ratings ranged from 1.40 (lateinamerikanisches Lachen/Latin American laughter) to 5.50 (ansteckendes Lachen/contagious laughter), with a mean of 3.47 (SD = 0.75). The percentage of raters who had used an attribute to describe laughter or read or heard it in this context ranged from 0 to 100% with a mean of 45.1% (passive use) and 26.1% (active use), respectively. Mean valence ratings ranged from −2.60 (abfälliges Lachen/disparaging laughter) to 2.78 (strahlendes Lachen/radiant laughter). Table 3 shows the distribution of appropriateness ratings when summarized into 5 groups as well as the mean percentages of passive and active use and the mean valence ratings.

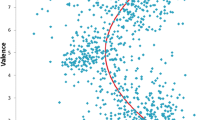

As shown in Table 3, the average percentage of raters who have used a word to describe laughter (active use) as well as the average percentage of raters who have heard or read the word describing laughter (passive use) increases as the appropriateness ratings increase. This supports the validity of the appropriateness rating. Next, correlations between the mean appropriateness and mean valence ratings were computed. Overall, there is a positive correlation between the mean appropriateness rating and the mean valence rating (r = .23; p < .001). Yet, the relationship between the ratings may not be best described by a linear function (see Fig. 1).

As Fig. 1 shows, the scatterplot between valence and appropriateness indicates both a linear (r = .23; p < .001) and quadratic trend (r = .46; p < .001). Words of more extreme valence also appeared to be more appropriate to describe laughter; with increasing (positive and negative) valence also the appropriateness of laughter increases. The linear trend implies that the positive scores also received the higher appropriateness scores. The latter is plausible as it reflects the general tendency of laughter to be positively valued.

Discussion

Six Higher Order Categories to Describe Laughter

Investigating corpora of the German language revealed a very large number of words that were used to qualify laughter. A small subgroup of them can be identified as somewhat idiosyncratic; they do not mean much in everyday conversation and might have been only used in one or very few contexts. However, the majority of the attributes can be classified as appropriate to describe laughter and they cover a rich variety of aspects relating to laughter. Formal attributes of laughter (basic parameters, intensity, visible aspects, sound, uniqueness, and regulation) account for almost half of the attributes found in descriptions of laughter within the German corpora. Figure 2 visualizes the findings from the current study.

Six higher order categories and subcategories of laughter words. (Note. The numbers in brackets indicate the total words that exceeded the cut off-value in the ratings (Study 2). The subcategories were arranged on the y-axis after reviewing the words contained in them regarding the extent to which these could potentially be objectively measured. The arrangement of the categories represent an approximation based on agreement among the authors)

We explicitly omitted purely evaluative terms and reserved terms relating to emotions (e.g., lacerated/verwundet, angry/zornig), communicative functions (e.g., pejorative/abwertend, affirmative/zustimmend), mental states (e.g., indifferent/gleichgültig, puzzled/ratlos) and personality (e.g., tomboyish/burschikos, roguish/spitzbübisch) for potential future study. The formal attributes were more easily determined and are less subject to interpretation. We assume that the remaining terms will be more difficult to study as they reflect that they either depend on factors within the decoder or the encoder. In terms of emotions those terms depend on the encoder and may not even be observable by the decoder. Moreover, the terms relating to emotions, functions and evaluation may not be mutually exclusive to the classification of formal characteristics, as they denominate elicitors (i.e., emotions; functions) and cognitive/emotional aspects (i.e., evaluation).

When looking at the relationship between the appropriateness and valence ratings, we found both a linear and a quadratic correlation. Overall, positive attributes are seen as more suitable to describe laughter. This might be a result of laughter being perceived as a primarily positive phenomenon in general and fits to the replicated findings of laughter being a positively evaluated nonverbal signal (e.g., Darwin 1872; Ekman and Friesen 1982; Ruch and Ekman 2001; Sauter et al. 2010). Above that, the quadratic correlation suggests that terms that are seen as more appropriate to characterize laughter are likely also seen as very positive or as very negative. The appropriate terms are less likely seen as neutral. This finding suggests that laughter is typically associated with the expression of emotions.

In the present study, no identification of people with a fear of being laughed at was undertaken (Ruch et al. 2014) at the level of raters. For gelotophobes, the laughter words would generally have a more negative valence, or the negativity would be more pronounced as compared to individuals with no fear of being laughed at (e.g., Hofmann et al. 2015a; Papousek et al. 2014; for a review, see Ruch et al. 2014). One might also ask, whether the richness of the negative vocabulary in describing laughter actually stems from gelotophobes or aghelastos/misoghelus (i.e., laughter haters). An alternative hypothesis would be that laughter is not only misinterpreted as negative by gelotophobes and their kin, but may indeed be used as a weapon too (e.g., Ferguson and Ford 2008), explaining the number of negative terms.

The relevance of the dimensions of formal laughter characteristics derived from Study 1 is also demonstrated by an additional study (Ruch and Wagner 2015) that suggests that these dimensions can be useful to characterize different kinds of laughter, which vary in valence. Ruch and Wagner (2015) used different labels denoting affective and motivational states (that are not part of formal laughter characteristics) identified from previous research (e.g., mocking laughter, embarrassed laughter or laughter elicited by tickling, see Hofmann et al. 2017; Kori 1987; Platt et al. 2013; Ruch et al. 2009). Participants rated these kinds of laughter, on several dimensions that were derived from the classification of formal laughter attributes presented in Study 1. A hierarchical cluster analysis of these ratings showed that the different kinds of laughter fell into five clusters that were distinguishable in regard to the formal aspects (as well as in regard to the valence). For instance, one cluster consisted of the adjectives cold-hearted, mocking, and scornful and was characterized among others by an abrupt ending, a short duration, little movement, and strong regulation (see Ruch and Wagner 2015). These findings underline that the formal characteristics identified in Study 1 are relevant to describing laughter with different underlying emotions and motivations.

Comparing Classification and Descriptive Systems?

In previous studies, different systems to distinguish between laughter characteristics have been put forward and used. Most often, the systems or descriptive dimensions stemmed from parameters typically used when studying a certain laughter modality (i.e., the sound). In the following section, we have started a preliminary attempt to integrate the previously used descriptors and systems with our proposal of six higher order formal characteristics. Both, classifications basing on morphology with a focus on facial features (see Ruch and Ekman 2001) and auditory features (for example Bachorowski et al. 2001) may be linked to the current proposal. Table 4 shows an overview on the links between the current proposal and existing descriptive systems and classifications.

Table 4 shows that the features of most formal characteristics and subcategories have already been studied with objective parameters (e.g., facial feature coding, acoustic analyses). Yet, because all emotion and elicitor-related terms were excluded, no system based on the eliciting stimulus or emotion can be linked to the currently proposed system (for example, Hawk et al. 2009; Ruch et al. 2013; Wildgruber et al. 2013). Furthermore, other researchers have categorized laughter according to its function in conversations. Some of those distinctions may also be found in the formal characteristics, especially those concerning basic parameters and regulation of the display. Yet other functions, such as topic determination, complaints, etc. may not be well represented in the classification of formal characteristics (for research on conversational functions, see Attardo et al. 2013; Bonin et al. 2014; Clift 2012; Guardiola and Bertrand 2013; Holt 2012; Partington 2011; Vettin and Todt 2004; Walker 2013).

Limitations

An obvious limitation of our approach is that it uses German corpora as the starting point. While findings from our analyses may apply to other languages as well, studies using different languages are needed to replicate the results. As Hempelmann and Gironzetti (2015) point out, languages differ in the way they encode laughter variations. They note that the German language (and other Germanic languages, such as English) include different verbs for describing laughter (such as “gackern” or “cackle”) whereas other languages such as Arabic, Chinese, or Japanese use adverbs or prepositional phrases to express those variations. Since the present study focused on attributes used to describe laughter while focusing on the terms “to laugh” and “laughter”, such differences between languages may not be of large concern.

Nonetheless, cultural differences with regard to the perception of humor and laughter (see e.g., Jiang et al. 2019; Proyer et al. 2009) can be assumed to impact the way that laughter variations are encoded in different languages. Differences between languages and cultures might be especially relevant when going beyond the formal parameters of the utterance (that can be assumed to be more universal) are investigated (e.g., emotional, motivational qualities). These qualities also need attention in German, which is a next step in this line of research. Another limitation is that right now we do not know whether these terms would be used consistently when judging a set of laughter events. Thus, we need to know whether a laughter checklist could be used with high intersubjectivity; if so, then this list could be used in studies, to then eventually be related to measured objective parameters. While some of the parameters seem to reflect natural dimensions (duration, loudness) others are of a more qualitative nature. Future research will show whether they can be matched with a measured entity.

Outlook

The classification points towards gaps in the current research agenda. A number of aspects that appeared in the corpus analysis and in the classification involve facets that have been understudied or not yet studied at all. As a consequence, the classification might help stimulate research in these areas. One of the most elusive characteristics is the “fingerprint quality” of laughter. It is often assumed that laughter is a sort of identity call; i.e., it allows an observer to identify the person laughing even if they are far away. This might have been especially important before we developed speech. Indeed, we seem to be able to identify laughs of a friend against the background noise of many people laughing at a party. This fingerprint quality might be the most difficult to identify, and might take longest. However, it will be a combination of parameters, and their underlying physical entities. Such studies will also need to consider that group identity (different nationalities; in-group, a close out-group, a distant out-group) cannot be inferred from laughter (Ritter and Sauter 2017).

References

Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. New York: Holt.

Attardo, S., Pickering, L., Lomotey, F., & Menjo, S. (2013). Multimodality in conversational Humor. Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 11, 402–416. https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.11.2.12att.

Bachorowski, J.–. A., & Owren, M. J. (2001). Not all laughs are alike: Voiced but not unvoiced laughter readily elicits positive affect. Psychological Science, 12, 252–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00346.

Bachorowski, J.–. A., & Owren, M. J. (2003). Sounds of emotion. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1000, 244–265. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1280.012.

Bachorowski, J.–. A., Smoski, M. J., & Owren, M. J. (2001). The acoustic features of human laughter. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 110, 1581–1597. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1391244.

Battista, S. R., MacDonald, D., & Stewart, S. H. (2012). The effects of alcohol on safety behaviors in socially anxious individuals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31, 1074–1094. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2012.31.10.1074.

Bonin, F., Campbell, N., & Vogel, C. (2014). Time for laughter. Knowledge–Based Systems., 71, 14–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2014.04.031.

Ceschi, G., & Scherer, K. (2003). Children's ability to control the facial expression of laughter and smiling: Knowledge and behaviour. Cognition and Emotion, 17, 385–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930143000725.

Clift, R. (2012). Identifying action: Laughter in non–humorous reported speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 44, 1303–1312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.06.005.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: John Murray.

Davila-Ross, M., Allcock, B., Thomas, C., & Bard, K. A. (2011). Aping expressions? Chimpanzees produce distinct laugh types when responding to laughter of others. Emotion, 11, 1013–1020. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022594.

Devereux, P. G., & Ginsburg, G. P. (2001). Sociality effects on the production of laughter. Journal of General Psychology, 128, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221300109598910.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1982). Felt, false and miserable smiles. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 6, 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00987191.

Ferguson, M. A., & Ford, T. E. (2008). Disparagement humor: A theoretical and empirical review of psychoanalytic, superiority, and social identity theories. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. https://doi.org/10.1515/HUMOR.2008.014.

Gervais, M., & Wilson, D. S. (2005). The evolution and functions of laughter and humor: A synthetic approach. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80, 395–430. https://doi.org/10.1086/498281.

Geyken, A. (2007). The DWDS Corpus: A reference corpus for the German language of the 20th century. In C. Fellbaum (Ed.), Collocations and idioms: Linguistic, lexicographic, and computational aspects. London: Continuum Press.

Glenn, P. (2003). Laughter in interaction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Goldberg, L. R. (1982). From ace to zombie: Some explorations in the language of personality. In C. D. Spielberger & J. N. Butcher (Eds.), Advances in Personality Assessment (Vol. 1, pp. 203–234). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Grammer, K., & Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. (1990). The ritualisation of laughter. In W. A. Koch (Ed.), Natürlichkeit der Sprache und der Kultur (pp. 192–214). Bochum, Germany: Brockmeyer.

Guardiola, M., & Bertrand, R. (2013). Interactional convergence in conversational storytelling: When reported speech is a cue of alignment and/or affiliation. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00705.

Hall, G. S., & Allin, A. (1897). The psychology of tickling, laughing, and the comic. The American Journal of Psychology, 9, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/1411471.

Hawk, S. T., Van Kleef, G. A., Fischer, A. H., & Van der Schalk, J. (2009). Worth a thousand words: Absolute and relative decoding of nonlinguistic affect vocalizations. Emotion, 9, 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015178.

Hempelmann, C. F., & Gironzetti, E. (2015). An interlingual study of the lexico-semantic field laugh in Ken Kesey’s one flew over the Cuckoo’s nest. Journal of Literary Semantics, 44, 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1515/jls-2015-0008.

Hofmann, J. (2014). Intense or malicious? The decoding of eyebrow-lowering frowning in laughter animations depends on the presentation mode. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01306.

Hofmann, J., Platt, T., Ruch, W., & Proyer, R. (2015a). Individual differences in gelotophobia predict responses to joy and contempt. Sage Open, 5(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015581191.

Hofmann, J., Platt, T., Ruch, W., Niewiadomski, R., & Urbain, J. (2015b). The influence of a virtual companion on amusement when watching funny films. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 434–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9461-y.

Hofmann, J., Platt, T., & Ruch, W. (2017). Laughter and smiling in 16 positive emotions. IEEE Transactions in Affective Computing, Special Issue on Laughter, 8, 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2017.2737000.

Holt, L. (2012). Using laugh responses to defuse complaints. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 45, 430–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.726886.

Huber, T. (2011). Enkodierung und Dekodierung verschiedener Arten des Lachens. Eine FACS basierte Studie mit Schauspielern [Encoding and decoding of different types of laughter. A FACS based study with actors]. Unpublished thesis, University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Jiang, T., Li, H., & Hou, Y. (2019). Cultural differences in humor perception, usage, and implications. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 123. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00123.

Keltner, D., & Bonnanno, G. A. (1997). A study of laughter and dissociations: Distinct correlates of laughter and smiling during bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.687.

Kori, S. (1987). Perceptual dimensions of laughter and their acoustic correlates. XIth Inter-national Congress of the Phonetic Sciences, 4, 255–258.

Kupietz, M., Belica, C., Keibel, H., & Witt, A. (2010a). The German reference corpus DeReKo: A primordial sample for linguistic research. In N. Calzolari, K. Choukri, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, J. Odijk, S. Piperidis, M. Rosner & D. Tapias (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th conference on International Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2010) (pp. 1848–1854). Valletta, Malta: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

Kupietz, M., Belica, C., Keibel, H., & Witt, A. (2010b). The German Reference Corpus DeReKo: A primordial sample for linguistic research (p. 2010). LREC.

La Pointe, L. L., Mowrer, D. M., & Case, J. L. (1990). A comparative acoustic analysis of the laugh responses of 20–and 70–year–old males. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 31, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2190/GU55-AF9Q-M586-4HM3.

McComas, H. C. (1923). The origin of laughter. Psychological Review, 30(1), 45–55.

Mehu, M., & Dunbar, R. (2008). Naturalistic observations of smiling and laughter in human group interactions. Behaviour, 145, 1747–1780. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853908786279619.

Navarro, J., Del Moral, R., Alonso, M. F., Loste, P., Garcia-Campayo, J., Lahoz-Beltra, R., & Marijuán, P. C. (2014). Validation of laughter for diagnosis and evaluation of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 160, 43–49.

Papousek, I., Aydin, N., Lackner, H. K., Weiss, E. M., Bühner, M., Schulter, G., Charlesworth, C., & Freudenthaler, H. (2014). Laughter as a social rejection cue: Gelotophobia and transient cardiac responses to other persons' laughter and insult. Psychophysiology. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12259.

Partington, A. (2011). “Double–speak” at the White House: A corpus–assisted study of bisociation in conversational laughter–talk. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 24, 371–398. https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.2011.023.

Platt, T., Hofmann, J., Ruch, W., & Proyer, R. T. (2013). Duchenne display responses towards sixteen enjoyable emotions: Individual differences between no and fear of being laughed at. Motivation and Emotion, 37, 776–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-013-9342-9.

Poyatos, F. (1993). Paralanguage: A linguistic and interdisciplinary approach to interactive speech and sounds (Vol. 92). Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., Ali, N. S., Al-Olimat, H. S., Amemiya, T., Adal, T. A., ... & Yeun, E. J. (2009). Breaking ground in cross-cultural research on the fear of being laughed at (gelotophobia): A multi-national study involving 73 countries. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 22: 253–279. https://doi.org/10.1515/HUMR.2009.012

Ritter, M., & Sauter, D. (2017). Telling friend from foe: Listeners are unable to identify in-group and out-group members from heard laughter. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2006. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02006.

Ruch, W. (1990). Die Emotion Erheiterung: Ausdrucksformen und Bedingungen [The emotion of exhilaration: Forms of expression and conditions.] Unpublished habilitation thesis, University of Düsseldorf, Germany.

Ruch, W. (2005). Will the real relationship between facial expression and affective experience please stand up: The case of exhilaration. In P. Ekman & E. L. Rosenberg (Eds.), What the face reveals: Basic and applied studies of spontaneous expression using the facial action coding system (pp. 89–108). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ruch, W., & Ekman, P. (2001). The expressive pattern of laughter. In A. W. Kaszniak (Ed.), Emotion, qualia, and consciousness (pp. 426–443). Tokyo, Japan: Word Scientific Publisher.

Ruch, W., & Wagner, L. (2015). Attributes of laughter: A lexical approach. Zeitschrift für Semiotik, 37(1–2), 109–127.

Ruch, W., Altfreder, O., & Proyer, R. T. (2009). How do gelotophobes interpret laughter in ambiguous situations? An experimental validation of the concept. Humor-International Journal of Humor Research, 22(1–2), 63–89. https://doi.org/10.1515/HUMR.2009.004.

Ruch, W., Hofmann, J., & Platt, T. (2013). Investigating facial features of four types of laughter in historic illustrations. European Journal of Humor Research, 1, 98–118.

Ruch, W., Hofmann, J., Platt, T., & Proyer, R. T. (2014). The state-of-the art in gelotophobia research: A review and some theoretical extensions. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 27, 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2013-0046.

Sauter, D. A., Eisner, F., Ekman, P., & Scott, S. K. (2010). Cross-cultural recognition of basic emotions through nonverbal emotional vocalizations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(6), 2408–2412.

Scherer, K. R., & Ellgring, H. (2007). Are facial expressions of emotion produced by categorical affect programs or dynamically driven by appraisal? Emotion, 7, 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.113.

Van Hooff, J. A. R. A. M. (1972). A comparative approach to the phylogeny of laughter and smiling. In R. A. Hinde, (Ed.), Non–verbal communication (pp. 209–240). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Vettin, J., & Todt, D. (2004). Laughter in conversation; features of occurrence and acoustic structure. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 28, 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JONB.0000023654.73558.72.

Vlahovic, T. A., Roberts, S., & Dunbar, R. (2012). Effects of duration and laughter on subjective happiness within different modes of communication. Journal of Computer–Mediated Communication, 17, 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01584.x.

Walker, G. (2013). Young children's use of laughter after transgressions. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46, 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.810415.

Wildgruber, D., Szameitat, D. P., Ethofer, T., Brück, C., Alter, K., Grodd, W., & Kreifelts, B. (2013). Different types of laughter modulate connectivity within distinct parts of the laughter perception network. PLoS One, 8, e63441. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063441.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the ILHAIRE consortium, Drs. Stephan Schmid (Phonetics Laboratory at the University of Zurich), and Tracey Platt (Department of Psychology, University of Sunderland, United Kingdom) for their expert help, and Bryton Moeller for proofreading.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement n°270780 (ILHAIRE project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruch, W., Wagner, L. & Hofmann, J. A lexical approach to laughter classification: Natural language distinguishes six (classes of) formal characteristics. Curr Psychol 42, 16234–16246 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00369-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00369-9