Abstract

In Alzheimer's disease (AD), attention and executive dysfunction occur early in the disease. However, little is known about the relationship between these disorders and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). This study investigated the relationship between BPSD and attention and execution functions. Twenty-five patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD were included. Neuropsychological tests, mini-mental state examination (MMSE), Raven’s colored progressive materials (RCPM), and trail making test (TMT) were conducted for patients with dementia. The dementia behavior disturbance scale (DBD) was used for psychological and behavioral evaluations of patients with dementia. The AD group showed significantly lower MMSE, DBD, and TMT-B scores than the MCI group. Multiple regression analyses revealed a significant correlation between DBD score, MMSE, and TMT-B.Conclusion: BPSD is associated with cognitive function severity in patients with MCI and early AD, suggesting that attentional and executive functions are independent risk factors for these neural substrates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive disease, and memory impairment is the core symptom of AD. However, it has recently been reported that executive dysfunction is also observed from the very early stages of the disease, even during stages of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Kirova et al., 2015; Salvadori et al., 2019).

Swanberg et al. (2004) indicated that 64% of patients with AD are associated with executive dysfunction, and the degree of executive dysfunction is associated with prognostic factors such as deterioration of cognitive function, psychiatric symptoms, and activities of daily living (ADL). In addition to the core symptoms, the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) have been reported to appear at the MCI stage when cognitive function is preserved (Tsunoda et al., 2020). Presence of BPSD is associated with about 90% of dementias and has been linked to caregiver burden (Sugimoto et al., 2018). In the clinical setting, proper evaluation of BPSD and establishing preventive measures are urgent issues. Bozgeyik et al. (2019) mentioned that the symptoms significantly affecting caregiver burden included delusions, hallucinations, excitement/aggression, depression/discomfort, anxiety, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, and abnormal motor behavior. They also found a correlation between BPSD severity and caregiver depression. They indicated that depression and apathy develop during the early stages, whereas hallucinations, elation/euphoria, and behavioral abnormalities develop during later stages of the disease.

The dementia behavior disturbance scale (DBD), developed by Baumgarten et al. (1990), is one of the available evaluation methods of BPSD in patients with dementia, and it is widely used in clinical practice because the DBD for BPSD is based on simple behavior observation. Kimura et al. (2019) examined the association between nutritional status and BPSD using DBD. They found that early AD with malnutrition showed higher DBD scores and nutritional status was significantly associated with specific BPSD, including verbal aggression/emotional disinhibition and apathy/memory impairment.

In extensive scale survey of patients with AD, a correlation was observed between BPSD and mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores suggesting a relationship between BPSD and cognitive function (Fernández et al., 2010; Majer et al., 2019). However, van der Linde et al. (2016) indicated that previous studies on the association between BPSD and cognitive function did not have a uniform methodology. Furthermore, many reports have used the MMSE as an indicator of cognitive function, and it would be no exaggeration to say that there is bias in the interpretation of the results in terms of the subjects evaluated for cognitive function and specificity. In short, it is unclear precisely what cognitive functions are associated with BPSD, but examining the relationship between BPSD and attention and performance function may help to elucidate the neuropsychological basis of BPSD.

The trail making test (TMT), developed by Reitan and Wolfson (1994), is one of the simple executive function tests widely used in the clinical setting. TMT is a test that reflects visual retrieval, scanning, information processing speed, mental flexibility, and executive function. Recent reports indicate that TMT is a useful tool for predicting the transition from MCI to AD (Cajanus et al., 2019). In this study, we investigated the relationship between BPSD and attention and executive function in patients with MCI and AD based on TMT and DBD scores.

Methods

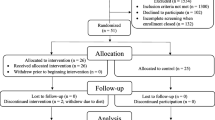

Subjects

The subjects were 60 patients who visited a specialized outpatient clinic for dementia during the study period. In addition to the neurological examination, subjects underwent neuroradiological examinations such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography of the brain and blood biochemical examination. Additionally, patients were examined by a specialist. MCI and AD were diagnosed based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Patients were excluded from this study if they had a history of cerebrovascular disease; psychiatric disorders and delirium; and a diagnosis of dementia. Those who had difficulty in carrying out the tasks involved in this study were also excluded from the study.

This study was approved by the ethics review committee of Kawasaki Medical and Welfare University (Approval No. 18–109). Study procedures were conducted after these were explained to the patients and their families in writing and the informed consent was obtained.

Assessment of Cognitive Function

The final study population was 25 patients (9 men and 16 women) with a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 83.2 (6.01) years. Of these, 12 had MCI and 13 had AD.

All patients underwent MMSE, Raven’s Colored Progressive Materials (RCPM), and TMT. As a standard, we assessed Part A of TMT and Part B of TMT, according to the TMT-Japan (Japan Society for Higher Brain Dysfunction Brain function test committee, 2019).

Assessment of BPSD

DBD was used for the evaluation of BPSD. The DBD consists of 28 questions on behavioral abnormalities observed in patients with dementia, including wandering, agitation, eating disorders, aggression, and sexual abnormalities. The main caregiver conducts observation and evaluation, and each item is scored in 5 grades: “none” (0 points), “rarely” (1 point), “sometimes” (2 points), “sometimes” (3 points), and “always (4 points).” The total points were calculated (maximum 112 points). A higher score indicated higher frequency of various behavioral abnormalities lower score indicated lower frequency.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analysis was performed on the time taken for TMT-part A and TMT-Part B, the RCPM score, and the relationship between MMSE score and DBD score. Continuous variables were reported as medians (25th, 75th percentiles; IQR) for non-parametric data. The chi-squared and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to examine the differences between the MCI and AD groups. Moreover, the examination items for which the significance level of the correlation was p < 0.05 were introduced into three different models, and a multivariate analysis was carried out. The significance level of multivariate analysis was two-sided p-value < 0.01. JMP 11 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Patient Background of All Cases

Patient characteristics and neuropsychological test results for all cases are shown in Table 1. The number of subjects by CDR level were CDR 0.5 = 12, CDR1 = 7, and CDR2 = 6. The mean (SD) MMSE score was 22.8 (4.64). The mean (SD) RCPM was 22.4 (5.67). The mean (SD) task execution time in TMT was 105.6 (52.87) seconds on average for TMT-A and 307.8 (169.54) seconds on average for TMT-B. The mean (SD) DBD score of the study subjects was 19.52 (11.06).

Comparison of Tests in the MCI and AD Groups

Patient characteristics and neuropsychological test results for the MCI and AD groups are presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences in sample size and age. The MMSE score was significantly lower in the AD group than in the older persons group (p < 0.01). In the TMT group, the AD group showed a significant decrease in TMT-B compared with the MCI group (p < 0.01).

Percentage of DBD Occurrence by Category

Figures 1, 2 show the percentage of DBD incidence by item in the MCI and AD groups. Of the DBD scores, this study rated Sometimes, Frequently, and All the time as “Symptomatic.” The highest incidence in the MCI group was 66.7% for “Ask the same question over and over again,” 41.7% for “Sleeps Successfully During the Day,” and 41.7% for “Shows lack of interest in daily activities.” In the AD group, 58.3% had “Shows lack of interest in daily activities,” 55.6% had “Ask the same question over and over again,” and 52.8% had “Sleeps Successfully During the Day.”

Multivariate Analysis of DBD Scores and Neuropsychological Tests

Table 3 shows the factors affecting DBD scores according to the three different models of independent variables. In Model 1, the MMSE score, TMT-A, and TMT-B were selected as independent variables. In Model 2, MMSE was replaced by RCPM, and in Model 3, multivariate analysis was performed on variables including all factors. As a result, the DBD score was found to be associated with the MMSE score and TMT-B.

Discussion

Relationship Between DBD Score and Severity of Dementia

The DBD was designed to evaluate the behavior abnormalities recognized during ADL. Although the main disadvantage of the DBD is that it does not include psychiatric symptoms among the evaluation items, its main advantage is that the caregiver can easily complete the DBD. Accordingly, the examiner can infer issues related to the nursing burden and connect the patient with high-quality dementia care. Baumgarten et al. (1990) reported that the internal consistency of the DBD was 0.84, and the correlation coefficient of retest performed at 2-week intervals was 0.71, showing sufficient reliability. Additionally, the DBD score was related to the severity of dementia.

In this study, there was also a negative correlation between DBD score and MMSE, and BPSD tended to increase with the severity of cognitive function. The MMSE is a screening test covering cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and executive function. The strong relationship between the MMSE score and the DBD score indicates that there is a relationship between the severity of dementia and BPSD as described above.

On the other hand, there was no significant relationship between RCPM and DBD scores.

Ambra et al. (2016) investigated RCPM of MCI and AD and found that visual space and problem-solving dysfunctions that bound the progression from amnestic MCI to dementia were all cognitive dimensions explored by RCPM; therefore, suggesting that it does not affect to the same extent. The reason for the lack of association between the RCPM and the DBD score in this study may be that most of the subjects were able to live at home, and their intellectual function was relatively preserved.

Kazui et al. (2016) investigated BPSD according to four types of dementia: AD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and vascular dementia (VaD) using the neuropsychiatric inventory, which includes the evaluation items of psychiatric symptoms. The results showed that neuropsychiatric inventory was also associated with dementia severity. Besides, the rate of apathy was high in all dementia types. Apathy is defined as a lack of motivation, and apathy is differentiated from depression by the absence of emotional distress or any other distress. BPSD occur especially in the early stages of dementia, ranging from 36 to 88% in AD (Chow et al., 2009a, 2009b; Starkstein et al., 2006), and from 15% to 36.2% in MCI (Geda et al., 2008; Palmer et al., 2007). In addition to the items related to memory impairment, the prevalence of symptoms related to apathy (i.e., “Sleeps Successfully During the Day” and “Shows lack of interest in daily activities”) was higher in the MCI and AD groups. Additionally, the occurrence of BPSD in the AD group in this study was similar to that in the MCI group, because the AD group in this study had mild to moderate CDR and many patients had early-stage disease. These results suggest that there is a relationship between the severity of dementia and the severity of BPSD in patients with MCI and early AD, especially concerning apathy.

Relationship Between DBD Score and TMT

In this study, we investigated the relationship between DBD and MMSE, RCPM, and TMT, which are often used in screening tests for dementia. The AD group had lower MMSE and TMT-B than the MCI group. Further, the relationship with the DBD score was examined from the analysis of three multiple regression models. However, both TMT-B levels were significantly lower in the AD group than in the MCI group. Sanchez-Cubillo et al. (2009) state that TMT-A relies heavily on visual search speed, TMT-B relies heavily on working memory and information manipulation related to task switching, and that TMT-B in particular reflects performance features. In this study, DBD scores were more strongly correlated with TMT-B than with TMT-A. Additionally, behavioral abnormalities judged as apathy accounted for the majority of the BPSD presented by the patients, suggesting that executive dysfunction may be an independent risk factor for BPSD. Robert et al. (2006) reported that although the results of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding test, a memory assessment, and the Stroop Color Interference Task, a free recall assessment and an assessment of inhibitory function, were decreased in MCI, there was no significant difference between TMT-A and TMT-B, and there was no relationship between apathy and frontal lobe function. The differences between the results of this study and those of Robert et al. (2006) may be associated with the younger age and higher MMSE scores of their patients (Lezak et al., 2004). Therefore, a simple frontal function test like TMT may not have detected the disorder. However, the relationship between DBD score and TMT-B was shown in this study. TMT-B is based on the ability of attention transfer among performing functions, and in this study, it is limited to describing the relationship between BPSD, including apathy and performing functions. Further detailed examination including other evaluation methods is necessary.

The deterioration of BPSD in the nursing field not only lowers the QOL of the patient but also increases the pain of the patient, and the appropriate evaluation and the execution of the preventive measures are required. However, for many older patients with dementia, such as the subjects of this study, evaluation by a standardized test battery is difficult because of the deterioration of sensory and motor functions and problems with the duration of attention. Based on the results of this study, we believe that it is essential to evaluate BPSD not only by behavioral assessment but also by comprehensive assessment using neuropsychological tests that can be easily performed, so that appropriate symptoms can be grasped and effective care can be planned.

The main limitations of this study were that the number of subjects was small and the cases were limited to MCI and AD. As not all subtypes of dementia were included, the results cannot be generalized to other dementia types. Earlier studies also reported that initial BPSD was more prominent in DLB than in AD (Chow et al., 2009a, 2009b). Therefore, a larger number of cases and the inclusion of patients with all types of dementia are needed to conduct other studies.

Conclusion

In patients with MCI and early AD, the DBD score was associated with the severity of cognitive function, suggesting that BPSD tends to become more severe with the severity of dementia. The TMT is a simple test of attention and executive function, and the TMT-B was correlated with the DBD score, suggesting that executive dysfunction may be an independent risk factor for BPSD.

References

Ambra, F. I., Iavarone, A., Ronga, B., Chieffi, S., Carnevale, G., Iaccarino, L., et al. (2016). Qualitative patterns at Raven’s colored progressive matrices in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(3), 561–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-015-0438-9

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Baumgarten, M., Becker, R., & Gauthier, S. (1990). Validity and reliability of the dementia behavior disturbance scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 38(3), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03495.x

Bozgeyik, G., Ipekcioglu, D., Yazar, M. S., & Ilnem, M. C. (2019). Behavioural and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease associated with caregiver burden and depression. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(4), 656–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2018.1541646

Cajanus, A., Solje, E., Koikkalainen, J., Lötjönen, J., Suhonen, N. M., Hallikainen, I., et al. (2019). The association between distinct frontal brain volumes and behavioral symptoms in mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and frontotemporal dementia. Frontiers in Neurology, 10, 1059. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01059

Chow, T. W., Binns, M. A., Cummings, J. L., Lam, I., Black, S. E., Miller, B. L., et al. (2009). Apathy Symptom Profile and Behavioral Associations in Frontotemporal Dementia vs Dementia of Alzheimer Type. Archives of Neurology, 66(7), 888–893. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/797519

Chow, T. W., Binns, M. A., Cummings, J. L., Lam, I., Black, S. E., Miller, B. L., et al. (2009b). Apathy symptom profile and behavioral associations in frontotemporal dementia vs. Alzheimer’s Disease. Archives of Neurology, 66(7), 888–893. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2009.92

Fernández, M., Gobartt, A. L., Balañá, M., COOPERA Study Group. (2010). Behavioural symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their association with cognitive impairment. BMC Neurology, 10(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-10-87

Geda, Y. E., Roberts, R. O., Knopman, D. S., Petersen, R. C., Christianson, T. J., Pankratz, V. S., et al. (2008). Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and normal cognitive aging: Population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(10), 1193–1198. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1193

Japan Society for Higher Brain Dysfunction, Brain function test committee. (2019). Trail Making Test, Japanese edition (TMT-J). Shinkoh Igaku Shuppansha Co., Ltd.

Kazui, H., Yoshiyama, K., Kanemoto, H., Suzuki, Y., Sato, S., Hashimoto, M., et al. (2016). Differences of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in disease severity in four major dementias. PLoS ONE, 11(8), e0161092. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161092

Kimura, A., Sugimoto, T., Kitamori, K., Saji, N., Niida, S., Toba, K., & Sakurai, T. (2019). Malnutrition is associated with behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia in older women with mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients, 11(8), 1951. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081951

Kirova, A. M., Bays, R. B., & Lagalwar, S. (2015). Working memory and executive function decline across normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. BioMed Research International, 2015, 748212. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/748212

Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Loring, D. W., & Fischer, J. S. (2004). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press.

Majer, R., Simon, V., Csiba, L., Kardos, L., Frecska, E., & Hortobágyi, T. (2019). Behavioural and psychological symptoms in neurocognitive disorders: Specific patterns in dementia subtypes. Open Medicine, 14(1), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2019-0028

Palmer, K., Berger, A. K., Monastero, R., Winblad, B., Bäckman, L., & Fratiglioni, L. (2007). Predictors of progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 68(19), 1596–1602. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000260968.92345.3f

Reitan, R. M., & Wolfson, D. (1994). A selective and critical review of neuropsychological deficits and the frontal lobes. Neuropsychology Review, 4(3), 161–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01874891

Robert, P. H., Berr, C., Volteau, M., Bertogliati, C., Benoit, M., Mahieux, F., et al. (2006). Neuropsychological performance in mild cognitive impairment with and without apathy. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 21(3), 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1159/000090766

Salvadori, E., Dieci, F., Caffarra, P., & Pantoni, L. (2019). Qualitative evaluation of the immediate copy of the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure: Comparison between vascular and degenerative MCI patients. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 34(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acy010

Starkstein, S. E., Jorge, R., Mizrahi, R., & Robinson, R. G. (2006). A prospective longitudinal study of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 77(1), 8–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2005.069575

Sugimoto, T., Ono, R., Kimura, A., Saji, N., Niida, S., Toba, K., & Sakurai, T. (2018). Physical frailty correlates with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(6). https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17m11991

Swanberg, M. M., Tractenberg, R. E., Mohs, R., Thal, L. J., & Cummings, J. L. (2004). Executive dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology, 61(4), 556–560. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.61.4.556

Sánchez-Cubillo, I., Periáñez, J. A., Adrover-Roig, D., Rodríguez-Sánchez, J. M., Rios-Lago, M., Tirapu, J. E. E. A., & Barcelo, F. (2009). Construct validity of the Trail Making Test: Role of task-switching, working memory, inhibition/interference control, and visuomotor abilities. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS, 15(3), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617709090626

Tsunoda, K., Yamashita, T., Osakada, Y., Sasaki, R., Tadokoro, K., et al. (2020). Early emergence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in cognitively normal subjects and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 73(1), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190669

van der Linde, R. M., Dening, T., Stephan, B. C., Prina, A. M., Evans, E., & Brayne, C. (2016). Longitudinal course of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(5), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.148403

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19 K 19782.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Atsushi Toda and Shinsuke Nagami designed the protocol and analyzed the data of the manuscript. Ayako Katsumata collected the data collection and reviewed the manuscript. Shinya Fukunaga reviewed the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Atsushi Toda and all authors provided feedback on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to Participate

All participants and their families were explained the study and they provided written informed consent.

Consent for Publication

The subjects were explained that the data was anonymized and that the individuals were not identified in the study. It was also explained that the data of the subjects who consented would be used for presentations at academic conferences and research papers and not be used for other purposes. The data of subjects who did not consent to participate or who withdrew their consent was not used.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in agreement with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

This study was approved by the ethics review committee of Kawasaki Medical and Welfare University (Approval No: 18 -109).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Toda, A., Nagami, S., Katsumata, A. et al. Verification of Trail Making Test in Elderly People with Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Ageing Int 47, 491–502 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-021-09424-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-021-09424-y