Abstract

This pilot study analyzes interview research with long-term residential care nursing staff in four Canadian provinces, revealing relationships between workers’ psychological health and well-being and working conditions that include work overload, low worker control, disrespect and discrimination. Further, individual workers are often required to cope with these working conditions on their own. The findings suggest that these psychological health and safety hazards can be addressed by both individual workplaces and government regulation, but are currently ignored or mis-recognized by many employers and even by workers themselves. These findings indicate opportunities for improving psychological health and safety in long-term residential care work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

[W]e’re told ‘Suck it up. It’s your job.’ And that’s so frustrating because that’s not my job. It’s not my job to come to work and expect to be punched in the face. You know, it’s not my job to come to work and expect to be hurt because you didn’t staff the building properly so now I can’t take care of my own family. You know what I mean? (CCA, Manitoba)

The evidence is mounting: increasingly difficult working conditions in long-term residential care homes in Canada are producing high rates of care worker injury, turnover and stress (Armstrong 2004, Yassi and Hancock 2005, Armstrong et al. 2011, Daly and Szebehely 2011, Banerjee et al. 2012, Astrakianakis et al. 2014, Banerjee et al. 2015). Yet, we know very little about these workers’ psychological well-being, how they deal with psychological health and safety hazards at work and how psychological stress affects their personal lives. Long-term residential direct care staff includes registered nurses (RN), licenced practical nurses (LPN),Footnote 1 social workers and continuing care aides (CCA).Footnote 2 These workers experience time-pressures and heavy physical and emotional demands as well as violence, leading to high rates of injury and disability (Statistics Canada 2012). Further, these factors are associated with staff turnover, recruitment and work absence, which have been identified as a key management issues in the long-term care sector (Andersen 2009, Chu et al. 2014, Squires et al. 2015, Pijl-Zieber et al. 2016).

In this article, we report findings from a pilot study using interview data collected in eight Canadian long-term care homes – two each in British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario and Nova Scotia – to explore direct care workers’ experiences and perspectives related to psychological health and safety.

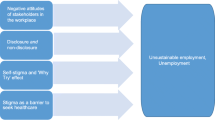

This pilot study identifies four areas requiring further research, policy and practice attention. First, the toll on emotional wellbeing exacted by long-term residential care work is often going unidentified and unaddressed by employers and regulators as an occupational health and safety issue, often leaving workers to cope on their own. Second, care workers’ psychological health and safety hazards include work overload, racism and sexism in the workplace – hazards that can be prevented. Third, workers’ coping on their own is, in and of itself, a workplace psychological health hazard, shaping conditions of work that erode workers’ abilities to feel, respond and enjoy life, both at work and at home.

Finally, findings from our pilot study suggest that while working conditions are determined at the policy level as well as by owners and managers, long-term care homes are not equal in terms of the psychological hazards at work. Some appear to be more positive workplaces with reduced levels of psychological health hazards, but these workplaces are also constrained by their jurisdictionally specific funding and regulatory regimes. These findings suggest directions for research, policy and practice that have potential to improve psychological health and safety in long-term residential care work.

Addressing Psychological Health and Safety: A Policy and Practice Gap

Unlike other countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Australia, Spain and France, Canadian workplaces are not required by law to protect workers’ psychological health and safety. The Canada Labour Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. L-2) requires workplace policies to prevent and address occupational violence and sexual harassment. However, responsibility for occupational health and safety law is at the provincial and territorial levels, with the result that there are fourteen different laws across the country. In 2013, Canada introduced a voluntary National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace (Government of Canada 2013) that includes consideration of job-related stress, overwork and respect. The standard does not identify hazards but rather specifies conditions of work under which psychological health hazards may be prevented or addressed.

Long-term residential care workplaces in Canada comply with provincial and territorial standards by implementing policies on violence and harassment, but to date, long term care homes’ health and safety policies have not addressed psychological harm as laid out in the voluntary National Standards. Long-term care should not be considered exceptional in this omission, as progress on policy that addresses mental health at work has been slow and uneven in Canada, despite a variety of reports, commissions and consultations (Kaiser 2009). In many provinces, workplace policies to address bullying and harassment have been added or strengthened (Health Employers Association of British Columbia 2014). However, most initiatives treat mental health issues as either problems workers bring with them into the workplace or problems related to individual behaviour and relationships. They are seldom perceived as problems related to working conditions and almost never understood as a reflection of wide-spread social inequalities related to gender, race, class and immigration status embedded in working conditions.

Long-term care workplace health and safety policies and training tend to ignore psychological health and safety and focus on hazards related to musculoskeletal injuries, infectious diseases and, more recently, violence (Ontario Health and Safety Association 2010, Health Employers Association of British Columbia). This is likely associated with system-wide interests to reduce the costs of disability claims associated with these factors (March et al. 2014).

Workplaces tend to deal with workers’ mental health issues through what LaMontagne et al. (2014) describe as secondary or ameliorative interventions which aim to improve workers’ coping, and/or tertiary interventions that support rehabilitation after injury (p.133). Most employers rely upon employee assistance programs that include individual counselling or psychological services (Page et al. 2013). These policies do nothing to address primary prevention, aimed at “reducing workplace stressors at their source” (ibid), although systematic reviews have shown repeatedly that these measures are the most effective interventions (Egan et al. 2007, Martin et al. 2009, Tan et al. 2014).

Recent research on workplace mental health points to the convergence of factors that produce mental health, with workplace factors such as job insecurity, low social support at work, harassment, effort-reward imbalances and unfair treatment playing important roles (Stansfeld and Candy 2006, Bonde 2008, LaMontagne et al. 2010, Szeto and Dobson 2013). This research supports earlier theorizations of the relationship between work organization and health (Karasek and Theorell 1992). However, how and whether workplace mental health intersects with factors related to gender and race remain under-investigated (Messing 1997, Armstrong 2012, Rosenfield 2012).

Further, long-term care workers’ mental health continues to be treated as an individual issue and responsibility in much of the occupational health and safety information affecting them, despite research findings that demonstrate the significance of health care and long-term care working conditions in shaping care workers’ psychological health (Muntaner et al. 2006, Sabo 2006, Rai 2010, Sabo 2011). For example, the website of the Public Services Health and Safety Association in Ontario suggests yoga, taking breaks and seeing a mental health professional as ways to promote worker mental health (Public Services Health and Safety Association 2016). Another example is from a community-based research project that developed personal support worker “competencies” for palliative care. Its competencies include dealing with psychological health issues such as grief and compassion fatigue under the category “self-care” (Quality Palliative Care in Long Term Care Alliance 2012).

To summarize, psychological health and safety concerns in long-term care work tend to be either minimized or framed as individual problems that require workers, rather than workplaces, to change. Our findings point to factors not included in the literature noted above, while also supporting many of these research conclusions. In what follows, we briefly review our research methods. Next, we describe our research findings that reveal workers’ accounts of psychological hazards at work, including hazards associated with the intrinsic nature of long-term care work, who does it and the issues of work overload, sexism and racism. We discuss workers’ responses to these hazards and how they internalize and cope with the individualization of responsibility. In the final section, we discuss some differences in accounts of psychological hazards between residences, suggesting that facility-based working conditions can reduce these psychological hazards in some but not all ways.

The Study

This pilot study was the result of our growing awareness of the need for attention to psychological health and safety hazards in long-term care work. When reviewing Canadian interview transcripts from a large-scale international comparative study that seeks to identify promising practices in long-term care homes, care workers’ expressions of moral distress, work overload and emotional and physical exhaustion jumped off the interview transcript pages. These comments were particularly shocking because this promising practices research had been conducted in long-term care homes recognized for their excellence.

This large-scale research study was conducted by an international, interdisciplinary team of co-investigators and graduate students that completed a series of comparative “rapid ethnographies” (Baines and Cunningham 2011) and short, one day “flash ethnographies” in a total of 27 long-term care homes in six countries, including more than 500 interviews. Informed by the larger project, this analysis draws on the Canadian portions of this international data set. We analyzed interviews conducted with Canadian nursing and social work staff conducted in eight long-term care homes,Footnote 3 located in four provinces in Canada. These interviews were conducted with 20 Registered Nurses (RN), 20 Licensed Practical Nurses (LPN), 44 Continuing Care Aides (CCA) and 3 social workers. The interviews, which were on average an hour long, were transcribed verbatim. The semi-structured interview guides used for these interviews did not have specific questions about emotional and physical exhaustion, health and safety, burnout, racism or sexism.

This pilot study proceeded as follows. The first author, who was a team member at four of these eight Canadian ethnographies as well as in the United States, the United Kingdom and Sweden, first reviewed these transcripts and coded the interviews with attention to work organization, approach to care, gender and racialization. Emotional exhaustion emerged as an unanticipated but robust theme worthy of further analysis. A review of the literature pertinent to nursing work, compassion fatigue, burnout and mental health, together with the extensive professional clinical mental health backgrounds of the first and third authors, sensitized us to potential themes and considerations for our analysis. The interviews were then entered in NVivo 10 by the second and third authors and analyzed using a general inductive approach (Thomas 2006). Transcripts were read several times before coding line by line, formulating and then re-formulating categories and themes. The first author then re-coded the data using the developed categories and themes, in order to ensure coding consistency and clarity. The analysis of the data was completed by the first three authors. The findings were then reviewed by the principal investigator and fourth author, who was involved in all of the site visits included in this analysis.

Long-term care workers’ psychological health and safety is affected by both intrinsic and extrinsic challenges involved in working with older, frail, vulnerable and dying populations. At all of the sites included in this research, long-term care nursing work was intrinsically difficult. These care aides and nurses attended to the needs of frail and acutely ill people who were often in the last months of their lives. Most of their residents were experiencing some combination of dementia, disability, illness and incontinence that had brought them to residential care. From the perspectives of these workers, this vulnerable population required attentive, careful support that went beyond meeting their medical and bodily care needs and included their need for human interaction and meaningful activity. Further, residents’ families also brought particular challenges and demands for attention and care.

These challenges are not necessarily hazardous. Indeed, studies have shown that workers receive psychological benefits from providing care, including satisfaction from the relationships of care as well as from their material contributions to residents’ comfort and well-being in late life (Armstrong 2004, Slocum-Gori et al. 2013). We heard about this satisfaction in many interviews.

I enjoy my job. I enjoy the satisfaction that I get that a resident is happy, [a] smile on their face when they know I’m coming back the next day. (CCA Nova Scotia)

However, like workers across the sector (Marcella and Kelley 2015), respondents across all sites described challenges related to higher resident acuity and more frequent deaths. These circumstances are due to government policies that ensure people enter residential care only when they have become acutely ill or very disabled. This can create strain for workers, as they watch residents’ health deteriorate or deal with residents’ anger and aggression, as our respondents pointed out repeatedly.

I work with patients who are a lot sicker all day. I had more satisfaction when I was working in palliative when I saw people dying all the time. (LPN, Ontario)

It’s very hard on the mind dealing with dementia, getting beat up every day. (CCA Nova Scotia)

Experiencing many resident deaths can be a psychological health hazard, as one RN told us:

A cluster of five or six deaths and the staff are all walking around with their heads down and, you know, you’ve got to do some grief work. (RN Manitoba)

But workers reported that their own grief and mourning was not the most challenging aspect of dealing with death experiences. Our respondents told us that the challenges involved in responding to family members’ grief were more difficult.

Because I went deep, deep with a family, you know, with their daughter and she even asked me to [be] the one to carry the coffin. I said never again. Never again. It was too hard” (CCA Ontario)

A gentleman passed away… and his wife was very upset that he had passed away… it doesn’t bother me. I don’t mean this in a mean way but it doesn’t bother me when they pass away because he was 91 years old and he’s at peace and he had Alzheimers’. But you couldn’t console her at all and it was really hard. I found that very stressful. (CCA Nova Scotia)

In addition to continually witnessing suffering, death and grief, long-term residential care work is shift work, which can create other psychological hazards. While working shifts is not always directly hazardous to health, it shapes stresses related to sleeping, eating and exercise and poses challenges to ensuring child care, spousal relationships, social participation and performing domestic work (Vogel et al. 2012, Matheson et al. 2014). As most long-term care workers are women, they are more likely than men to have domestic and familial responsibilities that are affected by shift work. In this study, workers described these issues as difficult and tiring, but they did not indicate that working shifts contributed to an intolerable or problematic level of psychological stress. However, shift work challenges are part of most care workers’ lives, and are likely to influence their psychological well-being, as a CCA in one home explained.

My schedule is full time day and evenings so it depends. You have a nine week rotation. We have six [days], we have five. Five is okay. Six is very, very tiring. For me it’s a killer. But I have to make sure I rest before six or after five because it’s very, very tiring. And then we have two days off. And … I don’t know how many months you get two days off … That’s how it works. We don’t get every weekend off. It takes two months before I get a weekend off. It’s hard. (CCA British Columbia)

These intrinsic challenges of long-term care work were compounded by extrinsic work organization factors, which combined to undermine workers’ psychological health and well-being. These extrinsic factors were work overload and low worker control. The ubiquity of these problematic working conditions have been well documented in the Canadian residential care research literature (Armstrong 2004, Armstrong et al. 2009, Daly et al. 2011, Daly and Szebehely 2011, Banerjee et al. 2012, Armstrong 2013a, Armstrong 2013b, Banerjee et al. 2015), and are supported by our findings.

Long-term care work overload refers to a combination of time pressures, task difficulties and interpersonal demands. Work overload in caring occupations has a different impact on workers than work overload in workplaces that do not involve caring. When long-term care workers do not have time to do their work fully and well, they are forced to live with the knowledge that residents often suffer, and this knowledge produces continual feelings of frustration, guilt, anger and sadness for many workers. Further, care requires some trust and relationship between those who care and those who are cared for. Being unavailable to respond to a residents’ needs undermines these relationships, making care more difficult. These issues were primary concerns for workers, and a source of significant psychological strain. Among the complaints regarding working conditions, the strongest finding was that workers had insufficient time to attend to residents’ comfort and loneliness.

[W]e’re so limited in our time with all the appointments, activity. It’s like [snapping fingers] go, go, go, go, go, you know. And it’s sad. It’s the worst thing that can happen to you is to get old and to come into a nursing home. That’s what I think. (CCA Ontario)

These kinds of working conditions have been shown to affect health care workers’ mental health (Armstrong and Jansen 2015). Like other health care workers who are mostly women and who work in feminized work environments, long-term care workers lose among the most days of work per worker to illness of any other occupational category in Canada (Daboussy and Uppal 2012). The research literature reveals high rates of mental health problems among health care workers, including conditions associated with psychological health and safety such as compassion fatigue and burnout among the most common conditions (Bourbonnais et al. 1998, Pereira et al. 2011, Ray et al. 2013, Slocum-Gori et al. 2013). Nurses in Canada show twice the rate of depression when compared to all Canadian working women, and low job autonomy, working outside of hospitals and job strain were significant correlated factors (Enns et al. 2015). These studies indicate that these health issues have led many workers to exit the health care sector, while chronic absenteeism, presenteeism (working sick), substance abuse, cynicism and significant amounts of unpaid overtime have been documented, further indicating significant job strain.

In our research, these findings were supported by the accounts provided by these direct care workers. Nursing staff in all of our site ethnographies told us that resident care was intrinsically challenging work, but psychological health and safety hazards were associated with having too much to do, too little time to attend to resident needs and too many very heavy, challenging tasks, without autonomy to decide when and how best to do them.

They told us that exhaustion and burnout intensified working conditions where there was already too much to do, due to regular staff absences taken by workers to recover from exhaustion. This contributed to a cycle of work overload, burnout and absences from work.

Okay, well we’re short two CCAs and one LPN and…we as nurses care for two houses, you know, we care for all these people with only three [staff]. . . We need more CCAs in my opinion too . . . only three CCAs, everyone is exhausted, you know. Like I said it’s not so much the job, it’s knowing that okay, if I go to work today what’s going to happen? Am I going to be short? Because if I had a fall right now - if someone fell right now - I wouldn’t be able to take care of them. There’s just nobody to help and there’s nobody to cover, right? So you just basically go through a shift hoping you’re going to have a good shift and nothing big happens because if it does, I mean you have to deal with it. But there’s nurses here that go without breaks because you just don’t have the time. A lot of nurses go without breaks and that’s again cause for burnout, right? (LPN Nova Scotia)

Further, in these sites, we were told that this pattern of exhaustion- short staffing- exhaustion meant that it was hard to backfill staff absences.

It’s paid overtime and once again sometimes people are so overworked they don’t even want the overtime. They say ‘I’m just too tired. I don’t want it.’ Then you end up working short which doesn’t help the situation at all either. We can’t get anybody, you’re working short, so you try the best you can. (CCA Ontario)

Work overload was intensified further in workplaces where managers required workers to complete their work within regular hours, and would not pay overtime in order for regular duties to be completed, thus giving workers the choice between ignoring resident needs or putting in unpaid overtime. In our interviews, many workers told us that they chose unpaid overtime.

We had our staff saying that they’re really struggling getting all that work done and so then the message becomes about ‘You have to get it done and no overtime will be issued.’ And so that’s a real challenge because then your staff are staying for overtime and not being compensated for it. (RN Nova Scotia)

Worker’s abilities to plan and execute their work were sometimes complicated by requirements to comply with directives that aimed to offer more autonomy to residents. At the same time, workers themselves had little control over how and when they performed their work tasks. While resident autonomy is a promising practice, without sufficient staffing and matching staff autonomy to meet resident preferences, workers, like the CCA quoted below, experienced continual challenges.

I think it’s a lot here is they’re trying to give them [residents] more and more control and so as a worker it makes it harder for us because they want us to have them up and washed and in the dining room by a set time and whatever. But giving that choice to the resident [creates problems]. Like for example my gentleman yesterday normally wants up at nine. He wanted up at ten so I left him and he’s ringing at ten to ten. He wants to get up now and I’m in the middle of a bath. So it kind of makes it hard that way. (CCA Ontario)

Across jurisdictions and workplaces, the results of this work overload and low worker control were clear. These workers, as a group, are tired out to the point of exhaustion and depletion. The impact on their personal lives was a common issue.

Interviewee: Me, I’m having a hard time. Like I’m driving with my husband at this time of the year. . . I arrive home. I undress. And he cook and I wake up when he’s calling me for supper. And I go deep sleep.

Interviewer: So that’s pretty tiring.

Interviewee: Tiring!

Interviewer: Yeah, that’s an impact.

Interviewee; On my life. I’ve got no life. You got no life. Don’t plan on going shopping or whatever. You don’t have the strength. Your legs don’t want to go anymore. [laughter].

(CCA Ontario)

A further issue for some workers was job insecurity, which, despite pressing issues of low staffing, has been an outcome of funding challenges in the long-term residential care sector in Canadian jurisdictions (Torjman 2013, Daly 2015). This job insecurity stress was compounded by workers’ concerns for resident well-being. Workers’ concern for residents, as a compounding factor that intensified other job stresses, was a dominant theme.

For a while where the stress was coming from too like we’re getting cut here, cut there, cut there and everybody is getting frustrated because we’re having to pick up. And we’ll be the first ones to be booted out the door, the ones that are working and trying to pick up and trying to make things better for the residents because ultimately they’re the ones that are going to suffer out of this. Like all the cuts and everything that’s going on right now, they’re the ones that’s going to suffer because they’re not going to get the care that they’re supposed to. They’re going to have bed sores. They’re going to be wet in their diapers. (CCA Ontario)

In our interviews, this moral distress emerged as a clear result of work overload and low worker control. This finding adds to and confirms findings of other researchers who focused only on dementia care (Pijl-Zieber et al. 2016). Moral distress has been conceptualized as:

a painful feeling or psychological imbalance resulting from recognising an ethically correct action that cannot be performed because of hindrances such as lack of time, reluctant supervisors or a power structure that may inhibit a moral, political, institutional or juridical action. (Barlem and Ramos 2015)

Nursing staff’s moral distress at work has been shown to have a negative impact on psychological and physiological wellbeing and is also associated with worker’s intentions to quit their jobs and the field of long-term care (Piers et al. 2012, McGilton et al. 2014). In our interviews, workers made links between feelings of moral distress due to ethical dilemmas and their own psychological health at home and at work.

But we’re human. And say an incident happens with a resident and of course I don’t sleep at night because that’s in my head. Like they say “Leave it here”, but that’s easy to say but its not easy to do. (CCA Ontario)

One Manitoba RN put it succinctly; “So because we care about the people we take care of we’re our own worst enemy”.

Disrespect and Discrimination

Another key psychological health and safety hazard is disrespect, including workers’ experiences of sexism and racism. The long-term residential care work labour force in Canada, like that in many industrialized countries, is changing (Fujisawa and Colombo 2009). We know that while the vast majority of these workers are women, more direct care staff are new immigrants, from visible minority groups and/or are men (Laxer 2013). At the same time, this labour force remains older, with almost half of the workers between 45 and 69 years of age (Laxer 2013).

Long-term residential care work is feminized and devalued work. Feminized work is work in which the norms, values, pay and working conditions suffer due to social assumptions that women’s “natural” abilities, family roles and subordinated place in society make them ideal for this work, which is usually considered unskilled or low skilled. The pay rate and status of these jobs is low (Braedley 2013, Braedley and Martel 2015). Gender remains under-considered as a factor in both occupational health (Messing 1998, Messing 2005, Messing and Mager Stellman 2006, Artazcoz et al. 2007, Braedley 2009, Messing and Silverstein 2009) and mental health research (Oliffe and Phillips 2008, Oliffe and Han 2014). The relationship between gender and psychological health and safety is under-researched and under-theorized (International Labour Organization 2013).

Long-term care work can also be described as increasingly racialized, not only by the growing proportion of visible minority people who do it, but by social norms that suggest these people do this work because it is “natural” or “culturally appropriate” for them to do so. For example, several respondents told us that people from the Philippines were particularly well-suited to caring due to their cultural respect and treatment of the elderly. Paid domestic work has been racialized work in some regions of Canada for a long time, relying on indigenous women and immigrant women from racialized groups (Bakan and Stasiulis 1997). The increasing racialization of long-term care work in Canada is arguably an extension of these long standing domestic arrangements, which have roots in racist ideologies (Glenn 1992, Glenn 2010). Further, although men are now entering long-term care work in larger numbers, a significant proportion of these men are from immigrant and racialized communities.

In our ethnographies in urban centres, the gender/race dynamic was that “the majority of the staff have dark skin and the majority of the residents have light”, as one respondent put it. In the everyday interactions amongst and between staff, residents, families and others, what appeared to our research team as blatant racism and sexism was often minimized or understood by staff as only “cultural”. What was particularly notable about these situations, however, was that workers dealt with these circumstances on their own in most cases, enduring these experiences as an unchangeable and unchallengeable condition of work, as for example, in cases of sexual harassment by residents.

The first time I was in the dining room we have one particular male patient. All the staff was feeding in the dining room and then he grabbed me like that. I was so upset and shy. I know I have a big bum. I was like, oh, I was melt inside myself . . . So I went . . . I didn’t come for a while but I never go and complain because I was ashamed of myself. And then after when I come back I hear he does this to other people. I said “ohhh”. (RPN Ontario black woman)Footnote 4

Typically, workers expected to be blamed for these experiences. Their underlying perception was that dementia, old age and other illness prevented residents from self-regulating. Workers were expected to prevent these circumstances.

I had a resident grab me in a sexual manner. If you say anything at all the response is “What did you do?” “It’s in your approach.” (LPN Nova Scotia, white woman)

Racism was often perceived as merely another resident preference, based in culture.

Yeah . . . it’s maybe a cultural thing. We have a lot of black . . . employees, and sometimes residents don’t want someone that’s black taking care of them. It’s a cultural thing I think. (CCA Ontario, white woman)

It was evident in many of our case studies that sexism and racism were often mis-recognized and covered over by a discourse of “difference” and “resident preference”. There was little understanding, for example, that women, who may have experienced gender-based violence, assault and abuse from men in their lives, may express their own experiences of gender subordination in long-term care and feel unsafe with men’s caring. This is one kind of “resident preference”. Quite different in its social underpinnings is a non-racialized resident’s preference for a non-racialized care worker due to racist assumptions or anti-immigrant beliefs that are lodged in the resident’s experiences of belonging to a dominant social group.

In some of the residences we studied, residents had the right to refuse care due to race or gender, and teams worked around these “preferences” about “difference” or “culture”. In this way, racism coming from residents and families was supported by most of these institutions under the name of “preference”, but this strategy also protected racialized workers from having to hear and confront racist behaviours. To be clear, this strategy did little to address racism as an everyday occurrence. It only changed how workers experienced it. It also meant that no real action to confront and eliminate this hazard was taken.

Interviewee: It’s race. Yeah.

Interviewer: And it’s a family or the resident?

Interviewee:No, no. Just the client. For me is nothing but is a serious problem . . . This is a bad thing. You go, you explain these things but there’s no...

Interviewer:Nobody solves the problem.

Interviewee: You have problem here I [would] call police for you.. . [ When there is a] serious problem [the managers] never call police, never. This is a problem. (CCA Ontario black immigrant man)

In some residences, we heard and saw instances when residents refused a worker’s support due to gender or race or a combination, but the worker had decided to convince a resident to accept their care, sometimes out of concern for their job security, sometimes to gain a sense of self-respect. These workers added to their work overload by taking on these challenges.

I don’t care where you’re from, you know. You have to use your state of mind, you know. …when they give you the assignment sheet, you know, [indicating] you cannot work with this man, you cannot work with this lady. If you cannot work with four or five people, you know that[‘s] wrong. You should. That’s it. That’s it. You should make yourself available to learn who is this guy, who she is, okay? When you get there, you know, you should study that person [so you can work with them]. (CCA Ontario black immigrant man)

In the residences we studied, we did not find institutional policies or approaches that provided a more collective or systemic approach to addressing discrimination and disrespect, and, as we have illustrated, many workers took on individual responsibility for dealing with racism and sexism as a result.

Individualizing Responsibility and Costs

While in this analysis individual responsibility for workplace psychological health and safety is presented as problematic, it has received support from some occupational health research literature. Research that measures individual mental health status, personality characteristics and attitudes toward caring as correlates to emotional exhaustion and burnout appear to assume that if gender, personality, personal history and attitude shape susceptibility to hazardous working conditions, then it is the workers who need to change, not the working conditions (a recent example is Gomez-Cantorna et al. 2015). This literature tends to ignore hazards such as disrespect, racism and sexism that affect workers differently. Our research shows that at least some workers have internalized the view that they, and not the workplace, are the problem, accepting some of this individualization of responsibility for psychological health and safety.

[T]here’s a feeling of not enough time to do things properly and sometimes frustration getting out and knowing people are unhappy. But that’s my problem. I mean I don’t have to live with that but I guess I let it fall on my shoulders. I let it upset me. That’s my problem. But yeah, I don’t want to be negative but its an environment that its more negative sometime than positive” (CCA, Ontario)

In our research we assume that people interact with workplace environments and conditions that present psychological hazards. People have different abilities to cope with workplace hazards, but it is better for all workers and those they care for if these hazards are eliminated, minimized or at least recognized and addressed. The costs of not addressing these concerns fall squarely on workers’ lives. Those we interviewed told us about some of the impacts on their personal lives, including problems with sleeping, emotional volatility and struggles to have energy or connection with their own families. They also mentioned taking sick time due to stress and fatigue. Workers were clear that their work conditions wore them out in ways that negatively affected their health and their personal lives.

For me the problem is driving home because your energy level is dropped and all of a sudden you have to negotiate these bad streets with a brain that’s quite addled. (LPN Nova Scotia)

[S]o if you didn’t do a perfect job you got some complaint and maybe the family is ‘Oh something, something’, right? Then you can’t just forget everything. You know, you take this home for sure. You take this home. Then obviously then because home is my place. At least when I’m yelling, when I’m screaming I’m okay, right? You can’t do everything here, right? (CCA, Ontario)

Especially that time it’s so busy it’s like you can’t even sleep wondering if you forgot something. It’s just too much. (CCA, Manitoba)

Of course, it is important to remember that other costs of these psychological health and safety issues fall upon residents, whose needs and requests may not be met and who may interact daily with care workers who are operating at the edges of their psychological and physical limits. Long-term residential care workplace administrators tended to focus on short-term problem-solving to meet immediate needs, like replacing tired, sick and absent workers. Stretched to the limit, these workplaces seemed to have inadequate capacity to address these hazards.

Indicating Promising Practices for Workplace Psychological Health and Safety

In reviewing the care worker interviews in this study, there were indications that some long-term care residences had conditions of work that supported psychological health and safety in some ways. While these are indications, rather than concrete proof, they suggest that within the daunting limitations posed by funding and regulation regimes, individual workplaces can address some of these hazards in important albeit limited ways. Indeed, the purpose of this study is to find ideas worth sharing rather than to make claims about best practices, in part because we think what is effective varies with context.

Practices that appeared promising and worthy of further assessment were: a) more worker autonomy in deciding how and when to do their work; b) team work; c) communication; d) meaningful worker involvement in decision-making; and e) staffing from a permanent roster of people working part-time for that home. These practices were found in workplaces in more than one jurisdiction, suggesting that they are not highly dependent on regulatory regime. On the other hand, these strategies are only possible when there is a relatively stable workforce that works together regularly. Without a basis in trusting relationships, these strategies are unlikely to produce results. Further, they will not erase psychological health and safety hazards, but rather reduce and minimize their effects.

Involving staff in decision-making was revealed in one residence. A number of workers told us about a change in management personnel that improved working conditions and reduced psychological stress. The new manager involved workers by consulting with them and acting on their suggestions about work arrangements.

Interviewee: Yeah, I feel like it’s been a lot better in the last couple of months.

Interviewer: Because you have more autonomy, more right to decide?

Interviewee: I think because we’re involved. (Nova Scotia LPN)

In another residence, workers told us about a higher degree of team work and communication, which relied upon workers’ autonomy to determine how tasks were completed and who worked with the various residents.

“Yes, I mean that’s more or less the individual being able to manage his or her time and I’m able to do that pretty good . . . I’m able to like create my own sort of routine. (RPN, Ontario)

But workers were also clear that workplace strategies were not enough. We have indications that funding and regulatory regimes matter, and most especially, staff-resident ratios that provide more hours of direct nursing care to residents. In order to provide the adequate quality of care that workers want to provide and believe that residents deserve, more direct care hours are necessary. Improved staff-resident ratios were key to both their psychological health and safety and to their maintaining their commitment to the long-term care field.

[The] ratios are key because every nurse and LPN and care aide wants to give amazing care and that’s why we have so many leaving the profession, right? It’s because the ethical and moral distress that you cannot do your job the way you’re supposed to be doing your job and you’re just trying to just make it through the day. So if there was funding put into having, you know, the appropriate ratios then yeah, of course it would work. It would be amazing wouldn’t it? (RN British Columbia)

This analysis calls attention to psychological health and safety hazards in long-term residential care work. Our findings are consistent with other research that has demonstrated that working conditions that include combinations of high demands and low decision latitude and/ or combinations of high efforts and low rewards are hazardous to psychological health. (Stansfeld and Candy 2006), but we suggest here that doing caring work, where the wellbeing of vulnerable others is on the line, intensifies these effects. Further workplace disrespect and discrimination are important to consider in assessing workplace health and safety.

Our analysis also points to the problem of the individualization of responsibility. While other researchers have made important contributions to our knowledge of job strain, moral distress and other worker concerns in long-term residential care, the issues are sometimes framed in ways that reinforce the tendency toward individualized solutions. In their analysis of moral distress in dementia care work, Pijl-Zieber et al. (2016) explain that “the most productive solutions can be arrived at by framing moral distress as a structural concern” (p.17). Others confirm a structural approach, such as research on “structural violence” at work (Banerjee et al. 2012). We agree that how issues are framed is critical to how issues come to be understood and addressed.

We suggest that one useful way forward is to use the frame of psychological health and safety in order to address on-the-job violence, disrespect, sexism and racism, work overload and job strain. Making it clear that these conditions are hazards, through workplace health and safety policies based on Canada’s voluntary standards and negotiated collective agreements, could offer long-term care workers better conditions of work, and afford residents better quality of care. Better yet, Canada could legislate their current voluntary standards, following the example of other countries.

Limitations and Future Research

The results of this analysis add information to the study of long-term residential care work, nursing work and occupational health and safety. The findings support and supplement other research that identifies structural factors that contribute to psychological health and safety hazards in care work. As with any study, this analysis has limitations. The data were not collected with psychological health and safety as a focus, and therefore opportunities to explore the topic with the research respondents were not systematic or extensive. Further, there were insufficient data to compare differently qualified nursing staff and their exposures or experiences. Due to the small numbers of workplaces involved, no conclusions about jurisdiction could be reached. Future research will help to address these questions as well as to compare whether or how legislated psychological health and safety standards in other countries operate to protect workers in long-term residential care, when compared to the Canadian context.

Notes

These nurses are called Registered Practical Nurses (RPN) in Ontario only, but will be referred to as LPNs in this article for all jurisdictions, for consistency and clarity.

These nursing assistants are also called Personal Support Workers (PSW), Personal Care Aides (PCA), Health Care Aides (HCA) and other titles and other names, depending on jurisdiction and facility. All are referred to as CCAs in this article, for consistency and clarity. For more information about these positions, see Laxer et al. (2016). “Comparing Nursing Home Assistive Personnel in Five Countries.” Ageing International 41(1): 62–78.

“Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (Canada) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments, and were approved by university ethics committees at York University and by long-term care home ethics review committees where required.

Gender, race and immigrant status information was not collected uniformly throughout the broad study, and were identified in only some of the interviews. These interviewee social locations were identified in the interviews used in this section of the article, and are mentioned here as necessary context for these aspects of the discussion.

References

Andersen, E. A. (2009). Working in long-term residential care: A qualitative metasummary encompassing roles, working environments, work satisfaction, and factors affecting recruitment and retention of nurse aides. Global Journal of Health Science, 1(2), 2–41.

Armstrong, H., Armstrong, P., Banerjee, A., Daly, T., & Szebehely, M. (2009). They deserve better: The long-term care experience in Canada and Scandinavia. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Armstrong, P. (2004). There are not enough hands: Conditions in Ontario's long-term care facilities. Ottawa: Canadian Union of Public Employees.

Armstrong, P. (2012). The mental health of women health care workers. Thinking women and health care reform in Canada. In P. Armstrong, B. Clow, K. R. Grant et al. Toronto, Women's Press, pp 193-214.

Armstrong, P. (2013a). Regulating care: Lessons from Canadae. In G. Meager and M. Szebehely (eds) Marketisation in Nordic eldercare. Stockholm, Normacare.

Armstrong, P. (2013b). Skills for Care. In P. Armstrong & S. Braedley (Eds.), Troubling care: Critical perspectives on research and practices (pp. 101–112). Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Armstrong, P., Armstrong, H., Banerjee, A., Daly, T., & Szebehely, M. (2011). Structural violence in long-term residential care. Women’s Health and Urban Life, 10(1), 111–129.

Armstrong, P., & Jansen, I. (2015). The mental health of health care workers: A Woman’s issue? In N. Khanlou & B. Pilkington (Eds.), Women's mental health: Resistance and resilience in community and society (pp. 19–32). New York: Springer.

Artazcoz, L., C. Borrell, I. Cortàs, V. Escribà-Agüir and L. Cascant (2007). Occupational epidemiology and work related inequalities in health: a gender perspective for two complementary approaches to work and health research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61(Suppl 2): ii39-ii45.

Astrakianakis, G., Chow, Y., Hodgson, M., Haddock, M., & Ratner, P. (2014). 0421 noise-induced stress among primary Care Workers in Long Term Care Facilities in British Columbia, Canada. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 71(Suppl 1), A54.

Baines, D., & Cunningham, I. (2011). Using comparative perspective rapid ethnography in international case studies: Strengths and challenges. Qualitative Social Work, 1–16.

Bakan, A. A. B., & Stasiulis, D. K. (1997). Not one of the family: Foreign domestic workers in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Banerjee, A., Armstrong, P., Daly, T., Armstrong, H., & Braedley, S. (2015). “Careworkers don't have a voice:” epistemological violence in residential care for older people. Journal of Aging Studies, 33, 28–36.

Banerjee, A., Daly, T., Armstrong, P., Szebehely, M., Armstrong, H., & Lafrance, S. (2012). Structural violence in long-term, residential care for older people: Comparing Canada and Scandinavia. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 390–398.

Barlem, E. L. D., & Ramos, F. R. S. (2015). Constructing a theoretical model of moral distress. Nursing Ethics, 22(5), 608–615.

Bonde, J. P. E. (2008). Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: A systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 65(7), 438–445.

Bourbonnais, R., Comeau, M., Vezina, M., & Dion, G. (1998). Job strain, psychological distress, and burnout in nurses. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 34(1), 20–28.

Braedley, S. (2009). How do work environments affect Women's maternal health? Lessons from Canada. Women & Environments International 80/81(spring 2009): 9-11.

Braedley, S. (2013). A gender politics of long-term care: Towards an analysis. In P. Armstrong & S. Braedley (Eds.), Troubling care: Critical perspectives on research and practices (pp. 59–70). Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Braedley, S., & Martel, G. (2015). Dreaming of home: Long term residential care and (in)equities by design. Studies in Political Economy, 95, 59–81.

Chu, C. H., Wodchis, W. P., & McGilton, K. S. (2014). Turnover of regulated nurses in long-term care facilities. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(5), 553–562.

Daboussy, M., & Uppal, S. (2012). Work absences in 2011. Perspectives on labour and income. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Daly, T. (2015). Dancing the two-step in Ontario’s long-term care sector: More deterrence-oriented regulation = ownership and management consolidation. Studies in Political Economy, 95, 29–58.

Daly, T., Banerjee, A., Armstrong, P., Armstrong, H., & Szebehely, M. (2011). Lifting the ‘violence veil’: Examining working conditions in long-term care facilities using iterative mixed methods. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 30(02), 271–284.

Daly, T., & Szebehely, M. (2011). Unheard voices, unmapped terrain: Care work in long term residential care for older people in Canada and Sweden. International Journal of Social Welfare, 21(2), 139–148.

Egan, M., Bambra, C., Thomas, S., Petticrew, M., Whitehead, M., & Thomson, H. (2007). The psychosocial and health effects of workplace reorganisation. 1. A systematic review of organisational-level interventions that aim to increase employee control. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 61(11), 945–954.

Enns, V., Currie, S., & Wang, J. (2015). Professional autonomy and work setting as contributing factors to depression and absenteeism in Canadian nurses. Nursing Outlook, 63(3), 269–277.

Fujisawa, R., Colombo, F. (2009). The long-term care workforce: Overview and strategies to adapt supply to a growing demand. OECD Health Working Papers, no. 44, OECD. doi:10.1787/225350638472.

Glenn, E. N. (1992). From servitude to service work: Historical continuities in the racial division of paid reproductive labor. Signs, 18(1), 1–43.

Glenn, E. N. (2010). Forced to care: Coercion and caregiving in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gomez-Cantorna, C., Clemente, M., Fariña-Lopez, E., Estevez-Guerra, G. J., & Gandoy-Crego, M. (2015). The effect of personality type on palliative care nursing staff stress levels. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 17(4), 342–347.

Government of Canada. (2013). National Standard of Canada for psychological health and safety in the workplace. Ottawa: Mental Health Commission.

Health Employers Association of British Columbia. (2014). Health and safety in action summary status report phase 1. HEABC: Vancouver.

International Labour Organization (2013). Ten keys for gender-sensitive OSH practice: Guidelines for gender-mainstreaming in occupational safety and health. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Kaiser, H. A. (2009). Canadian mental health law: The slow process of redirecting the ship of state. Health Law Journal, 17, 139–194.

Karasek, R. A., & Theorell, T. (1992). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books.

LaMontagne, A. D., Keegel, T., Louie, A. M., & Ostry, A. (2010). Job stress as a preventable upstream determinant of common mental disorders: A review for practitioners and policy-makers. Advances in Mental Health, 9(1), 17–35.

LaMontagne, A. D., Martin, A., Page, K. M., Reavley, N. J., Noblet, A. J., Milner, A. J., Keegel, T., & Smith, P. M. (2014). Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 131–142.

Laxer, K. (2013). Counting carers in long-term residential care in Canada. In P. Armstrong & S. Braedley (Eds.), Troubling Care (pp. 73–88). Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Laxer, K., Jacobsen, F. F., Lloyd, L., Goldmann, M., Day, S., Choiniere, J. A., & Rosenau, P. V. (2016). Comparing nursing home assistive personnel in five countries. Ageing International, 41(1), 62–78.

Marcella, J., & Kelley, M. L. (2015). “death is part of the job” in long-term care homes. SAGE Open, 5(1), 1–15.

March, L., Smith, E. U., Hoy, D. G., Cross, M. J., Sanchez-Riera, L., Blyth, F., Buchbinder, R., Vos, T., & Woolf, A. D. (2014). Burden of disability due to musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 28(3), 353–366.

Martin, A., Sanderson, K., & Cocker, F. (2009). Meta-analysis of the effects of health promotion intervention in the workplace on depression and anxiety. Scandanavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 35(1), 7–18.

Matheson, A., O'Brien, L., & Reid, J. A. (2014). The impact of shiftwork on health: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(23–24), 3309–3320.

McGilton, K. S., Boscart, V. M., Brown, M., & Bowers, B. (2014). Making tradeoffs between the reasons to leave and reasons to stay employed in long-term care homes: Perspectives of licensed nursing staff. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(6), 917–926.

Messing, K. (1997). Women's occupational health: A critical review and discussion of current issues. Women & Health, 25(4), 39–68.

Messing, K. (1998). One-eyed science: Occupational health and women workers. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Messing, K. (2005). Women's occupational health in Canada: A critical review and discussion of current issues. In Canada, Women's health forum. Canada: Health.

Messing, K., & Mager Stellman, J. (2006). Sex, gender and women's occupational health: The importance of considering mechanism. Environmental Research, 101(2), 149–162.

Messing, K., & Silverstein, B. A. (2009). Gender and occupational health. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 35(2), 81–83.

Muntaner, C., Li, Y., Xue, X., Thompson, T., O’Campo, P., Chung, H., & Eaton, W. W. (2006). County level socioeconomic position, work organization and depression disorder: A repeated measures cross-classified multilevel analysis of low-income nursing home workers. Health & Place, 12(4), 688–700.

Oliffe, J. L., & Han, C. S. (2014). Beyond workers’ compensation Men’s mental health in and out of work. American Journal of Men's Health, 8(1), 45–53.

Oliffe, J. L., & Phillips, M. J. (2008). Men, depression and masculinities: A review and recommendations. Journal of Men's Health, 5(3), 194–202.

Ontario Health and Safety Association. (2010). Ontario health care health and safety committee under section 21 of the occupational health and safety act, guidance note for workplace parties #3, occupational health and safety (OHS) education and training. Toronto: Ontario Health and Safety Associaton.

Page, K. M., LaMontagne, A. D., Louie, A. M., Ostry, A. S., Shaw, A., & Shoveller, J. A. (2013). Stakeholder perceptions of job stress in an industrialized country: Implications for policy and practice. Journal of Public Health Policy, 34(3), 447–461.

Pereira, S. M., Fonseca, A. M., & Carvalho, A. S. (2011). Burnout in palliative care: A systematic review. Nursing Ethics, 18(3), 317–326.

Piers, R. D., Van den Eynde, M., Steeman, E., Vlerick, P., Benoit, D. D., & Van Den Noortgate, N. J. (2012). End-of-life care of the geriatric patient and nurses’ moral distress. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13(1), 80. e87–80. e13.

Pijl-Zieber, E. M., O. Awosoga, S. Spenceley, B. Hagen, B. Hall and J. Lapins (2016). Caring in the wake of the rising tide: Moral distress in residential nursing care of people living with dementia. Dementia 0 (0):1–22.

Public Services Health and Safety Association. (2016). Mental Health Resources. Retrieved 15 July 2016, from http://www.pshsa.ca/mentalhealth/.

Quality Palliative Care in Long Term Care Alliance. (2012). Personal Support Worker Competencies. Retrieved 10 July 2016, from www.palliativealliance.ca/.../QPC_LTC_PSW_Competency_Brochure_Final_May_2_2012_V2_1.pdf.

Rai, G. S. (2010). Burnout among long-term care staff. Administration in Social Work, 34(3), 225–240.

Ray, S. L., Wong, C., White, D., & Heaslip, K. (2013). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, work life conditions, and burnout among frontline mental health care professionals. Traumatology, 19(4), 255–267.

Rosenfield, S. (2012). Triple jeopardy? Mental health at the intersection of gender, race, and class. Social Science & Medicine, 74(11), 1791–1801.

Sabo, B. (2011). Reflecting on the concept of compassion fatigue. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 16(1). http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-16-2011/No1-Jan-2011/Concept-of-Compassion-Fatigue.aspx.

Sabo, B. M. (2006). Compassion fatigue and nursing work: Can we accurately capture the consequences of caring work? International Journal of Nursing Practice, 12(3), 136–142.

Slocum-Gori, S., Hemsworth, D., Chan, W. W., Carson, A., & Kazanjian, A. (2013). Understanding compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout: A survey of the hospice palliative care workforce. Palliative Medicine, 27(2), 172–178.

Squires, J. E., Hoben, M., Linklater, S., Carleton, H. L., Graham, N., & Estabrooks, C. A. (2015). Job satisfaction among care aides in residential long-term care: A systematic review of contributing factors, both individual and organizational. Nursing Research and Practice, 2015, 1–24.

Stansfeld, S., & Candy, B. (2006). Psychosocial work environment and mental health—A meta-analytic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 32(6) 443–462.

Statistics Canada (2012). Work absence rates 2011. Ottawa: Statistics Canada

Szeto, A. C., & Dobson, K. S. (2013). Mental disorders and their association with perceived work stress: An investigation of the 2010 Canadian community health survey. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 191–197.

Tan, L., Wang, M.-J., Modini, M., Joyce, S., Mykletun, A., Christensen, H., & Harvey, S. B. (2014). Preventing the development of depression at work: A systematic review and meta-analysis of universal interventions in the workplace. BMC Medicine, 12, 74–85.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246.

Torjman, S. (2013). Financing long-term care: More money in the mix. Canada: Caledon Institute of Social Policy Ottawa.

Vogel, M., Braungardt, T., Meyer, W., & Schneider, W. (2012). The effects of shift work on physical and mental health. Journal of Neural Transmission, 119(10), 1121–1132.

Yassi, A., & Hancock, T. (2005). Patient safety–worker safety: Building a culture of safety to improve healthcare worker and patient well-being. Healthcare Quarterly, 8, 32–38.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Re-imagining Long-Term Residential Care: An International Study of Promising Practices) and the Canadian Institute for Health Research and the European Institute on Ageing (Healthy Ageing in Residential Places). We are indebted to the Principal Investigator on these projects, Pat Armstrong, and to the co-investigators, for their encouragement and ever helpful critique. Special thanks to Albert Banerjee for his engagement with this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

As there is no person or personal data appearing in the paper, there is no one from whom a permission should be obtained in order to publish personal data.

Ethical Treatment of Experimental Subjects (Animal and Human)

The studies described in this article received ethics review and approval from university and institution-specific Research Ethics Boards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braedley, S., Owusu, P., Przednowek, A. et al. We’re told, ‘Suck it up’: Long-Term Care Workers’ Psychological Health and Safety. Ageing Int 43, 91–109 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-017-9288-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-017-9288-4