Abstract

Background

Mental health disorders in the workplace have increasingly been recognised as a problem in most countries given their high economic burden. However, few reviews have examined the relationship between mental health and worker productivity.

Objective

To review the relationship between mental health and lost productivity and undertake a critical review of the published literature.

Methods

A critical review was undertaken to identify relevant studies published in MEDLINE and EconLit from 1 January 2008 to 31 May 2020, and to examine the type of data and methods employed, study findings and limitations, and existing gaps in the literature. Studies were critically appraised, namely whether they recognised and/or addressed endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity, and a narrative synthesis of the existing evidence was undertaken.

Results

Thirty-eight (38) relevant studies were found. There was clear evidence that poor mental health (mostly measured as depression and/or anxiety) was associated with lost productivity (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism). However, only the most common mental disorders were typically examined. Studies employed questionnaires/surveys and administrative data and regression analysis. Few studies used longitudinal data, controlled for unobserved heterogeneity or addressed endogeneity; therefore, few studies were considered high quality.

Conclusion

Despite consistent findings, more high-quality, longitudinal and causal inference studies are needed to provide clear policy recommendations. Moreover, future research should seek to understand how working conditions and work arrangements as well as workplace policies impact presenteeism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Despite clear evidence that poor mental health is associated with lost productivity at work, more evidence is required to understand the extent to which mental illness decreases productivity and the mechanisms through which this occurs in order to provide appropriate policy responses. |

A better understanding of the relationship between mental illness and worker productivity is needed to understand the trade-offs between presenteeism and absenteeism. |

Workplace policies that limit and help workers manage job stress can help improve workers’ productivity. |

1 Introduction

Mental health disorders in the workplace, such as depression and anxiety, have increasingly been recognised as a problem in most countries. Using a human capital approach, the global economic burden of mental illness was estimated to be US$$2.5 trillion in 2010 increasing to US$$6.1 trillion in 2030; most of this burden was due to lost productivity, defined as absenteeism and presenteeism [1]. Workplaces that promote good mental health and support individuals with mental illnesses are more likely to reduce absenteeism (i.e., decreased number of days away from work) and presenteeism (i.e., diminished productivity while at work), and thus increase worker productivity [2]. Burton et al. provided a review of the association between mental health and worker productivity [3]. The authors found that depressive disorders were the most common mental health disorder among most workforces and that most studies examined found a positive association between the presence of mental health disorders and absenteeism (particularly short-term disability absences). They also found that workplace policies that provide employees with access to evidence-based care result in reduced absenteeism, disability and lost productivity [3].

However, this review is now outdated. Prevalence rates for common mental disorders have increased [4], while workplaces have also responded with attempts to reduce stigma and the potential economic impact [5], necessitating the need for an updated assessment of the evidence. Furthermore, given that most of the global economic burden of mental illness is due to lost productivity [1], it is important to have a good understanding of the existing literature on this outcome. While the previous review focused on the prevalence of certain mental health conditions and the available interventions and workplace policies, this review focused on the measures of lost productivity and the instruments used, as well as the data and methods employed, which the previous review did not examine in depth. Thus, the objectives of this paper were to update the Burton et al. review [3] on the association between mental health and lost productivity, and undertake a critical review of the literature that has been published since then, specifically how researchers have studied this relationship, the type of data and databases they have employed, the methods they have used, their findings, and the existing gaps in the literature.

2 Methods

We undertook a critical review, i.e., a review that presents, analyses and synthesises evidence from diverse sources by extensively searching the literature and critically evaluating its quality [6], ultimately identifying the most significant papers in the field.Footnote 1 We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [7] to guide our analysis. Our review focused on all studies published since 2008, which examined the relationship between mental health and workplace-related productivity among working-age adults. We used the Population, Intervention, Control, Outcomes, and Study design (known as PICOS) criteria to guide the development of the search strategy.

2.1 Eligibility Criteria

The populations of interest comprised working-age adults (18–65 years old). Studies focusing solely on volunteers and/or caregivers (i.e., unpaid workers) were excluded. The intervention(s), or rather more appropriately the exposure(s), had to be a diagnosis of any mental disorder/illness or self-reported mental health problem(s). Any studies that examined substance use and/or physical health in addition to mental health were included if results were reported separately for mental health-related outcomes. The control or comparator group, where applicable, included working age individuals without a mental disorder/illness or mental health problem(s). The outcome(s) included lost workplace productivity measured by absenteeism, presenteeism, sick leave, short- and/or long-term disability, or job loss. Studies that examined productivity of home-related activities (e.g., housework) were excluded. Studies with an observational study design and/or regression analysis were included; randomised control trials, cost-of-illness studies and economic evaluations were excluded (the first two were only included if they examined the relationship between mental health and lost productivity). Only original studies were considered; however, relevant reviews were retained for reference checking to find relevant studies, which may not have been captured by the search strategy.

2.2 Search Strategy

We searched literature published in English from 1 January 2008 to 31 May 2020. Structured searches were done in MEDLINE and EconLit to capture the most relevant literature published in the medical and economics fields, respectively. We also undertook relevant searches in Google and on specific websites of interest (e.g., UK Parliament Hansard, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Centre for Mental Health, the Health Foundation, the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the King’s Fund) and a hand search of the references of key papers [8]. Search terms or strings were developed on the basis of four concepts: population or workplace, intervention/exposure (i.e., presence of mental disorder/illness), work-related outcomes, and study design (see Table 1).

2.3 Study Selection

After duplicate records were removed, one reviewer (LB) screened all titles and abstracts while additional reviewers (CdO and RJ) were brought in for discussion, if/where necessary. Articles were excluded either because they did not examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity (e.g., some cost-of-illness studies) or were mainly focused on physical health. Subsequently, all relevant full-text articles were retrieved and screened by one reviewer (LB) to confirm eligibility; additional reviewers (MS, RJ or CdO) were brought in, if/where necessary.

2.4 Data Extraction

Two reviewers (LB and MS) undertook the data extraction, and an additional reviewer (RJ or CdO) was assigned to resolve any disagreements. The research team developed a data extraction form, based on the Cochrane good practice data extraction form, which included study information (author(s), year of publication), country (where the study was published or conducted), aims of study, study design (cross-sectional, longitudinal), data source(s) (i.e., database(s), surveys/questionnaires), study population (sample size, age range), mental disorder(s) examined, workplace outcome examined (absenteeism, presenteeism, short-term disability, long-term disability, job loss, other), methods employed (statistical analysis, regression model employed), and results/key findings.

2.5 Quality Assessment

We reviewed the methods employed in the studies to assess their quality and robustness, drawing loosely on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, a risk-of-bias assessment tool for observational studies [9]. We paid particular attention to whether studies were able to move beyond simple associations and attempted to address causal inference, where necessary, and whether they took account of endogeneity (i.e., cases where the explained variable and the explanatory variable are determined simultaneously) and/or unobserved heterogeneity (i.e., cases where the presence of unexplained (observed) differences between individuals are associated with the (observed) variables of interest), which are common issues when examining the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. All studies that recognised and/or accounted for these issues were considered high quality. We also examined the type of data/databases employed (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal data and representative, population-based samples), findings, and limitations (and the extent to which these impacted the findings), which were also considered when determining the quality of a study.

2.6 Data Synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of studies examined, undertaking a meta-analysis was not possible. Therefore, we undertook a narrative synthesis of the relevant literature, where we synthesised the existing evidence by mental disorder/illness and workplace outcome (absenteeism, presenteeism, sick leave, short- and long-term disability, or job loss), if/where appropriate.

3 Results

3.1 Study Selection

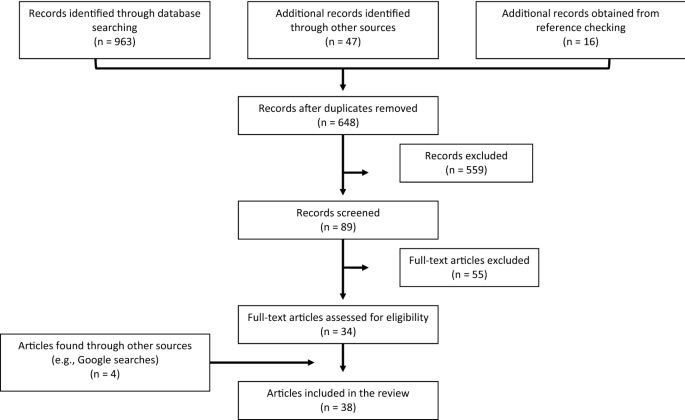

After all citations were merged and duplicates removed, our search produced 648 unique records, of which 89 full texts were assessed; four studies were obtained from other sources (e.g., Google searches). Ultimately, 38 studies were included in the final review [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] (see Fig. 1) and relevant data were extracted (see Table 2 and Table A1 in the Appendix for more details).

3.2 Overview of Studies

All studies focused on individuals typically between the ages of 18 and 64/65 years. Some studies (n = 5) examined individuals 20 or 25 years and older [11, 12, 16, 28, 38] to account for younger individuals who might still be in school and thus not working, while other studies had different lower and upper age limits (e.g., age 15 [25, 47] and age 60 [11, 38] years, respectively). Most studies were from the USA (n = 10; 26%) and the Netherlands (n = 6; 16%); this result is line with the findings from a review of economic evaluations of workplace mental health interventions [48]. The remaining studies were from Australia (n = 4), Japan (n = 4), South Korea (n = 3), multiple countries (n = 4), Brazil (n = 1), Colombia (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), Finland (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), and the United Kingdom (n = 1). Many studies did not specify the setting or industry or state the size of the firm where the study was undertaken (also found elsewhere [48]); consequently, this information was not included in the data extraction form.

3.3 Measures and Instruments/Tools Used

3.3.1 Mental Health

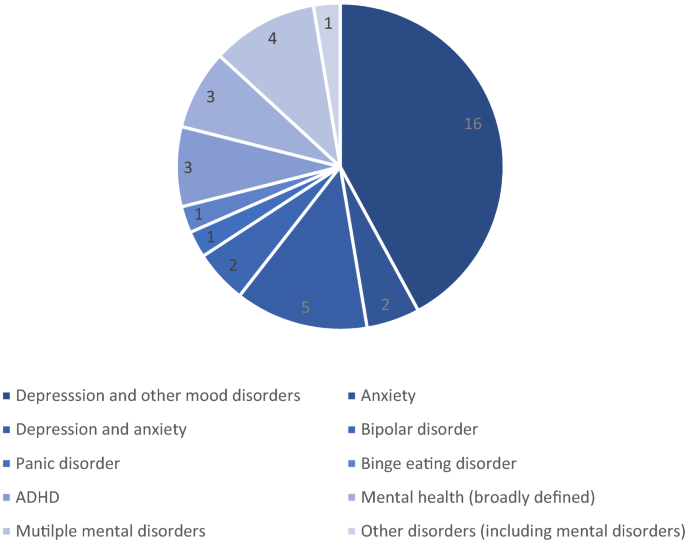

Most studies (n = 16) examined depression/depressive symptoms, major depressive disorder or other mood disorders (see Fig. 2). Two studies examined anxiety and five studied both anxiety and depression. A smaller number of studies examined other disorders—three studies examined attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), two studies focused on bipolar disorder, one examined panic disorder, one studied binge-eating disorder, and one looked at other disorders including mental disorders (depressive symptoms and cognitive function). Three studies looked at mental health broadly speaking (two studies examined poor mental health and another studied common mental disorders). Finally, four studies examined multiple mental disorders (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, emotional disorders, substance use disorders, ADHD). Some studies used a binary indicator for the presence/absence of a mental disorder/poor mental health, while other analyses used different aggregate measures of mental illness or psychological distress, based on the number of recorded symptoms.

A variety of instruments/tools were used to measure mental health, depending on the disorder. Depression was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6 scale) [49], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression scale [50], Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [51], Short General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) [52], Major Depression Inventory (MDI) [53], Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) [54], and Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) [55]. In studies that examined both anxiety and depression (n = 2), the authors used either the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [56] or the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) [57]. In one study [42], severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms was assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory [58] and the Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology questionnaire [59], respectively. In another study [33], mood disorder was measured using the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) [60]. In one study [41], ADHD was assessed using the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey [61]; in another [35], it was assessed using the WHO Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale [62]. Panic disorders were measured using the Panic Disorder Severity Scale [63] in one study [16].

3.3.2 Lost Productivity

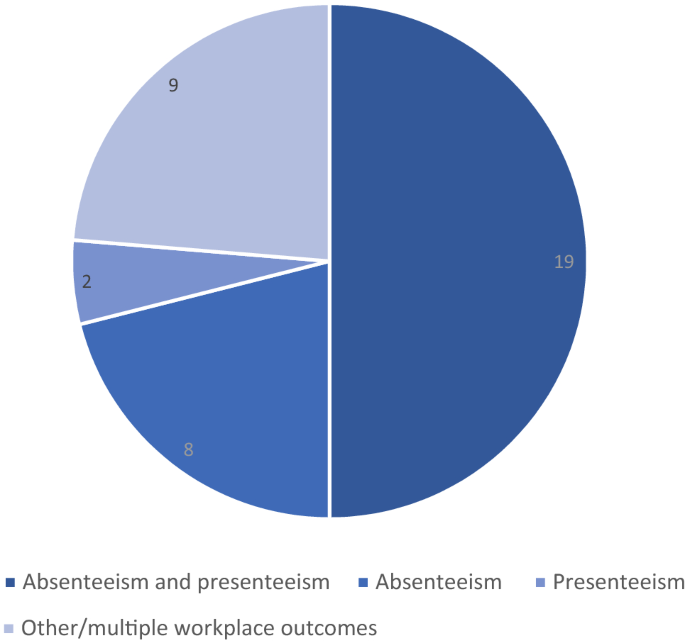

Nineteen studies examined both absenteeism and presenteeism, eight studies examined absenteeism only, two studies examined presenteeism only, and nine examined other or several workplace outcomes, such as employment, absenteeism, presenteeism, workplace accidents/injuries, short- and/or long-term disability, activity impairment and/or job loss (see Fig. 3).

Five studies used the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire [64] (Beck et al. [27], Jain et al. [36], Able et al. [30], Asami et al. [31], Ling et al. [44]); three used the WHO’s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HWP) [65] (Hjarsbech et al. [18], Woo et al. [38], Park et al. [16]) to determine absenteeism and presenteeism. A recent systematic review also found that that the WPAI was most frequently applied in economic evaluations and validation studies to measure lost productivity [66]. Two studies [12, 20] used the Work Limitations Questionnaire [67]. Other studies used a variety of different instruments to measure lost productivity, such as the Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs Associated with Psychiatric illness (TiC-P) [68] (Bokma et al. [26]), the Short-Form Health and Labour Questionnaire [69] (Bouwmans et al. [45]), the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS) [70] (de Graaf et al. [23]) and the Endicott Work Productivity Scale [71] (McMorris et al. [33]). One study [43] made use of four work performance measures to examine lost productivity: WPAI [64], Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) [66], Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS) [71] and Functional Status Questionnaire Work Performance Scale (WPS) [72].

3.4 Data Sources and Methods

3.4.1 Data

Most studies (n = 20) employed data collected through surveys/questionnaires, though some used publicly available datasets, such as the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey [29], the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [28] and the National Latino and Asian American Study [28], the US National Health and Wellness Survey [44], the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey [25, 47], and the Singapore Mental Health Study [24]. One study used administrative claims data [32]. Three studies made use of linked data, such as Hjarsbech et al. [18], which linked questionnaires to the Danish National Register of Social Transfer Payments; Erickson et al. [43], which utilised questionnaires linked to medical records, and Mauramo et al. [34], which used survey data from the Helsinki Health Study linked to employer's register data on sickness absence. Only one study employed trial data [45]. Most studies (n = 29; 76%) employed cross-sectional data; few used longitudinal data (n = 9; 24%).

3.4.2 Methods

Several studies (n = 8) used regression analysis to examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity, namely linear regression [11, 17] and logistic regression models [25, 29, 42, 45]. Two studies employed two-part models, where the first part examined the probability/odds of workers experiencing absenteeism, while the second part modeled the number of hours of absenteeism [10] or the number of work days missed [29]. One paper employed Poisson regressions to model the rate of work-lost days (absenteeism) and work-cut days (presenteeism) [34]. Another study computed Kaplan–Meier survival curves to estimate the mean and median duration of sickness absence due to depressive symptoms [40], and one estimated a Cox's proportional hazards model to analyse whether and to what extent depressive symptoms at baseline predicted time to onset of first long-term sickness absence during the 1-year follow-up period [18]. Only one study employed instrumental variables to address the potential endogeneity of the mental illness variable employed [28] and four employed longitudinal data models [13, 20, 25, 47].

3.5 Evidence Synthesis

Almost all studies (n = 36) found a positive (and, many times, a strong) association between the presence of mental illness/disorders or poor mental health and productivity loss measured by absenteeism and/or presenteeism. Nevertheless, there were a few exceptions—one study found that mood disorders were associated with decreased presenteeism (i.e., work performance) but found no significant relationship between mood disorders and absenteeism [11]. Another study found that individuals with binge-eating disorders reported greater levels of presenteeism and lost productivity than those without but found no effect for absenteeism [44].

Many studies (n = 6) on depression examined both absenteeism and presenteeism where the presence of the former was positively associated with the latter (as was the case for studies, which examined only absenteeism and only presenteeism), and the latter was higher among those with higher severity of depression. These findings held in studies examining major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder (though one study found that symptoms of mania or hypomania were not significantly associated with absenteeism) [14]. Studies examining depression and anxiety (and anxiety alone, including panic disorder) generally examined both absenteeism and presenteeism and found that these disorders were significantly associated with lost productivity. One study found that workers with binge-eating disorder reported greater levels of presenteeism than those without but no differences in absenteeism. All studies on ADHD (n = 3) examined both absenteeism and presenteeism and found ADHD was associated with more days of missed work and poor work performance. Studies looking at mental health (broadly defined) typically examined absenteeism only, finding a positive relationship between both, though the magnitude of the effect was found to be modest in one study [47]. Studies examining multiple disorders (n = 4) also examined both absenteeism and presenteeism. Overall, having a mental disorder was positively associated with lost productivity; however, one study found no significant relationship between mood disorders and alcohol use/dependence and absenteeism [11].

Many studies (n = 6) found that higher severity of the disorder or co-occurring mental health conditions was associated with greater productivity loss. For example, Knudsen et al. found that while comorbid anxiety and depression and anxiety alone were significant risk factors for absenteeism, depression alone was not [37].

Some studies examined outcomes separately for men and women (n = 5) or examined specific groups (n = 1). For example, Ammerman et al. examined high-risk, low-income mothers with major depression and found that depression significantly increased the likelihood of absenteeism (i.e., missing workdays) among this group [29]. However, beyond gender, studies did not report on differences by ethnicity/race and/or age.

Overall, we found that the literature on this topic continues to examine the most common mental disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety) using similar data sources and analysis techniques as the Burton et al. review [3] (see Table 3). However, more recent literature shows that the positive relationship between the presence of mental disorders and lost productivity may not hold in all instances.

4 Discussion

The goal of this review was to provide a comprehensive overview and critical assessment of the most recent literature examining the relationship between mental health and workplace productivity, with a particular focus on data and methods employed. It provides clear evidence that poor mental health is associated with lost productivity, defined as increased absenteeism (i.e., more missed days from work) and increased presenteeism (i.e., decreased productivity at work). However, overall, only three studies were of high quality [25, 28, 47]. Studies with greater rigour and more robust methods, which accounted for unobserved heterogeneity for example, found a similar positive relationship but a smaller effect size [25, 47].

Other reviews have also found large significant associations between measures of mental health and lost productivity, such as absenteeism [3, 73,74,75]. For example, Burton et al. [3] found that depressive disorders were the most common mental health disorder among most workers, with many studies showing a positive association between the presence of mental health conditions and absenteeism, particularly short-term disability absences [3]. However, we found that studies employing superior methodological study design have shown the strength of the observed association may be smaller than previously thought.

Overall, our findings are in line with those from other reviews [73,74,75] and the Burton et al. study [3]. We too found that the most common disorder examined was depression, followed by depression and anxiety, the most studied workplace outcomes were both absenteeism and presenteeism, and that there was an association between mental disorders and both absenteeism and presenteeism. We found that studies employed a variety of data sources, from data collected from surveys/questionnaires to existing surveys and administrative data. Regression analysis was commonly used to examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity, though there were some studies where the most appropriate regression model was not used given the outcome examined (e.g., linear regression models were used regardless of the type of outcome examined).

Some studies employed small sample sizes [20, 43], which are not representative of the broader population and can thus impact the generalizability of findings, and other studies that did use nationally representative population samples employed cross-sectional designs [11, 42, 46], which can limit causal inference. Therefore, the vast majority did not examine the causal effect of mental health on lost productivity, but rather only the association between the two. A notable exception was Banerjee et al. [28], who examined the potential endogeneity of the mental illness variable used. Moreover, few studies employed longitudinal data, which can help account for unobserved heterogeneity (that may be correlated with both mental health and lost productivity) and minimise the potential for reverse causality and omitted variable bias; Wooden et al. [47] and Bubonya et al. [25] were notable exceptions. Wooden et al. found that the association between poor mental health and the number of annual paid sickness absence days was much smaller once they accounted for unobserved heterogeneity and focused on within-person differences [47]. For example, the incidence rate ratios for the number of sickness absence days for employed women and men experiencing severe depressive symptoms were 1.31 and 1.38, respectively, in the negative binomial regression models but dropped to 1.10 and 1.13, respectively, once the authors controlled for unobserved heterogeneity through the inclusion of correlated random effects. Thus, it may be that previous research has overstated the magnitude of the association between poor mental health and lost productivity. More studies with rigorous causal inference are required to help strengthen the ability to make informed policy recommendations.

Few studies explored the factors that might explain absenteeism and/or presenteeism due to mental health. Again, the study by Bubonya et al. was a notable exception [25], providing several important insights on the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. According to the authors, initiatives that limit and help workers manage job stress seem to be the most promising avenue for improving workers’ productivity. Furthermore, the authors found that presenteeism rates among workers with poor mental health were relatively insensitive to work environments, in line with other research from the UK [76]; consequently, they suggested that developing institutional arrangements that specifically target the productivity of those experiencing mental ill health may prove challenging. These findings are particularly important in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic due to changes in work arrangements and workplaces (e.g., working from home while trying to balance work with home and care responsibilities, hybrid working arrangements, and ensuring workplaces have COVID-19-secure measures in place). This work will be of particular interest to employers and decision makers looking to improve worker productivity.

Most literature examined either depression or anxiety or both, the most common mental disorders. Few studies examined mental disorders such as ADHD, bipolar disorder and eating disorders, and no studies examined schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, personality disorder or suicidal/self-harm behaviour. More work is needed on these mental disorders, which, although less prevalent and thus less studied, are potentially more work disabling (despite already low employment rates for individuals with these conditions) [77, 78]. Other research suggests there are important gender differences [25, 28]. For example, Bubonya et al. found that increased job control can help reduce absenteeism for women with good mental health, though not for women in poor mental health [25]. Banerjee et al. found that the impact of poor mental health on the likelihood of being employed and in the labour force is higher for men [28]. Future research should ensure that gender differences, as well as other differences (e.g., age, industry, job conditions), are examined to ensure tailored polices are developed and implemented.

There is also a need to better understand the extent to which mental illness decreases productivity at work and the mechanisms through which this occurs, as this could help inform the role of employment policy and practices to minimise presenteeism [25]. Some research suggests that conducive working conditions, such as part-time employment and having autonomy over work tasks, can help mitigate the negative impact of mental health on presenteeism [76]. Alongside this, it is important to learn more about the dynamics of the relationship between mental illness and worker productivity to understand the trade-offs between presenteeism and absenteeism [25]. For example, it would be helpful to understand whether policies that incentivise workers with mental ill health to take time off improve overall productivity by reducing presenteeism. None of the studies in this review explored this trade-off. Finally, more rigorous research on this topic would help achieve a better understanding of the overall economic impact of mental disorders.

This review is not without limitations. It only included studies obtained from a few select databases and did not include grey literature, and only one reviewer screened the titles and abstracts (though the purpose was not to undertake a systematic review); however, it examined papers and reports from select websites of interest. Furthermore, this review only focused on the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. Although lost productivity is an important labour market outcome, there are other outcomes that mental health can impact such as labour force participation, wages/earnings, and part-time versus full time employment. Finally, this review only included studies published in English and therefore may have missed other relevant studies. Nonetheless, this review has several strengths. It provides an updated review on this topic, thus addressing a critical gap in the literature, and examined the type of data and databases employed, the methods used, and the existing gaps in the literature, thus providing a more comprehensive overview of the research done to date.

5 Conclusion

This review found clear evidence that poor mental health, typically measured as depression and/or anxiety, was associated with lost productivity, i.e., increased absenteeism and presenteeism. Most studies used survey and administrative data and regression analysis. Few studies employed longitudinal data, and most studies that used cross-sectional data did not account for endogeneity. Despite consistent findings across studies, more high-quality studies are needed on this topic, namely those that account for endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity. Furthermore, more work is needed to understand the extent to which mental illness decreases productivity at work and the mechanisms through which this occurs, as well as a better understanding of the dynamics of the relationship between mental illness and worker productivity to understand the trade-offs between presenteeism and absenteeism. For example, future research should seek to understand how working conditions and work arrangements as well as workplace policies (e.g., vacation time and leaves of absence) impact presenteeism.

Notes

This type of review differs from a systematic review, which seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesise existing evidence, often following existing guidelines on the conduct of a review.

References

Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, et al. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011.

Hamberg-van Reenen HH, Proper KI, van den Berg M. Worksite mental health interventions: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69:837–45.

Burton WN, Schultz AB, Chen C, Edington DW. The association of worker productivity and mental health: a review of the literature. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2008;1(2):78–94.

McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T, editors. Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2016.

Mental wellbeing at work. Public health guideline [PH22]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph22 (Accessed 28 July 2021).

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097.

Christensen MK, Lim CCW, Saha S, Plana-Ripoll O, Cannon D, Presley F, Weye N, Momen NC, Whiteford HA, Iburg KM, McGrath JJ. The cost of mental disorders: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29: e161.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses; 2013. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

Uribe JM, Pinto DM, Vecino-Ortiz AI, Gómez-Restrepo C, Rondón M. Presenteeism, absenteeism, and lost work productivity among depressive patients from five cities of Colombia. Value Health Reg Issues. 2017;14:15–9.

Tsuchiya M, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, Fukao A, Tachimori H, Iwata N, Uda H, Nakane H, Watanabe M, Oorui M, Naganuma Y, Furukawa TA, Kobayashi M, Ahiko T, Takeshima T, Kikkawa T. Impact of mental disorders on work performance in a community sample of workers in Japan: the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002–2005. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198(1):140–5.

Toyoshima K, Inoue T, Shimura A, Masuya J, Ichiki M, Fujimura Y, Kusumi I. Associations between the depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and presenteeism of Japanese adult workers: a cross-sectional survey study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2020;14:10.

Suzuki T, Miyaki K, Song Y, Tsutsumi A, Kawakami N, Shimazu A, Takahashi M, Inoue A, Kurioka S. Relationship between sickness presenteeism (WHO-HPQ) with depression and sickness absence due to mental disease in a cohort of Japanese workers. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:14–20.

Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Unützer J, Operskalski BH, Bauer MS. Severity of mood symptoms and work productivity in people treated for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(6):718–25.

Lamichhane DK, Heo YS, Kim HC. Depressive symptoms and risk of absence among workers in a manufacturing company: a 12-month follow-up study. Ind Health. 2018;56(3):187–97.

Park YL, Kim W, Chae JH, Seo OhK, Frick KD, Woo JM. Impairment of work productivity in panic disorder patients. J Affect Disord. 2014;157:60–5.

Johnston DA, Harvey SB, Glozier N, Calvo RA, Christensen H, Deady M. The relationship between depression symptoms, absenteeism and presenteeism. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:536–40.

Hjarsbech PU, Andersen RV, Christensen KB, Aust B, Borg V, Rugulies R. Clinical and non-clinical depressive symptoms and risk of long-term sickness absence among female employees in the Danish eldercare sector. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):87–93.

Hilton MF, Scuffham PA, Vecchio N, Whiteford HA. Using the interaction of mental health symptoms and treatment status to estimate lost employee productivity. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(2):151–61.

Hees HL, Koeter MW, Schene AH. Longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms and work outcomes in clinically treated patients with long-term sickness absence related to major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(2–3):272–7.

Fernandes MA, Ribeiro HKP, Santos JDM, Monteiro CFS, Costa RDS, Soares RFS. Prevalence of anxiety disorders as a cause of workers’ absence. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(suppl 5):2213–20.

Evans-Lacko S, Knapp M. Global patterns of workplace productivity for people with depression: absenteeism and presenteeism costs across eight diverse countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1525–37.

de Graaf R, Tuithof M, van Dorsselaer S, ten Have M. Comparing the effects on work performance of mental and physical disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(11):1873–83.

Chong SA, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Subramaniam M. Mental disorders: employment and work productivity in Singapore. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(1):117–23.

Bubonya M, Cobb-Clark DA, Wooden M. Mental health and productivity at work: does what you do matter? Labour Econ. 2017;46:150–65.

Bokma WA, Batelaan NM, van Balkom AJ, Penninx BW. Impact of anxiety and/or depressive disorders and chronic somatic diseases on disability and work impairment. J Psychosom Res. 2017;94:10–6.

Beck A, Crain AL, Solberg LI, Unützer J, Glasgow RE, Maciosek MV, Whitebird R. Severity of depression and magnitude of productivity loss. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(4):305–11.

Banerjee S, Chatterji P, Lahiri K. Effects of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes: a latent variable approach using multiple clinical indicators. Health Econ. 2017;26(2):184–205.

Ammerman RT, Chen J, Mallow PJ, Rizzo JA, Folger AT, Van Ginkel JB. Annual direct health care expenditures and employee absenteeism costs in high-risk, low-income mothers with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:386–94.

Able SL, Haynes V, Hong J. Diagnosis, treatment, and burden of illness among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Europe. Pragmat Obs Res. 2014;5:21–33.

Asami Y, Goren A, Okumura Y. Work productivity loss with depression, diagnosed and undiagnosed, among workers in an Internet-based survey conducted in Japan. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(1):105–10.

Curkendall S, Ruiz KM, Joish V, Mark TL. Productivity losses among treated depressed patients relative to healthy controls. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(2):125–30.

McMorris BJ, Downs KE, Panish JM, Dirani R. Workplace productivity, employment issues, and resource utilization in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Med Econ. 2010;13(1):23–32.

Mauramo E, Lallukka T, Lahelma E, Pietiläinen O, Rahkone O. Common mental disorders and sickness absence. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(6):569–75.

Kessler RC, Lane M, Stang PE, Van Brunt DL. The prevalence and workplace costs of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a large manufacturing firm. Psychol Med. 2009;39(1):137–47.

Jain G, Roy A, Harikrishnan V, Yu S, Dabbous O, Lawrence C. Patient-reported depression severity measured by the PHQ-9 and impact on work productivity: results from a survey of full-time employees in the United States. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(3):252–8.

Knudsen AK, Harvey SB, Mykletun A, Øverland S. Common mental disorders and long-term sickness absence in a general working population. The Hordaland Health Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(4):287–97.

Woo JM, Kim W, Hwang TY, Frick KD, Choi BH, Seo YJ, Kang EH, Kim SJ, Ham BJ, Lee JS, Park YL. Impact of depression on work productivity and its improvement after outpatient treatment with antidepressants. Value Health. 2011;14(4):475–82.

Harvey SB, Glozier N, Henderson M, Allaway S, Litchfield P, Holland-Elliott K, Hotopf M. Depression and work performance: an ecological study using web-based screening. Occup Med (Lond). 2011;61(3):209–11.

Koopmans PC, Roelen CA, Groothoff JW. Sickness absence due to depressive symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81(6):711–9.

de Graaf R, Kessler RC, Fayyad J, ten Have M, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Borges G, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, de Girolamo G, Haro JM, Jin R, Karam EG, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J. The prevalence and effects of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the performance of workers: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(12):835–42.

Plaisier I, Beekman AT, de Graaf R, Smit JH, van Dyck R, Penninx BW. Work functioning in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders: the role of specific psychopathological characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):198–206.

Erickson SR, Guthrie S, Vanetten-Lee M, Himle J, Hoffman J, Santos SF, Janeck AS, Zivin K, Abelson JL. Severity of anxiety and work-related outcomes of patients with anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(12):1165–71.

Ling YL, Rascati KL, Pawaskar M. Direct and indirect costs among patients with binge-eating disorder in the United States. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(5):523–32.

Bouwmans CA, Vemer P, van Straten A, Tan SS, Hakkaart-van RL. Health-related quality of life and productivity losses in patients with depression and anxiety disorders. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(4):420–4.

Buist-Bouwman MA, Ormel J, de Graaf R, de Jonge P, van Sonderen E, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R, Vollebergh WA, ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators. Mediators of the association between depression and role functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(6):451–8.

Wooden M, Bubonya M, Cobb-Clark D. Sickness absence and mental health: evidence from a nationally representative longitudinal survey. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42(3):201–8.

de Oliveira C, Cho E, Kavelaars R, Jamieson M, Bao B, Rehm J. Economic analyses of mental health and substance use interventions in the workplace: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):893–910.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–76.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Goldberg D, Hillier V. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9(1):139–45.

Bech P, Rasmussen N-A, Olsen LR, Noerholm V, Abildgaard W. The sensitivity and specificity of the Major Depression Inventory, using the Present State Examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord. 2001;66:159–64.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE Jr, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care. 1991;29(2):169–76.

Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29.

Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(12):1069–77.

Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–7.

Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996;26(3):477–86.

Hirschfeld RM. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a simple, patient-rated screening instrument for bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(1):9–11.

Kessler RC, Haro JM, Heeringa SG, et al. The World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Epidemiol Psychiatr Soc. 2006;15:161–6.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Jin R, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Walters EE. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–56.

Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, et al. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1571–5.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–65.

Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, Berglund P, Cleary PD, McKenas D, Pronk N, Simon G, Stang P, Üstün TU, Wang P. The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(2):156–74.

Hubens K, Krol M, Coast J, Drummond MF, Brouwer WBF, Uyl-de Groot CA, Hakkaart-van RL. Measurement instruments of productivity loss of paid and unpaid work: a systematic review and assessment of suitability for health economic evaluations from a societal perspective. Value Health. 2021;24(11):1686–99.

Lerner D, Amick BC 3rd, Rogers WH, Malspeis S, Bungay K, Cynn D. The Work Limitations Questionnaire. Med Care. 2001;39(1):72–85.

Hakkaart-Van Roijen L. Manual. Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness (TiC-P adults); 2010. http://www.bmg.eur.nl/english/imta/publications/questionnaires_manuals.

van Roijen L, Essink-Bot M, Koopmanschap MA, et al. Labor and health status in economic evaluation of health care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1996;12(3):405–15.

Janca A, Kastrup M, Katschnig H, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Mezzich JE, Sartorius N. The World Health Organization Short Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS-S): a tool for the assessment of difficulties in selected areas of functioning of patients with mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31(6):349–54.

Endicott J, Nee J. Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS): a new measure to assess treatment effects. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):13–6.

Jette AM, Davies AR, Cleary PD, Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Fink A, Kosecoff J, Young RT, Brook RH, Delbanco TL. The Functional Status Questionnaire: reliability and validity when used in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1(3):143–9.

Duijts SFA, Kant I, Swaen GMH, van den Brandt PA, Zeegers MPA. A meta-analysis of observational studies identifies predictors of sickness absence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(11):1105–15.

Darr W, Johns G. Work strain, health, and absenteeism: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol. 2008;13(4):293–318.

Lerner D, Henke RM. What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity? J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(4):401–10.

Bryan ML, Bryce AM, Roberts J. Presenteeism in the UK: effects of physical and mental health on worker productivity; 2020; SERPS no. 2020005. ISSN 1749-8368. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/media/12544/download.

Cook JA. Employment barriers for persons with psychiatric disabilities: update of a report for the President’s Commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1391–405.

Luciano A, Meara E. Employment status of people with mental illness: national survey data from 2009 and 2010. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(10):1201–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kath Wright for her help with the search strategy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication (from patients/participants)

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

CdO and RJ conceived and developed the protocol study. LB undertook the search and screened all titles and abstracts. MS extracted the data. CdO and RJ adjudicated any discrepancies in the full-text review. CdO wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CdO and RJ supervised the project. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the manuscript. All authors take sole responsibility for the content.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira, C., Saka, M., Bone, L. et al. The Role of Mental Health on Workplace Productivity: A Critical Review of the Literature. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 21, 167–193 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00761-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00761-w