Abstract

Claims of widespread sexism in academic science frequently appear both in the mainstream media and in prestigious science journals. Often these claims are based on an unsystematic sampling of evidence or on anecdotes, and in many cases these claims are not supported by comprehensive analyses. Here we illustrate the importance of considering the full corpus of scientific data by focusing on a recent set of claims by two philosophers of science who argue that researchers who fail to find evidence of sexism in some domains of academia–such as tenure-track hiring, grant funding, journal reviewing, letters of recommendation, and salary–are as epistemically and socially problematic as are those who deny claims of anthropogenic climate change. We argue that such claims are misguided, and the result of ignoring important evidence. We show here that when the totality of evidence is considered, claims of widespread sexism are inconsistent with the canons of science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Others have made a similar claim. For example, Bakker and Jacobs (2016) argued that “Convergent evidence is so evocative that denying gender bias in academia would be equivalent to denying climate change.”.

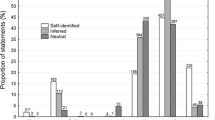

Multiple studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals show that ~ 97% of actively publishing climate scientists agree that global warming over the last century is extremely likely to be the result of human activities, a conclusion endorsed by the leading scientific organizations worldwide: “The number of papers rejecting AGW [Anthropogenic, or human-caused, Global Warming] is a miniscule proportion of the published research, with… an overwhelming percentage (97.2% based on self-ratings, 97.1% based on abstract ratings) endorses the scientific consensus on AGW.” (Cook et al., 2016, p. 6) Contrast this consensus with claims that gender bias is systemic and pervasive in the tenure-track academy. The latter boasts no comparable degree of consensus nor is it based on comprehensive data treatment, rendering the comparison misguided.

Witteman et al., to their credit, also list areas in which women are not disadvantaged.

L&P assert that we used flawed methodology by dint of examining gender bias in tenure-track hiring among highly qualified applicants: “by selecting only top-qualified candidates to examine gender bias in hiring processes in academia (Williams and Ceci 2015b), they clearly make poor.

methodological choices.” This criticism ignores the reality that finalists for most tenure-track positions are unambiguously excellent, something we heard repeatedly from participants in our 2015 series of experiments. However, because this was anecdotal, in Spring, 2020 we decided to test this claim more systematically. We conducted a national stratified survey of tenure-track faculty in eight fields, seven of which are STEM fields, asking faculty to rate on a 10-point scale the competence of their short-listed applicants in their most recent tenure-track search. 279 tenure-track faculty responded and their median rating was 9.0 out of 10.0 (Q3-Q1 = 2.55, indicating clustering at the right tail); 88.5% of these respondents said the top candidate in their search was between very strong and truly outstanding. Even their top three applicants were all rated, on average, as excellent. This seems to be a reality in tenure-track hiring–applicants who make it to the short list based on their CVs, letters, interviews, talks, etc. are regarded by those doing the hiring as excellent. Such unambiguous excellence is not always the case when hiring postdocs, lab managers, and student employees.

A stage 1 registered replication has been attempting to replicate the Moss-Racusin et al. findings and it will be interesting to see their results. If the team—composed of both supporters and critics of the Moss-Racusin et al. findings–fails to replicate, it will undermine the claim of gender bias even at lower levels than professorial hiring, since this study is the most cited evidence of hiring bias (Ceci et al., 2023).

For example, a national analysis of computer science hiring was commissioned by the Computer Research Association (Stankovic & Aspray, 2003). Women PhD-holders applied for fewer academic jobs than men (6 positions vs. 25 positions), yet they were offered twice as many interviews per application (0.77 vs. 0.37 per application). And women received 0.55 job offers per application vs. 0.19 for men: “Obviously women were much more selective in where they applied, and also much more successful in the application process” (p. 31)(http://archive.cra.org/reports/r&rfaculty.pdf).

Card et al. (2022) showed that between 1960 and 1990 women had a lower chance of being inducted into the highly prestigious National Academies of Science and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; however, this disadvantage became neutralized around 1990, and by 2000, women were 3 to 15 times more likely to be inducted into the these organizations than men with comparable publications and citations.

References

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C., & Rosati, F. (2016). Gender bias in academic recruitment. Scientometrics, 106, 119–141.

Bakker, M. M., & Jacobs, M. H. (2016). Tenure track policy increases representation of women in senior academic positions, but is insufficient to achieve gender balance. PLoS One, 11(9), e0163376. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163376

Bian, L., Leslie, S.-J., & Cimpian, A. (2017). Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests. Science, 355, 389–391. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah6524

Birkelund, G. E., Lancee, B., Larsen, E. N., Polavieja, J. G., Radl, J., & Yemane, R. (2022). Gender discrimination in hiring: Evidence from a cross-national harmonized field experiment. European Sociological Review, 38(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcab043

Bol, T., de Vaan, M., & van de Rijt, A. (2022). Gender-equal funding rates conceal unequal evaluations. Research Policy, 51(1), 104399.

Brennan, S. (2013). Rethinking the moral significance of micro-inequities: The case of women in philosophy.” In Hutchison & Jenkins (Eds.) Women in philosophy: What needs to change? Oxford UK: Oxford University Press. 180–96.

Card, D., DellaVigna, S., Funk, P., & Iriberri, N. (2023). Gender gaps at the academies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(4), e2212421120.

Carey, J. M., Carman, K. R., Klayton, K. P., Horiuchi, Y., Htun, M., & Ortiz, B. (2020). Who wants to hire a more diverse faculty? A conjoint analysis of faculty and student preferences for gender and racial/ethnic diversity. Politics, Groups and Identities, 8, 535–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1491866

Carlsson, M., Finseraas, H., Midtbøen, A. H., & Rafnsdóttir, G. L. (2021). Gender bias in academic recruitment? Evidence from a survey experiment in the Nordic region. European Sociological Review, 37(3), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa050

Carnap, R. (1950). Logical foundations of probability. University of Chicago Press.

Casselman, B. (2021). For women in economics, the hostility is out in the open. The New York Times.

Castell, A. (1935). A college logic: An introduction to the study of argument and proof. Macmillan.

Ceci, S. J. (2018). Women in academic science: Experimental findings from hiring studies. Educational Psychologist, 53(1), 22–41.

Ceci, S. J., Ginther, D. K., Kahn, S., & Williams, W. M. (2014). Women in academic science: A changing landscape. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(3), 75–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614541236

Ceci, S. J., Kahn, S., & Williams, W. M. (2021). Stewart–Williams and Halsey argue persuasively that gender bias is just one of many causes of women’s underrepresentation in science. European Journal of Personality, 35, 40–44.

Ceci, S. J., Kahn, S., & Williams, W. M. (2023). Gender bias persist in two of six key domains in academic science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1, 1–59.

Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2011a). Understanding current causes of women’s under-representation in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(8), 3157–3162.

Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2011b). Understanding current causes of women’s underrepresentation in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 3157–3162. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1014871108

Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2015). Women have substantial advantage in STEM faculty hiring, except when competing against more-accomplished men. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1532.

Ceci, S. J., Williams, W. M., & Barnett, S. M. (2009). Women’s underrepresentation in science: Sociocultural and biological considerations. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 218–261.

Ceci, S.J. & Williams, W.M. (2020). The psychology of fact-checking. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-psychology-of-fact-checking1/.

Chan, H. F., & Torgler, B. (2020). Gender differences in performance of top cited scientists by field and country. Scientometrics, 125, 2421–2447.

Coil, A. (2017). Why men don’t believe the data on gender bias in science. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/why-men-dont-believe-the-data-on-gender-bias-in-science/.

Cook, J., Oreskes, N., Doran, P., Anderegg, W., Verheggen, B., Maibach, E., et al. (2016). Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002

Cvencek, D., Meltzoff, A. N., & Greenwald, A. G. (2011). Math–gender stereotypes in elementary school children. Child development, 82(3), 766–779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01529.xpmid:21410915

Eaton, A. A., Saunders, J. F., Jacobson, R. K., & West, K. (2020). How gender and race stereotypes impact the advancement of scholars in STEM: Professors’ biased evaluations of physics and biology post-doctoral candidates. Sex Roles, 82, 127–141.

El-Hout, M., Garr-Schultz, A., & Cheryan, S. (2021). Beyond biology: The importance of cultural factors in explaining gender disparities in STEM preferences. European Journal of Personality, 35, 45–50.

Hargens, L. L., & Long, J. S. (2002). Demographic inertia and women’s representation among faculty in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 73(4), 494–517.

Henningsen, L., Horvath, L. K., & Jonas, K. (2021). Affirmative action policies in academic job advertisements: Do they facilitate or hinder gender discrimination in hiring processes for professorships? Sex Roles, 86, 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-021-01251-4

Hiscox, M. J., Oliver, T., Ridgway, M., Arcos-Holzinger, L., Warren, A., & Willis, A. (2017). Going blind to see more clearly: Unconscious bias in Australian Public Service (APS) shortlisting processes. Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government. https://www.pmc.gov.au/domestic-policy/behavioural-economics/going-blind-see-more-clearly-unconscious-bias-australian-public-service-aps-shortlisting-processes.

Huang, J., Gates, A. J., Sinatra, R., & Barabási, A.-L. (2020). Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914221117

Koch, A. J., D’Mello, S. D., & Sackett, P. R. (2015). A meta-analysis of gender stereotypes and bias in experimental simulations of employment decision making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 128–161.

Lavy, V., & Sand, E. (2015). On the origins of gender human capital gaps: Short and long term consequences of teachers’ stereotypical biases (NBER Working Paper 20909). http://www.nber.org/papers/w20909.pdf.

Leuschner, A., & Pinto, M. F. (2021). How dissent on gender bias in academia affects science and society: Learning from the case of climate change denial. Philosophy of Science, 88, 573–593.

Lippa, R. (1998). Gender-related individual differences and the structure of vocational interests: The importance of the people–things dimension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 996–1009.

Lubinski, D. (2010). Neglected aspects and truncated appraisals in vocational counseling: Interpreting the interest-efficacy association from a broader perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 226–238.

Lubinski, D., & Humphreys, L. G. (1997). Incorporating general intelligence into epidemiology and the social sciences. Intelligence, 24, 159–201.

Lutter, M., & Schröder, M. (2016). Who becomes a tenured professor, and why? Panel data evidence from German sociology, 1980–2013. Research Policy, 45(5), 999–1013.

Madison, G., & Fahlman, P. (2020). Sex differences in the number of scientific publications and citations when attaining the rank of professor. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1723533

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(41), 16474–16479.

National Research Council. (2010). Gender differences at critical transitions in the careers of science, engineering, and mathematics faculty. National Academies Press.

National Academy of Sciences. (2007). Beyond bias and barriers: Fulfilling the potential of women in academic science and engineering. National Academies.

Reuben, E., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2014). How stereotypes impair women’s careers in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 111, 4403–4408.

Rörstad, K., & Aksnes, D. (2015). Publication rate expressed by age, gender and academic position—A large-scale analysis of Norwegian academic staff. Journal of Informetrics, 9, 317–333.

Schröder, M., Lutter, M., & Habicht, I. M. (2021). Publishing, signaling, social capital, and gender: Determinants of becoming a tenured professor in German political science. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0243514. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243514

Stankovic, J., & Aspray, W. (2003). Recruitment and retention of faculty in computer science and engineering. Washington: Computing research association.

Steinpreis, R. E., Anders, K. A., & Ritzke, D. (1999). The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study. Sex Roles, 41(7–8), 509–528.

Stewart-Williams, S., & Halsey, L. G. (2021a). Men, women, & STEM: Why the differences and what should be done? European Journal of Personality, 35, 3–39.

Stewart-Williams, S., & Halsey, L. G. (2022). Not biology or culture alone: Response to El-Hout et al. (2021). European Journal of Personality, 36(6), 991–996.

Su, R., & Rounds, J. (2015). All STEM fields are not created equal: People and thing interests explain gender disparities across STEM fields. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00189

Su, R., Rounds, J., & Armstrong, P. (2009). Men and things, women and people: A meta-analysis of sex differences in interests. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 859–884.

Wenneras, C., & Wold, A. (1997). Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature, 387, 341–343.

Williams, W. M., & Ceci, S. J. (2015). National hiring experiments reveal 2:1 faculty preference for women on STEM tenure track. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(17), 5360–5365.

Witteman, H. O., Hendricks, M., Straus, S., & Tannenbaum, C. (2019). Are gender gaps due to evaluations of the applicant or the science? A natural experiment at a national funding agency. Lancet, 393, 531–540.

Witze, A. (2020). Three extraordinary women run the gauntlet of science—A documentary. Nature, 583, 25.

Funding

The authors declare that this study has no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the paper’s conception and writing. The first draft of the manuscript was mostly written by SJC and WMW commented and extended the argument in all versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

This article does not contain any studies involving animals performed by any one of the author. This article does not contain any studies involving human participatents performed by any one of the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ceci, S.J., Williams, W.M. Are Claims of Fairness Toward Women in the Academy “Manufactured”? The Risk of Basing Arguments on Incomplete Data. Sexuality & Culture 28, 1–20 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10133-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10133-8