Abstract

Currency crises are the most common type of financial crisis in recent decades, but little is known about how the public views these events. This paper argues that voters’ perceptions of their economic self-interests in general, and their employment prospects in particular, influence their attitudes about currency crises and preferred policy responses. We hypothesize that individuals with high degrees of job insecurity will be more concerned about currency depreciation, more opposed to orthodox policy responses such as raising the interest rate, and more supportive of unorthodox policy responses, such as intensifying capital controls. Data from nationally representative surveys in two countries experiencing currency crises recently—Argentina and Turkey—support our argument. A follow-up survey experiment in Turkey, which randomly primed some respondents about deteriorating labor market conditions, provides further evidence. Overall, the results show that concerns about the labor market have a strong and systematic influence on how voters respond to currency crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Calculations based on data from the World Development Indicators

These studies draw on surveys conducted in the USA (Bearce and Tuxhorn 2017), Serbia, and the UK (Aklin et al. 2022), and China (Gueorguiev et al. 2020). Aklin et al. (2022) also conducted a survey in Argentina, a country with a much less stable exchange rate, but that survey did not ask questions about exchange rate depreciation.

Some prior scholarship examines how individuals’ concerns about unemployment shape their preferences for domestic macroeconomic policies, drawing on a “Phillips curve”-type trade-off between inflation and unemployment (e.g., Scheve 2004; Jayadev 2008). While domestic macroeconomic policies often force a choice between reducing unemployment versus lowering inflation, currency crashes typically worsen both inflation and unemployment in the short term. For this reason, the logic of the Phillips curve is less applicable to the contexts we are studying here. Put differently, individuals’ concerns about job loss and their concerns about inflation (e.g., Aklin et al. 2022) are both likely to shape attitudes about depreciation, but these two considerations are unlikely to be closely linked to one another in this issue area.

On the other hand, the maintenance of a stable and competitive real exchange rate has the potential to reduce unemployment (Frenkel and Ros 2006). This suggests that the short-term impact of nominal exchange rate changes differs from the longer-term impact of real exchange rate levels.

This difference is statistically significant (p < 0.01). Our analysis is based on all countries with available data from the World Bank from 1960 to 2018, where we defined a currency crash as depreciations greater than 25% compared to the previous year.

A third policy option is to sell foreign reserves, but this is often not a sustainable solution since reserves will eventually run out in severe currency crises.

Over the long run, capital controls can reduce the efficient allocation of capital (e.g., Forbes 2007), which could dampen growth rates and therefore eventually create problems for the labor market. Our argument instead focuses on the short-term stabilizing effects of capital controls on the job market because we expect voters to pay more attention to these more immediate impacts. Moreover, empirical studies fail to find any clear or consistent relationship between capital controls and growth over the long run (e.g., Kose et al. 2009; Rodrik and Subramanian 2009).

Marx and Picot (2020, 359) note that experimental studies are a “[p]romising way to tackle” the endogeneity problems that may afflict observational studies of this topic.

However, in early 2022, in an effort to combat ongoing pressure on the lira, Turkey imposed a form of “soft capital controls” (Reuters 2022).

Data come from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database.

Details on the designs of the three surveys fielded are presented in Appendix.

When the lira depreciates, many Turkish households respond by transferring their savings out of lira and into dollars (Malsin and Hirtenstein 2021). By the end of 2018 (the year of the survey), foreign currency accounts constituted about 11% of all savings accounts (The Banks Association of Turkey 2019), and by volume, 49% of bank deposits in the country were held in foreign currency (Fitch 2022).

These differences (insecure workers vis-à-vis other workers, the unemployed, and those not in labor force) are all statistically significant at p < 0.01 except for the insecure worker vs. other worker difference for the outcome variable “Support Capital Controls,” which is statistically significant at p < 0.10.

Unfortunately, this survey did not ask about employment status. The question about job insecurity was asked to everyone. The baseline group in the regression is those that did not answer the question about job insecurity. While we cannot be certain that respondents in the “do not know/did not answer” categories (the left-out group in the regression) are not employed, this appears to be the most likely explanation. Consistent with this interpretation, only 20% of those of working age (20–69 years old) did not answer the question, compared to 34% for respondents aged 16–19, and 57% of respondents aged 70 or above.

During the period of fieldwork of this survey (June–August 2019), unemployment had increased to around 14% from around 12.5% in spring of the same year (Turkish Statistical Institute). The increase in youth unemployment (aged 15–24) was particularly steep from around 23 to 27%. Unemployment levels continued to remain high for the rest of the year.

There were two additional response categories to this question: “no one in the household has a job” and a no-response category. The total percentages of these responses are 11% and 12% in the treatment and control groups, respectively. Our experimental results are robust to the exclusion of these respondents from the analysis.

We do not include controls because the treatment is randomly assigned. A likelihood ratio test from the logistic regression of treatment on respondents’ socio-demographics characteristics, reported in Table 8 of Appendix, is statistically insignificant, suggesting that randomization was successful.

References

Ahlquist, John, Mark Copelovitch, and Stefanie Walter. 2020. The political consequences of external economic shocks: Evidence from Poland. American Journal of Political Science 64 (4): 904–920.

Akcay, Ümit, and Ali Riza Güngen. 2019. The making of Turkey’s 2018-2019 economic crisis. In Working Paper No. 120. Institute of International Political Economy Berlin.

Alt, James E., Amalie Jensen, Horacio Larreguy, David D. Lassen, and John Marshall. 2022. Diffusing political concerns: How unemployment information passed between social ties influences Danish voters. The Journal of Politics 84 (1): 383–404.

Aklin, M., E. Arias, and J. Gray. 2022. Inflation concerns and mass preferences over exchange-rate policy. Economics and Politics 34 (1): 5–40.

Baccaro, Lucio, and Diego Rei. 2007. Institutional determinants of unemployment in OECD countries: Does the deregulatory view hold water? International Organization 61 (3): 527–569.

Ball, Laurence, Daniel Leigh, and Prakash Loungani. 2017. Okun’s law: Fit at 50? Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 49 (7): 1413–1441.

Ball, Laurence, Nicolás De Roux, and Marc Hofstetter. 2013. Unemployment in Latin America and the Caribbean. Open Economies Review 24 (3): 397–424.

Bearce, David H., and Kim-Lee Tuxhorn. 2017. When are monetary policy preferences egocentric? American Journal of Political Science 61 (1): 178–193.

Brooks, Sarah M., and Marcus J. Kurtz. 2007. Capital, trade, and the political economies of reform. American Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 703–720.

Brutger, Ryan, and Brian Rathbun. 2021. Fair share? Equality and equity in American attitudes toward trade. International Organization 75 (3): 880–900.

Carranza, Luis, Jose E. Galdon-Sanchez, and Javier Gomez-Biscarri. 2011. The relationship between investment and large exchange rate depreciations in dollarized economies. Journal of International Money and Finance 30 (7): 1265–1279.

Conover, Pamela Johnston, Stanley Feldman, and Kathleen Knight. 1986. Judging inflation and unemployment: The origins of retrospective evaluations. Journal of Politics 48 (3): 565–588.

Tella, Di, Robert J. Rafael, and MacCulloch, and Andrew J. Oswald. 2001. Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. American Economic Review 91 (1): 335–341.

Drezner, Daniel W. 2008. The realist tradition in American public opinion. Perspectives on Politics 6 (1): 51–70.

Economist. 2019. “Argentina faces the prospect of another default.” . https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/turkeys-steps-calm-lira-crisis-bolster-fx-reserves-2022-01-27/ (accessed 05/31/2022).

Erduman, Yasemin, Okan Eren, and Selçuk Gül. 2020. Import content of Turkish production and exports. Central Bank Review 20 (4): 155–168.

Erten, Bilge, and José Antonio Ocampo. 2017. Macroeconomic effects of capital account regulations. IMF Economic Review 65 (2): 193–240.

Fallon, Peter R., and Robert E.B. Lucas. 2002. The impact of financial crises on labor markets, household incomes, and poverty. World Bank Research Observer 17 (1): 21–45.

Fitch. 2022. “Turkish depositors slow to switch to FX-protected lira deposits.” February 3. https://www.fitchratings.com/research/banks/turkish-depositors-slow-to-switch-to-fx-protected-lira-deposits-03-02-2022 (accessed 05/17/2023).

Forbes, Kristin. 2007. The microeconomic evidence on capital controls: No Free Lunch. In Capital Controls and Capital Flows in Emerging Economies, ed. Sebastian Edwards. University of Chicago Press.

Frenkel, Roberto, and Jaime Ros. 2006. Unemployment and the real exchange rate in Latin America. World Development 34 (4): 631–646.

Frieden, Jeffry A. 1991. Invested interests: The politics of national economic policies in a world of global finance. International Organization 45 (4): 425–451.

Gueorguiev, Dimitar, Daniel McDowell, and David A. Steinberg. 2020. The impact of economic coercion on public opinion. Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (9): 1555–1583.

Gupta, Poonam, Deepak Mishra, and Ratna Sahay. 2007. Behavior of output during currency crises. Journal of International Economics 72 (2): 428–450.

Hacaoglu, Selcan, and Cagan Koc. 2017. “Erdoğan denies capital controls in curbing wealth smuggling.” Bloomberg. December 4. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-12-04/erdogan-urges-government-to-prevent-smuggling-of-wealth-abroad (accessed 05/31/2022)

Hacker, Jacob S., Philipp Rehm, and Mark Schlesinger. 2013. The insecure American: Economic experiences, financial worries, and policy attitudes. Perspectives on Politics 11 (1): 23–49.

Halac, M., and S.L. Schmukler. 2004. Distributional effects of crises. Economia 5 (1): 1–67.

Helleiner, Eric. 1994. States and the reemergence of global finance: From Bretton Woods to the 1990s. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Herrmann, Richard K., Philip E. Tetlock, and Matthew N. Diascro. 2001. How Americans think about trade: Reconciling conflicts among money, power, and principles. International Studies Quarterly 45 (2): 191–218.

Hutchison, Michael M., and Ilan Noy. 2005. How bad are twins? Output costs of currency and banking crises. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 37 (4): 725–752.

Jayadev, Arjun. 2008. The class content of preferences towards anti-inflation and anti-unemployment policies. International Review of Applied Economics 22 (2): 161–172.

Jennings, Will, and Christopher Wlezien. 2011. Distinguishing between most important problems and issues? Public Opinion Quarterly 75 (3): 545–555.

Kaplan, Ethan, and Dani Rodrik. 2002. “Did the Malaysian capital controls work?” In Preventing currency crises in emerging markets, 393–440. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kirshner, Jonathan. 1995. Currency and coercion: The political economy of international monetary power. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Klandermans, Bert, John Klein Hesselink, and Tinka van Vuuren. 2010. Employment status and job insecurity: On the subjective appraisal of an objective status. Economic and Industrial Democracy 31 (4): 557–577.

Kose, Ayhan, Eswar Prasad, Kenneth Rogoff, and Shang-Jin Wei. 2009. Financial globalization: A reappraisal. IMF Staff Papers 56: 8–62.

Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2018. Systemic banking crises revisited. IMF Working Paper.

Malsin, Jared, and Anna Hirtenstein. 2021. “Turks abandon the lira for dollars as currency crisis deepens.” Wall Street Journal November 25. https://www.wsj.com/articles/turks-switch-savings-to-u-s-dollars-as-local-currency-collapses-11637859160 (accessed 05/17/2023).

Mander, Benedict, and Colby Smith. 2019. “Argentina imposes currency controls.” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/2387309c-cce9-11e9-99a4-b5ded7a7fe3f (accessed 05/31/2022).

Mansfield, Edward D., and Diana C. Mutz. 2009. Support for free trade: Self-interest, sociotropic politics, and out-group anxiety. International Organization 63 (3): 425–457.

Marinova, Dani M., and Eva Anduiza. 2020. When bad news is good news: Information acquisition in times of economic crisis. Political Behavior 42 (2): 465–486.

Marx, Paul. 2014. The effect of job insecurity and employability on preferences for redistribution in Western Europe. Journal of European Social Policy 24 (4): 351–366.

Marx, Paul, and Georg Picot. 2020. Three approaches to labor-market vulnerability and political preferences. Political Science Research and Methods 8 (2): 356–361.

Muñoz de Bustillo, Rafael, and Pablo De Pedraza. 2010. Determinants of job insecurity in five European countries. European Journal of Industrial Relations 16 (1): 5–20.

Näswall, Katharina, and Hans De Witte. 2003. Who feels insecure in Europe? Predicting job insecurity from background variables. Economic and Industrial Democracy 24 (2): 189–215.

Nucci, Francesco, and Alberto F. Pozzolo. 2001. Investment and the exchange rate: An analysis with firm-level panel data. European Economic Review 45 (2): 259–283.

Nucci, Francesco, and Alberto Franco Pozzolo. 2010. The exchange rate, employment and hours: What firm-level data say. Journal of International Economics 82 (2): 112–123.

Obstfeld, Maurice, and Alan M. Taylor. 1997. The great depression as a watershed: International capital mobility over the long run. In The defining moment, ed. Michael Bordo, Claudia Goldin, and Eugene White. University of Chicago Press.

Obstfeld, Maurice, Jay C. Shambaugh, and Alan M. Taylor. 2005. The trilemma in history: Tradeoffs among exchange rates, monetary policies, and capital mobility. Review of Economics and Statistics 87 (3): 423–438.

OECD. 2018. OECD economic surveys: Turkey 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Paldam, Martin, and Peter Nannestad. 2000. What do voters know about the economy? A study of Danish data, 1990–1993. Electoral Studies 19 (2–3): 363–391.

Pond, Amy. 2018. Worker influence on capital account policy. International Interactions 44 (2): 244–267.

Rankin, David M. 2001. Identities, interests, and imports. Political Behavior 23 (4): 351–376.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2011. From financial crash to debt crisis. American Economic Review 101 (5): 1676–1706.

Reuters. 2021. “Turkey not consider capital controls – Erdoğan adviser.” March 29. https://www.reuters.com/article/turkey-economy-control-int/turkey-not-considering-capital-controls-erdogan-adviser-idUSKBN2BL1RX (accessed 05/31/2022).

Reuters. 2022. “Factbox: Turkey’s steps to calm lira crisis, bolster FX reserves.” January 27. https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/turkeys-steps-calm-lira-crisis-bolster-fx-reserves-2022-01-27/ (accessed 05/31/2022).

Rho, Sungmin, and Michael Tomz. 2017. Why don’t trade preferences reflect economic self-interest? International Organization 71 (1): 85–108.

Rodrik, Dani, and Arvind Subramanian. 2009. Why did financial globalization disappoint? IMF Staff Papers 56: 112–138.

Scheve, Kenneth. 2004. Public inflation aversion and the political economy of macroeconomic policymaking. International Organization 58 (1): 1–34.

Schiumerini, Luis, and David A. Steinberg. 2020. The black market blues: The political costs of illicit currency markets. Journal of Politics 82 (4): 1217–1230.

Steinberg, David A. 2022. How voters respond to currency crises: Evidence from Turkey. Comparative Political Studies 55 (8): 1332–1365.

Steinberg, David, and Stephen Nelson. 2019. The mass political economy of capital controls. Comparative Political Studies 52 (11): 1575–1609.

Sturzenegger, Federico. 2019. Macri’s macro. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: 339–411.

The Banks Association of Turkey. 2019. Banks in Turkey 2018. Available at https://www.tbb.org.tr/en/Content/Upload/Dokuman/161/Banks_in_Turkey_2018.pdf

Acknowledgements

The research in this article was reviewed and approved by Koç University Committee on Human Research (protocol no. 2017.127.IRB3.069).

Funding

This research was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK, Project No. 217K178).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Turkey and Argentina in Comparative Perspective

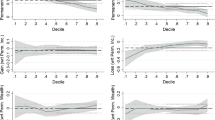

Table 2 lists all countries whose currencies depreciated more than 20% against the US Dollar between 2017 and 2019. Figure 5 shows the trend in annual unemployment rates in Turkey and Argentina. Figure 6 presents the monthly lira/dollar exchange rate from the start of the Erdoğan era (March 2003) until the end of 2019. The dashed vertical lines show the months of the July 2018 and July 2019 Turkey surveys. As can be seen, the first survey coincides with the intensification of the currency crisis. Figure 7 presents the monthly peso/dollar exchange rate during the era of Mauricio Macri’s government. The vertical dashed line is the month of the 2019 Argentina survey. One of the sharpest depreciations of the peso (more than 20%) during this period happened in August 2019, when the incumbent government performed poorly in the first stage of the presidential elections. The market responded negatively to this outcome due to increased political uncertainty and the anticipation of a leftward shift in government. The survey was fielded just 2 months after, in October 2019.

Information About the Surveys

The 2018 Turkey survey was fielded shortly after the 2018 general election, between July 2 and July 7. The survey is a nationally representative sample of 2021 voting-age individuals. The sampling procedure, implemented by the reputable firm Frekans Research (http://www.frekans.com.tr), first randomly selected clusters within each of the country’s ten main geographic regions and then randomly sampled individuals within those clusters. The interviews were conducted face-to-face. Descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analyses are presented in Table 3.

The 2019 Turkey survey was fielded between June 24 and August 2, 2019. The survey is a nationally representative sample of 2021 voting-age individuals. The sampling procedure for the survey starts with the use of Turkish Statistical Institute’s (TUIK) NUTS-2 regions. The target sample was distributed according to each region’s share of urban and rural population in accordance with current records of the Address Based Population Registration System (ADNKS). Household addressed was randomly selected and provided by TUIK. Selection of individuals in households is done on the basis of reported target population of 18 years or older in each household according to a lottery method. If for any reason that individual could not respond to our questions in our first visit, then the same household is visited up to three times until a successful interview is conducted. All interviews were conducted face-to-face by Frekans Research (http://www.frekans.com.tr) in respondents’ households. Descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analyses are in Table 4.

The Argentina survey was administered by an Argentine polling company (Isonomía Consultores) to 1851 Argentine adults between October 14 and 22, 2019, and was designed to be representative of Argentina’s urban population. Data was collected using a combination of face-to-face interviews and telephone surveys based on random-digit dialing. The sample was stratified by the country’s major economic regions and by city sizes. Quotas were set by gender, age group, and the level of educational attainment for the head of household. Table 5 presents descriptive statistics from this survey.

Supplementary Empirical Results

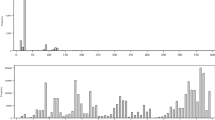

Table 6 presents the full regression results for the 2018 Turkey survey while Table 7 presents complete regression results for the Argentina survey. Using the 2019 Turkish survey experimental data, Table 8 shows that treatment assignment, which is the dependent variable in this model, is not correlated with demographic attributes. Figure 8 displays histograms of the dependent variable, for control group respondents, in the 2019 Turkish survey.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Aytaç, .E., Steinberg, D. Economic Insecurity and Voter Attitudes about Currency Crises. St Comp Int Dev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-023-09399-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-023-09399-8