Abstract

Blacks have been farming in the USA for about four centuries and in Michigan since the 1830s. Yet, for blacks, owning and retaining farmland has been a continuous challenge. This historical analysis uses environmental justice and food sovereignty frameworks to examine the farming experiences of blacks in the USA generally, and more specifically in Michigan. It analyzes land loss, the precipitous decline in the number of black farmers, and the strategies that blacks have used to counteract these phenomena. The paper shows that the ability of blacks to own and operate farms has been negatively impacted by lack of access to credit, segregation, relegation to marginal and hazard-prone land, natural disasters, organized opposition to black land ownership, and systemic discrimination. The paper examines the use of cooperatives and other community-based organizations to help blacks respond to discrimination and environmental inequalities. The paper assesses how the farming experiences of blacks in Michigan compare to the experiences of black farmers elsewhere. It also explores the connections between Michigan’s black farmers, southern black farmer cooperatives, and Detroit’s black consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When one thinks of Michigan, the image that first comes to mind is not one of rural agriculture, yet Michigan is an important agricultural state in the USA. In 2015, Michigan lead the nation in the production of several categories of dry beans, blueberries, pickling cucumbers, tart cherries, and squash and is second leading producer of asparagus, all dry beans, carrots, celery, and Niagara grapes (National Agricultural Statistics Service 2016, p. 1). It is even more unlikely for people to conjure up images of black farmers when they think of Michigan, yet blacks—despite declines in their numbers—have a long and compelling history of farming in the state.

This paper uses the frameworks of environmental justice and food sovereignty to trace the history of black farmers in the USA and the state of Michigan. It analyzes the historical and contemporary constraints that black farmers face and their hardiness as it discusses how Michigan’s black farmers respond to these challenges. It also discusses ways in which black farmers in the state perceive of and try to empower themselves as they enhance food sovereignty and food security in black communities. This paper provides a fresh look at black agricultural experiences through its focus on Michigan. To date, very few research papers have examined the topic of black farmers in Michigan. The comparison between Michigan and the rest of the country has uncovered interesting and enduring North-South relationships that are understudied and deserve more scholarly attention. The paper is also important because if we are going to reverse the trend of land loss and decline in farming among blacks effectively, we need to examine farming among blacks in much broader contexts than have traditionally been undertaken.

Conceptual Framework

This paper employs two conceptual frameworks—environmental justice and food sovereignty—to analyze black participation in farming. Environmental justice identifies and articulates racist and discriminatory acts that result in racial inequities in the environmental realm. Proponents of the environmental justice thesis assert that blacks and other people of color are subject to racist and discriminatory acts, policies, practices, and decision-making that result in racial inequities. Hence, environmental justice seeks redress for perceived unfair acts (Taylor 2000, p. 536; Taylor 2014, pp. 33–46). It is appropriate to analyze black agricultural experiences through the lens of environmental justice as there is extensive documentation of the links between agriculture and the emergence and perpetuation of environmental inequalities in black communities (e.g., see Taylor 2014; Lerner 2005; Bullard 1993).

Food justice and food sovereignty are narrative frames that occupy critical spaces in the discourses about food production and sustainability. Food justice and food sovereignty discourses combine interest in sustainability and consumption of healthy foods with concerns about social justice, equitable access to healthy foods, and control over the production of said food. Minority-led food justice and food sovereignty movements are often rooted in environmental justice principles. Hence, they address inequalities in the food system by blending demands for human rights and sovereignty with the quest for social justice. Food sovereignty advocates believe that control of the means of food production, distribution, and consumption are critical elements to the empowerment and survival of blacks and other disadvantaged groups (White 2010, 2011a; Yakini 2010, 2013; Taylor 2000, 2014; Taylor and Ard 2015).

A National Overview

Historical Context

Free and enslaved blacks have farmed the American soil for almost four centuries. One of the earliest black farm owners in the USA is believed to be Anthony (Antonio) Johnson, an Angolan, who was brought to Jamestown in colonial Virginia in 1619 as an indentured servant. After gaining his freedom around 1835, Johnson and his wife, Mary, grew corn and tobacco on their 250-acre farm. The wealthy couple later moved to Somerset County, Maryland, where they cultivated 300 acres of land (Berlin 1998; Hinson and Robinson 2008, p. 284; Foner 1980; Breen and Innis 1980, pp. 10–17).

The Johnson’s success is unusual because it was difficult for blacks to own land and operate farms of their own. There were legislative attempts to prohibit black landownership as early as 1818, and the barriers erected to prevent blacks from acquiring land in the South were very effective. In only one state, Virginia, was there substantial black landowners. In 1860, blacks owned 13,000 tracts of land in the state’s Tidewater counties (Gray 1949, p. 528; Fisher 1973, p. 481). Up until the early 1860s, black landownership was realized in a haphazard fashion. As the Civil War waned, attempts to sell land to blacks became more structured. The first attempt at organized land distribution involving blacks occurred in 1862 when William Tecumseh Sherman ordered confiscated Confederate plantations to be sold (Reynolds 2002, p. 20; Pease and Pease 1963, pp. 139–141; Hinson and Robison 2008, p. 286).

Farming by free blacks accelerated during reconstruction as increased numbers of blacks acquired their own land. The Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1865 called for 40-acre parcels to be carved out of abandoned plantations and unsettled lands and sold to former slaves. That year, about 40,000 blacks were settled on tracts on the Carolina Sea Islands and cultivated thousands of acres of environmentally vulnerable lands in swamps, tidal flats, river bottomlands, and flood zones. The opposition to black landownership was strong and some blacks were forced off the land they had acquired. Consequently, by late 1865, Andrew Johnson’s administration halted the Union Army’s efforts to distribute land to blacks. A second Freedmen’s Bureau Act was passed in 1866 but it had no specifications for distributing tracts of land to blacksFootnote 1(Bennett 1993, pp. 186–191; Reynolds 2002, p. 2–3; Shannon 1968, p. 84). Eventually, most of the land confiscated from former plantation owners were restored to the former owners and the impact of the Freedmen’s Bureau was quite limited (Fisher 1973, p. 482). The government’s reluctance to subdivide plantations hindered widespread distribution of land to blacks (Reynolds 2002, p. 3).

Some blacks did manage to obtain land through the Southern Homestead Act of 1866. Patterned after the 1862 Homestead Act, the Southern Homestead Act was in effect from 1866 to 1876 and was intended to help freed slaves and whites who took an oath of loyalty to gain access to 80-acre parcels of farmland. The Act opened up and sold off about 46.4 million acres of land in the public domain in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi; however, much of this land was pine woods and swamplands that were unfit for cultivation. Blacks seeking homesteads were threatened, intimidated, or barriers erected to make it difficult for them to participate in the program. This was the case because white plantation owners saw independent black land owners and farmers as a threat to the plantation system that was heavily dependent on cheap and servile labor. Consequently, only 4000 of the 67,600 applicants to the program were black. Notwithstanding, blacks secured homesteads in Florida, Arkansas, and Georgia (Franklin and Moss Jr. 1994, p. 234; Meinig 2000, pp. 195–198; Oliver and Shapiro 1996, pp. 14–15; Oubre 1978; Ferguson 1998, pp. 37–38).

A system of forced labor based on tenancy and peonage laws bound most blacks to the plantations as effectively as slavery. Thus, in 1890, seven out of every eight blacks worked on a plantation or as a domestic servant. However, the Second Morrill Act which enabled the establishment of state agricultural colleges for black students was passed in 1890. The agricultural program at Tuskegee Institute was one of these programs (Reynolds 2002, p. 5). Despite this development, peonage in the form of share cropping and tenant farming remained common. Though peonage laws were found unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 1911, a year later roughly 250,000 blacks were still being held to service on southern plantations against their will (Bennett 1993, pp. 218, 245–249; 252–255; Drake and Cayton 1993, p. 53; Tolnay and Beck 1991, p. 25).

Notwithstanding, black landownership grew during the second half of the nineteenth century. W. E. B. Du Bois estimates that collectively blacks owned 3 million acres of land in 1875, 8 million in 1890, and 12 million in 1900 (Du Bois 1935, p. 4). By 1910, blacks owned roughly 16 million acres of farmland (Schweninger 1989, pp. 41–69; Daniel 2007, p. 3). However, the practice of selling or placing blacks on marginal, degraded, hazard prone, or agriculturally unproductive lands was so commonplace that Du Bois referred to these as waste lands (Du Bois 1901, p. 665; Fisher 1973, p. 483).

Blacks farmed significant acreage, but by the early part of the twentieth century, black landownership and farming began to plummet. Nationwide, blacks constituted 13% of the farmers in 1900 (see Table 1); however, they operated 29.4% of the least valuable farms and only 1% of the most valuable ones. The most common crops grown by black farmers were cotton and rice. That is, 49.1% of the farmers growing cotton were black, so were 37.3% of those growing rice, 18.3% of those growing tobacco, 14.8% of those growing sugar, and 10% of those growing vegetables. Black farm operators were so dependent on cotton that 70.5% derived their primary income from cotton. Another 6.9% obtained their primary income from hay and grain, 4.1% from livestock, and 2.6% from tobacco (U.S. Census Bureau 1902, pp. 48–112).

At the turn of the twentieth century, most of the black farmers did not own the land on which they farmed. Hence in 1900, around 75% of the black farm operators were tenant farmers and sharecroppers. In comparison, about 30% of white farm operators were tenant farmers and share croppers. Most of the black farmers also lived in the South. Blacks farmed about 38.2 million acres and the total value of their farm property was roughly $450 million. The farms blacks operated tended to be small—87.3% of the farms were less than 100 acres in size. At the time, 58% of white-operated farms were less than a hundred acres (U.S. Census Bureau 1902, pp. 48–112).

As Table 1 shows, the number of black farmers in the USA had declined dramatically since peaking in 1920. At their peak, black farm operators comprised 14.3% of the total farmers in the USA. They farmed approximately 41.4 million acres and their operations were worth an estimated $2.3 billion (U.S. Census Bureau 1922, pp. 293–313).

The USDA’s Farm Service AgencyFootnote 2 responded to the nationwide loss of farmland by helping to create farming settlements during the 1930s. Roughly 13 of the more than 100 farming settlements that the agency created were all-black. This was a short-lived project as the Farm Service Agency phased out its resettlement and coop-building programs after 1941 (Zabawa and Warren 1998, pp. 480–483; Wood and Ragar 2012, p. 18; Reynolds 2002, p. 10). Early on, environmental inequalities were evident in the spatial configuration of the resettlement projects. Though some of the resettlement communities had white and black farmers, the two groups were segregated such that one section of the community had only white farmers and the other only black farmers. This was the case with Tillery/Roanoke Farms. The all-white portion of the settlement was called Roanoke Farms, while blacks occupied the Tillery Farms portion. When the settlement was being constructed, the section that became Tillery was originally intended for white homesteaders. The farms were partitioned and construction began on two-story homes. However, whites complained that the Roanoke River tended to flood and they did not want to live in the flood zone. White farmers suggested that blacks be settled in the floodplain instead. They requested that the higher grounds be allocated to whites. Once it was decided that whites would be settled away from the river, no more two-story homes were constructed in the area designated for black occupancy. The Roanoake River flooded in 1940, destroying about half of the Tillery project (Wood and Ragar 2012, pp. 18–20). Hence in the case of Roanoke and Tillery, residential space, location of farms, exposure to hazards, risk, and size and quality of housing were racialized in a way that placed blacks at a disadvantage. That is, the different levels of risk that blacks and whites in the settlement faced impacted the profitability of their farms and their ability to keep the farms solvent.

Other actions of the Farm Service Agency were also detrimental to blacks. For example, decisions related the agency’s operations—such as the granting of loans—are vested in a local committee structure and blacks have had little say in Farm Service Agency’s committees. For instance, there are nearly 3000 county agricultural offices nationwide and less than 2% of county committee members are black. As a result, separate procedures, loan packages, and levels of oversight are applied to black and white farmers routinely (Wood and Ragar 2012, p. 24). In 2015, only 10.5% of the employees of the Farm Service Agency were African Americans (Partnership for Public Service 2016).

Understanding Land Loss Among Black Farmers

The number of black farmers hit an all-time low in 1997 when the census recorded 18,541 of them. That year, black farmers comprised only 1% of the total number of farmers in the country (U. S. Department of Agriculture 1999, pp. 25–26). Heirs’ property is one contributing factor to farmland loss among blacks. Heirs’ property exist when a landowner dies without leaving a will and the property is passed on to multiple inheritors. Property of this nature is frequently divided up. Once the land is partitioned and sold off or distributed to various heirs, the remaining parcels might be too small to maintain viable farms (Southern Coalition for Social Justice 2009; Dyer 2006; Mitchell 2001, pp. 505–511, 2005, pp. 557–615).

There are several other factors that help to account for the decline in black farmland ownership.

Social, economic, and environmental push factors propelled blacks to move from the rural South to the urban South and points West, and from the South to the North. Escalating racial violence (executions, lynchings,Footnote 3 imprisonment, convict leasing, assault, threats, and intimidation); Jim Crow laws; economic and labor market structure (low wages, share cropping and debt peonage, confinement to the secondary labor market, and constrained job opportunities); and environmental disasters (the boll weevil,Footnote 4 as well as devastating rains and floods that ravaged cotton crops in 1915 and 1916 in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida) motivated blacks to move. The flood of 1927 and the drought of 1930–1931 were also contributing factors as these events put sharecroppers and tenant farmers in desperate straits. In addition, the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression decimated farmers’ income. In the North, pull factors such as a less hostile racial climate and expanding economic opportunities prompted blacks to migrate. The Great Migration—the movement of blacks from the South to the North and West—marks one of the greatest redistribution of population in American history. At its peak, blacks left the South at the rate of about 16,000 per month (Bennett 1993, p. 269; Drake and Cayton [1945] 1993, pp. 58, 62; Tolnay and Beck 1991, pp. 20–21, 25; Marks 1991, p. 36; Auerbach 1966, pp. 3–74; Grubbs 1971; U.S. Census Bureau 1922, 1975; Merem 2006, pp. 88–92; Hinson and Robinson 2008, p. 287).

Another major factor contributing to the decline in the number of black farmers was systemic discrimination by federal agencies administering agricultural services. The Jim-Crow-era segregation and environmental injustices evident in access to housing, public transportation, schools, and other facilities was also evident in the delivery of agricultural services. Black and white farmers received separate and unequal services from units like the Cooperative Farm Demonstration Service (Ferguson 1998, pp. 35–36).

New Deal programs ushered in an era of increased government services to farmers that was distributed and controlled through politically connected groups in rural areas. However, these programs exacerbated the inequities that arose from earlier programs. Because blacks had little or no access to the networks that controlled the programs, they were easily marginalized or ignored. Even today, blacks still have limited access to the committees and groups that make important decisions related to farming (Reynolds 2002, p. 9; Merem 2006, pp. 88–92).

Institutional racism was so apparent that in 1965, the US Commission on Civil Rights issued a scathing report that found that widespread discrimination against black farmers by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). The report also found that the discrimination resulted in loss of farmland. In 1997, a civil rights action team outlined strategies the USDA could take to eliminate discrimination (Daniel 2013, p. 1; Merem 2006, pp. 88–92; Whayne 1998, p. 523; U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 1965; Freeman 1965; Daniel 2013, p. 1).

Farmers’ Cooperatives as a Survival Strategy

Early Efforts to Establish Black-White Alliances

Blacks developed cooperatives and used this collective action strategy to help them survive in the agricultural sector. Unjust work conditions on the plantations led to increasing militancy among blacks and attempts to forge alliances with white workers. At the end of the 1880s, a populist rural movement of agrarian radicalism, the Farmers’ Alliance, swept across the South. However, members of the Alliance were hesitant to incorporate blacks into the movement. A black minister and farmer, J. W. Carter, resolved the stalemate when he organized the Colored Farmers’ Alliance in 1889. By 1890, more than a million black farmers were members of the Colored Farmers National Alliance and Cooperative Union.Footnote 5 The organization helped members secure loans to purchase farms (Bennett 1993, pp. 256–257; Tolnay and Beck 1991, p. 24; Reynolds 2002, p. 5; Knapp 1969, pp. 57–67; Goodwyn 1976, pp. 278–285; Hinson and Robinson 2008, p. 288).

A separate form of collective action got underway in 1890. This initiative was modeled after the village improvement associations that started in New England and spread to the rest of the country.Footnote 6 In his desire to help black farmers break the cycle of debt and crop liens, Robert Smith, a principal from East Texas, formed the Farmers’ Improvement Society. The Society established a buying cooperative and focused on helping families operate on a cash basis. The organization had 2340 members by 1900 in Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas and coop members owned 46,000 acres of farmland. They also organized the Farmers’ Improvement Bank to help farmers obtain financing for their operations (Reynolds 2002, pp. 6–7). Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute also helped blacks establish farms in the 1890s. Under Washington’s guidance, the Southern Improvement Company was formed in 1901. The Company purchased a 4000-acre tract of land with funding obtained from a group of northern philanthropists; subdivided it and sold parcels to black farmers. Washington and Tuskegee also created the Tuskegee Farm and Improvement Company (also known as Baldwin Farms) in 1914. The Company, which remained operational till 1949, also purchased and operated an 18,400-acre tract of land in Alabama (Reynolds 2002, pp. 7–8; Zabawa and Warren 1998, pp. 467–469; Anderson 1978, p. 114).

The USDA created the Cooperative Farm Demonstration Service in 1903 to limit the impact of the boll weevil on the lands of white farmers. When the outbreak spread and ravaged black farms, the USDA created a Negro Cooperative Farm Demonstration Service at Tuskegee Institute and hired black agents to serve black farmers. Even with the deployment of black agents to help black farmers learn about crops, some argue that the controversial Negro Cooperative Farm Demonstration Service was of limited success (Ferguson 1998, pp. 35–36; Hersey 2006, pp. 258–259).

The Southern Tenants Farmers Union

Despite limited success in building cross-racial farmer’s alliances, blacks and whites joined forces in 1934 in Arkansas to form the Southern Tenants Farmers Union (STFU). The STFU tried to reform the sharecropping and tenancy system as the boll weevil, floods, and drought made it difficult for sharecroppers and tenant farmers to survive. The STFU helped to form the Unemployment League to put pressure on the Agricultural Adjustment Administration to create jobs for croppers and tenant farmers (Cobb 2008; Griffin 1982; Auerbach 1966, pp. 3–74; Grubbs 1971).

The STFU had more than 35,000 members by 1938. Though the organization lasted till about 1989, it was ineffective from the early 1940s onwards. Ideological differences over whether to join the Congress of Industrial Organizations or the Communist Party, debates over whether blacks should leave the organization, anti-communist infiltration, infighting, the emergence of the mechanical cotton pickers and tractors, and the Great Migration made the organization lose focus and influence (Cobb 2008; Griffin 1982; Auerbach 1966, pp. 3–74; Grubbs 1971).

Cooperatives in the Civil Rights Era and Beyond

The civil rights era ushered in a period of renewed emphasis on black farmer’s cooperatives. Through the cooperatives, blacks pooled their resources to purchase farm supplies in bulk, share equipment, identify supply chains, expand their value-added operations, and consolidate their transactions to limit exposure to hostile merchants. Some merchants denied blacks known to be members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) access to supplies, credit, and markets. As a result, black farmers collaborated with each other to establish alternative supply chains for their produce. For example, in 1956, black farmers in Clarendon County, North Carolina formed the Clarendon County Improvement Association to counter the discrimination they faced because of their membership in the NAACP. When local bankers stopped issuing credit to members of the Association, the NAACP and the United Automobile Workers helped members secure other funding. Black farmers also formed the Grand Marie Vegetable Producers Cooperative, Inc., in Louisiana in 1965 to counteract racism and get their produce to market (Reynolds 2002, pp. 2, 10–11; Daniel 2000, p. 247; Marshall and Godwin 1971, p. 51).

The National Black Farmers Association has argued that the lack of access to a broad variety of seeds puts them at a disadvantage. The group has spoken out against what it sees as the monopoly that Monsanto has on seeds. The National Black Farmers Association—that has about 80,000 members—also publicly opposed Monsanto’s acquisition of Delta and Pine Land, one of the nation’s largest cotton seed companies. Members of the National Black Farmers Association allege that they are unable to purchase seeds locally because of their stand against Monsanto hence they have to drive to different states to purchase the seeds needed for their farms (Boyd 2009; National Black Farmers Association 2007).

Similarly, one of the largest black cooperatives, the South West Alabama Farmers Cooperative Association, was boycotted by white merchants and harassed by politicians. This cooperative was formed in 1967. As black cooperatives proliferated, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, also founded in 1967, was formed to serve as an umbrella group to organize the myriad of farmers’ cooperatives, credit unions, and related community-based organizations. Within 2 years of its founding, the Federation had 24 agricultural cooperatives with 5982 members in its fold. By the 1970s, 50 agricultural cooperatives operated under the aegis of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives. The Federation merged with a sister organization, the Emergency Land Fund, to better position itself to deal with the crisis of diminishing land ownership among blacks. Today, the Federation has more than 70 cooperative groups and a membership of over 20,000 families (Voorhis 1975, p. 212; Marshall and Godwin 1971; Reynolds 2002, p. 11; The Federation of Southern Cooperatives 2007, 2017).

Black Farmers Today

In 2012, the agriculture census reported that the country’s 46,582 black farm operators accounted for 1.5% of the total farm operators. This number should be interpreted with caution because prior to 2002, the agriculture census collected information on only one farm operator (the principal operator) per farm. Since 2002, the census collects information on multiple farm operators when more than one person operates a farm. However, during the period (2002–2012), the new data collection method has been in place, the total number of black farm operators has increased by 10,212; this represents a 28% increase over this period (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2004, pp. 54–55, 2009, pp. 58–64, 2014, pp. 58–65).

Nationwide, black farmers are older than others and still operate small farms. While the average American farm is 434 acres in 2012, the average size of black-operated farms is 125 acres. The average value of sales on black-operated farms is $36,052 while the nationwide average is $187,097. Table 2 shows that unlike their predecessors, most contemporary black farm operators own the land they farm. That is, 67.8% of the black operators are full owners of the land they farm and this accounts for 45.7% of the acreage farmed by blacks in 2012. Moreover, black tenant farmers are now playing only a minor role in farming (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2014, pp. 58–65). Overwhelmingly, black farms are owned by an individual or family; 89.6% of black-operated farms fit this description in 2012. While the percentage of black farms operated by corporations has fluctuated since 1997, the percentage operating as cooperatives/estates/trusts have increased from 0.9% in 1997 to 1.4% in 2012 (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2014, p. 63, 2009, pp. 58–64, 1999, pp. 25–26).

Contemporary black farmers have moved away from cotton and tobacco production and have diversified what they produce. Hence in 2012, 17,037 black farms were cattle ranches, 7324 grew sugarcane, 2839 farmed oilseed and grain, almost 2000 grew vegetables and melon, and more than a thousand reared goats and sheep, or operated greenhouses and nurseries. In contrast, that year there were only 201 black-operated cotton farms and 138 black-operated tobacco farms (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2014, p. 62).

The Lawsuit Against the United States Department of Agriculture

Allegations of Discrimination Against Black Farmers

Black farmers have difficulty obtaining credit and this is at the crux of their grievances against the USDA. Between 1984 and 1985, for instance, the USDA lent about $1.3 billion to 16,000 farmers but only 209 of them were black. Black farmers were also affected by falling crop prices and high interest rates charged on loans. When farmers were unable to repay their loans, banks foreclose on their property. Not only were black farmers systematically denied disaster relief aid and loans offered to white farmers, it took an average of 60 days to process loan applications for white farmers while it took about 220 days to process loan applications for black farmers. Moreover, some of the loans made to black farmers were not approved till late in the growing season. Blacks also received about $21,000 less than white farmers in loans even though they managed similarly sized farms (Merem 2006, pp. 88–92; Rural Coalition 2001; Goffe 2002, p. 43; Daniel 2013; Pigford et al. v. Glickman 1998; Pigford v. Glickman and Brewington v. Glickman 1999; Congressional Record 2010: S6836-S6837). A study of 348 Farm Service Agency loan applications in Georgia between 1999 and 2002 found that 57.6% of loan applications were approved compared to 39.2% of the loans of nonwhite borrowers. However, the study found that race was not a significant predictor of loan approval in multivariate models (Escalante et al. 2006, pp. 61–75). The decline in the number of black farmers caught the attention of congress and led to an investigation into the cause of the decline. Black farmers identified the USDA as an agency that discriminated against them through the programs it ran and the way the agency responded to complaints. Blacks filed suit against the agency in 1997; the case, Pigford v. Glickman, was brought by 401 black farmers alleging that the USDA discriminated against them in the way they administered farm programs. The farmers also alleged that the agency failed to investigate complaints properly.Footnote 7

The programs in question were those administered by the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service and the Farmers Home Administration. Together, the two programs administered loans and subsidies such as price support loans, disaster relief payments, and farm ownership and operating loans. The two programs ran until 1994 when they were folded into the Farm Service Agency. Though the programs operated with federal funds, the funds were controlled and disbursed by county committees. The county committees made decisions on who should get funding, how much they should get, and how expeditiously requests were processed. If farmers’ requests were denied, they can appeal to a state committee and after that to a federal review board. Farmers who felt the denial of their application was racially motivated could file a complaint with the Secretary of the USDA or with the Office of Civil Rights Enforcement and Adjudication (Pigford v. Glickman 1998, 1999). Despite the fact that the USDA vested so much power in the hands of the county committees, these entities did not reflect the racial make-up of the communities they served. Though the Southeast region has the largest concentration of black farmers, in 1996 only 28 or 1.1% of the 2469 county commissioners in the region were black. In the Southwest region, 0.3% of the county commissioners were black. In fact, there were a total of 37 black county commissioners out of a total of 8147 nationwide.Footnote 8

The black farmers’ law suit alleged that the county committees denied loans and disaster relief to blacks while those for similarly situated whites were approved. It was also alleged that the county committees took longer to process loans for blacks than for whites. Though farmers could send a complaint to the USDA, the agency dismantled its Office of Civil Rights in 1983 and from that time onwards complaints were not processed, investigated, or forwarded to the appropriate agency. As a result, farmers who filed complaints either got no response or a cursory notification that their request was denied. At the same time, farms were being foreclosed on despite the fact that complaints were filed and not processed. In 1997, the Office of Inspector General of the USDA acknowledged that the agency had a large backlog of complaints of discrimination that had not been processed, investigated, or resolved (Pigford v. Glickman 1998, 1999).

The Consent Decree

A Consent Decree between the USDA and plaintiffs was reached on January 5, 1999. The litigants in two law suits—Pigford v. Glickman and Brewington v. Glickman—were consolidated into one group of class action plaintiffs. The time of the alleged discrimination was limited to those occurring between January 1, 1981 and December 31, 1996 and farmers who were not a part of the original law suit but who met the criteria outlined above were allowed to join the class (Pigford v. Glickman 1998; Pigford v. Glickman 1999). If they chose the path that required the lowest burden of proof (Track AFootnote 9), farmers filing successful claims were awarded $50,000, plus an additional $12,500 to pay the taxes owed on the settlement (Roth 2004).

The number of black farmers making claims ballooned quickly. In 2004, the court-appointed monitor Randi Roth, testified before the House Judiciary Committee that there were 22,369 eligible claimants in the case. However, thousands more—claiming that extraordinary circumstances prevented them from filing on time—filed claims through the late claims process. In all, 96,189 claims were filed. As of 2009, there were 22,721 eligible claimants; 99% of these were track A claims. In all, 69% of the claims were approved. A total of $1,002,471,686 was paid out under track A by 2009 (Roth 2004; Office of the Monitor 2009).

Continued Legal Battles Between the USDA and Black Farmers

Despite the settlement, the relationship between the USDA and black farmers is characterized by acrimony and distrust. Since 2000, more than 14,000 complaints have been filed with the agency (Vilsack 2009). There was also an ongoing controversy over what to do about the thousands of late claimants in the Pigford case that are considered ineligible. This was addressed somewhat in the 2008 Farm Bill that allowed for the late claims to be reviewed to ascertain if any qualified to be included in class action group. The bill also included a $100 million appropriation to settle the cases in addition to a provision to allow for more funds to settle cases if needed. In 2008, the National Black Farmers Association filed a lawsuit against the USDA on behalf of 823 black farmers (USA Today 2008; Hagstrom 2009). In 2010, the congress approved an additional $1.25 billion to settle approximately 61,000 additional discrimination claimsFootnote 10 that had been filed by black farmers not covered by the Pigford v. Glickman settlement (Department of Justice 2010; Congressional Record 2010: S6836-S6837).

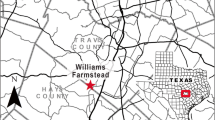

Black Farmers in Michigan

Black farmers in northern states like Michigan are often overlooked because they comprise a small portion of the nation’s black farmers,Footnote 11 and they make up a modest share of the farmers in their state. Nonetheless, Michigan is important and interesting state to examine black farmers’ experiences because of the complex relationships that has evolved over time between southern black farmers, black rural Michigan farmers, and black urban farmers in the state. The relationships are both competitive and collaborative and are rooted in kinship ties and culture, as well as the rhetoric of black empowerment, food sovereignty, and environmental justice.

Historical Context

Blacks have been farming in Michigan since the antebellum period. The earliest black farmers were either recruited to Michigan or followed the Underground Railroad to the state. A steady stream of blacks settled in the southeastern and southwestern portions of the state. Records from Pittsfield Township (near Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti) indicate that abolitionists collaborating with the Underground Railroad settled in the township in the 1820s. Blacks seeking their freedom settled in the area on the Old Sweet Briar Farm located on or nearby Jacob Aray’s property (Richards n.d.).

Some of Southwest Michigan’s early black residents worked for their Quaker benefactors as share croppers and in other capacities till they amassed enough money to purchase their own land. Quakers, some of whom were farmers in places like North Carolina, moved to Michigan to establish farms in the early nineteenth century. The Quakers were ardent abolitionists, hence Cass County—especially Calvin Township, Vandalia, and Ramptown—became strongholds of Underground Railroad activities (Ben and Wilson 1986, p. 22; Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History n.d.).

Enoch Harris and his wife, Deborah, were the first black farmers to settle in Kalamazoo County; they did so around 1830. The Harrises, who were originally from Virginia, settled in Knox County, Ohio in 1813 then moved to Michigan to live on an 80-acre farm. The Harrises, who brought apple seeds with them, is said to have established the first apple orchard in Oshtemo Township and Kalamazoo County. By 1860, the Harrises raised horses, cows, sheep, and pigs. They also grew wheat, Indian corn, oats, peas and beans, potatoes, barley, hay, and orchard crops. The family owned about 2000 acres of land by the 1880s (Kalamazoo Morning Gazette 1902; Santamaria 2002; Praus 1960, pp. 61–66; Ben and Wilson 1986, p. 23).

Black farmers in Calvin Township in the southwestern tip of Michigan trace their lineage in the area to 1839 and the free blacks who traveled from North Carolina to settle in the area. Some blacks moved with Quakers and settled in Southwest Michigan. A former slave, Lawson, arrived in Calvin Township in 1836; he took up farming. Another runaway slave, Jesse Scott, who arrived 2 years later, raised tobacco once he settled in the township. Bill Lawson’s great-great-great-grandfather, Gault, arrived in Southwest Michigan from North Carolina in 1838 or 1839. Another 43 free blacks who settled in Cass County between 1845 and 1846 purchased farmland. At one point, blacks farmed as much as 38% of Calvin Township; some of their farms were more than 200 acres in size. For instance, Littleberry Stewart owned 240 acres of land in the township during the 1860s (Worthington 1987, p. 3; Ben and Wilson 1986, p. 24; Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, n.d.; Thierry 1997, pp. A1, 10).

Black Michiganders embraced the opportunity to own land and operate their own farms. As one black farmer put it, “…it was easier to get along by farming one’s own land than it was to manage by working for meager wages in the white man’s field…but just as importantly, land was a symbolic goal of freedom…a necessary and complimentary part of becoming equal in society.” Despite being recruited to settle and farm in Michigan, once blacks arrived in the state, they faced similar forms of discrimination meted out to blacks elsewhere. There were relegated to marginal lands and had difficulty receiving financing. Consequently, blacks did not have an opportunity to farm the best lands in Michigan (Quote copied from Ben and Wilson 1986, pp. 23–24). Notwithstanding, black farmers settled in throughout the southern part of the state. They could be found in small communities in Covert, Idlewild, Benton Harbor, as well as in Mecosta, Isabella, and Montcalm counties (Old Settlers Reunion 2017).

By 1900, there were 626 black-operated farms in Michigan; 75.4% of these were owner operated. That year, blacks farmed a total of 38,259 acres in Michigan. The average black-operated farm was 61.1 acres (DuBois 1904, pp. 69–98, 296–302, 332). Blacks continued to move to Michigan during the Great Migration as cities like Detroit—with its booming auto plants—were attractive destinations. The black migrants brought to Michigan agricultural skills they had honed on southern farms.

Blacks from Baltimore and New York were recruited to purchase large tracts of abandoned farmland “of good quality” in Michigan in the 1920s. One article noted that blacks were being tricked into purchasing land unfit for agriculture. To prevent swindling, the state of Michigan created a Division of Negro Welfare and Statistics in the Department of Labor and Industry to investigate complaints (The Baltimore Afro-American 1925: A8; The New York Amsterdam News 1926, p. 15).

Blacks found it challenging to obtain credit to purchase land and develop farms in Michigan.

This was so ubiquitous that it made national headlines when Clarence Haines of Calvin Township in Southwest Michigan obtained a loan from a black-owned lending agency that was insured by the Farmers Home Administration of the USDA in 1949. This might have been the first government-insured loan made to a black farmer in Michigan. Upon receiving the check of $5500 from the Supreme Liberty Life Insurance Company of Chicago, Mr. Haines commented, “…My only hope is that this kind of help can reach a lot of other folks like me” (Quote copied from The Chicago Defender 1949, p. 4; New York Times 1949, p. 63).

However, the number of farms operated by blacks in Michigan and the number of acres they farm declined precipitously during the twentieth century. The loss of black-owned farmland accelerated between 1920 and 1970. The disposal of heirs’ property played a role in the decline as the children of black pioneers sold off farmland. Roughly 12,545 acres were lost this way. Heirs sold the property because of high taxes, limited profits, and legal malfeasance (Ben and Wilson 1986, p. 25).

As the loss of farmland became more noticeable, civil rights and black power activists sought to stem the tide by acquiring land to farm collectively. Land acquisition was also seen as a mechanism for reducing food insecurity in black communities, striving toward food sovereignty, controlling the means of production and distribution of food, and furthering the economic development of blacks. Black nationalists in the Nation of Islam and other groups also saw land ownership as a means of furthering black empowerment. Consequently, the Nation of Islam tried to purchase 3600 acres of land in rural Alabama. This infuriated the Klu Klux Klan and other whites opposed to black land ownership.Footnote 12 Despite the opposition in Alabama, the Nation of Islam acquired large tracts of land not only in Alabama, but in Georgia, Illinois, and Michigan (Reid and Bennett 2012, pp. 248–249; Waldron 1969; Associated Press/New York Times 1970; United Press International 1969).

It was during this era that young Wilbur Minisee of Niles, Michigan decided he wanted to farm. In 1968, Minisee, then 15 years old, secured a $300 loan with the aid of his father, and started farming on 10 acres. A decade later, he operated 600 acres of farmland. Minisee’s ancestors were free blacks who moved from Upstate New York to Southwest Michigan in the 1850s (U.S. Department of Agriculture 1980; Thierry 1997, pp. A1, 10).

The twin practices of segregating black farmers in particular locales and forcing them to farm on undesirable, hazard-prone land occurred in Michigan too. The practice of redlining minority urban neighborhoods, refusing to grant home loans to residents living in such areas, and the refusal to sell such residents property in desirable white neighborhoods was mimicked in the agricultural sector (Taylor 2014). As a result, black farmers had difficulty purchasing land in desirable areas and could not get funding to develop their existing acreage (Townsend 2016). The Mitchells are a case in point. Four generations of them operate an organic blueberry farm in Grand Junction (Van Buren County) that produced more than 10,000 of blueberries in 2015. But when they tried to purchase land in the late 1960s, they were forced to buy a swampy area. They had to truck in a lot of dirt to fill in the area before they could plant on it. Black farmers in Michigan report that they find it virtually impossible to purchase land with highly rated soil and they were forced to purchase farms beside one another (Townsend 2016).

The Contemporary Context

As Table 3 shows, there were only 110 black farm operators in Michigan in 1997 and they accounted for 0.2% of the farm operators in the state (U.S. Department of Agriculture 1999). This marked the nadir of black farming population in Michigan as well as the nation. But the following year would be pivotal. In 1998, the National Black Farmers Association organized a National Black Farmers’ Conference.Footnote 13 The Michigan Coalition of Black Farmers, the state chapter of the National Black Farmers Association, hosted the conference. Hence in May of 1998, more than 1000 black farmers from 29 states descended on Detroit for the conference that was organized around the theme of “Saving the Black Farmer.” At the time, black farmers were losing an estimated 9000 acres of farmland per week because of foreclosures. The conference focused on strategies for influencing federal policies, halting the land loss plaguing black farmers, promote urban agriculture amongst blacks, and strengthen institutional infrastructures to help black farmers work collectively to maximize their impact (New York Beacon 1998, p. 10; Stone 1998: A1). A month later, the Michigan House and Senate passed a resolution to end years of discrimination in the state against black farmers (Amick 1998: A4).

The Michigan Coalition of Black Farmers helps black farmers to collaborate with each other, promote the sale of their produce to retailers, and market the farmers. In August 1998, the Michigan Coalition of Black Farmers joined forces with the Federation of Southern Cooperatives and the Nation of Islam (founded in 1930 in Detroit) to work out an agreement with Eastern MarketFootnote 14 in Detroit to sell food grown and distributed by blacks. This allowed black Detroiters to support black farmers in the South since the Nation of Islam planned to sell food grown on its Albany, Georgia farm and the Federation of Southern Cooperatives purvey food grown by black farmers all over the South to consumers in Detroit (Long-Bey 1998: A1; 1999: A1; Stone 1998: A1). Blacks viewed the agreement among themselves as mutually beneficial because from it southern farmers got access to a northern market while northern farmers got the branding, support, and resources of nationally recognized groups and important actors in farming and political issues.

The following year, Hank Reed, president of the Michigan Coalition of Black Farmers and owner of Metro Foodland Supermarket,Footnote 15 reported that produce grown by southern black farmers was being sold in his and the other black-owned Foodland Supermarket in Detroit. Reed and his collaborators were being intentional about building a supply chain in which produce from southern black-owned farms was being trucked to and sold in black-owned supermarkets to black customers. Reed assessed the initiative this way, “We are setting up an opportunity for black folk to help themselves.” He continued, “The farmers are black, and the transportation system and supermarket[s] are black.” James Hooks, owner of the second participating Foodland Supermarket explained further. He said, “…black people have to build vertical enterprises controlled by blacks from bottom to top” (Long-Bey 1999: A1).

A similar partnership focused on black economic empowerment, food sovereignty, and increased consumption of healthy foods was attempted with the launch of Freedom Foods in Detroit in 2002.

Freedom Foods sought to facilitate the sale of produce from black farmers in Michigan and the South.

The organizers took this approach because they argue that grocery store owners rarely purchase products from black farmers. The partnership also materialized because a Detroiter with farms in Georgia wanted to sell the produce grown in Georgia in Detroit (Akwamu 2002: B1).

There has been a resurgence of black farmers in Michigan. Since 2002, the number of black farm operators has increased from 243 to 356. In 2012, black farm operators account for 0.5% of the farm operators in Michigan (USDA 2014). Despite this milestone, Michigan’s black farmers continued to seek compensation for discrimination suffered at the hands of the USDA between 1981 and 1996. As a result, black farmers collaborated with the Land Loss Prevention Project, a North Carolina-based nonprofit, to file claims by the 2012 deadline. Of the roughly 89,000 claims filed, 1456 were from black farmers in Michigan (Lersten 2012). Michigan’s black farmers were not a part of the original law suit.

Of the 52,194 farms in the state in 2012, 271 were operated by blacks (see Table 4). That year, there were a total of 356 black farm operators in the state and together they farmed a total of 19,369 acres. All told 9,948,564 acres are farmed in Michigan in 2012. Black-operated farms tended to be smaller than others in the state. While the average size of black-operated farms is 71 acres, the state-wide average for farms is 191 acres (USDA 2014). Despite the resurgence of farming by blacks, in 2012 Michigan’s black farmers were farming just over half the acreage they did in 1900. So, what is most commonly found on Michigan’s black-operated farms? Most often, these farms are used to grow forage, oilseed and grain, berries, soybeans, corn, fruits, and vegetables. Their top livestock inventory items are horses and ponies, laying hens, cattle and calves, and bees (USDA 2009, 2014).

Michigan’s rural black farmers have worked closely with black urban growers to establish farms in cities like Detroit and Flint. Food sovereignty and self-empowerment through food production are themes that unite them. As Barbara Norman, whose family has been farming since the 1930s, said before delivering the 2014 keynote address to the Black Farmers and Urban Gardeners Conference in Detroit, “He who owns the land makes the rules.” Norman operates a 53-acre blueberry farm in Covert, located in Southwest Michigan (Blount-Dorn 2014: A8). Kadiri Sennefer agrees. She says of D-Town Farm, “It’s a self-determination project. We’re not looking for anyone to do it for us. We come out here and do the work ourselves. We dig for ourselves and we do for ourselves” (Michigan Public Radio 2012).

Researchers have documented the extent to which food sovereignty, food security, and empowerment have infused the discourses of Michigan’s black urban growers (Taylor and Ard 2015, pp. 102–133; White 2010, pp. 189–211; White 2011a, pp. 406–417; White 2011b, pp. 13–28). For instance, Bianca Danzy, a student farming at Earthworks in Detroit says, “Growing your own food is self-determination, food that you put in the ground, you grew and then prepared…[it] nourishes you and detaches you from the need to go and pay a food bill” (Public Radio International 2016). Michigan’s black urban growers have also articulated these themes as well as the challenges they face acquiring land on which to grow (Yakini 2010, 2013: A10).

Despite the publicity surrounding discriminatory lending practices, access to reliable and adequate financing for farming activities continue to bedevil Michigan’s black farmers. A recent study the farmers’ perceptions of credit availability found that black farmers were reluctant to use government loans to finance their operations and only turn to this source as a matter of last resort. This is by design; the Farm Service Agency provides financial assistance to farmers only after they have exhausted other credit options. Michigan’s black farmers are cautious about using Farm Service Agency loans because of a history of discrimination against black borrowers and lack of outreach to them. A farmer in the study explains why his experiences lead him to bypass the Farm Service Agency. He told the researchers, “I went to production credit…he’s never loaned money to a Black man so it ended up that I didn’t get the money…now I just don’t bother with it.” Another farmer expressed frustration with the limited information that black farmers receive. He said of the agency, “…they’re not forthwith with information when you go in there…the information is not really made available to us [African-American farmers] (Quote copied from Tyler et al. 2014, pp. 232–251; Escalante et al. 2006, p. 62). In spite of these challenges, Michigan’s black farmers exhibit great fortitude. In 2012, 59.1% of them had operated their farms for 10 years or more (USDA 2014).

Discussion and Conclusions

Cooperatives and Community-Based Organizations

Blacks have farmed in America for four centuries, yet for that entire time, they have struggled to own and retain farmland. This is the case because a variety of institutional mechanisms were used to restrict black landownership. Moreover, once blacks gained ownership of farmland, systematic discrimination by government and non-governmental sources precipitated land loss. Discrimination took several forms, namely separate and unequal policies and services, segregation, isolation, inadequate resources, forcing blacks to live in hazardous places. In response, blacks have founded several institutions to help ameliorate their situation.

For more than a century, blacks have used the cooperative model to help them retain farmland. Today, cooperatives still play important roles in farm preservation and vitality in the black community. In this vein, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives has been working with more than 25,000 low-income families in more than 100 communities throughout the South. In 1993 and 1994 alone, the multi-racial organization helped 200 families retain 17,500 acres of land they would have lost otherwise (Zippert 2002; Merem 2006, pp. 88–92). Another organization, the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, is working with families to educate them about heirs’ property and to help them navigate the legal hurdles involved in resolving the issues arising with such property (Southern Coalition for Social Justice, 2009).

Other organizations focused on preventing land loss have emerged. Foremost among them, the Land Loss Prevention Project, founded in 1982 by the North Carolina Association of Black Lawyers, provides support to financially distressed farmers in the state and elsewhere. The group provides legal help, as well as help with policy making and promoting sustainable agricultural practices. They have provided technical assistance and legal support to more than 20,000 people (Land Loss Prevention Project 2009).

Another organization, the Black Family Land Trust, was founded in North Carolina in 2004 with the mission of combining traditional land trust tools with community economic development to help preserve black farms. It is a coalition of advocacy groups working on the preservation of black landownership that includes the Land Loss Prevention Project and the Federation of Southern Cooperatives (Black Family Land Trust 2002). Other groups such as the Congressional Black Caucus have helped black farmers by sponsoring and supporting legislation in Congress. The Rural Coalition and the National Family Farm Coalition have also been involved in initiatives to prevent the loss of farmland amongst blacks.

The USDA was not alone in its treatment of blacks. Discriminatory actions in the USDA mirror those of other federal and local agencies charged with housing and financing, education, and general welfare. The fear of racial mixing and opposition to racial equality drove agency personnel to segregate farms and deliver inadequate financing and resources to blacks. This was similar to the way housing agencies segregated urban and suburban communities and either denied credit or influenced banks to withhold credit from blacks (Taylor 2014). Education departments denied blacks the right to equal education when they segregated schools also.

Heritage Tourism and Historic Preservation

In response, some black communities and black land owners have been exploring the idea of using heritage tourism and historic preservation as mechanisms for protecting black land ownership. The Penn Center located on St. Helena Island, South Carolina offers an example of a rural site that uses black heritage as the cornerstone of its farm-based preservation efforts. The Penn Center preserves its land, waterfront, trails, the Gullah language spoken by slaves, crops planted by them, the culture of the Gullah people, its historic school house built by freed slaves, museum, art, as well as its famed conference center and dorms that served as the meeting place for civil rights activists (Penn School 2017). The 40-acre Freewoods Farm, located in Burgess (Myrtle Beach), South Carolina replicates life on a nineteenth century animal-powered African American farm. Freewoods has a museum, wetlands preserve, and a main street (Freewoods Farm 2017). The 500-acre Smith Family Farm Park, located in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, relies on visits by black recreationers to supplement their farm income. The farm has been in the family for three generation and the five Smith brothers grow grain, raise cattle, and propagate fish in aquaculture ponds. They have converted 41 acres of the farm into a recreational park that is used primarily by black visitors for family reunions, horseback riding, and motorcycle club gatherings. The 14-acre catfish pond, horse trails, and all-terrain vehicle trails are popular (Freeman and Taylor 2010, pp. 267–268).

Responses in Michigan

There are efforts underway in Michigan to preserve black farming traditions. The Michigan Food and Farming SystemsFootnote 16 Women in Agriculture program in Genesee County runs a 3-acre farm that trains blacks and women of many racial and ethnic backgrounds to become farmers. Earthworks Urban Farm collaborates with the Capuchin Soup Kitchen to train aspiring black agriculturalists on their 2.5-acre farm in Detroit (Boehm 2017).

Black-operated farms such as D-Town Farm also train black youths and community members to farm. D-Town is a combination farm and food-buying cooperative operated by the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (White 2010, 2011a; Yakini 2010, 2013; Taylor 2000, 2014; Taylor and Ard 2015).

The Southeast Michigan Producers Association (SEMPA) is a cooperative located in Sumpter Township that serves small- to medium-sized farms. Most of the members are black and they live in the Detroit to Ann Arbor corridor of the state. They aggregate their produce, certify, and market black farmers to help them gain access to urban markets, and schools in the area. The cooperative also seeks to reduce land loss among black farmers. There are about 50 black farmers in the region covered by SEMPA (Boehm 2017; Michigan Public Radio 2012; Barry 2013). SEMPA collaborates with black farms, CanStrong Food Service Management, and the state’s Farm-to-School Program to provide fresh fruits and vegetables to local schools (Tell Us USA News Network 2015).

The relationships forged between southern black cooperatives, Michigan’s black farmers, and Detroit’s consumers still endure. However, these relationships require further study to assess their future viability. This is particularly true since the city now has a robust urban agriculture sector. To strengthen their economic position, Michigan’s black farmers need to continue seeking new outlets for their produce.

They could look beyond Detroit to other cities within Michigan or to neighboring states. Black farmers can also expand their Farm-to-School operations and develop partnerships with restaurants, hospitals, and colleges and universities, etc. Black farmers in Michigan and around the country have adapted to changing social, political, and economic conditions in the past. They are taking steps to help them survive in the current agricultural climate.

Notes

The Freedmen’s Bureau lasted until 1869. The Bureau focused on negotiating labor contracts between plantation owners and freed slaves (Reynolds 2002, p. 3).

The Farm Service Agency traces its roots to 1933 and New Deal programming. The USDA created the Farm Security Administration in 1935 (this was originally called the Resettlement Administration). The agency was renamed the Farm Service Agency in 1937 (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2017).

Between 1882 and 1930, 1663 blacks were lynched in the Cotton Belt alone and 1299 were executed. About 90% of the people lynched and executed in the South were black (Tolnay and Beck 1991, p. 27, 1990, pp. 347–370). Though work by Johnson (1923), pp. 272–274 and Fligstein (1981), call into question the relationship between lynchings and black out-migration, Tolnay and Beck (1991), pp. 20–35 found such a relationship existed.

The outbreak, which began in Texas in 1898, spread eastwards. Thousands of agricultural workers lost their jobs in the wake of the devastation (Marks 1991, p. 37).

Local elites created New England village improvement societies as part of the rural beautification and farmscaping movements (Taylor 2016, pp. 257–289).

Claims could be made through one of two tracks. Track A had a low burden of proof. This track also allowed for debt and injunctive relief. There was no discovery and proof could consist of claimants identifying a similarly situated white farmer who was treated more favorably. Track B had no cap on awards, but a higher standard of proof was needed and trial was required. Plaintiffs had to demonstrate that they were actually discriminated against and suffered actual damages. If claimants prevailed they would get actual damages, debt and injunctive relief (Pigford v. Veneman 2002; Roth 2004).

Farmers had until May 11, 2012 to file claims (Lersten 2012).

In 2012, 90% of black farmers live in 12 southern states (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2014).

The Klu Klux Klan, founded in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1865, spread rapidly to other parts of the South (Hinson and Robinson 2008, p. 286). Klan violence made it virtually impossible for blacks to acquire land in Georgia in 1876. Small-scale white land owners in Mississippi, strongly opposed to black landownership, directed their ire towards blacks (Du Bois 1901, p. 669; Fisher 1973, p. 485).

The first conference of this nature was organized by Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee in 1892. The conference—attended by about 400 black men—was titled, Farmers’ Conference for Blacks. It focused on land ownership for blacks and crop diversification. This is still an annual event. When George Washington Carver joined the faculty at Tuskegee, he organized monthly “Farmer’s Institutes” to discuss agricultural issues with black farmers (Ross 2013; Bitter Harvest 1999; Ferguson 1998, p. 36; Hersey 2006, pp. 246–247).

Eastern Market has been in operation since 1891. The 43-acre market is the largest historic market district in the U.S. (Encyclopedia of Detroit 2017).

At the time, two of Detroit’s 28 Foodland Supermarkets were black-owned and independently operated (Long-Bey 1999: A1).

The Michigan Food and Farming Systems (2014) has a multicultural farmers program that is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

References

Akwamu, K. (2002). Feeding ourselves: black farmers appeal to community with new business model. Michigan Citizen. November 16. P. B1.

Amick, M. (1998). Resolution passed to help Michigan black farmers. New Pittsburgh Courier. June 3. P. A4.

Anderson, J. D. (1978). The southern improvement company: northern reformers’ Investment in Negro Cotton Tenancy, 1900-1920. Agricultural History, 52, 114–124.

Associated Press/New York Times. (1970). Poison is suspected in death of 30 cows on a muslim farm. March 16. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/1970/03/16/archives/poison-is-suspected-in-death-of-30-cows-on-a-muslim-farm.html.

Auerbach, J. S. (1966). Southern tenant farmers: socialist critics of the new deal. Labor History, 7, 3–74.

Barry, J. (2013). A rural Haven in Southeast Michigan. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, Michigan Good Food Center. December 1. Available at: http://www.michiganfood.org/news/a_rural_haven_in_southeast_michigan.

Ben, C., & Wilson, N. K. (1986). Economic development: land, pride and independence. The black farmer of Southwest Michigan, 1840-1930. Negro History Bulletin, 49(2), 2226.

Bennett, L. (1993). The shaping of black America: the struggles and triumphs of African-Americans, 1619–1990s. New York: Penguin Books.

Berlin, I. (1998). Many thousands gone: the first two centuries of slavery in North America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bitter Harvest. (1999). How the system ruined black farmers. February 7. Available at: http://revcom.us/a/v20/990-99/993/bfarm.htm.

Black Family Land Trust. (2002). Black family land trust: working to preserve African American resources through land ownership. Accessed at: http://www.farmland.org/programs/states/nc/NorthCarolinaBFLT.asp.

Blount-Dorn, K. (2014). Black farmers and urban growers promote power and sovereignty. Michigan Citizen. October 12. P. 8.

Boehm, J. W. (2017). Michigan’s women and minority farmers are gaining ground. Farm flavor. Available at: http://www.farmflavor.com/michigan/michigans-womenminority-farmers-gaining-ground/.

Boyd, J. W. (2009). Protecting our black farmers. Los Angeles Wave. July 31.

Breen, T. H. & Innis, S. (1980). Myne owne ground: race and freedom on Virginia’s eastern shore, 1640–1676. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bullard, R. D. (Ed.). (1993). Confronting environmental racism: voices from the grassroots. Boston: South End Press.

Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. n.d. “Cass County, Michigan.” Available at: http://ugrr.thewright.org/media/Pdf/Cass_County_Communities_UGRR_Final_1.pdf.

Cobb, W. H. (2008). Southern tenant farmers union. The encyclopedia of Arkansas history and culture. Little Rock, AR: Central Arkansas Library System. Available at: http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=35.

Congressional Record. (2010). Pigford settlement. 156(118), S6836–S6837.

Daniel, P. (2000). Lost revolutions: the south in the 1950s. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Daniel, P. (2007). African American farmers and civil rights. (Pigford v. Glickman). Journal of Southern History, 73(1), 3–27.

Daniel, P. (2013). Dispossession: discrimination against African American farmers in the age of civil rights. Durham: University of North Carolina Press.

Department of Justice. (2010). Department of Justice and USDA announce historic settlement in lawsuit by black farmers claiming discrimination by USDA.” Washington, D.C.: Office of Public Affairs. February 18. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justiceand-usda-announce-historic-settlement-lawsuit-black-farmers-claiming.

Drake, St. C. & Cayton, H. R. [1945] 1993. Black metropolis: a study of Negro life in a Northern City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1901). The Negro landholder in Georgia. Bulletin of the Department of Labor. #35. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1935). Black reconstruction in America: 1860–1880. New York: Atheneum.

DuBois, W. E. B. (1904). The negro farmer. Negroes in the United States. Prepared in conjunction with the U.S. Census Bureau. Bulletin #8. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Dyer, J. (2006) Kinship, stability and African American land loss: examining implications of heir property in Alabama’s black belt. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Rural Sociological Society. Louisville, KY. August 10.

Encyclopedia of Detroit. (2017). Eastern market historic district. Available at: https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/eastern-market-historic-district.

Escalante, C. L., Brooks, R. L., Epperson, J. E., & Stegelin, F. E. (2006). Credit risk assessment and racial minority lending at the Farm Service Agency. Journal of Agriculture and Applied Economics, 38(1), 61–75.

Ferguson, K. J. (1998). Caught in “no Man’s land”: the negro cooperative demonstration service and the ideology of booker T. Washington, 1900-1918. Agricultural History, 72, 33–54.

Fisher, J. E. (1973). Negro farm ownership in the south. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 63, 478–489.

Fligstein, N. (1981). Going north: migration of blacks and whites from the south 1900–1950. New York: Academic Press.

Foner, P. S. (1980). History of black Americans: from Africa to the emergence of the cotton kingdom. New York: Oxford University Press.

Franklin, J. H., & Moss Jr., A. A. (1994). From slavery to freedom: a history of African Americans. New York: McGraw Hill.

Freeman, O. L. (1965). Racial bias in working of U.S. farm aid criticized by federal civil rights unit. Wall Street Journal. March 1.

Freeman, S., & Taylor, D. E. (2010). Heritage tourism: a mechanism to facilitate the preservation of black family farms. Research in Social Problems and Public Policy, 18, 261–285.

Freewoods Farm. (2017). Freewoods farm. Available at: http://www.freewoodsfarm.com/index.html.

Goffe, L. (2002). African American farmers in trouble. New Nation. January. P. 403.

Goodwyn, L. (1976). Democratic promise: the populist moment in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gray, L. C. (1949). History of agriculture in the southern United States (Vol. 1). New York: Peter Smith.

Griffin, K. H. (1982). The failure of an interracial Southern rhetoric: The Southern Tenant Farmers. Union in North Carolina. Raleigh, North Carolina: Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Carolinas Speech Communication Association.

Grubbs, D. H. (1971). Cry from the cotton: the southern tenant farmers’ union and the new deal. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Hagstrom, J. (2009). Vilsack says USDA must sharpen focus on civil rights. CongressDaily. February 23.

Hersey, M. (2006). Hints and suggestions to farmers: George Washington carver and rural conservation in the south. Environmental History, 11, 239–268.

Hinson, W. R., & Robinson, E. (2008). We Didn’t get nothing: the plight of black farmers. Journal of African American Studies, 12, 283–302.

Johnson, C. (1923). How much is the migration a flight from persecution? Opportunity, 1, 272–274.

Kalamazoo Morning Gazette. (1902). ‘Enoch Harris’. Sunday, December 21.

Knapp, J. G. (1969). The rise of American cooperative enterprise: 1620–1920. Danville: Interstate Printers and Publishers.

Land Loss Prevention Project (2009). Land loss prevention project. Durham, North Carolina. Available at: https://www.landloss.org/.

Lerner, S. (2005). Diamond: a struggle for environmental justice in Louisiana’s chemical corridor. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lersten, A. (2012). Black farmers have second chance to file discrimination claims. McClatchy-Tribune Business News. March 18.

Long-Bey, J. (1998). Black farmers organize to sell at Eastern Market. Michigan Citizen, August 22, A1.

Long-Bey, J. (1999). Black farmers connect with black market. Michigan Citizen. August 21. A1.

Marks, C. (1991). The social and economic life of southern blacks during the migration. In Black exodus: the great migration from the American south. Edited by Alferdteen Harrison Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press. pp. 36–50.

Marshall, R., & Godwin, L. (1971). Cooperatives and rural poverty in the south. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Meinig, D. W. (2000). The shaping of America: a geographical perspective on 500 years of history. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Merem, E. (2006). The loss of agricultural land among black farmers. The Western Journal of Black Studies, 30, 89–102.

Michigan Food & Farming Systems. (2014). Multicultural farmers. East Lansing: Michigan Food & Farming Systems Available at: http://www.miffs.org/services/farmer_networks/multicultural_farmers.

Michigan Public Radio. Michigan Now. (2012). Black farming power. National Public Radio Broadcast. March 12.

Mitchell, T. W. (2001). From reconstruction to deconstruction: undermining black. Landownership, political independence, and community through partition sales of tenancies in common. Northwestern University Law Review. Winter: 505–511.

Mitchell, T. W. (2005). Destabilizing the normalization of rural black land loss: a critical role for legal empiricism. Wisconsin Law Review, 2: 557–615.

National Agricultural Statistics Service. (2016). Michigan agricultural statistics 2014–2015. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Michigan field office. East Lansing: Michigan State University Extension.

National Black Farmers Association. (2007). National Black Farmers Association Resolution. Bakersville: National Black Farmers Association.

New York Beacon. (1998). Black farmers hold historical conference. June 10. p. 10.

New York Times. (1949). Rise of a tenant on farm is rapid: negro prospers in Michigan aided by U.S. and insurance company of own race. March 6. p. 63.

Office of the Monitor. (2009). National Statistics regarding Pigford v. Vilsack track a implementation as of September 22, 2009. Minneapolis: Office of the Monitor.

Old Settlers Reunion. (2017). Old settlers. Available at: http://www.oldsettlersreunion.com/index.php/history.

Oliver, M., & Shapiro, T. M. (1996). Black wealth/white wealth: a new perspective on racial inequality. New York: Routledge.

Oubre, C. (1978). Forty acres and a mule: the freedmen’s bureau and black land ownership. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Partnership for Public Service (2016). Best places to work: farm service agency. Available at: http://bestplacestowork.org/BPTW/rankings/detail/AGFA#tab_demographic_tbl.

Pease, W. H., & Pease, J. H. (1963). Black utopia: negro communal experiments in America. Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

Penn School National Historic Landmark District. (2017). The penn center. Available at: http://www.penncenter.com/resources.html.

Pigford v. Glickman and Brewington v. Glickman. (1999). 185 F.R.D. 82.

Pigford v. Veneman. (2002). 292 F.3d 918.

Pigford, et al., v. Glickman. (1998). Civil action No. 97–1978. 182 F.R.D. 341.

Praus, A. A. (1960). Enoch Harris—negro pioneer. Michigan Heritage, 11(2), 61–66.

Public Radio International’s The World. 2016. Black farmers in Detroit are growing their own food. But they're having trouble owning the land. March 30. Available at: go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=STND&sw=w&u=lom_umichanna&v=2.1&id=GALE%7CA44834%207571&it=r&asid=9d637db926b8205271239b15f072f4a5.

Reid, D. A., & Bennett, E. P. (2012). Beyond forty acres and a mule: African American landowning families since reconstruction. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Reynolds, B. (2002). Black farmers in America, 1865–2000: the pursuit of independent farming and the role of cooperatives. RBS Research Report 194. Rural Business-Cooperative Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Richards, H. n.d. Old Negro burying ground – section 13, Pittsfield Township, Michigan (MI). Pittsfield Township, MI: Pittsfield Township Historical Society. Available at: http://pittsfieldhistory.org/index.php?section=sites&content=old_negro_burying_ground.

Ross, J. S. (2013). Black farmers: new markets, new hope. The Daily Yonder. April 3. Available at: http://www.dailyyonder.com/black-farmers-new-markets-newhope/2013/04/03/5743/.

Roth, R. I. (2004). Testimony before the house judiciary committee, subcommittee on constitution. Minneapolis: Office of the Monitor.

Rural Coalition. (2001). Civil rights in agriculture: decline in minority farmers. Washington, DC: Rural Coalition.

Santamaria, K. (2002). Enoch and Deborah Harris: black pioneers. Kalamazoo: Kalamazoo Public Library.

Schweninger, L. (1989). A vanishing breed: black farm owners in the south, 1651-1982. Agricultural History, 63, 41–60.

Shannon, F. A. (1968). The farmer’s last frontier: agriculture, 1860–1897. New York, NY: Harper Torchbooks.

Southern Coalition for Social Justice. (2009). Orange county heirs’ property study. Available at: http://www.southerncoalition.org/node/40.

Stone, J. (1998.) Farmers Conference: From the Ground Up. Michigan Citizen. January 31. P. A1.

Taylor, D. E. (2000). The rise of the environmental justice paradigm: injustice framing and the social construction of environmental discourses. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(4), 508–580.

Taylor, D. E. (2014). Toxic communities: environmental racism, industrial pollution, and residential mobility. New York: New York University Press.

Taylor, D. E. (2016). The rise of the American conservation movement: power, privilege, and environmental protection. Durham: Duke University Press.

Taylor, D. E., & Ard, K. J. (2015). Food availability and the food desert frame in Detroit: an overview of the city’s food system. Environmental Practice, 17, 102–133.

Tell Us USA News Network. (2015). Mich African American Farmers Team Up With SEMPA and CANSTRONG to Deliver 18K Meals a Day. May 18. Available at: http://www.tellusdetroit.com/local/Michigan-African-American-farmers-team-up-to-deliver-18Kmeals%20a-day-051815.html.

The Baltimore Afro-American. (1925). Michigan offers good farm lands: division of negro welfare say large tracts available to Negro framers. January 17. p. A8.

The Chicago Defender. (1949). Michigan farmer granted first U.S. insured Negro agency loan. March 12. p. 4.

The Federation of Southern Cooperatives. (2017). History. Available at: http://www.federationsoutherncoop.com/files%20home%20page/history.htm.

The Federation of Southern Cooperatives. (2007). “Four decades (1967–2007): historical review of the federation of southern cooperatives/land assistance fund.” Available at: http://www.federationsoutherncoop.com/fschistory/fsc40hist.pdf.

The New York Amsterdam News. (1926). Opportunities on farms in Michigan: division of Negro welfare encouraging agricultural life. October 20. p. 15.

Thierry, M. A. (1997). Farming stronghold now has few black farmers. Detroit Free Press, A1, 10.

Tolnay, S. E., & Beck, E. M. (1990). Black flight: lethal violence and the great migration. Social Science History, 14, 347–370.

Tolnay, S. E., & Beck, E. M. (1991). Rethinking the role of racial violence in the great migration. In A. Harrison (Ed.), Black exodus: the great migration from the American south (pp. 20–35). Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.