Abstract

This paper investigates origins, original languages and authors of bestselling translations on the annual Dutch Top 100 bestseller list. Considering the first fifty entries on the lists from the period between 1997 and 2019, the study aims to determine the Dutch position within the World Language System. The results show that about half of all the books surveyed are translations. These come from fifteen different source languages, although a clear majority are translations from English (73.2%). The analysis confirms the notion of a World Language System with central, semi-peripheral and peripheral languages and places Dutch among the peripheral languages. Furthermore, the study reveals strong globalisation and commercialisation tendencies in the Dutch book market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Translations fulfil an important role in local and global cultural exchange and have been an indicator of relations between nations and cultures for centuries [9, 14, 19,20,21,22]. They transmit world views, beliefs and stories from other cultures, so translations can enable and facilitate mutual understanding, cultural interaction and the broadening of cultural and personal horizons [14]. As translations are border-crossing phenomena, they are embedded within the political, economic and cultural power relations among states and their languages [16, 17]. The production and distribution of translations is therefore governed by largely invisible underlying rules that direct and restrict translation flows worldwide. A closer examination of translations can thus reveal principals of transnational exchange and cultural globalisation. This paper investigates these principals using the example of Dutch bestselling books and the number and kind of translations found among them to determine the Dutch position and role in the global flow of translations.

Historical Outline of Translations from and into Dutch

The Netherlands has historically been – and still is – a book importing and translating nation. Different, partly interdependent factors have promoted this status. First, the Netherlands is a comparatively small country and surrounded by three major powers in the linguistic and cultural fields, namely England, France and Germany. Imports from neighbouring cultures have therefore always been an important part of Dutch cultural identity [18, 19, 38]. Dutch has rather few speakers outside of the Netherlands, so international trading and communication is almost always based on the languages of the respective neighbouring country. Also, the Dutch book market is rather small and not able to maintain a highly diversified book production by itself, so many publishing houses buy translations to complement their domestic division [13]. For these reasons, the Netherlands has always shown a close cultural orientation to dominant international tendencies and more often tends to follow global trends in the cultural field instead of creating them [19].

Generally, book import into the Netherlands is much more frequent than book export to other countries: For roughly every six books that are translated into Dutch, one is translated from Dutch [18]. According to the UNESCO Index translationum, Dutch ranks on the sixth place of translation target languages in global comparison with an absolute number of 99,191 translations between 1979 and 2007 (5.83% of all translations in the Index) [7]. Since the end of World War II and in line with general globalisation tendencies, the number of translations into Dutch has been rising steadily. In 1946, only five percent of all books published in the Netherlands were translations, but this number rose to almost 30% of the national book production in 2000 [19]. In 2019, 38.1% of all books published in the Netherlands were translations [24]. The number of translations, however, is distributed very unevenly between different genres. Regarding fiction, translated books even outweigh the domestic production in the Netherlands, as they account for 54.8% (1,890 titles) of all books published in that genre in 2019 [19, 24]. Translated non-fiction and children’s books, on the other hand, are much less frequent (1,140 titles/25.6% and 950 titles/46.1% respectively) [24].

As shown in Table 1, English-language books dominated as a source language for translations in 2012 and almost made up two thirds of the overall amount of translations (63.1%). With French (15.0%) and German (11.1%), all closely neighbouring languages can be found in the top three, while other languages each only account for less than three percent of the translations book market [37, see also 19].

The Relationship of Languages

To explain asymmetries in the number of translations from and into different languages just mentioned, Wallerstein’s “Modern World System” theory[39] has been applied to the relationship of languages [9, 10, 19,20,21,22]. Wallerstein claims that global power relations can be described in terms of a hierarchical core/semi-periphery/periphery model, the core being most powerful and dominant, while the periphery is largely dependent on the core/semi-periphery [39]. The position a language occupies in this so-called World Language System [e.g. 9, 10, 18] is a determining factor for its translation activities. Centrality corresponds with an export-orientation and few translations into the central language itself, while peripheral countries/languages import much more than they export [20, 30]. What emerges is a system of unequal and sometimes “utterly imbalanced” [1] exchanges between different countries and languages that shapes cultural interaction worldwide. The more central a country is in the World Language System, the more likely it is to act as a cultural role model or trendsetter for other countries that have a more peripheral position [20]. For that reason, there are much more translations from English than translations into English, while an inverse relationship can be observed for “smaller” and more peripheral languages such as Dutch [13]. Peripheral languages usually have a more awaiting and observing position and follow the appealing models of central languages [19].

When applied to languages, it is immediately apparent that “English is by far the most central language in the international translation system”[20], since English is, according to the Index translationum, the source or target language of 75.12% of all translations worldwide [1]. Other languages with a central role, even though to a much lesser extent, are French and German [20]. The languages that are usually considered semi-peripheral include Russian, Spanish, Italian and Swedish, as they have a share of 1–3% of the total number of translated books [16, 20]. Languages with a share of less than one percent are described as being in a peripheral position. It is already evident from this classification that the number of speakers a language has is sometimes, but not always, decisive for the degree of centrality attributed to it, since Chinese, Arabic or Portuguese are considered peripheral in this model [17]. Instead, historical developments (such as colonisation), geographic location and political power play a more important role [9, 16, 22]. Consequently, the model is very open to change, as political power relations and historical events can change the relationship of countries, languages and cultures with each other. The constellation is thus dynamic, not static, and with cultural reorientations, the position a language occupies can change (e.g. the loss of importance of Russian after the end of the Cold War) [19, 21].

Another important consequence of the world system model of languages is that translations usually flow from central to peripheral languages and (less often) vice versa, but only seldom among peripheral languages. Therefore, central languages often are a “linguistic bridge for translation”[14] and function as vehicular or transfer languages [20, 41]. If a book is translated from a peripheral language into a central language, e.g. English, other publishers will often follow these developments closely because being translated into English usually increases a book’s chances to be economically successful [6, 20]. If these books are then in turn translated into another peripheral language from the English version (usually because there are no translators available between the two “small” languages), this is called a retranslation. Interestingly, books that are translated from one peripheral language to another are usually much less successful and not as well received by the critics or the public than books that have been (re-)translated from a core language [20]. This again demonstrates the exemplary function of core languages and the dependency of peripheral languages. The phenomenon of retranslations, once the usual way to translate English books via French into Dutch, has become much less common in the twenty-first centuries, however, in some cases, it still exists [15, 20].

Translation, Cultural Globalisation and Diversity

Translating is a key process for the mediation between different cultures [3]. Translations can be used for varying purposes and can have widely varying effects [14], depending on power structures and underlying goals of the participants. The steady increase of global translation flows over the last decades has generally been interpreted as a sign of ever deeper cultural globalisation. Since it is logical to expect central languages which exert “economic and political influence over other countries to exert a cultural influence as well” [2], various theoretical models of cultural globalisation have been discussed in the past to describe these power relations.

With regard to the existing imbalances in translation traffic and because of the profound impact of translations, some comparisons have even been drawn with colonial history. The cultural imperialism paradigm, for instance, claims that the translation system serves “the geopolitical, economic and cultural interests of wealthy states” [27], especially the United States. Therefore, the phenomenon has also been called “Anglo-American cultural colonization” [22] or “Americanization” [26, 27]. This approach sees translations as imperialistic instruments which are being used as a means to extend and reinforce unequal power relations. However, this view is hardly represented in the debate on translation ratios any more [25]. Not every transnational media relationship is reducible to Americanization, as globalisation also stimulates local cultural industries and increases cultural exchange (especially translations) [8, 29] also source [26]. While it is undeniable that a kind of “global media system” has emerged in recent decades, the very fact that native languages continue to be the preferred language for reading shows that the situation is much more complex [3, 4, 29]. Nowadays, aspects other than political ones are seen as decisive for international relations, especially economic ones.

The commercialisation that has accompanied globalisation has had profound consequences for cultural industries in general and the book sector in particular. Due to the liberalisation of book markets, the increasing agglomeration of publishing houses and shifts in society, national and international markets have been thoroughly reshaped [e.g. 16, 35]. These developments have contributed to the emergence of a global book market that is increasingly characterised by a binary division caused by two different commercial rationales: At the commercial large-scale pole of book production, books “appear primarily as commercial products that must obey the law of profitability” [16]. As a result of commercial constraints and strong international homogenisation and concentration tendencies, linguistic diversity is rather low at the commercial pole [31]. This commercialisation of book markets gave rise to a dominant position of economically powerful book markets with a large book supply (e.g. in the UK and US). However, cultural diversity tends to increase strongly when moving to the upmarket pole of the market [6, 29]. Here, a wide range of (peripheral) texts and cultural experiences is available because publishers’ decisions are rather based on intellectual and aesthetic than on commercial criteria [6, 30]. In the upmarket segment, cultural diversity is often used “as a strategy for fighting the growth of commercial products, mostly translated from English” [29].

In how far the flow of translations in a country is influenced by other cultures obviously depends on the respective culture and language spoken in each country. Therefore, this survey analyses the Dutch position in the World language system and foreign influences on the Dutch book market using the example of translations on the Dutch CPNB Bestseller List.

Data and Methodology

In order to determine the position of Dutch in the world language system, the CPNB Top 100 archief has been used as a database [33]. The Top 100 bestseller list, published in every year since the generation of the first list in 1997, comprises the 100 bestselling books in the Netherlands in the respective year. The list is compiled on the basis of retailer sales data collected by the research agency GfK on behalf of the Dutch Stichting Marktonderzoek Boekenvak [34]. These sales data include brick and mortar book store sales, online stores, entertainment specialists and mass merchandise sales. As the data only represent around nine tenths of the Dutch book sales, the remaining 10% are estimated by means of a calculation model. The list includes publicly available Dutch and Flemish books with a minimum price of 3.50€ [34].

For the purpose of this analysis, only the first 50 entries in each list from 1997 to 2019 were considered. To retrieve information about the author, genre and original language of a book (i.e. to ascertain whether a book is a translation into Dutch or not), the catalogue of the Dutch National Library was used, which contains detailed information about every book [23]. As books that are originally written in Dutch or Flemish are not the main point of interest, they have been left out of the analysis. All books in translation among the first 50 entries on the bestseller list, on the other hand, were collated and statistically analysed according to their original language, author and genre.

Results

Of the 1150 titles examined in the Top 50 lists in the observation period of 23 years, 530 are translations (46.1%). The following two sections present and analyse this translation share of the annual CPNB lists. The first part considers the original language of translations with regard to language prevalence, diversity and retranslations. Second, the nationality of the most successful authors and the genre distribution on the lists will be discussed.

Language

The most striking finding is the remarkable dominance of English as a source language for translations. More than two thirds of all translations into Dutch that made it into the Top 50 are from English (388 out of 530, 73.2%).

Of these English translation, more than half (201) are from books originally written in American English (see Fig. 1). British English ranks second with 159 translations; other Anglophone countries (Ireland, New Zealand, Australia and Canada) together make up 28 translations. Swedish places a distant second with 44 translations in 23 years. All other languages lag far behind English, namely Spanish (25), German (15), French (11), Italian (11), Danish (10) and Norwegian (9). Seven further languages also appear in the Top 50 (Korean, Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, Hebrew, Icelandic, Hungarian), but only sporadically. As can be seen from Fig. 2, the number of original languages other than Dutch varies from year to year with an average of 5.04 translation languages each year.

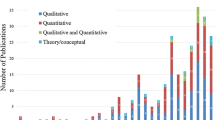

The absolute number of translation also varies each year, being lowest in 1997 with 12 translations among the first 50 books on the bestseller list and highest in 2018 with 30 translations (see Fig. 3 below). The number of translations in the Top 50 lists rises continually from 1997 to 2002, slightly decreases until 2007 and starts to increase again from 2008 onwards. Between 2010 and 2019, the number of translations remains largely steady with two outliers in 2015 and 2016. The figure again clearly displays the dominance of English (in blue hues) compared with the small proportions of other languages. English is the only language that appears on the list in every single year between 1997 and 2019, while Swedish and Spanish appear in 18, German in 13 and French in only 9 out of 23 years. The data show a clear correlation between the absolute number of translations and the number of translations from English. When the total number of translations rises, this rise is usually caused by books from Anglophone countries. Only between 2009 and 2014 the relationship is a bit less close, mainly caused by popular Swedish and Danish books in that period.

As far as the occurrence of certain translation source languages is concerned, the analysis of the bestseller list shows exactly the language ratios one would expect according to the World Language System. 414 out of 530 translations (78.1%) are from the central languages English, German and French. From semi-peripheral languages (here: Italian, Spanish and Swedish) 80 translations appear on the bestseller list (15.1%), from peripheral languages only 36 (6.8%). Even though these relationships are certainly influenced by the Netherlands’ close neighbourly relations with Germany, Wallonia/France and the United Kingdom, it is clear that peripheral languages play a much smaller role than central ones.

As can be seen from Table 2, retranslations are, as expected, a minor phenomenon in the CPNB Top 50. Out of the 26 different titles that were translated from peripheral languages in the sample, five (19.23%) were not translated directly from the original language. In all cases in which retranslations did appear on the lists, the books were translated via the intermediary language English. Also, it is clearly evident from the table that even within the group of peripheral languages, there seems to be a distinction between more and less peripheral languages (at least from a Dutch point of view), because books from Hebrew, Korean, Chinese and Japanese have been retranslated, while other (and mostly European) peripheral languages such as Hungarian, Icelandic or Danish have been translated directly from the original.

Authors and Genres

For the analysis, not only the number of translations, but also the respective authors and their nationality have been considered (Table 3 below). The list consists of all authors with five or more listings in the Top 50 lists 1997–2019. Here again, the dominance of English is conspicuous. Among the first ten most successful authors in the sample, only one (Isabel Allende) is not either from the US (5 authors) or the UK (4). Among the remaining 18 authors on the list, the diversity of represented origin countries is much greater, with eight author nationalities. It would be wrong, though, to interpret this diversity of nationalities as a diversity of languages, because one the one hand, eleven of the 18 authors have written their books in English or their work has been translated from English (Yuval Noah Harari). On the other hand, this statistic shows that most listings of non-English translations into Dutch can be traced back to a handful of (mostly Swedish) authors that had real success in the Netherlands. Hence, the comparatively high number of Swedish translations into Dutch (Fig. 1) does not really represent a diverse range of Swedish books, but the isolated success of few internationally acclaimed bestseller authors, a phenomenon that has also been observed elsewhere (e.g. [5, 40, 41]).

In terms of genre, the data examined reveal that fiction titles make up the vast majority of translations represented on the bestseller lists (Fig. 4). On average, more than four out of five translations on the lists are fiction books (82.1%), while non-fiction and children’s books only account for 15.5% and 2.4% respectively.

In general it can be concluded that a few languages (exclusively European languages, namely English, Swedish, German, Spanish and French) are the dominant source languages for translations into Dutch that make it onto the bestseller list. Comparatively high numbers for peripheral languages such as Hebrew (five listings in three consecutive years) are usually caused by a single successful author and do not really indicate diversity, especially when taking into consideration that the books were translated via the English edition.

Discussion and Conclusions

The World Language System Theory is not a new approach to explain the imbalances in global publishing. It has already been widely discussed in translational and cultural studies, which makes it all the more surprising that few surveys so far have evaluated the theoretical assumptions on the basis of actual publishing data. This analysis used data from Dutch bestseller lists to assess the validity of the claims made by World Language System Theory.

According to the data surveyed here, Dutch can be classified as a peripheral language. This is evident from the high number of translations (46.1%) that find their way onto the Dutch bestseller list every year. The percentage of translations on the lists is even higher than the share of translations in the overall book market (38.1%, see above). This result is probably due to the high proportion of fiction books on the bestseller lists, among which the share of translations is higher than the book market average (see also [12, 19]).

The results presented above also clearly indicate that the presumptions resulting from the theory are accurate: The percentage of translations of a language on the Dutch bestseller list is roughly proportional to the centrality of that language in the World Language System. English, as the most central language, accounts for the largest number of translations, followed by other central and semi-peripheral languages such as Swedish, Spanish, German or French. Peripheral languages, on the other hand, only constitute a minute fragment of all published translations in the analysis.

Additionally, the results suggest that there is a hierarchy of Anglophone nations even within the central language English. While American English is the undisputed frontrunner, followed by British English, other varieties are not represented regularly on the Dutch bestseller list. Despite English books being written in many Anglophone countries around the globe, most books that are translated from English are originally published in either the US or the UK [17]. The results confirm a pattern observed by Driscoll and Rehberg Sedo: Books from other varieties of English in most cases “take longer to travel transnationally, often needing to have their journey facilitated by United States or United Kingdom mediators”[11]. This again underlines the dominance of America as a global cultural centre towards which other countries align themselves, e.g. with language editing [11].

The striking dominance of English is not only expressed in the 72.5% translation share, but also in the high number of bestselling authors (with 20 out of 28 authors appearing more than five times from 1997–2019 writing in English, see Table 3). The dominance of English in the Dutch book market – at least at the pole of large-scale production – means by implication that these translations compete not only among each other, but also with books in the native language [19]. Heilbron claims that “[a]s far as the Netherlands is concerned, the enormous growth of translations from English has not diminished the translations from other languages; it has essentially diminished the role of indigenous books”[20]. Even though the increase in translations from 1997 to 2019 is by no means a linear process which is subject to many more factors apart from international power relations, it seems as if there was a general trend towards more globalisation and more translations. The near-exclusive orientations towards English literature is in line with general globalisation developments all over Europe [e.g. 41], but also demonstrates the dynamic changeability of the World Language System, since the Netherlands was much more oriented towards Germany and France just fifty years ago [10].

Further evidence for the claims made by De Swaan and Heilbron about transnational translational relations is provided by the retranslations found in the CPNB list. Even though the share is comparatively small (19.23%, see Table 2), retranslations via intermediary (central) languages still exist. They are used for languages that are very rare to be translated into Dutch on the one hand and rather far away from the Netherlands in a geographical and linguistic sense on the other land. It can be assumed that these books have only been published in Dutch at all because they were great commercial successes in English or on Anglophone book markets before – otherwise they would likely not have been “discovered” by the Dutch publishing industry.

The bestseller list obviously only gives a very limited insight into the “upper end” of the Dutch book market, however, and is by no means representative as far as language proportions are concerned. Even though the CPNB Top 100 list is one of the rare cases where bestseller lists do come with exact sales data, it might still underestimate the success of English books on the Dutch book market. In most cases where bestseller lists are used as a data basis, the problem arises that the lists are not an objective reflection of actual sales due to weightings, special selection rules or opaque data collection procedures [see e.g. 28, 38, 41]. Although the CPNB list is rather objective (only 10% of sales are estimated and there is no weighting or selection by genre), only Dutch-language books appear on the list. Yet, as Trentacosti and Pilcher report, the Dutch increasingly read books in the original English, mainly due to the on average high level of English proficiency [36]. The turnover share of foreign-language books of total paper book sales in the Netherlands has been steadily rising and doubled from 7% in 2012 to 14% in 2020 [25]. Even though German- and French-language books sold relatively well, too, the majority of books sold in a foreign language are in English [32]. The impact of originally English books might thus be even higher than already indicated by the bestseller lists just analysed.

The bestseller list analysed here can, as indicated, only give an overview about the cultural diversity of the large-scale production. In this respect, the lists are rather inconclusive. On average, 5.04 languages are represented in the Top 50 each year, which is a surprising result considering the assumed dominance of the English language in general and the US in particular. However, English is the only language that is present every year, some languages only show up once or twice and the majority of titles from non-English authors are internationally acclaimed bestsellers. Additionally, the five languages that do appear regularly in the list (English, Swedish, Spanish, German, French and Italian) are all central or at least semi-peripheral languages. Hence, they show again that a certain amount of diversity is present in the Dutch book market, but that it is nevertheless ruled by underlying linguistic and commercial constraints. For further research, it would be interesting to compare the Dutch bestseller list to similar lists from other peripheral countries to look for similarities, differences or further proof for the findings stated above.

Taken together, the analysis of the bestseller lists shows a contrast characteristic of Dutch cultural industries: As a politically, culturally and linguistically “small” nation, the Netherlands is constantly searching for an “acceptable balance between the great international examples and a modest own contribution” [19] (my translation). The translations at the large-scale production pole of the book market analysed here are clearly dominated by English – in some years to an extent that English does not only dominate translations, but the whole list. Dutch can definitely be identified as a peripheral language in the world system of languages. With regard to cultural diversity on the list, ambiguous results have been found. While English is not the only language represented in the Top 50, most other languages are either similarly in central or semi-peripheral positions. A high number of translations also diminishes the diversity of Dutch language books represented in the list. Overall, the findings suggest that bestsellers in the Netherlands are increasingly globalised phenomena and reveal a “fundamental asymmetry of exchanges among languages” [7].

References

Bellos D. Is that a fish in your ear?: The amazing adventure of translation. London: Penguin Books; 2012.

Beltran S, Ramiro L. Communication and cultural domination: USA-Latin American case. Media Asia. 1978;5(4):183–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/01296612.1978.11725945.

E Bielsa. Globalisation as translation: An approximation to the key but invisible role of translation in globalisation University of Warwick Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation; 2005.

Bielsa E. Beyond hybridity and authenticity: Translation and the cosmopolitan turn in the social sciences. Synthesis: an Anglophone Journal of Comparative Literary Studies 2012;4:11–21. https://doi.org/10.12681/syn.17281

Böker E. Skandinavische Bestseller auf dem deutschen Buchmarkt. Analyse des gegenwärtigen Literaturbooms. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann; 2018.

Bourdieu P. The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1993.

Brisset A, Godbout M. Globalization, translation, and cultural diversity. Translation and Interpreting Studies. The Journal of the American Translation and Interpreting Studies Association 2017;12(2):253–277.

Cronin M. Translation and globalization. Abingdon: Routledge; 2003.

De Swaan A. Words of the world. Cambridge, UK, Polity; 2001.

De Swaan A. Dutch in the world language system. CLINA An Interdisciplinary Journal of Translation, Interpreting and Intercultural Communication 2016;2(2):11–14. https://doi.org/10.14201/clina2016221114

Driscoll B, Rehberg SD. The transnational reception of bestselling books between Canada and Australia. Global Media Commun. 2020;16(2):243–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742766520921910.

Franssen T. Diversity in the large-scale pole of literary production: an analysis of publisher’s lists and the Dutch literary space, 2000–2009. Cult Sociol. 2015;9(3):382–4.

Ginsburgh V, Weber S, Weyers S. The economics of literary translation: Some theory and evidence. Poetics. 2011;39(3):228–32.

Grossman E. Why translation matters. New Haven/London: Yale University Press; 2010.

Hacohen R. Literary transfer between peripheral languages: a production of culture perspective. Meta. 2014;59(2):297–303. https://doi.org/10.7202/1027477ar.

Heilbron J, Sapiro G. Outline for a sociology of translation: Current issues and future prospects. In: Wolf M, Fukari A, editors. Constructing a sociology of translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2007. p. 93–101.

Heilbron J, Sapiro G. Translation: Economic and sociological perspectives. In: Ginsburg V, Weber S, editors. The Palgrave handbook of economics and language. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2016. p. 373–4.

Heilbron J. Mondialisering en transnationaal verkeer. Amsterdams sociologisch tijdschrift. 1995;22(1):162–71.

Heilbron J. Nederlandse vertalingen wereldwijd. Kleine landen en culturele mondialisering. Waarin een klein land. Nederlandse cultuur in internationaal verband; 1995. p. 206–253.

Heilbron J. Towards a sociology of translation: Book translations as a cultural world-system. Eur J Soc Theory. 1999;2(4):429–44.

Heilbron J. Translation as a cultural world system. Perspectives. 2000;8(1):9–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2000.9961369.

Heilbron J. Responding to globalization: the development of book translations in France and the Netherlands. In: Shlesinger M, Simeoni D, editors. Pym A. John Benjamins: Beyond descriptive translation studies. Investigations in homage to Gideon Toury. Amsterdam; 2008. p. 187–97.

Koninklijke Bibliotheek Nationale Bibliotheek van Nederland. KB-Catalogus. [online]. Available at: https://www.kb.nl and https://opc-kb.oclc.org/.

KVB. Boekwerkmonitor Factsheet markt, makers, uitgevers, boekverkopers, lezers. 2020, [online]. Available at: https://kvbboekwerk.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Factsheet-definitief.pdf.

KVB. Boekwerkmonitor Kerncijfers boekenmarkt. 2021, [online] Available at: https://kvbboekwerk.nl/monitor/markt/kerncijfers-boekenmarkt-2020.

Legrain P. Cultural globalization is not Americanization. Chron High Educ. 2003;49(35):7–7.

Mirrlees T. Global entertainment media: Between cultural imperialism and cultural globalization. Abingdon: Routledge; 2013.

O’Hagan J. European statistics on participation in the arts and their international comparability. In: Ateca-Amestoy VM, Ginsburgh V, Mazza I, John OH, Prieto-Rodriguez J, editors. Enhancing participation in the arts in the EU. Springer International: Cham; 2017.

Sapiro G. Globalization and cultural diversity in the book market: the case of literary translations in the US and in France. Poetics. 2010;38(4):419–39.

Sapiro G. Translation and symbolic capital in the era of globalization: French literature in the United States. Cult Sociol. 2015;9(3):320–46.

Sapiro G. How do literary works cross borders (or not)?: A sociological approach to world literature. J World Lit. 2016;1:81–96.

Statista.com. Book Market in the Netherlands. Statista Dossier. 2020, [online]. Available at: https://www.statista.com/study/39372/book-market-in-the-netherlands-statista-dossier/.

Stichting Collectieve Propaganda van het Nederlandse Boek (CPNB). CPNB Top 100 archief 1997–2019. [online]. Available at: https://www.cpnb.nl/campagnes/cpnb-top-100-2019/uitgaven.

Stichting Collectieve Propaganda van het Nederlandse Boek (CPNB). CPNB Top 100 bestverkochte boeken 2019. January 2020 [online]. Available at: https://www.cpnb.nl/sites/default/files/cpnb_files/Top1002019/CPNB%20Top%20100%20bestverkochte%20boeken%202019_HR_0.pdf.

Sutherland J. Bestsellers: A very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Trentacosti G, Pilcher N. Dealing with the competition of English-language export editions: Voices from the Dutch trade book market. Publ Res Quarter. 2021;37(2):278–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09798-6.

Van Baelen C. 1+1 = zelden 2. Over grensverkeer in de Vlaams-Nederlandse literaire boekenmarkt. Den Haag: Nederlandse Taalunie; 2013 [online]. Available at: https://literairvertalen.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/11zelden2.pdf.

Van Boven E. Bestsellers in Nederland 1900–2015. Antwerpen/Apeldoorn: Garant; 2015.

Wallerstein I. The modern world system. New York/London: Academic Press; 1974.

Westlund B. Domestic authors claim half of the bestseller listings. Svensk Bokhandel. 2005, [online]. Available at: https://www.svb.se/nyheter/domestic-authors-claim-half-bestseller-listings.

Wischenbart R, Kovač M, Fleischhacker MA. Diversity Report 2020. Trends in literary translation in Europe. 2021, [online] Verein für kulturelle Transfers–CulturalTransfers.org. Available at: http://bit.ly/DivRep2020.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

CPNB Stichting Collectieve Propaganda van het Nederlandse boek (Foundation for Collective Propaganda of Dutch Books)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Valentin, L. Language, Power and Success: Bestselling Translations in the Dutch CPNB Top 100 archief. Pub Res Q 37, 439–452 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09823-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09823-8