Abstract

Purpose

To analyze the 3-month life expectancy rate in pancreatic cancer (PC) patients treated within prospective trials from the German AIO study group.

Patients and methods

A pooled analysis was conducted for patients with advanced PC that were treated within five phase II/III studies conducted between 1997 and 2017 (Gem/Cis, Ro96, RC57, ACCEPT, RASH). The primary goal for the current report was to identify the actual 3-month survival rate, a standard inclusion criterion in oncology trials.

Results

Overall, 912 patients were included, 83% had metastatic and 17% locally advanced PC; the estimated median overall survival (OS) was 7.1 months. Twenty-one percent of the participants survived < 3 months, with a range from 26% in RC57 to 15% in RASH. Significant predictors for not reaching 3-month OS were > 1 previous treatment line (p < 0.001) and performance status (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Despite the definition of a life expectancy of > 3 months as a standard inclusion criterion in clinical trials for advanced PC, a significant proportion of study patients does not survive > 3 months.

Trial registration numbers

NCT00440167 (AIO-PK0104), NCT01729481 (RASH), NCT01728818 (ACCEPT).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer still remains one of the most lethal malignancies and is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer-related death by 2030 [1]. Numerous clinical trials have been conducted since the introduction of gemcitabine in 1997, with most of them being negative for the primary endpoint OS [1]. Two positive phase III studies (PRODIGE/ACCORD-11/0402 and MPACT) have implemented our current standard regimens for metastatic pancreatic cancer, FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel [2, 3]. Our group has conducted five prospective, multicenter phase II/III studies in advanced pancreatic cancer since 1997, all of them within the national AIO (“Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie”) study group of the German Cancer Society. All five trials (Gem/Cis, Ro96, RC57, ACCEPT, RASH) have been published in peer-reviewed international journals: details on study design and clinical results from each study can be found in these original reports [4,5,6,7,8]. Additionally, the major trial characteristics of the current pooled analysis from these first-line studies are summarized in Table 1.

Nearly all clinical trials in gastrointestinal oncology (and in oncology overall) have introduced predefined inclusion criteria regarding life expectancy: in pancreatic cancer usually a life expectancy of at least 3 months is required to enter a patient in a prospective trial investigating systemic therapy. The purpose of this approach usually is to exclude patients with a very poor prognosis (e.g., determined either by host factors or tumor biology), often associated with a risk of early drop-out, and thus allowing a profound analysis of relevant clinical endpoints like objective treatment response and toxicity in the study cohort [9]. However, this specific inclusion criterion of a life expectancy of at least 3 months is of course based on the subjective judgement of the local investigator.

We, thus, aimed to analyze the 3-month survival rate und clinical predictors of this time-to-event endpoint in a large cohort of pancreatic cancer patients who all were treated within trial protocols of the AIO study group conducted during the last two decades in a German multicenter setting.

Materials and methods

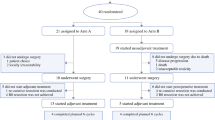

Five prospective, multicenter AIO trials led by our Munich group were included in this pooled analysis: Gem/Cis, Ro96, RC57 (AIO-PK0104), ACCEPT, RASH [4,5,6,7,8]. The overall recruiting period was December 1997–January 2017. While the studies Gem/Cis, Ro96 and RC57 included both locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer, the two latest trials ACCEPT and RASH only recruited patients with metastatic disease. Three trials had a phase II design, 2 studies were phase III protocols (for details see Table 1). In all protocols, a life expectancy of at least 3 months (based on the assessment of the treating physician) had been requested as a trial inclusion criterion.

Individual patient data from 912 patients were included in a combined database, time-to-event endpoints were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method, differences between groups were compared using the log-rank test. Chi-squared nonparametric statistics were employed to analyze categorical data and determine if any significant associations or differences existed among the variables. For statistical analysis, the SPSS software package, version 29, was used.

Results

In the 912 patients included in this pooled analysis, median age was 63 years (range 24–89 years), 59% of the patients were male and 83% had metastatic disease at study entry. Thirty-two percent of the patients analyzed had an ECOG performance status of 0, 54% an ECOG of 1 and 10% an ECOG of 2. The median OS was estimated with 7.1 months (95% CI 6.5–7.6 months) in the entire population of study patients and is 9.0 months (95% CI 8.4–9.6 months) for all patients with a survival ≥ 3 months. 48% of patients included in the AIO trials received any kind of second-line therapy after failure of first-line study treatment.

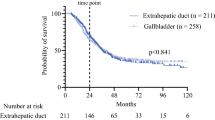

The detailed results of the 3-month survival analysis are summarized in Table 2: in the overall dataset, 21% of the patients died before month 3 after trial inclusion, with the numerically highest (26%) rate in the phase III RC57 (AIO-PK0104) study and the lowest (15%) in the RASH study. Further subgroup analysis showed a significant correlation of the 3-month survival rate with the use of subsequent treatment after failure of first-line therapy (p < 0.001) and ECOG performance status (p < 0.001). No association with 3-month survival was found for gender (p = 0.972), age (p = 0.227), and primary tumor localization in the pancreas (p = 0.058).

Discussion

Conducting clinical trials in advanced pancreatic cancer remains a challenge, with a high proportion of negative studies and a highly vulnerable, poor-prognosis patient population. The definition of trial inclusion criteria is essential for the trial population and in the end of course also for the efficacy and safety results of a study. A good example in this context is the PRODIGE/ACCORD-11/0402 trial that investigated the use of the intensive 4-drug regimen FOLFIRINOX in metastatic pancreatic cancer: this study had restrictive inclusion criteria on host factors like performance status, organ function (e.g., liver) and co-morbidities [2]. Despite these rather “objective” inclusion criteria, many (if not nearly all) trials investigating systemic therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer during the last two decades also included a life expectancy of at least 3 months as a criterion for study entry: a fact that also is true for all our 5 AIO studies analyzed here [4,5,6,7,8]. However, as the current pooled analysis shows, a significant proportion of patients (21%) treated in these five protocols did in fact not survive more than 3 months after study entry. The 3-month survival rate was the highest (86%) in the RASH study (Table 2), which of interest used the same inclusion criteria as the PRODIGE/ACCORD-11/0402 study, as it also investigated the use of FOLFIRINOX (in patients not developing skin rash after a 4-week lead-line treatment with gemcitabine + erlotinib) [7].

One might conclude from these data that a strict selection of patients based on organ function, performance status, and co-morbidities better selects poor-prognosis patients than the sole assessment of expected prognosis by the treating oncologist. In a cross-trial comparison approach estimated from the published Kaplan–Meier curves from PRODIGE/ACCORD-11/0402 and MPACT, an early death rate of about 10–15% occurred during the first 3 months after randomization in these pivotal phase III trials as well [2, 3]. A proportion of approximately 20% of patients not alive 3 months after study entry was also reported in the international phase III NAPOLI-3 trial, that was presented recently at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and compared a novel regimen called NALIRIFOX with standard gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel [10].

When reflecting on these—at least in our opinion—clinically relevant data, one must keep in mind that a transfer of data from controlled clinical trials in advanced pancreatic cancer to a patient population that we see in the clinical routine may have several limitations. In the meanwhile it is quite evident that a significant proportion of European patients with advanced pancreatic cancer may not receive tumor-specific treatment at all and that survival in unselected, population-based registries often is reported to be very poor (in the range of 2–3 months) for patients newly diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer [11,12,13,14,15]. Thus, the oncological community should make every effort to increase the proportion of patients with pancreatic cancer who receive effective tumor-specific treatment, enhance the recruitment for clinical trials and select patients for trials not only under aspects of drug approval but also for post-approval generalizability of the data real-word patients [16].

In the current literature, only limited studies and articles address the question whether the 3-month life expectancy is a valid inclusion criterion for clinical trials, especially in the phase II and phase III setting [9]. Based on an own literature search, the authors did not find publications on this topic for pancreatic cancer up to now; however, some evidence is available from other gastrointestinal malignancies like colorectal cancer [17, 18].

In conclusion, the authors believe that—also based on our data reported here—the common standard inclusion criterion of “3-month life expectancy” for clinical trials in pancreatic cancer should be discussed very critically and a removal of this criterion on the list of trial participation criteria seem reasonable for future studies. A selection of patients should instead be performed using relevant host factors (like organ function, performance status, and co-morbidities) and ideally also novel parameters that reflect tumor biology—while this may, on the other hand, may limit the generalizability of trial results.

Data availability

Available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Park W, Chawla A, O’Reilly EM. Pancreatic cancer: a review. JAMA. 2021;326(9):851–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.13027.

Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–25. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011923.

Goldstein D, El-Maraghi RH, Hammel P, Heinemann V, Kunzmann V, Sastre J, et al. nab-Paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer: long-term survival from a phase III trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(2): dju413. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju413.

Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schönekäs H, Rost A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3946–52. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490.

Boeck S, Hoehler T, Seipelt G, Mahlberg R, Wein A, Hochhaus A, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CapOx) versus capecitabine plus gemcitabine (CapGem) versus gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin (mGemOx): final results of a multicenter randomized phase II trial in advanced pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(2):340–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm467.

Heinemann V, Vehling-Kaiser U, Waldschmidt D, Kettner E, Märten A, Winkelmann C, et al. Gemcitabine plus erlotinib followed by capecitabine versus capecitabine plus erlotinib followed by gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: final results of a randomised phase 3 trial of the “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie” (AIO-PK0104). Gut. 2013;62(5):751–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302759.

Haas M, Siveke JT, Schenk M, Lerch MM, Caca K, Freiberg-Richter J, et al. Efficacy of gemcitabine plus erlotinib in rash-positive patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer selected according to eligibility for FOLFIRINOX: A prospective phase II study of the “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie.” Eur J Cancer. 2018;94:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.02.008.

Haas M, Waldschmidt DT, Stahl M, Reinacher-Schick A, Freiberg-Richter J, Fischer von Weikersthal L, et al. Afatinib plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone as first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer: the randomised, open-label phase II ACCEPT study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie with an integrated analysis of the “burden of therapy” method. Eur J Cancer. 2021;146:95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.12.029.

Penel N, Clisant S, Lefebvre JL, Adenis A. “Sufficient life expectancy”: an amazing inclusion criterion in cancer phase II-III trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26): e105. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1810.

O’Reilly EM, Melisi D, Macarulla T, Pazo Cid RA, Chandana SR, De La Fouchardiere C, et al. Liposomal irinotecan + 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin + oxaliplatin (NALIRIFOX) versus nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine in treatment-naive patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (mPDAC): 12- and 18-month survival rates from the phase 3 NAPOLI 3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16_suppl):4006. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.4006.

Bjerregaard JK, Mortensen MB, Schønnemann KR, Pfeiffer P. Characteristics, therapy and outcome in an unselected and prospectively registered cohort of pancreatic cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(1):98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.07.017.

Kirkegård J, Bojesen AB, Nielsen MF, Mortensen FV. Trends in pancreatic cancer incidence, characteristics, and outcomes in Denmark 1980–2019: a nationwide cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022;80: 102230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2022.102230.

Bernards N, Haj Mohammad N, Creemers GJ, de Hingh IH, van Laarhoven HW, Lemmens VE. Ten weeks to live: a population-based study on treatment and survival of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer in the south of the Netherlands. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(3):403–10. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2014.953257.

Golan T, Sella T, Margalit O, Amit U, Halpern N, Aderka D, et al. Short- and long-term survival in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, 1993–2013. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(8):1022–7. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2017.0138.

Mackay TM, van Erning FN, van der Geest LGM, de Groot JWB, Haj Mohammad N, Lemmens VE, et al. Association between primary origin (head, body and tail) of metastasised pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and oncologic outcome: a population-based analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2019;106:99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.10.008.

Boeck S, Heinemann V, Werner J. Comment on: “Detection, treatment, and survival of pancreatic cancer recurrence in the Netherlands: a nationwide analysis.” Ann Surg. 2022;276(6):e1123–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005405.

Grellety T, Cousin S, Letinier L, Bosco-Lévy P, Hoppe S, Joly D, et al. PRognostic factor of early death in phase II Trials or the end of “sufficient life expectancy” as an inclusion criterion? (PREDIT model). BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):768. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2819-7.

Pietrantonio F, Miceli R, Rimassa L, Lonardi S, Aprile G, Mennitto A, et al. Estimating 12-week death probability in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: the Colon Life nomogram. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(3):555–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw627.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all patients and their families, nurses, study coordinators and investigators for their active participation in all five multicenter AIO studies that formed the data basis for the current pooled analysis. JTS is supported by the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK).

Previous presentation

This work was presented in part as an oral abstract at the World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), 28 June – 1 July 2023, Barcelona, Spain.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. For the current pooled analysis no specific extramural funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Volker Heinemann, Frank Gieseler, Thomas Hoehler, Julia Mayerle, Detlef Quietzsch, Anke Reinacher-Schick, Michael Schenk, Gernot Seipelt, Jens T. Siveke, Michael Stahl, Ursula Vehling-Kaiser, Dirk T. Waldschmidt, Christoph B. Westphalen, Stefan Boeck, and Michael Haas provided patients and clinical data. Lena Weiss, Volker Heinemann, Laura E. Fischer, Klara Dorman, Danmei Zhang, Michael von Bergwelt-Baildon, Stefan Boeck, and Michael Haas performed the data analysis and interpretation. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Lena Weiss, Stefan Boeck, and Michael Haas, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Lena Weiss has received honoraria for scientific presentations from Roche and Servier and travel accommodation expenses from Amgen. Volker Heinemann received honoraria for talks and advisory board role for Merck, Amgen, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre, AstraZeneca, BMS; MSD, Novartis, Terumo, Oncosil, NORDIC, Seagen, GSK. Research funding from Merck, Amgen, Roche, Sanofi, Boehringer-Ingelheim, SIRTEX, Servier. Anke Reinacher-Schick received honoraria from Amgen, Roche, Merck Serono, BMS, MSD, MCI Group, Astra Zeneca, for advisory and consultancy Amgen, Roche, Merck Serono, BMS, MSD, Astra Zeneca, Pierre Fabre, Research grant/Funding Roche, Celgene, Ipsen, Amgen, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Atra Zeneca, Lilly, Servier, AIO Studien gGmbH, Rafael Pharmaceutics, Erytech Pharma, BioNTech, Travel expenses Roche, Amgen, Pierre Fabre. Jens T. Siveke receives honoraria as consultant or for continuing medical education presentations from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Immunocore, MSD Sharp Dohme, Novartis, Roche/Genentech, and Servier. His institution receives research funding from Abalos Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisbach Bio, and Roche/Genentech; he holds ownership and serves on the Board of Directors of Pharma15, all outside the submitted work. Michael Stahl received honoraria from Lilly. Klara Dorman has received travel support from Servier, GSK, and BMS, as well as honoraria from AstraZeneca. Danmei Zhang received honoraria from Astra Zeneca. Stefan Boeck had a consulting and advisory role for Celgene, Servier, Incyte, Fresenius, Janssen-Cilag, AstraZeneca, MSD, and BMS, and received honoraria for scientific presentations from Roche, Celgene, Servier, and MSD. Michael Haas has received travel support from servier and honoraria for scientific presentations from Falk Foundation. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval, informed consent and consent to participate/to publish

All 5 clinical trials reported here were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. All study protocols were reviewed and approved by the lead Ethics Committee of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany and additionally by the Ethics Committees of the participating centers. Written informed consent for trial participation and for publication of trial results was obtained from each patient before any study specific procedure.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weiss, L., Heinemann, V., Fischer, L.E. et al. Three-month life expectancy as inclusion criterion for clinical trials in advanced pancreatic cancer: is it really a valid tool for patient selection?. Clin Transl Oncol 26, 1268–1272 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03323-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03323-1