Abstract

Background

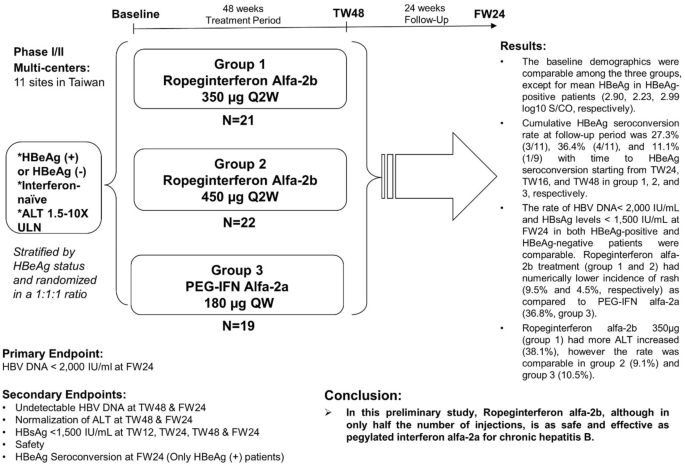

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b is a novel mono-pegylated interferon that has only one major form as opposed to 8–14 isomers of other on-market pegylated interferon, allowing injection every two or more weeks with higher tolerability. It received European Medicines Agency and Taiwan marketing authorization in 2019 and 2020, for treatment of polycythemia vera. This phase I/II study aimed to have preliminary evaluation of safety and efficacy in chronic hepatitis B.

Methods

Thirty-one HBeAg-positive and 31 HBeAg-negative were stratified by HBeAg status and randomized at 1:1:1 ratio to q2w ropeginterferon alfa-2b 350 μg (group 1), q2w 450 μg (group 2) or q1w PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg (group 3). Each patient received 48-week treatment (TW48) and 24-week post-treatment follow-up (FW24).

Results

The baseline demographics were comparable among the three groups, except for mean HBeAg in HBeAg-positive patients (2.90, 2.23, 2.99 log10 S/CO, respectively). Cumulative HBeAg seroconversion rate at follow-up period was 27.3% (3/11), 36.4% (4/11), and 11.1% (1/9) with time to HBeAg seroconversion starting from TW24, TW16, and TW48 in group 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The rate of HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL and HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL at FW24 were comparable in all groups. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b (group 1 & 2) had numerically lower incidence of rash (9.5% and 4.5%) as compared to PEG-IFN alfa-2a (36.8%). Ropeginterferon alfa-2b 350 μg (group 1) had more ALT elevation (38.1%), however the rate was comparable in group 2 (9.1%) and group 3 (10.5%).

Conclusion

In this preliminary study, ropeginterferon alfa-2b, although in only half the number of injections, is as safe and effective as pegylated interferon alfa-2a for chronic hepatitis B.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major public health problem worldwide and affects over 257 million people globally [1]. Pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) alfa and nucleos(t)ide analogues (NUCs) are approved for treatment of chronic HBV infection. PEG-IFN alfa, entecavir and tenofovir are the preferred first-line treatment for chronic HBV infection.

NUCs lead to on-treatment suppression of HBV DNA, regression of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis, reduction of disease progression and hepatocellular carcinoma [2, 3]. However, HBsAg clearance is difficult to achieve by NUCs as HBV is integrated in the host genome and persists in covalently closed circular DNA form in the hepatocyte, even after HBV DNA is not detectable in the serum [4, 5]. NUCs have the advantage as oral form, but their effect on virus elimination or off-treatment permanent suppression is limited.

PEG-IFN alfa therapy leads to higher rates of HBeAg and HBsAg seroconversion than NUCs. HBeAg seroconversion and HBsAg clearance represent an immune control of the chronic HBV infection. PEG-IFN alfa treatment of 48 weeks’ duration yields HBeAg seroconversion rates of 20–31%. These endpoints of sustained off-therapy virological response and HBeAg seroconversion are more desirable than only maintained virological remission under continuous NUCs. Sustained HBeAg and HBsAg negativity up to 37% and 11%, respectively, were observed in HBeAg-positive patients treated with PEG-IFN alfa at a mean follow-up of 3 years. Among those with HBeAg loss at 26 weeks post-treatment, sustained HBeAg and HBsAg negativity were up to 81% and 30% [6]. Although PEG-IFN alfa has the advantages of sustained off-therapy response, premature discontinuation had been reported in up to 20% during chronic hepatitis B treatment [7]. Among the side effects of PEG-IFN, depression and suicidal ideation is the one that correlates with poorer treatment response independent of dose reduction and needs special precaution [8]. Previously, Novartis developed albinterferon dosed every two weeks for treatment of chronic viral hepatitis, aiming to reduce injection frequency and adverse events of weekly PEG-IFN. However, the project had to be discontinued after lung toxicities were noted [9,10,11].

Mono-PEGylated interferon alfa-2b (INN: ropeginterferon alfa-2b; P1101; Besremi™) has been developed by site-specific conjugation of a 40 kDa branched mPEG polymer to an engineered proline-IFN alfa-2b molecule. The generation of pro-IFN alfa-2b, recombinantly expressed in bacteria by engineering an extra proline at the N-terminus of human IFN alfa-2b, and the redesigned PEG moiety allow specific PEGylation to preferentially occur at the N-terminal proline. Thus, ropeginterferon alfa-2b is a novel mono-pegylated IFN alfa-2b with unique structural characteristics that has only one major form as opposed to the 8–14 isomers of other PEGylated IFN alfa products (US Patent No. 8143214. 2012-03-27.) (Counterpart: TW Patent No. I381851. 2013-01-11; JP Patent No. 5613050. 2014-09-12; KR Patent No. 10/15888465. 2016-01-19; AU Patent No. 2008286742. 2014-09-11; CA Patent No. 2696478. 2018-10-09).

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b has longer duration of action, allowing injection every two or more weeks with higher tolerability. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b received European Medicines Agency marketing authorization in 2019 (https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/besremi) and Taiwan marketing authorization in 2020 for the treatment of polycythemia vera. In contrast, weekly PEG-IFN alfa-2a had been studied in PV patients but was eventually given up by hematologists because of intolerance [12, 13] and is not approved for PV. This shows a clear advantage of biweekly ropeginterferon alfa-2b over weekly PEG-IFN alfa-2a in the PV patient population in terms of compliance/tolerance, which potentially can be extended to hepatitis B patients.

In phase I study of ropeginterferon alfa-2b, a total of 48 healthy subjects were enrolled. There were 6 cohorts and each cohort enrolled 6 subjects who received a single dose of ropeginterferon alfa-2b (24, 48, 90, 180, 225, 270 μg) and 2 subjects who received a single dose of PEG-IFN alfa-2a (180 μg). In safety part, majority of reported AEs were mild or moderate in intensity. No clinically meaningful changes were observed in laboratory assessments, physical examinations, vital signs measurements, or ECG results. In pharmacokinetics (PK) results, the geometric mean values of ropeginterferon alfa-2b for Cmax, AUC and AUC0-t showed an increase of 76%, 66%, and 82%, respectively compared to PEG-IFN alfa-2a at the 180 μg dose level. Mean Pharmacodynamics (PD) parameters (Emax, Tmax, and AUC0-t) of ropeginterferon alfa-2b increased with dose for both neopterin and 2, 5- OAS. The PD data showing no statistically significant difference between ropeginterferon alfa-2b and PEG-IFN alfa-2a at the 180 μg dose level. (unpublished data). Furthermore, ropeginterferon alfa-2b dose up to 450 µg was safe and well-tolerated in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 and 2 infection, both studies were completed [14, 15]. In this study, we aimed to have preliminary evaluation of safety and efficacy of ropeginterferon alfa-2b in chronic HBV-infected patients.

Methods

Study population

Adult patients with the following criteria at screening were eligible: positive HBsAg ≧ 6 months; serum ALT levels 1.5–10 times ULN; serum HBV DNA levels > 20,000 IU/mL for HBeAg-positive and > 2000 IU/mL for HBeAg-negative patients; compensated liver disease with total bilirubin < 2 mg/dL, albumin levels ≧ 3.5 g/dL, INR ≦ 1.5; interferon treatment naïve; no other form of chronic liver disease; no significant steatohepatitis on ultrasound or other procedures; negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C and hepatitis D infection; normal fundoscopic examination at screening.

Patients with any of the following criteria at screening were excluded: clinically significant vital sign abnormalities, hemoglobin < 10 g/dL, WBC count < 3000/mm3, absolute neutrophil count < 1500/mm3, platelet count < 90,000/mm3, abnormal serum creatinine, alcohol or substance abuse, poorly controlled psychiatric or systemic disease, coagulation disorders, a depot injection or an implant of any drug within 3 months prior to administration of study medication other than contraception, organ transplant and are taking immunosuppressants, cancers (except those considered cured), history of opportunistic infection, serious localized or systemic infection within 3 months prior to screening, any other clinical conditions that may interfere with study participation or absorption, distribution, metabolism or excretion of the study drug, pregnancy or unwillingness to abstain from contraception. Any systemic antiviral treatment, including nucleos(t)ide analogues for HBV, anti-neoplastic, and immunomodulatory agents should be washed out for at least 1 month or 3 months for those with longer elimination half-lives prior to the first dose of the study drug.

Study design

This was a Phase I/II multicenter, open-label, randomized, active control, dose finding study conducted at 11 medical centers in Taiwan between 2014 and 2017. Total of 62 patients were enrolled, 31 hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients and 31 HBeAg-negative patients were stratified by HBeAg status and randomized at 1:1:1 ratio to ropeginterferon alfa-2b 350 μg q2w (group 1), ropeginterferon alfa-2b 450 μg q2w (group 2) or PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg qw (group 3) (Fig. 1). Every patient received 48-week treatment (i.e. 24 injections per patient in ropeginterferon alfa-2b groups and 48 injections per patient in the PEG-IFN alfa-2a group) and 24 weeks post-treatment follow-up. The study was completed on Sep 2, 2017.

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b was supplied in a sterile, single-use prefilled syringe (500 μg/mL/syringe; PharmaEssentia Corp., Taiwan). PEG-IFN alfa-2a was supplied in a sterile, single-use prefilled syringe (PEGASYS®, 180 μg/0.5 ml/ syringe; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). Ropeginterferon alfa-2b was injected subcutaneously once every 2 weeks, while the active comparator was injected subcutaneously once every week.

Assessment and endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL at 24 weeks of follow-up. Secondary endpoints include the rate of HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL, and ALT normalization (≦ ULN) at the end of 48 weeks treatment and at 24 weeks of follow-up; HBsAg < 1500 IU/mL at 12 weeks, 24 weeks, 48 weeks of treatment, and at 24 weeks of follow-up; HBeAg seroconversion, defined as loss of HBeAg and the development of anti-HBe in HBeAg-positive patients; and safety throughout the study. The analyses of efficacy endpoints were performed in ITT and PP population. The conclusion was based on the results of ITT population.

Serum HBV DNA levels were measured by TaqMan HBV Test (Roche, lower limit of detection, [LOD], < 20 IU/mL). Serum HBsAg levels (LOD < 0.05 IU/mL) and HBeAg levels (LOD: < 1.0 signal/cut-off, S/CO) were measured by Chemiluminescent Microparticle Immunoassay (Abbott ARCHITECT® HBsAg, HBeAg reagent kit). The ALT value was tested at the study site laboratory and the upper limit of normal at each study site ranged from 30 to 41 U/L. The assessment of AE was based on the investigator’s clinical judgment with reference to MedDRA coding and NCI-CTCAE version 4.0.

Statistical analyses

Efficacy analyses were performed using intent-to-treat (ITT) population and per-protocol (PP) population. ITT population included all randomized patients receiving ≥ 1 dose of study drug and ≥ 1 evaluable follow-up evaluation. PP population included all randomized patients receiving at least 80% compliance of study drug, ≥ 1 evaluable follow-up evaluation, and completed the study without major protocol violations. The safety population included all patients receiving ≥ 1 dose of study drug. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 or higher.

Sample size

The sample size of this study was not statistically powered and the analyses were not hypotheses driven but exploratory in nature. We expect to have the preliminary evaluation of safety and efficacy across the treatment groups by 20 patients in each group. The results will be used to plan future hepatitis B trials.

Results

Patient characteristics

In this study, a total of 123 subjects were screened; 61 (49.6%) subjects were not randomized due to failure to fulfill the inclusion and exclusion criteria or withdrawal consent. Of these 61 subjects with screening failure (Supplemental Table 1), 51 subjects did not meet inclusion criteria #2 (ALT elevation or HBV DNA level did not meet). Additional 2, 1 and 2 of them did not meet the inclusion criteria #3, #6 and #7, respectively. Furthermore, 2 subjects were excluded by exclusion criteria #3 and 1 subject was excluded by exclusion criteria #10. The other two subjects withdrew during the screening period.

Sixty-two patients were enrolled to the study (Fig. 1) and were randomized into 3 treatment groups: 21 in group 1, 22 in group 2, and 19 in group 3. The mean age, gender, race, HBeAg status, ALT level were comparable among three groups (Table 1). Baseline HBV DNA level, HBsAg level, and ALT level were comparable in both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients. In HBeAg-positive, patients in group 2 had lower baseline mean HBeAg level, 2.23 log10 S/CO as compared to either group 1 (2.90 log10 S/CO) or group 2 (2.99 log10 S/CO).

Safety

A total of 598 treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported. Among them, 432 TEAEs in 57 patients were reported as related to the study drug (i.e. related TEAEs in Table 2). One (4.8%) SAE in group 1, the patient was hospitalized due to myocardial infarction. No death was reported in this study. Related TEAEs leading to dose discontinuation were comparable among the three groups.

Related TEAEs of ≧10% were shown in Table 2. No depression was reported in this study. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b treatment (group 1 and 2) had numerically lower incidence of rash (9.5% and 4.5%, respectively) as compared to PEG-IFN alfa-2a (36.8%, group 3). The rate of ALT elevation was higher in group 1 (38.1%), but not in group 2 (9.1%) or group 3 (10.5%). Additional analysis on the rate of subsequent HBV DNA suppression after the ALT elevation had no huge difference among the three groups (60%, 75%, 50%, respectively). Interestingly, the rate of subsequent HBeAg seroconversion after the ALT elevation was 20% and 25% in group 1 and 2 (ropeginterferon alfa-2b arm) but not seen in PEG-IFN alfa-2a arm.

Efficacy

The efficacy data were shown in Table 3 (ITT population). Data of PP population were shown in Supplemental Table 2. In HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, the rate of HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL during treatment and follow-up among the three groups was similar. In HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, the rate of HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL during treatment and follow-up among the three groups was also similar.

With regard of HBsAg reduction over time, in HBeAg-positive patient, the rate of reduction > 1 log10 at FW24 was 0% (0/11), 0% (0/11), and 11.1% (1/9) in group 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In HBeAg-negative patients at FW24, the rate was 10.0% (1/10), 45.5% (5/11), and 30.0% (3/10), respectively.

In HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, the rate of ALT normalization during treatment and follow-up among the three groups was similar.

Trend of HBeAg seroconversion in HBeAg-positive patients treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b

Patients in ropeginterferon alfa-2b groups (both group 1 and 2) experienced earlier time to HBeAg seroconversion than PEG-IFN alfa-2a group (group 3) (Fig. 2). Patients treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b 450 μg (group 2) experienced HBeAg seroconversion starting from treatment week (TW) 16 and those treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b 350 μg (group 1) developed HBeAg seroconversion starting from TW24. In contrast, patients treated with PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg (group 3) experienced HBeAg seroconversion starting from TW48.

At follow-up week 12, the rate of HBeAg seroconversion was 27.3% (3/11) and 36.4% (4/11) in group 1 and group 2, respectively, as compared to 11.1% (1/9) in group 3. One patient in group 1 was treated with Telbivudine after FW12 and withdrawn from study (Table 3).

Table 4 showed the analysis for predictors of HBeAg seroconversion (ITT population). Data of PP population were shown in Supplemental Table 3. Univariate analysis revealed lower baseline HBV DNA level, lower baseline HBeAg level, lower HBsAg at TW12, and higher baseline ALT were associated with HBeAg seroconversion at FW24. However, these predictors had no association with the HBeAg seroconversion rate at FW24 in multivariate analysis. Similar results were also observed in the PP population.

Discussion

Patients treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b 450 μg achieved the earliest time to HBeAg seroconversion (starting from TW16), followed by those treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b 350 μg (starting from TW24). Patients treated with PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg had the latest time to HBeAg seroconversion (starting from TW48). This might be explained by the higher dose of interferon in the ropeginterferon alfa-2b groups, which is supported by the finding of Liaw et al, that the patients receiving PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg achieved HBeAg seroconversion earlier than those receiving 90 μg [16].

The rates of HBeAg seroconversion at follow-up were 36.4% (4/11) in ropeginterferon alfa-2b 450 μg, followed by 27.3% (3/11) in ropeginterferon alfa-2b 350 μg, and 11.1% (1/9) in PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg. The HBeAg seroconversion rate in patients treated with PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg in this study was lower than rates reported in the previous studies (11.1% vs. 32–36.2%) [5, 16]. Compared to the registration trial of PEG-IFN alfa-2a, one possible reason is the mean age of patient in this study is approximately 11 years older than mean age of patients in the previous studies (mean aged 43–45 vs. 32–34 years). This implies that HBeAg seroconversion rate might be even higher in the ropeginterferon alfa-2b groups if the patient population is younger.

In the registration trial of PEG-IFN alfa-2a, around 15% of HBeAg positive patients in PEG-IFN alfa-2a plus placebo group have HBeAg seroconversion at treatment week 24 (TW24) and 27% at TW48 [5]. In our study, in ropeginterferon alfa-2b groups (350 μg and 450 μg), 18.2% and 27.3%, respectively, had HBeAg seroconversion at TW24, 18.2% and 36.4%, respectively, at TW48. Thus, earlier HBeAg seroconversion was observed in ropeginterferon alfa-2b groups at most of the time-point when compared with PEG-IFN alfa-2a of the PEG-IFN alfa-2a registration trial. However, this possibly an earlier HBeAg seroconversion by ropeginterferon alfa-2b deserves further validation in the future trials. Nevertheless, HBeAg seroconversion among HBeAg-positive chronic HBV patients is an important treatment endpoint because it is associated with better long-term outcomes, including higher rate of HBsAg seroclearance, durable clinical remission, and slower rates of progression of liver diseases.

Our study showed that lower baseline HBV DNA level, lower baseline HBeAg level, higher baseline ALT, and lower HBsAg at TW12 were associated with HBeAg seroconversion in univariate analysis. However, these factors had no association with HBeAg seroconversion in multivariate analysis, which might be due to the small sample size of this study. Nevertheless, combination of immune-related parameters, e.g. toll-like receptors or anti-HBc antibody titer, might serve as better predictors for the response to PEG-IFN therapy [17,18,19]. Among the HBeAg-positive patients with HBeAg seroconversion, we observed relationships of mean increased ALT followed by decline of mean HBV DNA, indicating immunological responses to clear the virus.

The finding of the numerically lower incidence of rash in both the groups of ropeginterferon alfa-2b (9.5% and 4.5%, respectively) as compared to PEG-IFN alfa-2a (36.8%) might be explained by either the new formulation or by a more homogenous pegylated interferon isoforms. During the study period, only one serious adverse event (SAE) was observed in ropeginterferon alfa-2b 350 μg treatment group. The patient was hospitalized due to myocardial infarction and was treated by percutaneous intervention. He had the risk factors of smoking and hyperlipidemia. Overall, the majority of TEAEs reported in ropeginterferon alfa-2b groups were observed in PEG-IFN alfa-2a group. In addition, no new or unexpected TEAE was reported for ropeginterferon alfa-2b. One patient in Group 1 experienced acute flare [ALT 591 U/L and AST 252 U/L, with HBV DNA 421,000,000 IU/mL, and HBsAg 38,050.61 IU/mL] at FW12. The investigator decided to prescribe Telbivudine at his discretion, as the patient had discontinued the interferon therapy for 12 weeks.

IFN-α has immunomodulatory and has been used to treat chronic HBV since 1976 [20]. Modification of IFN through the addition of polyethylene glycol molecule leads to improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties and has largely replaced conventional IFN. In 2003, Cooksley et al. [21] for the first time demonstrated PEG-IFN alfa-2a (40 kDa) had improved efficacy over conventional interferon in treating chronic HBV. Albinterferon alfa‐2b is an 85.7 kDa protein consisting of recombinant human IFN alfa‐2b genetically fused to recombinant human albumin and can be administrated every two to four weeks. Although studies had shown the non-inferiority of albinterferon alfa-2b for chronic hepatitis C as compared to PEG-IFN alfa, its use on-market was prohibited by lung toxicities, e.g. fibrosing alveolitis, hemoptysis, bronchospasm or interstitial lung disease [9, 10]. By contrast, ropeginterferon alfa-2b did not show the above adverse events of lung after being exposed to 102 healthy subjects, 214 patients with polycythemia vera (including 127 patients in a phase III study in which 95 of them continuously been treated for 36 months) [22], and 270 patients with chronic viral hepatitis (unpublished data). The safety profile is therefore validated. Furthermore, in the phase III study [22], the drug was well tolerated in an average of 48–67 years old PV patients. Similar benefits are expected in hepatitis B patients, a population growing older worldwide.

There are several limitations of this study. Firstly, the small sample size of this study on ropeginterferon alfa-2b in chronic HBV patients. Small sample size may reduce sensitivity of the analysis, e.g. the effect of ropeginterferon alfa-2b on HBsAg loss; and introduce some attrition bias. Secondly, HBV genotype was not tested in this study. Although HBV genotype had been reported to correlate with clinical outcomes and response to PEG-IFN therapy [23], it has not been widely used clinically. Furthermore, studies had confirmed chronic HBV patients in Taiwan were infected by genotype B and C [24].

The enthusiasm for interferon has recently been revived in many recent clinical trials by combining small molecules with interferon for hepatitis B or D to maximize treatment responses [25]. Interferon would be the backbone of treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis D. Although most of patients with CHB are under NAs treatment, the unmet medical need is that the rate of HBsAg loss is low. Recent many new clinical trials for hepatitis B combine small molecules or other agents with interferon to maximize the therapeutic efficacy [26,27,28,29,30]. We anticipate a renewed interest in interferon as safe and reliable immunomodulator therapy in combination with emerging anti-HBV regimens.

Among the two dose levels of ropeginterferon alfa-2b, the 450 µg had higher cumulative HBeAg seroconversion rate of 36.4% at follow-up period (versus 27.3% in 350 µg), with the time to HBeAg seroconversion earlier at treatment week (TW) 16 in the 450 µg group (versus TW24 in the 350 µg group). In safety, the side effects among the two ropeginterferon alfa-2b groups were comparable, including the rash. However, the rate of ALT elevation was only higher in ropeginterferon alfa-2b 350 μg group (38.1%), while the rate of ALT elevation was similar in ropeginterferon alfa-2b 450 μg and PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg (9.1% versus 10.5%). Due to small case number in this study, final dose selection will need further clinical trials to decide.

In conclusion, this preliminary study revealed that ropeginterferon alfa-2b, although in only half the number of injections, is tolerable with comparable safety and efficacy to PEG-IFN alfa-2a. The results show that patients’ time and visits can be saved, and lays the groundwork in developing this new regimen of interferon-based therapy for chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis D.

References

World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report. Geneva: WHO. 2017. https://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/. Accessed 16 Jun 2020

Chon YE, Park JY, Myoung S-M, Jung KS, Kim BK, Kim SU, et al. Improvement of liver fibrosis after long-term antiviral therapy assessed by fibroscan in chronic hepatitis B patients with advanced fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:882–891

Wu CY, Lin JT, Ho HJ, Su CW, Lee TY, Wang SY, et al. Association of nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy with reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a nationwide cohort study. Gastroenterology 2014;147:143-151.e5

Huang YW, Chayama K, Tsuge M, Takahashi S, Hatakeyama T, Abe H, et al. Differential effects of interferon and lamivudine on serum HBV RNA inhibition in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther (Lond) 2010;15:177–184

Lau GKK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, Marcellin P, Thongsawat S, Cooksley G, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2682–2695

Buster EHCJ, Flink HJ, Cakaloglu Y, Simon K, Trojan J, Tabak F, et al. Sustained HBeAg and HBsAg loss after long-term follow-up of HBeAg-positive patients treated with peginterferon alpha-2b. Gastroenterology 2008;135:459–467

Cheng J, Wang Y, Hou J, Luo D, Xie Q, Ning Q, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b in the treatment of Chinese patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomized trial. J Clin Virol 2014;61:509–516

Huang YW, Hu JT, Hu FC, Chang CJ, Chang HY, Kao JH, et al. Biphasic pattern of depression and its predictors during pegylated interferon-based therapy in chronic hepatitis B and C patients. Antivir Ther (Lond) 2013;18:567–573

Zeuzem S, Sulkowski MS, Lawitz EJ, Rustgi VK, Rodriguez-Torres M, Bacon BR, et al. Albinterferon Alfa-2b was not inferior to pegylated interferon-α in a randomized trial of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1257–1266

Nelson DR, Benhamou Y, Chuang WL, Lawitz EJ, Rodriguez-Torres M, Flisiak R, et al. Albinterferon Alfa-2b was not inferior to pegylated interferon-α in a randomized trial of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 2 or 3. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1267–1276

Colvin RA, Tanwandee T, Piratvisuth T, Thongsawat S, Hui AJ, Zhang H, et al. Randomized, controlled pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of albinterferon in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:184–191

Masarova L, Patel KP, Newberry KJ, Cortes J, Borthakur G, Konopleva M, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a in patients with essential thrombocythaemia or polycythaemia vera: a post-hoc, median 83 month follow-up of an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2017;4:e165–e175

Yacoub A, Mascarenhas J, Kosiorek H, Prchal JT, Berenzon D, Baer MR, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a for polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia resistant or intolerant to hydroxyurea. Blood 2019;134:1498–1509

Chuang WL, Chen PJ, Kao JH, Lee CM, Hsu SJ, Su TH, et al. A phase 2 dose finding study for P1101 + ribavirin in patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. Hepatol Int 2016;10(Suppl):S28

Chuang WL, Chen PJ, Lee CM, Hsu SJ, Kao JH, Su TH, et al. A phase 2 dose finding study for P1101 + ribavirin in patients with chronic HCV genotype 2 infection. Hepatol Int 2016;10(Suppl):S29

Liaw YF, Jia JD, Chan HLY, Han KH, Tanwandee T, Chuang WL, et al. Shorter durations and lower doses of peginterferon alfa-2a are associated with inferior hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion rates in hepatitis B virus genotypes B or C. Hepatology 2011;54:1591–1599

Huang YW, Lin SC, Wei SC, Hu JT, Chang HY, Huang S-H, et al. Reduced Toll-like receptor 3 expression in chronic hepatitis B patients and its restoration by interferon therapy. Antivir Ther (Lond) 2013;18:877–884

Huang YW, Hsu CK, Lin SC, Wei SC, Hu JT, Chang HY, et al. Reduced toll-like receptor 9 expression on peripheral CD14+ monocytes of chronic hepatitis B patients and its restoration by effective therapy. Antivir Ther (Lond) 2014;19:637–643

Fan R, Sun J, Yuan Q, Xie Q, Bai X, Ning Q, et al. Baseline quantitative hepatitis B core antibody titre alone strongly predicts HBeAg seroconversion across chronic hepatitis B patients treated with peginterferon or nucleos(t)ide analogues. Gut 2016;65:313–320

Greenberg HB, Pollard RB, Lutwick LI, Gregory PB, Robinson WS, Merigan TC. Effect of human leukocyte interferon on hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic active hepatitis. N Engl J Med 1976;295:517–522

Cooksley WGE, Piratvisuth T, Lee SD, Mahachai V, Chao YC, Tanwandee T, et al. Peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kDa): an advance in the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat 2003;10:298–305

Gisslinger H, Klade C, Georgiev P, Krochmalczyk D, Gercheva-Kyuchukova L, Egyed M, et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus standard therapy for polycythaemia vera (PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV): a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial and its extension study. Lancet Haematol 2020;7:e196–e208

Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B genotypes correlate with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2000;118:554–559

Huang YW, Lin CL, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Kao JH, Chen DS. Hepatitis B viral genotype in Taiwanese patients with acute hepatitis B. Hepatogastroenterology 2008;55:633–635

Xia Y, Liang TJ. Development of direct-acting antiviral and host-targeting agents for treatment of hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 2019;156:311–324

Bazinet M, Pântea V, Placinta G, Moscalu I, Cebotarescu V, Cojuhari L, et al. Safety and Efficacy of 48 Weeks REP 2139 or REP 2165, Tenofovir disoproxil, and pegylated interferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic HBV infection naïve to nucleos(t)ide therapy. Gastroenterology 2020;158:2180–2194

Yuen MF, Gane EJ, Kim DJ, Weilert F, Yuen Chan HL, Lalezari J, et al. Antiviral activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics of capsid assembly modulator NVR 3–778 in patients with chronic HBV infection. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1392–1403.e7

Wu D, Wang P, Han M, Chen Y, Chen X, Xia Q, et al. Sequential combination therapy with interferon, interleukin-2 and therapeutic vaccine in entecavir-suppressed chronic hepatitis B patients: the Endeavor study. Hepatol Int 2019;13:573–586

Lee JH, Lee YB, Cho EJ, Yu SJ, Yoon JH, Kim YJ. Entecavir plus pegylated interferon and sequential HBV vaccination increases HBsAg seroclearance: a randomized controlled proof-of-concept study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa807.

Wedemeyer H, Schöneweis K, Bogomolov PO, Voronkova N, Chulanov V, Stepanova T, et al. GS-13-Final results of a multicenter, open-label phase 2 clinical trial (MYR203) to assess safety and efficacy of myrcludex B in cwith PEG-interferon Alpha 2a in patients with chronic HBV/HDV co-infection. J Hepatol 2019;70:e81

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients, their families, study investigators, coordinators and nurses who took part in this study. In addition to the authors, the following investigators participated in the study: Chun-Jen Liu, Jia-Horng Kao, Chen-Hua Liu, Chieh-Chang Chen, Sien-Sing Yang, Jui-Ting Hu, Jaw-Ching Wu, Jia-Jang Chang, Chau-Ting Yeh, Yi-Cheng Chen, Chen-Chun Lin, Hsien-Hong Lin, Chia-Chi Wang, Ching-Sheng Hsu, Tai-Chung Tseng, Cheng-Yuan Peng, Wen-Pang Su, Jung-Ta Kao, Sheng-Hung Chen, Yu-Chun Hsu, Hsu-Heng Yen, Shun-Sheng Wu, Chia-Wei Yang, Kai-Lun Shih, Yen-Chih Lin, Chuan-San Fan, Kun-Ching Chou, Pei-Yuan Su, Wan-Long Chuang, Chia-Yen Dai, Jee- Fu Huang, Ming-Lun Yeh, Chuan-Mo Lee, Jing-Houng Wang, Chao-Hung Hung, Chien-Hung Chen, Kuo-Chin Chang, Kwong-Ming Kee, Yi-Hao Yen, Tsung-Hui Hu and Po-Lin Tseng.

The authors thank Weichung Joe Shih, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus in the Department of Biostatistics, Rutgers School of Public Health, The State University of New Jersey for his advice and comments on biostatistics. The authors thank Chungwei Darren Tsai for assistance in preparing the manuscript. This study had been presented at the 68th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, 20—24 October, 2017 in Washington DC, USA (Abstract no. LB-29) and at the International Liver Congress™ of European Association for the Study of the Liver, 11—15 April, 2018 in Paris, France (Abstract no. FRI-328).

Funding

This study was supported by PharmaEssentia Corp.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PJC conceived and designed the study. YWH, CWH, SNL, MLY, CWS, WWS, RNC, CSH, SJH, HCL and PJC recruited patients and collected the data. AQ, KCT and PJC analyzed the data. All authors interpreted the data and were involved in the development, review, and approval of the manuscript. YWH and PJC wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Pei-Jer Chen serves as consultant of PharmaEssentia Corp. Chao-Wei Hsu, Sheng-Nan Lu, Ming-Lung Yu, Chien-Wei Su, Wei-Wen Su, Rong-Nan Chien, Ching-Sheng Hsu, Shih-Jer Hsu, Hsueh-Chou Lai, declare no conflicts of interest. Yi-Wen Huang joins PharmaEssentia Corp. after completion of the study. Albert Qin and Kuan-Chiao Tseng are employee of PharmaEssentia Corp.

Ethical statement

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. This study was registered in Taiwan CDE (No. 1015025937).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, YW., Hsu, CW., Lu, SN. et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b every 2 weeks as a novel pegylated interferon for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int 14, 997–1008 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-020-10098-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-020-10098-y