Abstract

Population ageing is a growing social and health issue in low and lower-middle-income countries (LLMIC). It will have an impact on rising healthcare costs, unaffordable pension liabilities, and changing healthcare demands. The health systems of many LLMICs are unprepared to meet these challenges and highlighting the modifiable factors that may help decrease these pressures is important. This review assessed the prevalence of healthy ageing and the modifiable factors that may promote/inhibit healthy ageing among older people in LLMIC. A systematic search of all articles published from 2000 to June 2022 was conducted in Scopus, PubMed (MEDLINE), and Web of Science. All observational studies reporting the prevalence of healthy ageing and its associations with socio-demographic, lifestyle, psychological, and social factors were examined. Random-effect models were used to estimate the pooled prevalence of healthy ageing, and meta-analyses were conducted to assess the risk/benefit of modifiable factors. From 3,376 records, 13 studies (n = 81,144; 53% of females; age ≥ 60 years) met the inclusion criteria. The pooled prevalence of healthy ageing ranged from 24.7% to 56.5% with lower prevalence for a multi-dimensional model and higher prevalence for single global self-rated measures. Factors positively associated with healthy ageing included education, income, and physical activity. Being underweight was negatively associated with healthy ageing. Almost half of older people in LLMIC were found to meet healthy ageing criteria, but this estimate varied substantially depending on the healthy ageing measures utilized (multi-dimensional = 24.7%; single indicator = 56.5%). The healthy ageing prevalences for both measures are lower compared to that in high-income countries. Developing health policies and educative interventions aimed at increasing physical exercise, social support, and improving socio-economic status and nutrition will be important to promote the healthy ageing of older people in LLMIC in sustainable ways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population Ageing

Globally, there are currently more than one billion adults aged 60 years and older. If population ageing continues following the current trends, approximately 80% of older people will be living in developing countries in the next two to three decades (WHO, 2021). Addressing the health needs of these populations will have an impact on developing countries’ healthcare systems as increased age is associated with a higher prevalence of chronic diseases such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, diabetes, hearing loss, low back pain, depression, and osteoarthritis (Vos et al., 2020). At a societal level, increasing numbers of older adults adds budgetary pressure owing to increased expenditure on medication, increased consumption of health care services, and the cost of people caring for older people. In low and lower-middle income countries (LLMIC) especially, there are often insufficient government resources which are unable to meet individuals’ needs (Lee & Mason, 2017). Improving older people’s functional capacity to enjoy good health and the ability to manage chronic disease, along with continued engagement in work and society, will enable governments’ capacity to meet increased economic, health, and social service demands.

Healthy Ageing Concept

Healthy ageing is often used interchangeably with terms such as ageing well, productive ageing, successful ageing, or active ageing although these concepts may differ slightly in how they are operationalised. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined healthy ageing as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional capacity of older people that enables wellbeing in older age” (WHO, 2020). Health systems need to encourage physical, mental, and social health opportunities so that older persons can live free of prejudice, live independently, and have a good quality of life (Rudnicka et al., 2020).

Healthy ageing has been studied extensively in high-income countries (Daskalopoulou et al., 2017; Moreno-Agostino et al., 2020; Szychowska & Drygas, 2022), but LLMIC were not represented in these reviews. LLMIC is defined as world bank with a GNI per capita less than $4,095 (WorldBank, 2021–2022). In LLMIC, population ageing is experiencing the greatest increases (He et al., 2016), and the modifiable factors associated with healthy ageing may differ from those in developed countries due to differences in socio-demographic and environmental characteristics such as access to services, lifestyle, income, and education, inherent to LLMIC.

Prevalence and Determinants of Healthy Ageing

The prevalence of healthy ageing appears to vary greatly between LLMIC with reported estimates ranging from 7.5% in Nigeria (Gureje et al., 2014), 22.2% in Palestine (Badrasawi et al., 2020) to 83.2% in the Philippines (Tzioumis et al., 2019). This variability may be due to sampling and demographic differences, and the use of varying healthy ageing definitions. The first two studies were operationalized through multi-dimensional models of healthy ageing (e.g., absence of chronic diseases, physical, psychological, and mental functionality) which tend to produce lower prevalence estimates (Badrasawi et al., 2020; Gureje et al., 2014), or derived from single global indicators of self-rated health which tend to produce higher prevalence estimates (Tzioumis et al., 2019). These inconsistent definitions and highly variable prevalence figures impedes our capacity to accurately describe the experience of healthy ageing in LLMIC.

Factors that promote healthy ageing include socio-economic status, lifestyles, or behavioural, psychological, social, and environmental factors (Abud et al., 2022; Daskalopoulou et al., 2017). A few studies in LLMIC have identified modifiable factors for healthy ageing, such as residence, education, marital status, and no social capital (Daskalopoulou et al., 2018; Depp & Jeste, 2006; Omotara et al., 2015), but their findings have not always been consistent. For example, some studies have shown no association between healthy ageing and income (Depp & Jeste, 2006), education (Naah et al., 2020a, 2020b), alcohol consumption (Daskalopoulou et al., 2018), or smoking (Fonta et al., 2017). The reason for these discrepancies may be due to some studies using a single indicator to define healthy ageing while others used broader definitions. These differences have been extensively explored in high-income nations but a better understanding of these issues in LLMIC is needed. Previous reviews (Abud et al., 2022; Daskalopoulou et al., 2017) identified the determinants of healthy ageing around the globe but data from most LLMIC were not representative. So, these reviews provided data from LLMIC, and identifying the modifiable socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics is important for policymakers for designing interventions. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to 1) estimate the prevalence of healthy ageing and 2) identify those modifiable factors associated with healthy ageing in LLMIC.

Methods

Study Protocol and Registration

The protocol for this systematic review with meta-analysis adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) and was registered with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; # CRD42022345455) (Page et al., 2021).

Data Source and Searching Strategy

All authors developed the search strategy, identified key terms, and selected databases. The search method was piloted before the main search. Our key terms included: “risk”, “protect*”, “threat”, “factor*”, “modifiable”, “lifestyle”, “exposure*”, “determinant”, “psycho*”, “social”, “environment”, “enviro”, “health”, “ageing”, “aging”, “healthy”, “successful”, “well”, “active”, “low”, “middle”, “developing”, “countries”, “country”, “region*”, “state*”, “nation*” and “LMIC”. The details of our search strategies for each search engine are described below.

PubMed Search Strategy

(“risk” OR “protect*” OR “threat” OR “Determinants”) AND (“factor*” OR “exposure*” OR “health” OR “Modifiable” OR “Lifestyle” OR “Enviro” OR “Psycholog*” OR “Social”) AND (“healthy Ageing” OR “healthy aging”) OR (Successful Ageing OR “successful aging”) OR (“ Ageing well” OR aging well) OR “aging” or “ageing” (“active Ageing OR active aging”) AND (((“low” OR “middle” OR “developing”) AND ((“countries” OR “country” OR “region*” OR “state*” OR “nation*” OR “LMIC” OR Afghanistan OR “Burkina Faso” OR Burundi OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Congo OR "Democratic Republic of Congo" OR Eretria OR Ethiopia OR Gambia, OR Guinea OR “Guinea-Bissau” OR Korea OR “Democratic people’s Republic” OR Liberia OR Sudan OR Madagascar OR Mali OR Malawi OR Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda OR “Sierra Leone” OR Somali OR “South Sudan” OR “Syrian Arab Republic” OR Togo OR Uganda OR “Yemen Republic” OR Angola OR Algeria OR Honduras OR Philippines OR Soma OR India OR Bangladesh OR Indonesia OR “ Sao Tome Principe” OR Belize OR Iran OR “Islamic Republic” OR Senegal OR Benin OR Kenya OR “Solomon Islands” OR Bhutan OR Kurobuta OR “Sri Lanka” OR Bolivia OR “Kyrgyz Republic” OR Tanzania OR “Cabo Verde” OR “Lao PDR” OR Tajikistan OR Cambodia OR Lesotho OR “Timor-Leste” OR Cameron OR Mauritania OR Tunisia OR Comoros OR Ukraine OR “Micronesia” OR “Congo” OR Mongolia OR Uzbekistan OR” Ivory coast” OR “Cote d’Ivoire” OR Morocco OR Vanuatu OR Djibouti OR Myanmar OR Vietnam OR Egypt OR “Arab Republic” Nepal OR “West Bank” OR “Gaza” OR “El Salvador” OR Nicaragua OR Zambia OR Eswatini OR Nigeria OR Zimbabwe OR Ghana OR Pakistan OR Haiti OR “Papua New Guinea”))). The full data search techniques are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Eligibility Criteria

Articles were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1. Reported on the prevalence of “healthy ageing” or on modifiable factors (sociodemographic, lifestyle, or environmental) related to “healthy ageing”, a multi-dimensional healthy ageing measure (a composite measure of two or more healthy ageing domains) or measure of a single indicator of self-reported health status as good were included. 2. Observational studies and included participants 60 years and above, 3. Were published in English, 4. Were available with full texts, 5. The samples were derived from LLMIC (WorldBank, 2021–2022) and 6. Reviews, meta-analyses, and ecological studies were not included.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of this review was the prevalence of healthy ageing. The second outcome of this review was to identify the modifiable factors that promote healthy ageing in LLMIC populations. After an initial scoping review by the lead researcher, most articles on healthy ageing in LLMIC were limited to two main types of measures of healthy ageing. The first is a multi-dimensional model, generally informed by medical models or Rowe and Kahn’s model of successful ageing (Wahl et al., 2016), which operationalizes healthy ageing as the absence of chronic disease, with no limitations in physical function, and no impairment in mental, social, and cognitive functions, with cut-points for healthy ageing status defined by the study authors. The second type of measure was a single global measure of health (self-rated health, SRH), where good, very good, and excellent SRH were defined by study authors as indicative of healthy ageing. This review included studies that used either indicator to measure the prevalence as well as the potential modifiable factors associated with healthy ageing.

Study Selection

Systematic searches were conducted in Scopus, PubMed (MEDLINE), and Web of Science databases. Articles potentially eligible for inclusion were imported into EndNote V.20, and then exported to the Covidence (Geneshka et al., 2021). Following the removal of duplicates, two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles using the pre-set PEO and eligibility criteria. Then, a full-text review was conducted for the selected studies for further relevance and inclusion. Any disagreements during the screening process were resolved via discussion.

Data Extraction

Two authors independently extracted key data from the included studies. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Meta-Analysis of Statistics and Review Instruments (Porritt et al., 2014) was used to extract data from individual studies. Information extracted from the articles included primary investigator’s name, year of publication, continent, country, study design, sample size, prevalence, adjusted effect size, and the tool used to measure the outcome (healthy ageing). Any discrepancies encountered during information extraction were resolved via discussion.

Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

Two authors independently assessed the study quality using the JBI quality appraisal criteria for both cross-sectional and cohort/longitudinal studies. Studies were scored on a scale of 0–8 and defined as low (< 4), moderate (4–6), and high (7–8) methodological quality (JBI, 2020). Discrepancies were solved through consensus or resolved by consulting a third reviewer if needed. No studies were excluded based on their quality score (Supplementary Table S2 & S3).

Data Analysis

Information including study location, setting, design, sample, age, sex, measurements/tools, response rate, and outcome were extracted and exported to Stata V.17 for meta-analysis. A forest plot summarized and presented the characteristics of the studies included in this review. The prevalence of healthy ageing was pooled across studies using a random effect model to produce a single estimate. The statistics I2 heterogeneity test among the included studies was examined (Higgins, 2011) and I2 values greater than 75%, 50%–75%, 25%–50%, and less than 25% were interpreted as the presence of high, moderate, low, and very low heterogeneity, respectively. The Maximum likelihood estimate, and Laird random-effects model estimated the prevalence of healthy ageing. As the majority of studies reported only adjusted odds ratio (AOR), CIs, and P-values, the logs of AORs were used to determine the pooled association between each modifiable risk factor and participants’ healthy ageing statuses.

Publication Bias

Funnel plots (Ahola et al., 2021) and Egger’s tests (Vandenbroucke, 1998) were used to check the presence of publication bias among the studies included. Trim-and-fill analysis assessed the effect of remaining studies that might have been included and fill imputed studies based on biases corrected pooled prevalence.

Sub-group Analyses

Sub-group analyses were performed to examine differences in the prevalence of healthy ageing across the following factors:

-

i.

Study design: Studies were classified as cross-sectional and longitudinal studies which helps to allow sufficient variation for comparisons between study designs to be made.

-

ii.

Health Ageing Operationalisation: Healthy Ageing outcomes were defined as either self-rated health status (SRH) versus multi-dimensional models to compare differences healthy ageing prevalence between healthy ageing measures.

-

iii.

Study region: Comparisons were made continents from where studies were undertaken.

-

iv.

Sample size: Comparisons between studies with samples sizes of n ≤ 1200 versus n > 1200 was based on the median sample sizes of studies included in the review.

-

v.

Year of the study: A binary variable for year of the study was categorised as articles published before 2020 vs. those after 2020 above.

The results of sub-group analysis were presented in tables with prevalence, 95% CIs and I2 statistics test results. The statistical significance for sub-group analysis results is also determined at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Study Selections

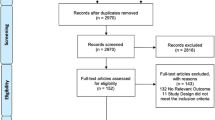

Figure 1 shows that a total of 3,376 research articles regarding modifiable risk factors of healthy ageing in LLMIC were retrieved. After removing 558 duplicate articles a further 2,772 articles were excluded through title and abstract screening leaving 46 studies for full text review. Of those, 33 articles were excluded for not fulfilling the inclusion criteria leaving 13 articles to be considered for the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The 13 studies provided healthy ageing information for 81,144 older adults, with individual study sample sizes ranging from n = 185 to n = 30,639. Just over half of the study participants were females (53%) and almost all articles included both sexes (n = 12). Some studies provided mean age information, while others reported age groups as frequencies and/or percentages. The majority of participants (58.6%) in the studies were within the age range of 60 and 69, and 11.4% were aged 80 + . The studies were predominantly from Asia (n = 7). Healthy ageing prevalence ranged from 7.5% to 41.7% for multi-dimensional models and from 23.5% to 83.2% for models based on single indicators. The majority of articles (n = 11) were cross-sectional studies. The full details of the information regarding the included studies are described in Table 1.

Study Quality Appraisals

The assessment of study quality, based on JBI criteria, suggests that most studies had good methodological quality (Table 1). However, the overall GRADE level of certainty assessment was low. The full details of this information are provided in Supplementary Table S4.

Prevalence of Healthy Ageing in Low and Low-Middle Income Countries

Figure 2 shows the pooled prevalence of healthy ageing in the thirteen studies. The polled prevalence of healthy ageing for usingthe multi-dimensional measure was 24.7% while self-rated health status was 56.5%. High heterogeneity was reported (I2= 99.93%, P < 0.001) and in sub-group analysis, this level of heterogeneity was consistent between key study characteristics including study design (I2 = 96.99%, P < 0.001), sample size (I2 = 98.67%, P < 0.001), and year of study (I2 = 96.49%, P < 0.001) and measuring tools (I2 = 99.93%, P < 0.001).

Publication Bias

Figure 3 shows that there was no evidence of publication bias as observed in the funnel plot or detected by the Egger test (P = 0.409). The Trim fill analysis indicated that there was no difference between observed and observed + imputed model; effect sizes and CIs were equivalent between models (ES = 47.59, 95% CI: 34.09–61.10), suggesting no omitted studies influencing publication bias.

Association between Study Characteristics and Health Ageing

Meta-regression investigated whether study characteristics such as sample size, region or continent, study design, number of people with outcome, and tool used to measure prevalence of healthy ageing were sources of heterogeneity in the prevalence of healthy ageing. Table 2 shows that operationalisation of health ageing was the only study characteristic that was associated with health ageing prevalence.

Modifiable Factors of Healthy Ageing

A review of the studies identified several modifiable factors that promote or inhibit healthy ageing (either using multi-dimensional definition or the single overall health indicator) of older people in LLMIC. Summary results are provided in Table 3 and Fig. 4. Four studies (Debpuur et al., 2010; Fonta et al., 2017; Pengpid & Peltzer, 2021; Tetteh et al., 2019) indicated that high-income were positively associated with healthy ageing. Two studies (Gureje et al., 2014; Pengpid & Peltzer, 2021) reported those who attended at least to a school-level and reported physical activity were positively associated with healthy ageing. Not smoking was not associated with healthy ageing in two studies (Fonta et al., 2017; Gureje et al., 2014) while being underweight reduced the likelihood of being classified as healthy ageing in two other studies (Pengpid & Peltzer, 2021; Tetteh et al., 2019).

Discussion

There is a paucity of data addressing the epidemiology of healthy ageing in LLMIC. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to fill this gap. Two operationalisations have been used to quantify healthy ageing in LLMIC: a multi-dimensional model which focuses on a medical model of successful ageing, and a model based on overall self-rated health. This study found that the prevalence of healthy ageing in LLMIC using the Rowe and Kahn’s Successful Ageing model was substantially lower than in high-income countries, with only 24.7% of older people meeting the healthy ageing criteria. This is contrast with estimates from high-income countries such as Canada and Poland, where the prevalence of healthy ageing is reported to be 42% (Meng & D'arcy, 2014) and 41.8% (Schietzel et al., 2022), respectively. The prevalence estimate based on a global measure of SRH was substantially higher (57.7%) in this sample of LLMIC studies, although still lower than those reported in high-income countries such as the United States and Northern Iceland, where the prevalence of healthy ageing using SRH models is reported to be 73.4% (Axon et al., 2022), and 72.6% (Sigurdardottir et al., 2019), respectively. Overall, for both healthy ageing operationalisations, these findings highlight the lower prevalence of healthy ageing in LLMIC compared to high-income countries.

This study’s findings highlight two major issues in describing healthy ageing prevalence: differences in prevalence can be accounted for by the healthy ageing model/operationalisation applied, and those differences between high and LLMIC countries. Differences between single indicators and multi-dimensional healthy ageing models raise important questions. Are single indicators too broad in definition and capture older adults who are not ageing healthily but who otherwise perceive themselves as ageing well? Or are multi-dimensional models too narrowly focused and fail to capture older adults who are otherwise ageing well despite some deficit in just one domain of functioning? These conceptual arguments need to be reconciled for healthy ageing to inform public health policy. Differences in the prevalence of healthy ageing between LLMIC and high-income countries, regardless of the models utilized, could be attributed to older adults in high-income countries having higher levels of education, physical activity, better access to established healthcare systems, with increased accessibility and usage of technology such as media and internet access (Henriquez-Camacho et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2019; McLean, 2022; WHO, 2018). For this reason, assessing the modifiable factors that affect the wellbeing of older people in LLMIC is essential to improve their health status.

This review of LLMIC studies identified income, education, physical activity, and social support as factors that are positively associated with an increased likelihood of healthy ageing. In contrast, underweight was associated with lower likelihood of healthy ageing, and notably other key modifiable factors (e.g., not smoking) were not found to be related to healthy ageing. That income was positively associated with healthy ageing, confirms with the findings of other systematic reviews (Wagg et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022), which identified that older people who own their homes and report high incomes are more likely to be a healthy ager than those who do not. Poor housing quality and limited income, which prohibits access to health care and services, have deleterious effects on people’s capacity to age healthily. It is therefore crucial to address the causes of older people's economic inequality to increase individuals’ capacity to experience healthy ageing. That education was also associated with increased likelihood of health ageing confirms consistent findings in the literature (Zhang et al., 2022). Those with higher education have opportunities to establish more extensive social networks, develop a better understanding of health and lifestyle choices that may better maintain their health, and to engage in social activities, all of which support healthy ageing. This suggests that public policy needs to recognise that healthy ageing in older adulthood is an outcome of exposures and experiences through the life course, emphasising a life-course perspective to the implementation of public health policies.

This review found physical activity was positively associated with healthy ageing. Previous systematic reviews (Daskalopoulou et al., 2017; Moreno-Agostino et al., 2020; Szychowska & Drygas, 2022) have revealed that older adults who engage in regular physical activity report improved wellbeing, maintenance of a healthy weight, have more energy, and less likely to report chronic disease, cognitive decline, osteoporosis, and sarcopenia. There is also strong evidence that regular physical exercise such as dancing or home exercise can help reduce depression, enhance cognitive function, report better health, and reduce falls risk (Lin et al., 2020).

Receiving social support and participating in community activities were positively associated with healthy ageing. Similarly, previous research has reported that older people who participated in social activities were rated as having better health and wellbeing (Puspitasari et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017) (Li et al., 2014) (Baron et al., 2019). It has been proposed that social support enables individuals to discuss their feelings and worries with friends and family members, which makes it simpler to come up with solutions, receive psychological support from others, and prevent depression and loneliness (Bourassa et al., 2017; Sirven & Debrand, 2008). Thus, older people who received social support and engaged in community activities were found to have improved cognition, general health, and a lower risk of developing chronic diseases (Takács & Nyakas, 2022).

In contrast to those factors that appear to promote healthy ageing, this review identified that being underweight was negatively associated with healthy ageing among older people. This finding contrasts to that of previous research including a global review (Peel et al., 2005), as well as studies conducted in diverse developed nations like Australia (Hodge et al., 2013), America (Ma et al., 2017), and Mexico (Arroyo-Quiroz et al., 2020), which indicated that older adults with normal BMI, and low waist-to-hip ratios were more likely to be healthy agers. In contrast to the benefit of healthy weight, amongst LLMIC samples, it is underweight status that is a risk for not achieving a healthy ageing status. The reason for this is likely to be multi-factorial. Underweight individuals may have weaker immune systems increasing their vulnerability to infections and illnesses that impact their quality of life and longevity (Uzogara, 2016). There is also clear evidence that weight loss is associated with incident dementia and the development of other conditions such as cancer and therefore may reflect pathological processes which are also linked to the risk factors discussed above. Overall, improving nutrition of LLMIC nations is important to address this risk for not experiencing health ageing (Norman et al., 2021).

That smoking status was not associated with healthy ageing is inconsistent with previous systematic reviews (Barragán et al., 2021; Daskalopoulou et al., 2018; Lafortune et al., 2016; Steffl et al., 2015), which found that older people who had never smoked were more likely to be healthy ageing. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is the lack of sufficient coverage in the studies included in the current review that investigated the impact of smoking on the wellbeing of older individuals. Another possible explanation is that tobacco products are often more expensive relative to the average income in LLMIC, and there is less cultural acceptance of smoking in these countries compared to high-income countries (Lee et al., 2020). These factors may contribute to differences in smoking rates and related health outcomes in different regions of the world. Indeed, consistent with this explanation a previous study in LLMIC found that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which is mostly attributable to smoking) was not associated with dementia in some low-income countries (Cherbuin et al., 2019).

Strengths and Limitations of this Review

To our knowledge, this systematic review and meta-analysis is one of the first to synthesize the evidence on modifiable factors that promote healthy ageing of older people in LLMIC. The majority of studies included in this review had low risk of bias, but the overall GRADE level of certainty assessment was low due to the heterogeneity of the included studies. Despite evidence that populations are rapidly ageing in many of these LLMIC, our review identified only limited research in these countries. Despite these limitations, this review provides valuable insights into the current state of knowledge on healthy ageing in LLMIC and highlights the need for more research in this area.

Conclusion

This review has identified, regardless of the model used to assess health ageing, that the prevalence of healthy ageing is lower among community-dwelling older people in LLMIC compared to those in high-income countries. Whilst a number of key factors were associated with the likelihood of reporting healthy ageing, more research specifically focusing on LLMICs with rapidly ageing populations is needed to consistently identify the factors that promote or inhibit healthy ageing. This knowledge can then better inform LLMIC governments address future public health needs of older people. Our review identified that healthy ageing has not been systematically studied in most LLMIC and conducting further large-scale surveys will be important to improve our knowledge and inform public health action. Most importantly, a consensus is required on the best approach to assess healthy ageing to allow for more robust comparisons across population.

Data Availability

The data is available based on request to authors.

References

Abud, T., Kounidas, G., Martin, K. R., Werth, M., Cooper, K., & Myint, P. K. (2022). Determinants of healthy ageing: A systematic review of contemporary literature. Ageing Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(6), 1215–1223.

Ahola, R., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2021). Social support experiences by pupils in finnish secondary school [Article]. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 26(1), 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2021.1991403

Aromataris E, M. Z. (2020). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI 2020. Retrieved 29/02/2023 from Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

Arroyo-Quiroz, C., Brunauer, R., & Alavez, S. (2020). Factors associated with healthy ageing in septuagenarian and nonagenarian Mexican adults. Maturitas, 131, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.10.008

Axon, D. R., Jang, A., Son, L., & Pham, T. (2022). Determining the association of perceived health status among United States older adults with self-reported pain. Ageing and Health Research, 2(1), 100051.

Badrasawi, M., Samuh, M., Khallaf, M., & Abuqamar, M. (2020). Successful ageing among community-dwelling palestinian older adults: Prevalence and association with sociodemographic characteristics, health, and nutritional status. Indian Journal of Public Health, 64(3), 271–276. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_371_19

Baron, M., Riva, M., & Fletcher, C. (2019). The social determinants of healthy ageing in the Canadian Arctic. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 78(1), 1630234.

Barragán, R., Ortega-Azorín, C., Sorlí, J. V., Asensio, E. M., Coltell, O., St-Onge, M.-P., Portolés, O., & Corella, D. (2021). Effect of physical activity, smoking, and sleep on telomere length: A systematic review of observational and intervention studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(1), 76.

Bourassa, K. J., Memel, M., Woolverton, C., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in ageing adults over time: Comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity [Article]. Ageing and Mental Health, 21(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1081152

Carandang, R. R., Shibanuma, A., Asis, E., Chavez, D. C., Tuliao, M. T., & Jimba, M. (2020). “Are Filipinos Ageing Well?”: Determinants of Subjective Well-Being among Senior Citizens of the Community-Based ENGAGE Study [Article]. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(20), 13, Article 7636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207636

Chaurasia, H., Srivastava, S., & Debnath, P. (2021). Does socio-economic inequality exist in low subjective well-being among older adults in India? A decomposition analysis approach [article]. Ageing International. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-021-09453-7

Cherbuin, N., Walsh, E. I., & Prina, A. M. (2019). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and risk of dementia and mortality in lower to middle income countries. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 70(s1), S63–S73.

Daskalopoulou, C., Stubbs, B., Kralj, C., Koukounari, A., Prince, M., & Prina, A. M. (2017). Physical activity and healthy ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Research Reviews, 38, 6–17.

Daskalopoulou, C., Stubbs, B., Kralj, C., Koukounari, A., Prince, M., & Prina, A. M. (2018). Associations of smoking and alcohol consumption with healthy ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. British Medical Journal Open, 8(4), e019540.

Debpuur, C., Welaga, P., Wak, G., & Hodgson, A. (2010). Self-reported health and functional limitations among older people in the Kassena-Nankana District, Ghana. Glob Health Action, 3. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v3i0.2151

Depp, C. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2006). Definitions and predictors of successful ageing: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(1), 6–20.

Fonta, C. L., Nonvignon, J., Aikins, M., Nwosu, E., & Aryeetey, G. C. (2017). Predictors of self-reported health among the elderly in Ghana: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0560-y

Geneshka, M., Coventry, P., Cruz, J., & Gilbody, S. (2021). Relationship between green and blue spaces with mental and physical health: A systematic review of longitudinal observational studies [Review]. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(17), Article 9010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179010

Gureje, O., Oladeji, B. D., Abiona, T., & Chatterji, S. (2014). Profile and determinants of successful ageing in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62(5), 836–842. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12802

He, W., Goodkind, D., & Kowal, P. R. (2016). An ageing world: 2015. In: United States Census Bureau Washington, DC.

Henriquez-Camacho, C., Losa, J., Miranda, J. J., & Cheyne, N. E. (2014). Addressing healthy ageing populations in developing countries: Unlocking the opportunity of eHealth and mHealth. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology, 11(1), 1–8.

Higgins, J. (2011). Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1. 6.

Hodge, A. M., English, D. R., Giles, G. G., & Flicker, L. (2013). Social connectedness and predictors of successful ageing. Maturitas, 75(4), 361–366.

Huang, N. C., Chu, C., Kung, S. F., & Hu, S. C. (2019). Association of the built environments and health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study [Article]. Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02199-5

Lafortune, L., Martin, S., Kelly, S., Kuhn, I., Remes, O., Cowan, A., & Brayne, C. (2016). Behavioural risk factors in mid-life associated with successful ageing, disability, dementia and frailty in later life: A rapid systematic review. PLoS ONE, 11(2), e0144405.

Lee, C., Gao, M., & Ryff, C. D. (2020). Conscientiousness and smoking: Do cultural context and gender matter? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1593.

Lee, R., & Mason, A. (2017). Cost of aging. Finance & development, 54(1), 7.

Li, C. I., Lin, C. H., Lin, W. Y., Liu, C. S., Chang, C. K., Meng, N. H., Lee, Y. D., Li, T. C., & Lin, C. C. (2014). Successful ageing defined by health-related quality of life and its determinants in community-dwelling elders. BMC Public Health, 14, 1013. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1013

Lin, Y. H., Chen, Y. C., Tseng, Y. C., Tsai, S. T., & Tseng, Y. H. (2020). Physical activity and successful ageing among middle-aged and older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ageing (Albany NY), 12(9), 7704–7716. https://doi.org/10.18632/ageing.103057

Ma, W., Hagan, K. A., Heianza, Y., Sun, Q., Rimm, E. B., & Qi, L. (2017). Adult height, dietary patterns, and healthy ageing. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 106(2), 589–596.

McLean, S. (2022). Understanding the evolving context for lifelong education: Global trends, 1950–2020. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 41(1), 5–26.

Meng, X., & D’arcy, C. (2014). Successful ageing in Canada: Prevalence and predictors from a population-based sample of older adults. Gerontology, 60(1), 65–72.

Moreno-Agostino, D., Daskalopoulou, C., Wu, Y.-T., Koukounari, A., Haro, J. M., Tyrovolas, S., Panagiotakos, D. B., Prince, M., & Prina, A. M. (2020). The impact of physical activity on healthy ageing trajectories: Evidence from eight cohort studies. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 1–12.

Naah, F. L., Njong, A. M., & Kimengsi, J. N. (2020a). Determinants of active and healthy ageing in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Cameroon. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3038.

Naah, F. L., Njong, A. M., & Kimengsi, J. N. (2020b). Determinants of Active and Healthy Ageing in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Cameroon [Article]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 24, Article 3038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093038

Norman, K., Haß, U., & Pirlich, M. (2021). Malnutrition in older adults—recent advances and remaining challenges. Nutrients, 13(8), 2764.

Omotara, B. A., Yahya, S. J., Wudiri, Z., Amodu, M. O., Bimba, J. S., & Unyime, J. (2015). Assessment of the determinants of healthy ageing among the rural elderly of North-Eastern Nigeria. Health, 7(06), 754.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., & Brennan, S. E. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906.

Peel, N. M., McClure, R. J., & Bartlett, H. P. (2005). Behavioral determinants of healthy ageing. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(3), 298–304.

Pengpid, S., & Peltzer, K. (2021). Successful ageing among a national community-dwelling sample of older adults in India in 2017–2018. Science and Reports, 11(1), 22186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00739-z

Porritt, K., Gomersall, J., & Lockwood, C. (2014). JBI’s systematic reviews: Study selection and critical appraisal. AJN the American Journal of Nursing, 114(6), 47–52.

Puspitasari, M. D., Rahardja, M. B., Gayatri, M., & Kurniawan, A. (2021). The vulnerability of rural elderly Indonesian people to disability: an analysis of the national socioeconomic survey [Article]. Rural and Remote Health, 21(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH6695

Rudnicka, E., Napierała, P., Podfigurna, A., Męczekalski, B., Smolarczyk, R., & Grymowicz, M. (2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas, 139, 6–11.

Schietzel, S., Chocano-Bedoya, P. O., Sadlon, A., Gagesch, M., Willett, W. C., Orav, E. J., Kressig, R. W., Vellas, B., Rizzoli, R., & da Silva, J. A. (2022). Prevalence of healthy ageing among community dwelling adults age 70 and older from five European countries. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 1–11.

Sigurdardottir, A. K., Kristófersson, G. K., Gústafsdóttir, S. S., Sigurdsson, S. B., Arnadottir, S. A., Steingrimsson, J. A., & Gunnarsdóttir, E. D. (2019). Self-rated health and socio-economic status among older adults in Northern Iceland. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 78(1), 1697476.

Sirven, N., & Debrand, T. (2008). Social participation and healthy ageing: An international comparison using SHARE data. Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2017–2026.

Srivastava, S., Debnath, P., Shri, N., & Muhammad, T. (2021). The association of widowhood and living alone with depression among older adults in India. Science and Reports, 11(1), 21641. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01238-x

Srivastava, S., & Muhammad, T. (2020). Violence and associated health outcomes among older adults in India: A gendered perspective [Article]. Ssm-Population Health, 12, 10, Article 100702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100702

Steffl, M., Bohannon, R. W., Petr, M., Kohlikova, E., & Holmerova, I. (2015). Relation between cigarette smoking and sarcopenia: Meta-analysis. Physiological Research, 64(3), 419.

Szychowska, A., & Drygas, W. (2022). Physical activity as a determinant of successful ageing: A narrative review article. Ageing Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(6), 1209–1214.

Takács, J., & Nyakas, C. (2022). The role of social factors in the successful ageing–Systematic review. Developments in Health Sciences, 4(1), 11–20.

Tetteh, J., Kogi, R., Yawson, A. O., Mensah, G., Biritwum, R., & Yawson, A. E. (2019). Effect of self-rated health status on functioning difficulties among older adults in Ghana: Coarsened exact matching method of analysis of the World Health Organization’s study on global AGEing and adult health, Wave 2. PLoS ONE, 14(11), e0224327.

Tzioumis, E., Avila, J., & Adair, L. S. (2019). Determinants of successful ageing in a cohort of Filipino women [Article]. Geriatrics (Switzerland), 4(1), Article 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4010012

Uzogara, S. G. (2016). Underweight, the less discussed type of unhealthy weight and its implications: A review. American Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Research, 3(5), 126–142.

Vandenbroucke, J. P. (1998). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Experts' views are still needed. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 316(7129), 469.

Vos, T., Lim, S. S., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi, M., Abbasifard, M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., & Abdelalim, A. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222.

Wagg, E., Blyth, F. M., Cumming, R. G., & Khalatbari-Soltani, S. (2021). Socioeconomic position and healthy ageing: A systematic review of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [Review]. Ageing Research Reviews, 69, Article 101365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101365

Wahl, H.-W., Deeg, D., & Litwin, H. (2016). Successful ageing as a persistent priority in ageing research. In (Vol. 13, pp. 1–3): Springer.

WHO. (2018). ACTIVE: a technical package for increasing physical activity.

WHO. (2020). Healthy ageing and functional ability. 1. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/healthy-ageing-and-functional-ability. Accessed 3 Feb 2022.

WHO. (2021). Ageing and health https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed 3 Feb 2022.

Win, H. H., Nyunt, T. W., Lwin, K. T., Zin, P. E., Nozaki, I., Bo, T. Z., Sasaki, Y., Takagi, D., Nagamine, Y., & Shobugawa, Y. (2020). Cohort profile: Healthy and active ageing in Myanmar (JAGES in Myanmar 2018): A prospective population-based cohort study of the long-term care risks and health status of older adults in Myanmar. British Medical Journal Open, 10(10), e042877. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042877

WorldBank. (2021–2022). New World Bank country classifications by income level. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2021-2022. Accessed 3 Feb 2022.

Yang, L., Griffin, S., Khaw, K.-T., Wareham, N., & Panter, J. (2017). Longitudinal associations between built environment characteristics and changes in active commuting. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–8.

Zhang, H., Chen, X., Xie, F., Yang, B., Zhao, F., & Quan, Y. (2022). Factors influencing successful ageing in middle-aged and older adults in developing countries: A meta-analysis. Ageing Commun, 4(3), 17.

Zin, P. E., Saw, Y. M., Saw, T. N., Cho, S. M., Hlaing, S. S., Noe, M. T. N., Kariya, T., Yamamoto, E., Lwin, K. T., & Win, H. H. (2020). Assessment of quality of life among elderly in urban and peri-urban areas, Yangon Region. Myanmar. Plos One, 15(10), e0241211.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The lead author (AB) was support by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB and RB contributed to conception of the research protocol, study design, quality assessment, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation, and draft of the manuscript. NC and NB contributed to study design, reviewing, interpretation of the data, and editing the manuscript. The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Computing Interest

The authors declared that there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethic Approval

The data were obtained from secondary sources, and no institutional ethics approval was required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Belachew, A., Cherbuin, N., Bagheri, N. et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Socioeconomic, Lifestyle, and Environmental Factors Associated with Healthy Ageing in Low and Lower-Middle-Income Countries. Population Ageing 17, 365–387 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-024-09444-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-024-09444-x