Abstract

In Ghana, the ageing population is growing at a fast pace amidst challenging socioeconomic environment. As such, the health of elderly persons in Ghana is of emerging concern and of high priority to the Government. In this study, we seek to measure health inequality among elderly persons in Ghana to determine its existence and explore the factors driving it. Data for the study were drawn from the World Health Organization (WHO)‘s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE Wave 1) and analyzed using STATA and a Distributive Analysis Stata Package (DASP) installed in STATA. Health inequality was measured using concentration curves and concentration index (CI). Furthermore, a regression-based approach was used to determine factors associated with health inequality and their estimated contributions to health inequality. The CI for poor SRH was −0.059 indicating greatest poor health among the poor. The highest contributors to health inequality were presence of at least a chronic condition (63.4%), followed by the age group 70 years and above (26.6%), being single (13.9%), poor (3.9%) and uneducated (0.3%). The probability of reporting poor health was higher with increasing age (Coeff = 0.27, p < 0.05), having at least a chronic condition (Coeff = 0.34, p < 0.05), being single (Coeff = 0.14, p < 0.05) and being poor (Coeff = 0.17, p < 0.05). The results show that health inequality exists among the elderly in Ghana and that poor health was greatest among the poor. Socioeconomic, demographic and health related factors are associated with health inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Health inequality can be defined as differences, variation and disparities in achieving health across a group of people (Kawachi et al. 2002). These disparities or variations in health status is seen across age, social and ethnic groups. Health inequality has become a major public health concern, as most countries seek to reduce health inequalities across groups by putting in place public health policies that will improve the health of individuals (Szreter and Woolcock 2004; Bradby 2008). Whereas most developed countries have envisaged this problem of health inequality and made efforts to address this issue, the journey in Africa has been so far slow. The slow progress could be explained, first from poor understanding of health inequality and its interpretation by most researchers. Secondly from lack of motivation by governments of most developing countries in understanding and addressing this critical issue of health disparities (Rispel and Palha de Sousa 2009).

Social determinants have been shown from previous studies to affect the health status of individuals (Muntaner et al. 2009). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) social determinant framework, these are circumstances which people are born, grow, live and work (World Health Organization 2008). Solar and Irwin (2010) found that the causal pathway of health inequality across individuals can arise from three inter-related theories. They include firstly, the ‘psychosocial/behavioral’ theory in which case, different behavioral pattern or social stresses exposes individuals to diseases. Secondly, the ‘social causation’ theory whereby individual health state determines one’s socioeconomic status, for example, the healthy are of high socioeconomic status (SES) and the unhealthy are of low social status. Thirdly, ‘life-course factors’ which include a multifaceted range of exposures over a period including low childhood educational attainment, low birth weight babies from poor maternal nutrition, continual exposure to environmental toxins among others. Other factors that affect individual health include, housing, economic, financial, healthcare access as well as the built in environmental. Health inequality exists when society falls short of moderating socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals through social and economic policies as well as political will. This means improving the living conditions of individuals; reducing inequitable distribution of wealth and power, providing opportunities for at least basic education, employment, and access to health care among others.

The population of the elderly in Africa has led to a growing need to bridge the research gap in understanding issues that affect the health of the elderly and raise awareness for possible policy intervention (Suzman 2010). Consistent with literature across some African countries that highlight inequality in health, poor individuals experience worst health outcomes than the rich. A study carried out in Nigeria found that self-reported health (SRH) was worst among elderly persons with low socioeconomic status (SES) compared to those of high SES (Eme Ichoku et al. 2011). In Kenya, a study done to assess the inequalities that exist in the society found that water supply, solid waste management, food environments, housing and health care services and transportation were the main determinants of health inequality (Muchukuri and Grenier 2009). Similarly, a study in South Africa revealed that predictors of functional disabilities which can be used as an outcome measure for health inequality among older men and women where age, existing chronic conditions, lack of education (Phaswana-Mafuya et al. 2013). In other African countries, lack of social support, depression and low socioeconomic status which are evidence of psychological stress, have been shown to increase the risk of heart conditions which worsens the state of being healthy (Haley et al. 2010).

In the Ghanaian context, most of Ghanaian elderly have little or no education. Also, nine out of ten economically active elderly persons in Ghana are self-employed while 5.8% are employed in the formal sector (Ghana Statistics Service 2013). This implies that many elderly persons over the years may have low earnings or have little or no social security and personal savings for their upkeep as they age. Disparities in health may result from financial insecurity as some elderly persons may take care of their health needs better than others. Additionally, although the Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) exempts elderly persons above 70 years from paying the premium, enrollment rates are higher in urban than rural areas and relatively better off households (Jehu-Appiah et al. 2011). In such instance, there may be increase access to healthcare services and thus better health for the rich compared to the poor. A study also found that elderly Ghanaians in rural areas were more likely to suffer from chronic conditions than their urban counterparts (Ayernor 2012). It could be from financial constrains or limited access to specialized care in the rural areas. The fact remains that these circumstances are prerequisites to unequal distribution of health.

Our study focuses on the elderly in Ghana because they have been neglected in terms of health interventions (de-Graft Aikins 2007). Previous studies have measured socioeconomic inequality in access to healthcare and found that the poor had limited access to healthcare services in Ghana (Saeed et al. 2016). Another study showed that NCDs were more prevalent among rich elderly persons in Ghana (Kunna et al. 2017). While these studies have documented inequality in the prevalence of NCDs and access to healthcare in the country, this is one of the few studies that measures health inequality among elderly persons in Ghana using SRH. Study findings will highlight target areas for policy makers to improve the health of elderly persons. The aim of this paper is to determine the existence of elderly health disparities and understand how a range of social, economic and health related factors impact on elderly health.

Materials and Methods

We used secondary data obtained from a national Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) Wave 1. This study was conducted in Ghana from 2007 to 2008 by WHO. The SAGE study was approved by WHO ethical review process and interviewers obtained written informed consent from participants. Data that was already in public domain was made available upon online request.

The study involved all ten administrative regions of Ghana. Two hundred and fifty-one (251) census enumerated areas selected from urban and rural settlements were used as the sampling frame. These areas were selected based on the size of the population of the elderly in that area. Twenty households were randomly selected from each enumerated area. Over 5000 of elderly persons aged 50 years and above were selected from each household, and individuals between the ages of 18–24 years were selected as proxies. The study defines the elderly as those over 59 years based on the official age of retirement in Ghana. The sample size was reduced to 2613 respondents after excluding missing data on the health outcome variable. Data was collected by face-to-face interviewer administered questionnaires to each household and individual respondent.

Dependent Variable

In measuring inequality, we used self-reported health as the outcome measure. Research has shown that SRH is a measure of subjective well-being among elderly persons (Adjei et al. 2017) and according to Jylhä (2009), it predicts morbidity and mortality. Respondents were asked the question “How do you rate your health today?” The responses were based on a 5-point scale which includes: “Very good” (1); “Good” (2); “Fair” (3); “Bad” (4); and, “Very bad” (5). Based on previous studies, the health variable was regrouped into a binary outcome 0 and 1, with 0 representing responses 1 to 3 (very good/good and fair) as good health and 1 representing responses 4 and 5 (poor/very poor) as poor health (Debpuur et al. 2010; Jepsen et al. 2014).

Independent Variable

For decomposition, all explanatory variables were dichotomized. The variables include;

- 1.

Demographic factors such as age, sex, marital status. Following a similar classification of the age variable by Goli et al. (2014), two groups were formed for comparison: the young old (60–69 years) coded 0; the old - old (70 years and above) coded 1. For marital status, respondents were coded 0 if married and 1 if single. The single category composed of never married, separated, divorced or widowed.

- 2.

Socioeconomic factors included were income, education and work status. The SAGE study measured income as household level income. Income was ranked into five quintiles (very low, low, middle, high and very high-income quintiles). We regrouped the quintiles into two groups. The first group is defined as non-poor if respondents belonged to the last two income quintiles (high and very high-income quintiles), coded as 0. And the very low, low and middle-income quintiles defined as poor, coded 1. Education status was grouped into literate for those who had been to school, coded 0 and non-literate for those who had never been to school, coded 1. In terms of lifetime work status, two categories were formed; never worked coded 1 and previously worked in any of the following sectors, private, public and informal sector, coded 0.

- 3.

Other independent variables assessed were health insurance status (insured/uninsured) coded 0 if insured or 1 if otherwise. Place of residence (urban/rural) coded 0 if urban and 1 if otherwise. The presence of any of the eight chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, angina, stroke, chronic lung disease, depression and asthma) was coded 1 and 0 if absent.

Statistical Analysis

STATA version 13® was used in carrying out the data analysis as well as DASP version 2.3 installed in STATA. First, health inequality was measured by plotting a concentration curve and calculating the concentration index (CI). The concentration curve gives a visual representation of the extent of inequality in SRH. The cumulative percent of the outcome variable, poor self-reported health on its y-axis was plotted against the cumulative percent of the SES defined as household income on the x-axis, ranked from the lowest SES to the highest SES. Across the graph is a diagonal line that represents equality of health status across the group of elderly persons. Poor health is said to be concentrated among those of low SES if the curve lies above the line of equality. On the other hand, if the curve lies below the line of equality, poor health is said to be concentrated among the privileged or those of high SES (Sozmen and Belgin 2014).

The next step involved calculating the concentration index defined as twice the area between the concentration curve and the line of equality, taking on values between −1 and 1. A negative or positive sign indicates that the health variable is concentrated among the poor or the rich, respectively. The further away this value is from 1, the less inequality is said to exist. In the same way, the closer this value is to 1, the greater the inequality among the group of individuals. The formula for calculating concentration index is as shown below,

where C represents the overall index, h is the health outcome variable and μ is its mean and r the fractional rank by income (O’donnell et al. 2008).

Additionally, a decomposition analysis was carried out to determine how much each independent variable contributed to the total inequality. To assess the factors or variables associated with inequality in SRH, a probit model was estimated. The dependent variable was SRH when poor/very poor health = 1, and very good/good/fair health = 0. Based on previous research (Yiengprugsawan et al. 2007; Goli et al. 2014; Brinda et al. 2016), SRH was regressed against its determinants (k) to determine the coefficients of the probit model (Bk). Secondly, the mean of the health outcome measure and the mean of its determinants (μ and Xk) were calculated. This was followed by calculating the CIs of the determinants (Ck) in relation to SRH. Next, the elasticity of the health variable was calculated by multiplying the coefficients with the weighted mean of the corresponding determinants and dividing by the population mean (BkXk/μ). Finally, the contributions to inequality were quantified by multiplying the elasticity by the CIs of each determinant (BkXk/μ) Ck, and the percentage contribution by dividing these values with the overall CI of the population (BkXk/μ) Ck/C. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the elderly. Overall, 579 (22.1%) respondents rated their health as poor, 2034 (77.9%) as good. About 54% of the elderly aged 70 years and above were females. On the other hand, there were more males in the younger age category (54.3%) than females (45.6%). Most females (58.2%) reported poor health compared to males (41.8%). Of the 1268 respondents that were married, 81.8% were males. A great number of females (80.9%) were single (that is, either widowed or divorced). It is not unusual to find elderly men in Ghana remarry after a divorce or the loss of a spouse. The women on the other hand often remain single throughout life given the same circumstance. In terms of education, a higher proportion of educated respondents were males (67.3%). Large family size, socio-cultural and gender preferences were some of the factors that hindered female education in the past (Ghana statistics Service 2013). Almost the same proportions of elderly men and women (50%) have had some form of employment in a lifetime. The informal sector which include agricultural, sales, fishery activities contributes highest to the labor force and employed 9 out of 10 elderly persons.

A higher proportion of elderly men lived in the rural areas (53.4%) while most females (56.1%) lived in urban areas. Most females involved in sales activities prefer to live in highly populated urban areas to make ends meet. The elderly males on the other hand retire to the villages and engage in farm activities. Fifty three percent of low income earners were females while on the other hand, 54% of high income earners were males. Lastly, about 59.7% females reported at least one chronic conditions compared to a fewer proportion of men (40.3%).

Figure 1 illustrates the concentration curve which provides a visual representation of inequality in self-reported health across the elderly population. The curve lies above the line of equality indicating that poor health is more prevalent among the elderly with low socioeconomic status.

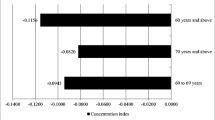

Table 2 shows the overall estimated concentration index for the study which was −0.059. The negative concentration index implies a pro-poor inequality. That is, poor health is suffered most among the poor elderly. Most elderly singles, non-literates and the uninsured belonged to the poorest quintiles. A great number of respondents with chronic conditions were in the richest quintiles.

Decomposing the socioeconomic inequalities in SRH, poor health was greatest among those aged 70 years and above (CI = −0.049), those with the presence of a chronic condition (CI = −.0.87), the uneducated (CI = −0.002), those with no health insurance (CI = −0.059), living in a rural area (−0.02) as well as being single (CI = −0.047) and poor (CI = −0.02). Further decomposing the CIs into each factor’s contribution to health inequality, it was observed that the major contributors to health disparities were from the following variables; presence of chronic condition (63.4%), age category 70 and above (26.6%), single (13.9%), and being poor (3.9%). Education status contributed as low as 0.3%. Work status, health insurance and place of residence contributed less to inequality as shown by the negative signs. The decomposition results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 again shows that the probability of reporting poor health was higher with increasing age, 70 years and above (Coeff = 0.27, p < 0.05). Elderly persons who were single were more likely to report poor health compared to those who were married (Coeff = 0.141, p < 0.05). In a similar way, poor respondents had an increased chance of reporting poor health unlike the non-poor (Coeff = 0.173, p < 0.05). Additionally, the probability of declaring poor health was higher among those who reported one or more than one chronic conditions (Coeff = 0.342, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Our study has shown that health inequality exists among the elderly in Ghana and that poor health is greatest among the poor. In decomposing the concentration index, we found that health inequality was experienced most among those aged 70 years and above, single respondents, those with poor income status, referred to as the poor, and elderly persons with chronic conditions. Our findings are in concordance with other studies that have shown that poor health is often experienced by the least advantaged in the society (Fernandez-Martinez et al. 2012; Sözmen et al. 2012; Fonta et al. 2017). The consequences of poor health is a major setback to societal growth. It not only predisposes individuals and families to poverty given the high medical costs often incurred but causes a downward spiral of government expenditure in health. Thus investing in health is an economic asset (WHO 2003).

Although life expectancy has increased for both men and women in Ghana, this study shows that women tend to live longer as about 54% of the elderly aged 70 years and above were females. Inequality in health tend to increase in the older aged category, contributing 26% to the total inequality observed. Existing studies have found similar findings where individuals report worst health at older age (Molarius et al. 2007; Haseen et al. 2010). The natural ageing process alone is often associated with functional limitations, poor health states, personal losses as well as a weakened immune state. Accumulation of these life stresses over time will lead to inequality in health states particularly worst for the older age group. Furthermore, research shows that some elderly persons still work post retirement, prior to reaching the age of 70 (Sacker et al. 2005). In such instance, they may have better socioeconomic potential and enjoy better health than their older counterparts not working. In Ghana old age is often associated with financial dependence on family members due to retirement from active work. Additionally, the near-collapse of the traditional family system in the country tends to worsen the situation of the elderly (Mba 2010). Elderly persons in such difficult instances strive to survive on their own and understandably more likely to have poorer health.

We find that marital status increases health inequality by about 14%. Elderly respondents who were single were more likely to report poor health compared to those who were married. This finding is supported by previous work by Debpuur et al. (2010) who found that single persons in Ghana aged 50 years and above were more likely to report poor health. Elderly men lacking spousal support are often exposed to poor diet, undisciplined lifestyle, inability to carry out house chores and take care of personal needs. Evidence further shows that elderly persons in relationships are more likely to report better health specifically from psychosocial well-being (Huijts and Kraaykamp 2011; Maniecka-Bryla et al. 2013).

Our analysis again shows that income poverty had a positive impact on health inequality. In other words, poor health was notably greatest among the poor. Income poverty is an influential trajectory to poor health. The odds of reporting poor health among low income earners in China were three times higher compared to reporting poor health among high income earners (Feng et al. 2012). Studies in Brazil have also shown a similar association between low income and poor health (Santiago et al. 2010; Fillenbaum et al. 2013). A stable source of income at old age increases an individual’s social status and thus living conditions. Most elderly persons in Ghana are in low paid jobs with little or no pension. At the time of this study (2008/2009), Ghana’s economic growth was at its best with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of 6.5 in 2007 to 8.4 in 2008 (Cooke et al. 2016). However, these gains are inequitably distributed with the poor experiencing less than 1% of the economic growth (Ghana statistical service 2010). For this reason, some social protection programs like national cash transfer Livelihood Empowerment against Poverty (LEAP), were instituted by the government to improve the socioeconomic status of poor households. The small-scale nature of the program unfortunately limits its nationwide impact on households. Thus, the prospect of better health among the elderly poor in Ghana can still be achieved if living standards are improved through large scale social programs.

The presence of chronic conditions contributed highest (63%) to the health inequality observed in this study and poor health was worst off among those with chronic conditions. Studies have shown similar findings (Golini and Egidi 2016; Foebel et al. 2017). In high income countries, evidence shows that NCDs are prevalent among those with low SES. Such vulnerabilities may be associated to poor access to healthcare, psychosocial stress, lack of awareness and control of NCDs (Lloyd-Sherlock et al. 2017). However, despite these concurrent findings, a cross country study in six countries found that hypertension was more prevalent among rich elderly Ghanaians (Stringhini et al. 2016). This could be attributed to easy access to healthcare and hence higher chances of being aware of health status or better still, high consumption of fat-laden diets as well as sedentary lifestyle (Saeed et al. 2016). This finding implies that self-report status as a measure of wellbeing could be prone to some bias. However, according to Bauman et al. (2010), less difference in social pattern of hypertension in SSA exists. In other words, NCDs are most experienced in all groups irrespective of social pattern. In this regard, interventions for NCD risk reduction should include all persons regardless of SES. These contrary findings notwithstanding, self-reported status is useful in providing information on patient perspective of health.

It is well documented that the burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is on the rise in developing countries (Aboderin 2010; Shadmi et al. 2011; Hosseinpoor et al. 2012; Wu et al. 2013). Non-communicable diseases may be from lifetime exposure to detrimental health determinants and modifiable causes of diseases. In more advanced societies, the health system is more strengthened to take care of the healthcare needs of elderly population together with a good policy environment for the elderly (Fernández et al. 2009). Therefore, despite high NCD prevalence among elderly persons in developed countries, their health needs are well taken care of through a well-structured health system and good policies. In Ghana, the existing policy for elderly persons is yet to be implemented. With the level of poverty in most developing countries, elderly persons with chronic conditions go through debilitating conditions to take care of their health needs.

The study found no significant difference in SRH among elderly persons who were under a health insurance scheme and those who were uninsured. This is rather not surprising given that old age is already a predisposing factor to ill health, and as such, elderly persons are more likely to report poor health, irrespective of their health insurance status.

Limitations

Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, a causal relationship between poor health status and all the independent variables cannot be sufficiently established. However, this study will serve as a platform for future cohort studies on social determinants and poor health. Secondly, self-reported health is usually not seen as the best measure of health status across a population. It is subjective and may have some reporting heterogeneity. Although several studies have used this measure and have made robust contributions to policy (Hanibuchi et al. 2010; French et al. 2012), it is important for scholars to use other measures of measuring health differences to avoid this bias. Household income was used as one of the measures of SES. Income is not the best measure of SES as individuals in developing countries do not often reveal their true income. Lastly, although other factors like lifestyle (smoking, alcohol, consumption etc.) that could have contributed to inequality were not included in the study. It is worth while exploring their role in health inequality in future studies in Ghana as well.

Conclusion

Health inequality is prevalent among elderly persons aged 70 years and above, single, poor and with at least one chronic condition. This study clearly finds that socially and economically disadvantaged individuals experience worst health outcomes at old age. The problem of inequality in health among elderly persons is of growing public health concern, first, because of their increasing number, and second because population ageing is happening in Ghana amidst unequal economic growth. This study is to pave the way for future studies to measure and monitor health inequality in subsequent years.

The Government of Ghana should bear in mind that health inequality exists and has the propensity to increase if adequate measures are not taken. Attempts should be made to prevent the inequality gap from widening. Local programs that aim at improving household livelihood and economic status should be scaled up to national level and amalgamated into a single platform for better implementation and monitoring. Social programs should engage elderly persons in community development activities, particularly those who are single. Such pro-activities can reduce loneliness and dissatisfaction among elderly persons and thus improve health. The burden of chronic diseases should be of priority to Ghanaian policy makers and appropriate strategies to tackle NCDs be reinforced. Government should work through a multi-sectoral approach in involving the health sector, social and financial sectors, to prevent the gap of health inequality from widening.

In conclusion, government should act through these social and health determinants by moderating them in the society to achieve a near equal social status and hence a better health status across the population. Protecting the health of elderly persons will reduce government expenditure on healthcare and disability funds.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that supports the conclusion from this study is available at SAGE website http://www.who.int/healthinfo/sage/en/. Applications are made through the WHO Multi-Country Studies Data Archive website http://apps.who.int/healthinfo/systems/surveydata/index.php/catalog.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Concentration Index

- DASP:

-

Distributive Analysis Stata Package

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- LEAP:

-

Livelihood Empowerment against Poverty

- NCD:

-

Non-Communicable Disease

- SAGE:

-

Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic Status

- SSA:

-

sub-Saharan Africa, Self-Reported Health

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization.

References

Aboderin, I. (2010). Understanding and advancing the health of older populations in sub-Saharan Africa: policy perspectives and evidence needs. Public Health Reviews, 32(2), 357–376.

Adjei, N. K., Brand, T., & Zeeb, H. (2017). Gender inequality in self-reported health among the elderly in contemporary welfare countries: a cross-country analysis of time use activities, socioeconomic positions and family characteristics. PLoS One, 12(9), e0184676.

Ayernor, P. K. (2012). Diseases of ageing in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal, 46(2), 18–22.

Bauman, A., Phongsavan, P., Schoeppe, S., & Chey, T. (2010). Noncommunicable disease risk factors and socioeconomic inequalities–what are the links? A multicountry analysis of noncommunicable disease surveillance data. In World Health Organization (Ed.), Report to the WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Bradby, H. (2008). What works in tackling health inequalities? Pathways, policies and practice through the lifecourse-by Asthana, S. and Halliday. J. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30(5), 810.

Brinda, E. M., Attermann, J., Gerdtham, U. G., & Enemark, U. (2016). Socio-economic inequalities in health and health service use among older adults in India: Results from the WHO study on global AGEing and adult health survey. Public Health, 141, 32–41.

Cooke, E., Hague, S., & McKay, A., 2016. The Ghana poverty and inequality report: Using the 6th Ghana living standards survey. University of Sussex.

Debpuur, C., Welaga, P., Wak, G., & Hodgson, A. (2010). Self-reported health and functional limitations among older people in the Kassena-Nankana District, Ghana. Global Health Action, 3(1), 2151.

de-Graft Aikins, A. (2007). Ghana's neglected chronic disease epidemic: a developmental challenge. Ghana Medical Journal, 41(4), 154–159.

Eme Ichoku, H., Fonta, W., & Thiede, M. (2011). Socioeconomic gradients in self-rated health: a developing country case study of Enugu State, Nigeria. Economic Change and Restructuring, 44(3), 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-010-9098-.

Feng, Z., Wang, W. W., Jones, K., & Li, Y. (2012). An exploratory multilevel analysis of income, income inequality and self-rated health of the elderly in China. Social Science & Medicine, 75(12), 2481–2492.

Fernández, J. L., Forder, J., Trukeschitz, B., Rokosová, M., McDaid, D., & World Health Organization. (2009). How can European states design efficient, equitable and sustainable funding systems for long-term care for older people.

Fernandez-Martinez, B., Prieto-Flores, M. E., Forjaz, M. J., Fernandez-Mayoralas, G., Rojo-Perez, F., & Martinez-Martin, P. (2012). Self-perceived health status in older adults: regional and sociodemographic inequalities in Spain. Revista de Saúde Pública, 46(2), 310.

Fillenbaum, G. G., Blay, S. L., Pieper, C. F., King, K. E., Andreoli, S. B., & Gastal, F. L. (2013). The Association of Health and Income in the elderly: experience from a southern state of Brazil. PLoS One, 8(9), e73930.

Foebel, A. D., Pedersen, N. L., & Bravell, M. E. (2017). Self-rated health over time: the role of chronic disease, physical function and social networks. Innovation in Aging, 1(Suppl 1), 982.

Fonta, C. L., Nonvignon, J., Aikins, M., Nwosu, E., & Aryeetey, G. C. (2017). Predictors of self-reported health among the elderly in Ghana: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 171.

French, D. J., Browning, C., Kendig, H., Luszcz, M. A., Saito, Y., Sargent-Cox, K., & Anstey, K. J. (2012). A simple measure with complex determinants: investigation of the correlates of self-rated health in older men and women from three continents. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 649.

Ghana statistical service. (2010). Ghana's economic performance 2009 in figures.

Ghana Statistical Service (2013). 2010 Population and Housing Census: Summary Report of Final Results.

Goli, S., Singh, L., Jain, K., & Pou, L. M. (2014). Socioeconomic determinants of health inequalities among the older population in India: a decomposition analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29(4), 353–369.

Golini, N., & Egidi, V. (2016). The latent dimensions of poor self-rated health: how chronic diseases, functional and emotional dimensions interact influencing self-rated health in italian elderly. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 321–339.

Haley, W. E., Roth, D. L., Howard, G., & Safford, M. M. (2010). Caregiving strain and estimated risk for stroke and coronary heart disease among spouse caregivers differential effects by race and sex. Stroke, 41(2), 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.568279.

Hanibuchi, T., Nakaya, T., & Murata, C. (2010). Socio-economic status and self-rated health in East Asia: a comparison of China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. The European Journal of Public Health, 22(1), 47–52.

Haseen, F., Adhikari, R., & Soonthorndhada, K. (2010). Self-assessed health among Thai elderly. BMC Geriatrics, 10, 30.

Hosseinpoor, A. R., Bergen, N., Mendis, S., Harper, S., Verdes, E., et al. (2012). Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries: results from the world health survey. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 474.

Huijts, T., & Kraaykamp, G. (2011). Marital status, national marital status composition, and self-assessed health. European Societies, 13(2), 279–305.

Jehu-Appiah, C., Aryeetey, G., Spaan, E., de Hoop, T., Agyepong, I., & Baltussen, R. (2011). Equity aspects of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana: Who is enrolling, who is not and why? Social Science & Medicine, 72(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.025.

Jepsen, R., Dogisso, T. W., Dysvik, E., Andersen, J. R., & Natvig, G. K. (2014). A cross-sectional study of self-reported general health, lifestyle factors, and disease: the Hordaland health study. PeerJ, 2(2), e609.

Jylhä, M. (2009). What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine, 69(3), 307–316.

Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S., & Almeida-Filho, N. (2002). A glossary for health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56(9), 647–652.

Kunna, R., Sebastian, M. S., & Williams, J. S. (2017). Measurement and decomposition of socioeconomic inequality in single and multi-morbidity in older adults in China and Ghana: results from the WHO study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). International Journal for Equity in Health, 16, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0578-y.

Lloyd-Sherlock, P., Minicuci, N., Corso, B., Beard, J., Chatterji, S., & Ebrahim, S. (2017). Diseases of the rich? The social patterning of hypertension in six low-and middle-income countries. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(4), 827–842.

Maniecka-Bryla, I., Gajewska, O., Burzynska, M., & Bryla, M. (2013). Factors associated with self-rated health (SRH) of a University of the Third Age (U3A) class participants. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 57(2), 156–161.

Mba, C. J. (2010). Population ageing in Ghana: Research gaps and the way forward. Journal of Aging Research, 2010, 67–2157. https://doi.org/10.4061/2010/672157.

Molarius, A., Berglund, K., Eriksson, C., Lambe, M., Nordström, E., et al. (2007). Socioeconomic conditions, lifestyle factors, and self-rated health among men and women in Sweden. European Journal of Public Health, 17(2), 125–133.

Muchukuri, E., & Grenier, F. R. (2009). Social determinants of health and health inequities in Nakuru (Kenya). International Journal for Equity in Health, 8, 16–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-8-16.

Muntaner, C., Sridharan, S., Solar, O., & Benach, J. (2009). Against unjust global distribution of power and money: the report of the WHO commission on the social determinants of health: global inequality and the future of public health policy. Journal of Public Health Policy, 30(2), 163–175.

O’donnell, O., Van Doorslaer, E., Wagstaff, A., & Lindelow, M. (2008). Analyzing health equity using household survey data. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Phaswana-Mafuya N., Peltzer., K, Ramlagan S, Chirinda W, Kose, Z (2013). Social and health determinants of gender differences in disability amongst older adults in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid (Online), 18 (1), 1–9.

Rispel, L.C., Palha de Sousa, C.A.D., Molomo., B.G. (2009). Can social inclusion policies reduce health inequalities in sub-Saharan Africa?—A rapid policy appraisal. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 27(4), 492–504.

Sacker, A., Clarke, P., Wiggins, R. D., & Bartley, M. (2005). Social dynamics of health inequalities: a growth curve analysis of aging and self-assessed health in the British household panel survey 1991–2001. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(6), 495–501.

Saeed, B. I. I., Yawson, A. E., Agyei-Baffour, P., Nakua, É., & Ayesu, E. (2016). Effect of socio-economic factors in utilization of different healthcare services among older adult men and women in Ghana. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 390. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1661-6.

Santiago, L. M., de Oliveira Novaes, C., & Mattos, I. E. (2010). Self-rated health (SRH) as a predictor of mortality in elderly men living in a medium-size city in Brazil. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 51(3), e88–e93.

Shadmi, E., Balicer, R. D., Kinder, K., Abrams, C., & Weiner, J. P. (2011). Assessing socioeconomic health care utilization inequity in Israel: impact of alternative approaches to morbidity adjustment. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 609.

Solar, O., & Irwin, A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. In Social determinants of health discussion paper 2 (policy and practice). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Sozmen, K., & Belgin, U. N. (2014). Socioeconomic inequalities in non-communicable diseases and self-assessed health in Turkey. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 43(6), 736–748.

Sözmen, K., Baydur, H., Simsek, H., & Ünal, B. (2012). Decomposing socioeconomic inequalities in self assessed health in Turkey. International Journal for Equity in Health, 11, 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-73.

Stringhini, S., Forrester, T. E., Plange-Rhule, J., Lambert, E. V., Viswanathan, B., Riesen, W., Korte, W., Levitt, N., Tong, L., Dugas, L. R., Shoham, D., Durazo-Arvizu, R. A., Luke, A., & Bovet, P. (2016). The social patterning of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in five countries: Evidence from the modeling the epidemiologic transition study (METS). BMC Public Health, 16(1), 956.

Suzman, R. (2010). Guest editorial: the indepth WHO-SAGE multicentre study on ageing, health and well-being among people aged 50 years and over in eight countries in Africa and Asia. Global Health Action, 3. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v3403i3400.5480.

Szreter, S., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(4), 650–667.

World Health Organization. (2003). Dac guidelines and reference series poverty and health. OECD Publishing.

World Health Organization. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on social determinants of health final report. World Health Organization.

Wu, S., Wang, R., Zhao, Y., Ma, X., Wu, M., Yan, X., & He, J. (2013). The relationship between self-rated health and objective health status: a population-based study. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 320.

Yiengprugsawan, V., Lim, L. L., Carmichael, G. A., Sidorenko, A., & Sleigh, A. C. (2007). Measuring and decomposing inequity in self-reported morbidity and self-assessed health in Thailand. International Journal for Equity in Health, 6(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-6-23.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge WHO for making the data used in this study openly accessible online. We express gratitude to Mr. Nathaniel Boateng and Dr. Emmanuel Nwosu for valuable inputs and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CLF1*, GCA2 and JN2 developed the concept, planned the study and drafted the manuscript. MA2 planned and reviewed the manuscript. JN3 reviewed the manuscript and made valuable contributions. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not Applicable. This study used secondary analysis and data was publicly available online on request.

Consent for Publication

Not Applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fonta, C.L., Nonvignon, J., Aikins, M. et al. Economic Analysis of Health Inequality Among the Elderly in Ghana. Population Ageing 13, 113–127 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-019-09245-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-019-09245-7