Abstract

The goal of this paper is to analyze the equilibrium of the Italian market of white certificates (WC) during the 2006–2021 period by relying upon granular data of prices, traded volumes, demand, supply, and information on regulatory interventions. It emerges that market forces, represented by an infinitely inelastic demand curve and a convex supply function, describe the trends of prices and traded volumes up to mid-2016, while they do not during the following biennium. We suppose that the remarkable and sharp fluctuations of the WC price observed in 2016–2018 are due to decreasing returns that energy companies face in energy efficiency investments and to exogenous shocks caused by poorly designed regulatory interventions. It turns out that the equilibrium is the results of interactions between market forces and public intervention, as well as their related failures, aiming to a self-sustainable mechanism oriented to technological innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

EEOs schemes or WC can be expressed in terms of reduction of different units, for instance primary energy consumption in Italy, in final energy consumption in France, in carbon emission in UK.

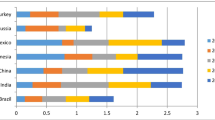

Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, UK. See Lees and Bayer (2016), Rosenow et al. (2017) for a detailed description of the architecture of EEOs schemes among these countries. In June 2018, the Danish government announced that the scheme will not be continued when it expires in 2021 (Surmeli-Anac et al. 2018).

See Fawcett et al. (2019).

“Additionality” refers to the certification of genuine and durable increases in the level of energy efficiency beyond what would have occurred in the absence of the energy efficiency measure, for instance only due to technical and market development trends and policies in place. The degree of additionality is a decisive factor in determining the economic viability of an energy efficiency project (Bertoldi et al., 2010; Stede 2017).

RVC-S are no longer among the feasible applications for new EE projects since 2017.

WC can be distinguished according to the sector where ES are attained: (i) electricity, Type-I, (ii) natural gas, Type-II, (iii) other than electricity and natural gas, but not in the transport sector, Type-III, (iv) other than electricity and natural gas, and attained in the transport sector, Type-IV.

Up to 2015, the minimum target was set to 50%.

The compliance period is from 1 June to 31 May, but since 2017 targets can also be attained by 30 November.

In 2017, MiSE set the 30 November as additional deadline for target compliance (Mise 2017).

It is worth to mention that since September 2017, the exchange of WC occurs on a unified basis, implying there is no more distinction, at least from the economic point of view, among the different types of certificates (Mise 2017).

For the sake of clarity, the supply/demand ratio is a macro indicator computed at a national level that is not able to take into account the possible excess of WC for a specific obligated party in the case of a national under-issuance to fulfill the early obligation.

As an alternative, the demand curve could be depicted as a very inelastic downward sloping curve implying that if energy companies fail to achieve energy-saving targets they will face a very high price of compliance, which may include the cost of the sanction imposed by regulators.

Just think about an energy company at its early stage of energy efficiency measures, as the implementation of fluorescent lamp that provide the company large savings at small costs, and a company that, in order to generate additional savings, must carry out further, and costly, renewable energy interventions such as co-generation or photo-voltaic plants.

Energy companies would not have any incentive in reducing energy consumption without an energy efficiency scheme.

Between 2011 and 2012 yearly supply increased by 72% while demand showed small increases.

Given that firms are facing increasing average and marginal costs, it is reasonable to suppose that they are not able to lower their minimum reservation price, denoted by the horizontal segment of the supply curve.

The calculation of the tau coefficient is given by the following formula:

$$\tau =\frac{RNI}{RNc}=\frac{{\sum }_{i=0}^{T-1}{(1-{\delta }_{i})}^{i}}{U}=1+\frac{RNa}{RNc}=1+\frac{{\sum }_{i=U}^{T-1}{(1-{\delta }_{i})}^{i}}{U}$$where RNI are net energy savings (i.e. gross energy savings minus non-additional energy savings), RNc are net energy savings expected during the useful lifetime, RNa are net energy savings between the end of useful lifetime and the end of technical lifetime, T is technical lifetime of the EE project (years), U is useful lifetime of the EE project (years), δ is the rate of decay of energy savings generated. The rationale behind the calculations of “k” coefficients (see Table 3) is the same of the tau coefficient except for that k allows to increase the amount of WC awarded by a higher amount during the first half of the project lifetime.

Stede (2017).

GSE (2014) reports a remarkable shift of projects from the residential and tertiary sectors to industry.

Many cases of fraud and irregularities on application procedures also emerged, leading to a lot of rejections of project proposals by GSE and ENEA (Mise 2018).

The margin between the price of WC and the new monetary reimbursement became 4 euro/toe, rather than 2 euro/toe as previously imposed (AEEGSI 2017a,b). It is worth to mention that the large demand of WC coupled with the difficulty of generating new certificates may have produced a hoarding effect among market participants, since those energy companies with a surplus of WC could have preferred to store them instead of selling in the market.

See AEEGSI (2017a).

“Traders” are obligated energy companies that have already achieved the compliance target or voluntary companies that trade WC in order to feed the upward trend of price and thus obtaining a capital gain or benefit from an higher monetary reimbursement.

The provisional value of the involved certificates was 700 million euros, of which 105 million already obtained and delivered to Eastern Europe countries and United Arab Emirates through a series of linked companies (Di Santo et al., 2018a,b, Di Santo et al. 2019). See also Guardia di Finanza: www.gdf.gov.it/stampa/ultime-notizie/anno-2017/ottobre/truffa-ai-danni-dello-stato-e-riciclaggio.-profitti-illeciti-per-105-milioni-di-euro. Similar issues have also emerged in France (Di Santo et al., 2018b). Most frauds dealt with the civil/household sector, since it is easier to find ways to produce false documents and data than with the industrial sector (Di Santo et al., 2018b).

For instance, strong regulatory instability and regulator interventionism have characterized the French WC scheme. See Tordjman et al. (2020).

Abbreviations

- AEEGSI:

-

Italian Energy Market Regulator

- EE:

-

Energy Efficiency

- EEOs:

-

Energy Efficiency Obligations

- ENEA:

-

Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy, and Sustainable Economic Development

- ES:

-

Energy Savings

- ESCOs:

-

Energy Service Companies

- IPEX:

-

Italian Power Exchange

- GME:

-

Italian Energy Markets Operator

- GSE:

-

Italian Energy Services Operator

- MiSE:

-

Italian Ministry of Economic Development

- MET:

-

Minister of Ecological Transition

- RSE:

-

Italian Research on the Energy System

- RVC:

-

Requests of certification

- Toe:

-

Tonne of oil equivalent

- Mtoe:

-

Millions of toe

- WC:

-

White Certificate/s

References

Agenzia nazionale per le nuove tecnologie, l'energia e lo sviluppo economico sostenibile (ENEA). (2014). Ottenere i titoli di efficienza energetica - Guida operativa 3.1.

Agenzia nazionale per le nuove tecnologie, l'energia e lo sviluppo economico sostenibile (ENEA). (2017). Rapporto Annuale Efficienza Energetica.

Agenzia nazionale per le nuove tecnologie, l'energia e lo sviluppo economico sostenibile (ENEA). (2020). Rapporto Annuale Efficienza Energetica.

Autorità di regolazione per energia reti e ambiente (AEEGSI) (2014). Deliberazione 23 Gennaio, 13/2014/R/efr

Autorità di regolazione per energia reti e ambiente (AEEGSI) (2016). Deliberazione 1 Dicembre, 710/2016/E/efr

Autorità di regolazione per energia reti e ambiente (AEEGSI) (2017b). Deliberazione 15 Giugno, 435/2017/R/efr.

Autorità di regolazione per energia reti e ambiente (AEEGSI) (2017a). Resoconto dell’indagine conoscitiva relativa all’andamento del mercato dei titoli di efficienza energetica (certificati bianchi), 28 Aprile.

Bertoldi P. and Rezessy S. (2006). Tradable Certificates for Energy Savings (White Certificates) - Theory and Practice. EUR 22196 EN. Luxembourg (Luxembourg): Publications Office of the European Union; 2006. JRC32865.

Bertoldi, P., Castellazzi, L., Spyridaki, N.A., Oikonomou, V., Renders, N., Moorkens, I., Fawcett, T. (2015). How is Article 7 of the Energy Efficiency Directive being implemented? An analysis of national energy efficiency obligation schemes. In: Eceee 2015 Summer Study Proceedings - First Fuel Now, pp. 455-465.

Bertoldi, P., Rezessy, S., Lees, E., Baudry, P., Jeandel, A., & Labanca, N. (2010). Energy supplier obligations and white certificate schemes: Comparative analysis of experiences in the European Union. Energy Policy, 38(3), 1455–1469.

Broc, J. S., Osso, D., Baudry, P., Adnot, J., Bodineau, L., & Bourges, B. (2011). Consistency of the French white certificates evaluation system with the framework proposed for the European energy services. Energy Efficiency, 4(3), 371–392.

Bye, T., & Bruvoll, A. (2008). Multiple instruments to change energy behaviour: The emperor’s new clothes? Energy Efficiency, 1(4), 373–386.

Child, R., Langniss, O., Klink, J., & Gaudioso, D. (2008). Interactions of white certificates with other policy instruments in Europe. Energy Efficiency, 1, 283–295.

Contaldi, M., Gracceva, F., & Tosato, G. (2007). Evaluation of green-certificates policies using the MARKAL-MACRO-Italy model. Energy Policy, 35(2), 797–808.

European Commission (EC) (2012). Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on energy efficiency, amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC, 14.11.2012, p. 1–56.

Di Santo, D., Biele, E., DAmbrosio, S., Forni, D., Tomassetti, G. (2014). Italian white certificates scheme: the shift toward industry. In: ECEEE Summer Study-Retool for a competitive andsustainable industry. Arnhem, The Netherlands, pp. 19–30.

Di Santo, D. (2017). Di Santo, D. 2017. Il meccanismo dei TEE: funzionamento, mercato e osservazioni. In: Atti convegno “Certificati bianchi: come sfruttare le nuove linee guida”. Federazione Italiana per l'uso Razionale dell'Energia. Convegno FIRE Key Energy, November 9.

Di Santo, D., De Chicchis, L., Biele, E., (2018a). White certificates in Italy: lessons learnt over 12 years of evaluation. In: International Energy Policy & Programme Evaluation Conference Proceedings.

Di Santo, D., E. Biele, and L. De Chicchis. (2018b). White certificates as a tool to promote energy efficiency in industry. Proceedings of the Eceee Summer Studies, Industrial Efficiency.

Di Santo, D., De Chicchis, L. (2019). White certificates in Italy: will it overcome the huge challenges it has been facing in the last three years?. In ECEEE 2019 Proceedings.

Duzgun, B., & Komurgoz, G. (2014). Turkey’s energy efficiency assessment: White Certificates Systems and their applicability in Turkey. Energy Policy, 65, 465–474.

Energy and Strategy Group (2017). Energy Efficiency Report. Politecnico di Milano.

Energy and Strategy Group (2019). Le Sfide dello Smart Manifacturing per ESCO e Utilities. Energy Efficiency Report. Politecnico di Milano.

Energy Union Package (2015). A framework strategy for a resilient energy union with a forwardlooking climate change policy. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank, COM, 80.

European Commission (EC) (2016). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency, 30.11.2016.

Eurostat,. (2017). Energy, transport and environment indicators (2017th ed.). Publications Office of the European Union.

Farinelli, U., Johansson, T. B., McCormick, K., Mundaca, L., Oikonomou, V., Örtenvik, M., & Santi, F. (2005). “White and Green”: Comparison of market-based instruments to promote energy efficiency. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13(10–11), 1015–1026.

Fawcett, T., Rosenow, J., & Bertoldi, P. (2019). Energy efficiency obligation schemes: Their future in the EU. Energy Efficiency, 12(1), 57–71.

Garbellini P. (2017). Analisi sul mercato dei titoli di efficienza energetica (TEE). Federazione Italiana Produttori di Energia da Fonti Rinnovabili (FIPER), Documento tecnico di supporto, 10 Febbraio.

Giraudet, L. G., and Finon, D. (2015). European experiences with white certificate obligations: A critical review of existing evaluations. Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy, 4(1), 113-130.

Giraudet, L. G., Bodineau, L., & Finon, D. (2012). The costs and benefits of white certificates schemes. Energy Efficiency, 5(2), 179–199.

Gestore dei mercati energetici (GME). (2012). Rapporto semestrale, 17 Luglio.

Gestore dei servizi energetici (GSE). (2014). Rapporto Annuale Certificati Bianchi 2013.

Gestore dei servizi energetici (GSE). (2018). Rapporto Annuale Certificati Bianchi 2017.

Gestore dei servizi energetici (GSE). (2019). Rapporto Annuale Certificati Bianchi 2018.

Gestore dei servizi energetici (GSE). (2020). Rapporto Annuale Certificati Bianchi 2019.

Gestore dei servizi energetici (GSE). (2021). Rapporto Annuale Certificati Bianchi 2020.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2012). Progress Implementing the IEA 25 Energy Efficiency Policy Recommendations. OECD-IEA Publishing.

Langniss, O., & Praetorius, B. (2006). How much market do market-based instruments create? An analysis for the case of white certificate. Energy Policy, 34, 200–211.

Lees, E., & Bayer, E. (2016). Toolkit for energy efficiency obligations. Regulatory Assistance Project.

Meran, G., & Wittmann, N. (2012). Green, brown, and now white certificates: Are three one too many? A micro-model of market interaction. Environmental and Resource Economics, 53(4), 507–532.

Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (MET). (2021). Ministerial Decree 21 May.

Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (MiSE). (2012). Ministerial Decree 28 December.

Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (MiSE). (2017). Ministerial Decree 11 January.

Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (MiSE). (2018). Ministerial Decree 10 May.

Mundaca, L., & Neij, L. (2009). A multi-criteria evaluation framework for tradable white certificate schemes. Energy Policy, 37, 4557–4573.

Oikonomou, V. (2010). Interactions of white certificates for energy efficiency and other energy and climate policy instruments. University of Groningen.

Oikonomou, V., & Jepma, C. J. (2008). A framework on interactions of climate and energy policy instruments. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 13(2), 131–156.

Oikonomou, V., Rietbergen, M., & Patel, M. (2007). An ex-ante evaluation of a White Certificates scheme in The Netherlands: A case study for the household sector. Energy Policy, 35(2), 1147–1163.

Pagliano, L., Alari, P., Ruggieri, G. (2003). The Italian energy saving obligation to gas and electricity distribution companies. ECEEE Summer Study: Mandelieu, 1059–1068.

Pavan, M. (2008). Tradable energy efficiency certificates: The Italian experience. Energy Efficiency, 1, 257–266.

Pavan, M. (2012). Tradable white certificates: Experiences and perspectives. Energy Efficiency, 5(1), 83–85.

Rosenow, J., Cowart, R., Thomas, S., Kreuzer, F. (2017). Costs and benefits of Energy Efficiency Obligations: A review of European programmes. Energy Policy, 107, 53-62.

Rosenow, J., & Bayer, E. (2017). Costs and benefits of Energy Efficiency Obligations: A review of European programmes. Energy Policy, 107, 53–62.

Sicard F., Escudero M. (2012). White certificates in France: the difficulty to standardize energy savings from an energy efficiency action – illustration through the micro modulating burner case. ECEEE 2012 Summer study on energy efficiency in industry Proceedings.

Sorrell, S., Harrison, D., Radov, D., Klevnas, P., & Foss, A. (2009). White certificate schemes: Economic analysis and interactions with the EU ETS. Energy Policy, 37(1), 29–42.

Stede, J. (2017). Bridging the industrial energy efficiency gap - Assessing the evidence from the Italian white certificate scheme. Energy Policy, 104, 112–123.

Surmeli-Anac, N., Kotin-Förster, S., & Schäfer, M. (2018). Energy Efficiency Obligation Scheme in Denmark Fact Sheet. Berlin (Germany): Ecofys und adelphi

Tordjman, F., Alexandre, S., Huneau, D., Pelosse, H., Anne-Braun, J., Crevoisier, L. de, Heim, G., Dambrine, F., Louviau, P. (2020). La cinquième période du dispositif des cerificats d'économies d'énergie (CEE) [The fifth period of the energy saving certificate scheme], Conseil Général de l'Environnement et du Développement Durable, Inspection Générale des Finances, Conseil Général de l'Economie, de l'Industrie, de l'Energie et des Technologies, November, 471p.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morganti, P., Garofalo, G. Interactions between market forces and regulatory interventions in the Italian market of white certificates. Energy Efficiency 15, 18 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-022-10027-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-022-10027-y