Abstract

This paper discusses potential new metrics for criticality assessments testing them on lithium supply chain. In the midst of the US-China technological competition, it is essential to fine-tune the methodology according to the new international context. First, to understand more in depth the structure and complexity of critical minerals supply chain, as countries are not fully aware of the intricate webs of cross-ownership or firm-to-firm relations that determine ultimate control from mining to downstream activities. To this end, I propose and discuss the concept of source of control (SOC). Second, I take as a case study the geography of production of lithium, from a country and company perspective, to show the complexity of two-level interconnections among entities involved. Criticality is a social-constructed feature that can inform policymaking in raw materials’ supply chains and it should consider not only where those critical minerals come from but also who controls their production. In order to test the plausibility of these improvements, I show how the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is intended to redraw the lithium-ion battery supply chain through a top-down approach. Generally, criticality studies have been primarily concerned about dependency risks while not considering the role of positive/negative externalities. Once these are clearly recognized, policy interventions should be tailored according to supply chain dynamics in industries or technological assets that States judge to be strategic.

Source: European Commission (2017)

Source: Author’s elaboration

Source: USGS (2023)

Source: Benchmark Minerals Intelligence, Wood Mackenzie

Source: United States Geological Survey (USGS)

Source: USGS, BGS

Source: RFC Ambrian

Source: Author’s own compilation. The flow is only indicative and not comprehensive

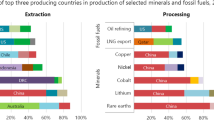

Source: DERA (2023), with 2021 data

Source: SNE Research

Source: Jones B., et al. (2021)

Source: American Enterprise Institute (AEI), China Global Investment Tracker

Source: USGS, BGS (2022)

Source: Company data, Wood Mackenzie, own research

Source: Company data, own research

Source: RFC Ambrian research (2023)

Source: own research based on corporate announcements and companies’ reports

Source: Company presentation

Source: own analysis based on corporate announcements and specialized media coverage (Argus, SMM, BMI)

Source: Ding and Dafoe (2021). The diagram is theoretically inside a two-way matrix, where the x-axis represents the economic or military utility of the given asset and the y-axis represents the economic or security externalities associated with the asset taking into account the level of supply chain integration (from upstream to downstream). The diagonal line consists of the nationalization of the asset

Source: S&P (2023)

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Not applicable.

Notes

This indicator describes the market concentration. The sum of squares is calculated for all involved shares (in percent). Thus, the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) can have values from 0 to 10,000. There are three categories for concentration: 0 to < 1500 low, 1500 to < 2500 moderate and over 2,500 high. This market concentration indicator goes back to Albert O. Hirschman (1945) and Orrin Herfindahl (1950).

The HHI used to calculate supply risks indicators is nonetheless useful because even foreign-owned mining companies or projects targeting specific raw materials are subject to inherently risks that are associated with a country or territory, for example political instability or climate risks (floods, droughts etc.).

Generally, institutional or individual investors need to ascertain two things in supply chain before deciding to make an investment decision: if the company has secured feedstock and guaranteed off-take agreements.

The network analysis is also useful for understanding the security implications of interdependence from a country perspective, where nodes in global production network can be weaponized or leveraged by entities (states) for coercive ends or by denying network access to adversaries as found by Newman & Farrel et al. (2019). See Section 3 of this manuscript.

The notions of “reshoring,” “nearshoring,” and “friendshoring” conceptualize the value of geographic proximity in intra-firm relationships. The problem is that, by incentivizing the come-back of mining, refining or manufacturing activities (prioritizing stages in the supply chain) it may not necessarily attract complex networks. For instance, the conflicting interests between producing and consuming countries can be seen in the different value added activities pursued within the supply chain: on the one hand, industrialized countries view the vulnerabilities and security of raw material supplies with increasing concern; on the other hand, non-OECD resource-rich countries look at the opportunity to build domestically downstream industry.

This has not to be confused with “vertical integration” which underline the level of integration of a single firm between upstream and downstream stages within its business structure. The horizontal dimension is thus related to B2C or B2B interactions taking into account the relative position of the ipothetical firm Y (operating company) and firm X (SOC).

As defined by Yeung and Coe (2015, 49), strategic partnership refer to “collaboration, coevolution, and joint development of a lead firms and its strategic partner(s) or key suppliers in the same global production network” with OEMs that often rely on established and trusted suppliers for specialized materials or products.

A clear example of this dynamic is the case of MP Materials, the only established rare earth producer in the USA. After going bankrupt in 2017, an investor consortium bought the Mountain Pass deposit from the former owner, Molycorp. Among of its shareholder, the Chinese mining company Shenghe Resources to which MP send rare earth concentrates (mostrly cerium and lantanum, with low amounts of NdPr) for further processing in China. While holding about 7.72% shares but not being the ultimate SOCs, the midstream position of Shenghe as a rare earth integrated producer (metal processing) further cement its bargaining and market power.

The relative increase in demand for lithium is due largely to a much smaller basis of comparison than for other minerals, because the current size of its market is smaller. Lithium demand in 2020 was roughly 300,000 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE), whereas the demand for refined copper was 75 times greater at 22,550,000 t, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

In the battery’s bill of materials, some components matter more than other: for a nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) cell, the cathode can make up to approximately 60% of its value, whereas the anode between 10 and 15%. Therefore, securing capacity for the cathode’s manufacturing, along with the production of precursor materials, are crucial for capturing the benefits of battery cell value-added stages.

Hard-rock and brine-based operations present different set of challenges related to technical and economic viability, costs and preference of downstream manufacturers. The close commercial relationship between chemicals providers and cathode/battery producers explain in parts why the lithium-ion battery network has been developed accordingly. See “The company perspective on global lithium production” section.

Data collected from these authors, relying on the Global Trade Tracker database, proved to be one of the most complete and detailed breakdown of lithium production, consumption and trading figures publicly available.

In contrast with lithium carbonate (HS 2836.91), breaking down lithium oxide and hydroxide trading figures is not possibile because they are subsumed under one HS commodity code (it is plausable that the latter accounts for the larger share).

Notable it was the Rio Tinto’s USD$ 850 million acquisition of the Rincon Lithium Project from Sentient Equity Partners.

Investors with interest for mining remain concentrated in Australia and Canada on their respective stock exchanges. The London Metal Exchange remains predominanlty a financial platform for trading spot and futures contracts on a range of non-ferrous metals and iron ore, but in 2012 it came under the control of Chinese capital: bought by the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

The choice to focus on headquarters (HQ) of companies rather than on location of operating or emerging projects is consistent with the methodology shown in the previous chapter, with a preliminar study on the country of incorporation to understand the relation between ownership and control.

It refers to the expansion of business activities within a company’s own supply chain. It may vary by scope of expansion (majority or minority shareholding stakes), means of expansion (founding or acquisition) and direction of expansion (upstream or downstream). Mining, processing and recylcing companies are relevant targets for vertical integration. However, according to DERA’s survey on raw materials strategy used by manufacturers, vertical integration is the least used amond the companies surveyed. This is mainly due to (a) large capital investments required; (b) loss of flexibility; (c) the complexity to manage different business models; d) reputational and economic risks.

Offtake agreements can be divided in “binding” or “not binding.” The former is realized when two commercial parties are bound to sell and pay for a certain amout of the material in a certain period of time; the latter is like a ‘promise’ that the price will be favourable and the quality of the material will be right. Companies commonly agree on a combination of the two through equity injections, meaning that the buyer company (investor) will invest in the mining operator with, for example, taking a 10% of equity. This operation is favorable for junior miners because in this way they can secure investment for developing the mine, but then the investor (being also the battery manufacturer) want its fair right to get the material. In brief, with offtake agreements companies become preferial buyers for these materials, and then of course they have return on investment (ROI) in form of capital other than securing the access to the material itself for their core business. Source: Personal conversation with market expert Lukasz Bednarski, author of Lithium (2021).

Looking at junior mining companies, there is an increasing trend toward business (vertical) integration. They typically approach the challenge by raising capital from investors for jump-start their mining activities, but they also tend to integrate mining operations with a refining plant, in order to generate more value for their shareholders. This trend is also interesting in the sense that build-up a mining site is matching the value of refining facilities, so their overall business counts on 1 billion dollars. Therefore, they don’t want to invest in a single stage, seeking all the capital required at once. They prefer, instead, to raise capital at two stages: mine development and then, if the project reach commercial feasibilty and show profitability, they may target the refinery investment. Source: Interview with market expert.

The chlor-alkali electrolysis process is used in the manufacturing of chlorine, hydrogen, and sodium hydroxide (caustic) solution. Of these three, the primary product is chlorine. Chlorine is one of the more abundant chemicals produced by industry and has a wide variety of industrial uses. Chlorine was first used to produce bleaching agents for the textile and paper industries and for general cleaning and disinfecting. Since 1950, chlorine has become increasingly important as a raw material for synthetic organic chemistry.

Interview with market expert.

See note 18 here at pag 28.

The Pampa Group corresponds to three shareholders that together own the majority of the shares in SQM and constitutes its SOC. From the GPN firm perspective, the shares held by the Pampa Group may not be sufficient to determine control on SQM business developments.

See here pag. 8 on “strategic value.”.

The existence of free trade agreements (which low trade restrictions scores in EU methodology) is rather a derisking factor in supply risk assessment, but is not a criteria conceived to categorize binarily between “allied” or “unfriendly” or “rival.”.

For example, the International Monetary Fund estimates that a 10% price shock will result in a 16.9% growth of lithium supply in the same year. After 20 years, the same price shock yields a supply growth of 25.5% (Boer et al. 2021).

Dependency on today lithium mining producers will decrease ten years from now. However, its criticality will likely not decrease substantially due to huge demand for decarbonization and eletrification worldwide, and because different battery grade lithium supplies will still be required to sastisfy industrial end-user. Source: Interview with market expert.

At the same time, except for Atacama in Chile and Olaroz in Argentina, most of the lithium projects in South America are still under development. It is likely that Australian-based operations will affect lithium mineral output in the short-mid term, thus making the Sino-Australian relation essential for market balance.

Covered countries by the US law are: China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia.

References

Abraham DS (2015) The elements of power. Gadgets, guns, and the struggle for a sustainable future in the rare metal age. Yale University Press, New Haven

Adamas Intelligence (2022) State of charge: EVs, batteries and battery materials, 7th biannual Report

Albemarle Corporation (2022) Albemarle Investor Presentation, Dec. 2022. https://s201.q4cdn.com/960975307/files/doc_presentations/2022/11/2022_12-(Dec)-Investor-Presentation-ALB_Web.pdf

Alliance for Automotive Innovation (2021) “Driving the U.S. economy,” Webpage. https://www.autosinnovate.org/initiatives/the-industry

Australian Government (2022) Resources and energy quarterly, December 2022. https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-12/resources-and-energy-quarterly-december-2022.pdf

Aresu A (2022) Il dominio del XXI secolo. Cina, Stati Uniti e la guerra invisibile sulla tecnologia, Milano, Feltrinelli

Aresu A, Prina Cerai A (2023) “BYD et CAT: dans la tête des Prométhées chinois de l’électricité” Le Grand Continent, August 30. https://legrandcontinent.eu/fr/2023/08/30/byd-et-catl-dans-la-tete-des-promethees-chinois-de-lelectricite/

Australian Government (2023) Australian Foreign Investment Policy, accessed 23 July 2023

Ayuk ET, et al (2020) Mineral resource governance in the 21st century: gearing extractive industries to sustainable development, UNEP, Nairobi, Kenya, https://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/mineral-resourcegovernance-21st-century

Azevedo M et al (2018) “Lithium and cobalt – a tale of two commodities”, McKinsey&Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/metals%20and%20mining/our%20insights/lithium%20and%20cobalt%20a%20tale%20of%20two%20commodities/lithium-and-cobalt-a-tale-of-twocommodities.pdf

Barandiaràn J (2019) Lithium and development imaginaries in Chile, Argentina and Bolivia. World Dev 113:381–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.09.019

Bastida EA (2020) The law and governance of mining and minerals: a global perspective. Hart Publishing, New York

Battery Materials Review (2023) 2022 Yearbook, February 2023. https://www.batterymaterialsreview.com/products/

Bedder MCJ (2020) The reconfiguration of the global supply chains of critical materials: behaviours and outcomes in the cobalt sector, PhD Dissertation, Cambridge University

Bednarski L (2021) Lithium. The global race for battery dominance and the new energy revolution, London, Hurst & Company

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (2019) “Lithium supply revisited” January 9, 2019. https://www.benchmarkminerals.com/blog-archive/lithium-supply-revisited/

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (2023) “Japan’s role in developing the lithium ion battery industry”, August 24th, 2023. https://source.benchmarkminerals.com/article/japans-role-in-developing-the-lithium-ion-battery-industry#:~:text=Over%20the%20nineties%20and%202000s,%2Dcadmium%2C%20and%20lead%20acid

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (2023a) “What’s going on with lithium prices?” January 6, 2023. https://source.benchmarkminerals.com/article/whats-going-on-with-lithium-prices

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (2023b) “China set to dominate African lithium production this decade,” April 14, 2023. https://source.benchmarkminerals.com/article/china-set-to-dominate-african-lithium-production-thisdecade

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (2023c) “Lithium: the multi-billion dollar question.” Webinar, March 2, 2023

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (2023d). “What’s going on with lithium prices?” January 6, 2023. https://source.benchmarkminerals.com/article/whats-going-on-with-lithium-prices

Berry C (2023) “The paradox of green growth: challenges and opportunities in decarbonizing the lithium-ion supply chain” In Kalantzakos S (ed), Critical Minerals, the Climate Crisis and the Tech Imperium, Amsterdam: Springer Edition, 2023

Blas J, Farchy J (2021) The world for sale. Money, power and the traders who barter the Earth’s resources, London, Penguin Random House

Blengini GA et al (2017) “EU methodology for critical raw materials assessment: Policy needs and proposed solutions for incremental improvements” Resource Policy, Vol. 53. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301420717300223

Boer L, Pescatori A, Stuermer M (2021) “Energy transition metals” IMF Working Paper 2021/243, October 12. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/10/12/Energy-Transition-Metals-465899

Buckley PJ, Clegg JL, Cross AR, Voss H, Rhodes M, Zheng P (2008) “Explaining China’s outward FDI: an institutional perspective” In Sauvant KP (ed) 1984. The rise of transnational corporations from emerging markets: threat or opportunity? Northampton, M.A: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited

Buijs B, Sievers H (2011) “Critical thinking about critical minerals: assessing risks related to resource security” POLINARES, Briefing Paper, EU FP7 Project

Bunting et al (2023) Resilient supply chains in the battery industry, Publication of the accompanying research on battery cell production on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action - II 2023. VDI/VDE Innovation + Technik GmbH, Berlin. https://www.ipcei-batteries.eu/fileadmin/Images/accompanying-research/publications/2023-03-BZF_Studie_Lieferketten-ENG.pdf

Bridge G (2008) Global production networks and the extractive sector. J Econ Geogr 8(3):389–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn009

Brown PC (2023) Industrial Policy for electric vehicle supply chains and the US-EU fight over the Inflation Reduction Act” PIIE Working Paper 23–1, May. Peterson Institute for International Economics

Capri A (2021) “The geopolitics of electric vehicles: techno-nationalism reshapes the automotive industry” Hinrich Foundation, November. https://www.hinrichfoundation.com/research/wp/tech/geopolitics-of-electric-vehicles/

Capri A (forthcoming) Techno-nationalism: How It’s Reshaping Trade, Geopolitics and Society, London, Wiley

International Energy Agency (2022a) “Critical minerals threaten a decades-long trend of cost declines for clean energy technologies”, accessed 18 May 2023, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/critical-minerals-threaten-a-decades-long-trend-of-cost-declines-for-clean-energy-technologies

International Energy Agency (2022b) Global EV Outlook 2022. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2022

International Energy Agency (2023a) Energy Technology Perspectives 2023. https://www.iea.org/reports/energytechnology-perspectives-2023

International Energy Agency (2023b) World Energy Investment, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2023

International Energy Agency (2023c) Critical minerals market review 2023, https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-market-review-2023

International Renewable Energy Agency (2023) Geopolitics of the Energy Transition: Critical Minerals, July 2023. https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Jul/Geopolitics-of-the-Energy-Transition-Critical-Materials

International Round Table on Materials Criticality (IRTC) (2020) “Business practice, material criticality: an overview for decision-makers”, May 2020, https://irtc.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/IRTC-Brochure-1.pdf

Jansson J (2013) “The Sicomines agreement revisited: prudent Chinese bank and risk-raking Chinese companies. Rev Afr Polit Econ 40:135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2013.762167

Javorcik SB, Kitzmueller L, Schweiger H, Yildirim AM (2023) “Economic costs of friend-shoring” CID Faculty Working Paper 422, September, Center for International Development, Harvard University

Jones B et al (2021) “Cadena de valor del litio: análisis de la cadena global de valor de las baterías de iones de litio para vehículos eléctricos”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2021/86), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/47108-cadena-valor-litio-analisis-la-cadena-global-valor-baterias-iones-litio

Johnston IA (2019) The failures of the ‘failure of engagement’ with China. Wash Q 42(2):99–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1626688

Kalantzakos S (2018) China and the geopolitics of rare earths. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kalantzakos S (2023) “Between rocks and hard places: geopolitics of net zero futures and the tech imperium” In Kalantzakos S (ed), Critical minerals, the climate crisis and the tech imperium, Amsterdam: Springer Edition, 2023

Keohane OR, Nye JS (2012) Power and interdependence, Fourth Edition, Longman. Kim, H., Coppola, G., “Chinese Firms Are Seeking Korean Partners to Skirt US EV Rules” Bloomberg, July 30. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-30/chinese-firms-are-seeking-korean-partners-to-skirt-us-ev-rules

King A (2021) Critical materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Kleimann D, Poitiers N, Sapir A, Tagliapietra S, Véron N, Veugelers R, Zettelmeyer J (2023) “Green tech race? The US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU Net Zero Industry Act” The World Economy, 00, August. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13469

Klier TH, Rubenstein JM (2022) “North America’s Rapidly Growing EV Market: Implications for the Geography of Automotive Production”, Chicago Fed Economic Perspectives, 5, December. https://doi.org/10.21033/ep-2022-5

Kolstad I, Wiig A (2009) What determines Chinese outward FDI? J World Bus 47:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2010.10.017

Koster H, Neubert FP, Dierksmeier K, Adelmann L, Lentge H, Schmidt P (2022) “Securing raw material supply: Benchmarking of measures of foreign manufacturing companies and recommendations for action”. – DERA Rohstoffinformationen, 52: 172 p., Berlin. https://www.deutsche-rohstoffagentur.de/DE/Gemeinsames/Produkte/Downloads/DERA_Rohstoffinformationen/rohstoffinformationen-52.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5

Kowalski P, Legendre C (2023) “Raw materials critical for the green transition: production, international trade and export restrictions”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 269, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c6bb598b-en

Ku AY, Loudis J, Duclos SJ (2018) “The impact of technological innovation on critical materials risk dynamics”

Krugman P (1995) Development, Geography and Economic Theory, The MIT Press, Cambridge

Lawder D (2023) US, Japan sign trade deal on electric vehicle battery minerals. Reuters. March 23, 2023, from https://www.reuters.com/business/autostransportation/us-japan-strike-trade-deal-electric-vehicle-battery-minerals-2023-03-28/

Lebrè E et al (2019) “Source risks as constraints to future metal supply”, Environmental Science & Technology, 53, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acs.est.9b02808

Leruth L et al (2022) “Green energy depends on critical minerals. Who control supply chains?” Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), Working Papers 22–12, August 2022, https://www.piie.com/publications/working-papers/green-energy-depends-critical-minerals-who-controls-supply-chains

Levy JS, Barbieri K (2004) “Trading with the enemy during wartime,” Security Studies 13, no. 3 (Spring 2004): 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636410490914059

Liberman P (1996) “Trading with the enemy: security and relative economic gains,” International Security 21, no. 1 (Summer 1996): 147–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539111

Lof A, Ericsson M (2019) Commodity trading - understanding the tax-related challenges for home and host countries, International Institute for Sustainable Development

Lorinc J (2022) “Canada orders three Chinese firms to divest from country’s lithium miners”, Bloomberg, 2 November 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-02/canada-orders-three-chinese-firms-to-divest-from-country-s-lithium-miners

Lorinc J (2023) “Lithium industry finally pulls off a multibillion-dollar deal” Bloomberg, 11 May 2023. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2023-05-11/lithium-industry-finally-pulls-off-mega-deal-with-livent-allkem-tie-up

Luo Y, Xue Q, Han B (2010) How emerging market governance promote outward FDI: experience from China. J World Bus 45:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.04.003

Luo Y, Van Assche A (2023) The rise of techno-geopolitical uncertainty: implications of the United States CHIPS and Science Act. J Int Bus Stud. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-023-00620-3

Mancheri AN (2015) World trade in rare earths, Chinese export restrictions and implications. Resour Policy 46:2

Mehdi A, Moerenhout T (2023) The IRA and the US Battery Supply Chain: Background and Key Drivers” June, Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia University. https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/publications/the-ira-and-the-us-battery-supply-chain-background-and-key-drivers/

Moran T (2010) China’s strategy to secure natural resources: risks, dangers and opportunities

Nassar TN, Alonso E, Brainard LJ (2020) “Investigation of U.S. foreign reliance on critical minerals—U.S. Geological Survey Technical Input Document in Response to Executive Order No. 13953 Signed September 30, 2020” (Ver. 1.1, December 7, 2020): U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2020–1127, 37 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20201127

NHK (2023) Top Japanese, US trade officials discuss EV tax breaks. NHK World-Japan. April 19, https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/20230420_04/

Miller C (2022) Chip war. The fight for the world’s most critical technology, Simon & Schuster, New York

OECD (2019) Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060 – Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequences. OECD Publishing, Paris

Patel-Campillo A (2010) Rival commodity chains: agency and regulation in the US and Colombian cut flower agro-industries. Rev Int Polit Econ 17(1):75–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290903296094

Peck D (2016) “A historical perspective of critical materials, 1939 to 2006” In Offerman, S. E., Critical materials. Underlying causes and sustainable mitigation strategies, World Scientific Series in Current Energy Issues, Vol. 5, World Scientific Publishing, Co., Singapore

Rietveld E, Bastein T, van Leeuwen T, Wieclawska S, Bonenkamp N, Peck D, Klebba M, Le Mouel M, Poitiers N (2022) Strengthening the security of supply of products containing Critical Raw Materials for the green transition and decarbonisation, publication for the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament, Luxembourg

Riofrancos T (2022) The security–sustainability nexus: lithium onshoring in the global north. Glob Environ Polit 23(1):20–41. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00668

SAFE (2020) The commanding heights of global transportation, September 15. https://secureenergy.org/the-commanding-heights-of-global-transportation/

Sanderson H (2022) Volt Rush. The Winners and Losers in the Race to Go Green. London: Oneworld Pubns Ltd

Sanderson H (2023) “Great Power Competition in the Lithium Triangle” in Bastina A.E., Graham D.J., Rupp A.J., Sanderson, H., (eds.) Latin America’s Lithium: Perspectives on Critical Minerals and the Global Energy Transition. Wilson Center. Sauvant K., and Chen V., (2014), “China’s regulatory framework for outward foreign direct investment” China Economic Journal, 7:1. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2013.874072

Schrijvers D, Hool A, Blengini GA, Chen W-Q, Dewulf J, Eggert R, … Wäger P (2020) A review of methods and data to determine raw material criticality. Resour Conserv Recycl 155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104617

Schrijvers D, Hool A, Blengini GA, Cimprich A, Chen W, Correia V, … Hool A (2020a) Material criticality: an overview for decision-makers. Retrieved March 5, 2023, from https://irtc.info/brochure/

Shanghai Metal Market (SMM) (2022) “China likely to enhance export restrictions on rare earth products and technologies”, https://news.metal.com/newscontent/102079383/china-likely-to-enhance-export-restrictions-on-rare-earth-products-and-technologies

Shanghai Metal Market (SMM) (2021) “Ganfeng lithium industry: plans to produce 100000 tons of LCE brine and clay lithium extraction capacity in 2025”, https://news.metal.com/newscontent/101471917/ganfeng-lithium-industry-plans-to-produce-100000-tons-of-lce-brine-and-clay-lithium-extraction-capacity-in-2025

Shepardson D (2023) “US House committees investigate Ford Chinese battery partnership”, Reuters, July 21. https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/us-house-committees-investigate-ford-catl-battery-partnership-2023-07-21/

Shim S (2011) “China’s rise and ‘Go-Out’ Policy”, POSRI China Quarterly, https://www.posri.re.kr/files/file_pdf/71/271/2825/71_271_2825_file_pdf_1457058703.pdf

Stott M (2022) “State looms over Latin America’s hopes to exploit ‘white gold’ of lithium”, Financial Times, 14 February 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/359d5287-d0ab-46ae-9c6b-09517ec9fb0c

Schmidt M (2023) “Raw Material Risk Assessment – Lithium”. DERA Rohstoffinformationen 54: 74 S., Berlin. https://www.bgr.bund.de/DE/Gemeinsames/Produkte/Downloads/DERA_Rohstoffinformationen/rohstoffinformationen-54-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3

Shen Y, Moomy R, Eggert GR (2020) China’s public policies toward rare earths 1975–2018. Min Econ 33:127

State Council (2011) 12th Five-Year Plan on Industrial Reform and Upgrading, Beijing: State Council

Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP) (2022) Mid-decade challenges to national competitiveness, September, https://www.scsp.ai/2022/09/special-competitive-studies-project-releases-first-report-sept-12-2022/

Standard & Poor (2023) Inflation Reduction Act: impact on North America metals and minerals market, Final Report, August. https://cdn.ihsmarkit.com/www/prot/pdf/0823/Impact-IRA-Metals-Minerals-Report-FINAL-August2023.pdf

Sustainable Materials and Technologies, Vol. 15. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214993717300489

Tegen A (1994) Western world gold industry: ownership and control. Raw Mater Rep 10(1):17–24

The Economist (2009) “China’s ‘going out’ strategy”, accessed 10 may 2023, https://www.economist.com/free-exchange/2009/07/21/chinas-going-out-strategy

The White House (2017) Executive order on a federal strategy to ensure secure and reliable supplies of critical minerals, 20 December. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/12/26/2017-27899/a-federal-strategy-to-ensure-secure-and-reliable-supplies-of-critical-minerals

The White House (2020) Executive Order on Addressing the Threat to the Domestic Supply Chain From Reliance on Critical Minerals From Foreign Adversaries and Supporting the Domestic Mining and Processing Industries, September 30. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/10/05/2020-22064/addressing-the-threat-to-the-domestic-supply-chain-from-reliance-on-critical-minerals-from-foreign

The White House (2021) Executive Order on America’s supply chains, 24 February. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefng-room/presidential-actions/2021/02/24/executiveorder-on-americas-supply-chains/

The White House (2022) Presidential Determination No. 2022–11 of March 31, 2022 Presidential Determination Pursuant to Section 303 of the Defense Production Act of 1950, as Amended. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-04-06/pdf/2022-07421.pdf

The White House (2023) Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Renewing American Economic Leadership at the Brookings Institution, Speeches & Remarks, April 27. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/04/27/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-on-renewing-american-economic-leadership-at-the-brookings-institution/

Turner MJ (2022) Charged. A history of batteries and lessons for a clean energy future, Washington: University of Washington Press

United Nations (2021) “Lithium-ion batteries: a pillar for a fossil fuel-free economy?” Economic Analysis, July 2021. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/FTI_July2021.pdf

UNECA (2021) Facts & Figures: on cobalt, battery minerals and electric cars value chains, UNECA, Addis Abeba https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/Africa-Business-Forum/4/Cobalt.pdf

US National Research Council (2008) Minerals, critical minerals, and the U.S. economy. Retrieved April 23, 2023, from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12034/minerals-criticalminerals-and-the-us-economy

US Department of Energy (2022) America’s strategy to secure the supply chain for a robust clean energy transition, February, https://www.energy.gov/policy/articles/americas-strategy-secure-supply-chain-robust-clean-energy-transition

US Department of Energy (2022a) “Biden-Harris Administration Awards $2.8 Billion to Supercharge U.S. Manufacturing of Batteries for Electric Vehicles and Electric Grid”, October 19. https://www.energy.gov/articles/biden-harris-administration-awards-28-billion-supercharge-us-manufacturing-batteries

US Department of Energy (2023) Critical Materials Assessment, July, https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2023-07/doe-critical-material-assessment_07312023.pdf

US Department of Defense (2022) Defense Production Act Title III Presidential Determination for Critical Materials in Large-Capacity Batteries, April 5

US Department of Treasury (2023) Anticipated direction of forthcoming proposed guidance on critical mineral and battery component value calculations for the new clean vehicle credit, accessed 25 July 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/30DWhite-Paper.pdf

van den Boogaart SDK (2015) “The development of the market for rare earth elements: Insights from the economic theory” Resource Policy, Vol. 46. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301420715001014

Van Evera A (1999) Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conflict. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Vivoda V (2023) “Friend-shoring and critical minerals: exploring the role of the minerals security partnership” Energy Research and Social Science, Vol. 100, June. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103085

Waltz K (1979) Theory of international politics. McGraw-Hill, New York

Wang P, Yu Z (2014) China’s outward foreign direct investment: the role of natural resources and technology. Econ Polit Stud 2:2. https://doi.org/10.1080/20954816.2014.11673846

World Bank (2011) Overview of state ownership in the global minerals industry. World Bank, Washington

World Bank (2020) Minerals for climate action: the mineral intensity of the clean energy transition. World Bank, Washington

World Economic Forum (WEF) (2023). Global Risk Report 2023. World Resources Forum. Retrieved May 23, 2023, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/global-risks-report-2023-experts-davos2023/

White House (2022a) Memorandum on Presidential Determination Pursuant to Section 303 of the Defense Production Act of 1950, as amended, accessed 24 July 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/03/31/memorandum-on-presidential-determination-pursuant-to-section-303-of-the-defense-production-act-of-1950-as-amended/

Yeung HW (2022) Explaining geographic shifts of chip making toward east asia and market dynamics in semiconductor global production networks. Econ Geogr 98(3):272–298

Yeung HW (2009) Regional development and the competitive dynamics of global production network: an East Asian perspective. Region Stud 43:3. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400902777059

Yeung HW (2021) Regional worlds: from related variety in regional diversification to strategic coupling in global production networks. Region Stud 55:6. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1857719

Zhang Y (2009) Unravelling the complex motivation behind China’s Outward FDI. J Asia-Pacific Econ 19:1. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2013.803843

Zimmermann A (2023) “Europe’s green dilemma: Mining key minerals without destroying nature”, Politico, https://www.politico.eu/article/europes-green-dilemma-mining-key-minerals-without-destroyingnature/

Zuo X (2021) “The Trump effect: China’s new thoughts on the United States”. The Washington Q 44 (1): 107–127. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0163660X.2021.1893515

Funding

The author declares that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Prina Cerai, A. Geography of control: a deep dive assessment on criticality and lithium supply chain. Miner Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-023-00414-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-023-00414-x