Abstract

The aim of this paper is to analyze the inclusion of Green Public Procurement (GPP) requirements in the EU public procurement regime. The debate about moving towards greener public purchasing has been fueled afresh in the wake of the EU Green Deal, which highlights the significance of a public procurement regime in pursuing the existing environmental policy goals at EU level. This is also reflected in other key EU policy documents, such as the Circular Economy Package, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well as the climate change legislation implementing the Paris Agreement. In this context, this paper aspires to map the intersections between the public spending decisions of contracting authorities and their discretion in inserting environmental considerations through the lens of increasing compliance with the adopted environmental targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Government expenditure on works, goods and services represent around 19% of EU GDP, accounting for roughly EUR 2.3 trillion annually.Footnote 1 Due to this massive value of public procurement, and the enormous market it creates, public procurement, particularly when used in a strategic way, is a relevant and powerful way to respond to societal, environmental and economic challenges, and to shape the way in which both the public and private sector behave on the market. Hence, nowadays, public procurement satisfies a variety of concerns relating to: a. anticorruption and transparency, b. efficiency (the best value for money), c. policy instruments, such as social and environmental considerations, d. competition concerns, e. building an internal market for government procurement in the EU context.Footnote 2

Generally, in developed as well as developing countries, a sound procurement system seems to have two groups of objectives: procurement and non-procurement.Footnote 3 Namely, the procurement objectives normally include quality, timeliness, cost (more than just price), minimizing business, financial and technical risks, maximizing competition and maintaining integrity, whilst the non-procurement objectives cover environmental protection priorities, social objectives and international relations (i.e. global trade agreements) objectives. At EU level, the debate about the interrelationship between the public procurement rules and the achievement of environmental goals at EU level has revived in the wake of the 2014 EU Public Procurement reform, where it was acknowledged that public procurement is a powerful tool of the competitiveness and sustainable growth agenda.Footnote 4 Therefore, no longer will the EU simply coordinate national procurement procedures to protect the integrity of the internal market in public contracts, but now it also seeks to deploy public procurement as a “demand-side policy” to achieve its own key economic goals.Footnote 5 In this context, the new Directive 2014/24/EU (hereafter: Public Procurement Directive) used the lever of public procurement to integrate strong social and environmental dimensions without, however, specifying the conditions under which these two fields will jointly serve their original purposes.

The emergence of the concept of Green Public Procurement (hereafter: GPP) is directly linked to the constantly increasing role of environmental protection in the EU policy priorities and targets since 1986 with the entry into force of the Single European Act (SEA). Namely, over the last two decades, environmental issues have been placed very high on the EU political agenda, given that the current situation of the environment worldwide is alarming for a combination of reasons. In order to face these challenges and strengthen the achievement of local, regional, national and EU environmental goals, the EU legislator has conceived the green shift in public purchasing leading to the adoption of several EU green public procurement framing measures, some of which are actually binding. In a broader conceptual framework, GPP is but one of sustainable public procurement (SPP)’s components,Footnote 6 which encompasses the three pillars of economic, social and environmental responsibility. This paper focuses on environmental considerations in the public procurement context rather than social and economic sustainability aspects.

According to the definition given by the Commission, GPP is “a process whereby public authorities seek to procure goods, services and works with reduced environmental impact through their life cycle when compared to goods, services and works with the same primary function that would otherwise be procured”.Footnote 7 In other words, GPP constitutes an important tool to promote the use of greener products and services by the public authorities and, therefore, to achieve environmental policy goals relating to climate change, biodiversity loss, resource efficiency and sustainable production and consumption. Indicatively, GPP can be instrumental in addressing environmental problems such as: deforestation (e.g. through the purchase of wood and wood products from legally harvested and sustainably managed forests), greenhouse gas emissions (e.g. through the purchase of products and services with a lower CO2 footprint through their life-cycle), waste (e.g. by specifying processes or packaging which generate less waste or encouraging reuse and recycling of materials), air, water and soil pollution (by controlling chemicals and limiting the use of hazardous substances).Footnote 8

Currently, GPP is still a voluntary instrument meaning that it is up to the Member States (hereafter: MS) and their contracting authorities to implement it. In this context, the EU GPP criteria sets developed by the European Commission for 20+ priority productsFootnote 9 are non-binding and not formally adopted as a legal act. In other words, the EU GPP criteria are a supporting framework, providing concrete clauses on how to “green” public purchasing of the targeted products, and setting a non-binding level of ambition as to what is considered a sufficient “effort” in greening the purchasing.Footnote 10

With respect to the role of the GPP as an environmental policy instrument, despite the fact that the Public Procurement Directive now permits GPP, its limited uptake demonstrates that it is still questionable to what extent the (social and environmental) compliance constraints that are not inherent to the act of buying are adequately deployed when shaping the buying decision. Consequently, the effectiveness of the relevant legislative provisions is called into question due to the discretion allocated to contracting authorities in inserting environmental consideration in their spending decisions.

In this context, this paper focuses on mapping the misbalance between the discretion assigned to contracting authorities within the existing voluntary GPP regime and the role of the public procurement as a mechanism to increase compliance of MS with environmental objectives. In general, the discussions about the role of the GPP as an environmental policy tool have been stepped up in the last decade, given that environmental concerns have become a fundamental part of EU law through the establishment of more than 130 separate environmental targets to be met between 2010 and 2050.Footnote 11 In this context, public procurement has explicitly emerged as a potentially effective toolkit in the hands of policy makers for achieving compliance with the adopted environmental objectives at EU law landscape. Hence, the main research focus revolves around the question of how to make the public procurement process more suitable to achieve compliance with the adopted environmental goals.

To this end, the second section focuses on the policy and legislative evolution of GPP at EU level, whereas the third section puts the spotlight on the GPP requirements under the current EU public procurement regime. In the fourth section, the role of the Public Procurement withing the EU environmental policy is identified, while in the fifth section emphasis is placed on analyzing the ways to elicit public procurement provisions compliance with environmental policy objectives exceeding the simple act of buying a good or a service. In the sixth and final sections some concluding remarks are briefly formulated.

2 Unpacking the GPP policy and legislative developments

Despite the fact that the relevance of GPP has grown significantly over the past years, it still constitutes a less explored and non-binding area. More specifically, in 1996 and 1998, the Commission started to give a certain importance to the environment in public tenders. Indeed, in 1996 it was the Green Paper “Public Procurement in the European Union: Exploring the way forward”Footnote 12 and in 1998 the White Paper “Public Procurement in the European Union”,Footnote 13 which provided an incentive to consider a variety of environmental considerations through a broader interpretation of the existing public procurement directives. Following these first documents, the European Commission developed various initiatives and policy documents to promote the concept of GPP.

Namely, in 2001 an “Interpretative communication of the Commission on the Community law applicable to public procurement and the possibilities for integrating environmental considerations into public procurement” was launched underlying the interlinkages between the scarcity of natural resources and the sustainable production and consumption as well as highlighting the use of public procurement to favour environmentally-friendly products and services.Footnote 14 Two years later, in 2003, the European Commission in its “Communication on Integrated Product Policy”Footnote 15 encouraged MS to sketch out publicly available National Action Plans (NAPs) to enhance GPP. The NAPs, which are not legally binding, should assess the existing situation as well as set ambiguous targets for the next three years, specifying which measures shall be taken to achieve them.

The most comprehensive policy document relating to the GPP published by the European Commission was the 2008 “Communication on Public procurement for a better environment” combined with a Commission Staff Working Document establishing specific (but indicative) green public procurement (GPP) targets.Footnote 16 Hence, EU GPP criteria have been set for more than 20 groups of products, while there is a constant production of reports and studies assessing the progress and the impact of this instrument. Although the existing voluntary EU GPP criteria offer guidance for particular types of products and services, the total uptake of GPP processes across the EU remains limited and fragmented with the top four performers having an uptake up to 60% and 12 MS having an uptake of less than 20%.Footnote 17

In addition to this, specific mandatory GPP rules have been sporadically inserted in various pieces of legislation. Namely, the Energy Star Regulation (2008), requiring the buying of energy efficient IT office equipment; the Clean Vehicles Directive (2009), mandating environmental friendly vehicles; the Energy Performance Buildings Directive (2010), introducing an obligation for new buildings owned and occupied by public authorities to be “nearly zero-energy” by end of 2018; and the Energy Efficiency Directive (2012), to purchase energy efficient buildings and equipment of the highest energy labelling class.

3 Mapping the GPP requirements in the current EU Public Procurement regime

In the wake of the well-known CJEU case law in this field,Footnote 18 the 2014 EU Public Procurement Reform led to the adoption of the Article 18(2), which explicitly recognizes that “MS shall take appropriate measures to ensure that in the performance of public contracts economic operators comply with applicable obligations in the fields of environmental, social and labour law established by Union law, national law, collective agreements or by the international environmental, social and labour law provisions listed in Annex \(\mbox{X}''\). Hence, the new Public Procurement Directive facilitates the integration of environmental considerations at various stages of the public procurement procedure including allowing for environmental requirements, the use of criteria underlying environmental labels, and the option to take into account environmental factors in the production process and life-cycle analysis.Footnote 19

More specifically, as regards the definition of the subject matter of the contract, the contracting authorities as buyers have a wide discretion and the Directive does not prevent them from implementing environmental considerations when deciding on a purchase.Footnote 20 However, limit to their discretionary power can be found in the Article 18(1) stipulating that “the design of the procurement shall not be made with the intention of excluding it from the scope of this Directive or of artificially narrowing competition”.

Furthermore, the technical specifications, which define the characteristics required of a work, service or supply according to Article 42 of the Directive, may be formulated in terms of performance or functional requirements including environmental aspects.Footnote 21 Indicatively, they may cover environmental and climate performance levels, production processes and methods at any stage of the life-cycle of works and packaging.Footnote 22 In the same vein, Article 43 spells out the conditions under which the contracting authorities may purchase works, supplies or services with specific environmental, social or other characteristics requiring – in the technical specifications, the award criteria or the contract performance conditions – a specific label as means of proof that the works, services or supplies at stake correspond to the required characteristics. Namely, the label requirements must concern only criteria which are linked to the subject-matter of the contract, and are based on non-discriminatory criteria which are objectively verifiable by the contracting authorities. Additionally, the labels must be established in an open and transparent procedure, accessible to all interested parties and set by a third party over which the economic operator cannot exercise a decisive influence.

With respect to the selection and award of contracts phase, there is scope for introducing environmental consideration. Namely, according to Article 56(2), contracting authorities may circumvent the general rule of awarding the contract based on the most economically advantageous tender (Article 67) “where they have established that the tender does not comply with the applicable obligations referred to in Article 18(2).” Hence, giving effect to this ambitious but optional provision by blocking a tenderer which is not taking into account environmental (and/or social) impacts of their tender, lies exclusively in the power of the contracting authorities and the MS. In addition to this, as regards environmental considerations, Article 57(4) of the Directive sets out non-binding grounds on which economic operators may be excluded from participation in a procurement procedure. It is again left to the contracting authorities to bring these voluntary exclusions for violation of environmental obligations to life. In the same vein, but this time based on a compulsory provision enshrined in Article 69(3), “contracting authorities shall reject the tender, where they have established that the tender is abnormally low because it does not comply with applicable obligations referred to in Article 18(2)”.

Moreover, as shown by Concordia and a number of subsequent cases, award criteria provide the most relevant opportunity for green public procurement.Footnote 23 Article 67 is therefore of paramount importance, since it gives MS the discretionary power to determine that contracting authorities may not use price only or cost only as the sole award criterion. This allows the contracting authorities to award a contract in line with the optimum price-quality ratio assessed on the basis of criteria which may include environmental considerations as well.Footnote 24 However, again this discretion is not unrestricted. According to Article 67(3)–(5) award criteria must: have a link to the subject-matter of the contract; be specifically and objectively quantifiable; have been advertised/notified previously; respect EU law and comply with the fundamental principles of equal treatment, non-discrimination and transparency.

An additional innovative element of great importance relating to the “greening” of the public procurement process is the codification of the life-cycle costing in Articles 67(2) and 68. In light of this concept, “the most economically advantageous tender from the point of view of the contracting authority shall be identified on the basis of the price or cost, using a cost-effectiveness approach, such as life-cycle costing” which “covers parts or all of the costs over the life cycle of a product, service or works” including “costs imputed to environmental externalities linked to the product, service or works during its life cycle, provided their monetary value can be determined and verified; such costs may include the cost of emissions of greenhouse gases and of other pollutant emissions and other climate change mitigation costs”.

Finally, in the contract performance stage, the Directive in Article 70 authorizes the contracting authorities to set out specific conditions relating to the performance of a contract, provided that they are linked to the subject matter of the contract, are not directly or directly discriminatory, and are indicated in the call for competition or in the procurement documents. According to this provision, contract performance conditions “may include economic, innovation-related, environmental, social or employment-related considerations” creating a potentially dynamic field to be enacted by the contracting authorities.

As highlighted in legal doctrine, from “secondary considerations” in the 2004 Directives, the need to include social and environmental considerations in public tendering procedures has resulted in coining new terms, much more powerful and all-encompassing, such as “horizontal policies”, “sustainable procurement” or even “strategic procurement”.Footnote 25 Following this reform, it has been left up to the MS to determine how and to what extent they may seek to achieve environmental goals through the public procurement requirements. Nevertheless, the practical enforcement of these provisions remains largely untapped so far.

4 Identifying the role of Public Procurement within the EU Environmental Policy Priorities

Having acknowledged the nexus between public procurement and environmental policy goals, this chapter unboxes the EU environmental policy framework underpinning the analysis which follows. It is about the latest policy and legislative developments in the field of environmental protection which constitute the driving forces in strengthening the role of public procurement as a regulatory compliance mechanism exceeding the simple act of buying a good or service.

4.1 Article 11 TFEU – principle of integration

Including environmental considerations in the procurement decisions is directly linked to the overall position of environmental protection in the European Union. Namely, since 1986 with the entry into force of the Single European Act (SEA) the European Economic Community had to take environmental protection requirements into account when designing other Community policies, mainly the economic and internal market policies. Today, this is enshrined in Article 11 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) setting out an all-encompassing legal duty to integrate environmental protection requirements in the policies and activities of the European Union. More specifically, Article 11 TFEU, which is known as the “environmental integration clause”, explicitly requires “environmental protection requirements to be integrated into the definition and implementation of the Union policies and activities, in particular with a view to promoting sustainable development”.

While at its roots, EU Environmental policy was meant to prevent diverse environmental standards resulting in trade barriers and competitive distortions in the internal market, today it plays a different, much more active and integrated role.Footnote 26 Thus, the principle of integration requires that legislation in other policy areas be modified or amended in its substantive content in order to meet environmental protection requirements, where necessary.Footnote 27 In other words, environmental policy integration attempts to act on the recognition that more can be achieved by incorporating environmental concerns within other policy areas (such as agriculture, energy, internal market, trade, fisheries, transport, industry, tourism, economic and financial affairs) than by leaving them to an explicitly “environmental policy”.Footnote 28 In this context, environmental integration is in part an effort to “shift from a traditional antagonistic model” of the relationship between different policy objectives and policy actors “to a new cooperative model”.Footnote 29

Although Article 11 TFEU stipulates that when shaping EU sectoral policies not only their particular concerns but also the environmental aspects must be taken into account, the impact of the integration principle is hardly apprehendedFootnote 30 and the precise obligations deriving from this Article remain vague.Footnote 31 Namely, it is, firstly, unclear what precisely falls within the scope of the “environmental protection requirements”. Certainly, it would seem to include the environmental policy objectives and principles enshrined in Article 191(1) and (2) TFEU. In addition to this, the environmental policy aspects referred to in Article 191(3) TFEU should not a priori be excluded, though it is true that the Treaty does not state that these aspects have to be taken into account.Footnote 32

Secondly, it is questionable whether the implementation of the principle of integration is interpreted broadly or narrowly.Footnote 33Jordan and Lenschow compared strong approaches to integration, in which priority is given to environmental objectives, with weaker approaches, which emphasize the search for win-win options and weigh the different objectives more evenly highlighting that the latter seems to be the approach taken in the EU.Footnote 34 Moreover, Advocate General Geelhoeld, for example, has rejected the proposition that Article 11 requires environmental protection to “always be taken to be the prevalent interest”, confirming instead its procedural (“take due account”) dimension.Footnote 35 In this respect, the integration principle at least legitimizes the relevance of environmental considerations to other areas of policy, and the Treaty’s mandatory language should create an obligation for decision-makers. Environmental protection may “form part of”Footnote 36 or even be “regarded as an objective of other areas of policy”.Footnote 37

4.2 EU Green Deal – overarching policy priorities

Confirmation of the continuous strengthening of the environmental integration obligation and its increased significance at policy level can be found in the recently adopted EU Green Deal,Footnote 38 which is the new EU growth strategy focusing on tackling climate and other pressing environmental-related challenges. Emphasis is given to the transition towards a climate-neutral Europe by 2050 based on the efficient use of resources by moving to a clean, circular economy, the restoration of biodiversity and the reduction of pollution. Without putting the spotlight on the detailed provisions and actions in different environmental areas, the adoption of the EU Green Deal triggers intensive discussions about the role of public procurement rules as a crucial mechanism in achieving the new and ambitious EU environmental goals.

Namely, according to the provisions of the EU Green Deal, “public authorities, including EU institutions, should lead by example and ensure that their procurement is green. The Commission will propose further legislation and guidance on green public purchasing”.Footnote 39 In addition to this, “the Commission will propose minimum mandatory green criteria or targets for public procurements in sectorial initiatives, EU funding or product-specific legislation. Such minimum criteria will “de facto” set a common definition of what a “green purchase” is, allowing collection of comparable data from public buyers, and setting the basis for assessing the impact of green public procurements. Public authorities across Europe will be encouraged to integrate green criteria and use labels in their procurements. The Commission will support these efforts with guidance, training activities and the dissemination of good practices”.Footnote 40 It is therefore evident that GPP may have a crucial role in the tool kit of the policy makers when developing policies that either affect environmental goods or aim to achieve the already adopted environmental objectives.

In general, the EU Green Deal aspires to function as the overarching umbrella coordinating comprehensively the developments in the field of environmental policy, which has been constantly evolving in order to deal effectively with the growing environmental problems such as climate change, biodiversity loss, soil degradation and water scarcity. As captured in the EU Green Deal, the new EU environmental objectives, which have been adopted in different policy areas, such as circular economy, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Climate Change and Decarbonization of Economy, sorely test the existing environmental policy tools. Hence, in order to achieve these ambitious and highly complicated environmental goals, “demand-side policies” such as the GPP can be useful tools.Footnote 41

4.3 Sustainable development goals

Since the adoption of the new Public Procurement Directive, it has become clear that governments’ key factor in determining public purchasers’ choices is no longer exclusively the cheapest option available but the integration of social and environmental dimensions in public procurement rules. Given the high impact of public procurement on a country’s economic development, the introduction of environmental and social sustainability principles in this process aims to achieve a number of social and environmental objectives. Based on that, the concept of sustainable public procurement has emerged, capturing the need to address sustainability issues through procurement. Sustainable public procurement builds on three decades of thinking on sustainable development, following the seminal World Commission on Environment and Development (the Brundtland Report) of 1987 and the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992 (Earth Summit).Footnote 42

At the beginning of 2015, the UN Sustainable Development Summit ended with the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which encompasses 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at its base. This Agenda is the most important international strategy on sustainability and it was subscribed to by 193 UN member countries during COP21 (Paris Agreement on Climate Change in December 2015).Footnote 43 GPP is enshrined in the SDG’s 12 “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” in a specific target: No. 12.7 focused on promoting public procurement practice that is sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities; No. 12.7.1 focused on the importance of implementation of sustainable public procurement policies and action plans by the countries. Hence, incorporating sustainability considerations into public procurement will assist governments in reducing CO2 emissions, protecting water and energy resources, alleviating poverty, equity and cohesion problems, and ultimately gaining technological innovations.Footnote 44

Given that the EU Green Deal is an integral part of the “Europe 2020” strategy to implement the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda and the sustainable development goals, achieving Sustainable Development constitutes an EU priority, which does not only legitimize but also necessitates further EU action on this matter.Footnote 45 Based on that, it is of paramount importance to discuss the ways procurement law and policy frameworks as well as actual government purchasing practices will be brought into alignment with the SDGs and the other EU Sustainable Development commitments.

4.4 EU Circular Economy Policy

In 2015 the EU decided to transform its linear economy (take-make-dispose) into a Circular Economy (CE)Footnote 46 aspiring to decouple economic growth and well-being from ever-increasing waste generation, strengthen environmentally sound waste management, enhance eco-design, achieve higher recycling rates and reduction of waste, stimulate competitiveness and resource-efficiency as well as create new jobs and opportunities for new businesses, innovations and investments by keeping the added value in products for as long as possible in the market. The CE policy pointed out in a holistic way the interrelation among resource, substance, product and waste highlighting the interface among the waste, product and chemical legislations taking into consideration that waste – other than pollution – can be conceived and used as the virgin material in the production process. Namely, the life-cycling thinking incorporated in the CE concept stresses the need to take into account the environmental impacts of the entire material lifecycle in an integrated way.Footnote 47

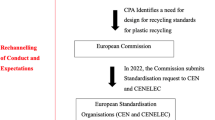

The fact that the CE put the spotlight on the life-cycle perspective constitutes a clear sign towards the building of interlinkages among the legally binding product standards, resource and waste law and policy, and the legislation on chemicals, given that the decisions made in the period when a product is conceptualized and manufactured by industry (design stage) are extremely important for all the stages of its lifetime. In this vein, the CE Package of 2015 recognized public procurement as a key driver in the transition towards the circular economy, and it sets out several actions which the European Commission will take to facilitate the integration of circular economy principles in GPP.Footnote 48 These include emphasizing circular economy aspects in new or updated sets of EU GPP criteria, supporting a higher uptake of GPP among European public bodies, and leading by example in its own procurement and in EU funding.Footnote 49

Based on this policy, the concept of “circular public procurement” has emerged. According to the definition given by the European Commission,Footnote 50 it refers to an approach to greening procurement by recognizing the role that public authorities can play in supporting the transition towards a circular economy. In other words, circular procurement can be defined as the process by which public authorities purchase works, goods or services that seek to contribute to close energy and material loops with supply chains, whilst minimizing, and in the best case avoiding negative environmental impacts and waste creation across their whole life-cycle.

Given that the transition towards a circular economy at EU level remains one of the first priorities under the EU Green Deal, a new Circular Economy Action Plan was published in March 2020 stressing the need to tackle the environmental and climate impact of our products and economic activities.Footnote 51 The new CE Action Plan puts the spotlight on the creation of an overarching sustainable product policy framework as a way to ensure that products which are either short-lived, toxic, unrepairable, unrecyclable or simply untraceable, are phased out from the EU market. Hence, the focus is on the sectors that use most resources and where the potential for circularity is high such as: electronics and ICT, batteries and vehicles, packaging, plastics, textiles, construction and buildings, food, water and nutrients. Additionally, there is a proposal to develop waste prevention targets, expand the use of Extended Producer Responsibility tools and restrict the waste exports outside the EU. In this context, the crucial role of public procurement in treating waste as a resource with energy and materials embedded in products, which must be kept in the economic process for as long as possible and at the higher level of quality,Footnote 52 was reiterated in the new CE Action Plan.

4.5 Climate change and decarbonization of the economy

The evolution of climate change and low carbon agendasFootnote 53 over the last decades have gradually been raising the expectation of public procurement that it should act as a practical and policy instrument for emissions’ reductions. Namely, in December 2015 the Paris Agreement was adopted with the long-term goal of keeping the global temperature increase by the end of the century to well below \(2~^{\circ}\mbox{C}\) (and pursue efforts towards \(1.5~^{\circ}\mbox{C}\)) compared to pre-industrial levels.Footnote 54 More specifically, the agreement stressed the urgent need for signatory parties to “undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with the best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century”.Footnote 55 The main instrument of national voluntary pledges is the National Determined Contributions (NDC) which is put forward by each signatory party and reviewed every five years.

The EU (and its MS) has traditionally been among the leaders at international level for setting ambitious policies to tackle climate change. The EU is signatory of all main international climate agreements and has consistently and actively contributed to the processes relating to the negotiation, adoption and entering into force of climate instruments.Footnote 56 In this vein, the EU has adopted a number of climate policy and legal instruments since 1992.Footnote 57 Focusing on the most recent developments, in 2018 the EU adopted its new and very ambitious 2030 framework for Climate and Energy relating to the implementation of the Paris Agreement. The agreed headline targets provide for at least 40% cuts in GHG emissions (from 1990 levels), 32% share for renewable energy and 32.5% improvement in energy efficiency. In this context, the “Transition to a Low-carbon Economy” Package and the “Clean Energy for all” Package were adopted.

The relevance of the public procurement as regards the achievement of the climate-related commitments has been explicitly recognized in the new Public Procurement Directive, since the integration of energy efficiency considerations in procurement and public administrations across EU MS could save up to 20% of their energy use by 2020, with corresponding carbon reductions.Footnote 58 At global level, Sustainable Public Procurement (SPP) has been introduced by at least 56 national governments and many more local governments, who have long understood how public procurement can improve sustainability, including through lowering greenhouse gas emissions.Footnote 59

In the wake of the proposal for an EU Climate Law under the EU Green DealFootnote 60 and the urgency of climate challenges, the rationale for climate-oriented public purchasing in the EU is more valid than ever. Hence, GPP offers authorities the option to make purchase decisions based on implicit carbon prices that are higher than the general carbon price, as well as taking into account more environmental impacts than solely carbon emissions.Footnote 61 This implies that when buying green products and services, authorities can substantially reduce their own environmental impactFootnote 62 by using their discretion towards the actual integration of more stringent climate consideration in their public procurement decisions. Given that GPP has been (more actively) on the EU political agenda for more than a decade now, MS should start designing and implementing more ambitious low-carbon strategies where public procurement can play a more prominent role in ensuring compliance with the relevant environmental objectives.

5 Exploring the ways to give effect to the GPP requirements

5.1 Unpacking the discrepancies between discretion and effectiveness

The official introduction of environmental and social considerations in the Public Procurement Directive marked a new era in the promotion of social and environmental objectives – consolidated in the so-called EU “secondary” and “horizontal” policies – through the public procurement rules. Under the general term “Strategic Procurement”,Footnote 63 which covers green, social and sustainable public procurement, the European Commission stressed that “it should play a bigger role for central and local governments to respond to societal, environmental and economic objectives, such as the circular economy”.Footnote 64 In the same vein, Recital 123 of the Directive highlights that “in order to fully exploit the potential of public procurement to achieve the objectives of the Europe 2020 Strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, environmental, social and innovation procurement will also have to play its part”.

Allowing for the introduction of social and environmental requirements within the EU Public Procurement regime, the Public Procurement Directive constitutes an important driver towards greening public purchasing so far. However, the initial ambitions regarding the change in the nature of public procurement from an instrument for ensuring the integrity of the internal market in public contracts into a mechanism for achieving compliance with EU policy objectives were lowered, given that the majority of the relevant provisions adopted in the final text were of a voluntary nature. Consequently, MS and contracting authorities are left with the discretionary power to decide whether and/or how to apply the available but facultative provisions.

Notwithstanding that the Directive created a fertile ground so that environmental (and social) considerations are facilitated under its regime, the decision to opt for the voluntary nature of these provisions subjected to MS’ (and contracting authorities’) exercise of their discretion, opened Pandora’s box. Hence, in order to ensure that this discretion allocated to MS (and contracting authorities) will not lead to arbitrary use and, therefore, jeopardize the effective application of the Directive, clear boundaries need to be set. As Andhov pointed out, there is a double approach to the limitations relating to the contracting authorities’ discretion in pursuing environmental goals.Footnote 65 Namely, the first set of limitations aims to safeguard the procurement’s functional objectives and covers the requirement on a “link to the subject matter” of the contractFootnote 66 as well as the compliance with the general procurement principle (principles of equality, non-discrimination, transparency and proportionality) and the “competition-based constraints”Footnote 67 enshrined in Article 18(1) of the Public Procurement Directive.

According to the second approach, certain limitations refer to the MS’ (and, by extension, a contracting authority’s) freedom to enable or ignore GPP.Footnote 68 This second set of limitations derives from the small number of GPP provisions with mandatory character (Articles: 18(2), 69 and 71 of the Public Procurement Directive) and its scope depends on the normative content of these provisions. Thus, contrary to the clear demarcation of the first set of limitations, the delimitation of the second body of limitations is determined mainly by the content and the (binding?) effect of Article 18(2).

More specifically, Article 18(2), which falls under the so-called “principles of public procurement” section of the Public Procurement Directive, stipulates that “MS shall take appropriate measures to ensure that in the performance of public contracts economic operators comply with applicable obligations in the fields of environmental, social and labour law[…]”. Despite the fact that this provision is enshrined in the part referring to the “principles of procurement”, the majority of the theory reasonably questions such legal classification,Footnote 69 even if it is acknowledged that the overarching principle underpinning this provision is the principle of Sustainable Development.Footnote 70 However, most of the complexity relating to the enforcement of Article 18(2) is not about its legal classification, but its legal consequences.

The wording of this provision raises more questions than it answers. First of all, it is not clear whether it lays down a general obligation with specific legal consequences in case of its violation, or a general duty simply inviting MS to include environmental and social consideration in public procurement procedure. It is true that the use of the verb “shall” advocates the “obligation” option despite the ambiguity surrounding its legal content. That being said, if a Member State has not transposed Article 18(2) and the contracting authority has failed at some point in the public procurement process to take measures to check the compliance mentioned in Article 18(2), what would the legal consequences be?Footnote 71 In the same vein, provided a Member State fully transposes Article 18(2), but the national contracting authorities decide not to take any measures to ensure compliance according to this provision, how will the use of their discretionary power be reviewed?

Moreover, the concept of “appropriate measures” expected to be taken by the MS does not shed light on the concrete tasks to be taken over so that this provision is given fully effect. Finally, as regards the addressees of this obligation, Article 18(2) explicitly made reference only to “MS” leaving aside the contracting authorities. However, assuming that only MS are subject to this rule would seem to run counter to Recital 37 which stresses that “it is of particular importance that MS and contracting authorities take relevant measures to ensure compliance with obligations in the fields of environmental, social and labour law”. Thus, it is considered that both MS and contracting authorities are bound by this provision.Footnote 72

On the basis of the above, it is evident that although the Public Procurement Directive officially recognized the crucial role in greening the public purchasing process and aspired to set an enforceable policy tool for achieving environmental objectives, the ambiguous formulation and the decision to subject its activation to the discretionary power of the contracting authorities led to the creation of a potentially dynamic – but full of legal uncertainties – toolbox. Due to these legal uncertainties and despite the determined efforts on behalf of the Commission since the year 2003, the actual uptake of GPP remains limited and not linear across the EU.Footnote 73 This fragmented uptake together with the weak enforcement of the public procurement rules allowing environmental considerations, demonstrate that the current framework failed to serve as a lever to promote the essential organizational and behavioral changes at national level. Hence, the GPP state of play reveals that it still remains an underdeveloped (and unexplored) field in practice.

Integrating “green” criteria into the different stages of procurement procedure at national level is not an automatic consequence followed by the adoption of the relevant piece(s) of legislation but requires a long-standing commitment to strategic decisions concerning the training, counselling and monitoring of public procurers as well as the administrative structure of GPP itself. The shift from GPP-unskilled public officials who are not in a position to understand the GPP regulations and evaluate their benefits to qualified and committed public officials who are able to determine the exact green criteria that may translate into economic surplus under the life-cycle costing method of awarding a tender is a complex process that requires time and determined efforts.Footnote 74 Financial constraints, obsolete administrative structures as well as lack of human resources especially in small sized authorities need also to be brought into this equation.Footnote 75

Having this background regarding GPP in mind and taking into consideration the repetitive Commission’s policy statements for the promotion of green purchasing and the use of GPP as a mechanism to enforce compliance with environmental objectives, the question that comes up is how to move from the stage of urges and invitations to the stage of fulfilling an obligation.Footnote 76 In other words, how can the binding environmental policy objectives, which explicitly deepen the ties between public procurement and environmental policy, be operationalized/enforced under the current – voluntary and abounding with legal uncertainties due to the discretion allocated to contracting authorities – public procurement rules?

5.2 How to move from invitation to obligation?

As portrayed in the previous part, the legal complexity and the voluntary nature of public procurement rules have failed to effectively contribute to the efforts to increase awareness and knowledge as well support the practical experience of public procurers in the field of GPP. Hence, the policy and legislative ambition to achieve regulatory compliance with environmental objectives by greening public purchasing has not successfully effectuated so far. In this context, it is evident that neither the MS nor the contacting authorities have been asked – in a legally binding and scientifically sound fashion – to find ways to make the existing GPP regime deliver its full potential.

Improving the integration of the green considerations in procurement procedures and, by extension, ensuring compliance with the environmental policy objectives, would entail more profound organizational and behavior changes leading to the development of new skills and structures which will actually increase the ability, knowledge and motivation to enforce GPP provisions. However, the voluntary and legally volatile character of the existing GPP framework, which codifies existing behaviors rather than imposes far-reaching adjustment requirements, does not confront contracting authorities with actual incentives to procure green.Footnote 77 In other words, none of the various legal instruments offered by the provisions of the Public Procurement Directive seems to be conducive to effectively promoting a shift from the business-as-usual towards understanding and accounting for environmental impacts on public purchasing practices.Footnote 78

Seeking to fix these asymmetries between the policy imperatives to take environmental requirements into account and the constraints of the existing public procurement legislative toolkit in order to accommodate them, the way forward passes through the discussion about introducing mandatory elements into the GPP setting. The experience gained so far by the implementation of mandatory sectoral GPP rules is limited and cannot necessarily give decisive guidance for balancing the potential benefits and the side-effects from the extension of GPP mandatory provisions. However, as bluntly noted by Melon, the positive impact of mandatory legislation – despite its economic and administrative costs – seems to be two-fold: it incentivizes further market developments in providing environmentally-friendly solutions, and provides a strong and efficient incentive for public procurers to engage in GPP.Footnote 79

With regard to the adoption of mandatory elements in particular, the starting point should be Article 18(2). As highlighted in the previous part, the ambiguity relating to the binding force of this provision undermines the effectiveness of all GPP provisions under the Public Procurement Directive. Thus, it is of paramount importance to determine the unclear terms of “shall” and “appropriate measures” in such a way that sound normative content will be instilled into this provision. Consequently, a clear and unequivocal general provision which obliges (and not simply allows or encourages) the contracting authorities to enforce GPP requirements will unlock the full potential of public procurement as a lever for ensuring compliance with environmental policy objectives.

In this vein, such a general mandatory provision will impart normative clarity to the other relevant Articles of the Public Procurement Directive where the limitations to MS’ and contracting authorities’ discretionary power weaken their binding content. For example, according to the formulation of Article 57(4), “contracting authorities may exclude or may be required by MS to exclude from participation in a procurement procedure any economic operator, [in case of] violation of applicable obligations referred to in Article 18(2)”. The same applies to Article 70 relating to contract performance conditions. An adjustment towards a mandatory framework would bring these “non-mandatory” provisions in line with the “mandatory” formulation of Article 69 which explicitly requires contracting authorities to reject the tender, in case (among others) the non-compliance with the obligation deriving from Article 18(2) leads to an abnormally low tender.

Moreover, introducing specific mandatory requirements will be the necessary complement to the general obligation. Namely, the easiest (first) step would be to make the EU GPP criteria mandatory. As indicated on the European Commission’s webpage, these criteria have been developed to facilitate the inclusion of green requirements in the procurement documents aiming to reach good balance between environmental performance, cost considerations, market availability and ease of verification. The European Commission is constantly developing this fieldFootnote 80 and, in case these criteria become mandatory, it would be in a position to provide guidance and support for their effective implementation.

One possible (and maybe the easiest) form of giving effect to the aforementioned introduction of mandatory elements would be the introduction of national GPP minimum targets.Footnote 81 More specifically, the EU legislation will require from MS a certain percentage of public procurement to be green, with a phase-in provision requiring 100% at a certain date.Footnote 82 Such a provision will force contracting authorities to systematically invest in raising the awareness as well as improving the knowledge and the ability of public officers to green public spending, whereas it will contribute to narrowing the GPP uptake gap among MS. It goes without saying that the adoption of this provision should be accompanied with EU-harmonized monitoring and tracking mechanisms as well as effective guidance and information systems.

A very interesting reform proposal included in the recent joint publication of the SMART Project Report refers to the removing of the “link to the subject-matter” of the contract and its replacement by the concept of “life cycle”.Footnote 83 As already presented in this paper, the requirement of “link to the subject matter” of the contract is included in almost all procurement stages and constitutes one of the limitations to contracting authorities’ discretionary power in inserting environmental considerations into the public procurement setting. According to this proposal, the departure from the “link to the subject matter” of the contract requirement is imposed by the need to have recourse to a less ambiguous and more “fit for purpose” concept.

To that end, the notion of life cycle, which is expressly defined in Article 2(20) as “all consecutive and/or interlinked stages, including research and development to be carried out, production, trading and its conditions, transport, use and maintenance, throughout the existence of the product or the works or the provision of the service, from raw material acquisition or generation of resources to disposal, clearance and end of service or utilisation”, seems to offer a more firm legal basis in order to strengthen the GPP. Consequently, according to that reform proposal, the “link to the subject matter” reference in Articles 42, 43, 45, 67, 68 and 70 of the Public Procurement Directive should be replaced by a “life cycle” reference, as follows “the product, service or works (or and) its life cycle”.Footnote 84

While always bearing in mind that this is an exercise for joining the dots between public procurement and environmental policy, an additional argument in favor of this proposal could be the fact that the “Life Cycle Thinking” is not an unknown concept within EU environmental law and policy. This concept has recently attracted much attention due to the shift of environmental policy towards the environmental impacts during the entire product life cycle (“from cradle to grave”). Despite its still ambiguous and open to interpretation content, life cycle concept is reflected in the EU Integrated Product Policy and the Eco-design Detective.Footnote 85 However, the most significant boost to this concept was given in the field of waste law and policyFootnote 86 and mainly in the wake of the adoption of the circular economy package, already presented above.Footnote 87

As regards the life cycle costing (LCC) methodology enshrined in Article 68 and mentioned in Article 67(2) of the Public Procurement Directive, it constitutes an instrument to evaluate all the costs over the life cycle of works, supplies or services including both internal costs (related to acquisition, use, maintenance and end of life) and “cost imputed to environmental externalities (cost of mitigating/reducing environmental impacts) linked to the product, service or works during its life cycle, provided their monetary value can be determined and verified”.Footnote 88 Its main purpose is to evaluate the various options (tenders) for achieving the contracting authority’s objectives (including environmental and societal goals), where those alternatives differ not only in their initial costs but also in their subsequent operational costs.Footnote 89

Putting an LCC methodology into practice is a rather complicated task, as it presupposes the development of a methodology suitable to the specific characteristics of the supplies, services or works the contracting authority intends to buy. This task is left (again) to the MS (with the exception of the requirements under the Clean Vehicles Directive) leading to the great challenges in systematically giving effect to LCC still faced by public institutions.Footnote 90 In this context, maybe it is time to adopt an EU-wide common method for the calculation of LCC for specific categories of supplies or services,Footnote 91 which will automatically become the mandatory point of reference among MS according to Article 68(3). Such a step should, of course, be coupled with guidelines and other material providing detailed explanations and increasing understanding of LCC at national level.Footnote 92

Furthermore, mandatory elements may be inserted in further developing an eco-labelling scheme and its use. Finally, according to an older (before the 2014 reform) but still relevant proposal, the obligatory abandonment of the lowest-price criterion for the award of the contract and the exclusive use of the most economically advantageous tender was suggested. Allowing contracting authorities to opt for the lowest-price option – with no safeguards to ensure that environmental protection requirements are fulfilled – may lead to accepting the fact that GPP remains on the sidelines.Footnote 93

6 Concluding remarks

The present paper has attempted to strike some sort of balance between the traditional role of public procurement (transparency, best value for money, competition concerns and the creation of a strong internal market) and the new role allocated more directly to the public procurement regime since the 2014 reform as a policy tool for promoting green, innovative and inclusive growth. Taking into consideration their predominant role in mass consumption, public authorities have, therefore, a significant influence on the way goods, services and works are chosen.Footnote 94 On that basis, they could use their power to structure this selection process in a way that would reduce the environmental impact and promote main environmental policy goals. This approach led to the emergence of the GPP, which constitutes the mechanism to tie environmental requirements to public spending.

Even though the current EU Public Procurement regime opened the door for a potential transition towards a more operational integration of environmental considerations into public purchasing, the existing legal uncertainties undermine EU legislator’s good intentions. Namely, the voluntary GPP uptake coupled with the wide scope of contracting authorities’ discretion in pursuing environmental goals hampers any dynamic features aiming to increase implementation and enforcement. In addition to this, due to the legally ambiguous formulation of Article 18(2), the obligation of MS and contracting authorities to take appropriate measures to ensure that the economic operators comply with the enforceable requirements in the fields of environmental, social and labor law may turn into an idle declaratory policy statement.

In this context, the EU Green Deal, which constitutes the new EU policy roadmap for the upcoming years, stressed once again the predominant role of the public procurement in achieving the ambitious EU environmental policy goals. Being an overarching policy framework, which encompasses other policy areas such Sustainable Development, Circular Economy and Climate change, it calls for determined efforts for giving effect to the GPP in order to bring the realization of a “smart, sustainable and inclusive growth” closer. Addressing this challenge and examining ways to empower the role of public procurement as a compliance mechanism for supporting the EU environmental policy commitments, the introduction of mandatory elements will bring more legal certainty as regards the interpretation and implementation of the relevant provisions by the contracting authorities increasing their enforceability and, by extension, the actual GPP uptake.

Notes

European Commission, Bying Green! – A Handbook on green public procurement, 3rd edition, 2016, pp. 4–5.

H. Schebesta, [26], pp. 130–131.

K.V. Thai, [33], p. 2.

Recital 3 of Directives 2014/23/EU, 2014/24/EU and 2014/25/EU.

European Commission, Europe 2020 – A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, pp. 14–17.

European Commission, [12], pp. 219–223.

European Commission, Communication, Public procurement for a better environment, 2008.

Copyright and graphic paper, computer and monitors, transport, electricity, textiles, cleaning products and services, Office Building, Furniture, Food and Catering Services, Gardening products and services, wall panels, water-based heaters, waste water infrastructure, flushing toilets and urinals, imaging equipment, roads, combined heat and power, street lighting and traffic signals, Indoor lighting, sanitary tapware, EEE Health care sector.

H. Schebesta, [27], p. 319.

L. Mélon, [23], p. 5.

Centre for European Policy Studies and College of Europe, The Uptake of Green Public Procurement in the EU27. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/CEPS-CoE-GPP%20MAIN%20REPORT.pdf.

C-513/99 Concordia Bus Finland, C-448/01 EVN AG & Wienstrom and C-368/10 Dutch Coffee or Max Havelaar.

European Commission, Public Procurement Reform Factsheet No. 7: Green Public Procurement, 2014.

SIGMA, [28], p. 5.

S. Weatherill, [37], pp. 41–42.

E. van den Abeele, [36], p. 12.

B. Martinez-Romera and R. Caranta, [22], p. 291.

SIGMA, [28], p. 9.

D.C. Dragos and B. Neamtu, [11], pp. 301–302.

C. Burns, P. Eckersley and P. Tobin, [5], p. 4.

L. Krämer, [17], pp. 33–38.

European Commission, A Blueprint to Safeguard Europe’s Water Resources COM(2012)673. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012DC0673&from=EN.

M. Lee, [19], pp. 67–68.

P. Thieffry, [34], p. 70.

B. Sjåfjell, [30], p. 58.

J.H. Jans and H.H.B. Vedder, [16], pp. 22–23.

G. van Calster and L. Reins, [35], pp. 22–23.

L. Krämer, [18], p. 84 explaining that the other integration clauses would only require to “deploy best efforts” or “to consider” a certain matter.

C-161/04, Austria v Parliament and Council, Order of the President of the First Chamber of the Court of 6 September 2006, para. 59.

C-428/07, Horvath, Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 16 July 2009, para. 29.

C-440-05, Commission v Council, Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 23 October 2007, para. 60.

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Sustainable Europe Investment Plan – European Green Deal Investment Plan, Brussels, 14.1.2020, COM(2020) 21 final, p. 8.

Ibid., p. 12.

B. Martinez Romera and R. Caranta, [22], pp. 281–282.

E. Fisher, [14], p. 2.

I. Litardi, G. Fiorani, and D. Alimonti, [20], 2020, p. 177.

I.E. Nikolaou, and C. Loizou, [24], p. 50.

M. Lee, [19], p. 130.

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – Closing the loop – An EU action plan for the Circular Economy, Brussels, 2.12.2015, COM(2015) 614 final.

R. Hughes, [15], pp. 14–15.

European Parliament, [13], pp. 14–19.

European Commission, Public Procurement for a Circular Economy – Good practice and guidance, 2017, p. 5. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/Public_procurement_circular_economy_brochure.pdf.

Ibid., p. 5.

ZeroWaste, [38], p. 5.

In 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted aiming at the “stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system” (Article. 2). In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol set binding quantified emission limitation or reduction objectives for developed countries, including the EU MS, without, however, leading to their practical implementation. See F. Sandico, The UNFCCC: legal scholarship in four key areas, in D.A Faber and M. Peeters, Climate Change Law, Edward Edgar Publishing, 2016, pp. 217–226.

UNFCCC, Paris Agreement (Paris, 12 December 2015), Article 2.1.

Paris Agreement, Article 4.1.

B. Martinez Romera and R. Caranta, EU Public Procurement Law Purchasing beyond price in the age of Climate Change, EPPPL, 3/2017, p. 283.

S. Bogojević, [3], pp. 671–688.

F. Correia, M. Howard, B. Hawkins, A. Pye, R. Lamming, [7], p. 58.

R. Baron (OECD), The Role of Public Procurement in Low-Carbon Innovation, Background Paper for the 33rd Round Table on Sustainable Development, 12–13 April 2016, OECD Headquarters, Paris, available at: https://www.oecd.org/sdroundtable/papersandpublications/The%20Role%20of%20Public%20Procurement%20in%20Low-carbon%20Innovation.pdf.

B. Martinez Romera and R. Caranta, EU Public Procurement Law Purchasing beyond price in the age of Climate Change, EPPPL, 3/2017, p. 282.

O. Chiappinelli and V. Zipperer, [6], p. 524.

European Commission, [12], p. 220.

European Commission, Making Public Procurement work in and for Europe, COM(2017), 572 final, p. 8.

M. Andhov, [1], p. 127.

M. Martens and S. de Margerie, [21], pp. 8–18.

A. Sanchez-Graells, [25], pp. 79–98.

M. Andhov, [1], pp. 127–128.

Ibid., p. 132.

S. Bogojevic, [4], pp. 178–179.

M. Andhov, [1], p. 129.

S. Bogojevic, [4], p. 172.

L. Mélon, [23], p. 3.

I. Litardi, G. Fiorani, and D. Alimonti, [20], pp. 177–179.

F. Testa, P. Grappio, N.M. Gusmerotti, F. Iraldo, M. Frey, [32], pp. 199–200.

F. de Leonardis, [10], pp. 110–113.

J. Tallberg, [31], p. 612.

L. Mélon, [23], p. 15.

Ibid., p. 15.

In June and July 2020 new GPP were adopted relating for imaging equipment, consumables and print services and data centres, server rooms and cloud services. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/eu_gpp_criteria_en.htm.

M. Andhov and R. Caranta (eds.), [2], pp. 43–44.

L. Melon, [23], p. 16.

M. Andhov and R. Caranta (eds.), [2], pp. 37–38.

Ibid., p. 39.

C. Dalhammar, [9], pp. 109–114.

According to the second paragraph of Article 4 of the Waste Framework Directive establishing the waste hierarchy principle, “[…departing from the hierarchy where this is justified by life-cycle thinking on the overall impacts of the generation and management of waste]”.

Special emphasis was given to this concept with the European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:2df5d1d2-fac7-11e7-b8f5-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

SIGMA, [29], p. 6.

SIGMA, [29], p. 1.

D. Dragos and B. Neamtu, [11], pp. 22–24.

J.J. Czarnezki, [8], pp. 230–231.

SIGMA, [29], p. 10.

ClientEarth, Procuring best value for money – Why eliminating the “lowest price’ approach to awarding public contracts would serve both sustainability objectives and efficient public spending, 2012, pp. 3–4. Available at: https://www.documents.clientearth.org/wp-content/uploads/library/2012-05-01-procuring-best-value-for-money-ce-en.pdf.

European Commission, Environment – Buying Green Handbook, 2013, p. 4. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/Buying-Green-Handbook-3rd-Edition.pdf.

References

Andhov, M.: Contracting authorities and strategic goals of public procurement – a relationship defined by discretion? In: Bogojevic, S., Groussot, X., Hettne, J. (eds.) Discretion in EU Public Procurement, pp. 117–137. Hart Publishing, Chicago (2019)

Andhov, M., Caranta, R. (eds.): Sustainability through public procurement: the way forward – reform proposals. SMART Project Report, (March 2020). Available at: https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/Sustainability_through_public_procurement_the_way_forward_Reform_Proposals.pdf

Bogojević, S.: Climate change law and policy in the European Union. In: Gray, K.R., Tarasofsky, R., Carlarne, C. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of International Climate Change Law, pp. 671–688. Oxford University Press, London (2016)

Bogojevic, S.: Mapping public procurement and environmental law intersections in discretionary space. In: Bogojevic, S., Groussot, X., Hettne, J. (eds.) Discretion in EU Public Procurement, pp. 161–185. Hart Publishing, Chicago (2019)

Burns, C., Eckersley, P., Tobin, P.: EU environmental policy in times of crisis. J. Eur. Public Policy 27(1), 1–19 (2019)

Chiappinelli, O., Zipperer, V.: Using public procurement as a decarbonization policy: a look at Germany. DIW Econ. Bull. 49, 523–533 (2017)

Correia, F., Howard, M., Hawkins, B., Pye, A., Lamming, R.: Low carbon procurement: an emerging agenda. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 19, 58–64 (2013)

Czarnezki, J.J.: EU and US discretion in Public Procurement Law: the role of eco-labels and life-cycle costing. In: Bogojevic, S., Groussot, X., Hettne, J. (eds.) Discretion in EU Public Procurement, pp. 211–247. Hart Publishing, Chicago (2019)

Dalhammar, C.: The Application of “life cycle thinking” in European environmental law: theory and practice. J. Environ. Plan. Law 12, 97–127 (2015)

de Leonardis, F.: Green public procurement: from recommendation to obligation. Int. J. Public Adm. 34, 110–113 (2011)

Dragos, D., Neamtu, B.: Sustainable public procurement: lifecycle in the new EU directive proposal. Eur. Procure. Public Priv. Partnersh. Law 1, 22–24 (2013)

European Commission: Strategic public procurement: facilitating green, inclusive and innovative growth. Eur. Procure. Public Priv. Partnersh. Law 3, 219–223 (2017)

European Parliament: Green public procurement and the EU action plan for the circular economy, study for the ENVI Committee (2017). Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/602065/IPOL_STU(2017)602065_EN.pdf

Fisher, E.: The power of purchase: addressing sustainability through public procurement. Eur. Procure. Public Priv. Partnersh. Law 1, 1–7 (2013)

Hughes, R.: The EU circular economy package – life cycle thinking to life cycle law? Proc. CIRP 61, 10–16 (2017)

Jans, J.H., Vedder, H.H.B.: European Environmental Law – After Lisbon, 4th edn. Europa Law Publishing, Groningen (2012)

Krämer, L.: The genesis of EC environmental principles. In: Macrory, R. (ed.) Principles of European Environmental Law. The Avosetta Series, vol. 4. European Law Publishing, Groningen (2004)

Krämer, L.: Giving a voice to the environment by challenging the practice of integrating environmental requirements into other EU policies. In: Kingston, S. (ed.) European Perspectives on Environmental Law and Governance, pp. 83–100. Taylor & Francis, London (2013)

Lee, M.: EU Environmental Law, Governance and Decision-Making, 2nd edn. Hart Publishing, Chicago (2014)

Litardi, I., Fiorani, G., Alimonti, D.: The state of the art of green public procurement in Europe: documental analysis of European practices. In: Brunelli, S., Di Carlo, E. (eds.) Accountability, Ethics and Sustainability of Organizations – New Theories, Strategies and Tools for Survival and Growth, pp. 175–192. Springer, Berlin (2020)

Martens, M., de Margerie, S.: The link to the subject-matter of the contract in green and social procurement. Eur. Procure. Public Priv. Partnersh. Law 3, 8–18 (2017)

Martinez-Romera, B., Caranta, R.: EU public procurement law: purchasing beyond price in the age of climate change. Eur. Procure. Public Priv. Partnersh. Law 3, 291 (2017)

Melon, L.: More than a nudge? Arguments and tools for mandating green public procurement in the EU. Sustainability 12, 1–24 (2020)

Nikolaou, I.E., Loizou, C.: The green public procurement in the midst of the economic crisis: is it a suitable policy tool? J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 12(1), 49–66 (2015)

Sanchez-Graells, A.: Some reflections on the “artificial narrowing of competition” as a check on the executive discretion in public procurement. In: Bogojevic, S., Groussot, X., Hettne, J. (eds.) Discretion in EU Public Procurement, pp. 79–98. Hart Publishing, Chicago (2019)

Schebesta, H.: EU green public procurement policy modernisation package, eco-labelling and framing measures. In: Schoenmakers, S., Devroe, W., Philipsen, N. (eds.) State Aid and Public Procurement in the European Union, pp. 130–131. Intersentia, Cambridge (2014)

Schebesta, H.: Revision of the EU green public procurement criteria for food procurement and catering services – certification schemes as the main determinant for public sustainable food purchases? Eur. J. Risk Regul. 9, 319 (2018)

SIGMA: Incorporating environmental considerations into public procurement, Brief 13 (2016). Available at: http://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Public-Procurement-Policy-Brief-13-200117.pdf

SIGMA: Life-cycle costing – public procurement, Brief 34 (September 2016). Available at: http://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Public-Procurement-Policy-Brief-34-200117.pdf

Sjåfjell, B.: The legal significance of Article 11 TFEU for EU institutions and member states. In: Sjåfjell, B., Wiesbrock, A. (eds.) The Greening of European Business Under EU Law: Taking Article 11 TFEU Seriously. Routledge, London (2015)

Tallberg, J.: Paths to compliance: enforcement, management, and the European Union. Int. Organ. 3(56), 609–643 (2002)

Testa, F., Grappio, P., Gusmerotti, N.M., Iraldo, F., Frey, M.: Examining green public procurement using content analysis: existing difficulties and useful recommendations. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 18, 197–219 (2016)

Thai, K.V. (ed.): Global Public Procurement Theories and Practices Springer, Berlin (2017)

Thieffry, P.: Handbook of European Environmental Law. Bruylant, Brussels (2018)

van Calster, G., Reins, L.: EU Environmental Law, Elgar European Law (2017)

van den Abeele, E.: Integrating social and environmental dimensions in public procurement: one small step for the internal market, one giant leap for the EU? Working Paper 2014.08, Brussels (2014). Available at: https://www.etui.org/publications/working-papers/integrating-social-and-environmental-dimensions-in-public-procurement-one-small-step-for-the-internal-market-one-giant-leap-for-the-eu

Weatherill, S.: EU law on public procurement: internal market law made better. In: Bogojevic, S., Groussot, X., Hettne, J. (eds.) Discretion in EU Public Procurement. Hart Publishing, Chicago (2019)

ZeroWaste Europe: Redesigning producer responsibility – a new EPR is needed for a circular economy (2015)

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pouikli, K. Towards mandatory Green Public Procurement (GPP) requirements under the EU Green Deal: reconsidering the role of public procurement as an environmental policy tool. ERA Forum 21, 699–721 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-020-00635-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-020-00635-5